Tear Film Alterations in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

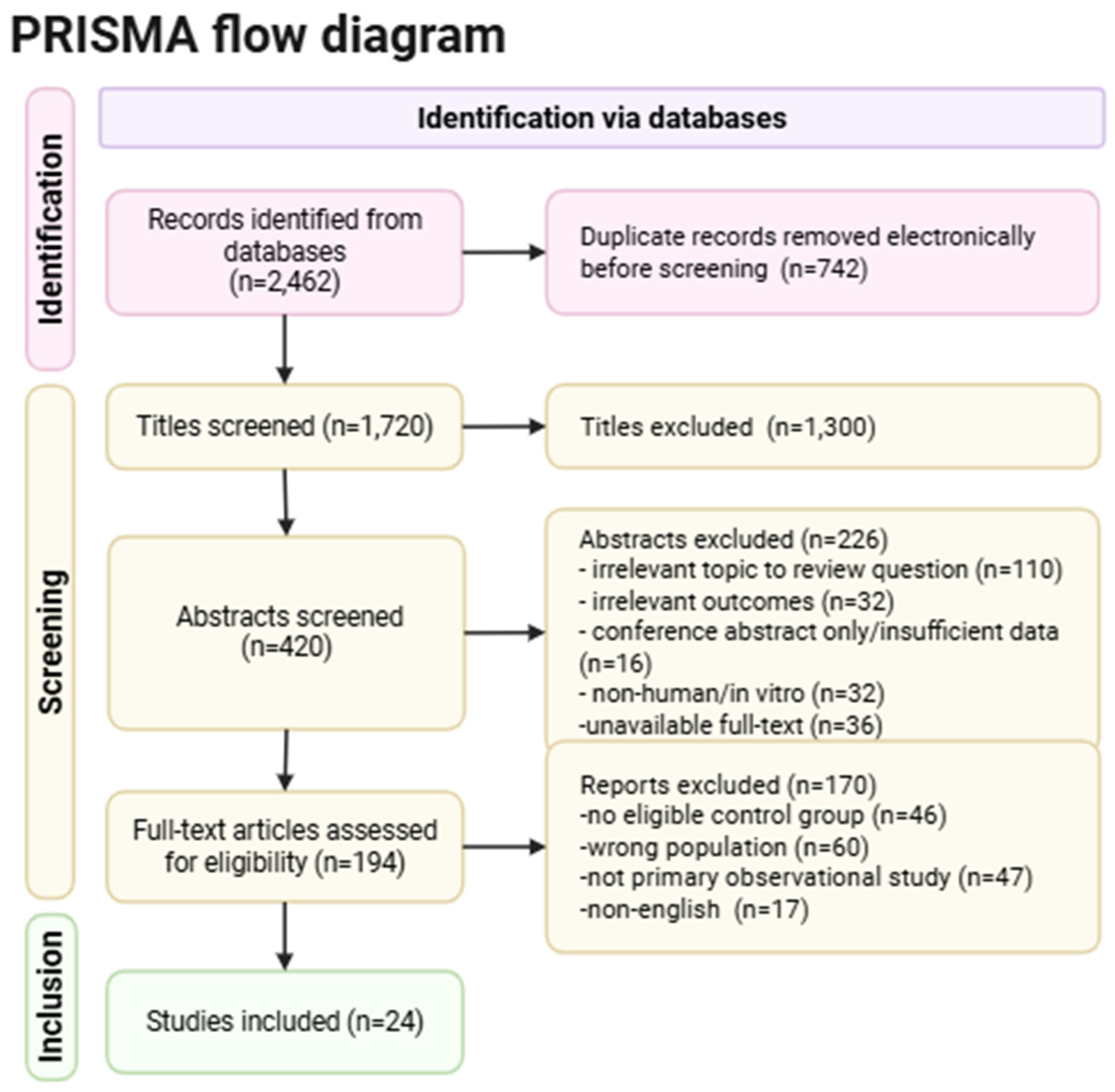

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Methodological Variability

2.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

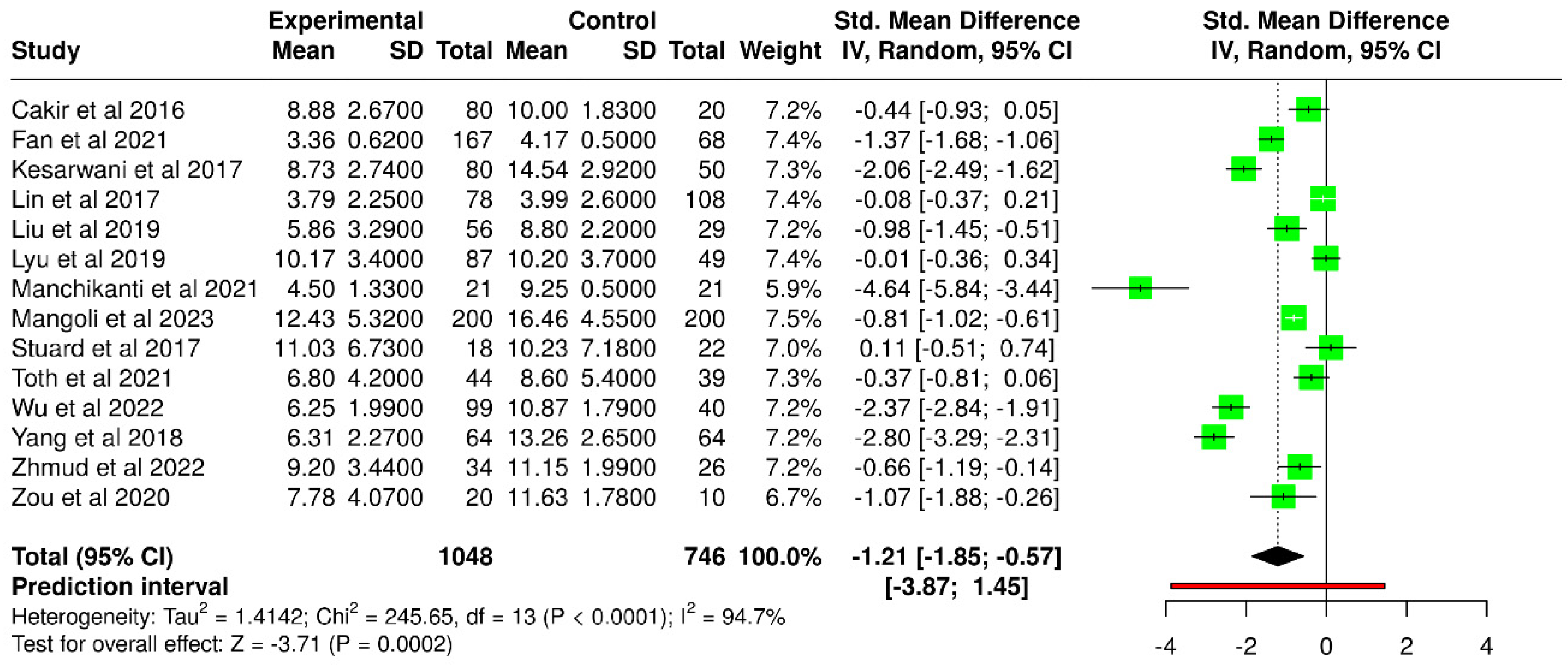

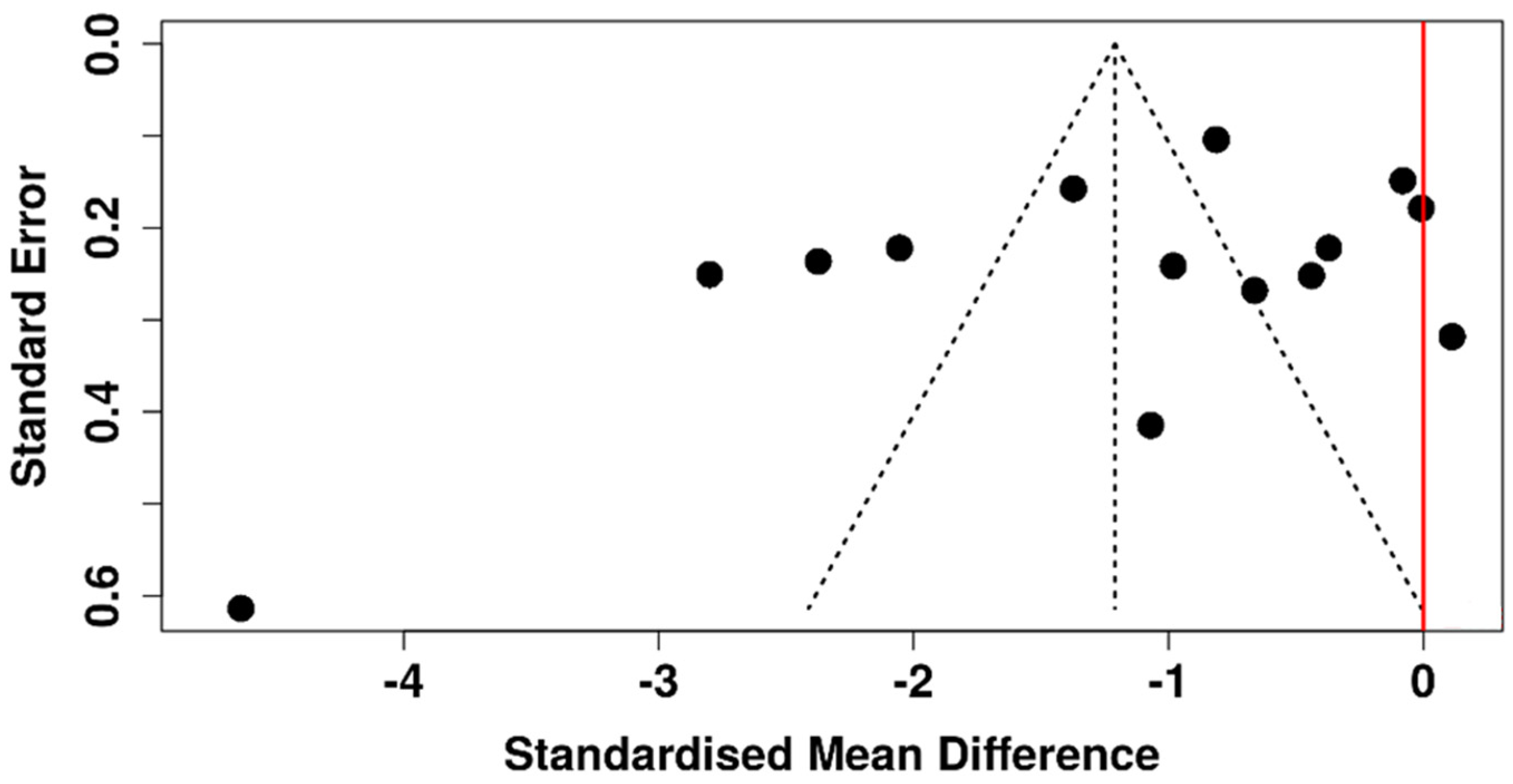

3.1. Invasive Tear Break-Up Time

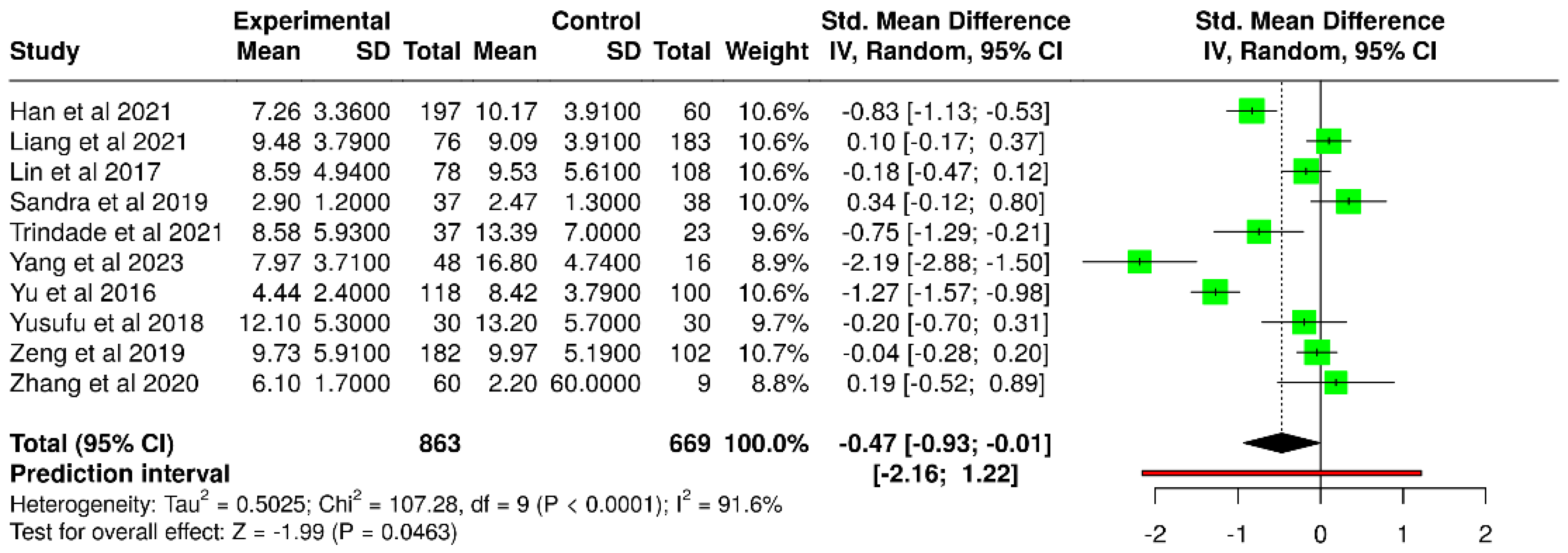

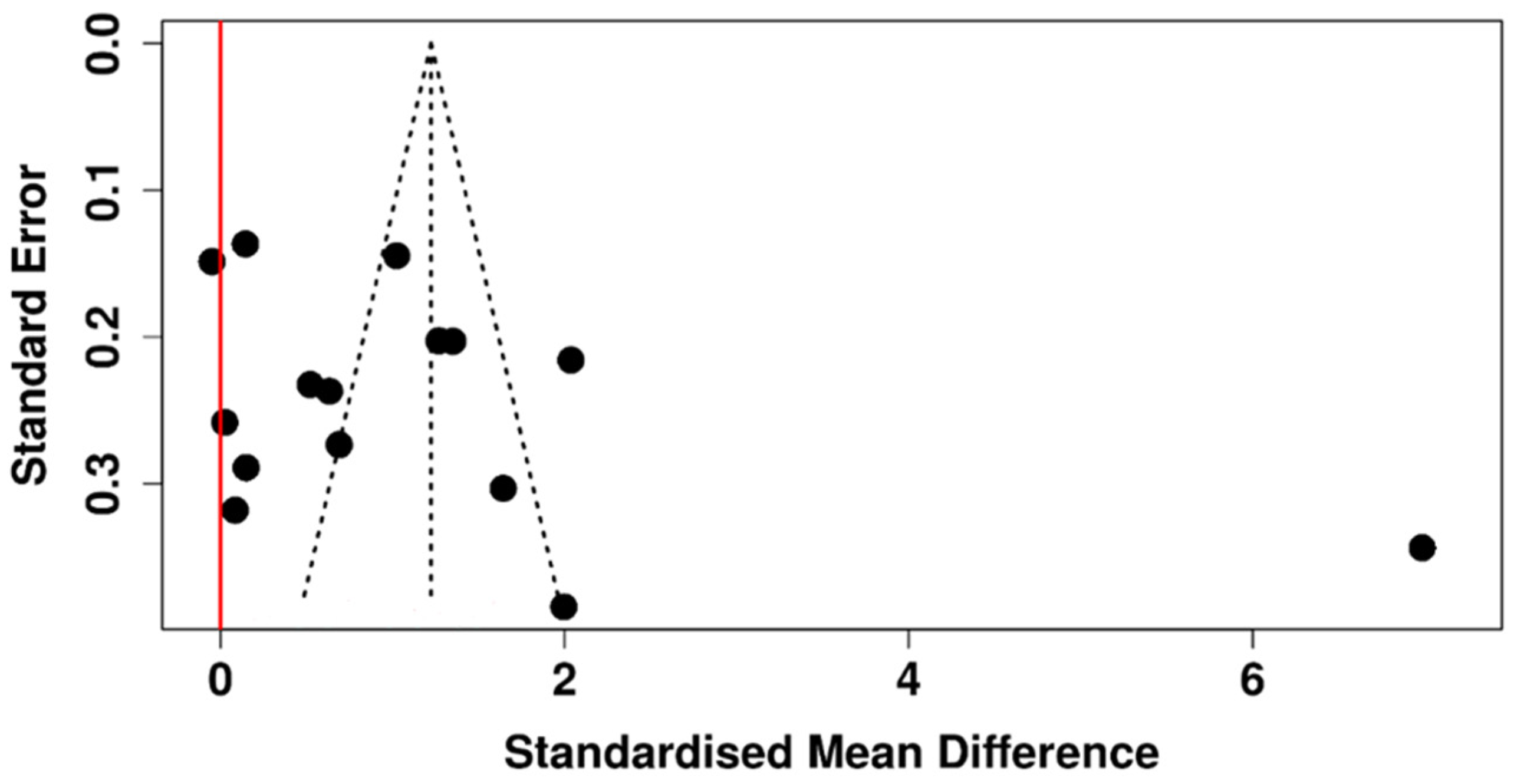

3.2. Non-Invasive Tear Break-Up Time

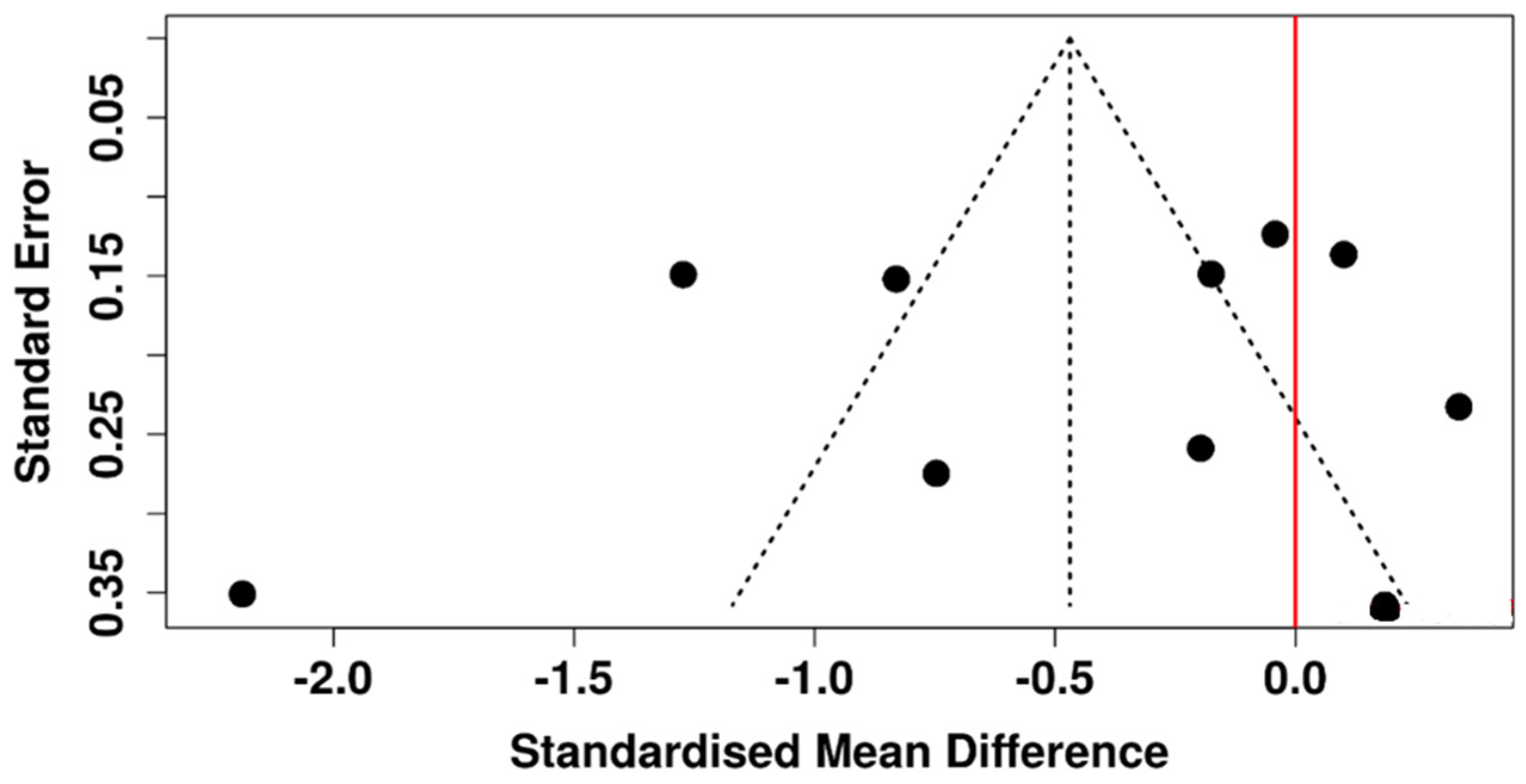

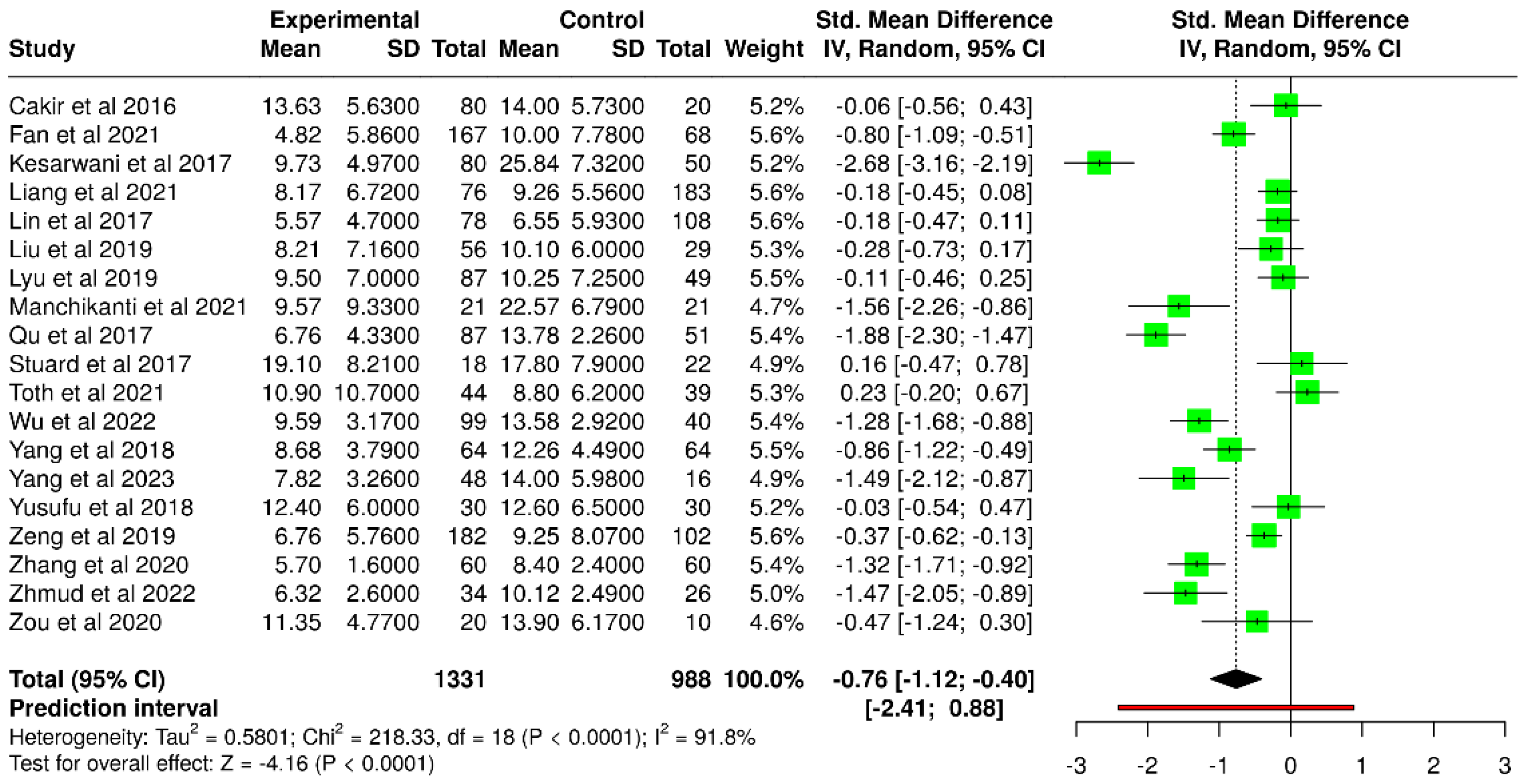

3.3. Schirmer’s Test

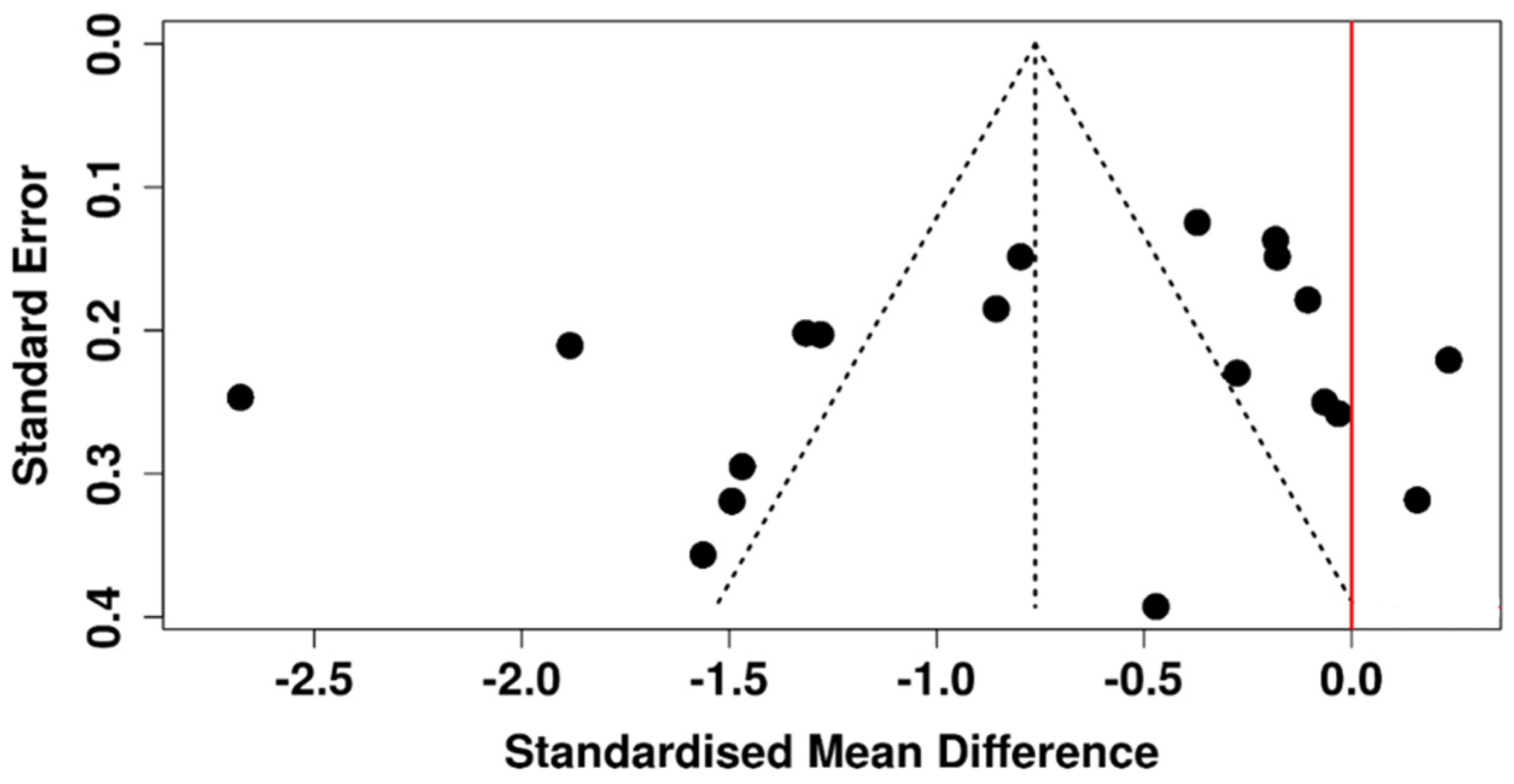

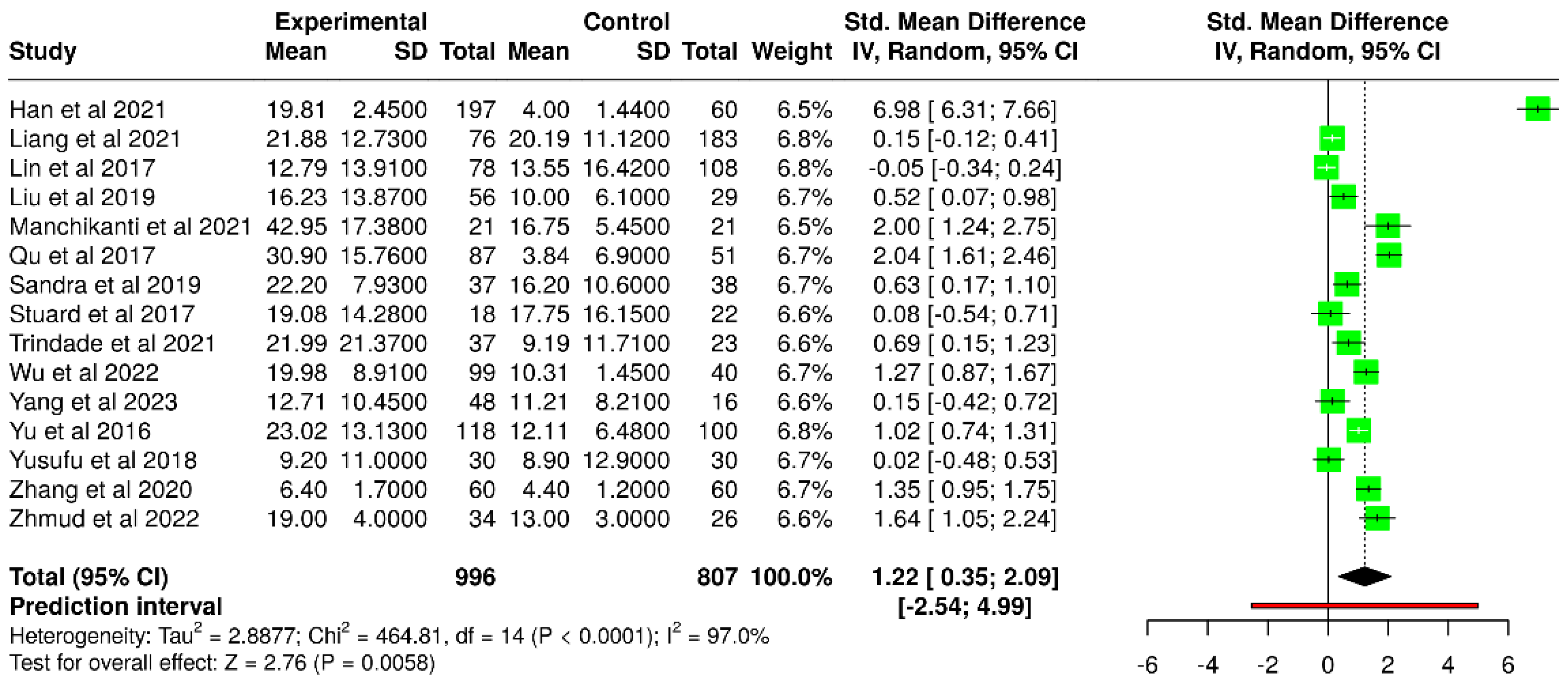

3.4. Ocular Surface Disease Index

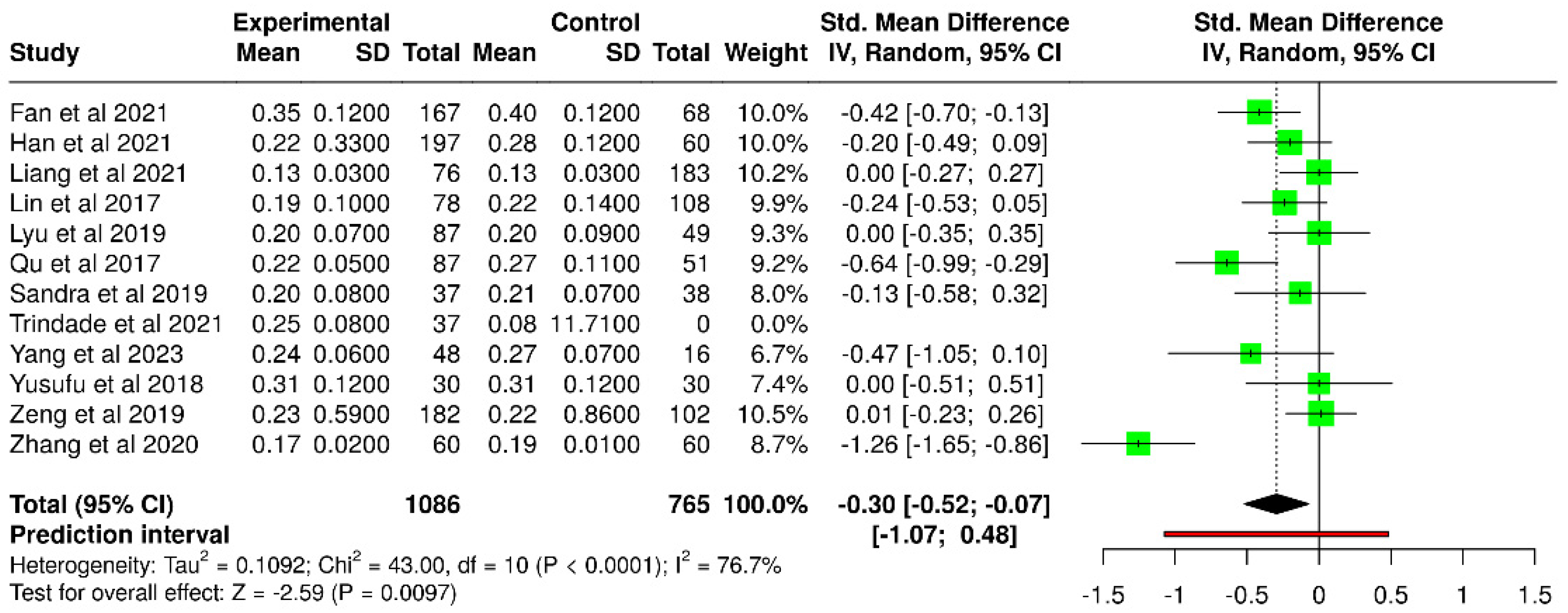

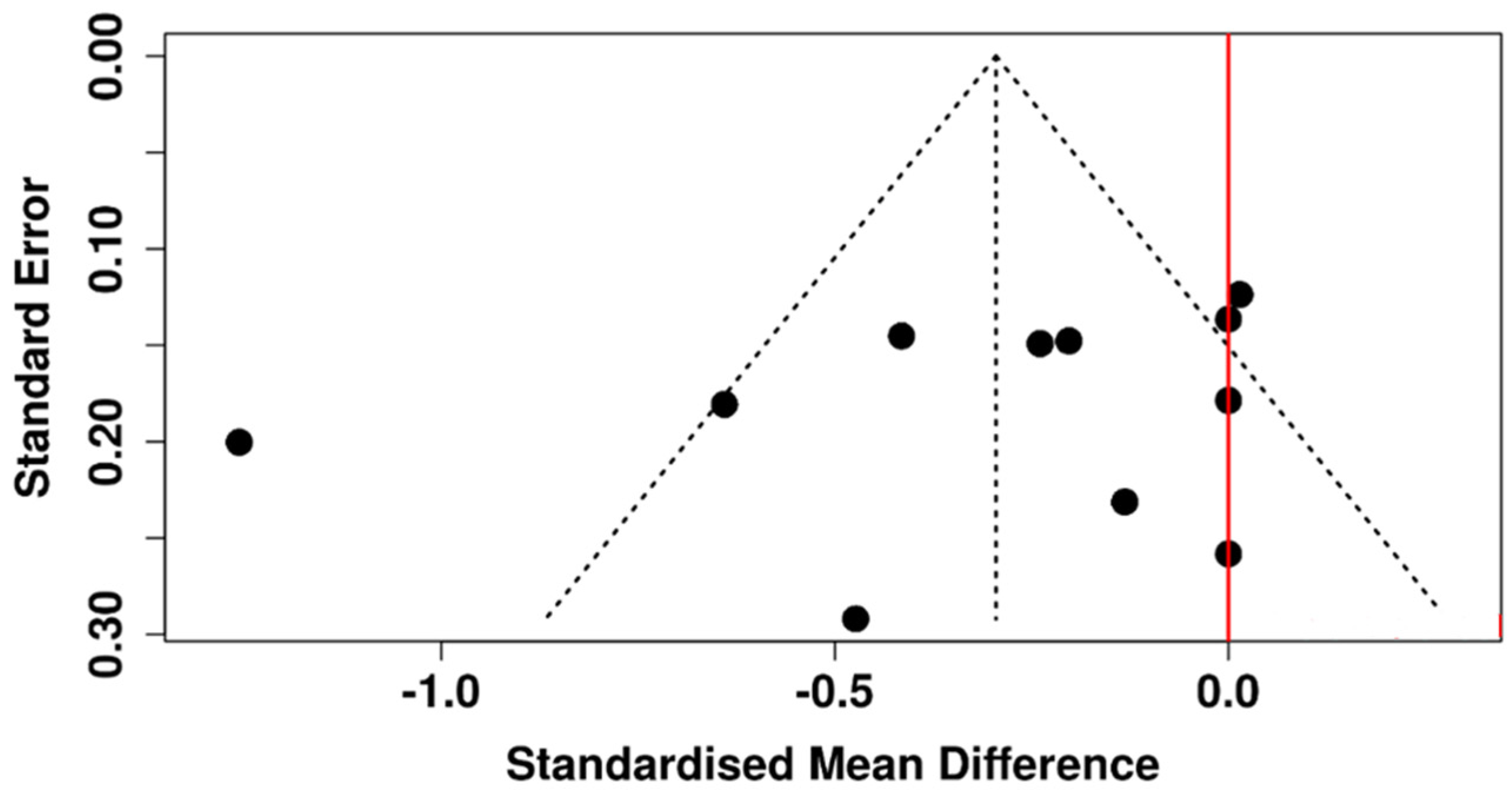

3.5. Tear Meniscus Height

3.6. Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sayin, N. Ocular Complications of Diabetes Mellitus. World J. Diabetes 2015, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, E.W.; Pratt, A.; Owens, A.; Barron, E.; Dunbar-Rees, R.; Slade, E.T.; Hafezparast, N.; Bakhai, C.; Chappell, P.; Cornelius, V.; et al. The Burden of Diabetes-Associated Multiple Long-Term Conditions on Years of Life Spent and Lost. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2830–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.D.; Ong, S.C.; Rafiq, A.; Kalam, M.N.; Sajjad, A.; Abdullah, M.; Malik, T.; Yaseen, F.; Babar, Z.-U.-D. A Systematic Review of the Economic Burden of Diabetes Mellitus: Contrasting Perspectives from High and Low Middle-Income Countries. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2024, 17, 2322107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosu, L.M.; Prodan-Bărbulescu, C.; Maghiari, A.L.; Bernad, E.S.; Bernad, R.L.; Iacob, R.; Stoicescu, E.R.; Borozan, F.; Ghenciu, L.A. Current Trends in Diagnosis and Treatment Approach of Diabetic Retinopathy during Pregnancy: A Narrative Review. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira-Potter, V.J.; Karamichos, D.; Lee, D.J. Ocular Complications of Diabetes and Therapeutic Approaches. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 3801570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Y.-K.; Shao, S.-C.; Lin, E.-T.; Pan, L.-Y.; Yeung, L.; Sun, C.-C. Tear Function in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1036002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Sawai-Ogawa, M.; Kihara, A. Formation of Fatty Alcohols—Components of Meibum Lipids—By the Fatty acyl-CoA Reductase FAR2 Is Essential for Dry Eye Prevention. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskas, V.; Daukantaitė, J.; Galgauskas, S. Rabbit Models of Dry Eye Disease: Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 16, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, K.; Pazo, E.E.; Li, F.; Chang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Yang, R.; Liu, H.; et al. Clinical Ocular Surface Characteristics and Expression of MUC5AC in Diabetics: A Population-Based Study. Eye 2024, 38, 3145–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Luo, X.; Zhang, M.; Bu, J.; Liang, M.; Wu, H.; Yu, J.; He, H.; et al. Hyperglycemia Induces Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, K.; Magdum, R.; Ahuja, A.; Kaul, S.; S, J.; Mishra, A.; Patil, M.; Dhore, D.N.; Alapati, A. Ocular Surface Diseases in Patients with Diabetes. Cureus 2022, 14, e23401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghenciu, L.A.; Hațegan, O.A.; Bolintineanu, S.L.; Dănilă, A.-I.; Faur, A.C.; Prodan-Bărbulescu, C.; Stoicescu, E.R.; Iacob, R.; Șișu, A.M. Immune-Mediated Ocular Surface Disease in Diabetes Mellitus—Clinical Perspectives and Treatment: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, B.D.A.L.; Carneiro, C.L.B.; Gomes, M.S.M.; Nagashima, R.D.; Machado, A.J.; Crispim, J. Clinical Evaluation of Dry Eye Syndrome in Patients with Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy and Laser Therapy Indication. Open Ophthalmol. J. 2019, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Lu, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, J.; He, J.; Zhang, B.; Zou, H. Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics of Dry Eye Disease in Community-Based Type 2 Diabetic Patients: The Beixinjing Eye Study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018, 18, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathebula, S.D.; Mmusi-Landela, L. Pathophysiology of Dry Eye Disease and Novel Therapeutic Agents. Afr. Vis. Eye Health 2024, 83, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, E.V.T.; Huang, J.J.; Mangwani-Mordani, S.; Tovar Vetencourt, A.A.; Galor, A. Individuals with Diabetes Mellitus Have a Dry Eye Phenotype Driven by Low Symptom Burden and Anatomic Abnormalities. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansuri, F.; Bhole, P.K.; Parmar, D. Study of Dry Eye Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Its Association with Diabetic Retinopathy in Western India. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wróbel-Dudzińska, D.; Przekora, A.; Kazimierczak, P.; Ćwiklińska-Haszcz, A.; Kosior-Jarecka, E.; Żarnowski, T. The Comparison between the Composition of 100% Autologous Serum and 100% Platelet-Rich Plasma Eye Drops and Their Impact on the Treatment Effectiveness of Dry Eye Disease in Primary Sjogren Syndrome. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, S.; Samuel, E. Tear Film Breakup Time in Diabetic Patients. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2020, 30, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhanwar, M.; Goyal, S.; Kushwaha, S.; Agrawal, M.; Kamal, V.K.B.M.; Srivastava, A. Comparison of Biomicroscopic Fluorescein Tear Breakup Time with Noninvasive Tear Breakup Time in Diabetic Patients with Dry Eyes. Pan-Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 7, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, I.M.; Khalil, N.M.; El-Gendy, H.A. A Controlled Study on the Correlation between Tear Film Volume and Tear Film Stability in Diabetic Patients. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 2016, 5465272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, H.; Malik, T.G.; Mazhar, A.; Ali, A. Association of Dry Eye Disease with Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2020, 30, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-Y.; Chan, H.-C.; Chan, C.-M. Is There a Link between Dry Eye Disease and Diabetes Mellitus? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2025, 39, 109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin Chan, K.; Liao, X.; Guo, B.; Tse, J.S.H.; Li, P.H.; Cheong, A.M.Y.; Ngo, W.; Lam, T.C. Ocular Surface Parameters Repeatability and Agreement —A Comparison between Keratograph 5M and IDRA. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2024, 47, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Sun, X.; Wei, A.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Qian, T.; Wang, W.; Xu, J. Assessment of Tear Film Stability in Dry Eye with a Newly Developed Keratograph. Cornea 2013, 32, 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeri, F.; Rizzo, G.C.; Ponzini, E.; Tavazzi, S. Comparing Automated and Manual Assessments of Tear Break-up Time Using Different Non-Invasive Devices and a Fluorescein Procedure. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yik, A.L.P.; Barodawala, F.S. Tear Meniscus Height Comparison between AS-OCT and Oculus Keratograph® K5M. Romanian J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 68, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, R.; Takeuchi, G.; Sasai, K.; Nakamura, M.; Akiba, M. Layer-by-Layer Tear Film Measurement in Patients with Dry Eye and Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 18, 2057–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.; Jeon, H.-J.; Yow, K.C.; Hwang, H.S.; Chung, E. Image-Based Quantitative Analysis of Tear Film Lipid Layer Thickness for Meibomian Gland Evaluation. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 2017, 16, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, A.; Ferraro, A.; De Gregorio, C.; Laborante, M.; Coassin, M.; Sgrulletta, R.; Di Zazzo, A. Promising High-Tech Devices in Dry Eye Disease Diagnosis. Life 2023, 13, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovar, A.A.; Frankel, S.T.; Galor, A.; Sabater, A.L. Living with Dry Eye Disease and Its Effects on Quality of Life: Patient, Optometrist, and Ophthalmologist Perspectives. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2023, 12, 2219–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jareebi, M.A.; Akkur, A.A.; Otayf, D.A.H.; Najmi, A.Y.; Mobarki, O.A.; Omar, E.Z.; Najmi, M.A.; Madkhali, A.Y.; Abu Alzawayid, N.A.N.; Darbeshi, Y.M.; et al. Exploring the Prevalence of Dry Eye Disease and Its Impact on Quality of Life in Saudi Adults: A Cross-Sectional Investigation. Medicina 2025, 61, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.H.-P.; Tong, L. The Association of Dry Eye Disease with Functional Visual Acuity and Quality of Life. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Estimating the Sample Mean and Standard Deviation from the Sample Size, Median, Range and/or Interquartile Range. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Wan, X.; Liu, J.; Tong, T. Optimally Estimating the Sample Mean from the Sample Size, Median, Mid-Range, and/or Mid-Quartile Range. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2018, 27, 1785–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakır, B.K.; Katırcıoğlu, Y.; Ünlü, N.; Duman, S.; Üstün, H. Ocular Surface Changes in Patients Treated with Oral Antidiabetic Drugs or Insulin. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 26, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Shi, W.Y.; Song, A.P.; Gao, Y.; Dang, G.F.; Ding, G. Changes of Meibomian Glands in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 1740–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesarwani, D.; Rizvi, S.A.; Khan, A.; Amitava, A.; Vasenwala, S.; Siddiqui, Z. Tear Film and Ocular Surface Dysfunction in Diabetes Mellitus in an Indian Population. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 65, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Xu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Coursey, T.G.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.; Fu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.E. Meibomian Gland Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 2017, 3047867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Tian, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X. Early Central and Peripheral Corneal Microstructural Changes in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients Identified Using in Vivo Confocal Microscopy: A Case-Control Study. Medicine 2017, 96, e7960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuard, W.L.; Titone, R.; Robertson, D.M. Tear Levels of Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Protein 3 Correlate with Subbasal Nerve Plexus Changes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 6105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhao, T.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z. Study on Factors Contributing to Xerophthalmia among Type-2 Diabetes Patients. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 11, 4183–4187. [Google Scholar]

- Yusufu, M.; Liu, X.; Zheng, T.; Fan, F.; Xu, J.; Luo, Y. Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose 2% for Dry Eye Prevention during Phacoemulsification in Senile and Diabetic Patients. Int. Ophthalmol. 2018, 38, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ma, B.; Gao, Y.; Ma, B.; Liu, Y.; Qi, H. Tear Inflammatory Cytokines Analysis and Clinical Correlations in Diabetes and Nondiabetes with Dry Eye. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 200, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Li, F.; Zhao, S. The Effect of the Duration of Diabetes on Dry Eye and Corneal Nerves. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2019, 42, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandra Johanna, G.P.; Antonio, L.-A.; Andrés, G.-S. Correlation between Type 2 Diabetes, Dry Eye and Meibomian Glands Dysfunction. J. Optom. 2019, 12, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Lv, Y.; Gu, Z.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lu, X.; Chu, C.; Gao, Y.; Nie, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. The Effects of Diabetic Duration on Lacrimal Functional Unit in Patients with Type II Diabetes. J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 2019, 8127515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xiang, Y.-H. Analysis of Ocular Surface Dysfunction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. Eye Sci. 2020, 20, 1853–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, P.; Lu, L.; Zou, H. Quantitative Proteomics and Weighted Correlation Network Analysis of Tear Samples in Adults and Children with Diabetes and Dry Eye. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.; Li, X.; Li, K.; Jia, Z. To Find Out the Relationship Between Levels of Glycosylated Hemoglobin with Meibomian Gland Dysfunction in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.X.; Wang, H.; Liang, H.H.; Guo, J.X. Correlation of the Retinopathy Degree with the Change of Ocular Surface and Corneal Nerve in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 14, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Niu, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, L. Alterations of Ocular Surface Parameters in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2021, 14, 3787–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchikanti, V.; Kasturi, N.; Rajappa, M.; Gochhait, D. Ocular Surface Disorder among Adult Patients with Type II Diabetes Mellitus and Its Correlation with Tear Film Markers: A Pilot Study. Taiwan. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 11, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, N.; Silver, D.M.; Balla, S.; Káplár, M.; Csutak, A. In Vivo Corneal Confocal Microscopy and Optical Coherence Tomography on Eyes of Participants with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Obese Participants without Diabetes. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 259, 3339–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, M.; Castro De Vasconcelos, J.; Ayub, G.; Grupenmacher, A.T.; Gomes Huarachi, D.R.; Viturino, M.; Correa-Giannella, M.L.; Atala, Y.B.; Zantut-Wittmann, D.E.; Parisi, M.C.; et al. Ocular Manifestations and Neuropathy in Type 2 Diabetes Patients with Charcot Arthropathy. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 585823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Fang, X.; Luo, S.; Shang, X.; Xie, Z.; Dong, N.; Xiao, X.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Z. Meibomian Glands and Tear Film Findings in Type 2 Diabetic Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 762493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhmud, T.; Drozhzhyna, G.; Malachkova, N. Evaluation and Comparison of Subjective and Objective Anterior Ocular Surface Damage in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Dry Eye Disease. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2023, 261, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangoli, M.V.; Bubanale, S.C.; Bhagyajyothi, B.; Goyal, D. Dry Eye Disease in Diabetics versus Non-Diabetics: Associating Dry Eye Severity with Diabetic Retinopathy and Corneal Nerve Sensitivity. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 1533–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, L.; Li, J.; Yan, H.; Cai, H.; Sheng, M.; Li, B. Evaluation of Meibomian Gland Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes with Dry Eye Disease: A Non-Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023, 23, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, L.; Wang, C.; Zhou, H. Inflammation Mechanism and Anti-Inflammatory Therapy of Dry Eye. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1307682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaido, M.; Arita, R.; Mitsukura, Y.; Ishida, R.; Tsubota, K. Variability of Autonomic Nerve Activity in Dry Eye with Decreased Tear Stability. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMonnies, C.W. The Potential Role of Neuropathic Mechanisms in Dry Eye Syndromes. J. Optom. 2017, 10, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.M.; Kheirkhah, A.; Aggarwal, S.; Abedi, F.; Cavalcanti, B.M.; Cruzat, A.; Hamrah, P. Alterations in Corneal Nerves in Different Subtypes of Dry Eye Disease: An In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Study. Ocul. Surf. 2021, 22, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Li, A.; Zhang, X.; Xu, M.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, L. Meta-Analysis and Review on the Changes of Tear Function and Corneal Sensitivity in Diabetic Patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014, 92, e96–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, M.; Martins, B.; Fernandes, R. Immune Fingerprint in Diabetes: Ocular Surface and Retinal Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Wu, B.; Feng, J.; He, J.; Zang, Y.; Tian, L.; Jie, Y. Relationship between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Changes of the Lid Margin, Meibomian Gland and Tear Film in Dry Eye Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. Ophthalmol. 2025, 45, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Wang, M.T.M.; Craig, J.P. Exploring the Asian Ethnic Predisposition to Dry Eye Disease in a Pediatric Population. Ocul. Surf. 2019, 17, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.P.; Lim, J.; Han, A.; Tien, L.; Xue, A.L.; Wang, M.T.M. Ethnic Differences between the Asian and Caucasian Ocular Surface: A Co-Located Adult Migrant Population Cohort Study. Ocul. Surf. 2019, 17, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schicht, M.; Farger, J.; Wedel, S.; Sisignano, M.; Scholich, K.; Geisslinger, G.; Perumal, N.; Grus, F.H.; Singh, S.; Sahin, A.; et al. Ocular Surface Changes in Mice with Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes and Diabetic Polyneuropathy. Ocul. Surf. 2024, 31, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocan, M.C.; Durukan, I.; Irkec, M.; Orhan, M. Morphologic Alterations of Stromal and Subbasal Nerves in the Corneas of Patients with Diabetes. Cornea 2006, 25, 769–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhou, Y.; Bao, T.; Pang, Y.; Shao, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, W.; Xu, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Impact of Hyperglycemia on Tear Film and Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: A Cross-Sectional Study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2025, 18, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarousha, M.; Badarudin, N.E.; Che Azemin, M.Z. Comparison of Dry Eye Parameters between Diabetics and Non-Diabetics in the District of Kuantan, Pahang. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 23, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Akkul, Z.; Erkilic, K.; Sener, H.; Polat, O.A.; Er Arslantas, E. Diabetic Corneal Neuropathy and Its Relation to the Severity of Retinopathy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Study. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesper, P.L.; Roberts, P.K.; Onishi, A.C.; Chai, H.; Liu, L.; Jampol, L.M.; Fawzi, A.A. Quantifying Microvascular Abnormalities with Increasing Severity of Diabetic Retinopathy Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, BIO307–BIO315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, C.K.; Leitão, C.B.; Azevedo, M.J.; Valiatti, F.B.; Rodrigues, T.C.; Canani, L.H.; Gross, J.L. Diabetic Retinopathy Is Associated with Early Autonomic Dysfunction Assessed by Exercise-Related Heart Rate Changes. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2008, 41, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xie, J.; Xiang, J.; Yan, R.; Liu, J.; Fan, Q.; Lu, L.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Xue, Y.; et al. Corneal Sensory Nerve Injury Disrupts Lacrimal Gland Function by Altering Circadian Rhythms in Mice. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereertbrugghen, A.; Galletti, J.G. Corneal Nerves and Their Role in Dry Eye Pathophysiology. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 222, 109191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, B.T.; Bozkurt, B.; Kerimoglu, H.; Okka, M.; Kamis, U.; Gunduz, K. Effect of Serum Cytokines and VEGF Levels on Diabetic Retinopathy and Macular Thickness. Mol. Vis. 2009, 15, 1906–1914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quevedo-Martínez, J.U.; Garfias, Y.; Jimenez, J.; Garcia, O.; Venegas, D.; Bautista de Lucio, V.M. Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Profile in the Serum of Mexican Patients with Different Stages of Diabetic Retinopathy Secondary to Type 2 Diabetes. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021, 6, e000717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.C.; Pan, L.Y.; Chen, N.N.; Kuo, Y.K.; Chen, T.H. Risk and Protective Factors for Ocular Surface Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 41, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Deng, S.; Sun, X.; Wang, N. Dry Eye Syndrome in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: Prevalence, Etiology, and Clinical Characteristics. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 2016, 8201053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Lee, A.; Lo, A.C.Y.; Kwok, J.S.W.J. Diabetic Corneal Neuropathy: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 816062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaniyan, S.I.; Fasina, O.; Bekibele, C.O.; Ogundipe, A.O. Relationship between Dry Eye and Glycosylated Haemoglobin among Diabetics in Ibadan, Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 33, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study [Reference] | Country | Study Period | Study Design | Groups | Sample Size | Age | Sex M/F | Duration of DM | Mean HbA1c Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | (No. of Patients (Eyes) | (Years, Mean ± SD) | (No.) | (Years, Mean ± SD) | (%, Mean ± SD) | ||||

| Cakir et al. [37] | Turkey | N/A | Cross-sectional | T2DM with OAD | 20 (40) | 53.3 ± 6.8 | 8/12 | 7 | 7.6 ± 0.2 |

| 2016 | T2DM with insulin | 20 (40) | 52.3 ± 7.0 | 6/14 | 6 | 7.7 ± 0.2 | |||

| Yu et al. [38] | China | October 2014–November 2015 | Case–control | T2DM | 118 (118) | 59.7 ± 7.8 | 58/60 | N/A | N/A |

| 2016 | CG | 100 (100) | 60.3 ± 7.6 | 52/48 | - | - | |||

| Kesarwani et al. [39] 2017 | India | N/A | Case–control | T2DM without DR | 29 (38) | 53.0 ± 5.6 | 14/15 | N/A | N/A |

| T2DM with DR | 24 (42) | 52.5 ± 4.8 | 12/12 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| CG | 30 (50) | 51.7 ± 4.8 | 15/15 | - | - | ||||

| Lin et al. [40] | China | May–December 2015 | Prospective | T2DM | 39 (78) | 67.1 ± 1.5 | 16/23 | 9.1 ± 5.4 | N/A |

| 2017 | Case–control | CG | 54 (108) | 67.2 ± 1.7 | 23/31 | - | - | ||

| Qu et al. [41] 2017 | China | March 2015–November 2016 | Prospective Case–control | T2DM without CFS | 48 (48) | 60.5 ± 8.4 | 14/34 | 13.4 ± 8.3 | 7.7 ± 1.1 |

| T2DM with CFS | 39 (39) | 63.8 ± 10.9 | 14/25 | 13.9 ± 5.2 | 7.8 ± 1.8 | ||||

| CG | 51 (51) | 61.5 ± 10.2 | 18/33 | - | - | ||||

| Stuard et al. [42] | USA | N/A | Case–control | T2DM | 18 (18) | 58.8 ± 10.2 | 6/12 | N/A | 7.7 ± 1.0 |

| 2017 | CG | 22 (22) | 53.3 ± 9.7 | 10/12 | - | 5.7 ± 0.4 | |||

| Yang et al. [43] | China | October 2015–June 2017 | Case–control | T2DM | 32 (64) | 53.2 ± 3.8 | 13/19 | N/A | 9.6 ± 2.7 |

| 2018 | CG | 32 (64) | 54.7 ± 3.4 | 14/18 | - | 7.6 ± 2.5 | |||

| Yusufu et al. [44] | China | December 2014–May 2015 | Prospective | T2DM | 30 (30) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2018 | Case–control | CG | 30 (30) | - | - | - | - | ||

| Liu et al. [45] 2019 | China | January–June 2018 | Case–control | T2DM without DED | 24 (24) | 63.5 ± 10.1 | 7/17 | 12.3 ± 6.8 | 8.0 ± 1.6 |

| T2DM with DED | 32 (32) | 61.8 ± 9.8 | 14/18 | 11.3 ± 7.1 | 7.6 ± 1.5 | ||||

| CG | 29 (29) | 62.4 ± 7.5 | 5/24 | - | - | ||||

| Lyu et al. [46] | China | N/A | Prospective | T2DM | 87 (87) | 65 ± 6 | 38/49 | 14 ± 8 | 6.9 ± 0.5 |

| 2019 | Case–control | CG | 49 (49) | 64 ± 5 | 17/32 | - | - | ||

| Sandra et al. [47] | Colombia | N/A | Prospective | T2DM | 37 (37) | 59 ± 7.7 | 37/0 | 7.2 ± 5 | 6.8 ± 0.7 |

| 2019 | Case–control | CG | 36 (36) | 58.5 ± 7.4 | 36/0 | - | - | ||

| Zeng et al. [48] | China | July–September 2017 | Prospective | T2DM | 91 (182) | 65.4 ± 6.3 | 40/51 | 13.6 ± 8.3 | 7.0 ± 0.5 |

| 2019 | Case–control | CG | 51 (102) | 64.4 ± 5.7 | 18/33 | - | - | ||

| Zhang et al. [49] | China | N/A | Case–control | T2DM | 60 (60) | 63.6 ± 11.0 | 32/28 | N/A | N/A |

| 2020 | CG | 60 (60) | 63.4 ± 10.4 | 30/30 | - | - | |||

| Zou et al. [50] 2020 (Adult) | China | August 2017 | Cross-sectional | T2DM without DED | 10 (10) | 57.7 ± 7.2 | 3/7 | 5.7 ± 3.0 | N/A |

| T2DM with DED | 10 (10) | 58.8 ± 4.3 | 4/6 | 12.4 ± 4.5 | N/A | ||||

| CG | 10 (10) | 58.0 ± 4.3 | 3/7 | - | - | ||||

| Fan et al. [51] 2021 | China | May–December 2018 | Cross-sectional | T2DM with HbA1C < 7% | 60 (60) | 58.9 ± 10.0 | 36/24 | N/A | N/A |

| T2DM with HbA1C > 7% | 107 (107) | 56.8 ± 10.0 | 62/45 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| CG | 68 (68) | 58.4 ± 13.6 | 33/35 | - | - | ||||

| Han et al. [52] 2021 | China | June 2019–August 2020 | Cross-sectional | T2DM without DR | 33 (66) | 56.5 ± 7.5 | 16/17 | N/A | N/A |

| T2DM with NPDR | 32 (64) | 58.6 ± 9.4 | 15/17 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| T2DM with PDR | 34 (67) | 57.9 ± 8.2 | 17/17 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| CG | 30 (60) | 56.4 ± 9.5 | 16/14 | - | - | ||||

| Liang et al. [53] | China | December 2019–November 2020 | Cross-sectional | T2DM | 38 (76) | 67.6 ± 9.1 | 16/22 | N/A | N/A |

| 2021 | CG | 92 (183) | 32.8 ± 13.4 | 31/61 | - | - | |||

| Manchikanti et al. [54] | India | July 2016–December 2017 | Case–control | T2DM | 21 (21) | 54.6 ± 11.6 | 19/2 | N/A | N/A |

| 2021 | CG | 21 (21) | 51.3 ± 10.7 | 19/2 | - | - | |||

| Tóth et al. [55] | Hungary | N/A | Cross-sectional | T2DM | 44 (44) | 50 ± 7 | 26/18 | N/A | 7.3 ± 1.1 |

| 2021 | CG | 39 (39) | 53 ± 10 | 16/23 | - | 5.5 ± 0.3 | |||

| Trindade et al. [56] | Brazil | January–September 2019 | Cross-sectional | T2DM without CA | 21 (21) | 60.6 ± 7.9 | 10/11 | 16.2 ± 8.7 | 8.7 ± 1.5 |

| 2021 | T2DM with CA | 16 (16) | 57.1 ± 11.8 | 11/5 | 19 ± 10.1 | 8.5 ± 2.2 | |||

| Wu et al. [57] 2022 | China | January–December 2016 | Cross sectional | T2DM | 99 | 59.72 ± 6.05 | 47/52 | 5.24 ± 3.06 | 7.37 ± 1.28 |

| CG with DED | 33 | 59.09 ± 7.25 | 15/18 | - | 5.96 ± 0.28 | ||||

| CG without DED | 40 | 58.55 ± 7.18 | 21/19 | - | 5.91 ± 0.19 | ||||

| Zhmud et al. [58] | Ukraine | N/A | Cross-sectional | T2DM | 34 | 68.96 ± 8.46 | 18/16 | 6.0 ± 4.8 | 7.28 ± 0.82 |

| 2022 | CG | 26 | 63.76 ± 6.67 | 12/14 | - | - | |||

| Mangoli et al. [59] | India | N/A | Prospective | T2DM | 200 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2023 | Cross-sectional | CG | 200 | - | - | - | - | ||

| Yang et al. [60] 2023 | China | December 2018–December 2019 | Cross-sectional | T2DM with DED | 30 | 64.46 ± 9.29 | 15/15 | 12.15 ± 7.45 | N/A |

| T2DM without DED | 18 | 61.11 ± 6.58 | 11/7 | 12.83 ± 6.71 | N/A | ||||

| CG with DED | 26 | 63.58 ± 8.56 | 10/16 | - | - | ||||

| CG without DED | 16 | 60.06 ± 7.18 | 7/9 | - | - |

| Study | T2DM ITBUT (s) | Number of Subjects | Control ITBUT (s) | Number of Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Çakır et al. [37] | 8.88 ± 2.67 | 80 | 10 ± 1.83 | 20 |

| Fan et al. [51] | 3.36 ± 0.62 | 167 | 4.17 ± 0.50 | 68 |

| Kesarwani et al. [39] | 8.73 ± 2.74 | 80 | 14.54 ± 2.92 | 50 |

| Liu et al. [45] | 5.86 ± 3.29 | 56 | 8.80 ± 2.20 | 29 |

| Manchikanti et al. [54] | 4.50 ± 1.33 | 21 | 9.25 ± 0.50 | 21 |

| Mangoli et al. [59] | 12.43 ± 5.32 | 200 | 16.46 ± 4.55 | 200 |

| Wu et al. [57] | 6.25 ± 1.99 | 99 | 10.87 ± 1.79 | 40 |

| Yang et al. [43] | 6.31 ± 2.27 | 64 | 13.26 ± 2.65 | 64 |

| Zhmud et al. [58] | 9.20 ± 3.44 | 34 | 11.15 ± 1.99 | 26 |

| Zou et al. [50] | 7.78 ± 4.07 | 20 | 11.63 ± 1.78 | 10 |

| Lin et al. [40] * | 3.79 ± 2.25 | 78 | 3.99 ± 2.60 | 108 |

| Lyu et al. [46] * | 10.17 ± 3.40 | 87 | 10.20 ± 3.70 | 49 |

| Stuard et al. [42] * | 11.03 ± 6.73 | 18 | 10.23 ± 7.18 | 22 |

| Tóth et al. [55] * | 6.80 ± 4.20 | 44 | 8.60 ± 5.40 | 39 |

| Study | T2DM NITBUT (s) | Number of Subjects | Control NITBUT (s) | Number of Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Han et al. [52] | 7.26 ± 3.36 | 197 | 10.17 ± 3.91 | 60 |

| Trindade et al. [56] | 8.58 ± 5.93 | 37 | 13.39 ± 7.00 | 23 |

| Yang et al. [43] | 7.97 ± 3.71 | 48 | 16.80 ± 4.74 | 16 |

| Yu et al. [38] | 4.44 ± 2.40 | 118 | 8.42 ± 3.79 | 100 |

| Zhang et al. [49] | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 60 | 9.6 ± 2.2 | 60 |

| Liang et al. [53] * | 9.48 ± 3.79 | 76 | 9.09 ± 3.91 | 183 |

| Lin et al. [40] * | 8.59 ± 4.94 | 78 | 9.53 ± 5.61 | 108 |

| Sandra et al. [47] * | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 37 | 2.47 ± 1.3 | 38 |

| Yusufu et al. [44] * | 12.1 ± 5.3 | 30 | 13.2 ± 5.7 | 30 |

| Zeng et al. [48] * | 9.73 ± 5.91 | 182 | 9.97 ± 5.19 | 102 |

| Study | T2DM (mm) | Number of Subjects | Control (mm) | Number of Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan et al. [51] | 4.82 ± 5.86 | 167 | 10.00 ± 7.78 | 68 |

| Kesarwani et al. [39] | 9.73 ± 4.97 | 80 | 25.84 ± 7.32 | 50 |

| Manchikanti et al. [54] | 9.57 ± 9.33 | 21 | 22.57 ± 6.79 | 21 |

| Qu et al. [41] | 6.76 ± 4.33 | 87 | 13.78 ± 2.26 | 51 |

| Wu et al. [57] | 9.59 ± 3.17 | 99 | 13.58 ± 2.92 | 40 |

| Yang et al. [43] | 8.68 ± 3.79 | 64 | 12.26 ± 4.49 | 64 |

| Yang et al. [60] | 7.82 ± 3.26 | 48 | 14.0 ± 5.98 | 16 |

| Zeng et al. [48] | 6.76 ± 5.76 | 182 | 9.25 ± 8.07 | 102 |

| Zhang et al. [49] | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 60 | 8.4 ± 2.4 | 60 |

| Zhmud et al. [58] | 6.32 ± 2.60 | 34 | 10.12 ± 2.49 | 26 |

| Cakir et al. [37] * | 13.63 ± 5.63 | 80 | 14.00 ± 5.73 | 20 |

| Liang et al. [53] * | 8.17 ± 6.72 | 76 | 9.26 ± 5.56 | 183 |

| Lin et al. [40] * | 5.57 ± 4.70 | 78 | 6.55 ± 5.93 | 108 |

| Liu et al. [45] * | 8.21 ± 7.16 | 56 | 10.1 ± 6.0 | 29 |

| Lyu et al. [46] * | 9.50 ± 7.00 | 87 | 10.25 ± 7.25 | 49 |

| Stuard et al. [42] * | 19.1 ± 8.21 | 18 | 17.8 ± 7.9 | 22 |

| Tóth et al. [55] * | 10.9 ± 10.7 | 44 | 8.8 ± 6.2 | 39 |

| Yusufu et al. [44] * | 12.4 ± 6.0 | 30 | 12.6 ± 6.5 | 30 |

| Zou et al. [50] * | 11.35 ± 4.77 | 20 | 13.90 ± 6.17 | 10 |

| Study | T2DM | Number of Subjects | Control | Number of Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Han et al. [52] | 19.81± 2.45 | 197 | 4.00 ± 1.44 | 60 |

| Liu et al. [45] | 16.23 ± 13.87 | 56 | 10.0 ± 6.1 | 29 |

| Manchikanti et al. [54] | 42.95 ±17.38 | 21 | 16.75 ± 5.45 | 21 |

| Qu et al. [41] | 30.90 ± 15.76 | 87 | 3.84 ± 6.90 | 51 |

| Sandra et al. [47] | 22.2 ± 7.93 | 37 | 16.2 ± 10.60 | 38 |

| Stuard et al. [42] | 19.08 ± 14.28 | 18 | 17.75 ± 16.15 | 22 |

| Trindade et al. [56] | 21.99 ±21.37 | 37 | 9.19 ± 11.71 | 23 |

| Wu et al. [57] | 19.98 ± 8.91 | 99 | 10.31 ± 1.45 | 40 |

| Yang et al. [60] | 12.71 ± 10.45 | 48 | 11.21 ± 8.21 | 16 |

| Yu et al. [38] | 23.02 ±13.13 | 118 | 12.11 ±6.48 | 100 |

| Yusufu et al. [44] | 9.2 ± 11.0 | 30 | 8.9 ± 12.9 | 30 |

| Zhang et al. [49] | 6.4 ± 1.7 | 60 | 4.4 ± 1.2 | 60 |

| Zhmud et al. [58] | 19 ± 4.0 | 34 | 13 ± 3.0 | 26 |

| Liang et al. [53] * | 21.88 ±12.73 | 76 | 20.19 ± 11.12 | 183 |

| Lin et al. [40] * | 12.79 ± 13.91 | 78 | 13.55 ± 16.42 | 108 |

| Study | T2DM TMH (μm) | Number of Subjects | Control TMH (μm) | Number of Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan et al. [51] | 0.35 ± 0.12 | 167 | 0.40 ± 0.12 | 68 |

| Han et al. [52] | 0.22 ± 0.33 | 197 | 0.28 ± 0.12 | 60 |

| Lin et al. [40] | 0.19 ± 0.10 | 78 | 0.22 ± 0.14 | 108 |

| Qu et al. [41] | 0.22 ± 0.05 | 87 | 0.27 ± 0.11 | 51 |

| Trindade et al. [56] | 0.25 ± 0.08 | 37 | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 23 |

| Yang et al. [60] | 0.24 ± 0.06 | 48 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 16 |

| Zhang et al. [49] | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 60 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 60 |

| Liang et al. [53] * | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 76 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 183 |

| Lyu et al. [46] * | 0.2 ± 0.07 | 87 | 0.20 ± 0.09 | 49 |

| Sandra et al. [47] * | 0.20 ± 0.08 | 37 | 0.21 ± 0.07 | 38 |

| Yusufu et al. [44] * | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 30 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 30 |

| Zeng et al. [48] * | 0.23 ± 0.59 | 182 | 0.22 ± 0.86 | 102 |

| Study | D1 | D2 | D3 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan et al. [51] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Han et al. [52] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Kesarwani et al. [39] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Liang et al. [53] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Lin et al. [40] | Moderate/High | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Liu et al. [45] | Low | Low | Low/Moderate | Low |

| Lyu et al. [46] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Manchikanti et al. [54] | Moderate/High | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Mangoli et al. [59] | Moderate | Moderate | Low/Moderate | Low/Moderate |

| Qu et al. [41] | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Sandra et al. [47] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Stuard et al. [42] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Tóth et al. [55] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Trindade et al. [56] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Wu et al. [57] | Low/Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Yang et al. [43] | Low/Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Yu et al. [38] | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low/Moderate |

| Zeng et al. [48] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Zhang et al. [49] | Low | Moderate | Low | Low |

| Zhmud et al. [58] | High | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

| Zou et al. [50] | High | Moderate | Low | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ghenciu, D.M.; Dănilă, A.I.; Stoicescu, E.R.; Neagu, A.; Ghenciu, L.A. Tear Film Alterations in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243104

Ghenciu DM, Dănilă AI, Stoicescu ER, Neagu A, Ghenciu LA. Tear Film Alterations in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(24):3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243104

Chicago/Turabian StyleGhenciu, Delius Mario, Alexandra Ioana Dănilă, Emil Robert Stoicescu, Adrian Neagu, and Laura Andreea Ghenciu. 2025. "Tear Film Alterations in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Diagnostics 15, no. 24: 3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243104

APA StyleGhenciu, D. M., Dănilă, A. I., Stoicescu, E. R., Neagu, A., & Ghenciu, L. A. (2025). Tear Film Alterations in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics, 15(24), 3104. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15243104