A Machine-Learning-Based Clinical Decision Model for Predicting Amputation Risk in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Diagnostic Performance and Practical Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Subjects

- (a)

- Admitted to hospital with a diagnosis that met DFU’s clinical diagnostic criteria;

- (b)

- Diabetic foot patients above Wagner level 1;

- (c)

- Routine laboratory tests and auxiliary examinations have been completed after admission;

- (d)

- Surgical treatment has been performed during the visit;

- (e)

- The number of hospitalizations of the patient within the investigation range ≤2 times;

- (f)

- This study protocol was known to the patient, and the patient himself was informed and consented.

- (a)

- Patients with other infectious diseases;

- (b)

- Patients with malignant tumors;

- (c)

- Patients younger than 18 years;

- (d)

- Patients transferred to other healthcare facilities during treatment.

2.2. Subject Inclusion Index

2.3. Data Preprocessing

2.4. Statistical Analyses

2.5. Model Development

2.6. Model Assessment and Validation

2.7. Flowchart of the Study Design and Model Construction

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Test Result

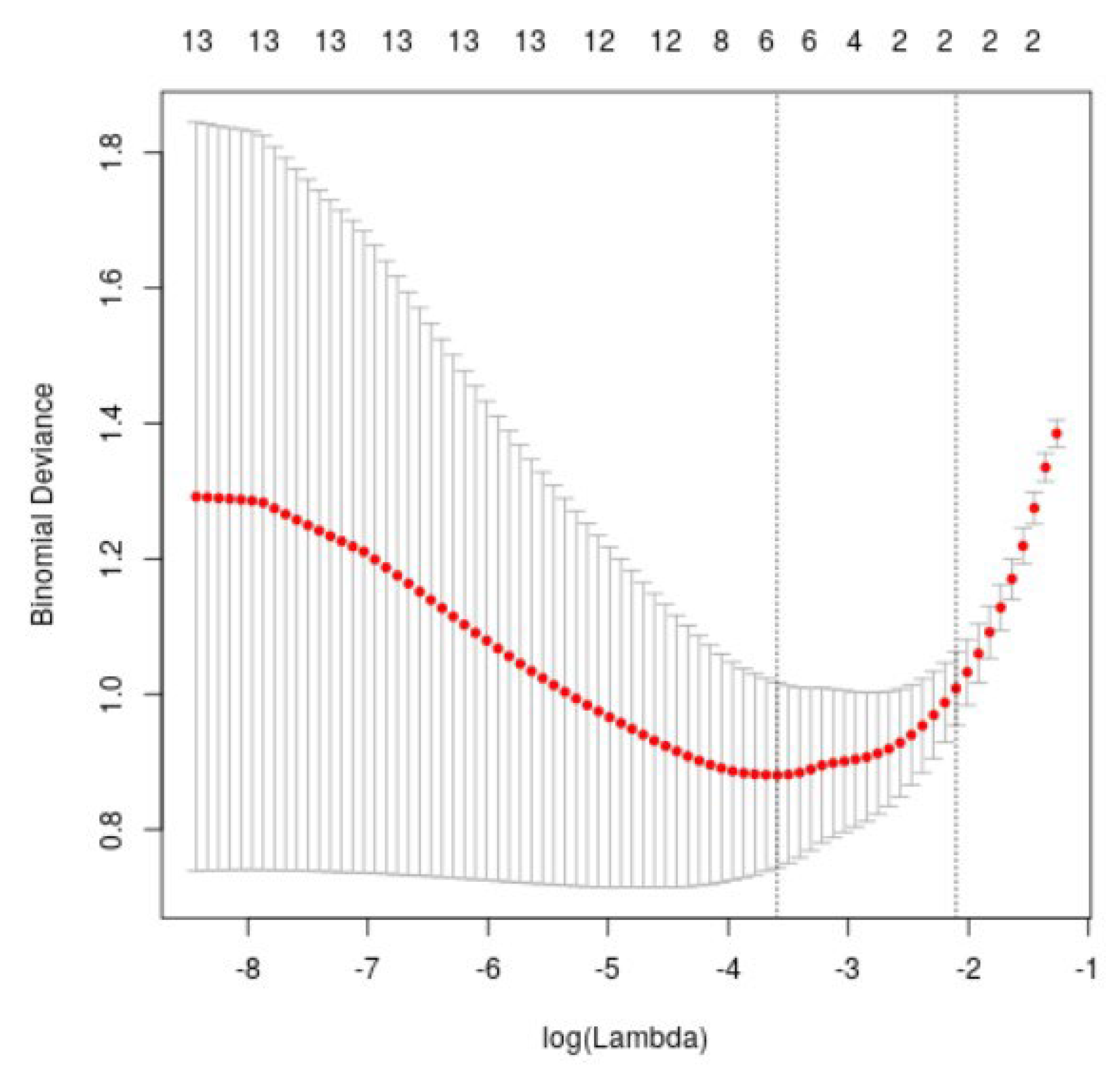

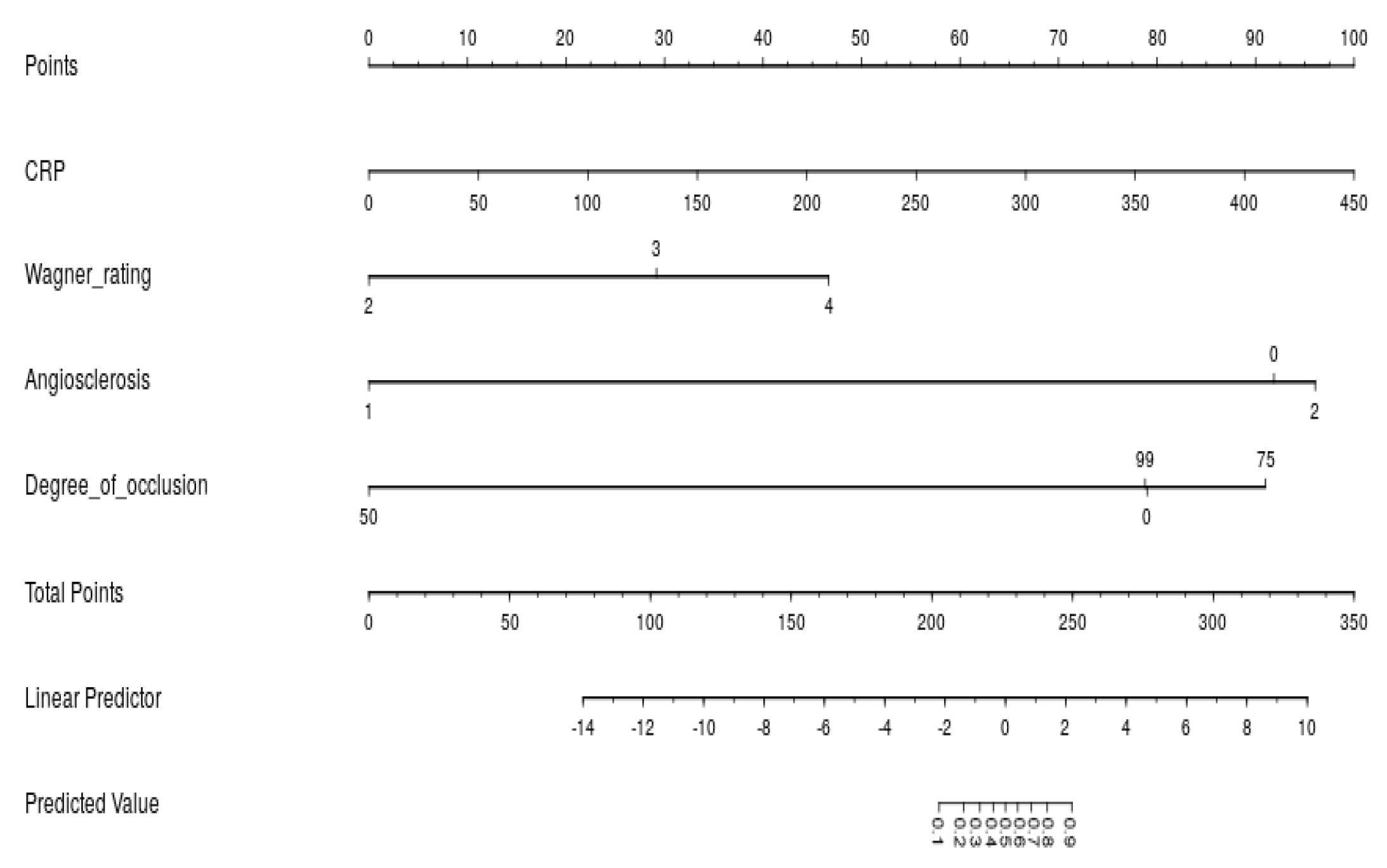

3.2. Determine Input Variable

3.3. Model Performance

3.4. Model Evaluation

3.5. Multimodal Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, B.; Eisenberg, N.; Beaton, D.; Lee, D.S.; Al-Omran, L.; Wijeysundera, D.N.; Hussain, M.A.; Rotstein, O.D.; de Mestral, C.; Mamdani, M.; et al. Predicting mortality risk following major lower extremity amputation using machine learning. J. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 82, 617–631.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.A.; Hamilton, E.J.; Russell, D.A.; Game, F.; Wang, S.C.; Baptista, S.; Monteiro-Soares, M. Diabetic Foot Ulcer Classification Models Using Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Techniques: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e69408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Saeedi, P.; Karuranga, S.; Pinkepank, M.; Ogurtsova, K.; Duncan, B.B.; Stein, C.; Basit, A.; Chan, J.C.; Mbanya, J.C.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lazzarini, P.A.; McPhail, S.M.; van Netten, J.J.; Armstrong, D.G.; Pacella, R.E. Global disability burdens of diabetes-related lower-extremity complications in 1990 and 2016. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Li, S.H.; El Akkawi, M.M.; Fu, X.B.; Liu, H.W.; Huang, Y.S. Surgical amputation for patients with diabetic foot ulcers: A Chinese expert panel consensus treatment guide. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 1003339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabetic Podiatry Group, Peripheral Vascular Diseases Committee of Chinese Microcirculation Society. Expert Consensus on diabetic foot wound repair and treatment. Chin. J. Diabetes 2018, 10, 305–309. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Medical Association Diabetes Society, Chinese Medical Association Infectious Diseases Society, Chinese Medical Association Tissue Repair and Regeneration Society. Chinese Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of diabetic foot (2019 edition) (Ⅳ). Chin. J. Diabetes 2019, 11, 316–327. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, T. Comparison of Wagner grading method for diabetic foot and University of TEXAS classification. Chin. J. Diabetes 2012, 4, 469–473. [Google Scholar]

- Monteriro-Soares, M.; Russell, D.; Boyko, E.J.; Jeffcoate, W.; Mills, J.L.; Morbach, S.; Game, F.; Wang, A.H.; Ran, X.W.; Department of Community Medicine, Health Information and Decisions; et al. International Diabetic Foot Working Group: Classification of diabetic foot ulcers Part of the International Diabetic Foot Working Group: International Guidelines for Diabetic Foot Management (2019). Infect. Inflamm. Repair. 2019, 20, 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, Y. Serum albumin is a good clinical indicator for predicting the risk of amputation and medical cost of diabetic foot ulcer. Chin. J. Geriatr. Multi-Organ Dis. 2013, 12, 919–923. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Xu, R. A systematic evaluation of risk prediction model for diabetic foot. Chin. J. Nurs. 2021, 56, 124–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam, J.; Cook, J.A.; Collins, G.S. Clinical prediction models. Br. J. Surg. 2016, 103, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, K.G.; Altman, D.G.; Reitsma, J.B.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Macaskill, P.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Vicker, A.J.; Ransohoff, D.F.; Collins, G.S. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, W1–W73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, A.; Lunt, M.; Rutter, M.K.; Anderson, S.G.; Cortes, G.; Edmonds, M.; Jude, E.; Boulton, A.; Dunn, G. Developing a foot ulcer risk model: What is needed to do this in a real-world primary care setting? Diabet. Med. 2019, 36, 1412–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Manning, W.G.; Mullahy, J. Comparing alternative models: Log vs cox proportional hazard? Health Econ. 2004, 13, 749–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.E. Logistic regression. In Reading and Understanding Multivariate Statistics; American Psychological Association: Washington, WA, USA, 1995; pp. 217–244. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, R.; Nath, A.; Patel, S.; Mohapatra, E. Machine learning algorithm to evaluate risk factors of diabetic foot ulcers and its severity. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2022, 60, 2349–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zale, A.; Mathioudakis, N. Machine learning models for inpatient glucose prediction. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2022, 22, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Xie, P.; Chen, Y.; Rui, S.; Yang, C.; Deng, B.; Wang, M.; Armstrong, D.G.; Ma, Y.; Deng, W. Impact of acute hyperglycemic crisis episode on survival in individuals with diabetic foot ulcer using a machine learning approach. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 974063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brereton, R.G.; Lloyd, G.R. Support vector machines for classification and regression. Analyst 2010, 135, 230–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, D.; Nilsson, J.; Andersson, R.; Regnér, S.; Tingstedt, B.; Andersson, B. Artificial neural networks predict survival from pancreatic cancer after radical surgery. Am. J. Surg. 2013, 205, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, Z.; Mohammad, K.; Mahmoudi, M.; Parsaeian, M.; Zeraati, H. Assessing the effect of quantitative and qualitative predictors on gastric cancer individuals survival using hierarchical artifcial neural network models. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2013, 15, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Li, J.; Huang, A.; Yan, Z.; Lau, W.Y.; Shen, F. Artificial neural networking model for the prediction of post -hepatectomy survival of patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 29, 2014–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality tests for statistical analysis: A guide for non-statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, P.D.; Sawilowsky, S.S. Increasing physicians’ awareness of the impact of statistics on research outcomes: Comparative power of the t-test and and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test in small samples applied research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1999, 52, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.L. The chi-square test of independence. Biochem. Med. 2013, 23, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, X.; Lu, J.; Pan, J. Lasso regression: From interpretation to prediction. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 28, 1777–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Carreras, D.; Alcaraz, J.; Landete, M. Comparing two SVM models through different metrics based on the confusion matrix. Comput. Oper. Res. 2023, 152, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, I.R.; Ahmed, M.O.; Sabir, E.I.; Alsheneber, I.F.; Ibrahim, E.M.; Mohamed, G.B.; Awadallah, R.E.; Abbas, T.; Gasim, G.I. Factors associated with amputation among patients with diabetic foot ulcers in a Saudi population. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Chen, M. Analysis of related factors of diabetic foot ulcer healing and amputation. J. Anhui Med. Univ. 2016, 51, 1634–1637. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.-H.; Tsai, J.-S.; Huang, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Yang, H.-M.; Chan, Y.-S.; Hsieh, S.-H.; Hsu, B.R.-S.; Huang, Y.-Y. Risk factors for lower extremity amputation in diabetic foot disease categorized by Wagner classification. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2012, 95, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.X.; Branco, B.C.; Armstrong, D.G.; Mills, J.L., Sr. The Society for Vascular Surgery lower extremity threatened limb classification system based on wound, ischemia, and foot infection (WIfI) correlates with risk of major amputation and time to wound healing. J. Vasc. Surg. 2015, 61, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gau, B.R.; Chen, H.Y.; Hung, S.Y.; Yang, H.M.; Yeh, J.T.; Huang, C.H.; Sun, J.-H.; Huang, Y.-Y. The impact of nutritional status on treatment outcomes of patients with limb-threatening diabetic foot ulcers. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2016, 30, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, J.H.; Huang, D.D.; Li, D.G.; Chen, B.; Zhang, L.M.; Yuan, C.L.; Cai, L.J. Clinical significance of analysis of the level of blood fat, CRP and hemorheological indicators in the diagnosis of elder coronary heart disease. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1812–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehraj, M.; Shah, I. A review of Wagner classification and current concepts in management of diabetic foot. Int. J. Orthop. Sci. 2018, 4, 933–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Chen, R.; Wei, W.; Lu, X. Understanding heart-failure patients EHR clinical features via SHAP interpretation of tree-based machine learning model predictions. arXiv 2021, arXiv:210311254. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, B.J.; Choi, H.J.; Kang, J.S.; Tak, M.S.; Park, E.S. Comparison of five systems of classification of diabetic foot ulcers and predictive factors for amputation. Int. Wound J. 2017, 14, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyko, E.J.; Ahroni, J.H.; Cohen, V.; Nelson, K.M.; Heagerty, P.J. Prediction of diabetic foot ulcer occurrence using commonly available clinical information: The seattle diabetic foot study. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, M.; Kabeya, Y.; Okisugi, M.; Kawasaki, M.; Katsuki, T.; Oikawa, Y.; Shimada, A.; Atsumi, Y. Development and assessment of a simple scoring system for the risk of developing diabetic foot. Diabetol. Int. 2015, 6, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Min, R.; Liao, Y.; Yu, A. Development of Predictive Nomograms for Clinical Use to Quantify the Risk of Amputation in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcer. Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 6621035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Li, R.; Yuan, L.; Huang, F.-M.; Wang, Y.; He, T.; Ye, Z.-W. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for foot ulcers in diabetic patients. Diabetes Res. 2023, 2023, 1199885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santema, T.B.; Lenselink, E.A.; Balm, R.; Ubbink, D.T. Comparing the Meggitt-Wagner and the University of Texas wound classification systems for diabetic foot ulcers: Inter-observer analyses. Int. Wound J. 2016, 13, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckert, S.; Witte, M.; Wicke, C.; Königsrainer, A.; Coerper, S. A new wound-based severity score for diabetic foot ulcers: A prospective analysis of 1,000 patients. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 988–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripatti, S.; Tikkanen, E.; Orho-Melander, M.; Havulinna, A.S.; Silander, K.; Sharma, A.; Guiducci, C.; Perola, M.; Jula, A.; Sinisalo, J.; et al. A multilocus genetic risk score for coronary heart disease: Case-control and prospective cohort analyses. Lancet 2010, 376, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.; Chen, P.; Li, R.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wong, T.Y.; Tai, E.S.; Teo, Y.-Y.; Montana, G. Pathways-driven sparse regression identifies pathways and genes associated with high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in two asiancohorts. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wei, D.; Wang, J.; Gao, L. Predicting major amputation risk in diabetic foot ulcers using comparative machine learning models for enhanced clinical decision-making. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age | Gender | CRP | PCT | WBC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median [Min, Max] | Male | Female | Mean (SD) | Median [Min, Max] | Mean (SD) | Median [Min, Max] | Mean (SD) | Median [Min, Max] | ||

| Training Dataset | non-amputation (n = 66) | 64.8 (11.9) | 65.0 [34.0, 91.0] | 47 (71.2%) | 19 (28.8%) | 36.0 (51.9) | 14.0 [0.400, 292] | 0.249 (0.704) | 0.05 [0.01, 4.98] | 9.09 (3.80) | 7.83 [2.00, 26.4] |

| amputation (n = 54) | 63.7 (11.5) | 64.0 [39.0, 88.0] | 41 (75.9%) | 13 (24.1%) | 137 (93.5) | 122 [1.15, 411] | 0.859 (1.99) | 0.175 [0.02, 11.1] | 12.0 (5.84) | 11.4 [3.96, 31.1] | |

| p-values | 0.601 | 0.561 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.0042 | ||||||

| Validation Dataset | non-amputation (n = 15) | 67.2 (14.1) | 67.0 [42.0, 88.0] | 9 (60.0%) | 6 (40%) | 48.2 (72.7) | 18.2 [1.23, 265] | 0.438 (0.934) | 0.08 [0.03, 3.59] | 10.2 (5.88) | 8.67 [4.93, 24.9] |

| Amputation (n = 14) | 66.4 (16.6) | 65.5 [39.0, 96.0] | 8 (57.1%) | 6 (42.9%) | 125 (88.7) | 106 [2.46, 332] | 0.311(0.729) | 0.045 [0.02, 2.76] | 12.2 (5.60) | 9.85 [5.14, 22.8] | |

| p-values | 0.884 | 1 | 0.006 | 0.154 | 0.183 | ||||||

| Albumin | Hyperlipemia | Wagner Rating | Angiosclerosis | Degree of Occlusion | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median [Min, Max] | No | Yes | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Mild | Moderate | Severe | 0 | 50% | 75% | 99% | ||

| Training Dataset | non-amputation (n = 66) | 34.6 (5.95) | 34.7 [17.1, 46.4] | 50 (75.8%) | 16 (24.2%) | 29 (43.9%) | 23 (34.8%) | 14 (21.2%) | 4 (6.1%) | 2 (3.0%) | 60 (90.9%) | 33 (50.0%) | 2 (3.0%) | 4 (6.1%) | 27 (40.9%) |

| amputation (n = 54) | 33.7 (4.68) | 33.7 [20.5, 45.1] | 37 (68.5%) | 17 (31.5%) | 1 (1.9%) | 11 (20.4%) | 42 (77.8%) | 4 (7.4%) | 0 (0%) | 50 (92.6%) | 18 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (16.7%) | 27 (50.0%) | |

| p-values | 0.385 | 0.377 | <0.001 | 0.647 | 0.0609 | ||||||||||

| Validation Dataset | non-amputation (n = 15) | 33.4 (5.84) | 34.7 [23.0, 43.0] | 11 (73.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 5 (33.3%) | 7 (46.7%) | 3 (20.0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 14 (93.3%) | 7 (46.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (53.3%) |

| Amputation (n = 14) | 32.7 (6.14) | 32.8 [22.7, 44.4] | 9 (64.3%) | 5 (35.7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (14.3%) | 12 (85.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (100%) | 7 (50.0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (21.4%) | 4 (28.6%) | |

| p-values | 0.756 | 0.7 | 0.00103 | 1 | 0.16 | ||||||||||

| β | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −5.1546 | ||

| Angiosclerosis moderate | −17.8435 | <0.001 | 0.994 |

| Angiosclerosis severe | 0.3903 | 1.477[0.119, 18.306] | 0.761 |

| CRP | 0.0207 | 1.021[1.010,1.032] | <0.001 |

| Degree of occlusion 50 | −16.5541 | <0.001 | 0.994 |

| Degree of occlusion 75 | 1.1200 | 3.065[0.367, 25.597] | 0.301 |

| Degree of occlusion 99 | −0.0199 | 0.980[0.277, 3.473] | 0.975 |

| Wagner rating3 | 2.7226 | 15.220[1.535, 150.867] | 0.020 |

| Wagner rating4 | 4.3520 | 77.630[8.152, 739.265] | <0.001 |

| Model | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | Precision | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | 0.81 | 0.723 | 0.777 | 0.795 | 0.745 | 0.734 |

| KNN | 0.78 | 0.722 | 0.851 | 0.819 | 0.808 | 0.763 |

| SVM | 0.89 | 0.796 | 0.865 | 0.824 | 0.828 | 0.812 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, L.; Liu, Z.; Han, S.; Wang, J. A Machine-Learning-Based Clinical Decision Model for Predicting Amputation Risk in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Diagnostic Performance and Practical Implications. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243142

Gao L, Liu Z, Han S, Wang J. A Machine-Learning-Based Clinical Decision Model for Predicting Amputation Risk in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Diagnostic Performance and Practical Implications. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243142

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Lei, Zixuan Liu, Siyang Han, and Jiangning Wang. 2025. "A Machine-Learning-Based Clinical Decision Model for Predicting Amputation Risk in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Diagnostic Performance and Practical Implications" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243142

APA StyleGao, L., Liu, Z., Han, S., & Wang, J. (2025). A Machine-Learning-Based Clinical Decision Model for Predicting Amputation Risk in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Diagnostic Performance and Practical Implications. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3142. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243142