Myocardial Scar and Cardiac Biomarker Levels as Predictors of Mortality After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A CMR-Based Long-Term Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging

2.2. Image Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. CMR Findings

3.2. Prediction of LGE

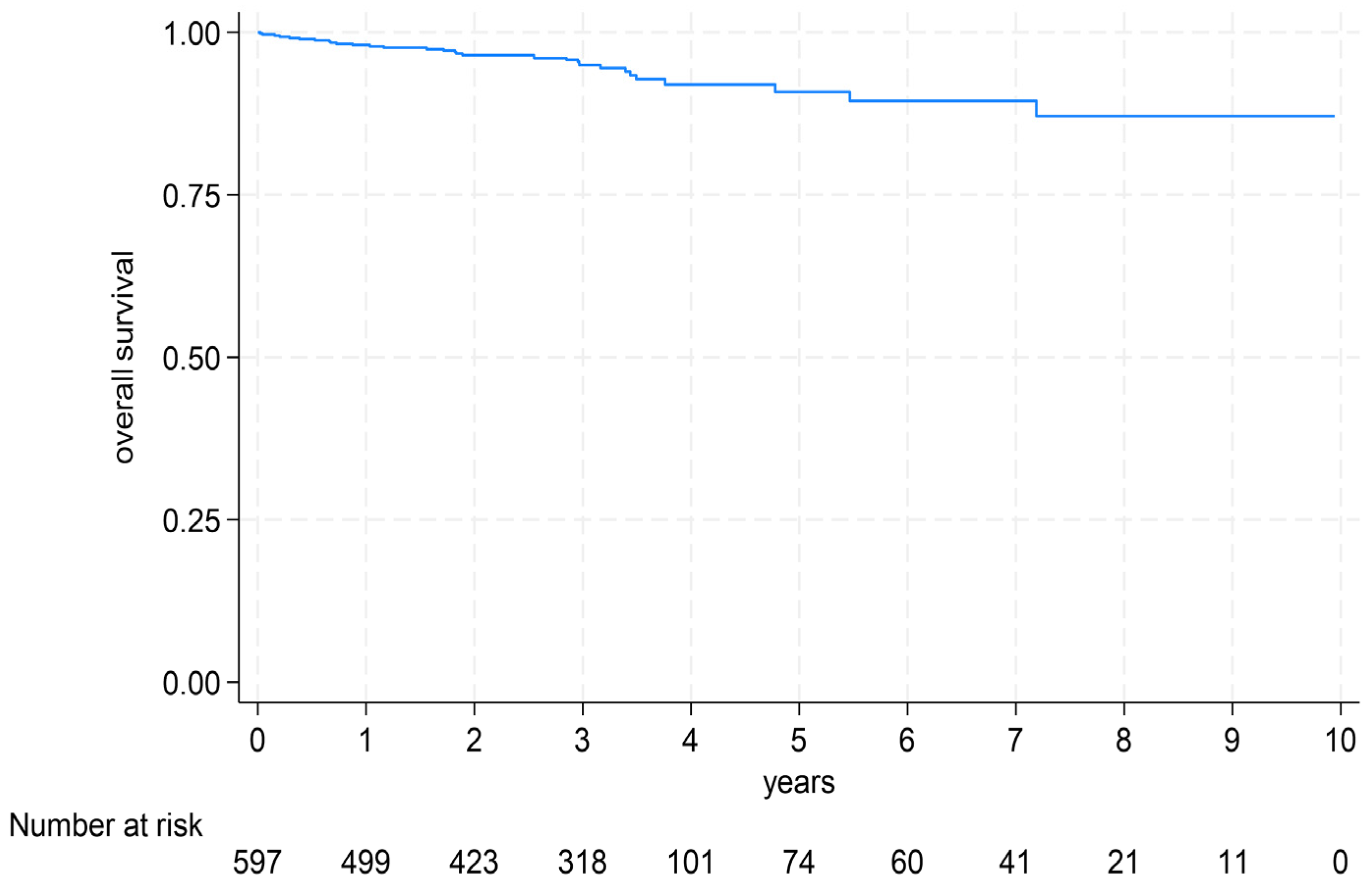

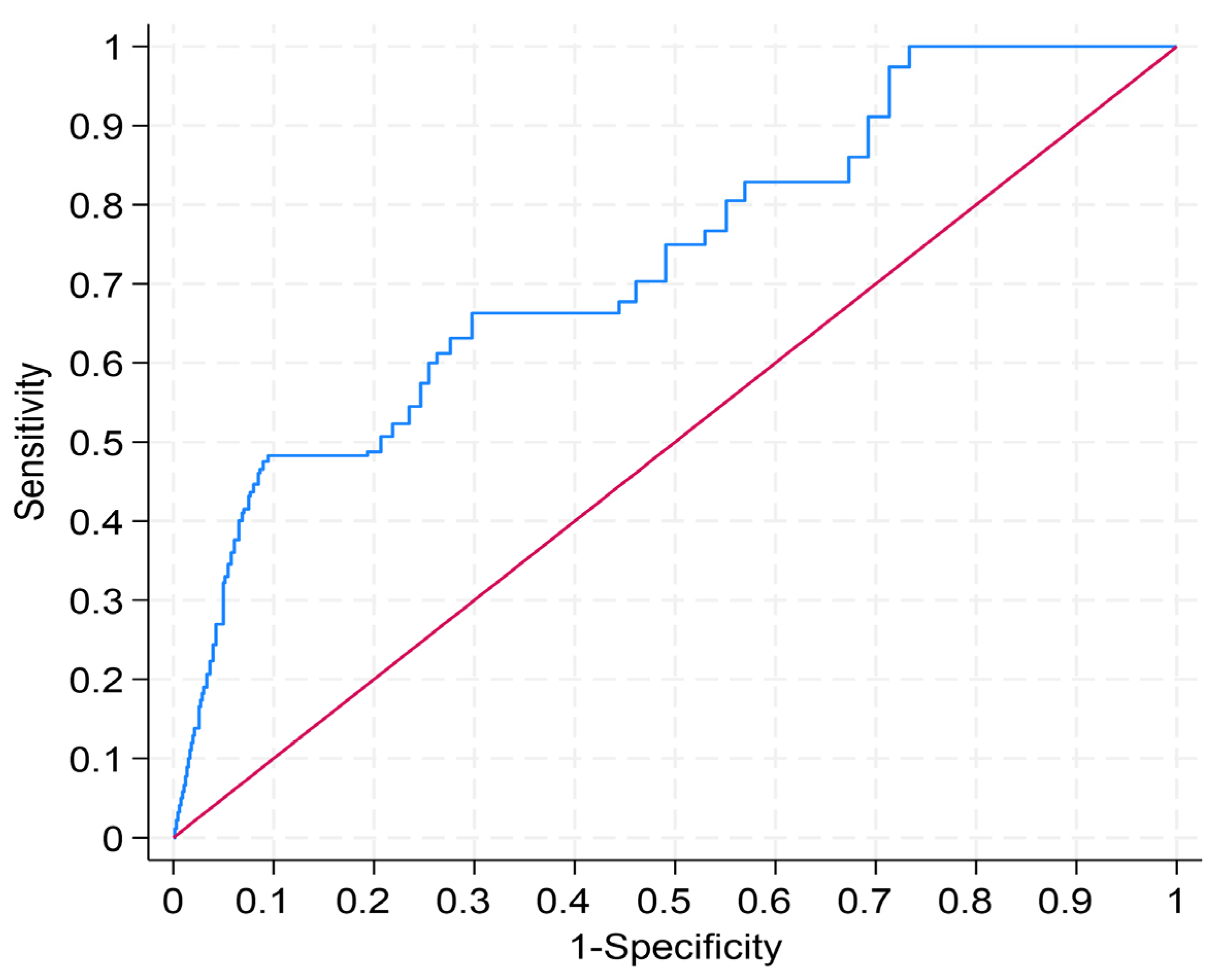

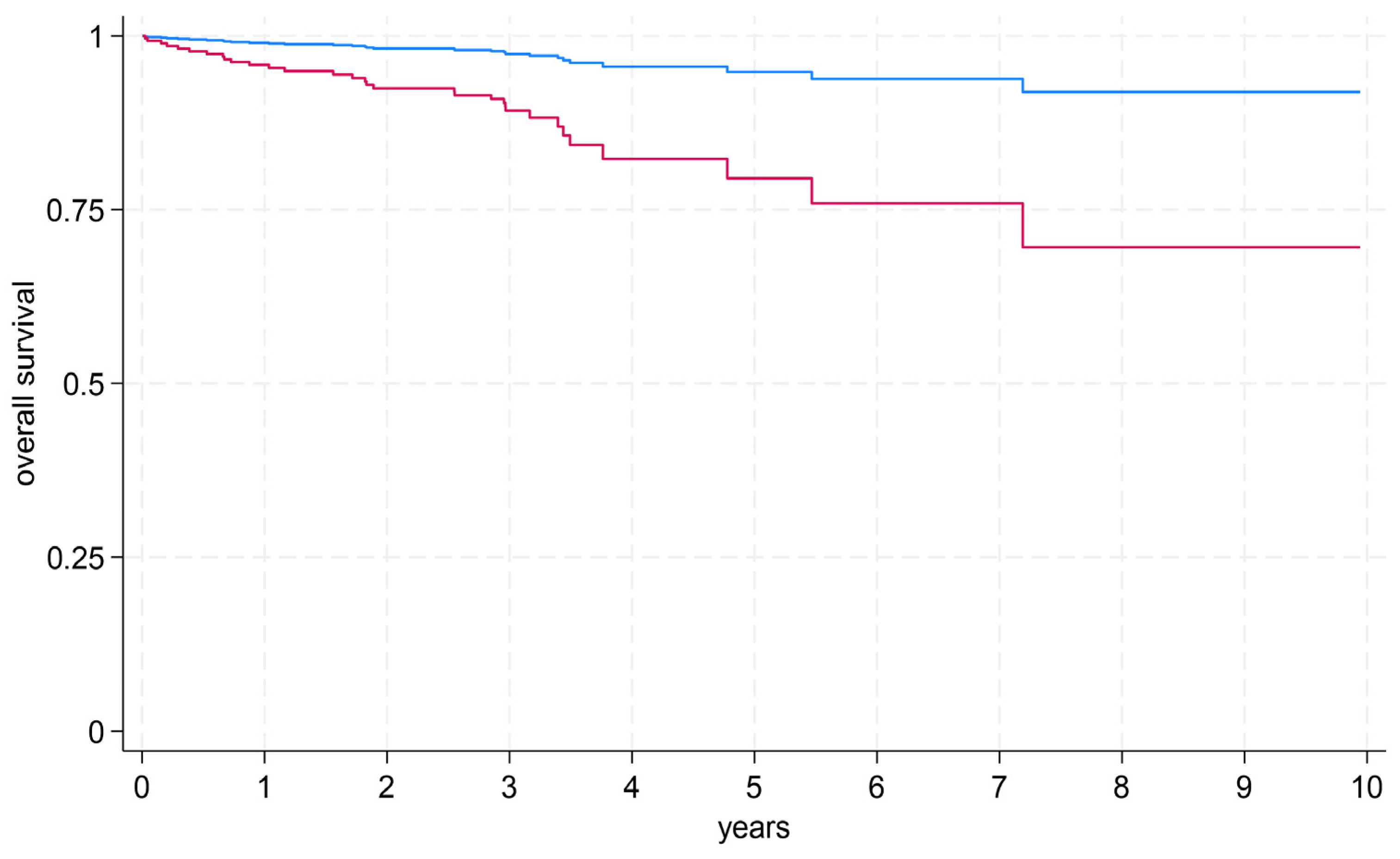

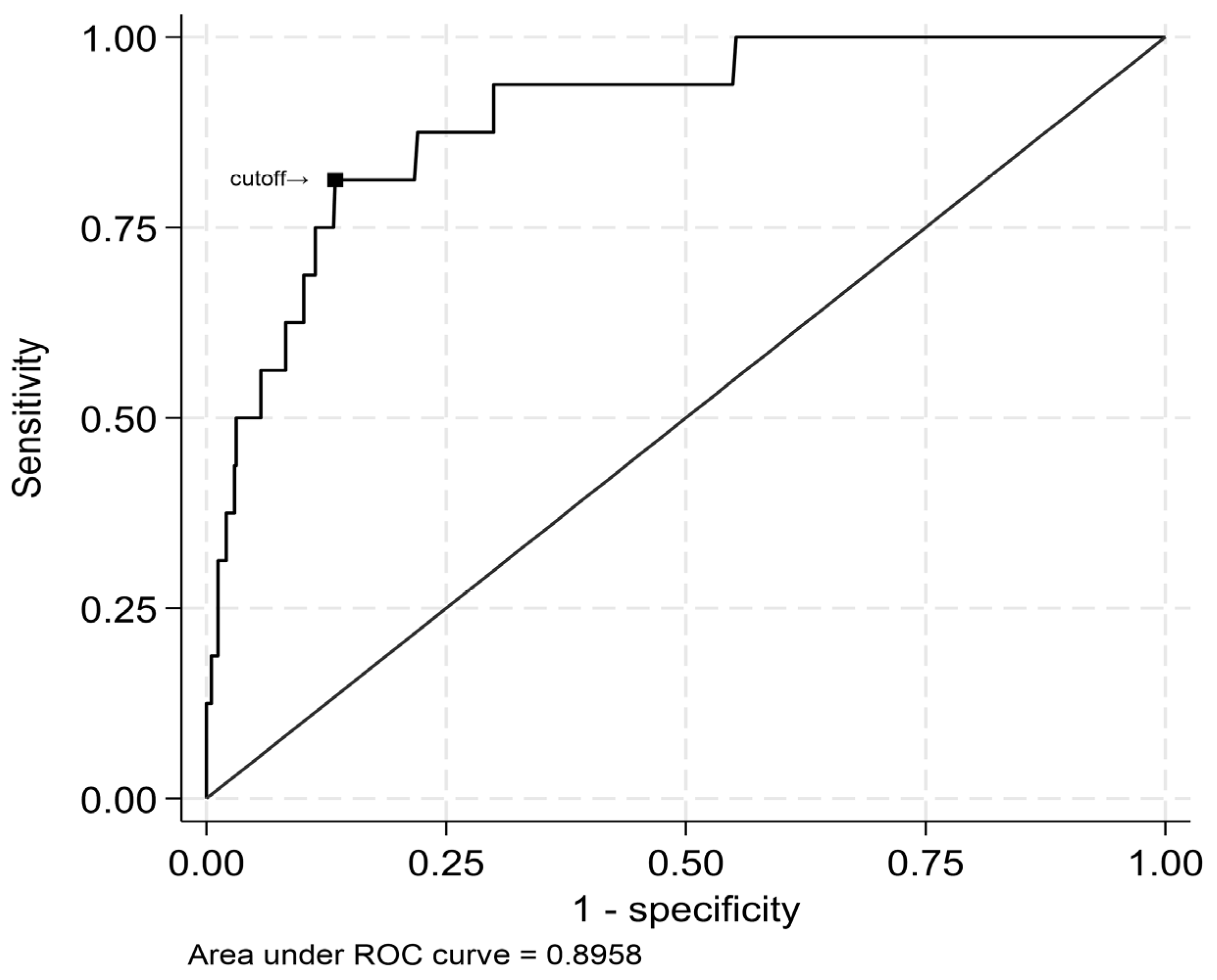

3.3. Prediction of Survival (By MRI and Biomarkers)

4. Discussion

- •

- A strong correlation was observed between peak cardiac biomarker levels and both the presence and extent of myocardial scar tissue in patients with acute MI.

- •

- Absolute LGE mass (in grams) and LVEF emerged as robust predictors of all-cause mortality with comparable predictive value.

- •

- LGE mass of ≥53 g was strongly associated with elevated risk of all-cause mortality, and a peak hs-cTnT level of ≥7270 ng/L accurately predicted this extent of myocardial damage.

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CK | creatine kinase |

| CMR | cardiac magnetic resonance imaging |

| hs-cTnT | high-sensitivity cardiac Troponin T |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LGE | late gadolinium enhancement |

| LVEF | left ventricular ejection fraction |

| MACE | major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

| NSTEMI | non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction |

| ROC | receiver operating characteristics |

| SAX | short axis stack |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SSFP | steady state free precision |

| STEMI | ST-elevation myocardial infarction |

References

- Butler, J.; Hammonds, K.; Talha, K.M.; Alhamdow, A.; Bennett, M.M.; Bomar, J.V.A.; Ettlinger, J.A.; Traba, M.M.; Priest, E.L.; Schmedt, N.; et al. Incident heart failure and recurrent coronary events following acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, P.M.; Kellner, C.; Sörensen, N.A.; Lehmacher, J.; Toprak, B.; Schock, A.; Hartikainen, T.S.; Twerenbold, R.; Zeller, T.; Westermann, D.; et al. Long-term outcome of patients presenting with myocardial injury or myocardial infarction. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2025, 114, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmeyer, H.W.; Feld, J.; Köppe, J.; Faldum, A.; Dröge, P.; Ruhnke, T.; Günster, C.; Reinecke, H.; Padberg, J.-S. Sex-specific outcomes in acute myocardial infarction-associated cardiogenic shock treated with and without V-A ECMO: A retrospective German nationwide analysis from 2014 to 2018. Heart Vessel. 2025, 40, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2023 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 292 causes of death in 204 countries and territories and 660 subnational locations, 1990–2023: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1811–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, V.; Van den, J.; Mashkoor, Y.; Huang, H.; Garimella, V.; Khadka, S.; Kumar, T.; Jaiswal, A.; Aronow, W.; Banach, M.; et al. Global Trends in Ischemic Heart Disease-Related Mortality From 2000 to 2019. JACC Adv. 2025, 4, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, R.C.; Tong, X.; Vaughan, A.S.; Shah, N.S.; Khan, S.S.; Imoisili, O.E.; Loustalot, F.V.; Havor, E.M.; Carlson, S.A. Trends in Mortality Rates for Cardiovascular Disease Subtypes Among Adults, 2010–2023. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2025, 70, 108119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Leifheit, E.C.; Krumholz, H.M. Trends in 10-Year Outcomes Among Medicare Beneficiaries Who Survived an Acute Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2022, 7, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariss, R.W.; Minhas, A.M.K.; Issa, R.; Ahuja, K.R.; Patel, M.M.; Eltahawy, E.A.; Michos, E.D.; Fudim, M.; Nazir, S. Demographic and Regional Trends of Mortality in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction in the United States, 1999 to 2019. Am. J. Cardiol. 2022, 164, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuin, M.; Rigatelli, G.; Temporelli, P.; Di Fusco, S.A.; Colivicchi, F.; Pasquetto, G.; Bilato, C. Trends in acute myocardial infarction mortality in the European Union, 2012–2020. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2023, 30, 1758–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, C.; Meisinger, C.; Kirchberger, I.; Heier, M.; Kuch, B.; Thilo, C.; Linseisen, J.; Amann, U. Epidemiological trends in mortality, event rates and case fatality of acute myocardial infarction from 2004 to 2015: Results from the KORA MI registry. Ann. Med. 2021, 53, 2142–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmis, A.; Kazakiewicz, D.; Townsend, N.; Huculeci, R.; Aboyans, V.; Vardas, P. Global epidemiology of acute coronary syndromes. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.H.; Halley, C.M.; Carrigan, T.P.; Zysek, V.; Popovic, Z.B.; Setser, R.; Schoenhagen, P.; Starling, R.C.; Flamm, S.D.; Desai, M.Y. Extent of left ventricular scar predicts outcomes in ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with significantly reduced systolic function: A delayed hyperenhancement cardiac magnetic resonance study. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2009, 2, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, G.W.; Selker, H.P.; Thiele, H.; Patel, M.R.; Udelson, J.E.; Ohman, E.M.; Maehara, A.; Eitel, I.; Granger, C.B.; Jenkins, P.L.; et al. Relationship Between Infarct Size and Outcomes Following Primary PCI: Patient-Level Analysis from 10 Randomized Trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kranenburg, M.; Magro, M.; Thiele, H.; de Waha, S.; Eitel, I.; Cochet, A.; Cottin, Y.; Atar, D.; Buser, P.; Wu, E.; et al. Prognostic value of microvascular obstruction and infarct size, as measured by CMR in STEMI patients. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadamitzky, M.; Langhans, B.; Hausleiter, J.; Sonne, C.; Byrne, R.A.; Mehilli, J.; Kastrati, A.; Schömig, A.; Martinoff, S.; Ibrahim, T. Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging after acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in comparison with single-photon emission tomography using Tc99m-Sestamibi. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 15, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, A.; Garot, J.; Toupin, S.; Duhamel, S.; Sanguineti, F.; Hovasse, T.; Champagne, S.; Unterseeh, T.; Chevalier, B.; Akodad, M.; et al. Prognostic Value of Cardiac MRI Late Gadolinium Enhancement Granularity in Participants with Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. Radiology 2025, 314, e240806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brado, J.; Schmitt, R.; Hein, M.; Valina, C.; Steinhauer, C.; Soschynski, M.; Schuppert, C.; Schlett, C.L.; Neumann, F.-J.; Westermann, D.; et al. Predicting MRI-diagnosed microvascular obstruction and its long-term impact after acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, R.; Staats, C.; Kaier, K.; Ahlgrim, C.; Hein, M.; Brado, J.; Steinhoff, P.; Billig, H.; Soschynski, M.; Krauss, T.; et al. Correlation of greyzone fibrosis compared to troponin T and late gadolinium enhancement with survival and ejection fraction in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2025, 114, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegard, A.; Okafor, O.; de Bono, J.; Kalla, M.; Lencioni, M.; Marshall, H.; Hudsmith, L.; Qiu, T.; Steeds, R.; Stegemann, B.; et al. Myocardial Fibrosis as a Predictor of Sudden Death in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.-A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiller, C.; Reindl, M.; Holzknecht, M.; Klapfer, M.; Beck, A.; Henninger, B.; Mayr, A.; Klug, G.; Reinstadler, S.J.; Metzler, B. Biomarker assessment for early infarct size estimation in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 64, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitel, I.; de Waha, S.; Wöhrle, J.; Fuernau, G.; Lurz, P.; Pauschinger, M.; Desch, S.; Schuler, G.; Thiele, H. Comprehensive Prognosis Assessment by CMR Imaging After ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, H.; Giannitsis, E.; Futterer, S.; Merten, C.; Juenger, C.; Katus, H.A. Cardiac Troponin T at 96 Hours After Acute Myocardial Infarction Correlates With Infarct Size and Cardiac Function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 48, 2192–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, M.A.; Koul, S.; Smith, J.G.; Noc, M.; Lang, I.; Holzer, M.; Clemmensen, P.; Jensen, U.; Engstrøm, T.; Arheden, H.; et al. Predictive Value of High-Sensitivity Troponin T for Systolic Dysfunction and Infarct Size (Six Months) After ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2018, 122, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licka, M.; Zimmermann, R.; Zehelein, J.; Dengler, T.J.; Katus, H.A.; Kübler, W. Troponin T concentrations 72 hours after myocardial infarction as a serological estimate of infarct size. Heart 2002, 87, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleynikov, V.; Salyamova, L.; Alimov, N.; Donetskaya, N.; Avdeeva, I.; Averyanova, E. The Clinical Significance and Potential of Complex Diagnosis for a Large Scar Area Following Myocardial Infarction. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøysa, V.; Berg, G.J.; Singsaas, E.; Eftestøl, T.; Woie, L.; Ørn, S. Texture-based probability mapping for automatic assessment of myocardial injury in late gadolinium enhancement images after revascularized STEMI. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 427, 133107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, N.; Hindricks, G.; Akbarov, A.; Tijssen, J.G.P.; Jenkins, D.A.; Kapacee, Z.; Parkes, L.M.; van der Geest, R.J.; Longato, E.; Sprague, D.; et al. Sudden cardiac death after myocardial infarction: Individual participant data from pooled cohorts. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 4616–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, I.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C. MINOCA and CMR: Where Do We Stand? JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2023, 16, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | All Patients (N = 597) |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Age—yr | 63.9 ± 11.7 |

| Male sex—no. (%) | 466 (78.1) |

| Body mass index (IQR) † | 27.1 (24.8–29.7) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors—no. (%) | |

| Hypertension | 413 (69.2) |

| Dyslipidemia | 438 (73.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 113 (18.9) |

| Family predisposition | 166 (27.8) |

| Nicotine abuse | 312 (52.3) |

| Known CAD | 70 (11.7) |

| Laboratory values | |

| Hemoglobin—g/dL | 14.5 ± 4.0 |

| LDL-C—mg/dL | 141.2 ± 41.0 |

| GFR—mL/min/1.73 m2 (IQR) | 84.1 (67.8–97.1) |

| Maximum High-sensitivity Troponin T—ng/L (IQR) | 2440.0 (879.0–5050.0) |

| Maximum CK—U/L (IQR) | 979.0 (398.0–1925.0) |

| Maximum CK-MB—U/L (IQR) | 110.0 (47.0–220.0) |

| Infarct-related vessel | |

| LAD | 278 (46.6) |

| LCX | 91 (15.2) |

| RCA | 228 (38.2) |

| CMR findings | |

| Time between MI and CMR—days (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) |

| LGE—g (IQR) | 18.0 (7.0–34.0) |

| LVEF—% | 50.0 ± 10.0 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum High-sensitivity Troponin T—ng/L | 0.003 | 0.003 | ||||

| [0.003,0.004] | [0.002,0.003] | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| Maximum CK—U/L | 0.010 | 0.010 | ||||

| [0.009,0.012] | [0.008,0.011] | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| Maximum CK-MB—U/L | 0.083 | 0.081 | ||||

| [0.065,0.100] | [0.064,0.097] | |||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| Sex | −8.229 | −9.887 | −11.036 | |||

| [−10.927,−5.530] | [−12.463,−7.310] | [−13.889,−8.182] | ||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| Age | −0.193 | −0.030 | −0.084 | |||

| [−0.320,−0.066] | [−0.150,0.090] | [−0.215,0.048] | ||||

| (0.003) | (0.623) | (0.211) | ||||

| Type of myocardial infarction | 4.185 | 3.707 | 4.408 | |||

| [0.410,7.959] | [0.144,7.271] | [0.571,8.244] | ||||

| (0.030) | (0.041) | (0.024) | ||||

| Time between symptom onset and admission < 2 h | −0.918 | −0.634 | −1.516 | |||

| [−6.104,4.267] | [−5.439,4.170] | [−6.684,3.652] | ||||

| (0.728) | (0.795) | (0.565) | ||||

| Time between symptom onset and admission between 2 and 8 h | 0.985 | −0.437 | −1.006 | |||

| [−4.824,6.794] | [−6.483,5.610] | [−7.335,5.323] | ||||

| (0.739) | (0.887) | (0.755) | ||||

| Time between symptom onset and admission between 8 and 14 h | 3.796 | 1.287 | 3.075 | |||

| [−4.746,12.338] | [−5.902,8.475] | [−5.093,11.244] | ||||

| (0.383) | (0.725) | (0.460) | ||||

| Time between symptom onset and admission between >25 h | 3.377 | 5.884 | 5.544 | |||

| [−3.947,10.701] | [−1.123,12.892] | [−1.590,12.678] | ||||

| (0.366) | (0.100) | (0.127) | ||||

| Time between symptom onset and admission unknown | −1.346 | −0.611 | −1.110 | |||

| [−7.250,4.557] | [−6.010,4.788] | [−6.524,4.304] | ||||

| (0.654) | (0.824) | (0.687) | ||||

| Infarct-related vessel—LAD | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||

| [0.000,0.000] | [0.000,0.000] | [0.000,0.000] | ||||

| (.) | (.) | (.) | ||||

| Infarct-related vessel—LCX | 1.165 | 0.324 | 0.928 | |||

| [−3.420,5.749] | [−3.571,4.219] | [−3.451,5.306] | ||||

| (0.618) | (0.870) | (0.678) | ||||

| Infarct-related vessel—RCA | −1.177 | −1.597 | −1.147 | |||

| [−4.361,2.007] | [−4.719,1.525] | [−4.381,2.087] | ||||

| (0.468) | (0.315) | (0.486) | ||||

| Hs-CRP | 1.825 | 2.266 | 2.146 | |||

| [0.678,2.972] | [1.148,3.384] | [1.075,3.216] | ||||

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| Constant | 11.935 | 9.619 | 10.949 | 37.578 | 29.288 | 24.076 |

| [9.961,13.909] | [7.531,11.708] | [8.280,13.617] | [13.067,62.089] | [1.673,56.904] | [−3.458,51.611] | |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.003) | (0.038) | (0.086) | |

| Observations | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LGE mass | 1.267 | 1.464 | ||||||||||

| [0.935,1.717] | [1.050,2.040] | |||||||||||

| (0.127) | (0.025) | |||||||||||

| LGE proportion | 1.203 | 1.260 | ||||||||||

| [0.875,1.654] | [0.881,1.801] | |||||||||||

| (0.254) | (0.206) | |||||||||||

| Maximum High-sensitivity Troponin T—ng/L | 1.332 | 1.260 | ||||||||||

| [0.974,1.822] | [0.912,1.740] | |||||||||||

| (0.073) | (0.161) | |||||||||||

| Maximum CK—U/L | 1.064 | 1.203 | ||||||||||

| [0.755,1.499] | [0.843,1.717] | |||||||||||

| (0.722) | (0.308) | |||||||||||

| Maximum CK-MB—U/L | 1.001 | 1.031 | ||||||||||

| [0.677,1.480] | [0.687,1.548] | |||||||||||

| (0.998) | (0.881) | |||||||||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 0.686 | 0.697 | ||||||||||

| [0.488,0.966] | [0.491,0.990] | |||||||||||

| (0.031) | (0.044) | |||||||||||

| Sex (=female) | 1.141 | 1.021 | 1.006 | 0.986 | 0.987 | 1.025 | ||||||

| [0.519,2.510] | [0.472,2.209] | [0.465,2.173] | [0.458,2.126] | [0.457,2.132] | [0.476,2.210] | |||||||

| (0.742) | (0.958) | (0.988) | (0.972) | (0.974) | (0.949) | |||||||

| Age | 1.109 | 1.107 | 1.105 | 1.109 | 1.106 | 1.105 | ||||||

| [1.066,1.154] | [1.064,1.152] | [1.062,1.149] | [1.065,1.153] | [1.063,1.150] | [1.062,1.150] | |||||||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||||

| Type of myocardial infarction | 1.167 | 1.227 | 1.228 | 1.299 | 1.414 | 1.189 | ||||||

| [0.532,2.561] | [0.553,2.726] | [0.556,2.712] | [0.594,2.840] | [0.646,3.097] | [0.548,2.580] | |||||||

| (0.700) | (0.615) | (0.612) | (0.512) | (0.386) | (0.661) | |||||||

| Harrell’s C | 0.630 | 0.620 | 0.541 | 0.504 | 0.483 | 0.655 | 0.812 | 0.795 | 0.778 | 0.782 | 0.776 | 0.810 |

| Observations | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 | 597 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruile, P.; Brado, J.; Kaier, K.; Schmitt, R.; Hein, M.; Nührenberg, T.; Billig, H.; Neumann, F.-J.; Westermann, D.; Breitbart, P. Myocardial Scar and Cardiac Biomarker Levels as Predictors of Mortality After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A CMR-Based Long-Term Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243229

Ruile P, Brado J, Kaier K, Schmitt R, Hein M, Nührenberg T, Billig H, Neumann F-J, Westermann D, Breitbart P. Myocardial Scar and Cardiac Biomarker Levels as Predictors of Mortality After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A CMR-Based Long-Term Study. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243229

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuile, Philipp, Johannes Brado, Klaus Kaier, Ramona Schmitt, Manuel Hein, Thomas Nührenberg, Hannah Billig, Franz-Josef Neumann, Dirk Westermann, and Philipp Breitbart. 2025. "Myocardial Scar and Cardiac Biomarker Levels as Predictors of Mortality After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A CMR-Based Long-Term Study" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243229

APA StyleRuile, P., Brado, J., Kaier, K., Schmitt, R., Hein, M., Nührenberg, T., Billig, H., Neumann, F.-J., Westermann, D., & Breitbart, P. (2025). Myocardial Scar and Cardiac Biomarker Levels as Predictors of Mortality After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A CMR-Based Long-Term Study. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3229. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243229