Anti-NMDA-Receptor GluN1 Antibody Serostatus Is Robust in Acute Severe Stroke

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Blood Sampling and Anti-NMDA-Receptor Antibody Measurement

2.3. Definition of Titer Change

2.4. Clinical Outcome Exploration

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.6. Ethics Statement

2.7. Data Availability

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Data

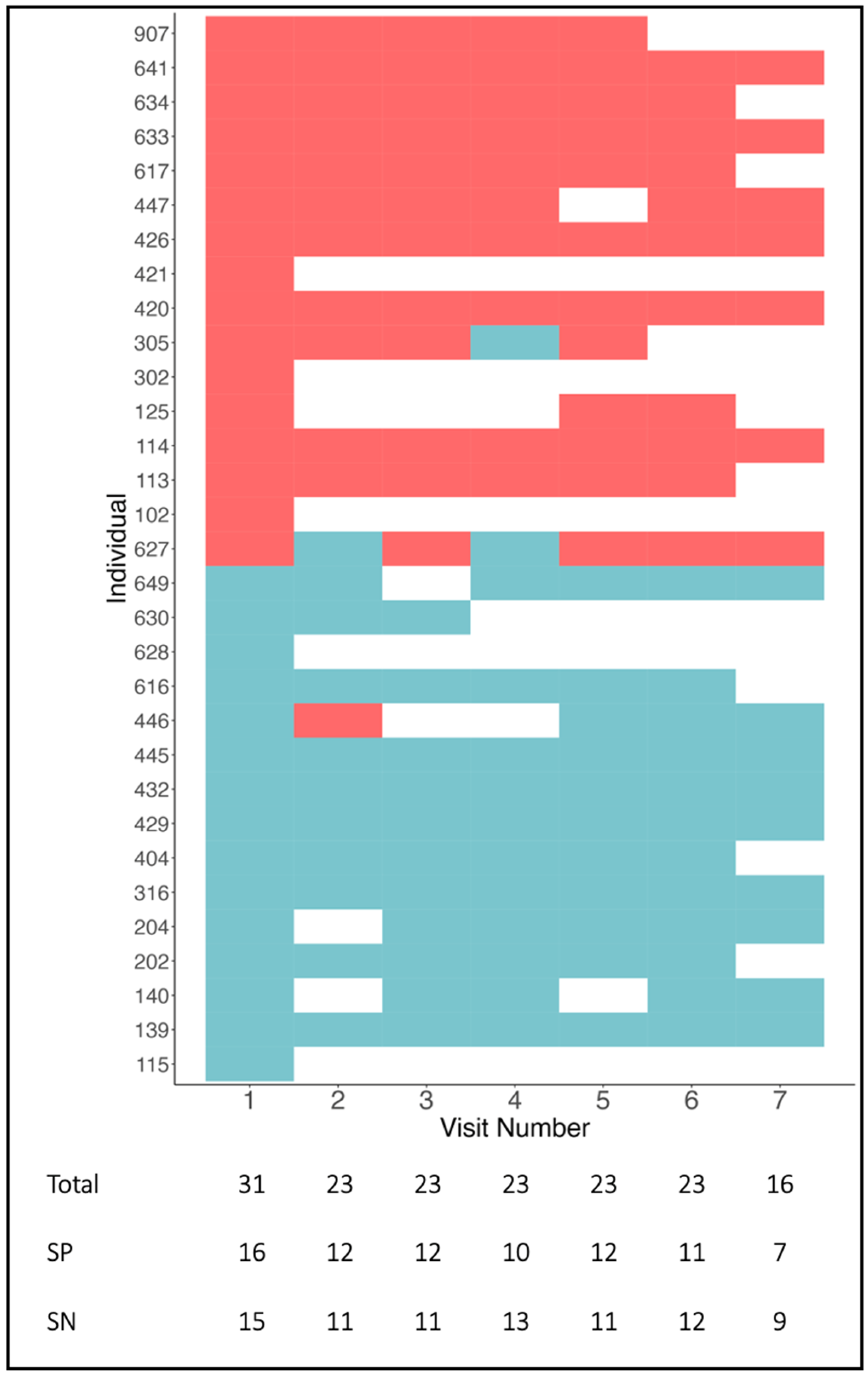

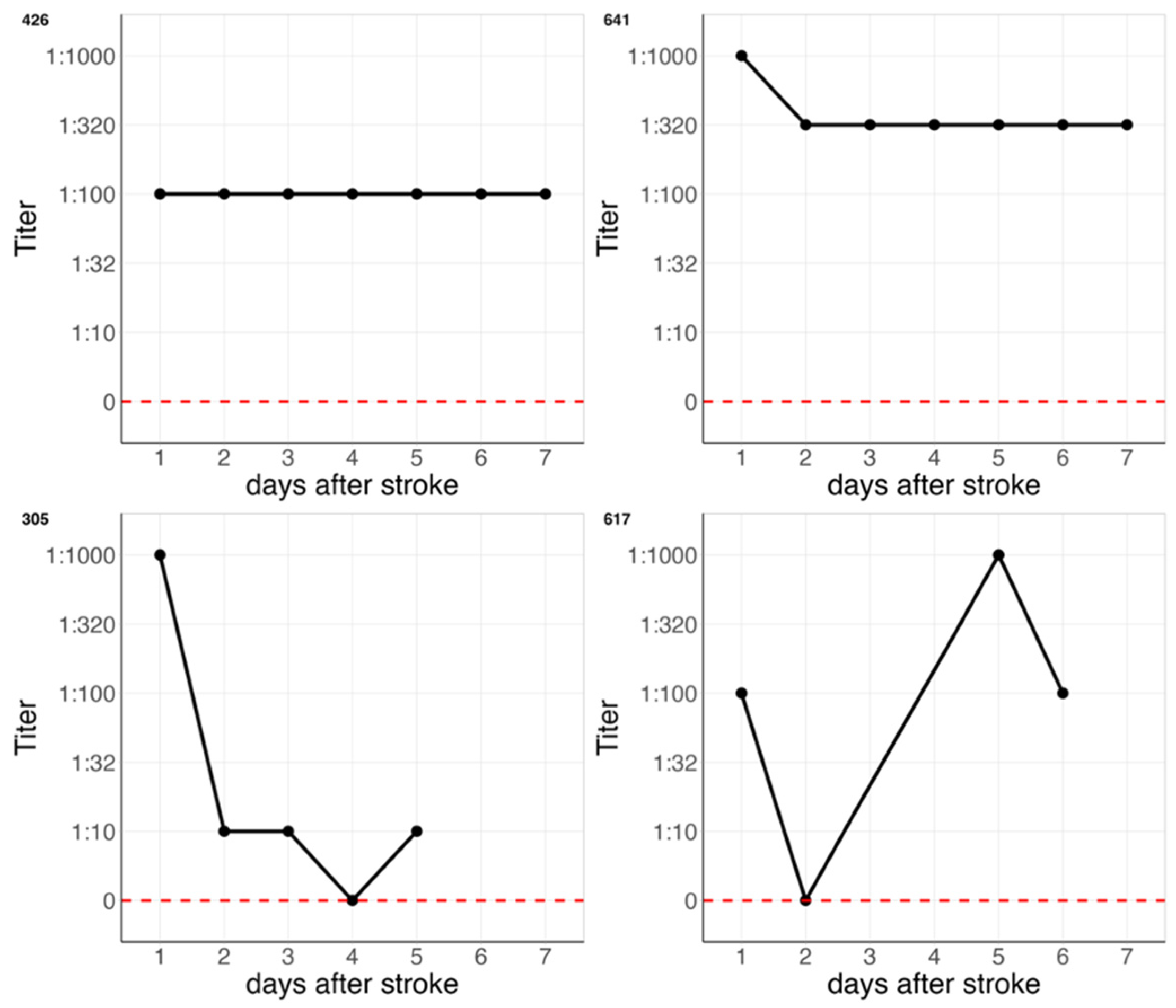

3.2. Follow-Up Data

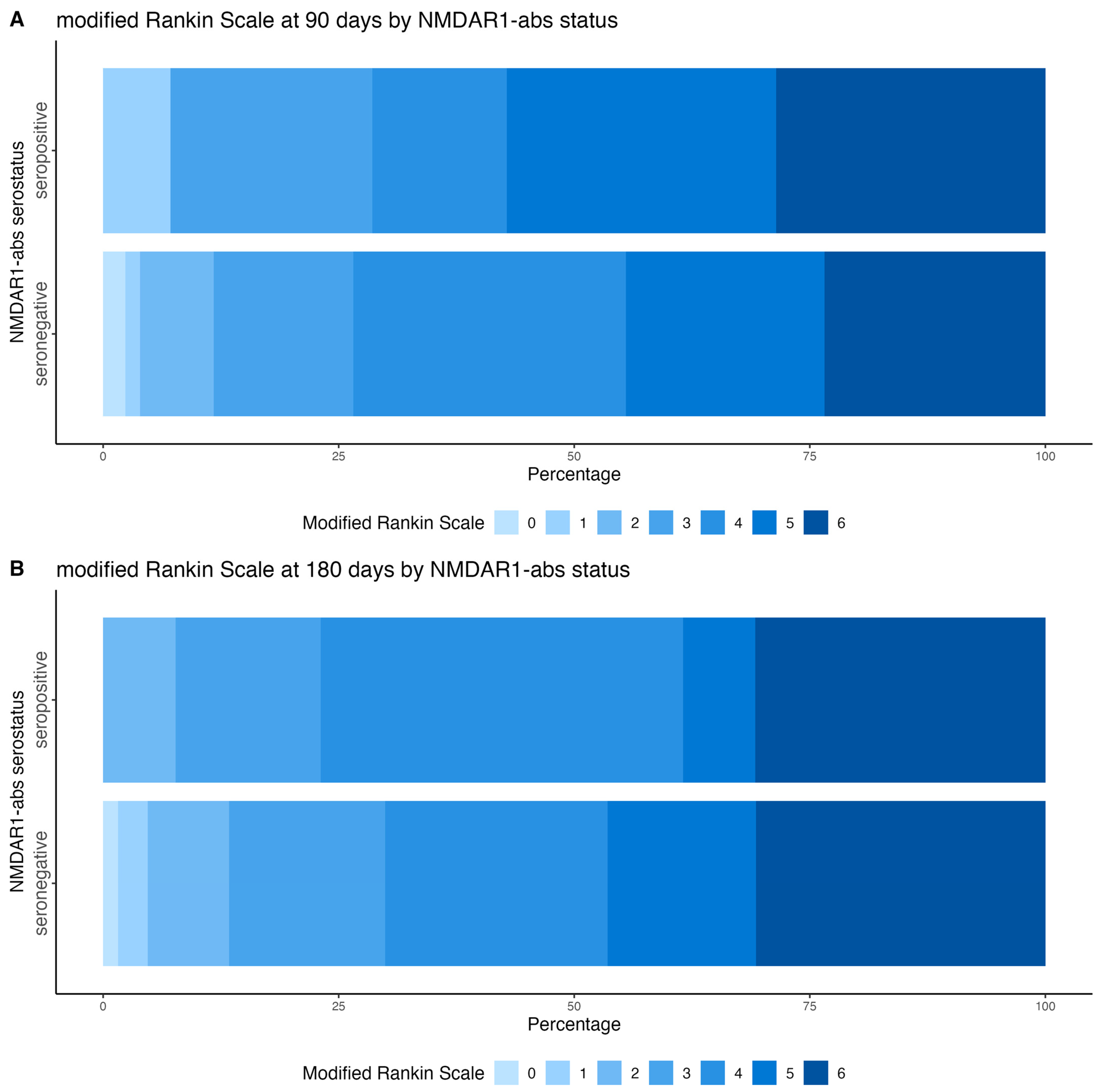

3.3. Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days and 6 Months After Stroke

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dalmau, J.; Tuzun, E.; Wu, H.Y.; Masjuan, J.; Rossi, J.E.; Voloschin, A.; Baehring, J.M.; Shimazaki, H.; Koide, R.; King, D.; et al. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann. Neurol. 2007, 61, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doss, S.; Wandinger, K.P.; Hyman, B.T.; Panzer, J.A.; Synofzik, M.; Dickerson, B.; Mollenhauer, B.; Scherzer, C.R.; Ivinson, A.J.; Finke, C.; et al. High prevalence of NMDA receptor IgA/IgM antibodies in different dementia types. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2014, 1, 822–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahm, L.; Ott, C.; Steiner, J.; Stepniak, B.; Teegen, B.; Saschenbrecker, S.; Hammer, C.; Borowski, K.; Begemann, M.; Lemke, S.; et al. Seroprevalence of Autoantibodies against Brain Antigens in Health and Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 76, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daguano Gastaldi, V.; Bh Wilke, J.; Weidinger, C.A.; Walter, C.; Barnkothe, N.; Teegen, B.; Luessi, F.; Stöcker, W.; Lühder, F.; Begemann, M.; et al. Factors predisposing to humoral autoimmunity against brain-antigens in health and disease: Analysis of 49 autoantibodies in over 7000 subjects. Brain Behav. Immun. 2023, 108, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prüss, H. Autoantibodies in neurological disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 798–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenreich, H. Autoantibodies against N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor 1 in health and disease. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2018, 31, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, F.; Stronisch, T.; Farmer, K.; Rentzsch, K.; Kiecker, F.; Finke, C. Neuronal autoantibodies associated with cognitive impairment in melanoma patients. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, P.S.; Siegerink, B.; Huo, S.; Rohmann, J.L.; Piper, S.K.; Pruss, H.; Heuschmann, P.U.; Endres, M.; Liman, T.G. Serum Anti-NMDA (N-Methyl-D-Aspartate)-Receptor Antibodies and Long-Term Clinical Outcome After Stroke (PROSCIS-B). Stroke 2019, 50, 3213–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, N.R.; Worthmann, H.; Steixner-Kumar, A.A.; Schuppner, R.; Grosse, G.M.; Pan, H.; Gabriel, M.M.; Hasse, I.; van Gemmeren, T.; Lichtinghagen, R.; et al. Autoantibodies against the NMDAR subunit NR1 are associated with neuropsychiatric outcome after ischemic stroke. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 96, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlt, F.A.; Sperber, P.S.; von Rennenberg, R.; Gebert, P.; Teegen, B.; Georgakis, M.K.; Fang, R.; Dewenter, A.; Gortler, M.; Petzold, G.C.; et al. Serum anti-NMDA receptor antibodies are linked to memory impairment 12 months after stroke. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulm, L.; Ohlraun, S.; Harms, H.; Hoffmann, S.; Klehmet, J.; Ebmeyer, S.; Hartmann, O.; Meisel, C.; Anker, S.D.; Meisel, A. STRoke Adverse outcome is associated WIth NoSocomial Infections (STRAWINSKI): Procalcitonin ultrasensitive-guided antibacterial therapy in severe ischaemic stroke patients—Rationale and protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Stroke 2013, 8, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulm, L.; Hoffmann, S.; Nabavi, D.; Hermans, M.; Mackert, B.M.; Hamilton, F.; Schmehl, I.; Jungehuelsing, G.J.; Montaner, J.; Bustamante, A.; et al. The Randomized Controlled STRAWINSKI Trial: Procalcitonin-Guided Antibiotic Therapy after Stroke. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Gomez, E.; Kastner, A.; Steiner, J.; Schneider, A.; Hettling, B.; Poggi, G.; Ostehr, K.; Uhr, M.; Asif, A.R.; Matzke, M.; et al. The brain as immunoprecipitator of serum autoantibodies against N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunit NR1. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 79, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenke, N.K.; Kreye, J.; Andrzejak, E.; van Casteren, A.; Leubner, J.; Murgueitio, M.S.; Reincke, S.M.; Secker, C.; Schmidl, L.; Geis, C.; et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor dysfunction by unmutated human antibodies against the NR1 subunit. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 85, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramberger, M.; Peschl, P.; Schanda, K.; Irschick, R.; Hoftberger, R.; Deisenhammer, F.; Rostasy, K.; Berger, T.; Dalmau, J.; Reindl, M. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of microscopy and flow cytometry in evaluating N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibodies in serum using a live cell-based assay. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thouin, A.; Gastaldi, M.; Woodhall, M.; Jacobson, L.; Vincent, A. Comparison of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody assays using live or fixed substrates. J. Neurol. 2021, 268, 1818–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerche, M.; Weissenborn, K.; Ott, C.; Dere, E.; Asif, A.R.; Worthmann, H.; Hassouna, I.; Rentzsch, K.; Tryc, A.B.; Dahm, L.; et al. Preexisting Serum Autoantibodies Against the NMDAR Subunit NR1 Modulate Evolution of Lesion Size in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2015, 46, 1180–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, H.; Steixner-Kumar, A.A.; Seelbach, A.; Deutsch, N.; Ronnenberg, A.; Tapken, D.; von Ahsen, N.; Mitjans, M.; Worthmann, H.; Trippe, R.; et al. Multiple inducers and novel roles of autoantibodies against the obligatory NMDAR subunit NR1: A translational study from chronic life stress to brain injury. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 2471–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jitprapaikulsan, J.; Fryer, J.P.; Majed, M.; Smith, C.Y.; Jenkins, S.M.; Cabre, P.; Hinson, S.R.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Mandrekar, J.; Chen, J.J.; et al. Clinical utility of AQP4-IgG titers and measures of complement-mediated cell killing in NMOSD. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 7, e727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| STRAWINSKI Total | Missing | NMDAR1-Abs Seronegative | NMDAR1-Abs Seropositive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients n (%) | 166 (100) | 5 (3) | - | 16 (10) |

| Age in years mean (SD) | 76 (11) | 76 (11) | 77 (11) | |

| Female sex n (%) | 92 (55) | 87 (58) | 5 (31) | |

| NIHSS median (IQR) | 15 (12–18) | 15 (12–18) | 15 (12–16.5) | |

| Moderate stroke event NIHSS 9–15 n (%) | 102 (61) | 92 (61) | 10 (63) | |

| Severe stroke event NIHSS > 15 n (%) | 64 (39) | 58 (39) | 6 (38) | |

| Previous stroke event n (%) | 41 (25) | 8 (5) | 37 (25) | 4 (25) |

| History of hypertension n (%) | 147 (86) | 131 (87) | 16 (100) | |

| History of diabetes n (%) | 48 (29) | 4 (2) | 40 (27) | 8 (50) |

| History of atrial fibrillation n (%) | 84 (51) | 7 (4) | 75 (50) | 9 (56) |

| Smokers n (%) | 23 (14) | 25 (15) | 21 (14) | 2 (12.5) |

| Care situation before stroke n (%) | ||||

| Independent at home | 121 (73) | 111 (74) | 10 (63) | |

| Home care | 25 (15) | 24 (16) | 1 (6) | |

| Care facility | 20 (12) | 15 (10) | 5 (30) | |

| TOAST n (%) | 2 (1) | |||

| LAA | 45 (27) | 39 (26) | 6 (38) | |

| CE | 81 (49) | 73 (49) | 8 (50) | |

| SVD | 5 (3) | 5 (3) | 0 | |

| Undetermined | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 | |

| Unknown | 30 (18) | 28 (19) | 2 (13) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sperber, P.S.; Hotter, B.; Endres, M.; Prüss, H.; Meisel, A. Anti-NMDA-Receptor GluN1 Antibody Serostatus Is Robust in Acute Severe Stroke. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243132

Sperber PS, Hotter B, Endres M, Prüss H, Meisel A. Anti-NMDA-Receptor GluN1 Antibody Serostatus Is Robust in Acute Severe Stroke. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243132

Chicago/Turabian StyleSperber, Pia Sophie, Benjamin Hotter, Matthias Endres, Harald Prüss, and Andreas Meisel. 2025. "Anti-NMDA-Receptor GluN1 Antibody Serostatus Is Robust in Acute Severe Stroke" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243132

APA StyleSperber, P. S., Hotter, B., Endres, M., Prüss, H., & Meisel, A. (2025). Anti-NMDA-Receptor GluN1 Antibody Serostatus Is Robust in Acute Severe Stroke. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3132. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243132