High-Resolution Nerve Ultrasound in Adults with NF1: An Accessible and Reproducible Imaging Tool for Plexiform Neurofibromas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Clinical Examination

2.3. Nerve Conduction Studies

2.4. High-Resolution Nerve Ultrasound

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Symptoms and Interventions

3.2. NCS

3.3. HRUS Pattern

3.4. HRUS CSA Measurements

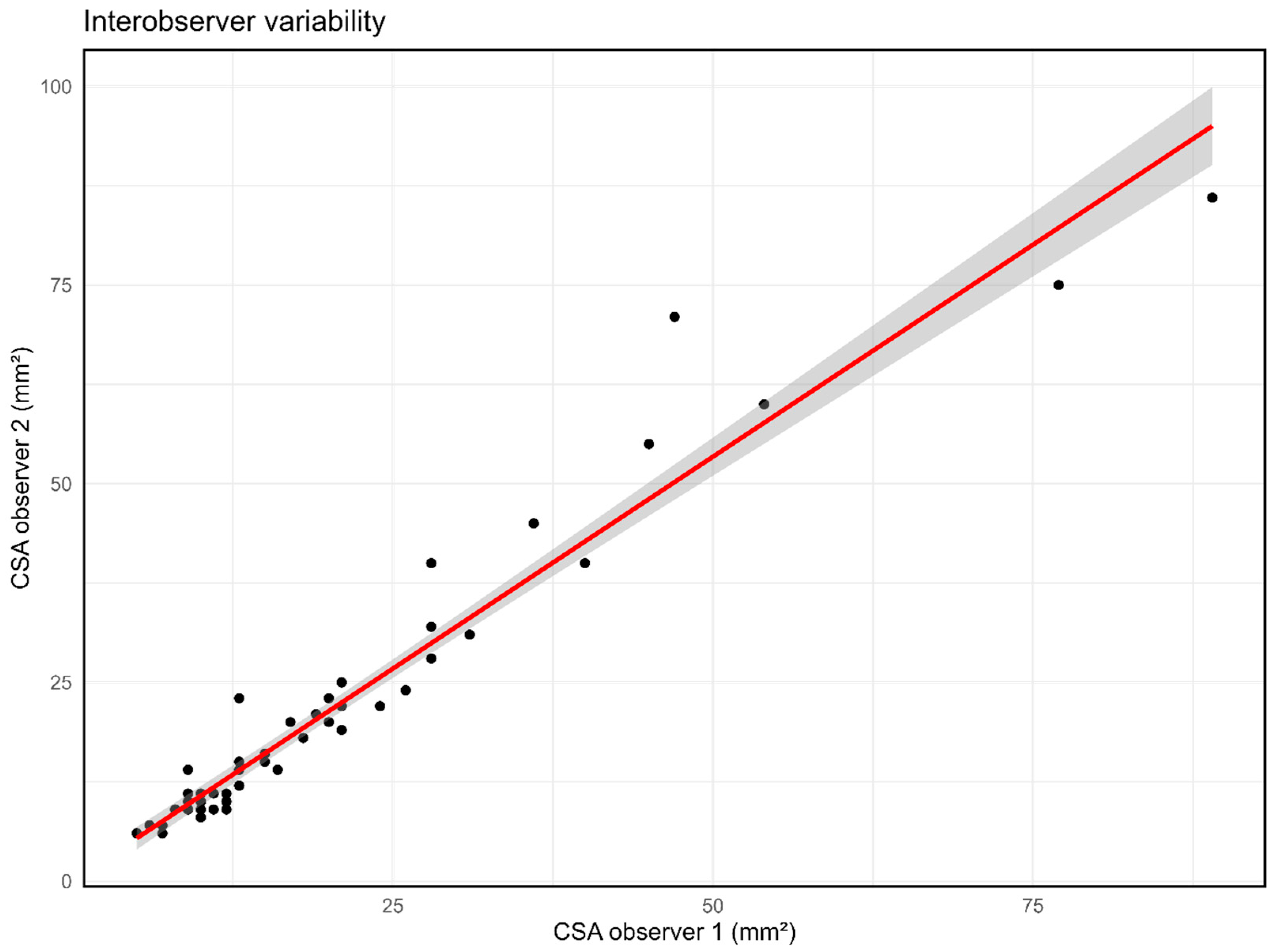

3.5. Interobserver Variability of HRUS in NF1

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ejerskov, C.; Farholt, S.; Nielsen, F.S.K.; Berg, I.; Thomasen, S.B.; Udupi, A.; Agesen, T.; de Fine Licht, S.; Handrup, M.M. Clinical Characteristics and Management of Children and Adults with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and Plexiform Neurofibromas in Denmark: A Nationwide Study. Oncol. Ther. 2022, 11, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucker, T.; Wolkenstein, P.; Revuz, J.; Zeller, J.; Friedman, J.M. Association between benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in NF1. Neurology 2005, 65, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolberg, M.; Holand, M.; Agesen, T.H.; Brekke, H.R.; Liestol, K.; Hall, K.S.; Mertens, F.; Picci, P.; Smeland, S.; Lothe, R.A. Survival meta-analyses for >1800 malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor patients with and without neurofibromatosis type 1. Neuro Oncol. 2013, 15, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Tang, X.; Liang, H.; Yang, R.; Yan, T.; Guo, W. Prognosis and risk factors for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 18, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.R.; Puj, K.S.; Salunke, A.A.; Pandya, S.J.; Gandhi, J.S.; Parikh, A.R. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor with analysis of various prognostic factors: A single-institutional experience. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2021, 17, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carton, C.; Evans, D.G.; Blanco, I.; Friedrich, R.E.; Ferner, R.E.; Farschtschi, S.; Salvador, H.; Azizi, A.A.; Mautner, V.; Rohl, C.; et al. ERN GENTURIS tumour surveillance guidelines for individuals with neurofibromatosis type 1. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 56, 101818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telleman, J.A.; Stellingwerff, M.D.; Brekelmans, G.J.; Visser, L.H. Nerve ultrasound in neurofibromatosis type 1: A follow-up study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2018, 129, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlister, S.; McGain, F.; Petersen, M.; Story, D.; Charlesworth, K.; Ison, G.; Barratt, A. The carbon footprint of hospital diagnostic imaging in Australia. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2022, 24, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noordhoek, D.C.; Ennik, T.A.; van Dijk, S.A.; Mann, E.; van der Vlist, S.; Drenthen, J.; Taal, W. High resolution nerve ultrasound in neurofibromatosis type 1: A prospective and descriptive study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2025, 179, 2110992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, R.; Jett, K.; Harris, G.J.; Cai, W.; Friedman, J.M.; Mautner, V.F. Benign whole body tumor volume is a risk factor for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis type 1. J. Neurooncol. 2014, 116, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, K.I.; Merker, V.L.; Cai, W.; Bredella, M.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Thalheimer, R.D.; Da, J.L.; Orr, C.C.; Herr, H.P.; Morris, M.E.; et al. Ten-Year Follow-up of Internal Neurofibroma Growth Behavior in Adult Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Using Whole-Body MRI. Neurology 2023, 100, e661–e670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medical Research Council. Aids to Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System; Volume Memorandum, No. 45; Her Majesty’s Stationary Office: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Buschbacher, R.M.; Prahlow, P.N. Manual of Nerve Conduction Studies, 2nd ed.; Demos Medical Publishing: New York City, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Goedee, H.S.; van der Pol, W.L.; van Asseldonk, J.H.; Franssen, H.; Notermans, N.C.; Vrancken, A.J.; van Es, M.A.; Nikolakopoulos, S.; Visser, L.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Diagnostic value of sonography in treatment-naive chronic inflammatory neuropathies. Neurology 2017, 88, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, D.W.; An, J.Y. Cross-sectional area reference values for high-resolution ultrasonography of the upper extremity nerves in healthy Asian adults. Medicine 2021, 100, e25812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, R.; Dombi, E.; Widemann, B.C.; Solomon, J.; Fuensterer, C.; Kluwe, L.; Friedman, J.M.; Mautner, V.F. Growth dynamics of plexiform neurofibromas: A retrospective cohort study of 201 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2012, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akshintala, S.; Baldwin, A.; Liewehr, D.J.; Goodwin, A.; Blakeley, J.O.; Gross, A.M.; Steinberg, S.M.; Dombi, E.; Widemann, B.C. Longitudinal evaluation of peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis type 1: Growth analysis of plexiform neurofibromas and distinct nodular lesions. Neuro-Oncology 2020, 22, 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telleman, J.A. Nerve ultrasound: A reproducible diagnostic tool in peripheral neuropathy. Neurology 2019, 92, e443–e450. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm, J. High-resolution ultrasonography of peripheral nerves: Measurements on 14 nerve segments in 56 healthy subjects and reliability assessments. Ultraschall. Med. 2014, 35, 459–467. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliafico, A. Reliability of side-to-side ultrasound cross-sectional area measurements of lower extremity nerves in healthy subjects. Muscle Nerve 2012, 46, 717–722. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliafico, A.; Martinoli, C. Reliability of side-to-side sonographic cross-sectional area measurements of upper extremity nerves in healthy volunteers. J. Ultrasound Med. 2013, 32, 457–462. [Google Scholar]

- Herraets, I.J.T.; Goedee, H.S.; Telleman, J.A.; van Eijk, R.P.A.; Verhamme, C.; Saris, C.G.J.; Eftimov, F.; van Alfen, N.; van Asseldonk, J.T.; Visser, L.H.; et al. Nerve ultrasound for diagnosing chronic inflammatory neuropathy: A multicenter validation study. Neurology 2020, 95, e1745–e1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Baseline | Follow-Up | |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex—no. (%) | 40 (77) | |

| Median age—years (range) | 44 (18–72) | |

| Median follow-up time—months (range) | 26 (22–40) | |

| PNS-related symptoms—no. (%) | 30 (58) | 23 (44) |

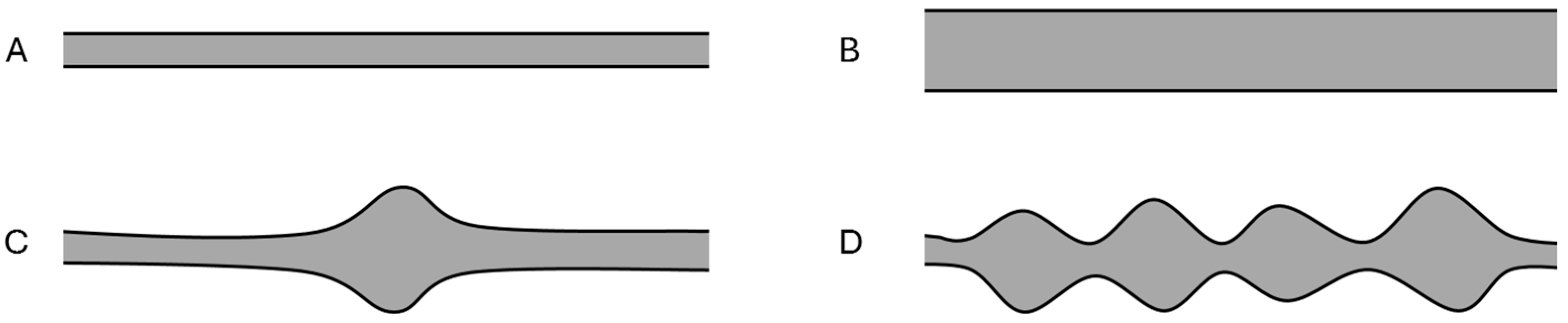

| HRUS pattern | ||

| Normal—no. (%) | 7 (13) | 7 (13) |

| Nerve enlargement(s) with normal nerve morphology—no. (%) | 13 (25) | 13 (25) |

| Focal PNs—no. (%) | 9 (17) | 9 (17) |

| Continuous PNs—no. (%) | 23 (44) | 23 (44) |

| Abnormal NCSs—no. (%) | 17 (33) | 13 (25) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noordhoek, D.C.; van Tulder, K.C.; Ennik, T.A.; Taal, W.; Drenthen, J. High-Resolution Nerve Ultrasound in Adults with NF1: An Accessible and Reproducible Imaging Tool for Plexiform Neurofibromas. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243146

Noordhoek DC, van Tulder KC, Ennik TA, Taal W, Drenthen J. High-Resolution Nerve Ultrasound in Adults with NF1: An Accessible and Reproducible Imaging Tool for Plexiform Neurofibromas. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243146

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoordhoek, D. Christine, Koen C. van Tulder, Tessa A. Ennik, Walter Taal, and Judith Drenthen. 2025. "High-Resolution Nerve Ultrasound in Adults with NF1: An Accessible and Reproducible Imaging Tool for Plexiform Neurofibromas" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243146

APA StyleNoordhoek, D. C., van Tulder, K. C., Ennik, T. A., Taal, W., & Drenthen, J. (2025). High-Resolution Nerve Ultrasound in Adults with NF1: An Accessible and Reproducible Imaging Tool for Plexiform Neurofibromas. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3146. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243146