A Comprehensive Review Comparing Artificial Intelligence and Clinical Diagnostic Approaches for Dry Eye Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Application of AI in Dry Eye Disease

2.1. ML for Dry Eye Disease Diagnosis

2.2. DL for Dry Eye Disease Diagnosis

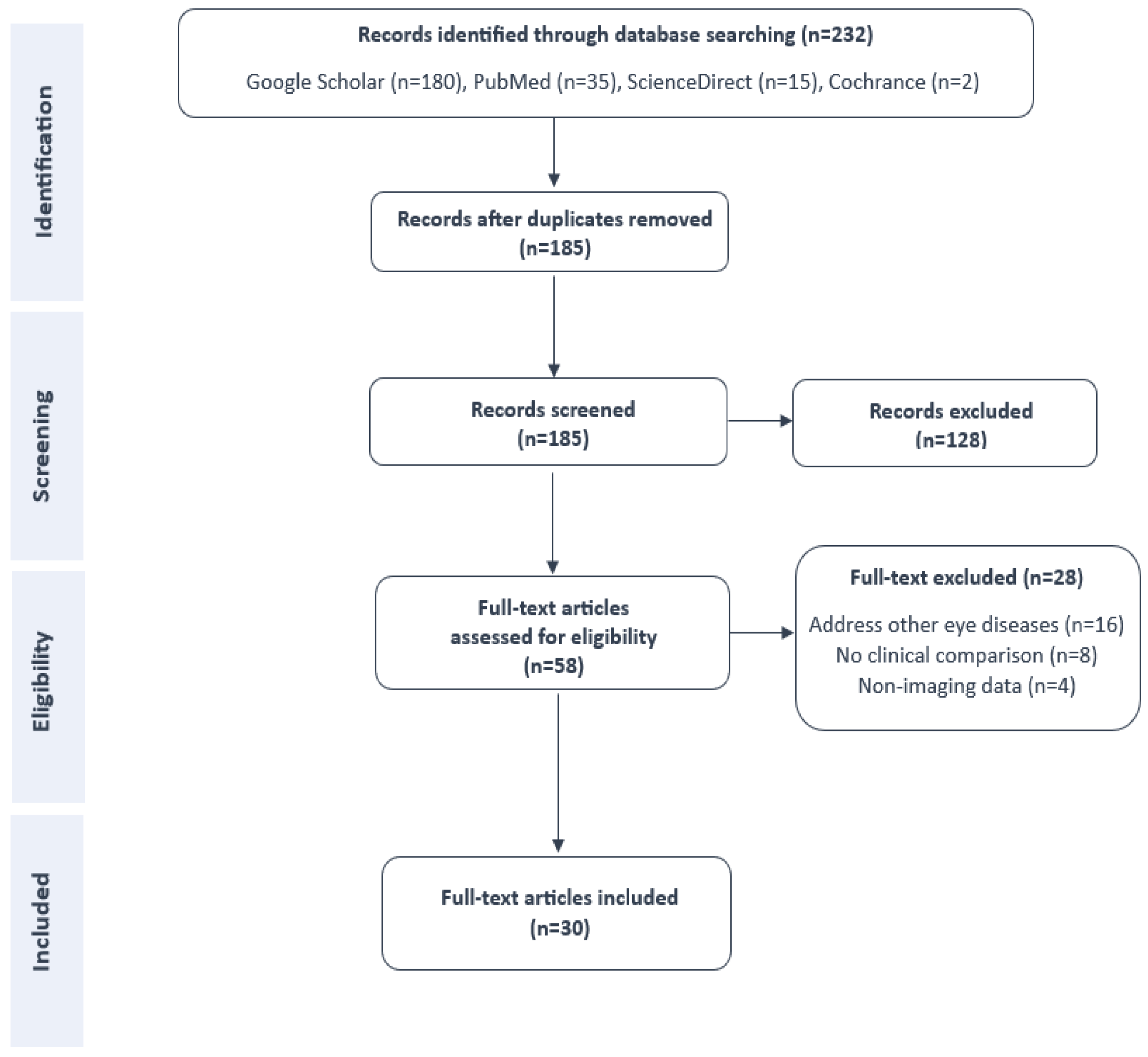

3. Methodology

3.1. Search Strategies

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Language and access: Full-text versions of the articles must be available in English.

- Clinical focus: The study must specifically address the use of artificial intelligence, including machine learning or deep learning methods, for the diagnosis or classification of dry eye disease.

- Descriptive completeness: Eligible studies were expected to provide the following:

- -

- The year of publication.

- -

- Details about the datasets used, including data acquisition and processing methods.

- -

- A clear description of the study approach and identification of the employed learning model.

- -

- An evaluation of model performance, including metrics such as accuracy, AUC, sensitivity, or specificity.

- -

- Analysis of the model’s correlation with clinical parameters (e.g., TBUT, Schirmer’s, staining, meibography).

- -

- A comparison of automatic DED diagnosis versus expert or clinician assessment.

- -

- A concise summary of study objectives and primary outcomes.

- The article was a review, editorial, or commentary rather than original research.

- The study focused on ocular anomalies unrelated to DED.

- The investigation did not include a performance comparison between AI-based and human diagnosis, or lacked sufficient methodological transparency for evaluation.

- Studies that relied on non-imaging modalities or questionnaire-based methods for DED diagnosis.

3.3. Data Extraction and Categorization

- (1)

- The year of publication: We recorded the publication year of each study to highlight the temporal evolution of artificial intelligence applications in DED diagnosis.

- (2)

- Study Purpose: We identified the objective or diagnostic task in each study by analyzing its abstract and introduction. This allowed us to classify the studies based on their focus, such as gland segmentation, tear film assessment, or subtype classification.

- (3)

- Learning Model: The reviewed studies employed a variety of artificial intelligence models, including machine learning algorithms (e.g., SVM, RF) and deep learning architectures (e.g., CNN, U-Net, GANs). We examined each model based on its architecture and configuration.

- (4)

- Data Source: We extracted information about each dataset, including the image modality (e.g., meibography, OCT, IVCM), sample size, training/test splits, and data acquisition tools. We also noted the dataset’s quality, diversity, and annotation methods, given their critical impact on model performance.

- (5)

- Development Strategy: We examined how each study structured its development pipeline, including preprocessing, training, validation, and testing procedures. We paid special attention to practices that enhance reproducibility, such as cross-validation, data augmentation, and external validation.

- (6)

- Correlation with Experts: We recorded whether the AI model’s performance was explicitly compared to clinical assessments by ophthalmologists or correlated with diagnostic parameters such as TBUT, Schirmer’s test, staining, or meiboscore.

- (7)

- Results: We reviewed each study’s diagnostic performance, focusing on reported metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and inter-expert agreement. We also emphasized whether the AI system outperformed or complemented human diagnosis.

- (8)

- Limitations: We highlighted reported limitations such as restricted dataset size, lack of external validation, overfitting risk, or limited translation into clinical practice, which point to opportunities for future work.

3.4. Assessment of Bias and Quality of Included Studies

4. Results

4.1. Videokeratography

4.2. Smartphone-Based Imaging

4.3. Tear Film Interferometry

4.4. Optical Coherence Tomography

4.5. Infrared Meibography

4.6. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy

4.7. Slit-Lamp Photography

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Analysis: AI Versus Clinical Diagnostic Methods

5.2. Limitations and Challenges

- Restricted scope and variability of training datasets: Most models were trained on monocentric datasets, typically using images from a single eye per patient and acquired using one imaging device or modality. This limited heterogeneity constraints’ generalizability. For example, Nejat et al. [42] developed a smartphone-based tear meniscus height measurement model using only images from iPhoneand Samsung devices. While the model achieved a high Dice coefficient (%), it lacked cross-device validation. Similarly, Wan et al. [49] reported a strong correlation with expert annotations () using Keratograph 5M images, yet the dataset consisted of only 305 samples from a single site. Even larger studies, such as the one by Graham et al. [58], which used 562 images from 363 subjects, applied exclusion criteria (e.g., prior surgery, inflammation), which may limit the applicability of results to the broader DED population. Moreover, few studies have evaluated model performance across different ethnic groups, imaging devices, or clinical settings, which limits confidence in their robustness for diverse real-world applications. Future work should prioritize multi-center, multi-ethnic, and cross-device datasets to ensure equitable and generalizable AI systems for DED diagnosis.

- Lack of external and cross-device validation: While many models demonstrated expert-level performance on internal test sets, their generalizability across clinical settings remains largely unverified. For instance, Feng et al. [68] trained SVM classifiers on 382 slit-lamp images from a single institution and reported AUCs up to %. Likewise, Saha et al. [57]’s meiboscore model performed well on internal data (% accuracy) but showed a marked drop on external datasets (%), underscoring the need for multi-center datasets and domain adaptation strategies.Although most studies in this review reported promising results, a large portion relied solely on internal validation without testing on external or real-world datasets. This limitation reduces the generalizability and clinical applicability of their findings, as models may overfit to specific imaging conditions or patient populations. Only a few studies incorporated external testing or multi-center data, highlighting the need for standardized validation protocols and real-world evaluation before clinical deployment. Recent works [8,72] have emphasized that external validation across diverse cohorts is essential to ensure robust and trustworthy AI tools for dry eye disease diagnosis.

- Annotation variability and quality of ground-truth labels: Few studies evaluated inter-rater reliability or the robustness of ground-truth annotations. Saha et al. [57] addressed this limitation by conducting six rounds of meiboscore labeling and assessing consistency using Cohen’s kappa and Bland–Altman analysis. Despite these efforts, 59 images were excluded due to artifacts or severe gland dropout. Similarly, Setu et al. [67] noted that even advanced DL models struggled with image artifacts such as poor contrast, defocus, and specular reflections—challenges not fully resolved by classical preprocessing methods.

- Lack of symptom-based or functional integration: Many studies focused exclusively on morphological features (e.g., gland tortuosity, nerve length), with limited inclusion of patient-reported outcomes or functional clinical tests such as TBUT or OSDI. Graham et al. [58] notably integrated imaging features with validated questionnaires and clinical signs, achieving predictive accuracy up to 99%. However, even in this case, the model lacked interpretability regarding feature contribution, highlighting the growing need for explainable AI (XAI) approaches.

- Impact of TFOS DEWS II Criteria Implementation Although the TFOS DEWS II framework establishes standardized diagnostic thresholds that combine subjective symptoms such as an OSDI score of ≥13 with at least one abnormal objective test, this review found that adherence to these criteria varied widely across the analyzed studies. Several works classified DED based on single-parameter evaluations such as meiboscore [57], tear meniscus height [42,47,49], or TBUT [50,52,66], while others relied solely on clinician judgment without specifying the use of TFOS DEWS II benchmarks. This heterogeneity in diagnostic definitions introduces label inconsistency, potentially biasing AI model performance and complicating cross-study comparisons. Consequently, high reported accuracy in some models may partly reflect dataset-specific labeling strategies rather than true diagnostic generalizability.

- Limited explainability and clinical interpretability: Most models operated as “black boxes,” providing limited insights into their internal decision-making processes—an issue that can undermine clinical trust, regulatory approval, and adoption. Only a few studies, such as the one by Yuan et al. [71], incorporated interpretability tools such as heatmaps and lesion-aware visualization to highlight key diagnostic regions. However, the systematic evaluation of model explainability remains scarce. Broader implementation of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques—such as saliency mapping [76], Grad-CAM visualization [77], and attention mechanisms [78]—is essential to bridge the gap between high algorithmic performance and clinical confidence, ensuring transparency, reproducibility, and safer AI integration in ophthalmic practice.

5.3. Recommendations and Future Perspectives

- Establish centralized, multimodal, publicly available datasets: None of the reviewed studies utilized open-access datasets. Most relied on data collected at single institutions under controlled conditions. For instance, Setu et al. [67] and Saha et al. [57] employed internal meibography datasets, while Nejat et al. [42] trained their model using images from only two smartphone types. Such limited scope restricts model generalizability across devices and populations. Future initiatives should prioritize the creation of standardized, multi-center datasets incorporating various imaging modalities (e.g., RGB, infrared, OCT), along with corresponding clinical metrics and symptom-based data.Precedents from other medical domains underscore the feasibility and benefits of this approach. The Brain Tumor Segmentation Challenge (BraTS) 2018 dataset [79], for example, aggregated multimodal Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans from 19 institutions, while the Ophthalmologie Diabète Télémédecine (OPHDIAT) telemedicine network [80,81] facilitated diabetic retinopathy screening across 16 centers. Similar efforts in DED could greatly enhance reproducibility, support benchmarking, and improve model robustness.

- Utilize data augmentation to address dataset limitations: Data augmentation remains an effective strategy for improving data diversity and mitigating class imbalance. Common techniques—such as flipping, rotation, intensity perturbation, and elastic deformation—have consistently enhanced model performance in DED applications. For example, Feng et al. [68] and Zheng et al. [46] employed DA to improve segmentation outcomes, while Nejat et al. [42]’s preprocessing and fusion pipeline increased TMH estimation accuracy to %. In other domains, DA has been shown to improve prostate segmentation accuracy by 12–47% and to strengthen brain tumor classification using class-balanced learning strategies [82,83].

- Prioritize model interpretability and clinical transparency: Explainable AI should be embedded into model development from the outset. Beyond high performance, clinical deployment demands that models offer interpretable outputs. Techniques such as class activation mapping (CAM), attention mechanisms, and symbolic reasoning can enhance transparency and foster trust. For example, Jiang et al. [84] used CAMs to highlight diabetic retinopathy features, while Gwenolé et al. [22] introduced “ExplAIn,” an interpretable AI framework that visualized relevant image regions to support physician decision-making.

5.4. Theoretical Implications

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, H.; McCann, P.; Lien, T.; Xiao, M.; Abraham, A.G.; Gregory, D.G.; Hauswirth, S.G.; Qureshi, R.; Liu, S.-H.; Saldanha, I.J.; et al. Prevalence of dry eye and Meibomian gland dysfunction in Central and South America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicnesh, J.; Oh, S.L.; Wei, J.K.E.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Chua, K.C.; Tong, L.; Acharya, U.R. Thoughts concerning the application of thermogram images for automated diagnosis of Dry Eye—A review. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2020, 106, 1350–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.; Donaldson, K.E.; Nichols, K.K.; MacIver, S.; Gupta, P.K. Dry eye disease: Consideration for women’s health. J. Women’s Health 2019, 28, 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, F.; Alves, M.; Bunya, V.Y.; Jalbert, I.; Lekhanont, K.; Malet, F.; Na, K.-S.; Schaumberg, D.; Uchino, M.; Vehof, J.; et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 334–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akowuah, P.K.; Kobia-Acquah, E. Prevalence of dry eye disease in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2020, 97, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell, J.T.; Idarraga, M.; Kumar, N.; Galor, A. Impact of air pollution and weather on Dry Eye. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.J.; Ziegler, C.; Mitchell, G.L.; Nichols, K.K. Self-reported dry eye disease across refractive modalities. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005, 46, 1911–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storås, A.M.; Strümke, I.; Riegler, M.A.; Grauslund, J.; Hammer, H.L.; Yazidi, A.; Halvorsen, P.; Gundersen, K.G.; Utheim, T.P.; Jackson, C.J. Artificial Intelligence in dry eye disease. Ocul. Surf. 2022, 23, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeev, M.S.; Miller, D.D.; Latkany, R. Diagnosis of dry eye disease and emerging technologies. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2014, 8, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phadatare, S.P.; Momin, M.; Nighojkar, P.; Askarkar, S.; Singh, K.K. A comprehensive review on dry eye disease: Diagnosis, medical management, recent developments, and future challenges. Adv. Pharm. 2015, 2015, 704946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dry Eye WorkShop Group. The definition and classification of dry eye disease: Report of the definition and classification subcommittee of the International Dry Eye Workshop. Ocul. Surf. 2007, 5, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolffsohn, J.S.; Arita, R.; Chalmers, R.; Djalilian, A.; Dogru, M.; Dumbleton, K.; Gupta, P.K.; Karpecki, P.; Lazreg, S.; Pult, H.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 539–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.P.; Nichols, K.K.; Akpek, E.K.; Caffery, B.; Dua, H.S.; Joo, C.-K.; Liu, Z.; Nelson, J.D.; Nichols, J.J.; Tsubota, K.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubota, K.; Kato, H.; Nakano, T.; Nishida, T.; Shimazaki, J.; Uchino, M.; Chikuda, M.; Kinoshita, S.; Hyon, J.Y.; The Asia Dry Eye Society Members. Asia Dry Eye Society consensus: Redefining dry eye disease for Asia. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 82, 100751. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley, J.D.; Russakoff, D.B.; McCarron, M.E.; Weinberg, R.L.; Izzi, J.M.; Misra, S.L.; McGhee, C.N.; Mankowski, J.L. Deep learning-based analysis of macaque corneal sub-basal nerve fibers in confocal microscopy images. Eye Vis. 2020, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yeh, T.N.; Chakraborty, R.; Yu, S.X.; Lin, M.C. A deep learning approach for meibomian gland atrophy evaluation in meibography images. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekala, M.J.; Joshi, N.; Liu, T.Y.A.; Bressler, N.M.; DeBuc, D.C.; Burlina, P. Deep Learning based retinal OCT segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2019, 114, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.K.; Chowdhury, A.M.; Na, K.-S.; Hwang, G.D.; Eom, Y.; Kim, J.; Jeon, H.-G.; Hwang, H.S.; Chung, E. Automated quantification of meibomian gland dropout in infrared meibography using Deep Learning. Ocul. Surf. 2022, 26, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Taheri, S.; Dunshea, F.; Leury, B.; DiGiacomo, K.; Osei-Amponsah, R.; Brodie, G.; Chauhan, S. Non-invasive measure of heat stress in sheep using machine learning techniques and infrared thermography. Small Rumin. Res. 2022, 207, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, N.; Shih, A.K.Y.; Lin, C.; Kuo, M.T.; Hwang, Y.S.; Wu, W.C.; Kuo, C.F.; Kang, E.Y.C.; Hsiao, C.H. Using slitlamp images for deep learning-based identification of bacterial and fungal keratitis: Model development and validation with different convolutional neural networks. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedidya, T.; Hartley, R.; Guillon, J.P.; Kanagasingam, Y. Automatic Dry Eye Detection. In Proceedings of the Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI (2007), Brisbane, Australia, 29 October–2 November 2007; pp. 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quellec, G.; Al Hajj, H.; Lamard, M.; Conze, P.-H.; Massin, P.; Cochener, B. Explain: Explanatory artificial intelligence for diabetic retinopathy diagnosis. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 72, 1361–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.-Y.; Liu, Z.-Y.; Chen, D.-Y. Tear film break-up time measurement using deep convolutional neural networks for screening dry eye disease. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 6857–6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with Deep Neural Networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorj, U.; Lee, K.-K.; Choi, J.-Y.; Lee, M. The skin cancer classification using deep convolutional Neural Network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 9909–9924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, W.; Ahmed, S.; Tahir, A.; Khan, H.A. Classification of breast cancer histology images using AlexNet. In Image Analysis and Recognition; Campilho, A., Karray, F., Romeny, B.t.H., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmoufidi, A.; Fahssi, K.E.; Jai-Andaloussi, S.; Sekkaki, A. Automatically density-based breast segmentation for mammograms by using dynamic K-means algorithm and Seed Based Region Growing. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Pisa, Italy, 11–14 May 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfan, T.H.; Hayaty, M.; Hadinegoro, A. Classification of brain tumour types based on MRI images using MobileNet. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Innovative and Creative Information Technology (ICITech), Salatiga, Indonesia, 23–25 September 2021; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umer, M.J.; Sharif, M.; Raza, M.; Kadry, S. A deep feature fusion and selection-based retinal eye disease detection from OCT images. Expert Syst. 2023, 40, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.M.; Lee, Y.C.; Kim, J.H. Explanatory model of dry eye disease using health and nutrition examinations: Machine learning and network-based factor analysis from a national survey. Jmir Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e16153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amouei Sheshkal, S.; Gundersen, M.; Alexander Riegler, M.; Aass Utheim, Ø.; Gunnar Gundersen, K.; Rootwelt, H.; Prestø Elgstøen, K.B.; Lewi Hammer, H. Classifying dry eye disease patients from healthy controls using machine learning and metabolomics data. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarada, T.N.; Al-Ani, M.; Choueiry, R.M. Machine learning models for the diagnosis of dry eyes using real-world clinical data. Touch Ophthalmol. 2024, 18, 34–40. Available online: https://touchophthalmology.com/ocular-surface-disease/journal-articles/machine-learning-models-for-the-diagnosis-of-dry-eyes-using-real-world-clinical-data/ (accessed on 28 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Hagan, J.D.W.; Ahmed, K. Non-invasive dry eye disease detection using in-frared thermography images: A proof-of-concept study. Diagnostics 2024, 15, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprowski, R.; Tian, L.; Olczyk, P. A clinical utility assessment of the automatic measurement method of the quality of Meibomian glands. Biomed. Eng. Online 2017, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, A.; Eleiwa, T.; Chase, C.; Ozcan, E.; Tolba, M.; Feuer, W.; Abdel-Mottaleb, M.; Shousha, M.A. Multidisease deep learning neural network for the diagnosis of corneal diseases. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 226, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. CVPR 2016, 2016, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Wen, H.; Bai, F.; Huang, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Pu, Y.; Le, Z.; Gong, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Comparison of deep learning-assisted blinking analysis system and Lipiview interferometer in dry eye patients: A cross-sectional study. Eye Vis. 2024, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.; Sterne, J.A.; Bossuyt, P.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, N.; Kusada, N.; Kato, H.; Furusawa, Y.; Sotozono, C.; Georgiev, G.A. Dry eye subtype classification using videokeratography and deep learning. Diagnostics 2023, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejat, F.; Eghtedari, S.; Alimoradi, F. Next-Generation Tear Meniscus Height Detecting and Measuring Smartphone-Based Deep Learning Algorithm Leads in Dry Eye Management. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2024, 4, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks. CVPR 2018, 2018, 4510–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.D.; Hamm, A.; Bensinger, E.; Kerti, S.J.; Gomes, P.J.; Ousler, G.W.; Gupta, P.; De Moraes, C.G.; Abelson, M.B. Statistical Evaluation of Smartphone-Based Automated Grading System for Ocular Redness Associated with Dry Eye Disease and Implications for Clinical Trials. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 19, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. ECCV 2018, 2018, 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, L.; Wen, H.; Ren, Y.; Huang, S.; Bai, F.; Li, N.; Craig, J.P.; Tong, L.; Chen, W. Impact of incomplete Blinking Analyzed Using a Deep Learning Model with the Keratograph 5M in Dry Eye Disease. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, W.; Rong, H.; Hei, K.; Liu, G.; He, M.; Du, B.; Wei, R.; Zhang, Y. A deep learning-assisted automatic measurement of tear meniscus height on ocular surface images and its application in myopia control. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2025, 13, 1554432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. ICCV 2017, 2017, 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Hua, R.; Guo, P.; Lin, P.; Wang, J.; Yang, W.; Hong, X. Measurement method of tear meniscus height based on deep learning. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1126754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, C.; Elsawy, A.; Eleiwa, T.; Ozcan, E.; Tolba, M.; Shousha, M.A. Comparison of autonomous as-Oct deep learning algorithm and clinical dry eye tests in diagnosis of Dry Eye disease. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2021, 15, 4281–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, C.; Bai, J.; Murakami, D.; Young, J.; Cheng, D.; Gupta, P.; Claypool, C.; Holl, E.; Kading, D.; Hauser, W.; et al. Internal validation of a convolutional neural network pipeline for assessing meibomian gland structure from meibography. Optom. Vis. Sci. Off. Publ. Am. Acad. Optom. 2025, 102, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Liu, X.; Lin, X.; Fu, Y.; Chen, C.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Liu, M.; Yang, W.; et al. A Novel Meibomian Gland Morphology Analytic System Based on a Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 23083–23094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, F.; Wei, S.; Li, X. A Deep Learning Model for Evaluating Meibomian Glands Morphology from Meibography. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, A.B.L.; Sønderby, S.K.; Larochelle, H.; Winther, O. Autoencoding beyond pixels using a learned similarity metric. ICML 2016, 2016, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, M.; Zhou, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wu, L.; Zheng, H.; Yang, Y. Automatic identification of meibomian gland dysfunction with meibography images using deep learning. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 42, 3275–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setu, M.A.K.; Horstmann, J.; Schmidt, S.; Stern, M.E.; Steven, P. Deep learning-based automatic meibomian gland segmentation and morphology assessment in infrared meibography. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.K.; Chowdhury, A.M.M.; Na, K.-S.; Hwang, G.D.; Eom, Y.; Kim, J.; Jeon, H.-G.; Hwang, H.S.; Chung, E. AI-based automated Meibomian gland segmentation, classification and reflection correction in infrared Meibography. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.15543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.D.; Kothapalli, T.; Wang, J.; Ding, J.; Tse, V.; Asbell, P.A.; Yu, S.X.; Lin, M.C. A machine learning approach to predicting dry eye-related signs, symptoms and diagnoses from meibography images. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S.; Ponnan, S. Author Correction: An efficient enhanced stacked auto encoder assisted optimized deep neural network for forecasting Dry Eye Disease. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2018, 11045, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, S.M.; Chakiat, A.; S, S.; Vunnava, K.P.; Shetty, R. Deep learning segmentation and quantification of Meibomian glands. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2020, 57, 101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Shi, W.Q.; Liao, X.L.; Su, T.; Liang, R.B.; Li, Q.Y.; Ge, Q.M.; Shu, H.Y.; et al. Detection of meibomian gland dysfunction by in vivo confocal microscopy based on deep convolutional neural network. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Y.; Zhao, H.; Lin, J.-Y.; Wu, S.-N.; Liu, X.-W.; Zhang, H.-D.; Shao, Y.; Yang, W.-F. Artificial intelligence to detect meibomian gland dysfunction from in-vivo laser confocal microscopy. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 774344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Shi, F.; Wang, Y.; Chou, Y.; Li, X. A Deep Learning Model for Automated Sub-Basal Corneal Nerve Segmentation and Evaluation Using In Vivo Confocal Microscopy. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, E.; Arslan, A.T.; Yildiz Tas, A.; Acer, A.F.; Demir, S.; Sahin, A.; Erol Barkana, D. Generative Adversarial Network Based Automatic Segmentation of Corneal Subbasal Nerves on In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Images. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Xie, J.; Yang, T.; Su, P.; Liu, R.; Sun, T.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Feng, X.; Ma, S.; et al. Quantification of increased corneal subbasal nerve tortuosity in dry eye disease and its correlation with clinical parameters. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2021, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setu, M.A.K.; Schmidt, S.; Musial, G.; Stern, M.E.; Steven, P. Segmentation and Evaluation of Corneal Nerves and Dendritic Cells From In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Images Using Deep Learning. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Ren, Z.K.; Wang, K.N.; Guo, H.; Hao, Y.R.; Shu, Y.C.; Tian, L.; Zhou, G.Q.; Jie, Y. An Automated Grading System Based on Topological Features for the Evaluation of Corneal Fluorescein Staining in Dry Eye Disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourukmas, R.; Roth, M.; Geerling, G. Automated vs. human evaluation of corneal staining. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 2605–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, D.; Shin, Y.; Kim, M.K.; Jeon, H.S.; Kim, Y.G.; Yoon, C.H. Deep learning-based fully automated grading system for dry eye disease severity. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Deng, Y.; Cheng, P.; Xu, R.; Ling, L.; Xue, H.; Zhou, S.; Huang, Y.; Lyu, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Revolutionizing corneal staining assessment: Advanced evaluation through lesion-aware fine-grained knowledge distillation. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, E.; Ishikawa, T.; Tanji, M.; Agata, N.; Nakayama, S.; Nakahara, Y.; Yokoiwa, R.; Sato, S.; Hanyuda, A.; Ogawa, Y.; et al. Artificial intelligence to estimate the tear film breakup time and diagnose dry eye disease. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Barche, F.Z.; Benyoussef, A.A.; El Habib Daho, M.; Lamard, A.; Quellec, G.; Cochener, B.; Lamard, M. Automated tear film break-up time measurement for dry eye diagnosis using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.-Y.; Ting, P.-J.; Chang, S.-W.; Chen, D.-Y. Superficial punctate keratitis grading for dry eye screening using deep convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 1672–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chiu, P.W.; Tam, V.; Lee, A.; Lam, E.Y. Dual-Mode Imaging System for Early Detection and Monitoring of Ocular Surface Diseases. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2024, 18, 783–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Murakami, T.; Ishihara, K.; Mori, Y.; Tsujikawa, A. Explainable Artificial Intelli-gence-Assisted Exploration of Clinically Significant Diabetic Retinal Neurodegeneration on OCT Images. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2025, 5, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Son, J.; Shin, J.Y.; Kim, H.D.; Jung, K.H.; Park, K.H. Development and validation of deep learning models for screening referable diabetic retinopathy using Grad-CAM visualization. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 104, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karn, P.K.; Abdulla, W.H. Advancing Ocular Imaging: A Hybrid Attention Mechanism-Based U-Net Model for Precise Segmentation of Sub-Retinal Layers in OCT Images. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, W.; Milletarì, F.; Xu, D.; Rieke, N.; Hancox, J.; Zhu, W.; Baust, M.; Cheng, Y.; Ourselin, S.; Cardoso, M.J.; et al. Machine Learning in Medical Imaging. arXiv 2019. arXiv.1910.00962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massin, P.; Chabouis, A.; Erginay, A.; Viens-Bitker, C.; Lecleire-Collet, A.; Meas, T.; Guillausseau, P.-J.; Choupot, G.; André, B.; Denormandie, P. Ophdiat©: A Telemedical network screening system for diabetic retinopathy in the île-de-france. Diabetes Metab. 2008, 34, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matta, S.; Lamard, M.; Conze, P.-H.; Le Guilcher, A.; Ricquebourg, V.; Benyoussef, A.-A.; Massin, P.; Rottier, J.-B.; Cochener, B.; Quellec, G. Automatic screening for ocular anomalies using fundus photographs. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2021, 99, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Sanford, T.; Harmon, S.; Turkbey, B.; Wood, B.J.; Roth, H.; Myronenko, A.; Xu, D.; et al. Generalizing Deep Learning for Medical Image Segmentation to Unseen Domains via Deep Stacked Transformation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2020, 39, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Meng, Z.; Wei, L.; Sun, C.; Zou, Q.; Su, R. Supervised brain tumor segmentation based on gradient and context-sensitive features. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongyang, J.; Yang, K.; Gao, M.; Zhang, D.; Ma, H.; Qian, W. An interpretable ensemble deep learning model for diabetic retinopa-thy disease classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 July 2019; pp. 2045–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Ref. | Year | Purpose | Learning Model | Data Source | Development Strategy | Correlation with Experts | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [41] | 2023 | DED subtype classification. | 3D-CNN | - 243 eyes; (31 sADDE; 73 mADDE; 84 DWDE;55 IEDE). | - Training (146 cases); - Test (97 cases); - DA (training = 2628 cases); - TFOD labeling. | - Strong correlation with TFOD-based subtypes, with highest accuracy in sADDE (). | - Accuracy: ; - sADDE %; - mADDE %; - DWDE %; - IEDE %. | - Unequal class distribution; - High diagnostic complexity. |

| Study Ref. | Year | Purpose | Learning Model | Data Source | Development Strategy | Correlation with Experts | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [42] | 2024 | TMH via smartphone. | U-Net + MobileNetV2. | - 1021 images (734 patients). | - Segmentation; - Cropping; - Super-resolution; - TMH calculation from light reflection. | - Matched iris diameter and pixel metrics vs. manual. | - Dice coefficient: ; - Overall accuracy: . | - Reflectivity may vary across devices. |

| [44] | 2025 | Grading conjunctival hyperemia. | DeepLabV3 + LR. | - 29,640 images (450 DED patients). | - Segment the conjunctiva; - Predict redness grade; - Data split: training , validation 20%. | - MAE of , strong alignment with expert scoring. | - of predictions within 1 unit of the expert mean grade. | - Limited feature space; - Trial-specific protocols. |

| Study Ref. | Year | Purpose | Learning Model | Data Source | Development Strategy | Correlation with Experts | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | 2022 | Incomplete blinking detection. | U-Net CNN | - 1019 video frames (100 subjects). | - Resizing to 512 × 512; - 80/10/10 split; - DA (flipping, rotation, translation, and scaling); - 100 epochs with early stopping. | IB frequency correlated with - TMH (R = ); - NIBUT (R = ); - TO (R = ); - CLGS (R = ); - OSDI (R = ); - All . | - Dice = ; - IoU = ; - Sensitivity = for 30 FPS videos; - IB frequency higher in DED (). | - Slightly lower accuracy with 30 FPS; - Only 30 FPS and 8 FPS videos were tested. |

| [47] | 2025 | Automatic TMH measurement. | Mask R-CNN (ResNet-101) | - 1200 OSIs (100 external validation). | - 70/20/10 split; - 200 epochs. | - R2 = vs. expert. | - IoU: ; - AUC: . | - Limited sample size; - Same device/same center; - No other clinical factors. |

| [49] | 2023 | TMH measurement. | DeepLabv3 + ResNet50 + GoogleNet + FCN. | - 305 OSIs. | - CNN segmentation; - Region detection (CCPR); - TMH quantification with regression. | - r2 = vs. manual. | - Dice = ; - Sensitivity = . | - Moderate sample size; - Relies on static image quality. |

| Study Ref. | Year | Purpose | Learning Model | Data Source | Development Strategy | Correlation with Experts | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [50] | 2021 | Compare DL to clinical tests (AS-OCT). | VGG19 | - 27,180 AS-OCT Images (151 eyes). | - Exclude poor quality images; - 14,294 training; - 3574 validation; - 7020 test. | - Significant agreement with CFS, CLGS, Schirmer; - No correlation with TBUT, OSDI . | - Accuracy %; - Sensitivity %; - Specificity %. | - No gold standard; - Same device and same center; - Limited dataset. |

| Study Ref. | Year | Purpose | Learning Model | Data Source | Development Strategy | Correlation with Experts | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [51] | 2025 | Standardize MG absence detection. | 3 CNN: (IQD, OFD, GAD) | - 143,476 meibography (15 sites); - 135,251 after cleaning. | -80/10/10 split. - Class balancing for IQD/OFD; - Data annotation. | - Cohen’s : 0.60–0.71. | IQD: - AUROC = ; - Precision = . OFD: - AUROC = ; - Precision = . GAD: - AUROC = ; - Precision = . | - No external validation; - Limited interpretability. |

| [52] | 2021 | Assess MG morphology + clinical link. | Mini U-Net CNN. | - 120 Meibography images. | - Preprocess; - DA; - Data split (120 epochs). | - Correlated with clinical metrics; - Repeatability = . | - IoU: . - Processing time: 100 ms/image. | - Small sample size; - Minor accuracy gain but 10× more parameters. |

| [53] | 2023 | MG + tarsus segmentation. | - ResNet18; - U-Net + ResNet34;VAE-GAN. | - 1087 images (366 DED patients). | - 70/20/10 split; - Preprocessing: Cropping, bilateral filtering, max-min normalization. - DA: Color jittering, random lighting, horizontal flips, Gaussian noise. | - Strong agreement with experts (TS); MGS sens 75%. | TS: - AUC = ; - Accuracy = . MGS: - AUC = ; - Accuracy = . | - Single-device data; - No symptom link; - Moderate sensitivity. |

| [55] | 2022 | MG loss quantification. | R-CNN | - 1878 images (475 patients). | - 80/20 split; - Independent test (58 images); - Preprocessing. | -; - Mean difference = . | - ; - VL . | - Single-center; - Small sample size; - No external validation. |

| [56] | 2021 | MG segmentation + assessment. | Inception ResNet + U-net | - 728 images. | - Data annotation; - Data preparation; - Design & training; - Model evaluation; - Training & validation (628); - Testing (100 images). | - Similar to manual . | - 100% repeatability; - Segmentation time = s per image - Accuracy = 84% | -Device specific; -Partial segmentation success. |

| [57] | 2022 | Segment MG + eyelids, estimate meiboscore, remove reflections. | - ResNet34-based encoder-decoder; - Custom CNN; - GAN. | - 1000 images; - External Test (600 images). | - Annotation; - 200 epochs; - DA: Shear, horizontal flip (). | - meiboscore agreement; - k = − . | IQD: -AUROC = ; Precision = . OFD: AUROC = ; Precision = . GAD: AUROC = ; Precision = . | - Internal validation only; - Device specific. |

| [58] | 2024 | Predict DED signs, symptoms, diagnosis from MG morphology. | Supervised segmentation + LR. | - 562 images (363 subjects). | - Data annotation; - Preprocessing; - Feature selection; - 5-fold CV. | - Compared to expert labels. | - Signs: Accuracy 72.6–99.1% - Symptoms: Accuracy 60.7–86.5% - Diagnoses: Accuracy 73.7–85.2% | - Lower accuracy for symptom; - Single-center dataset. |

| [59] | 2025 | Early DED detection & classification. | - UNet++; - ESAE; - SLSTM-STSA; - EQBFOA. | - 1000 MG images (320 patients). | Multi-stage pipeline: - UNet++ segmentation; - COFA; - Optimization with EQBFOA; - Classification with SLSTMSTSA. | - High agreement in classification. | - % accuracy (SL-FRST). | - Computationally intensive; - Requires real-time testing. |

| [61] | 2020 | Segment + quantify MG. | CNN19 | - 400 Hand-held; - 400 Keratograph images. | - DA using ET and P; - Gland segmentation; - Metrics computation; - Training 600; - Testing 200. | The p-values vs. ground-truth. | For diseased cases: - Nbr of glands =; - Tortuosity = ; - Width = ; - Length = ; - Gland-drop = . | - Limited sample size. |

| Study Ref. | Year | Purpose | Learning Model | Data Source | Development Strategy | Correlation with Experts | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [62] | 2021 | MGD Detection. | ResNet 34 | - 24,919 images (NG = 2896, NMGOG = 830, MGAG = 3585, MGAOG = 1745, MGOG = 3086, MGOOG = 488). | - Extract features; classify images; - Data split: 70/30; - 12,889 evaluation. | - High agreement with the experts. | - Accuracy –%; - AUROCs . | - Single architecture; - South China data only. |

| [63] | 2021 | Classification of MGD types. | DenseNet169 | - 8311 VLCMI images (Healthy = 2766 OMGD = 2744 AMGD = 2801). | - Exclude poor quality images; - Train DenseNet121, DenseNet169, DenseNet201; - Data split: 60/40. | - Expert accuracy 91%. | - DenseNet169: 97% OMGD, 99% AMGD and 98% healthy. | - Only 2 structural abnormalities of MG; - Single-center. |

| [64] | 2020 | Automated CNF segmentation/evaluation. | CNS-Net | - 691 IVCM images (104 patients). | - Training (483); - Validation (69); - Test (139); - DA: Flipping, rotation, PCA noise. | - AUC: ; - mAP: ; Bland–Altman: - CCC = ; -Bias = pixels. | - Sensitivity = ; - Specificity = ; - RDR = . | - Inability to quantify nerve tortuosity/width; - Single-center. |

| [65] | 2021 | Compare GAN vs. U-Net for corneal sub-basal nerve segmentation. | - GAN; - U-Net. | - 510 IVCM images (85 subjects). | - Training 403 images (augmented); - Testing: 102 images. | - ICC (inter-rater): ( CI: –). | - GAN: AUC = ; - U-Net: AUC = . | - Small dataset; - Device-specific; - No external validation. |

| [66] | 2021 | Quantify CSNT & correlate with clinical parameters. | - IPACHI; - KNN. | - 1501 IVCM (49 patients). | - Preprocessing; - Local-phase-based enhancement; - IPACHI segmentation. | - OSDI (r = ); - TBUT ; - High expert agreement. | - F value (). | - Limited sample size; - Not tear composition data; - Not analyzing the whole corneal nerve plexus. |

| [67] | 2022 | CNF + DC segmentation & evaluation. | U-Net + Mask R-CNN | - 1219 IVCM images (China); - 754 IVCM images (Germany). | - Training: 10-fold CV; - DA: flips, rotation, gamma contrast, random crop. | CNFs:- Nerve number: ; - Length: ; - Branching points: ; - Tortuosity: . DCs: - Cell number: ; - Size: . | CNF Model: - Sensitivity = ; - Specificity = ; DC Model: - Precision = ; - Recall = ; F1 score = . | - Small cohorts; - Manual annotation variability is not fully addressed. |

| Study Ref. | Year | Purpose | Learning Model | Data Source | Development Strategy | Correlation with Experts | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [68] | 2023 | Corneal staining evaluation. | SVM | - 421 slit-lamp images. | - Image preprocessing; - ROI detection; - Segmentation; - Feature extraction; - Feature selection; - Models tested: DT, BT, NB, KNN, RF. | - ICC = . | - Accuracy: ; - AUC: . | - Single-center with moderate dataset size; - Large- or low-contrast staining patches. |

| [69] | 2022 | DED severity grading. | ImageJ | - 50 fluorescein images (slit lamp). | - Preprocessing; - Analysis; - Count the number of particles; - OGS grading; - 30 test images. | - Moderate intrarater (K = ). | - Sr = vs. true Oxford grade. | - Limited sample size. |

| [70] | 2024 | Automated DED severity grading. | - U-Net + VGG16. | - 1400 images (1100 DED patients); - 94 External validation. | - 5-fold CV; - Grid-based corneal division; - Trained on 200 labeled images. | - Internal validation: ; - External validation: ; - Inter-rater agreement: ; | - Accuracy = ; - Sensitivity = ; - Specificity = ; - AUC = . | - Some zone occlusion; - No yellow filter; - Risk of FN in low contrast cases. |

| [71] | 2024 | Corneal staining grading. | ResNet50 (FKD-CSS) | - 3847 images (37 hospitals). | - ROI extraction; - Lesion-aware teacher; - Interpretable regression. | - Pearson r = 0.84–0.90 externally, outperforming experts (AUC ); | - AUC = | - Moderate severity grading; - Limited to Chinese (Asian) population. |

| [72] | 2023 | Estimate TFBUT, DED. | Swin Transformer. | - 16,440 frames (158 eyes). | - T raining: 12,011; - Validation: 2830; - Test: 1599 frames; - DA; - Resize and crop. | - Spearman r = with EMR TFBUT. | - Sensitivity: ; - Specificity: ; - AUC: ; - PPV: ; - NPV: . | - Small and imbalanced dataset; - Model based only on the Japanese population. |

| [73] | 2024 | Estimate TBUT. | DTSN (InceptionV3, EfficientNetB3NS). | - 67 videos (France). | - Frame classification + temporal smoothing. | - Pearson vs. ophthalmologist. | - AUC = . | - Single centered; - Limited diversity. |

| [74] | 2020 | SPK Grading. | CNN | - 101 slit lamp images. | - Data collection; - Ophthalmologist grading; Manual selection of the ROI; - Model training; - DA; - CNN-SPK detection. | - CNN-SPK vs. clinical grading (r = , ). | - Sensitivity = ; - Specificity = ; - Accuracy = 97%. | - One eye per patient; - Limited sample size. |

| [75] | 2024 | Detection + monitoring of DED. | U-Net + YOLOv5. | - 2440 slit-lamp; - 1200 meibography. | Dual-mode RGB/IR CNNs + postprocessing. | Model matched expert MG evaluation. | - Accuracy ; - F1 up to . | - Clinical validation needed for long-term deployment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harti, M.E.; Andaloussi, S.J.; Ouchetto, O. A Comprehensive Review Comparing Artificial Intelligence and Clinical Diagnostic Approaches for Dry Eye Disease. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3071. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233071

Harti ME, Andaloussi SJ, Ouchetto O. A Comprehensive Review Comparing Artificial Intelligence and Clinical Diagnostic Approaches for Dry Eye Disease. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3071. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233071

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarti, Manal El, Said Jai Andaloussi, and Ouail Ouchetto. 2025. "A Comprehensive Review Comparing Artificial Intelligence and Clinical Diagnostic Approaches for Dry Eye Disease" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3071. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233071

APA StyleHarti, M. E., Andaloussi, S. J., & Ouchetto, O. (2025). A Comprehensive Review Comparing Artificial Intelligence and Clinical Diagnostic Approaches for Dry Eye Disease. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3071. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233071