Characteristics of the Fatty Acid Composition in Elderly Patients with Occupational Pathology from Organophosphate Exposure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Outcomes and Measures

2.3.1. Reagents and Standards

2.3.2. Blood Collection and Plasma Preparation

2.3.3. Determination of a Group of Biomarkers of Metabolic Syndrome and Fatigue in Blood Plasma

2.3.4. Selective Determination of Non-Esterified Fatty Acids and Esterified Fatty Acids in Blood Plasma

2.3.5. Biochemical Analysis

2.4. Statistical Data Processing

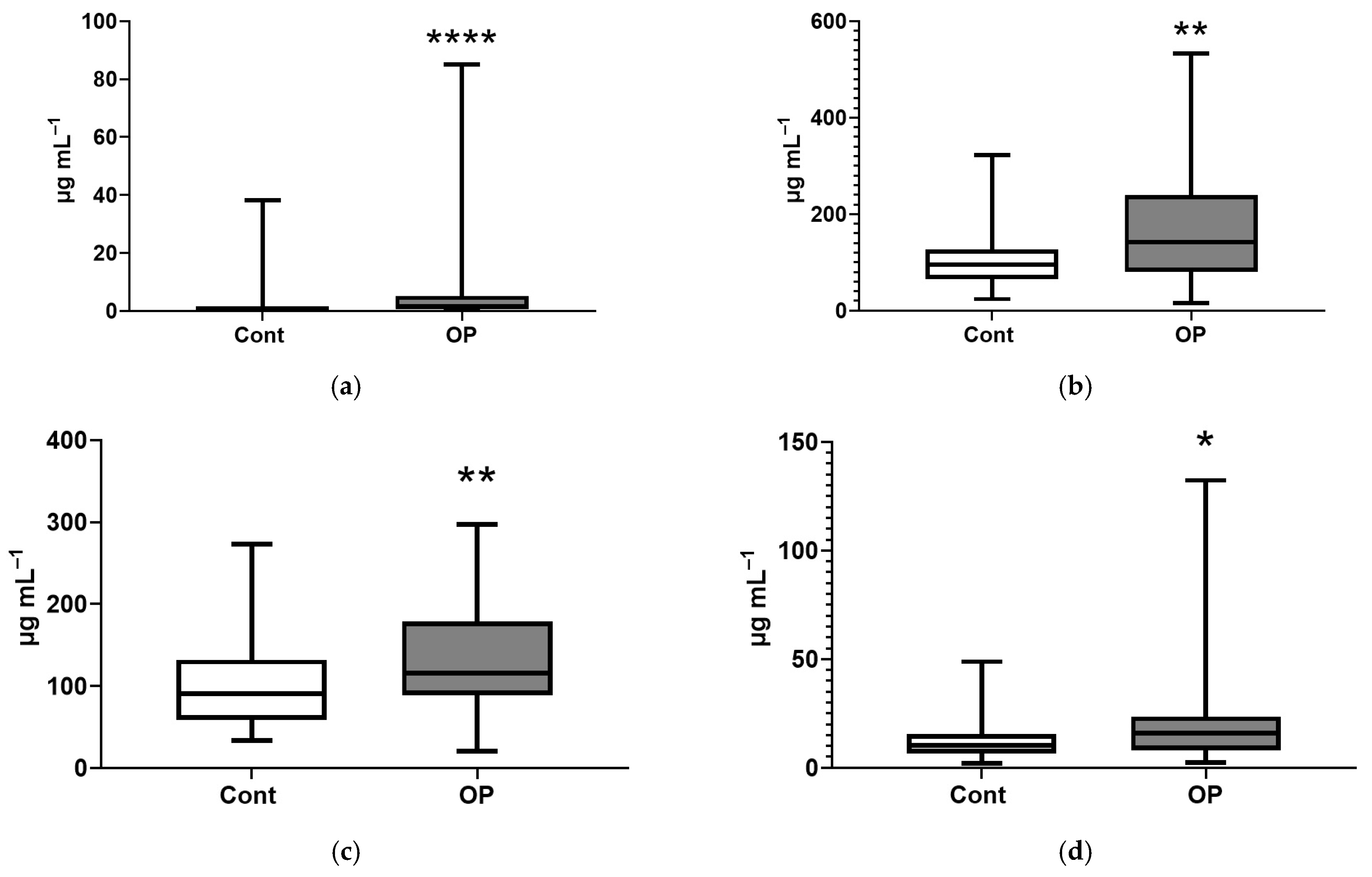

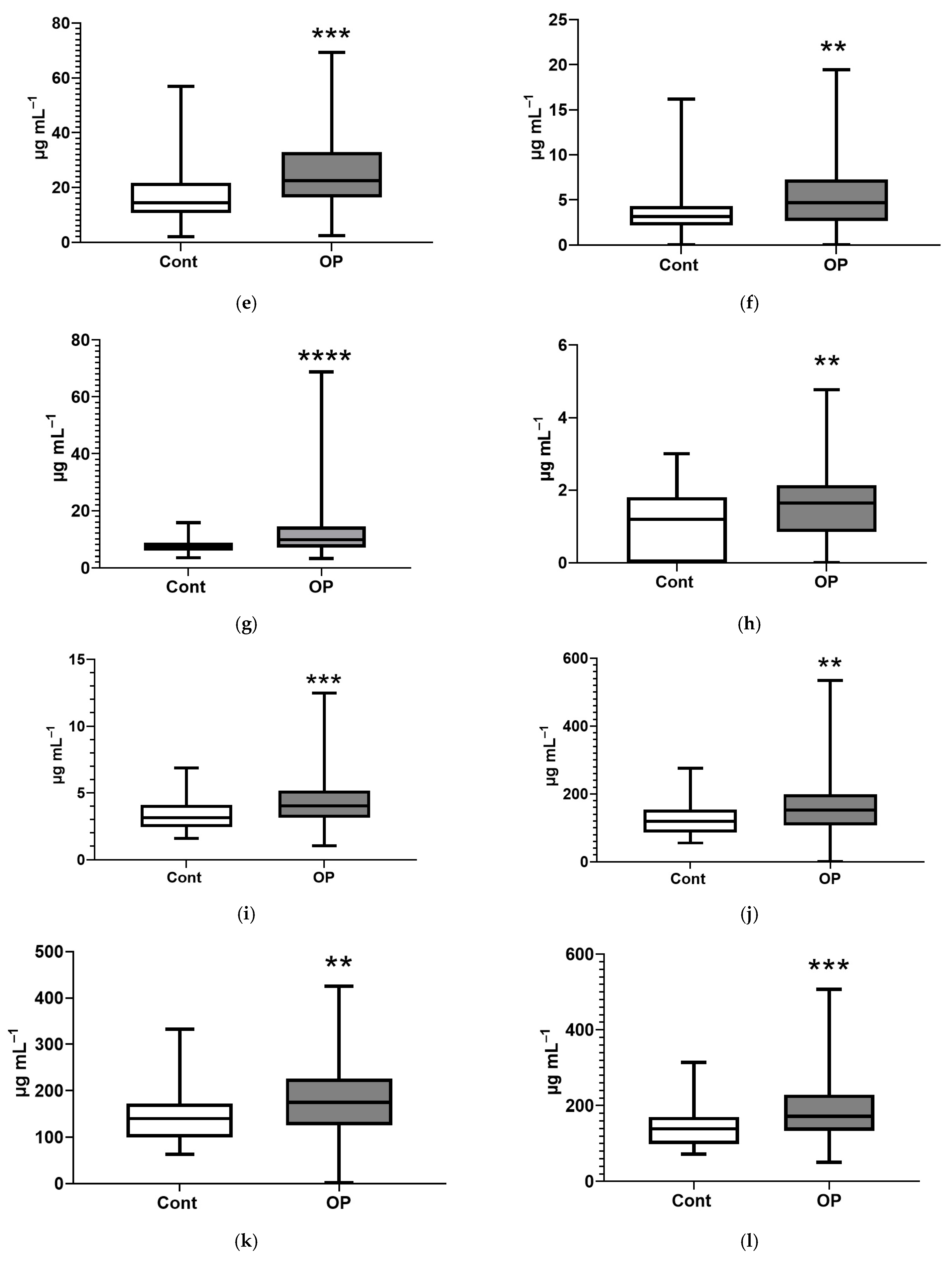

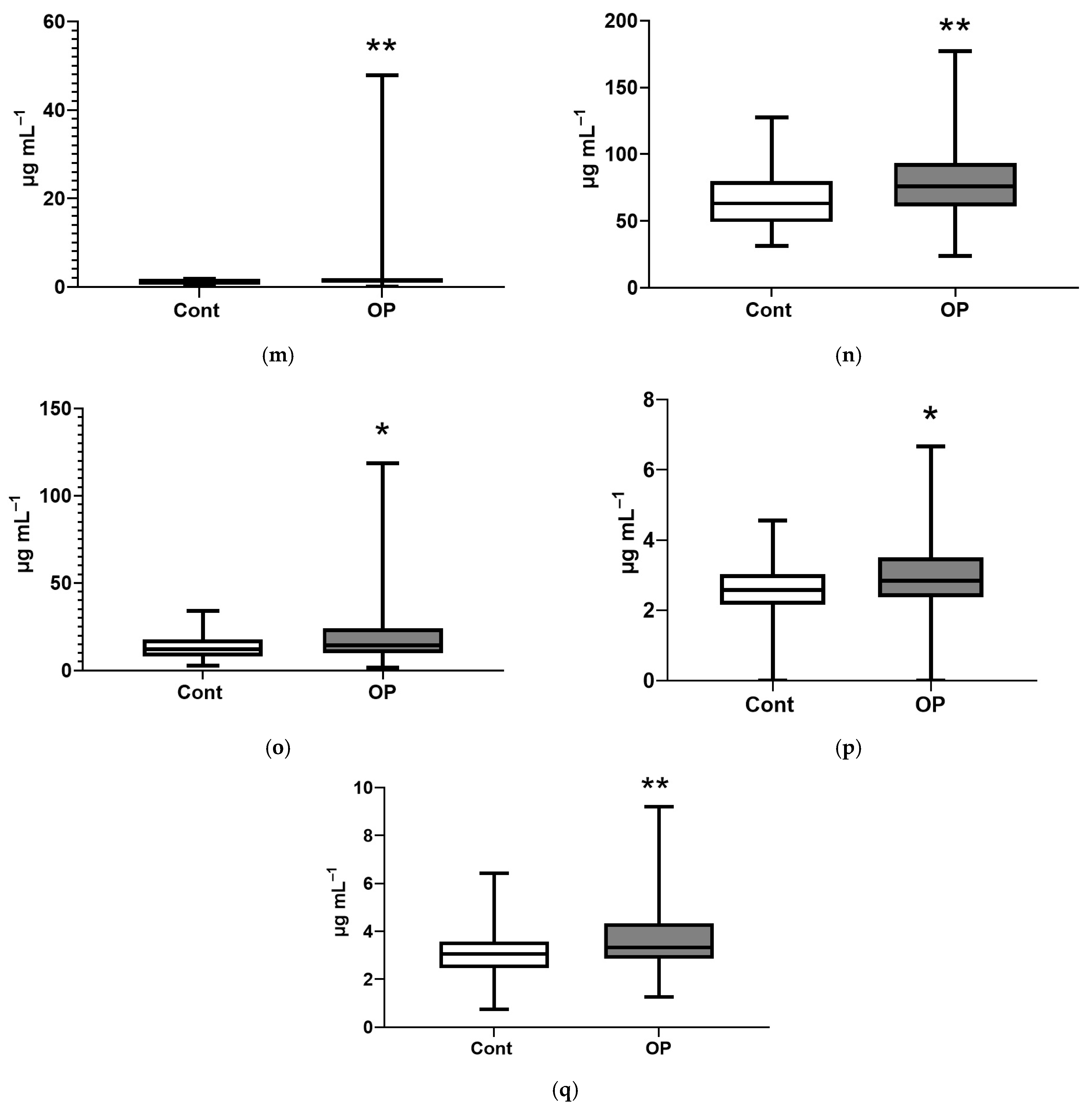

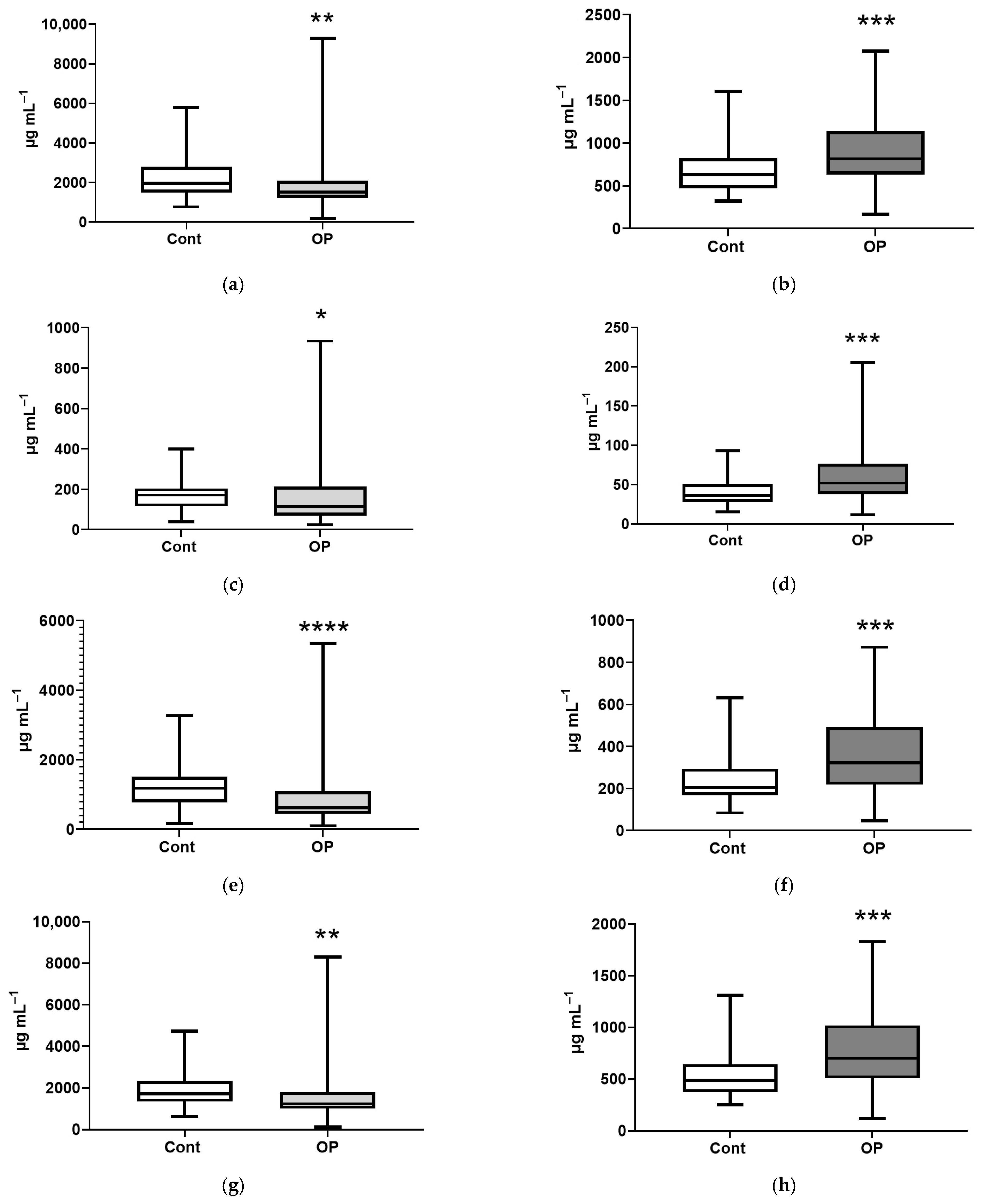

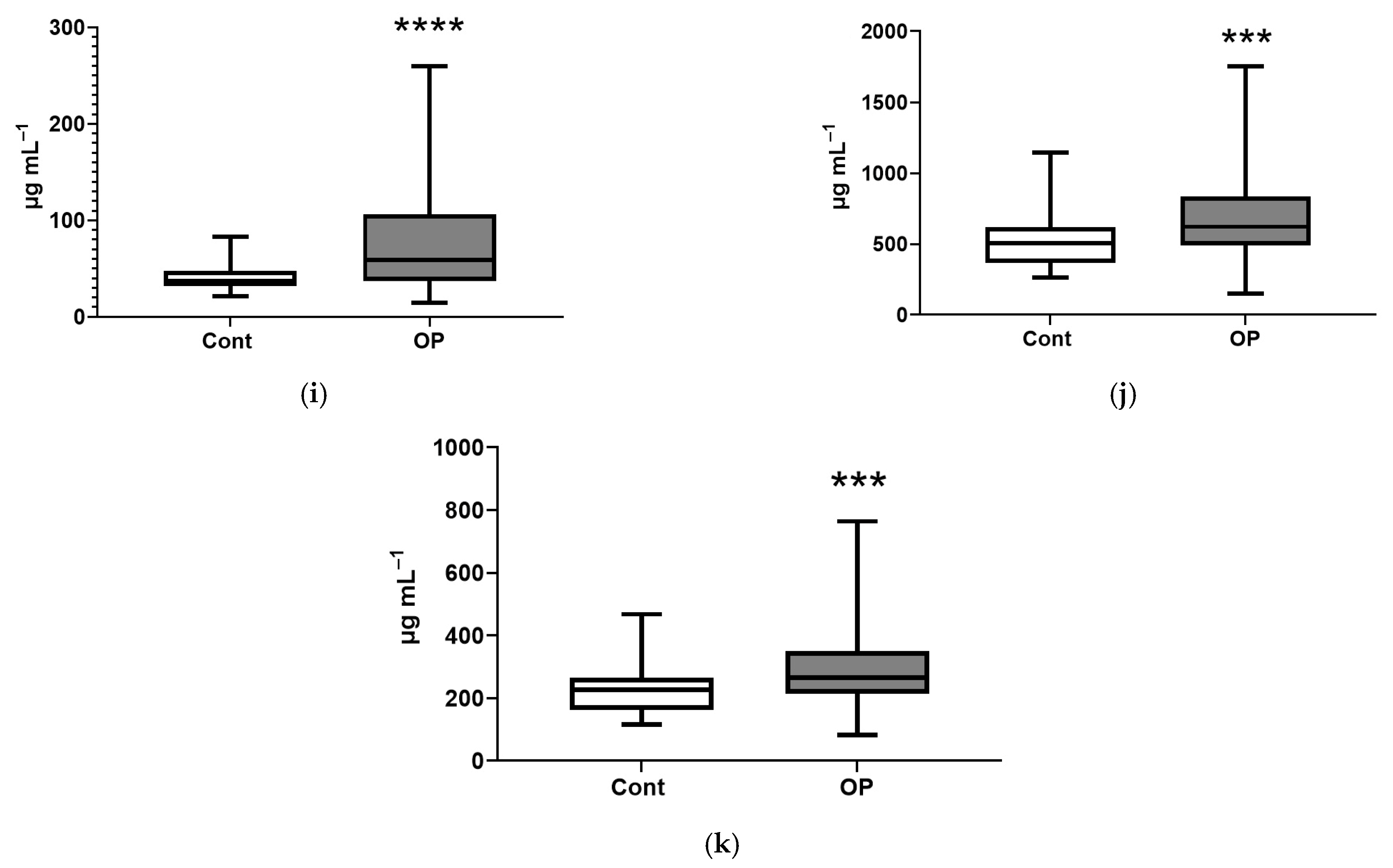

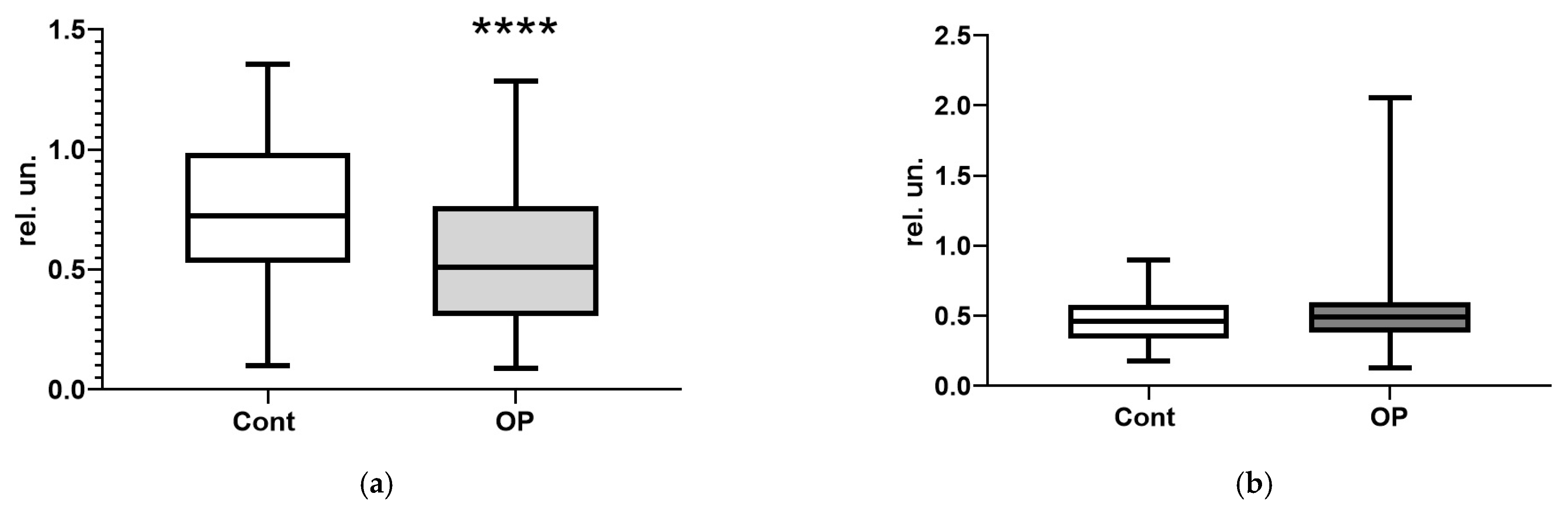

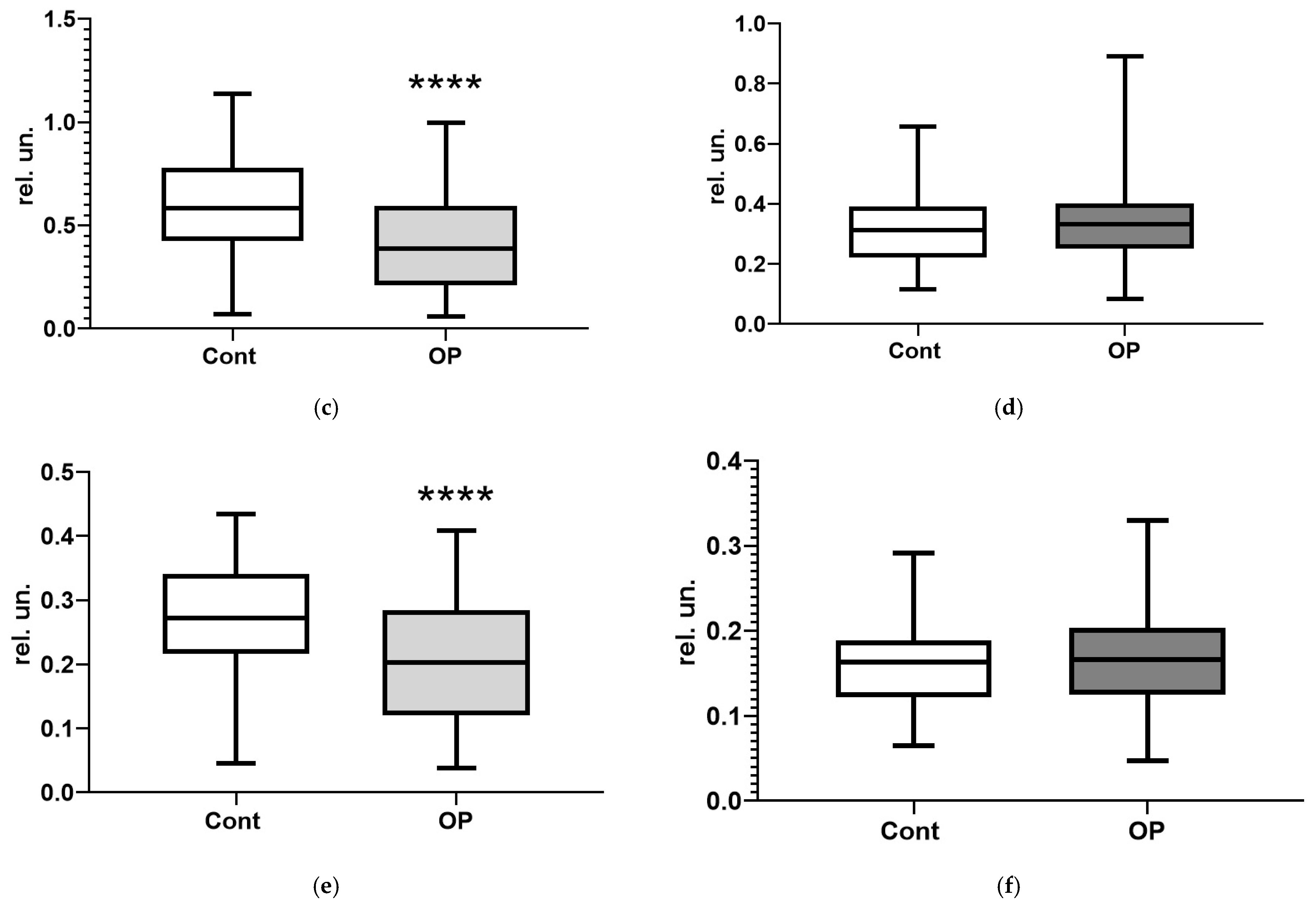

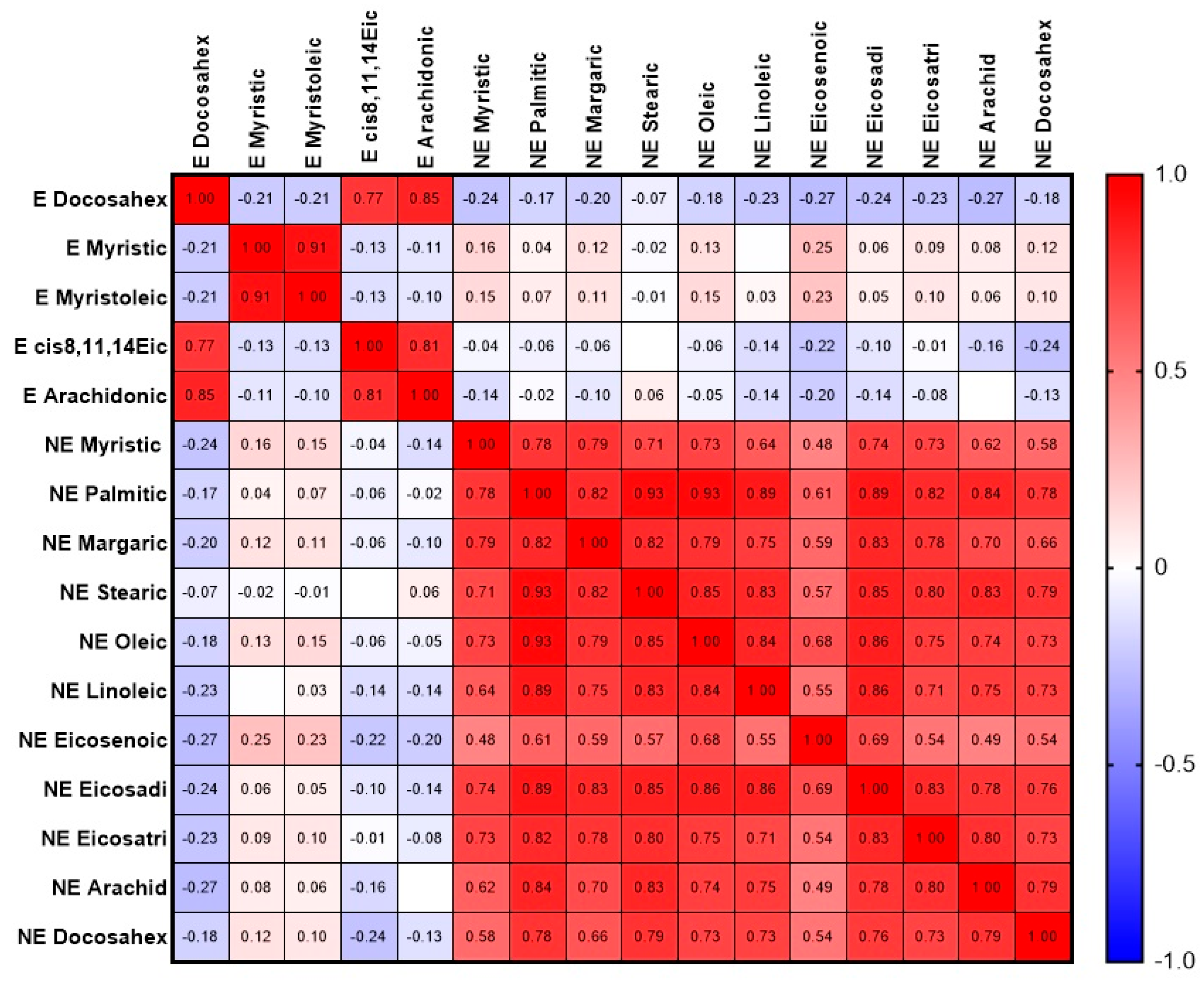

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data and Concomitant Diseases

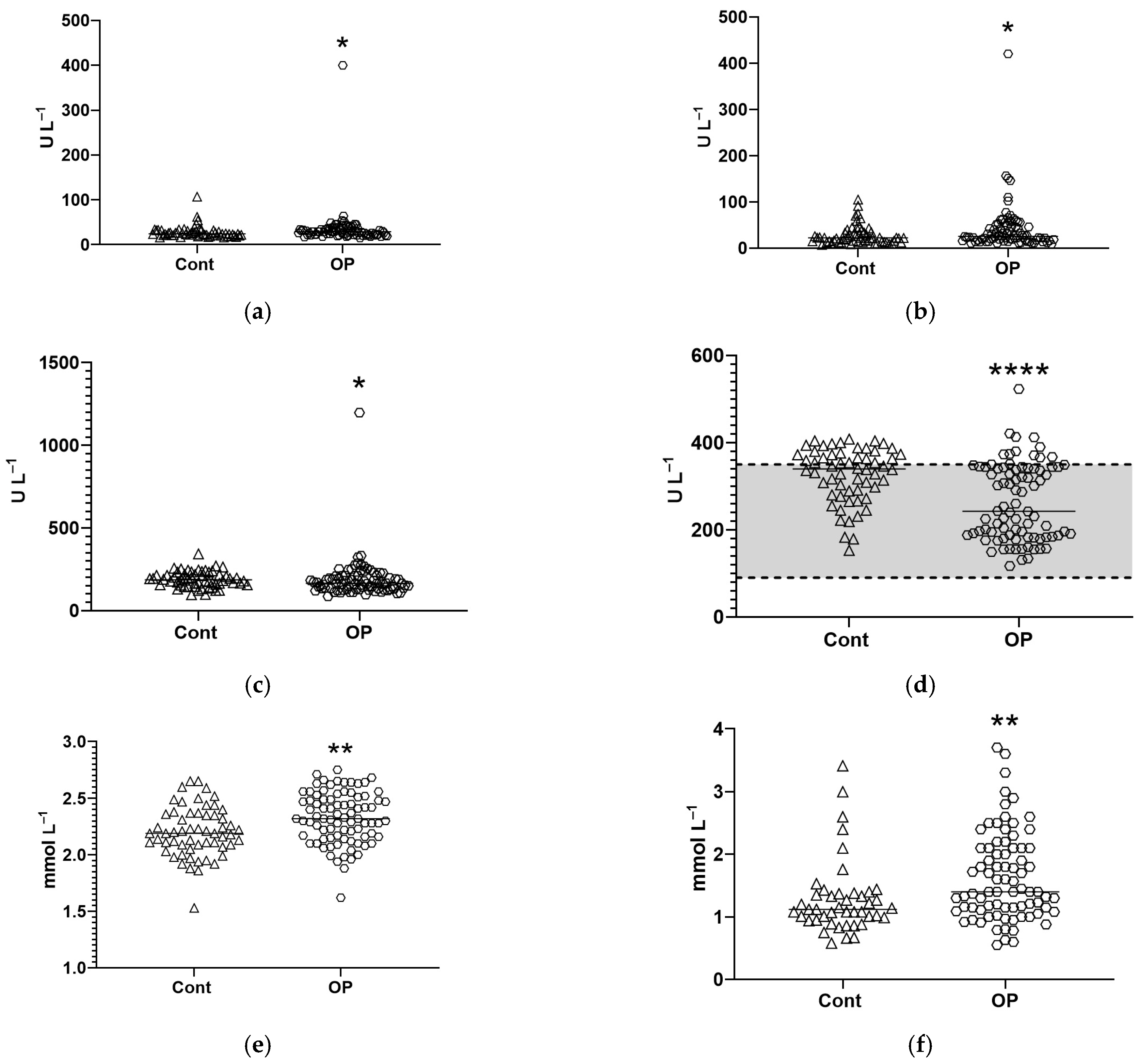

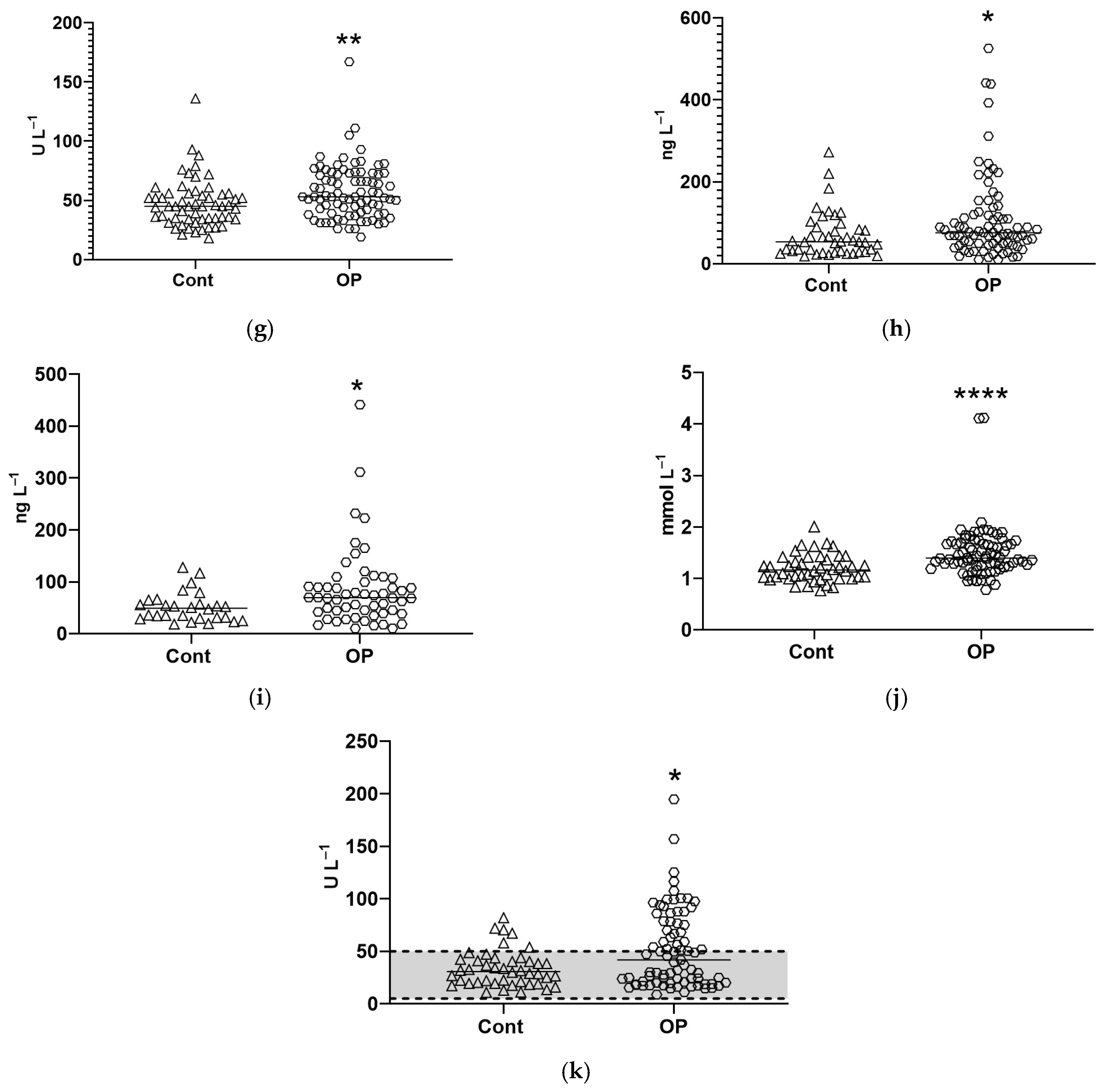

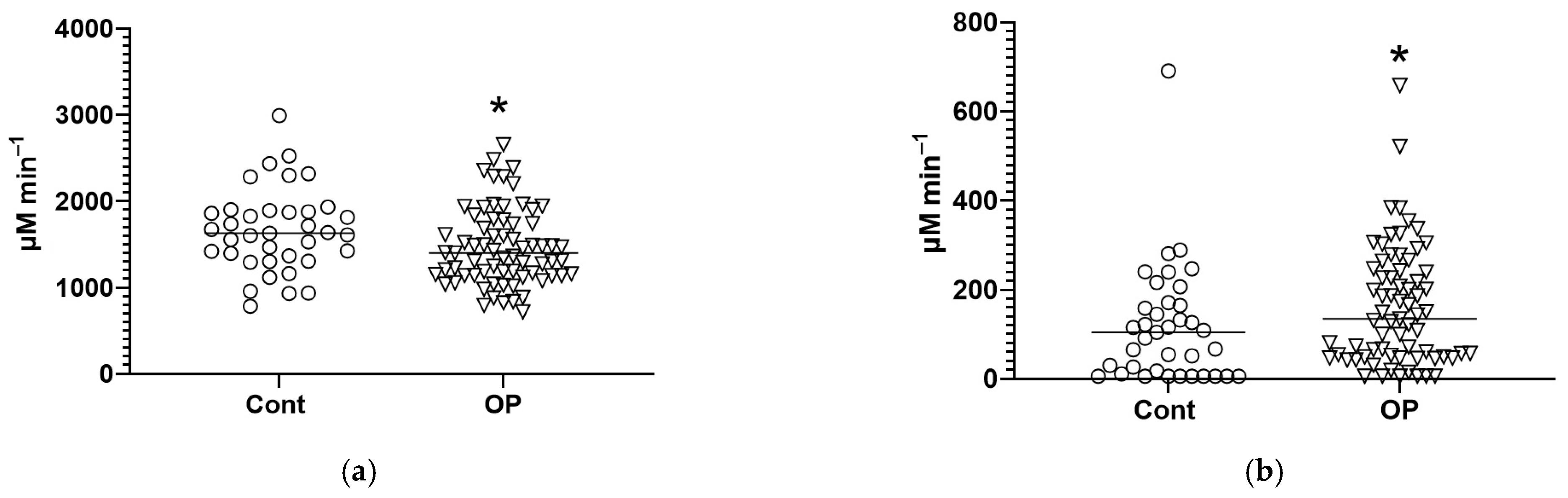

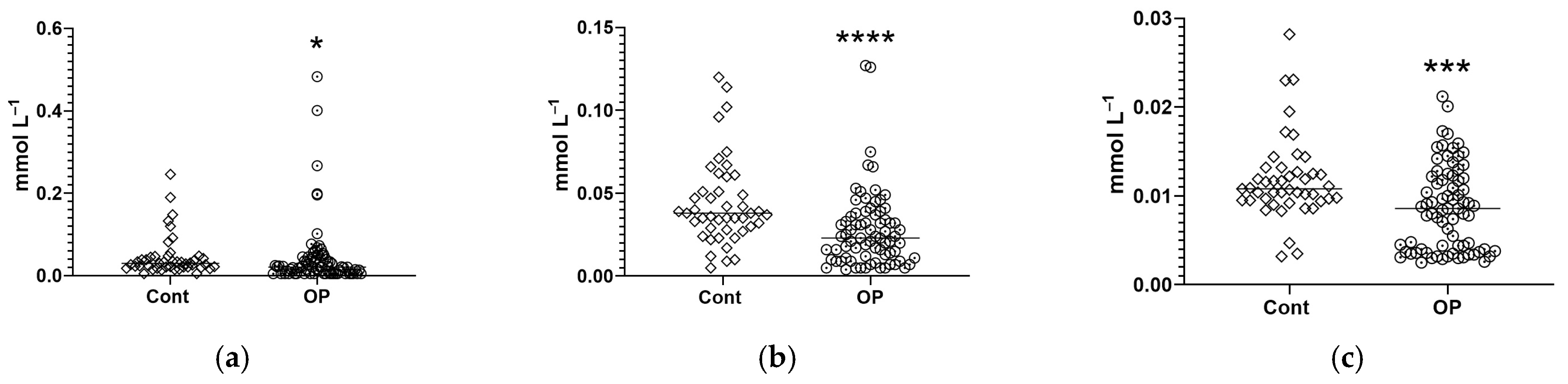

3.2. Biochemical Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALP | alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | aspartate aminotransferase |

| ATCh | acetylthiocholine |

| BChE | butyrylcholinesterase |

| BMI | body mass index |

| BTCh | butyrylthiocholine |

| EFA | esterified fatty acid |

| FA | fatty acid |

| GGT | gamma-glutamyltransferase |

| HDL | high-density lipoprotein |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MMSE | Mini Mental State Examination |

| NEFA | non-esterified fatty acid |

| OP | occupational pathology |

| PON1 | paraoxonase-1 |

| PUFA | polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| RMSD | root mean square deviation |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SAGE | Self-Administered Gerocognitive Exam |

| SCFA | short-chain fatty acid |

| SCSFA | short-chain saturated fatty acid |

| SFA | saturated fatty acid |

| TAS | total antioxidant status |

| VLDL | very low-density lipoprotein |

References

- Perez-Fernandez, C.; Flores, P.; Sánchez-Santed, F. A Systematic Review on the Influences of Neurotoxicological Xenobiotic Compounds on Inhibitory Control. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokanović, M.; Oleksak, P.; Kuca, K. Multiple neurological effects associated with exposure to organophosphorus pesticides in man. Toxicology 2023, 484, 153407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, P.C.; Cady, N.; Ghimire, S.; Shahi, S.K.; Shrode, R.L.; Lehmler, H.J.; Mangalam, A.K. Low-dose glyphosate exposure alters gut microbiota composition and modulates gut homeostasis. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 100, 104149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; AlHussaini, K.I. Pesticides: Unintended Impact on the Hidden World of Gut Microbiota. Metabolites 2024, 14, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, C.E.; Richter, R.; Marsillach, J.; Zelter, A.; McDonald, M.; Rettie, A.; Lockridge, O.; Lundeen, R.; Whittington, D. Investigating biomarkers of exposure to jet aircraft oil fumes using mass spectrometry. medRxiv 2025, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, X.; Lei, Y.; Jiang, X.; Kannan, K.; Li, M. Health Risks of Low-Dose Dietary Exposure to Triphenyl Phosphate and Diphenyl Phosphate in Mice: Insights from the Gut-Liver Axis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 8960–8971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokanović, M. Neurotoxic effects of organophosphorus pesticides and possible association with neurodegenerative diseases in man: A review. Toxicology 2018, 410, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, D.S.; Wu, X.; Singh, T.; Neff, M. Experimental Models of Gulf War Illness, a Chronic Neuropsychiatric Disorder in Veterans. Curr. Protoc. 2023, 3, e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neylon, J.; Fuller, J.N.; van der Poel, C.; Church, J.E.; Dworkin, S. Organophosphate Insecticide Toxicity in Neural Development, Cognition, Behaviour and Degeneration: Insights from Zebrafish. J. Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Belinskaia, D.A.; Avdonin, P.V. Organophospate-Induced Pathology: Mechanisms of Development, Principles of Therapy and Features of Experimental Studies. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2023, 59, 1756–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimani, A.; Ramezani, N.; Afkhami Goli, A.; Nazem Shirazi, M.H.; Nourani, H.; Jafari, A.M. Subchronic neurotoxicity of diazinon in albino mice: Impact of oxidative stress, AChE activity, and gene expression disturbances in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus on mood, spatial learning, and memory function. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, C.; Li, H.S. Effect of organophosphate pesticides poisoning on cognitive impairment. Chin. J. Ind. Hyg. Occup. Dis. 2021, 39, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, K. An Alternative Explanation for Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Initiation from Specific Antibiotics, Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Neurotoxins. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tattersall, J. Seizure activity post organophosphate exposure. Front. Biosci. 2009, 14, 3688–36711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Karami-Mohajeri, S. A comprehensive review on experimental and clinical findings in intermediate syndrome caused by organophosphate poisoning. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 258, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, G.J.; Wegner, J. Endothelial Glycocalyx and Cardiopulmonary Bypass. J. Extra Corpor. Technol. 2017, 49, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kori, R.K.; Singh, M.K.; Jain, A.K.; Yadav, R.S. Neurochemical and Behavioral Dysfunctions in Pesticide Exposed Farm Workers: A Clinical Outcome. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2018, 33, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.C.R.; Deshpande, L.S. A review of pre-clinical models for Gulf War Illness. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 228, 107936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Popova, P.I.; Kudryavtsev, I.V.; Golovkin, A.S.; Savitskaya, I.V.; Avdonin, P.P.; Korf, E.A.; Voitenko, N.G.; Belinskaia, D.A.; Serebryakova, M.K.; et al. Immunological Profile and Markers of Endothelial Dysfunction in Elderly Patients with Cognitive Impairments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, M.D.; Kisler, K.; Montagne, A.; Toga, A.W.; Zlokovic, B.V. The role of brain vasculature in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 1318–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Popova, P.I.; Nadeev, A.D.; Belinskaia, D.A.; Korf, E.A.; Avdonin, P.V. Endothelium, Aging, and Vascular Diseases. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 60, 2191–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Nadeev, A.D.; Jenkins, R.O.; Avdonin, P.V. Markers and Biomarkers of Endothelium: When Something Is Rotten in the State. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 9759735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, S.; He, H. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in patients with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim. Care Diabetes 2020, 14, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumora, A.E.; Kim, B.; Feldman, E.L. A Role for Fatty Acids in Peripheral Neuropathy Associated with Type 2 Diabetes and Prediabetes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2022, 37, 560–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, W.S.; Westra, J.; Tintle, N.L.; Sala-Vila, A.; Wu, J.H.; Marklund, M. Plasma n6 polyunsaturated fatty acid levels and risk for total and cause-specific mortality: A prospective observational study from the UK Biobank. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 120, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sala-Vila, A.; Tintle, N.; Westra, J.; Harris, W.S. Plasma Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Risk for Incident Dementia in the UK Biobank Study: A Closer Look. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retrato, M.D.C.; Nguyen, A.V.; Ubhayasekera, S.J.K.A.; Bergquist, J. Comprehensive quantification of C4 to C26 free fatty acids using a supercritical fluid chromatography-mass spectrometry method in pharmaceutical-grade egg yolk powders intended for total parenteral nutrition use. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2025, 417, 1461–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, H.O.; Nehme, R.; Limirio, L.S.; Mendonça, M.E.F.; de Branco, F.M.S.; de Oliveira, E.P. Plasma saturated fatty acids are inversely associated with lean mass and strength in adults: NHANES 2011-2012. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2025, 204, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, C.D.C.; Lust, C.A.C.; Burns, J.L.; Hillyer, L.M.; Martin, S.A.; Wittert, G.A.; Ma, D.W.L. Analysis of major fatty acids from matched plasma and serum samples reveals highly comparable absolute and relative levels. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2021, 168, 102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.W.; Mcfadden, S.L.; Machin, S.J.; Simson, E.; International Consensus Group for Hematology. The international consensus group for hematology review: Suggested criteria for action following automated CBC and WBC differential analysis. Lab. Hematol. 2005, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlova, T.I.; Ukolov, A.I.; Savel’eva, E.I.; Radilov, A.S. GC-MS quantification of free and esterified fatty acids in blood plasma. Anal. Control. 2015, 19, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merinov, A.V.; Zhurba, O.M.; Alekseenko, A.N.; Kudaeva, I.V. Levels of fatty acids in blood plasma in workers with vibration disease. Hyg. Sanit. 2023, 102, 928–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukolov, A.I.; Orlova, T.I.; Savel’eva, E.I.; Radilov, A.S. Chromatographic–mass spectrometric determination of free fatty acids in blood plasma and urine using extractive alkylation. J. Anal. Chem. 2015, 70, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokofieva, D.S.; Voitenko, N.G.; Gustyleva, L.K.; Babakov, V.N.; Savelieva, E.I.; Jenkins, R.O.; Goncharov, N.V. Microplate spectroscopic methods for determination of the organophosphate soman. J. Environ. Monit. 2010, 12, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokofieva, D.S.; Jenkins, R.O.; Goncharov, N.V. Microplate biochemical determination of Russian VX: Influence of admixtures and avoidance of false negative results. Anal. Biochem. 2012, 424, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belinskaia, D.A.; Voronina, P.A.; Popova, P.I.; Voitenko, N.G.; Shmurak, V.I.; Vovk, M.A.; Baranova, T.I.; Batalova, A.A.; Korf, E.A.; Avdonin, P.V.; et al. Albumin Is a Component of the Esterase Status of Human Blood Plasma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belinskaia, D.A.; Voronina, P.A.; Shmurak, V.I.; Batalova, A.A.; Goncharov, N.V.; Vovk, M.A.; Jenkins, R.O. Esterase activity of serum albumin studied by 1HNMR spectroscopy and molecular modelling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gall, W.E.; Beebe, K.; Lawton, K.A.; Adam, K.P.; Mitchell, M.W.; Nakhle, P.J.; Ryals, J.A.; Milburn, M.V.; Nannipieri, M.; Camastra, S.; et al. Alpha-hydroxybutyrate is an early biomarker of insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in a nondiabetic population. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraswathi, V.; Kumar, N.; Ai, W.; Gopal, T.; Bhatt, S.; Harris, E.N.; Talmon, G.A.; Desouza, C.V. Myristic Acid Supplementation Aggravates High Fat Diet-Induced Adipose Inflammation and Systemic Insulin Resistance in Mice. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, T.; Weinberger, B.; Memon, N.; Carayannopoulos, M.; Huber, A.H.; Kleinfeld, A.M. Plasma unbound free fatty acid profiles in premature infants before and after intralipid infusion. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal Med. 2020, 33, 2320–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, D.; Chen, L.; Ye, W.; Yang, Q.; Ling, Y. Cholinesterase is Associated With Prognosis and Response to Chemotherapy in Advanced Gastric Cancer. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2021, 27, 580800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, G.R.; Gumpeny, L. Emerging significance of butyrylcholinesterase. World, J. Exp. Med. 2024, 14, 87202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaki, S.; Fukuhara, T.; Mori, N.; Tsuji, K. High cholinesterase predicts tolerance to sorafenib treatment and improved prognosis in patients with transarterial chemoembolization refractory intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 12, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klocker, E.V.; Barth, D.A.; Riedl, J.M.; Prinz, F.; Szkandera, J.; Schlick, K.; Kornprat, P.; Lackner, K.; Lindenmann, J.; Stöger, H.; et al. Decreased Activity of Circulating Butyrylcholinesterase in Blood Is an Independent Prognostic Marker in Pancreatic Cancer Patients. Cancers 2020, 12, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmicseková, K.; Bies Piváčková, L.; Kiliánová, Z.; Slobodová, Ľ.; Křenek, P.; Hrabovská, A. Aortic butyrylcholinesterase is reduced in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Physiol. Res. 2021, 70, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharov, N.V.; Avdonin, P.P.; Voitenko, N.G.; Voronina, P.A.; Popova, P.I.; Novozhilov, A.V.; Blinova, M.S.; Popkova, V.S.; Belinskaia, D.A.; Avdonin, P.V. Searching for New Biomarkers to Assess COVID-19 Patients: A Pilot Study. Metabolites 2023, 13, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadokoro, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Honmyo, N.; Kuroda, S.; Ohira, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Oishi, K.; Oshita, A.; Abe, T.; Onoe, T.; et al. Albumin-Butyrylcholinesterase as a Novel Prognostic Biomarker for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Post-hepatectomy: A Retrospective Cohort Study with the Hiroshima Surgical Study Group of Clinical Oncology. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 32, 1973–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemashkalova, E.L.; Permyakov, E.A.; Uversky, V.N.; Permyakov, S.E.; Litus, E.A. Effect of Cu2+ and Zn2+ ions on human serum albumin interaction with plasma unsaturated fatty acids. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 131, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hierons, S.J.; Marsh, J.S.; Wu, D.; Blindauer, C.A.; Stewart, A.J. The Interplay between Non-Esterified Fatty Acids and Plasma Zinc and Its Influence on Thrombotic Risk in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coverdale, J.P.C.; Katundu, K.G.H.; Sobczak, A.I.S.; Arya, S.; Blindauer, C.A.; Stewart, A.J. Ischemia-modified albumin: Crosstalk between fatty acid and cobalt binding. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2018, 135, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blache, D.; Bourdon, E.; Salloignon, P.; Lucchi, G.; Ducoroy, P.; Petit, J.M.; Verges, B.; Lagrost, L. Glycated albumin with loss of fatty acid binding capacity contributes to enhanced arachidonate oxygenation and platelet hyperactivity: Relevance in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2015, 64, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzelac, T.; Smiljanić, K.; Takić, M.; Šarac, I.; Oggiano, G.; Nikolić, M.; Jovanović, V. The Thiol Group Reactivity and the Antioxidant Property of Human Serum Albumin Are Controlled by the Joint Action of Fatty Acids and Glucose Binding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zhang, J.; Wei, H.; Meng, X.; Ding, Q.; Sun, F.; Cao, M.; Yin, L.; Pu, Y. Acetyl-l-carnitine partially prevents benzene-induced hematotoxicity and oxidative stress in C3H/He mice. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 51, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahedi, E.; Sadr, S.S.; Sanaeierad, A.; Roghani, M. Chronic acetyl-L-carnitine treatment alleviates behavioral deficits and neuroinflammation through enhancing microbiota derived-SCFA in valproate model of autism. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Hiyama, Y.; Yokoyama, M.; Yu, S.; Hu, Y.; Melford, K.; Bensadoun, A.; Goldberg, I.J. In vivo arterial lipoprotein lipase expression augments inflammatory responses and impairs vascular dilatation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008, 28, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirri, D.; Tian, S.; Tardajos-Ayllon, B.; Irving, S.E.; Donati, F.; Allen, S.P.; Mammoto, T.; Vilahur, G.; Kabir, L.; Bennett, J.; et al. EPAS1 Attenuates Atherosclerosis Initiation at Disturbed Flow Sites Through Endothelial Fatty Acid Uptake. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 822–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetarpal, S.A.; Vitali, C.; Levin, M.G.; Klarin, D.; Park, J.; Pampana, A.; Millar, J.S.; Kuwano, T.; Sugasini, D.; Subbaiah, P.V.; et al. Endothelial lipase mediates efficient lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Song, X.; He, T.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Airikenjiang, H.; Abulaiti, D.; Qiu, H.; Zhu, M.; Yang, J.; et al. Effect of Interactions Between Endothelial Lipase Gene Polymorphisms and Traditional Cardiovascular Risk Factors on Coronary Heart Disease Susceptibility. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 26, 37356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, A.; Togliatto, G.; Rosso, A.; Dentelli, P.; Olgasi, C.; Cotogni, P.; Brizzi, M.F. Increase of palmitic acid concentration impairs endothelial progenitor cell and bone marrow-derived progenitor cell bioavailability: Role of the STAT5/Part transcriptional complex. Diabetes 2013, 62, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Yu, C.X.; Song, B.; Cai, W.; Liu, C.; Guan, Q.B. Free fatty acids mediates human umbilical vein endothelial cells inflammation through toll-like receptor-4. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 2421–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Liu, Y.L.; Ye, F.; Xie, J.W.; Zeng, J.W.; Qin, L.; Xue, J.; Wang, Y.T.; Guo, K.M.; Ma, M.M.; et al. Free fatty acid-induced H2O2 activates TRPM2 to aggravate endothelial insulin resistance via Ca2+-dependent PERK/ATF4/TRB3 cascade in obese mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 143, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergani, L.; Baldini, F.; Khalil, M.; Voci, A.; Putignano, P.; Miraglia, N. New Perspectives of S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) Applications to Attenuate Fatty Acid-Induced Steatosis and Oxidative Stress in Hepatic and Endothelial Cells. Molecules 2020, 25, 4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Lee, S.D.; Ou, H.C.; Lai, S.C.; Cheng, Y.J. Eicosapentaenoic acid protects against palmitic acid-induced endothelial dysfunction via activation of the AMPK/eNOS pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 10334–10349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majkova, Z.; Layne, J.; Sunkara, M.; Morris, A.J.; Toborek, M.; Hennig, B. Omega-3 fatty acid oxidation products prevent vascular endothelial cell activation by coplanar polychlorinated biphenyls. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011, 251, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Z.; Wang, K.; Wang, J. Neuroprotective effect of sulforaphane on hyperglycemia-induced cognitive dysfunction through the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2024, 17, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; van Esch, B.C.A.M.; Wagenaar, G.T.M.; Garssen, J.; Folkerts, G.; Henricks, P.A.J. Pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of short chain fatty acids on immune and endothelial cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 831, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnarumma, D.; Di Salle, A.; Micalizzi, G.; Vento, F.; La Tella, R.; Iannotta, P.; Trovato, E.; Melone, M.A.B.; Rigano, F.; Donato, P.; et al. Human blood lipid profiles after dietary supplementation of different omega 3 ethyl esters formulations. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2023, 1231, 123922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachem, M.; Nacir, H. Emerging Role of Phospholipids and Lysophospholipids for Improving Brain Docosahexaenoic Acid as Potential Preventive and Therapeutic Strategies for Neurological Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K. Docosahexaenoic acid inhibits ischemic stroke to reduce vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2023, 167, 106733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, J.; Kannan, S.; Govindasamy, A. Structured form of DHA prevents neurodegenerative disorders: A better insight into the pathophysiology and the mechanism of DHA transport to the brain. Nutr. Res. 2021, 85, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Van, A.; Bernoud-Hubac, N.; Lagarde, M. Esterification of Docosahexaenoic Acid Enhances Its Transport to the Brain and Its Potential Therapeutic Use in Brain Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, G.; Ramprasath, T.; Swaminathan, K.; Mithieux, G.; Rajendhran, J.; Dhivakar, M.; Parthasarathy, A.; Babu, D.D.; Thumburaj, L.J.; Freddy, A.J.; et al. Gut microbial degradation of organophosphate insecticides-induces glucose intolerance via gluconeogenesis. Genome Biol. 2017, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia-Escote, L.; Basaure, P.; Biosca-Brull, J.; Cabré, M.; Blanco, J.; Pérez-Fernández, C.; Sánchez-Santed, F.; Domingo, J.L.; Colomina, M.T. APOE genotype and postnatal chlorpyrifos exposure modulate gut microbiota and cerebral short-chain fatty acids in preweaning mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 135, 110872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesnage, R.; Bowyer, R.C.E.; El Balkhi, S.; Saint-Marcoux, F.; Gardere, A.; Ducarmon, Q.R.; Geelen, A.R.; Zwittink, R.D.; Tsoukalas, D.; Sarandi, E.; et al. Impacts of dietary exposure to pesticides on faecal microbiome metabolism in adult twins. Environ. Health 2022, 21, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Bai, Y.; Yu, Y.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, G.; Li, G.; Yu, Y.; An, T. Maternal transfer of resorcinol-bis(diphenyl)-phosphate perturbs gut microbiota development and gut metabolism of offspring in rats. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Tan, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, G.; Wu, J. Maternal exposure to tris (2-chloroethyl) phosphate during pregnancy and suckling period alters gut microbiota and SCFAs metabolism in offspring of rats. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 383, 126777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockridge, O.; Schopfer, L.M. Review: Organophosphorus toxicants, in addition to inhibiting acetylcholinesterase activity, make covalent adducts on multiple proteins and promote protein crosslinking into high molecular weight aggregates. Chem Biol Interact. 2023, 376, 110460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orcholski, M.E.; Khurshudyan, A.; Shamskhou, E.A.; Yuan, K.; Chen, I.Y.; Kodani, S.D.; Morisseau, C.; Hammock, B.D.; Hong, E.M.; Alexandrova, L.; et al. Reduced carboxylesterase 1 is associated with endothelial injury in methamphetamine-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2017, 313, L252–L266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.S.; Liu, D.H.; Hou, H.N.; Yao, J.N.; Xiao, S.C.; Ma, X.R.; Li, P.Z.; Cao, Q.; Liu, X.K.; Zhou, Z.Q.; et al. Dietary pattern interfered with the impacts of pesticide exposure by regulating the bioavailability and gut microbiota. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zong, Y.; Chen, W.; Geng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Du, R.; He, Z. Ginsenoside Rg3 alleviates brain damage caused by chlorpyrifos exposure by targeting and regulating the microbial-gut-brain axis. Phytomedicine 2025, 143, 156838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control | OP | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Data | ||

| Number of people examined | 59 | 84 |

| Men, n (%) | 17 (29) | 24 (29) |

| Women, n (%) | 42 (71) | 60 (71) |

| Age, m ± SD | 73 ± 4 | 74 ± 4 |

| BMI, m ± SD | 28.4 ± 4.1 | 30.0 ± 4.6 * |

| BMI within normal range (18.5–25), n (%) | 13 (22.0) | 13 (16.1) |

| Overweight (BMI 25–30), n (%) | 27 (45.8) | 28 (34.5) |

| Obesity grade 1 (BMI 30–35), n (%) | 14 (23.7) | 29 (35.8) |

| Obesity grade 2 (BMI 35–40), n (%) | 4 (6.8) | 9 (11.1) |

| Obesity grade 3, n (%) (BMI 40 and more) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (2.5) |

| Proportion of smokers, n (%) | 2 (3.4) | 12 (14.6) * |

| Education (higher), n (%) | 8 (14.5) | 8 (10.4) |

| Education (secondary specialized), n (%) | 33 (60.0) | 56 (72.7) |

| Education (secondary), n (%) | 14 (25.5) | 13 (16.9) |

| Drug load | 4 (3; 5) 0–20 | 5 (3; 8) *** 2–12 |

| Diseases | ||

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 20 (34) | 38 (46) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 55 (95) | 75 (91) |

| Gastrointestinal diseases, n (%) Including hepatitis, n (%) | 19 (32) 4 (7) | 45 (54) * 27 (33) *** |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 10 (17) | 19 (23) |

| Oncological diseases, n (%) | 3 (5) | 4 (5) |

| Musculoskeletal system diseases, n (%) | 54 (92) | 78 (95) |

| Acute cerebrovascular accident or chronic cerebrovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 54 (92) | 78 (95) |

| Total with diagnosis of polyneuropathy Including diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 39 (66) | 71 (87) ** |

| 8 (21) | 16 (23) | |

| Polyneuropathy of the upper and lower extremities, n (%) | 7 (12) | 24 (29) * |

| Response | Control | OP | |

| Self-assessment of memory and thinking problems, n (%) | Yes | 23 (41.8) | 45 (56.2) |

| Sometimes | 25 (45.5) | 31 (38.8) | |

| No | 7 (12.7) | 4 (5.0) | |

| Self-assessment of balance problems, n (%) | Yes | 38 (69) | 66 (84) * |

| No | 17 (31) | 13 (16) | |

| Self-assessment of feelings of anxiety, melancholy, depression, n (%) | Yes | 24 (43.6) | 45 (56.3) |

| Sometimes | 25 (43.6) | 25 (31.2) | |

| No | 7 (12.8) | 10 (12.5) | |

| Self-assessment of personality change, n (%) | Yes | 28 (50.9) | 39 (48.8) |

| No | 2 (3.6) | 8 (10.0) | |

| Do not know | 25 (45.5) | 33 (41.2) | |

| Self-assessment of difficulty in performing daily activities, n (%) | Yes | 27 (49) | 59 (75) ** |

| No | 28 (51) | 20 (25) | |

| Data after grouping | |||

| There are problems with memory and thinking, n (%) | 48 (87) | 76 (95) | |

| There is a feeling of anxiety, melancholy, or depression, n (%) | 48 (87) | 70 (87) | |

| There are personality changes, n (%) | 28 (53) | 39 (54) | |

| Control | OP | |

|---|---|---|

| MMSE | 27 (26; 28) 21–30 | 27 (26; 28) 13–31 |

| SAGE | 16 (12; 18) 6–21 | 16 (12; 18) 5–21 |

| “Clock” test | 9 (8; 10) 4–10 | 8 (7; 9) 4–10 |

| Total score for three tests | 51 (47; 54) 39–60 | 50 (46; 55) 24–61 |

| Control (n = 59) | OP (n = 82) | |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective symptoms (0 to 9) | 8 (6; 9) 1–9 | 8 (7; 9) * 3–9 |

| Presence of pathological foot reflexes, n (%) | 4 (7) | 6 (7) |

| Presence of pathological wrist reflexes, n (%) | 1 (2) | 10 (12) * |

| Impaired coordination (0 to 3 signs) | 2 (2; 2) 0–3 | 2 (2; 3) 1–3 |

| Cranial changes (0 to 6 signs) | 2 (1; 2) 0–4 | 2 (1; 3) *** 0–5 |

| Vibration sensitivity disorder, n (%) | 47 (80) | 77 (94) * |

| Impaired distal sensitivity, n (%) | 33 (56) | 68 (83) *** |

| Depression/absence of abdominal reflexes, n (%) | 39 (66) 15 (25) | 55 (67) 21 (26) |

| Depression/absence of Achilles reflexes, n (%) | 20 (34) 24 (41) | 34 (41) 22 (27) |

| Depression/absence of plantar reflexes, n (%) | 28 (47) 21 (36) | 30 (37) 30 (37) |

| Hypothermia of the extremities, n (%) | 4 (7) | 5 (6) |

| Hyperhidrosis of the extremities, n (%) | 26 (44) | 31 (38) |

| Spearman Correlation Coefficient for Full Array, n = 104 | Spearman Correlation Coefficient for Controls Only, n = 36 | Spearman Correlation Coefficient for OP Group Only, n = 68 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palmitic | 0.3842 (0.2014–0.5412) p < 0.0001 (****) | −0.0301 (−0.3639–0.3106) p = 0.8617 | 0.4936 (0.2826–0.6590) p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Stearic | 0.3488 (0.1619–0.5116) p = 0.0003 (***) | −0.0221 (−0.3569–0.3178) p = 0.8984 | 0.4501 (0.2303–0.6261) p = 0.0001 (***) |

| Oleic | 0.3281 (0.1390–0.4941) p = 0.0003 (***) | −0.0410 (−0.3733–0.3007) p = 0.8124 | 0.4391 (0.2173–0.6178) p = 0.0002 (***) |

| Linoleic | 0.3530 (0.1665–0.5151) p = 0.0002 (***) | −0.05136 (−0.3822–0.2912) p = 0.7661 | 0.4695 (0.2535–0.6409) p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Arachidonic | 0.4956 (0.3299–0.6317) p < 0.0001 (****) | 0.1300 (−0.2171–0.4478) p = 0.4500 | 0.6364 (0.4635–0.7626) p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Docosahexaenoic | 0.46264 (02909–0.6051) p < 0.0001 (****) | 0.0991 (−0.2467–0.4225) p = 0.5653 | 0.5472 (0.3488–0.06986) p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Sum of arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids | 0.4823 (0.3142–0.6211) p < 0.0001 (****) | 0.0978 (−0.2479–0.4214) p = 0.5704 | 0.5993 (0.04151–0.7363) p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Sum of six NEFAs | 0.4334 (0.2573–0.5816) p < 0.0001 (****) | −0.0158 (−0.3515–0.3234) p = 0.9270 | 0.5564 (0.3604–0.7054) p < 0.0001 (****) |

| Name of Acid | EFA, % | NEFA, % |

|---|---|---|

| Myristic, C14:0 | 159 ** | 138 **** |

| Myristoleic, C14:1 | 168 *** | |

| Pentadecanoic, C15:1 | 110 * | |

| Palmitic, C16:0 | 124 *** | |

| Palmitoleic, C16:1n-7 | 120 * | |

| Margaric, C17:0 | 67 ** | 110 ** |

| Heptadecenoic, C17:1 | 171 **** | |

| Stearic, C18:0 | 78 * | 120 ** |

| Oleic, C18:1n9c | 127 ** | |

| Linoelaidic, C18:2t | 122 ** | |

| Linoleic, C18:2n6c | 125 ** | |

| γ-Linolenic, C18:3n6 | 149 ** | |

| Eicosenoic, C20:1 | 137 ** | |

| Eicosadienoic, C20:2 | 80 ** | 128 *** |

| Eicosatrienoic, C20:3n8 | 66 ** | 156 *** |

| Erucic, C22:1n9 | 112 ** | |

| Arachidonic, C20:4n6 | 73 *** | 128 ** |

| Eicosapentaenoic, C20:5 | 156 * | |

| Docosahexaenoic, C22:6n3 | 41 **** | 149 ** |

| Sum of major | 77 ** | 130 *** |

| Sum of submajor | 68 * | 144 *** |

| Sum of minor | 158 **** | |

| Sum of long chain | 123 *** | |

| Sum of extra long chain | 52 **** | 157 *** |

| Sum of saturated FAs | 117 *** | |

| Sum of unsaturated FAs | 72 ** | 144 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goncharov, N.V.; Savelieva, E.I.; Koneva, T.A.; Gustyleva, L.K.; Vasilieva, I.A.; Belyakov, M.V.; Voitenko, N.G.; Belinskaia, D.A.; Korf, E.A.; Jenkins, R.O. Characteristics of the Fatty Acid Composition in Elderly Patients with Occupational Pathology from Organophosphate Exposure. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243246

Goncharov NV, Savelieva EI, Koneva TA, Gustyleva LK, Vasilieva IA, Belyakov MV, Voitenko NG, Belinskaia DA, Korf EA, Jenkins RO. Characteristics of the Fatty Acid Composition in Elderly Patients with Occupational Pathology from Organophosphate Exposure. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243246

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoncharov, Nikolay V., Elena I. Savelieva, Tatiana A. Koneva, Lyudmila K. Gustyleva, Irina A. Vasilieva, Mikhail V. Belyakov, Natalia G. Voitenko, Daria A. Belinskaia, Ekaterina A. Korf, and Richard O. Jenkins. 2025. "Characteristics of the Fatty Acid Composition in Elderly Patients with Occupational Pathology from Organophosphate Exposure" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243246

APA StyleGoncharov, N. V., Savelieva, E. I., Koneva, T. A., Gustyleva, L. K., Vasilieva, I. A., Belyakov, M. V., Voitenko, N. G., Belinskaia, D. A., Korf, E. A., & Jenkins, R. O. (2025). Characteristics of the Fatty Acid Composition in Elderly Patients with Occupational Pathology from Organophosphate Exposure. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243246