Mechanisms and Impact of Cognitive Reserve in Normal Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

Cognitive Reserve

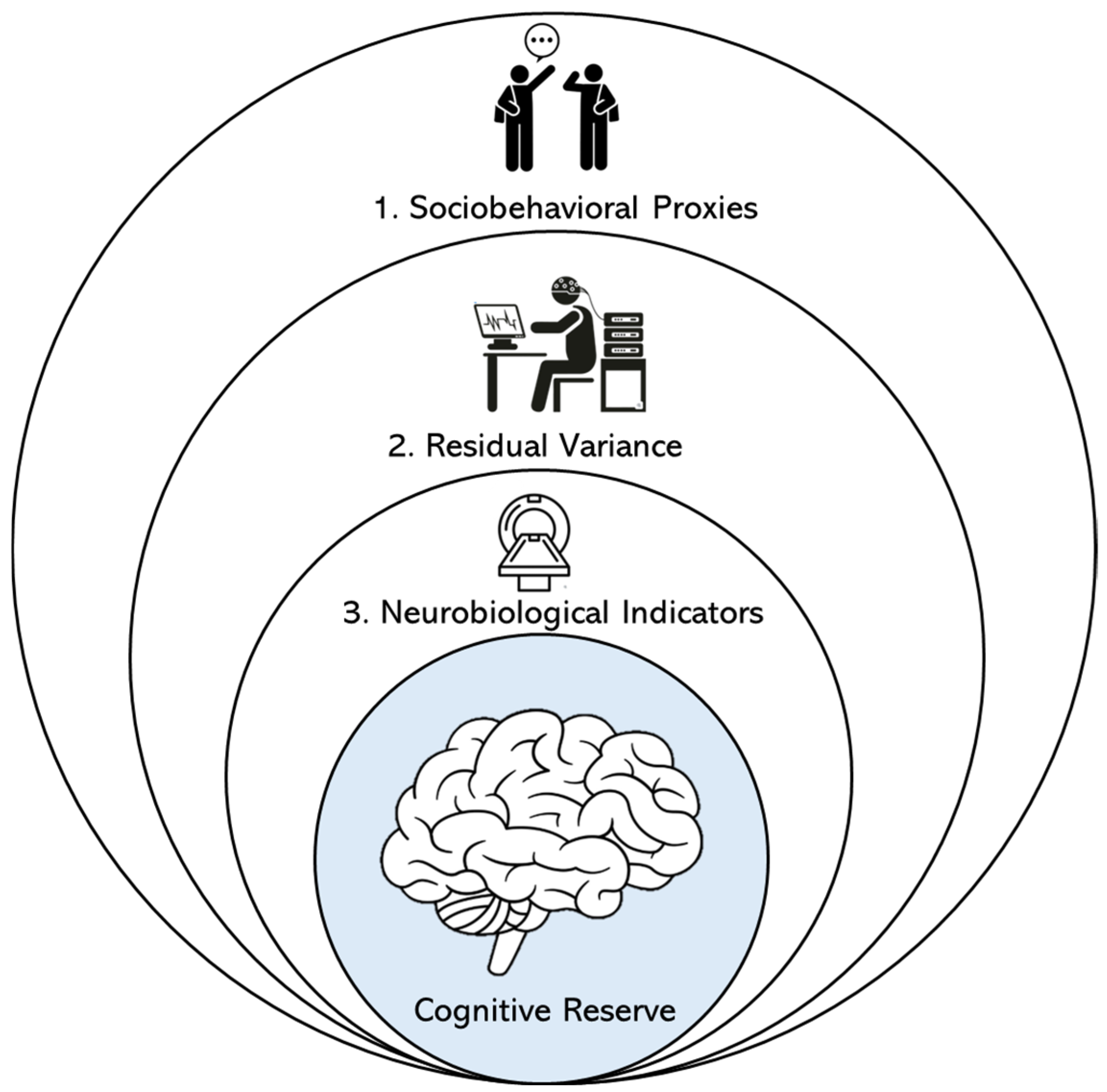

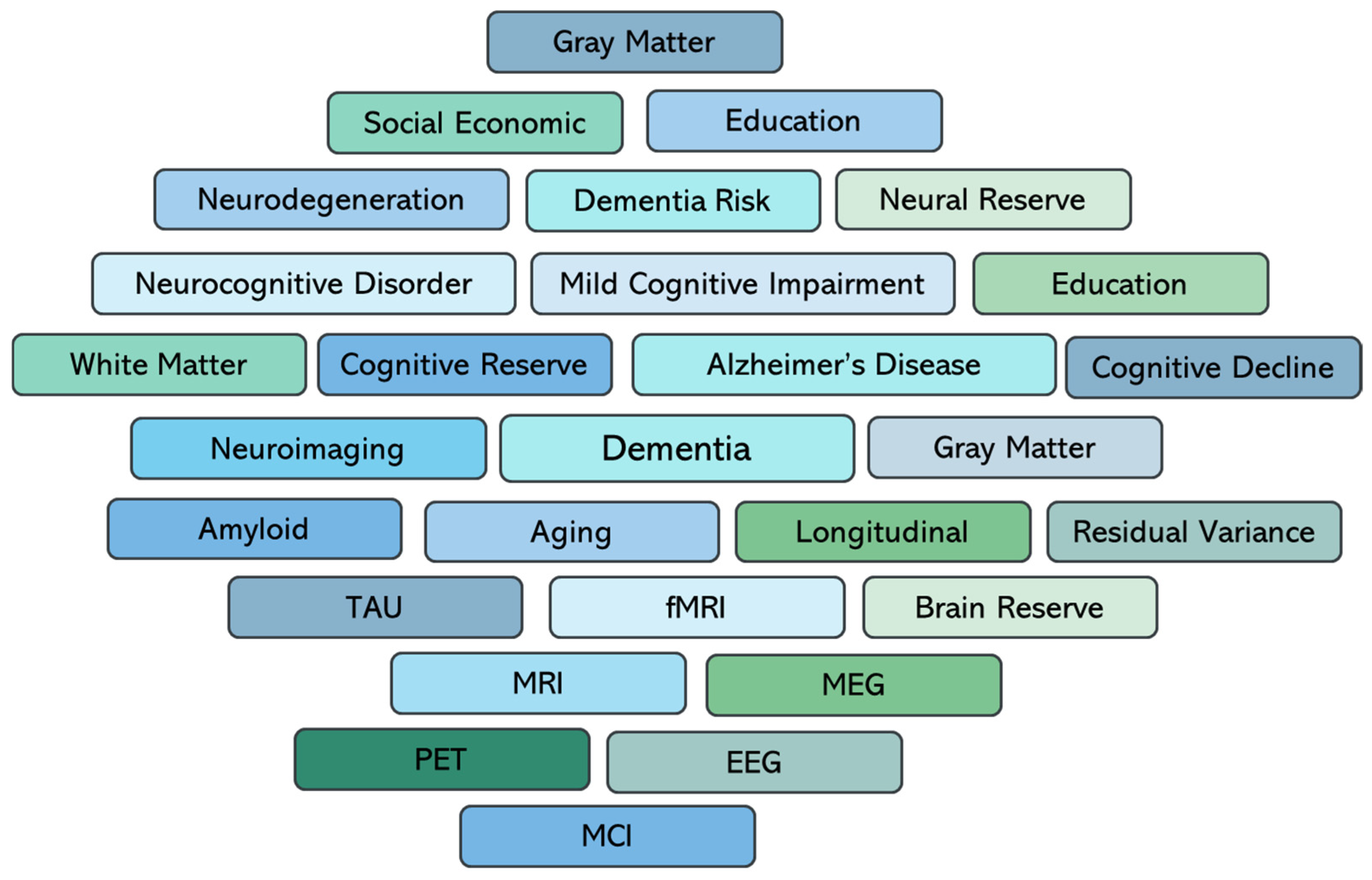

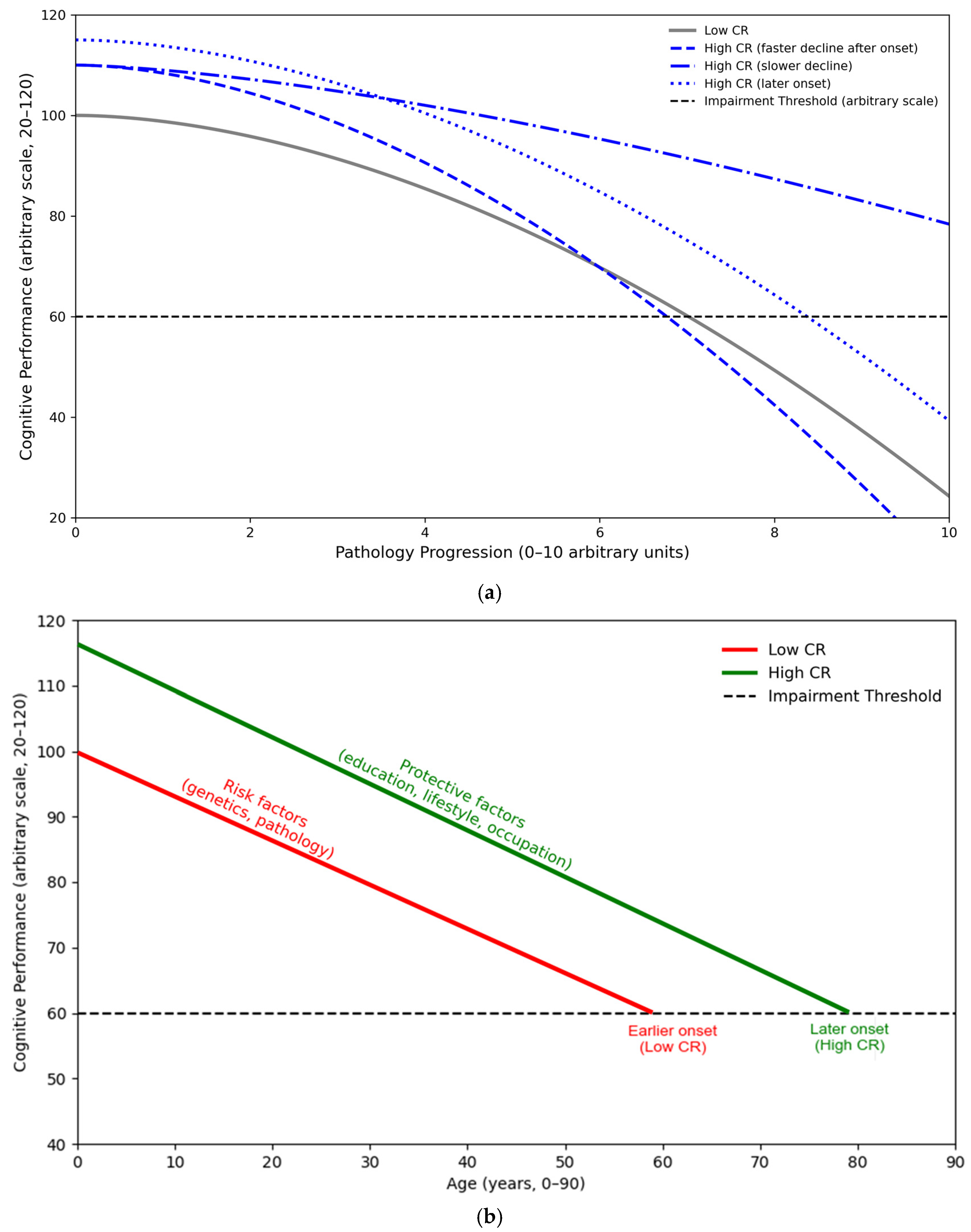

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesized Effects of Cognitive Reserve

3. Purpose of Current Review

4. Literature Search

5. Sociobehavioral Proxy Measures of Cognitive Reserve

Social Cognitive Reserve Proxies and Cognitive Decline in Cohort Studies

6. Residual Variance Approaches to Cognitive Reserve

Longitudinal Evidence for Residual-Based Cognitive Reserve

7. Neurobiological Indicator Approaches to Cognitive Reserve

Longitudinal Studies of Neurobiological Indicators

8. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2019 Dementia Forecasting Collaborators. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzheimer’s Association. 2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; van Boxtel, M.; Breteler, M.; Ceccaldi, M.; Chételat, G.; Dubois, B.; Dufouil, C.; Ellis, K.A.; van der Flier, W.M.; et al. Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative (SCD-I) Working Group. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2014, 10, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinuevo, J.L.; Rabin, L.A.; Amariglio, R.; Buckley, R.; Dubois, B.; Ellis, K.A.; Ewers, M.; Hampel, H.; Klöppel, S.; Rami, L.; et al. Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative (SCD-I) Working Group. Implementation of subjective cognitive decline criteria in research studies. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2017, 13, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongsiriyanyong, S.; Limpawattana, P. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice: A Review Article. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2018, 33, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiri, S.; Ghaffari Jolfayi, A.; Fazlollahi, A.; Morsali, S.; Sarkesh, A.; Daei Sorkhabi, A.; Golabi, B.; Aletaha, R.; Motlagh Asghari, K.; Hamidi, S.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease: A comprehensive review of epidemiology, risk factors, symptoms diagnosis, management, caregiving, advanced treatments and associated challenges. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1474043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Zhou, Q.A. Alzheimer’s Disease: Exploring the Landscape of Cognitive Decline. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 3800–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Márquez, F.; Yassa, M.A. Neuroimaging Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, R.; Li, B.; Bishnoi, R. P-tau217 as a Reliable Blood-Based Marker of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Barve, K.H.; Kumar, M.S. Recent Advancements in Pathogenesis, Diagnostics and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R., Jr.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huszár, Z.; Solomon, A.; Engh, M.A.; Koszovácz, V.; Terebessy, T.; Molnár, Z.; Hegyi, P.; Horváth, A.; Mangialasche, F.; Kivipelto, M.; et al. Association of modifiable risk factors with progression to dementia in relation to amyloid and tau pathology. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornish, D.; Madison, C.; Kivipelto, M.; Kemp, C.; McCulloch, C.E.; Galasko, D.; Artz, J.; Rentz, D.; Lin, J.; Norman, K.; et al. Effects of intensive lifestyle changes on the progression of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Recent advances in Alzheimer’s disease: Mechanisms, clinical trials and new drug development strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Vemuri, P. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: Clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology 2018, 90, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, K.; Carrière, I.; Berr, C.; Amieva, H.; Dartigues, J.F.; Ancelin, M.L.; Ritchie, C.W. The clinical picture of Alzheimer’s disease in the decade before diagnosis: Clinical and biomarker trajectories. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, e305–e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, P.A.; Yu, L.; Wilson, R.S.; Leurgans, S.E.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A. Person-specific contribution of neuropathologies to cognitive loss in old Age. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 83, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, Y.; Arenaza-Urquijo, E.M.; Bartrés-Faz, D.; Belleville, S.; Cantilon, M.; Chetelat, G.; Ewers, M.; Franzmeier, N.; Kempermann, G.; Kremen, W.S.; et al. Whitepaper: Defining and investigating cognitive reserve, brain reserve, and brain maintenance. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2020, 16, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarimuthu, A.; Ponniah, R.J. Cognition and Cognitive Reserve. Integr. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2024, 58, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemuri, P.; Weigand, S.D.; Przybelski, S.A.; Knopman, D.S.; Smith, G.E.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Shaw, L.M.; Decarli, C.S.; Carmichael, O.; Bernstein, M.A.; et al. Cognitive reserve and Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers are independent determinants of cognition. Brain J. Neurol. 2011, 134 Pt 5, 1479–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, C.; Soldan, A. Defining Cognitive Reserve and Implications for Cognitive Aging. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2019, 19, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barulli, D.; Stern, Y. Efficiency, capacity, compensation, maintenance, plasticity: Emerging concepts in cognitive reserve. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapko, D.; McCormack, R.; Black, C.; Staff, R.; Murray, A. Life-course determinants of cognitive reserve (CR) in cognitive aging and dementia—A systematic literature review. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loenhoud, A.C.; van der Flier, W.M.; Wink, A.M.; Dicks, E.; Groot, C.; Twisk, J.; Barkhof, F.; Scheltens, P.; Ossenkoppele, R.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Cognitive reserve and clinical progression in Alzheimer disease: A paradoxical relationship. Neurology 2019, 93, e334–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ren, Y.; Cong, L.; Hou, T.; Song, L.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Han, X.; Tang, S.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Association of Lifelong Cognitive Reserve with Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment among Older Adults with Limited Formal Education: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2023, 52, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappalettera, C.; Carrarini, C.; Miraglia, F.; Vecchio, F.; Rossini, P.M. Cognitive resilience/reserve: Myth or reality? A review of definitions and measurement methods. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2024, 20, 3567–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2006, 20, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, C.; Nazarovs, J.; Soldan, A.; Singh, V.; Wang, J.; Hohman, T.; Dumitrescu, L.; Libby, J.; Kunkle, B.; Gross, A.L.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease genetic risk and cognitive reserve in relationship to long-term cognitive trajectories among cognitively normal individuals. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2023, 15, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, R.; Albert, M.; Belleville, S.; Craik, F.I.M.; Duarte, A.; Grady, C.L.; Lindenberger, U.; Nyberg, L.; Park, D.C.; Reuter-Lorenz, P.A.; et al. Maintenance, reserve and compensation: The cognitive neuroscience of healthy ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Stern, Y.; Gu, Y. Modifiable lifestyle factors and cognitive reserve: A systematic review of current evidence. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 74, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valenzuela, M.J.; Sachdev, P. Brain reserve and cognitive decline: A non-parametric systematic review. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichele, S.R. Cognitive reserve as residual variance in cognitive performance: Latent dimensionality, correlates, and dementia prediction. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2024, 30, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, F.; Kalpouzos, G.; Laukka, E.J.; Wang, R.; Qiu, C.; Bäckman, L.; Marseglia, A.; Fratiglioni, L.; Dekhtyar, S. Cognitive Trajectories and Dementia Risk: A Comparison of Two Cognitive Reserve Measures. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 737736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazes, Y.; Lee, S.; Fang, Z.; Mensing, A.; Noofoory, D.; Hidalgo Nazario, G.; Babukutty, R.; Chen, B.B.; Habeck, C.; Stern, Y. Effects of Brain Maintenance and Cognitive Reserve on Age-Related Decline in Three Cognitive Abilities. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2023, 78, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, F.; Negri, I. How Cognitive Reserve Could Protect from Dementia? An Analysis of Everyday Activities and Social Behaviors During Lifespan. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vemuri, P.; Lesnick, T.G.; Przybelski, S.A.; Machulda, M.; Knopman, D.S.; Mielke, M.M.; Roberts, R.O.; Geda, Y.E.; Rocca, W.A.; Petersen, R.C.; et al. Association of lifetime intellectual enrichment with cognitive decline in the older population. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.F.; Tan, M.S.; Tan, L.; Li, J.Q.; Zhao, Q.F.; Yu, J.T. Education and Risk of Dementia: Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 3113–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldan, A.; Pettigrew, C.; Cai, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.C.; Moghekar, A.; Miller, M.I.; Albert, M.; BIOCARD Research Team. Cognitive reserve and long-term change in cognition in aging and preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2017, 60, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzmeier, N.; Duering, M.; Weiner, M.; Dichgans, M.; Ewers, M.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Left frontal cortex connectivity underlies cognitive reserve in prodromal Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2017, 88, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJong, N.R.; Jansen, J.F.A.; van Boxtel, M.P.J.; Schram, M.T.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Dagnelie, P.C.; van der Kallen, C.J.H.; Kroon, A.A.; Wesselius, A.; Koster, A.; et al. Cognitive resilience depends on white matter connectivity: The Maastricht Study. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2023, 19, 1164–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Tan, L.; Wang, H.F.; Jiang, T.; Tan, M.S.; Tan, L.; Zhao, Q.F.; Li, J.Q.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.T. Meta-analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 86, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; D’Arcy, C. Education and dementia in the context of the cognitive reserve hypothesis: A systematic review with meta-analyses and qualitative analyses. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foverskov, E.; Glymour, M.M.; Mortensen, E.L.; Holm, A.; Lange, T.; Lund, R. Education and Cognitive Aging: Accounting for Selection and Confounding in Linkage of Data From the Danish Registry and Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 2423–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, J.; Kantipudi, S.J.; Vinoth, S.; Kuchipudi, J.D. Prevalence of subjective cognitive decline and its association with physical health problems among urban community dwelling elderly population in South India. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2025, 21, e14505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, A.; Karim, H.T.; Ly, M.J.; Cohen, A.D.; Lopresti, B.J.; Mathis, C.A.; Klunk, W.E.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Snitz, B.E. An Effect of Education on Memory-Encoding Activation in Subjective Cognitive Decline. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 81, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manly, J.J.; Schupf, N.; Tang, M.X.; Stern, Y. Cognitive decline and literacy among ethnically diverse elders. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2005, 18, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavé, G.; Shrira, A.; Palgi, Y.; Spalter, T.; Ben-Ezra, M.; Shmotkin, D. Formal education level versus self-rated literacy as predictors of cognitive aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2012, 67, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, C.; Garcia, A.; Clay, O.J.; Wadley, V.G.; Andel, R.; Dávila, A.L.; Crowe, M. Quality of Education and Late-Life Cognitive Function in a Population-Based Sample From Puerto Rico. Innov. Aging 2021, 5, igab016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, L.J.; Abshire Saylor, M.; Choe, M.Y.; Smith Wright, R.; Kim, B.; Nkimbeng, M.; Mena-Carrasco, F.; Beak, J.; Szanton, S.L. Financial strain measures and associations with adult health: A systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 364, 117531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andel, R.; Crowe, M.; Kåreholt, I.; Wastesson, J.; Parker, M.G. Indicators of job strain at midlife and cognitive functioning in advanced old Age. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2011, 66, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, K.Y.; Xu, W.; Mangialasche, F.; Dekhtyar, S.; Fratiglioni, L.; Wang, H.X. Working Life Psychosocial Conditions in Relation to Late-Life Cognitive Decline: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 67, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, E.L.; Gow, A.J.; Deary, I.J. Occupational complexity and lifetime cognitive abilities. Neurology 2014, 83, 2285–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkel, D.; Andel, R.; Gatz, M.; Pedersen, N.L. The role of occupational complexity in trajectories of cognitive aging before and after retirement. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verghese, J.; Lipton, R.B.; Katz, M.J.; Hall, C.B.; Derby, C.A.; Kuslansky, G.; Ambrose, A.F.; Sliwinski, M.; Buschke, H. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2508–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratiglioni, L.; Paillard-Borg, S.; Winblad, B. An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, B.D.; Wilson, R.S.; Barnes, L.L.; Bennett, D.A. Late-life social activity and cognitive decline in old age. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2011, 17, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.; O’Sullivan, R.; Caserotti, P.; Tully, M.A. Consequences of physical inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Tao, S.; Yin, H.C.; Shen, Q.Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L.N.; Li, X.J. Tai Chi Chuan Alters Brain Functional Network Plasticity and Promotes Cognitive Flexibility. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 665419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marioni, R.E.; Proust-Lima, C.; Amieva, H.; Brayne, C.; Matthews, F.E.; Dartigues, J.F.; Jacqmin-Gadda, H. Social activity, cognitive decline and dementia risk: A 20-year prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.; Deary, I.J. A life course approach to cognitive reserve: A model for cognitive aging and development? Ann. Neurol. 2005, 58, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalley, L.J.; Deary, I.J.; Appleton, C.L.; Starr, J.M. Cognitive reserve and the neurobiology of cognitive aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2004, 3, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalley, L.J.; Starr, J.M.; Athawes, R.; Hunter, D.; Pattie, A.; Deary, I.J. Childhood mental ability and dementia. Neurology 2000, 55, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Time Spent on Social Network Sites and Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K.P.; Snowdon, D.A.; Desrosiers, M.F.; Markesbery, W.R. Early life linguistic ability, late life cognitive function, and neuropathology: Findings from the Nun Study. Neurobiol. Aging 2005, 26, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, M.C.; Smith, K.R.; Østbye, T.; Tschanz, J.T.; Schwartz, S.; Corcoran, C.; Breitner, J.C.; Steffens, D.C.; Skoog, I.; Rabins, P.V.; et al. Early parental death and remarriage of widowed parents as risk factors for Alzheimer disease: The Cache County study. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 19, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechtel, P.; Pizzagalli, D.A. Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: An integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology 2011, 214, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, M.; Jones, S.; Maden, M.; Du, B.; Mc, R.; Kumaran, K.; Karat, S.C.; Fall, C.H.D. Size at birth and cognitive ability in late life: A systematic review. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 1139–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E.; Craik, F.I.; Freedman, M. Bilingualism as a protection against the onset of symptoms of dementia. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, E. Bilingualism: Pathway to Cognitive Reserve. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdebeeck, C.; Martyr, A.; Clare, L. Cognitive reserve and cognitive function in healthy older people: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cognition. Sect. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 2016, 23, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Meza, P.; Steptoe, A.; Cadar, D. Markers of cognitive reserve and dementia incidence in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Br. J. Psychiatry J. Ment. Sci. 2021, 218, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldan, A.; Pettigrew, C.; Albert, M. Evaluating Cognitive Reserve Through the Prism of Preclinical Alzheimer Disease. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 41, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Chen, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Luo, W.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, B.; Xu, R.; Xi, C. Higher Cognitive Reserve Is Beneficial for Cognitive Performance Via Various Locus Coeruleus Functional Pathways in the Pre-Dementia Stage of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 11, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Boyle, P.A.; Yu, L.; Barnes, L.L.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A. Life-span cognitive activity, neuropathologic burden, and cognitive aging. Neurology 2013, 81, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, D.A.; Wilson, R.S.; Schneider, J.A.; Evans, D.A.; Mendes de Leon, C.F.; Arnold, S.E.; Barnes, L.L.; Bienias, J.L. Education modifies the relation of AD pathology to level of cognitive function in older persons. Neurology 2003, 60, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahodne, L.B.; Stern, Y.; Manly, J.J. Differing effects of education on cognitive decline in diverse elders with low versus high educational attainment. Neuropsychology 2015, 29, 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B.R.; Mungas, D.; Farias, S.T.; Harvey, D.; Beckett, L.; Widaman, K.; Hinton, L.; DeCarli, C. Measuring cognitive reserve based on the decomposition of episodic memory variance. Brain A J. Neurol. 2010, 133 Pt 8, 2196–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.B.; Derby, C.; LeValley, A.; Katz, M.J.; Verghese, J.; Lipton, R.B. Education delays accelerated decline on a memory test in persons who develop dementia. Neurology 2007, 69, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Li, Y.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Barnes, L.L.; McCann, J.J.; Gilley, D.W.; Evans, D.A. Education and the course of cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2004, 63, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Song, R.; Qi, X.; Xu, H.; Yang, W.; Kivipelto, M.; Bennett, D.A.; Xu, W. Influence of Cognitive Reserve on Cognitive Trajectories: Role of Brain Pathologies. Neurology 2021, 97, e1695–e1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.M.; Laidlaw, D.H.; Cabeen, R.; Akbudak, E.; Conturo, T.E.; Correia, S.; Tate, D.F.; Heaps-Woodruff, J.M.; Brier, M.R.; Bolzenius, J.; et al. Cognitive reserve moderates the relationship between neuropsychological performance and white matter fiber bundle length in healthy older adults. Brain Imaging Behav. 2017, 11, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.N.; Manly, J.; Glymour, M.M.; Rentz, D.M.; Jefferson, A.L.; Stern, Y. Conceptual and measurement challenges in research on cognitive reserve. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2011, 17, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, S.P.; Lampraki, C.; Dos Santos Rêgo, T.; Ghisletta, P.; Kliegel, M.; Maurer, J.; Studer, M.; Gouveia, É.R.; de Maio Nascimento, M.; Ihle, A. Can cognitive reserve offset APOE-related Alzheimer’s risk? A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 110, 102809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saywell, I.; Foreman, L.; Child, B.; Phillips-Hughes, A.L.; Collins-Praino, L.; Baetu, I. Influence of cognitive reserve on cognitive and motor function in α-synucleinopathies: A systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 161, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewers, M.; Insel, P.S.; Stern, Y.; Weiner, M.W.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Cognitive reserve associated with FDG-PET in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2013, 80, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marselli, G.; Favieri, F.; Forte, G.; Corbo, I.; Agostini, F.; Guarino, A.; Casagrande, M. The protective role of cognitive reserve: An empirical study in mild cognitive impairment. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahodne, L.B.; Manly, J.J.; Brickman, A.M.; Narkhede, A.; Griffith, E.Y.; Guzman, V.A.; Schupf, N.; Stern, Y. Is residual memory variance a valid method for quantifying cognitive reserve? A longitudinal application. Neuropsychologia 2015, 77, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahodne, L.B.; Glymour, M.M.; Sparks, C.; Bontempo, D.; Dixon, R.A.; MacDonald, S.W.; Manly, J.J. Education does not slow cognitive decline with aging: 12-year evidence from the victoria longitudinal study. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2011, 17, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, Z.A.; Sheridan, A.M.C.; Silk, T.J.; Anderson, V.; Weinborn, M.; Gavett, B.E. Modeling the development of cognitive reserve in children: A residual index approach. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2024, 30, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraal, A.Z.; Massimo, L.; Fletcher, E.; Carrión, C.I.; Medina, L.D.; Mungas, D.; Gavett, B.E.; Farias, S.T. Functional reserve: The residual variance in instrumental activities of daily living not explained by brain structure, cognition, and demographics. Neuropsychology 2021, 35, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, F.; Grothe, M.J.; Dyrba, M.; Franzmeier, N.; Teipel, S.J.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Longitudinal trajectories of cognitive reserve in hypometabolic subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2024, 135, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elman, J.A.; Vogel, J.W.; Bocancea, D.I.; Ossenkoppele, R.; van Loenhoud, A.C.; Tu, X.M.; Kremen, W.S.; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Issues and recommendations for the residual approach to quantifying cognitive resilience and reserve. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Seo, S.W.; Roh, J.H.; Oh, M.; Oh, J.S.; Oh, S.J.; Kim, J.S.; Jeong, Y. Effects of Cognitive Reserve in Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitively Unimpaired Individuals. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 13, 784054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.P.; Schultz, S.A.; Austin, B.P.; Boots, E.A.; Dowling, N.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Bendlin, B.B.; Sager, M.A.; Hermann, B.P.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Effect of Cognitive Reserve on Age-Related Changes in Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers of Alzheimer Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, C.; Soldan, A.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Wang, M.C.; Moghekar, A.; Miller, M.I.; Singh, B.; Martinez, O.; Fletcher, E.; et al. Cognitive reserve and rate of change in Alzheimer’s and cerebrovascular disease biomarkers among cognitively normal individuals. Neurobiol. Aging 2020, 88, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hu, J.; Gui, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, J. Longitudinal validation of cognitive reserve proxy measures: A cohort study in a rural Chinese community. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, N.; Rezapour, T.; Kormi-Nouri, R.; Abdekhodaie, E.; Ghamsari, A.M.; Ehsan, H.B.; Hatami, J. The effects of different proxies of cognitive reserve on episodic memory performance: Aging study in Iran. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, L.; Wu, Y.T.; Teale, J.C.; MacLeod, C.; Matthews, F.; Brayne, C.; Woods, B.; CFAS-Wales Study Team. Potentially modifiable lifestyle factors, cognitive reserve, and cognitive function in later life: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2017, 14, e1002259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiler, M.; Casseb, R.F.; de Campos, B.M.; de Ligo Teixeira, C.V.; Carletti-Cassani, A.F.M.K.; Vicentini, J.E.; Magalhães, T.N.C.; de Almeira, D.Q.; Talib, L.L.; Forlenza, O.V.; et al. Cognitive Reserve Relates to Functional Network Efficiency in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Um, Y.H.; Wang, S.M.; Kim, R.E.; Choe, Y.S.; Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Lim, H.K.; Lee, C.U.; et al. Associations between Education Years and Resting-state Functional Connectivity Modulated by APOE ε4 Carrier Status in Cognitively Normal Older Adults. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. Off. Sci. J. Korean Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024, 22, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Burgos, L.; Barroso, J.; Ferreira, D. Cognitive reserve and network efficiency as compensatory mechanisms of the effect of aging on phonemic fluency. Aging 2020, 12, 23351–23378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerramalla, M.S.; Darin-Mattsson, A.; Udeh-Momoh, C.T.; Holleman, J.; Kåreholt, I.; Aspö, M.; Hagman, G.; Kivipelto, M.; Solomon, A.; Marseglia, A.; et al. Cognitive reserve, cortisol, and Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers: A memory clinic study. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2024, 20, 4486–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, H.; Fung, H.H. The moderating effect of cognitive reserve on the association between neuroimaging biomarkers and cognition: A systematic review. Neurobiol. Aging 2025, 156, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuki, A.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Kozakai, R.; Ando, F.; Shimokata, H. Relationship between physical activity and brain atrophy progression. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Neumann, A.; Hofman, A.; Vernooij, M.W.; Neitzel, J. The bidirectional relationship between brain structure and physical activity: A longitudinal analysis in the UK Biobank. Neurobiol. Aging 2024, 138, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, R.J.; Jonaitis, E.M.; Gaitán, J.M.; Lose, S.R.; Mergen, B.M.; Johnson, S.C.; Okonkwo, O.C.; Cook, D.B. Cardiorespiratory fitness mitigates brain atrophy and cognitive decline in adults at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 13, e12212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Wanigatunga, A.A.; An, Y.; Liu, F.; Spira, A.P.; Davatzikos, C.; Tian, Q.; Simonsick, E.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Resnick, S.M.; et al. Longitudinal associations between energy utilization and brain volumes in cognitively normal middle aged and older adults. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedsalehi, A.; Warrier, V.; Bethlehem, R.A.I.; Perry, B.I.; Burgess, S.; Murray, G.K. Educational attainment, structural brain reserve and Alzheimer’s disease: A Mendelian randomization analysis. Brain J. Neurol. 2023, 146, 2059–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Design/Sample | CR Proxy | Covariates/Confounders Controlled | Key Findings | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stern 2012 [15] | Narrative + empirical models; multiple cohorts | Education, IQ, occupation | Varied across cohorts; SES often partial; APOE rarely included | CR moderates clinical expression of AD pathology | Heterogeneous measures; limited biomarker integration |

| Vemuri et al., 2011 (ADNI) [21] | Longitudinal; n ≈ 300 CN/MCI/AD | Education, occupation | Age, sex, MRI, FDG-PET; no SES, no APOE | CR and biomarkers independently predict cognition | CR proxies limited; SES/education quality unmeasured |

| Soldan et al., 2017 (BIOCARD) [39] | 20-year longitudinal; n ≈ 350 CN | Residual variance (memory) | Age, sex, MRI, CSF Aβ/tau; APOE included | Higher residual-CR predicts slower decline | Highly educated cohort; limited SES diversity |

| Franzmeier et al., 2017 [40] | fMRI connectivity; n ≈ 100 MCI | Education, connectivity | Age, sex, hippocampal volume; APOE included | Left frontal connectivity underlies CR | Small sample; connectivity measures variable |

| Gazes et al., 2023 [35] | 5-year longitudinal; n = 254 | IQ, education | Age, sex, cortical thickness, MD; no SES | CR and brain maintenance independently predict decline | Mid-SES sample; cognitive tests limited |

| DeJong et al., 2023 [41] | Population dMRI cohort; n = 4759 | Structural connectivity | SES, vascular risks; no APOE | Connectivity buffers effect of atrophy on cognition | Cross-sectional cognition; dMRI quality variable |

| van Loenhoud et al., 2019 [25] | ADNI; n ≈ 500 | Education | Age, sex, Aβ, tau; APOE included | Paradoxical faster decline in high-CR once symptomatic | CR paradox sensitive to model assumptions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simfukwe, C.; An, S.S.A.; Youn, Y.C. Mechanisms and Impact of Cognitive Reserve in Normal Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233068

Simfukwe C, An SSA, Youn YC. Mechanisms and Impact of Cognitive Reserve in Normal Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233068

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimfukwe, Chanda, Seong Soo A. An, and Young Chul Youn. 2025. "Mechanisms and Impact of Cognitive Reserve in Normal Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233068

APA StyleSimfukwe, C., An, S. S. A., & Youn, Y. C. (2025). Mechanisms and Impact of Cognitive Reserve in Normal Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3068. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233068