Morphological Changes in the Placenta of Patients with COVID-19 During Pregnancy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Groups

2.2. Histological Examination

2.3. Immunohistochemical Study

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Groups

3.2. Histological Findings

3.2.1. Inflammatory Alterations

3.2.2. The Influence of Clinical Manifestations of COVID-19 on the Severity of Morphological Changes in the Placenta

3.2.3. Analysis of the Influence of Clinical Manifestations of COVID-19 on the Severity of Fetal Vascular Lesions

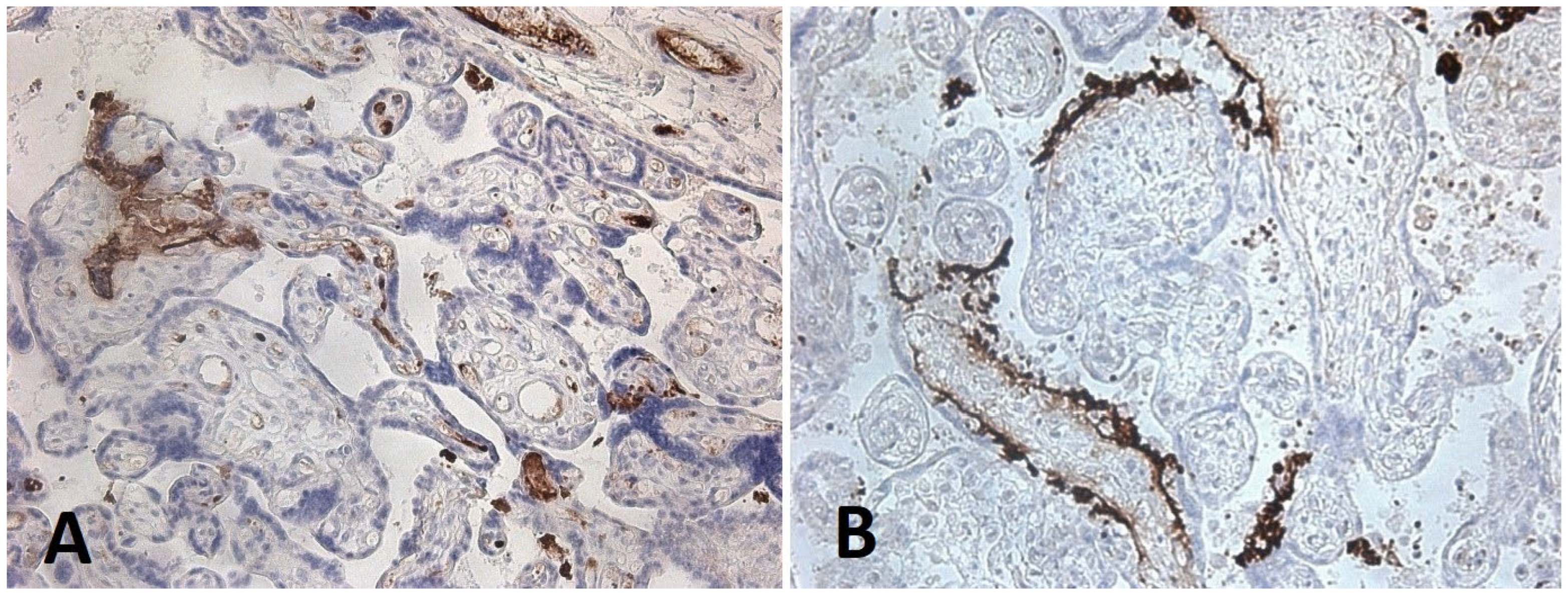

3.3. Immunohistochemical Analysis of Placental Tissue

- -

- in the endothelium of villous vessels, detected in five cases, with expression in 50% of endothelial cells in one case;

- -

- in villous macrophages, expression was found in 1% of cells in six cases, 10% in one case, 50% in two cases, and 100% in one case;

- -

- in villous fibroblasts, expression was identified in 30% and 100% of cells in two cases;

- -

- in fibroblasts of the chorionic plate and amnion, expression was present in 50% of cells in two cases and in 100% of cells in another two cases.

4. Discussion

5. Practical Implications

6. Study Limitation

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karimi, L.; Makvandi, S.; Vahedian-Azimi, A.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effect of COVID-19 on Mortality of Pregnant and Postpartum Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pregnancy 2021, 2021, 8870129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewska, B.; Barratt, I.; Townsend, R.; Kalafat, E.; van der Meulen, J.; Gurol-Urganci, I.; O’Brien, P.; Morris, E.; Draycott, T.; Thangaratinam, S.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e759–e772, Correction in Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, J.; Ariff, S.; Gunier, R.B.; Thiruvengadam, R.; Rauch, S.; Kholin, A.; Roggero, P.; Prefumo, F.; Vale, M.S.D.; Cardona-Perez, J.A.; et al. Maternal and Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality Among Pregnant Women with and Without COVID-19 Infection: The INTERCOVID Multinational Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 817–826, Correction in JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Sun, W.; Yang, S.; Liu, T.; Hou, N. The impact of COVID-19 infections on pregnancy outcomes in women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.Q.; Bilodeau-Bertrand, M.; Liu, S.; Auger, N. The impact of COVID-19 on pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2021, 193, E540–E548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.D.; Zhu, L.J.; Yin, J.; Wen, J. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 2022, 213, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, G.; Mappa, I.; Maqina, P.; Bitsadze, V.; Khizroeva, J.; Makatsarya, A.; D’aNtonio, F. Effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the second half of pregnancy on fetal growth and hemodynamics: A prospective study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2021, 100, 1034–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magawa, S.; Nii, M.; Enomoto, N.; Tamaishi, Y.; Takakura, S.; Maki, S.; Ishida, M.; Osato, K.; Kondo, E.; Sakuma, H.; et al. COVID-19 during pregnancy could potentially affect placental function. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023, 36, 2265021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.R.; Oakley, E.; Grandner, G.W.; Ferguson, K.; Farooq, F.; Afshar, Y.; Ahlberg, M.; Ahmadzia, H.; Akelo, V.; Aldrovandi, G.; et al. Adverse maternal, fetal, and newborn outcomes among pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection: An individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e009495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorghiou, A.T.; Deruelle, P.; Gunier, R.B.; Rauch, S.; García-May, P.K.; Mhatre, M.; Usman, M.A.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Etuk, S.; Simmons, L.E.; et al. Preeclampsia and COVID-19: Results from the INTERCOVID prospective longitudinal study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 289.e1–289.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Agudelo, A.; Romero, R. SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 68–89.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motwani, R.; Deshmukh, V.; Kumar, A.; Kumari, C.; Raza, K.; Krishna, H. Pathological involvement of placenta in COVID-19: A systematic review. Infez. Med. 2022, 30, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharps, M.C.; Hayes, D.J.L.; Lee, S.; Zou, Z.; Brady, C.A.; Almoghrabi, Y.; Kerby, A.; Tamber, K.K.; Jones, C.J.; Waldorf, K.M.A.; et al. A structured review of placental morphology and histopathological lesions associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Placenta 2020, 101, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patberg, E.T.; Adams, T.; Rekawek, P.; Vahanian, S.A.; Akerman, M.; Hernandez, A.; Rapkiewicz, A.V.; Ragolia, L.; Sicuranza, G.; Chavez, M.R.; et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection and placental histopathology in women delivering at term. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 224, 382.e1–382.e18, Correction in Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Girolamo, R.; Khalil, A.; Alameddine, S.; D’ANgelo, E.; Galliani, C.; Matarrelli, B.; Buca, D.; Liberati, M.; Rizzo, G.; D’ANtonio, F. Placental histopathology after SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2021, 3, 100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Avvad-Portari, E.; Babál, P.; Baldewijns, M.; Blomberg, M.; Bouachba, A.; Camacho, J.; Collardeau-Frachon, S.; Colson, A.; Dehaene, I.; et al. Placental Tissue Destruction and Insufficiency From COVID-19 Causes Stillbirth and Neonatal Death From Hypoxic-Ischemic Injury. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2022, 146, 660–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Mulkey, S.B.; Roberts, D.J. SARS-CoV-2 placentitis, stillbirth, and maternal COVID-19 vaccination: Clinical-pathologic correlations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhren, J.T.; Meinardus, A.; Hussein, K.; Schaumann, N. Meta-analysis on COVID-19-pregnancy-related placental pathologies shows no specific pattern. Placenta 2022, 117, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbetta-Rastelli, C.M.; Altendahl, M.; Gasper, C.; Goldstein, J.D.; Afshar, Y.; Gaw, S.L. Analysis of placental pathology after COVID-19 by timing and severity of infection. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baergen, R.N.; Heller, D.S. Placental Pathology in COVID-19 Positive Mothers: Preliminary Findings. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2020, 23, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Agarwal, R.; Yadav, D.; Singh, S.; Kumar, H.; Bhardwaj, R. Histopathological Changes in Placenta of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection and Maternal and Perinatal Outcome in COVID-19. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 2023, 73, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Ren, J.; Xu, L.; Ke, X.; Xiong, L.; Tian, X.; Fan, C.; Yan, H.; Yuan, J. Placental pathology of the third trimester pregnant women from COVID-19. Diagn. Pathol. 2021, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesaka, S.R.; Obimbo, M.M.; Wanyoro, A. Coronavirus disease 2019 and the placenta: A literature review. Placenta 2022, 126, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, J.; Casanello, P.; Toso, A.; Farías, M.; Carrasco-Negue, K.; Araujo, K.; Valero, P.; Fuenzalida, J.; Solari, C.; Sobrevia, L. Functional consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women, fetoplacental unit, and neonate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2023, 1869, 166582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey-Collier, K.; Craig, A.M.; Hall, A.; Weaver, K.E.; Wheeler, S.M.; Gilner, J.B.; Swamy, G.K.; Hughes, B.L.; Dotters-Katz, S.K. Symptomatic versus asymptomatic COVID-19: Does it impact placental vasculopathy? J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 9460–9462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Mascio, D.; Khalil, A.; Saccone, G.; Rizzo, G.; Buca, D.; Liberati, M.; Vecchiet, J.; Nappi, L.; Scambia, G.; Berghella, V.; et al. Outcome of coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID-19) during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2020, 2, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.G.; Toner, L.E.; Stone, J.; Iwelumo, C.A.; Goldberger, C.; Roser, B.J.; Shah, R.; Rattner, P.; Paul, K.S.; Stoffels, G.; et al. Pregnancy During a Pandemic: A Cohort Study Comparing Adverse Outcomes During and Before the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Perinatol. 2023, 40, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachnas, M.A.; Putri, A.O.; Rahmi, E.; Pranabakti, R.A.; Anggraini, N.W.P.; Astetri, L.; Yuliantara, E.E.; Prabowo, W.; Respati, S.H. Placental damage comparison between preeclampsia with COVID-19, COVID-19, and preeclampsia: Analysis of caspase-3, caspase-1, and TNF-alpha expression. AJOG Glob. Rep. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Pliego, A.; Miranda, J.; Vega-Torreblanca, S.; Valdespino-Vázquez, Y.; Helguera-Repetto, C.; Espejel-Nuñez, A.; Borboa-Olivares, H.; Sosa, S.E.Y.; Mateu-Rogell, P.; León-Juárez, M.; et al. Molecular Insights into the Thrombotic and Microvascular Injury in Placental Endothelium of Women with Mild or Severe COVID-19. Cells 2021, 10, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.A.; Roman, A.S.; Limaye, M.; Grossman, T.B.; Flaifel, A.; Vaz, M.J.; Thomas, K.M.; Penfield, C.A. Association of SARS-CoV-2 placental histopathology findings with maternal-fetal comorbidities and severity of COVID-19 hypoxia. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 35, 8412–8418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaumann, N.; Suhren, J.T. An Update on COVID-19-Associated Placental Pathologies. Ein Update zu COVID-19-assoziierten Pathologien in der Plazenta. Z. Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2024, 228, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manasova, G.S.; Stasy, Y.A.; Kaminsky, V.V.; Gladchuk, I.Z.; Nitochko, E.A. Histological and immunohistochemical features of the placenta associated with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Wiad. Lek. 2024, 77, 1434–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosto, V.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Alqasem, M.; Tsibizova, V.; Di Renzo, G.C. SARS-CoV-2 Footprints in the Placenta: What We Know after Three Years of the Pandemic. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayad, B.; Mohseni Afshar, Z.; Mansouri, F.; Salimi, M.; Miladi, R.; Rahimi, S.; Rahimi, Z.; Shirvani, M. Pregnancy, Preeclampsia, and COVID-19: Susceptibility and Mechanisms: A Review Study. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2022, 16, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinis, C.; Toffoli, M.; Spazzapan, M.; Balduit, A.; Zito, G.; Mangogna, A.; Zupin, L.; Salviato, T.; Maiocchi, S.; Romano, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 modulates virus receptor expression in placenta and can induce trophoblast fusion, inflammation and endothelial permeability. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 957224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radan, A.P.; Renz, P.; Raio, L.; Villiger, A.-S.; Haesler, V.; Trippel, M.; Surbek, D. SARS-CoV-2 replicates in the placenta after maternal infection during pregnancy. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1439181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreis, N.N.; Ritter, A.; Louwen, F.; Yuan, J. A Message from the Human Placenta: Structural and Immunomodulatory Defense against SARS-CoV-2. Cells 2020, 9, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashary, N.; Bhide, A.; Chakraborty, P.; Colaco, S.; Mishra, A.; Chhabria, K.; Jolly, M.K.; Modi, D. Single-Cell RNA-seq Identifies Cell Subsets in Human Placenta That Highly Expresses Factors Driving Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celewicz, A.; Celewicz, M.; Michalczyk, M.; Woźniakowska-Gondek, P.; Krejczy, K.; Misiek, M.; Rzepka, R. SARS CoV-2 infection as a risk factor of preeclampsia and pre-term birth. An interplay between viral infection, pregnancy-specific immune shift and endothelial dysfunction may lead to negative pregnancy outcomes. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2197289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ding, C.; Poon, L.C.; Wang, H.; Yang, H. Single-cell RNA expression profiling of SARS-CoV-2-related ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in human trophectoderm and placenta. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nádasdi, Á.; Sinkovits, G.; Bobek, I.; Lakatos, B.; Förhécz, Z.; Prohászka, Z.Z.; Réti, M.; Arató, M.; Cseh, G.; Masszi, T.; et al. Decreased circulating dipeptidyl peptidase-4 enzyme activity is prognostic for severe outcomes in COVID-19 inpatients. Biomark. Med. 2022, 16, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas-Sánchez, R.; Sánchez-Muñoz, F.; Guzmán-Martín, C.A.; Couder, A.H.-D.; Rojas-Velasco, G.; Fragoso, J.M.; Vargas-Alarcón, G. Dipeptidylpeptidase-4 levels and DPP4 gene polymorphisms in patients with COVID-19. Association with disease and with severity. Life Sci. 2021, 276, 119410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonacker, E.; Wierenga, E.; Smits, H.; Van Noorden, C. CD26/DPPIV signal transduction function, but not proteolytic activity, is directly related to its expression level on human Th1 and Th2 cell lines as detected with living cell cytochemistry. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2002, 50, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Nie, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Deng, L.; Song, S.; Ma, Z.; Mo, P.; Zhang, Y. Characteristics of peripheral lymphocyte subset alteration in COVID-19 pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrofanova, L.B.; Makarov, I.A.; Gorshkov, A.N.; Runov, A.L.; Vonsky, M.S.; Pisareva, M.M.; Komissarov, A.B.; Makarova, T.A.; Li, Q.; Karonova, T.L.; et al. Comparative Study of the Myocardium of Patients from Four COVID-19 Waves. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchegolev, A.I.; Kulikova, G.V.; Lyapin, V.M.; Shmakov, R.G.; Sukhikh, G.T. The Number of Syncytial Knots and VEGF Expression in Placental Villi in Parturient Woman with COVID-19 Depends on the Disease Severity. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 171, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, I.; Limonta, D.; Mahal, L.K.; Hobman, T.C. Endothelium Infection and Dysregulation by SARS-CoV-2: Evidence and Caveats in COVID-19. Viruses 2020, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrofanova, L.; Makarov, I.; Gorshkov, A.; Vorobeva, O.; Simonenko, M.; Starshinova, A.; Kudlay, D.; Karonova, T. New Scenarios in Heart Transplantation and Persistency of SARS-CoV-2 (Case Report). Life 2023, 13, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussani, R.; Zentilin, L.; Correa, R.; Colliva, A.; Silvestri, F.; Zacchigna, S.; Collesi, C.; Giacca, M. Persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients seemingly recovered from COVID-19. J. Pathol. 2023, 259, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, A.A.; Tikhonova, E.; Kudryavtsev, I.; Kudlay, D.; Korsunsky, I.; Beleniuk, V.; Borisov, A. TREC/KREC Levels and T and B Lymphocyte Subpopulations in COVID-19 Patients at Different Stages of the Disease. Viruses 2022, 14, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kudlay, D.; Kofiadi, I.; Khaitov, M. Peculiarities of the T Cell Immune Response in COVID-19. Vaccines 2022, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gudima, G.; Kofiadi, I.; Shilovskiy, I.; Kudlay, D.; Khaitov, M. Antiviral Therapy of COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Taş, F.; Erdemci, F.; Aşır, F.; Maraşlı, M.; Deveci, E. Histopathological examination of the placenta after delivery in pregnant women with COVID-19. J. Health Sci. Med. 2022, 5, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Group 1 (COVID-19 and Preeclampsia (2022), n = 20) | Group 2 (COVID-19 without Preeclampsia (2022), n = 20) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Trimester of COVID-19 infection | ||||

| 1st trimester | 7 | 35.0 | 6 | 30.0 |

| 2nd trimester | 10 | 50.0 | 12 | 60.0 |

| 3rd trimester | 3 | 15.0 | 2 | 10.0 |

| Severity of COVID-19 | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 10 | 50.0 | 10 | 50.0 |

| Mild | 8 | 40.0 | 9 | 45.0 |

| Moderate | 2 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.0 |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pathological Feature | Group 1 (2022): COVID-19 + PE (n = 20) | Group 2 (2022): COVID-19 Without PE (n = 20) | Group 3 (2019): PE Without COVID-19 (n = 5) | Group 4 (2019): No Gestational Complications/COVID-19 (n = 5) | p-Value (Fisher’s Exact Test) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Villous maturation discordant with gestational age | 4 | 20.0 | 1 | 5.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.128 |

| Delayed villous maturation | 4 | 20.0 | 2 | 10.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.651 |

| Dissociated villous maturation | 5 | 25.0 | 3 | 15.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.796 |

| Distal villous hypoplasia | 4 | 20.0 | 2 | 10.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.651 |

| Accelerated villous maturation and increased syncytial knots | 18 | 90.0 | 10 | 50.0 | 4 | 80.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 0.023 * p1–2 = 0.035 * |

| Excessive fibrinoid deposition in the intervillous space | 13 | 65.0 | 6 | 30.0 | 5 | 100.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0.006 * p1–2 = 0.027 *; p2–3 = 0.048 * |

| Extensive pseudo-infarctions | 20 | 100.0 | 8 | 40.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 0 | 0 | <0.0001 * p1–2 = 0.006 *; p1–3 = 0.048 * |

| Placental infarctions | 5 | 25.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.176 |

| —Recent | 4 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| —Old | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Intervillous hematomas | 6 | 30.0 | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.090 |

| Retroplacental hematomas | 1 | 5.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Intervillous space narrowing due to hypervillous transformation | 4 | 20.0 | 8 | 40.0 | 3 | 60.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.106 |

| Remodeling of chorionic plate and main stem arteries | 11 | 55.0 | 6 | 30.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.099 |

| Pathological Feature | Group 1 (2022): COVID-19 + PE (n = 20) | Group 2 (2022): COVID-19 Without PE (n = 20) | Group 3 (2019): PE Without COVID-19 (n = 5) | Group 4 (2019): No Gestational Complications/COVID-19 (n = 5) | p-Value (Fisher’s Exact Test) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Chorangiosis (≥10 villi with ≥10 vessels each) | 14 | 70.0 | 5 | 25.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 0.026 * p1–2 = 0.024 |

| Complexes of avascular villi | 8 | 40.0 | 2 | 10.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.079 |

| Distorted vascularization of terminal villi | 6 | 30.0 | 2 | 10.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.287 |

| Thrombosis of subchorionic space | 4 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.130 |

| Karyolysis of vascular wall and villous stromal cells with villous chorion fibrosis | 15 | 75.0 | 3 | 15.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 1 | 20.0 | <0.002 * p1–2 = <0.002 *; p1–4 = 0.024 * |

| Vascularization of stem villi | 11 | 55.0 | 4 | 20.0 | 3 | 60.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.023 * p1–2 = 0.022 * |

| Ectasia of villous vessels | 6 | 30.0 | 6 | 30.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 2 | 40.0 | 1.000 |

| Umbilical vessel abnormalities (dilatation, mural or occlusive thrombosis) | 2 | 10.0 | 2 | 10.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.796 |

| Pathological Changes | Group 1 (2022): COVID-19 and PE (n = 20) | Group 2 (2022): COVID-19 Without PE (n = 20) | Group 3 (2019): PE Without COVID-19 (n = 5) | Group 4 (2019): Without Gestational Complications and COVID-19 (n = 5) | p Value (Fisher’s Exact Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signs of intra-amniotic infection | 7 (35.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0.376 |

| Purulent chorio-deciduitis | 8 (40.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0.027 * p1–2 = 0.028 |

| Signs of hematogenous infection and chronic inflammatory response | |||||

| Productive basal deciduitis | 13 (65.0%) | 8 (40.0%) | 4 (80.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0.306 |

| Productive chorio-deciduitis | 9 (45.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.001 * p1–2 = 0.006 |

| Villitis | 8 (40.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.019 * p1–2 = 0.023; p2–3 = 0.023 |

| Intervillositis | 1 (5.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0.363 |

| Pathological Changes | Asymptomatic COVID-19 (2022), n = 10 | Asymptomatic COVID-19 and PE (2022), n = 10 | Symptomatic COVID-19 (2022), n = 10 | Symptomatic COVID-19 and PE (2022), n = 10 | p Value (Fisher’s Exact Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discrepancy between villous chorion maturity and gestational age | 0 (0%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (20%) | 0.726 |

| Delayed villous chorion maturation | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (20%) | 4 (40%) | 0.038 * |

| Dissociated villous chorion maturation | 0 (0%) | 4 (40%) | 3 (30%) | 1 (10%) | 0.140 |

| Distal villous hypoplasia | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (30%) | 0.463 |

| Accelerated villous chorion maturation and increased syncytial knots | 3 (30%) | 9 (90%) | 7 (70%) | 9 (90%) | 0.010 * (p1–2, p1–4 = 0.01) |

| Excessive fibrinoid deposition in the intervillous space | 2 (20%) | 5 (50%) | 4 (40%) | 8 (80%) | 0.073 |

| Extensive pseudo-infarctions | 1 (10%) | 10 (100%) | 7 (70%) | 10 (100%) | <0.0001 * (p1–2, p1–4 =0.0006; p1–3 = 0.0001) |

| Placental infarctions—recent—old | 0 (0%) | 3 (30%)/2 (20%)/1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (30%)/2 (20%)/1 (10%) | 0.226 |

| Intervillous hematomas | 1 (10%) | 5 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) | 0.041 ** |

| Retroplacental hematomas | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Narrowing of the intervillous space due to hypervillosis | 3 (30%) | 3 (30%) | 5 (50%) | 1 (10%) | 0.329 |

| Remodeling of the chorionic plate and major arterial vessels | 0 (0%) | 6 (60%) | 6 (60%) | 5 (50%) | 0.010 * (p1–2, p1–3 = 0.03) |

| Pathological Changes | Asymptomatic COVID-19 (2022), n = 10 | Asymptomatic COVID-19 and PE (2022), n = 10 | Symptomatic COVID-19 (2022), n = 10 | Symptomatic COVID-19 and PE (2022), n = 10 | p Value (Fisher’s Exact Test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chorangiosis (10 villi with 10 vessels) | 1 (10.0%) | 7 (70.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 7 (70.0%) | 0.022 (p1–2, p1–4 = 0.019) |

| Complexes of avascular villi | 0 (0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 0.017 * (p1–4 = 0.036) |

| Distorted vascularization of terminal villi | 0 (0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 0.207 |

| Thrombosis of the subchorionic space | 0 (0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0.300 |

| Karyolysis of vascular wall and stromal cells, villous chorion fibrosis | 1 (10.0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 9 (90.0%) | 0.001 * (p1–4, p1–2, p3–4 = 0.001) |

| Vascularization of stem villi | 0 (0%) | 6 (60.0%) | 4 (40.0%) | 5 (50.0%) | 0.023 * (p1–2 = 0.048) |

| Ectasia of villous vessels | 4 (40.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 5 (50.0%) | 0.252 |

| Umbilical cord vessels: ectasia, mural thrombi, occlusive thrombi | 0 (0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.300 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rudenko, K.; Roshchina, T.; Zazerskaya, I.; Kudlay, D.; Starshinova, A.; Mitrofanova, L. Morphological Changes in the Placenta of Patients with COVID-19 During Pregnancy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3188. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243188

Rudenko K, Roshchina T, Zazerskaya I, Kudlay D, Starshinova A, Mitrofanova L. Morphological Changes in the Placenta of Patients with COVID-19 During Pregnancy. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3188. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243188

Chicago/Turabian StyleRudenko, Kseniia, Tatiana Roshchina, Irina Zazerskaya, Dmitry Kudlay, Anna Starshinova, and Lubov Mitrofanova. 2025. "Morphological Changes in the Placenta of Patients with COVID-19 During Pregnancy" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3188. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243188

APA StyleRudenko, K., Roshchina, T., Zazerskaya, I., Kudlay, D., Starshinova, A., & Mitrofanova, L. (2025). Morphological Changes in the Placenta of Patients with COVID-19 During Pregnancy. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3188. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243188