Limitations of DNA Methylation Profiling in High-Grade Gliomas: Case Series †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Patients

2.2. Case Presentation

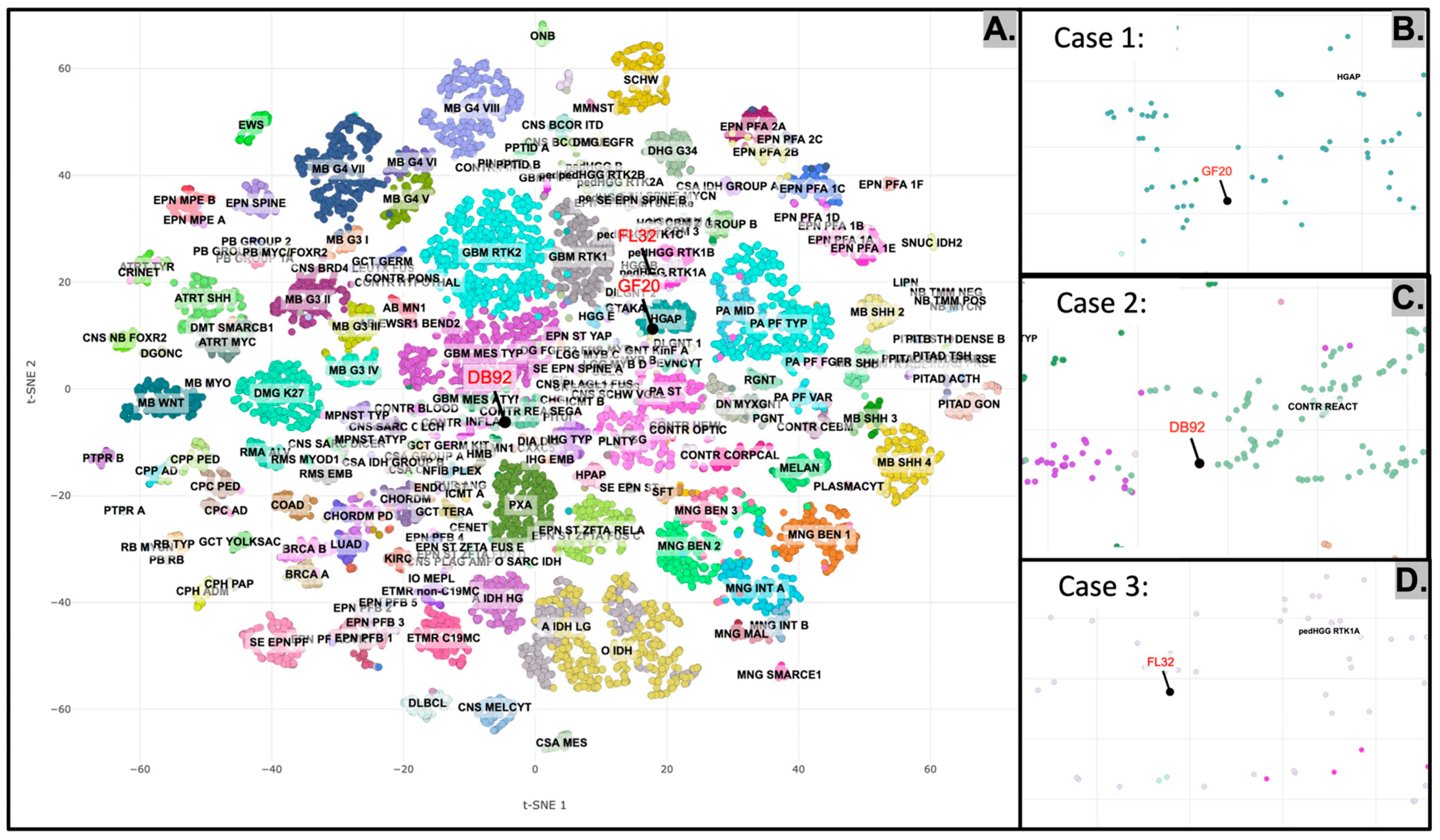

2.2.1. Case 1

2.2.2. Case 2

2.2.3. Case 3

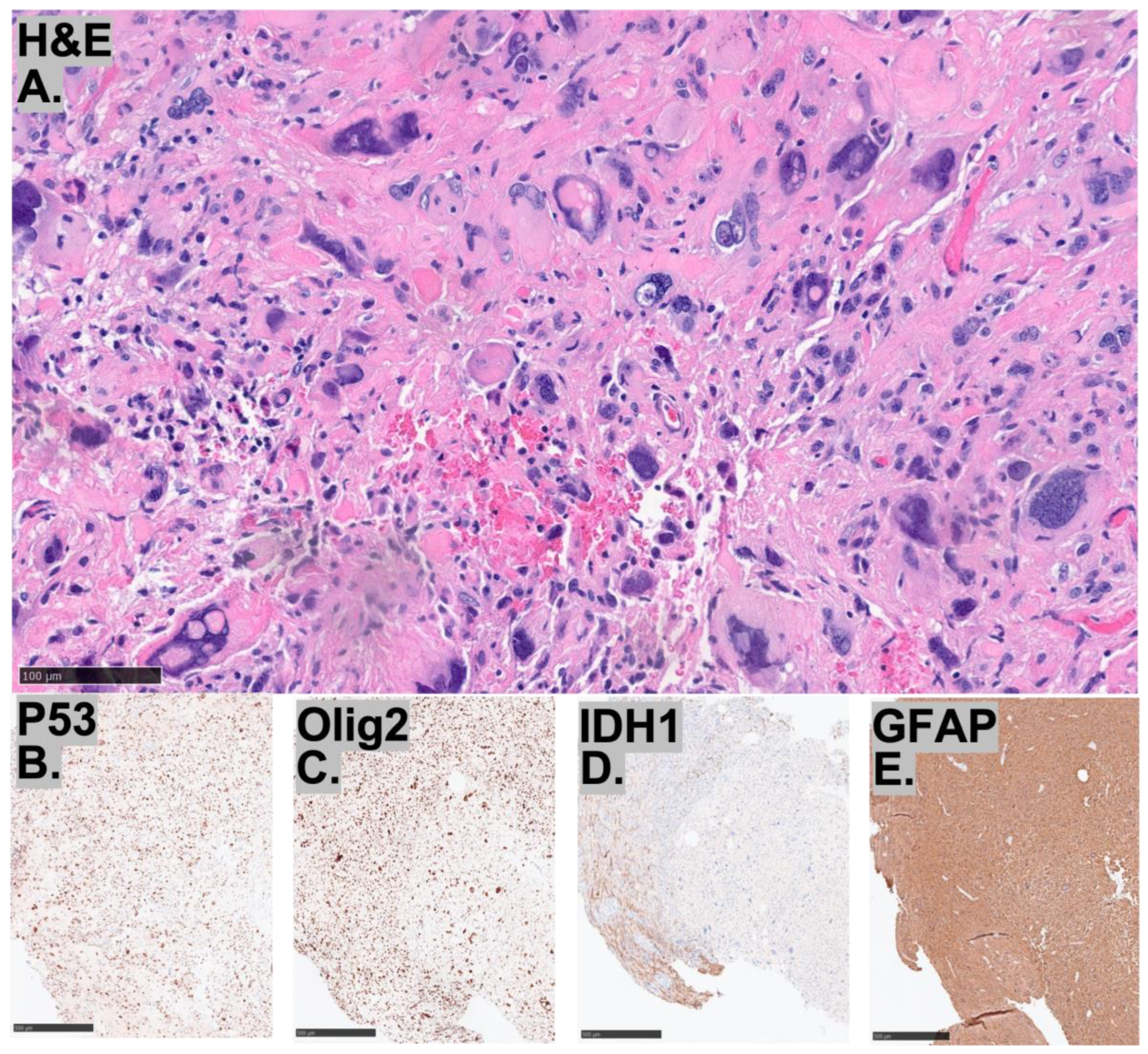

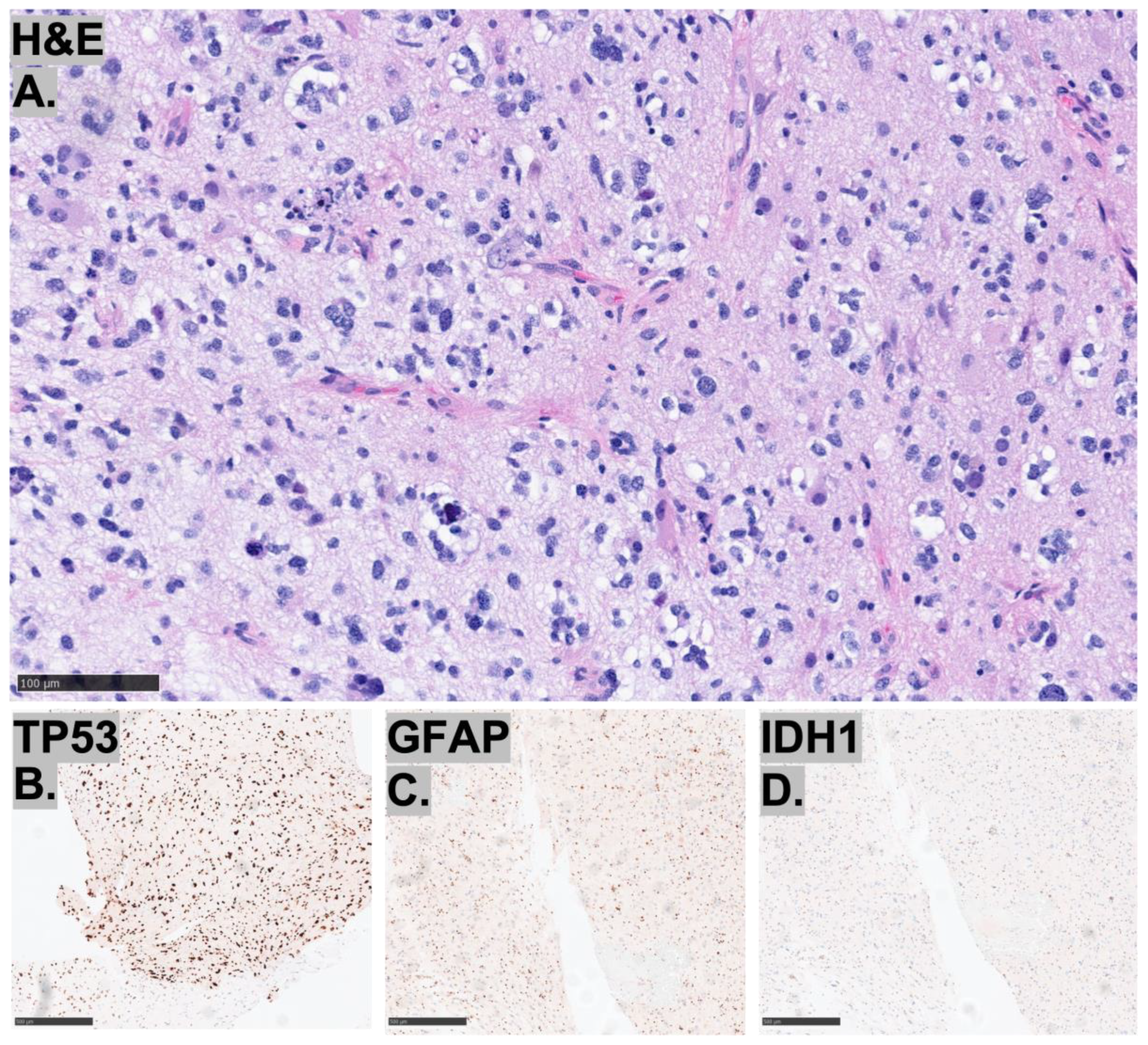

2.3. Histopathological Characteristics of the Tumors

2.4. Molecular Characteristics of the Tumors

2.5. DNA Methylation Profiling of the Tumors

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| HGG | High-Grade Gliomas |

References

- Aran, V.; Heringer, M.; da Mata, P.J.; Kasuki, L.; Miranda, R.L.; Andreiuolo, F.; Chimelli, L.; Filho, P.N.; Gadelha, M.R.; Neto, V.M. Identification of mutant K-RAS in pituitary macroadenoma. Pituitary 2021, 24, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capper, D.; Jones, D.T.W.; Sill, M.; Hovestadt, V.; Schrimpf, D.; Sturm, D.; Koelsche, C.; Sahm, F.; Chavez, L.; Reuss, D.E.; et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature 2018, 555, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, R.; Brembach, F.; Sauvigny, J.; Ricklefs, F.L.; Eckhardt, A.; Bode, H.; Gempt, J.; Lamszus, K.; Westphal, M.; Schüller, U.; et al. Unclassifiable CNS tumors in DNA methylation-based classification: Clinical challenges and prognostic impact. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, K.; Vasudevaraja, V.; Serrano, J.; Shen, G.; Tran, I.; Abdallat, N.; Wen, M.; Patel, S.; Movahed-Ezazi, M.; Faustin, A.; et al. Clinical utility of whole-genome DNA methylation profiling as a primary molecular diagnostic assay for central nervous system tumors—A prospective study and guidelines for clinical testing. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2023, 5, vdad076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Santos, L.; Kam, K.L.; Dittmann, D.; De Vito, S.; McCord, M.; Jamshidi, P.; Fowler, H.; Wang, X.; Aalsburg, A.M.; Brat, D.J.; et al. Validation of Whole Genome Methylation Profiling Classifier for Central Nervous System Tumors. J. Mol. Diagn. JMD 2022, 24, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barresi, V.; Poliani, P.L. When do I ask for a DNA methylation array for primary brain tumor diagnosis? Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2024, 36, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertero, L.; Mangherini, L.; Ricci, A.A.; Cassoni, P.; Sahm, F. Molecular neuropathology: An essential and evolving toolbox for the diagnosis and clinical management of central nervous system tumors. Virchows Arch. Int. J. Pathol. 2024, 484, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kling, T.; Ferreyra Vega, S.; Suman, M.; Dénes, A.; Lipatnikova, A.; Lagerström, S.; Olsson Bontell, T.; Jakola, A.S.; Carén, H. Refinement of prognostication for IDH-mutant astrocytomas using DNA methylation-based classification. Brain Pathol. Zur. Switz. 2024, 34, e13233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priesterbach-Ackley, L.P.; Boldt, H.B.; Petersen, J.K.; Bervoets, N.; Scheie, D.; Ulhøi, B.P.; Gardberg, M.; Brännström, T.; Torp, S.H.; Aronica, E.; et al. Brain tumour diagnostics using a DNA methylation-based classifier as a diagnostic support tool. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2020, 46, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Abdullaev, Z.; Pratt, D.; Chung, H.-J.; Skarshaug, S.; Zgonc, V.; Perry, C.; Pack, S.; Saidkhodjaeva, L.; Nagaraj, S.; et al. Impact of the methylation classifier and ancillary methods on CNS tumor diagnostics. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 24, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, R.; Schüller, U.; Eckhardt, A.; Filipski, K.; Hartung, T.I.; Harter, P.N.; Divé, I.; Forster, M.-T.; Czabanka, M.; Jelgersma, C.; et al. DNA methylation subclasses predict the benefit from gross total tumor resection in IDH-wildtype glioblastoma patients. Neuro-Oncology 2023, 25, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgacheva, D.; Ryzhova, M.; Zheludkova, O.; Belogurova, M.; Dinikina, Y. DNA methylation-based diagnosis confirmation in a pediatric patient with low-grade glioma: A case report. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1256876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: A summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbinski, C.; Solomon, D.A.; Lukas, R.V.; Packer, R.J.; Brastianos, P.; Wen, P.Y.; Snuderl, M.; Berger, M.S.; Chang, S.; Fouladi, M.; et al. Molecular Testing for the World Health Organization Classification of Central Nervous System Tumors: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2025, 11, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajtler, K.W.; Witt, H.; Sill, M.; Jones, D.T.W.; Hovestadt, V.; Kratochwil, F.; Wani, K.; Tatevossian, R.; Punchihewa, C.; Johann, P.; et al. Molecular Classification of Ependymal Tumors across All CNS Compartments, Histopathological Grades, and Age Groups. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 728–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, A.; Stichel, D.; Schrimpf, D.; Sahm, F.; Korshunov, A.; Reuss, D.E.; Koelsche, C.; Huang, K.; Wefers, A.K.; Hovestadt, V.; et al. Anaplastic astrocytoma with piloid features, a novel molecular class of IDH wildtype glioma with recurrent MAPK pathway, CDKN2A/B and ATRX alterations. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahm, F.; Schrimpf, D.; Stichel, D.; Jones, D.T.W.; Hielscher, T.; Schefzyk, S.; Okonechnikov, K.; Koelsche, C.; Reuss, D.E.; Capper, D.; et al. DNA methylation-based classification and grading system for meningioma: A multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Sahu, S.; Mohan, T.; Mahajan, S.; Sharma, M.C.; Sarkar, C.; Suri, V. Current status of DNA methylation profiling in neuro-oncology as a diagnostic support tool: A review. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2023, 10, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, D.; Capper, D.; Andreiuolo, F.; Gessi, M.; Kölsche, C.; Reinhardt, A.; Sievers, P.; Wefers, A.K.; Ebrahimi, A.; Suwala, A.K.; et al. Multiomic neuropathology improves diagnostic accuracy in pediatric neuro-oncology. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, O.C.H.; Ho, R.S.L.; Chan, S.; Li, K.K.W.; Lam, T.-L.; Cheung, E.T.Y.; Cheung, O.-Y.; Ho, W.W.S.; Cheng, K.K.F.; Shing, M.M.K.; et al. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Profiling as Frontline Diagnostics for Central Nervous System Embryonal Tumors in Hong Kong. Cancers 2023, 15, 4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, A.; Carén, H. Methylation Profiling in Diffuse Gliomas: Diagnostic Value and Considerations. Cancers 2022, 14, 5679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, D.; Sahm, F.; Aldape, K. DNA methylation profiling as a model for discovery and precision diagnostics in neuro-oncology. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, S16–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satomi, K.; Ichimura, K.; Shibahara, J. Decoding the DNA methylome of central nervous system tumors: An emerging modality for integrated diagnosis. Pathol. Int. 2024, 74, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gusyatiner, O.; Hegi, M.E. Glioma epigenetics: From subclassification to novel treatment options. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 51, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.G.; Alden, J.; Dubuc, A.M.; Welsh, C.T.; Znoyko, I.; Cooley, L.D.; Farooqi, M.S.; Schwartz, S.; Li, Y.Y.; Cherniack, A.D.; et al. Near haploidization is a genomic hallmark which defines a molecular subgroup of giant cell glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncol. Adv. 2020, 2, vdaa155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaubel, R.; Zschernack, V.; Tran, Q.T.; Jenkins, S.; Caron, A.; Milosevic, D.; Smadbeck, J.; Vasmatzis, G.; Kandels, D.; Gnekow, A.; et al. Biology and grading of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma-what have we learned about it? Brain Pathol. 2021, 31, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goethe, E.A.; Srinivasan, S.; Kumar, S.; Prabhu, S.S.; Gubbiotti, M.A.; Ferguson, S.D. High-grade astrocytoma with piloid features: A single-institution case series and literature review. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, L.; Gilis, N.; Dausort, M.; Gillard, C.; Rusu, S.; Slimani, K.; De Witte, O.; Escande, F.; Lefranc, F.; D’Haene, N.; et al. Diagnostic impact of DNA methylation classification in adult and pediatric CNS tumors. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarnio, M.; Sankila, R.; Pukkala, E.; Salovaara, R.; Aaltonen, L.A.; de la Chapelle, A.; Peltomäki, P.; Mecklin, J.P.; Järvinen, H.J. Cancer risk in mutation carriers of DNA-mismatch-repair genes. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 81, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, E.; Robinson, L.; Alduaij, W.; Shenton, A.; Clancy, T.; Lalloo, F.; Hill, J.; Evans, D.G. Cumulative lifetime incidence of extracolonic cancers in Lynch syndrome: A report of 121 families with proven mutations. Clin. Genet. 2009, 75, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasen, H.F.; Stormorken, A.; Menko, F.H.; Nagengast, F.M.; Kleibeuker, J.H.; Griffioen, G.; Taal, B.G.; Moller, P.; Wijnen, J.T. MSH2 mutation carriers are at higher risk of cancer than MLH1 mutation carriers: A study of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer families. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 4074–4080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therkildsen, C.; Ladelund, S.; Rambech, E.; Persson, A.; Petersen, A.; Nilbert, M. Glioblastomas, astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas linked to Lynch syndrome. Eur. J. Neurol. 2015, 22, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargav, A.G.; Domino, J.S.; Alvarado, A.M.; Tuchek, C.A.; Akhavan, D.; Camarata, P.J. Advances in computational and translational approaches for malignant glioma. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1219291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchlak, Q.D.; Esmaili, N.; Leveque, J.-C.; Bennett, C.; Farrokhi, F.; Piccardi, M. Machine learning applications to neuroimaging for glioma detection and classification: An artificial intelligence augmented systematic review. J. Clin. Neurosci. Off. J. Neurosurg. Soc. Australas. 2021, 89, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Pan, M.; Mo, K.; Mao, Y.; Zou, D. Emerging role of artificial intelligence in diagnosis, classification and clinical management of glioma. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 91, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, G.; La Cognata, V.; Guarnaccia, M.; Gentile, G.; Cavallaro, S. Artificial Intelligence-Driven Multi-Omics Approaches in Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, S.; Ming, J.; Chen, H.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, C. Integrating deep learning and radiomics for preoperative glioma grading using multi-center MRI data. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, M.; Chen, C.; Chen, L. Methylation Profiling Limitations for High Grade Brain Tumors. In Proceedings of the 2025 101st AANP Annual Meeting, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 19–22 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Histopathology | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATRX | + | + | + |

| p53 | overexpression | overexpression | overexpression |

| Ki-67 index | elevated | elevated | elevated |

| IDH1 | − | − | − |

| GFAP | + | + | + |

| Synaptophysin | weakly positive | ||

| Olig2 | − | patchy positivity | + |

| BRAF V600E | − | − | |

| H3K27M | − |

| Molecular | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IDH1/2 | − | − | − |

| TP53 | Normal | Pathologic mutation | Pathologic mutation |

| ATRX | − | − | − |

| BRAF | − | − | − |

| CDKN2A | − | − | − |

| CTNNB1 | − | − | |

| EGFR | − | − | − |

| FGFR1/2/3 | − | − | − |

| HF3A | − | − | − |

| HIST1H3B | − | − | − |

| MET | − | − | |

| PDGFRA | Variant | − | Pathologic mutation |

| PTEN | − | − | |

| PTPN11 | − | − | |

| TERT | − | − | − |

| GNA11 | Variant | ||

| PPM1D | Variant | ||

| MGMT promoter methylation | + | − | + |

| Gene fusion events | − | − | − |

| Chromosomal microarray | Near-haploid/pseudohyperdiploid genome with gain of chromosome 7 and copy neutral loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 10. | Chromosome copy number complexity with chromothripsis of chromosome 2, loss of 7p22.3p21.3, loss of 9p, loss of 11p, loss of chromosome 12, loss of 13q11q12.11, loss of 13q14.11q14.3 (including RB1), loss of 13q21.31q21.32, loss of 14q12q32.33, loss of 17p13.3p11.2 (including TP53), multiple level gain of 17q, and loss of 19q13.43. | Loss of chromosomes 2 and 5, loss of 9p24.3p21.1 (including CDKN2A and CDKN2B), and gain of chromosome 17. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milani, M.N.; Chen, C.P.; Sloan, L.; Neil, E.C.; Yekula, A.; Fitzpatrick, G.; Chen, L. Limitations of DNA Methylation Profiling in High-Grade Gliomas: Case Series. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3225. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243225

Milani MN, Chen CP, Sloan L, Neil EC, Yekula A, Fitzpatrick G, Chen L. Limitations of DNA Methylation Profiling in High-Grade Gliomas: Case Series. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3225. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243225

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilani, Marcus N., Constance P. Chen, Lindsey Sloan, Elizabeth C. Neil, Aundeep Yekula, Garret Fitzpatrick, and Liam Chen. 2025. "Limitations of DNA Methylation Profiling in High-Grade Gliomas: Case Series" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3225. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243225

APA StyleMilani, M. N., Chen, C. P., Sloan, L., Neil, E. C., Yekula, A., Fitzpatrick, G., & Chen, L. (2025). Limitations of DNA Methylation Profiling in High-Grade Gliomas: Case Series. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3225. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243225