Association Between Pneumoconiosis and Pleural Empyema: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

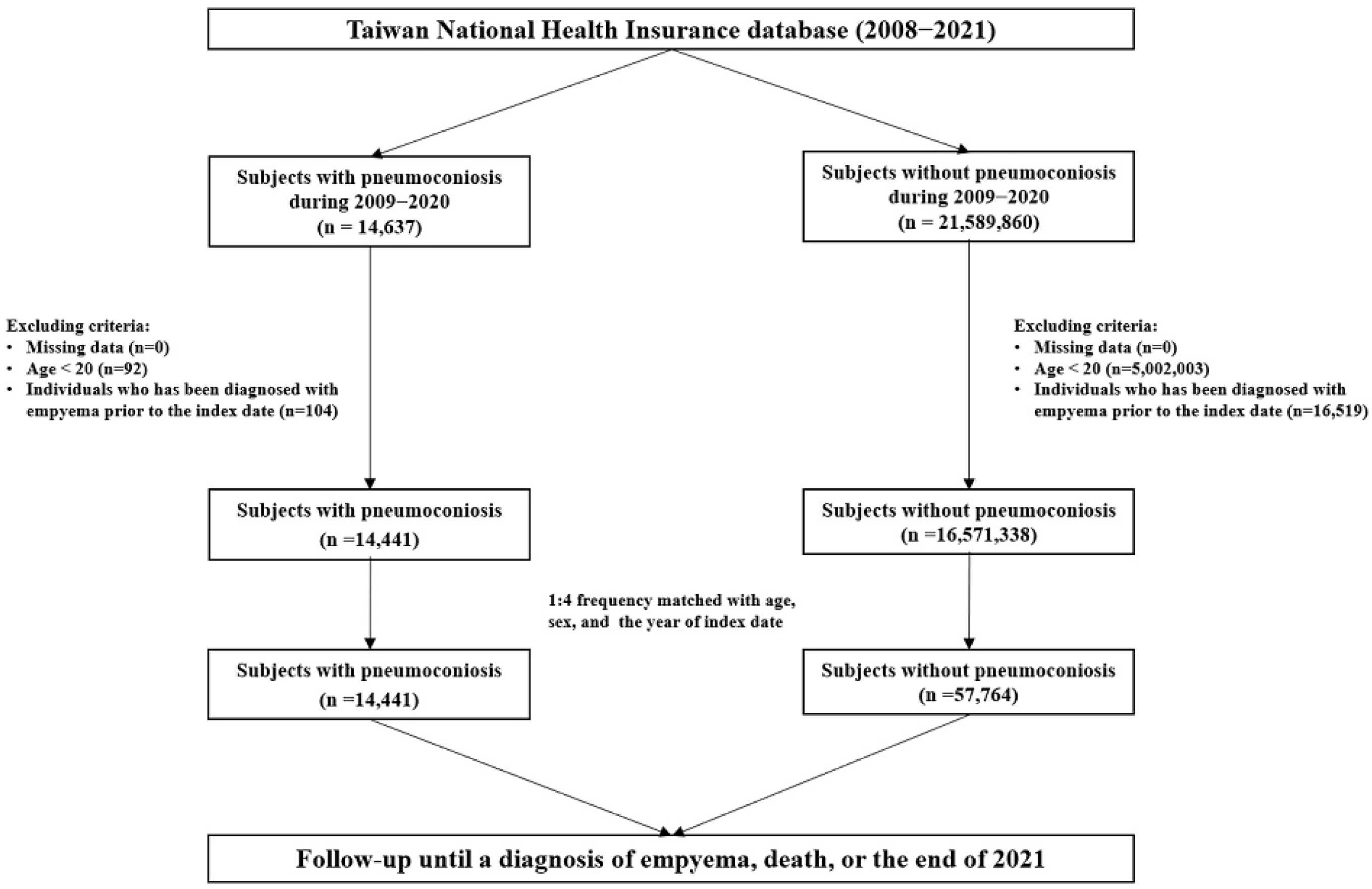

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Ethics and Consent

2.3. Case and Control Cohorts

2.4. Study Objectives and Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

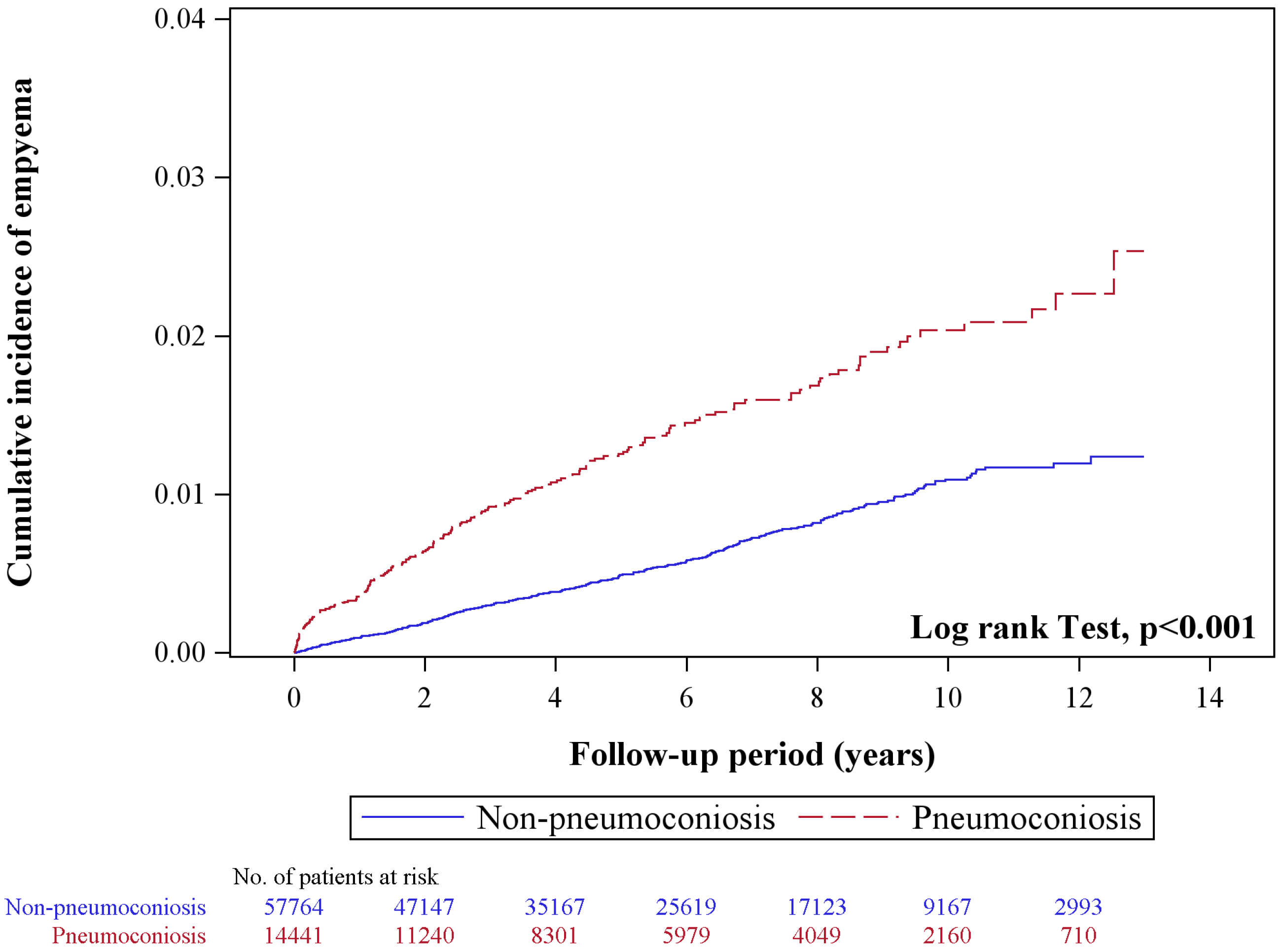

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qi, X.M.; Luo, Y.; Song, M.Y.; Liu, Y.; Shu, T.; Liu, Y.; Pang, J.-L.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Pneumoconiosis: Current status and future prospects. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 134, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, S.H. Occupational disease profile in Taiwan, Republic of China. Ind. Health 1994, 32, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liang, R.; Zhang, R.; Wang, B.; Cao, S.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, D.; Chen, W. Prevalence of coal worker’s pneumoconiosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, 29, 88690–88698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.Q.; Zhao, H.L.; Xie, Y. Progress in epidemiological studies on pneumoconiosis with comorbidities. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi 2021, 39, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.H.; Cheng, C.H.; Wang, C.L.; Dai, C.-Y.; Sheu, C.-C.; Tsai, M.-J.; Hung, J.-Y.; Chong, I.-W. Risk of pneumothorax in pneumoconiosis patients in Taiwan: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e054098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.M.; Lin, C.L.; Lin, M.C.; Chen, H.Y.; Lu, N.H.; Kao, C.H. Pneumoconiosis increases the risk of congestive heart failure: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Medicine 2016, 95, e3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.S.; Lin, C.L. Risk of atrial fibrillation in patients with pneumoconiosis: A nationwide study in Taiwan. Clin. Cardiol. 2020, 43, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.H.; Shen, T.C.; Chen, K.W.; Lin, C.-L.; Hsu, C.Y.; Wen, Y.-R.; Chang, K.-C. Risk of acute myocardial infarction in pneumoconiosis: Results from a retrospective cohort study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.H.; Lin, T.Y.; Huang, W.Y.; Chen, H.J.; Kao, C.H. Pneumoconiosis increases the risk of peripheral arterial disease: A nationwide population-based study. Medicine 2015, 94, e911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.Y.; Hsu, K.H.; Chen, Y.H.; Lin, C.-H. Increased risk of ischemic stroke in patients with pneumoconiosis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 22, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, C.S.; Ho, S.C.; Lin, C.L.; Lin, M.C.; Kao, C.H. Risk of cerebrovascular events in pneumoconiosis patients: A population-based study, 1996–2011. Medicine 2016, 95, e2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beggs, J.A.; Slavova, S.; Bunn, T.L. Patterns of pneumoconiosis mortality in Kentucky: Analysis of death certificate data. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2015, 58, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, N.B.; Blackley, D.J.; Halldin, C.N.; Laney, A.S. Current review of pneumoconiosis among US coal miners. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 6, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, R.; Adeyemi, O.; Arif, A.A. Estimating mortality from coal workers’ pneumoconiosis among Medicare beneficiaries with pneumoconiosis using binary regressions for spatially sparse data. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2022, 65, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, N.; Liu, C. Thoracic empyema: Aetiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2024, 30, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addala, D.N.; Bedawi, E.O.; Rahman, N.M. Parapneumonic Effusion and Empyema. Clin. Chest Med. 2021, 42, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Prele, C.M.; Brody, A.R.; Idell, S. Pathogenesis of pleural fibrosis. Respirology 2004, 9, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, H.; Honma, K.; Saito, Y.; Shida, H.; Morikubo, H.; Suganuma, N.; Fujioka, M. Pleural disease in silicosis: Pleural thickening, effusion, and invagination. Radiology 2005, 236, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caceres, J.D.; Venkata, A.N. Asbestos-associated pulmonary disease. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2023, 29, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.N.; Jerng, J.S.; Yu, C.J.; Yang, P.-C. Outcome of coal worker’s pneumoconiosis with acute respiratory failure. Chest 2004, 125, 1052–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salonen, J.; Purokivi, M.; Bloigu, R.; Kaarteenaho, R. Prognosis and causes of death of patients with acute exacerbation of fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2020, 7, e000563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayens, N.T.; Rayens, E.A.; Tighe, R.M. Co-occurrence of pneumoconiosis with COPD, pneumonia and lung cancer. Occup. Med. 2022, 72, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.H.; Li, C.H.; Shen, T.C.; Hung, Y.-T.; Tu, C.-Y.; Hsia, T.-C.; Hsu, W.-H.; Hsu, C.Y. Risk of chronic kidney disease in pneumoconiosis: Results from a retrospective cohort study (2008–2019). Biomedicines 2023, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.S.; Shen, T.C.; Lin, C.L.; Tu, C.-Y.; Hsia, T.-C.; Hsu, W.-H.; Cho, D.-Y. Risk of sleep disorders in patients with pneumoconiosis: A retrospective cohort study. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Liu, D.Y.; Hsu, H.L.; Yu, T.-L.; Yu, T.-S.; Shen, T.-C.; Tsai, F.-J. Risk of depression in patients with pneumoconiosis: A population-based retrospective cohort study. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 352, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.T.; Wei, T.; Huang, Y.L.; Wu, Y.P.; Chan, K.A. Validation of diagnosis codes in healthcare databases in Taiwan, a literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2023, 32, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redden, M.D.; Chin, T.Y.; van Driel, M.L. Surgical versus non-surgical management for pleural empyema. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 3, CD010651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller-Kopman, D.; Light, R. Pleural disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedawi, E.O.; Hassan, M.; Rahman, N.M. Recent developments in the management of pleural infection: A comprehensive review. Clin. Respir. J. 2018, 12, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashbaugh, D.G. Empyema thoracis. Factors influencing morbidity and mortality. Chest 1991, 99, 1162–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasley, P.B.; Albaum, M.N.; Li, Y.H.; Fuhrman, C.R.; Britton, C.A.; Marrie, T.J.; Singer, D.E.; Coley, C.M.; Kapoor, W.N.; Fine, M.J. Do pulmonary radiographic findings at presentation predict mortality in patients with community-acquired pneumonia? Arch. Intern. Med. 1996, 156, 2206–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menéndez, R.; Torres, A.; Zalacaín, R.; Aspa, J.; Villasclaras, J.J.M.; Borderías, L.; Moya, J.M.B.; Ruiz-Manzano, J.; de Castro, F.R.; Blanquer, J.; et al. Risk factors of treatment failure in community acquired pneumonia: Implications for disease outcome. Thorax 2004, 59, 960–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsing, A.W.; Ioannidis, J.P. Nationwide population science: Lessons from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015, 175, 1527–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.Y.; Su, C.C.; Shao, S.C.; Sung, S.-F.; Lin, S.-J.; Kao Yang, Y.-H.; Lai, E.C.-C. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database: Past and future. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 11, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pneumoconiosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| N = 57,764 | N = 14,441 | |||||

| n | % | n | % | p-Value † | SMD | |

| Age | >0.999 | |||||

| 20–64 | 20,928 | 36.2 | 5232 | 36.2 | <0.001 | |

| 65–74 | 17,276 | 29.9 | 4319 | 29.9 | <0.001 | |

| ≥75 | 19,560 | 33.9 | 4890 | 33.9 | <0.001 | |

| Mean ± SD | 67.8 | ±12.7 | 67.9 | ±12.6 | 0.476 | 0.007 |

| Gender | >0.999 | <0.001 | ||||

| Women | 8816 | 15.3 | 2204 | 15.3 | ||

| Men | 48,948 | 84.7 | 12,237 | 84.7 | ||

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Hypertension | 31,573 | 54.7 | 7401 | 51.3 | <0.001 | 0.068 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15,705 | 27.2 | 3174 | 22.0 | <0.001 | 0.121 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 19,624 | 34.0 | 4445 | 30.8 | <0.001 | 0.068 |

| HF | 4195 | 7.26 | 1444 | 10.0 | <0.001 | 0.098 |

| Asthma/COPD | 13,314 | 23.1 | 7010 | 48.5 | <0.001 | 0.552 |

| GERD | 8537 | 14.8 | 2734 | 18.9 | <0.001 | 0.111 |

| CLD | 8877 | 15.4 | 2466 | 17.1 | <0.001 | 0.046 |

| CKD | 4424 | 7.66 | 1016 | 7.04 | 0.011 | 0.024 |

| Rheumatic disease | 963 | 1.67 | 405 | 2.80 | <0.001 | 0.077 |

| Pneumothorax | 141 | 0.24 | 157 | 1.09 | <0.001 | 0.104 |

| Malignancy | 4909 | 8.50 | 1255 | 8.69 | 0.460 | 0.007 |

| Medication | ||||||

| Corticosteroid | 10,409 | 18.0 | 3916 | 27.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Healthcare utilization in the past year | ||||||

| Outpatient visits | <0.001 | |||||

| 0–14 | 26,019 | 45.0 | 4549 | 31.5 | 0.281 | |

| 15–28 | 16,444 | 28.5 | 4732 | 32.8 | 0.093 | |

| ≥29 | 15,301 | 26.5 | 5160 | 35.7 | 0.201 | |

| Mean ± SD | 21 | 18.4 | 26.3 | 19.8 | <0.001 | 0.278 |

| Inpatient admission | <0.001 | 0.713 | ||||

| 0 | 47,327 | 81.9 | 7240 | 50.1 | ||

| ≥1 | 10,437 | 18.1 | 7201 | 49.9 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 1.33 | <0.001 | 0.433 |

| Event | PY | Rate † | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR # (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumoconiosis | |||||

| No | 339 | 331,097 | 1.02 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Yes | 183 | 78,663 | 2.33 | 2.27 (1.89–2.71) *** | 1.79 (1.47–2.18) *** |

| Age | |||||

| 20–64 | 135 | 173,621 | 0.78 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 65–74 | 166 | 129,815 | 1.28 | 1.64 (1.31–2.06) *** | 1.38 (1.09–1.75) ** |

| ≥75 | 221 | 106,324 | 2.08 | 2.64 (2.13–3.28) *** | 1.96 (1.55–2.48) *** |

| Gender | |||||

| Women | 16 | 65,115 | 0.25 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| Men | 506 | 344,645 | 1.47 | 5.96 (3.63–9.81) *** | 5.12 (3.11–8.44) *** |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Hypertension | 291 | 200,916 | 1.45 | 1.29 (1.09–1.54) ** | 0.90 (0.74–1.10) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 149 | 92,534 | 1.61 | 1.35 (1.12–1.64) ** | 1.32 (1.07–1.63) ** |

| Hyperlipidemia | 145 | 128,937 | 1.12 | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) | 0.72 (0.58–0.89) *** |

| HF | 51 | 21,565 | 2.36 | 1.90 (1.42–2.54) *** | 1.07 (0.79–1.46) |

| Asthma/COPD | 210 | 96,483 | 2.18 | 2.16 (1.81–2.57) *** | 1.35 (1.11–1.65) ** |

| GERD | 74 | 52,623 | 1.41 | 1.10 (0.86–1.41) | 0.90 (0.69–1.16) |

| CLD | 78 | 55,984 | 1.39 | 1.09 (0.86–1.39) | 1.03 (0.80–1.32) |

| CKD | 58 | 20,066 | 2.89 | 2.37 (1.80–3.11) *** | 1.72 (1.28–2.29) *** |

| Rheumatic disease | 10 | 6357 | 1.57 | 1.22 (0.65–2.28) | 1.05 (0.56–1.98) |

| Pneumothorax | 5 | 1028 | 4.87 | 3.71 (1.54–8.96) ** | 1.82 (0.75–4.42) |

| Malignancy | 49 | 24,290 | 2.02 | 1.60 (1.20–2.16) ** | 1.19 (0.88–1.61) |

| Medication | |||||

| Corticosteroid | 130 | 62,381 | 2.08 | 1.81 (1.49–2.22) *** | 1.26 (1.01–1.57) * |

| Outpatient visits | |||||

| 0–14 | 186 | 187,349 | 0.99 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| 15–28 | 162 | 119,208 | 1.36 | 1.36 (1.10–1.68) ** | 1.01 (0.81–1.26) |

| ≥29 | 174 | 103,202 | 1.69 | 1.68 (1.37–2.07) *** | 0.98 (0.77–1.25) |

| Inpatient admission | |||||

| 0 | 333 | 335,120 | 0.99 | 1 (Reference) | 1 (Reference) |

| ≥1 | 189 | 74,640 | 2.53 | 2.51 (2.10–3.00) *** | 1.64 (1.34–2.00) *** |

| Pneumoconiosis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||||

| Event | PY | Rate † | Event | PY | Rate † | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR # (95% CI) | Interaction p | |

| Age | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 20–64 | 72 | 140,584 | 0.51 | 63 | 33,037 | 1.91 | 3.69 (2.63–5.18) *** | 2.57 (1.73–3.82) *** | |

| 65–74 | 109 | 104,331 | 1.04 | 57 | 25,484 | 2.24 | 2.14 (1.55–2.95) *** | 1.68 (1.19–2.38) ** | |

| ≥75 | 158 | 86,182 | 1.83 | 63 | 20,142 | 3.13 | 1.71 (1.27–2.29) *** | 1.39 (1.01–1.90) * | |

| Gender | 0.72 | ||||||||

| Women | 11 | 52,448 | 0.21 | 5 | 12,666 | 0.39 | 1.88 (0.65–5.41) | 1.46 (0.46–4.64) | |

| Men | 328 | 278,649 | 1.18 | 178 | 65,996 | 2.70 | 2.29 (1.91–2.74) *** | 1.80 (1.47–2.19) *** | |

| Comorbidity ‡ | <0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 69 | 103,167 | 0.67 | 46 | 17,431 | 2.64 | 3.94 (2.71–5.72) *** | 3.66 (2.52–5.31) *** | |

| Yes | 270 | 227,930 | 1.18 | 137 | 61,232 | 2.24 | 1.89 (1.54–2.32) *** | 1.89 (1.54–2.33) *** | |

| Corticosteroid | 0.539 | ||||||||

| No | 264 | 285,616 | 0.92 | 128 | 61,762 | 2.07 | 2.24 (1.81–2.77) *** | 1.88 (1.49–2.36) *** | |

| Yes | 75 | 45,481 | 1.65 | 55 | 16,901 | 3.25 | 1.98 (1.40–2.81) *** | 1.57 (1.08–2.29) * | |

| Outpatient visits | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 0–14 | 130 | 161,030 | 0.81 | 56 | 26,319 | 2.13 | 2.64 (1.93–3.61) *** | 2.10 (1.47–2.99) *** | |

| 15–28 | 100 | 92,893 | 1.08 | 62 | 26,315 | 2.36 | 2.19 (1.60–3.01) *** | 1.68 (1.19–2.38) ** | |

| ≥29 | 109 | 77,174 | 1.41 | 65 | 26,028 | 2.50 | 1.77 (1.30–2.41) *** | 1.49 (1.07–2.07) * | |

| Inpatient admission | 0.029 | ||||||||

| 0 | 246 | 287,905 | 0.85 | 87 | 47,215 | 1.84 | 2.14 (1.68–2.74) *** | 2.02 (1.57–2.61) *** | |

| ≥1 | 93 | 43,192 | 2.15 | 96 | 31,448 | 3.05 | 1.43 (1.07–1.90) * | 1.44 (1.06–1.95) * | |

| Pneumoconiosis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||||

| Event | PY | Rate † | Event | PY | Rate † | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR # (95% CI) | Interaction p | |

| Hypertension | 0.002 | ||||||||

| No | 131 | 167,457 | 0.78 | 100 | 41,386 | 2.42 | 3.07 (2.37–3.99) *** | 2.36 (1.76–3.16) *** | |

| Yes | 208 | 163,640 | 1.27 | 83 | 37,277 | 2.23 | 1.76 (1.36–2.26) *** | 1.42 (1.08–1.86) * | |

| Diabetes | 0.698 | ||||||||

| No | 234 | 253,505 | 0.92 | 139 | 63,720 | 2.18 | 2.35 (1.91–2.90) *** | 1.85 (1.47–2.33) *** | |

| Yes | 105 | 77,592 | 1.35 | 44 | 14,942 | 2.94 | 2.18 (1.53–3.09) *** | 1.59 (1.09–2.32) * | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.632 | ||||||||

| No | 244 | 225,107 | 1.08 | 133 | 55,716 | 2.39 | 2.20 (1.78–2.71) *** | 1.70 (1.35–2.15) *** | |

| Yes | 95 | 105,990 | 0.90 | 50 | 22,947 | 2.18 | 2.43 (1.72–3.42) *** | 1.99 (1.37–2.88) *** | |

| HF | 0.929 | ||||||||

| No | 310 | 315,118 | 0.98 | 161 | 73,077 | 2.20 | 2.24 (1.85–2.71) *** | 1.76 (1.43–2.17) *** | |

| Yes | 29 | 15,979 | 1.81 | 22 | 5,586 | 3.94 | 2.19 (1.26–3.81) ** | 2.06 (1.13–3.76) * | |

| Asthma/COPD | 0.105 | ||||||||

| No | 228 | 268,693 | 0.85 | 84 | 44,584 | 1.88 | 2.22 (1.73–2.85) *** | 1.96 (1.50–2.56) *** | |

| Yes | 111 | 62,404 | 1.78 | 99 | 34,079 | 2.91 | 1.65 (1.26–2.17) *** | 1.58 (1.19–2.11) ** | |

| GERD | 0.241 | ||||||||

| No | 291 | 290,960 | 1.00 | 157 | 66,177 | 2.37 | 2.37 (1.95–2.88) *** | 1.89 (1.53–2.34) *** | |

| Yes | 48 | 40,137 | 1.20 | 26 | 12,486 | 2.08 | 1.73 (1.08–2.80) * | 1.32 (0.79–2.21) | |

| CLD | 0.219 | ||||||||

| No | 286 | 287,145 | 1.00 | 158 | 66,630 | 2.37 | 2.38 (1.96–2.89) *** | 1.84 (1.49–2.28) *** | |

| Yes | 53 | 43,952 | 1.21 | 25 | 12,033 | 2.08 | 1.73 (1.07–2.78) * | 1.44 (0.86–2.41) | |

| CKD | 0.055 | ||||||||

| No | 294 | 314,705 | 0.93 | 170 | 74,988 | 2.27 | 2.42 (2.00–2.92) *** | 1.93 (1.57–2.38) *** | |

| Yes | 45 | 16,392 | 2.75 | 13 | 3675 | 3.54 | 1.29 (0.70–2.40) | 0.99 (0.52–1.89) | |

| Rheumatic Dz | 0.832 | ||||||||

| No | 334 | 326,509 | 1.02 | 178 | 76,894 | 2.31 | 2.26 (1.88–2.71) *** | 1.79 (1.47–2.18) *** | |

| Yes | 5 | 4588 | 1.09 | 5 | 1769 | 2.83 | 2.59 (0.75–8.96) | 1.75 (0.44–6.88) | |

| Pneumothorax | 0.953 | ||||||||

| No | 339 | 330,697 | 1.03 | 178 | 78,035 | 2.28 | 2.22 (1.85–2.66) *** | 1.77 (1.46–2.16) *** | |

| Yes | 0 | 400 | 0.00 | 5 | 628 | 7.97 | - | - | |

| Malignancy | 0.082 | ||||||||

| No | 303 | 312,042 | 0.97 | 170 | 73,428 | 2.32 | 2.38 (1.97–2.87) *** | 1.85 (1.51–2.28) *** | |

| Yes | 36 | 19,055 | 1.89 | 13 | 5235 | 2.48 | 1.34 (0.71–2.53) | 1.17 (0.59–2.33) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soh, K.-S.; Lin, C.-L.; Lee, W.-M.; Cho, D.-Y. Association Between Pneumoconiosis and Pleural Empyema: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233075

Soh K-S, Lin C-L, Lee W-M, Cho D-Y. Association Between Pneumoconiosis and Pleural Empyema: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233075

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoh, Khay-Seng, Cheng-Li Lin, Wei-Ming Lee, and Der-Yang Cho. 2025. "Association Between Pneumoconiosis and Pleural Empyema: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233075

APA StyleSoh, K.-S., Lin, C.-L., Lee, W.-M., & Cho, D.-Y. (2025). Association Between Pneumoconiosis and Pleural Empyema: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3075. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233075