Different Patterns of Cortical Electrical Activity by Tactile, Acoustic and Visual Stimuli in Infants: An EEG Exploratory Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Sample

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Variable

2.4. Material

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| HZ | Hertz |

| HD-DOT | High-density optical tomography |

| PSD | Power spectrum density |

References

- Rener-Primec, Z.; Neubauer, D.; Osredkar, D. Dysmature patterns of newborn EEG recordings: Biological markers of transitory brain dysfunction or brain injury. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2022, 38, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, J.S.; Tharp, B.R. The dysmature EEG pattern in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and its prognostic implications. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1990, 76, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Hayakawa, F.; Okumura, A. Neonatal EEG: A powerful tool in the assessment of brain damage in preterm infants. Brain Dev. 1999, 21, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellhaas, R.A.; Wusthoff, C.J.; Tsuchida, T.N.; Glass, H.C.; Chu, C.J.; Massey, S.L.; Soul, J.S.; Wiwattanadittakun, N.; Abend, N.S.; Cilio, M.R. Profile of neonatal epilepsies: Characteristics of a prospective US cohort. Neurology 2017, 89, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, N.J.; Tapani, K.; Lauronen, L.; Vanhatalo, S. A dataset of neonatal EEG recordings with seizure annotations. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 190039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamblin, M.D.; André, M.; Challamel, M.J.; Curzi-Dascalova, L.; d’Allest, A.M.; De Giovanni, E.; Moussalli-Salefranque, F.; Navelet, Y.; Plouin, P.; Radvanyi-Bouvet, M.F.; et al. Electroencéphalographie du nouveau-né prématuré et à terme. Aspects maturatifs et glossaire [Electroencephalography of the premature and term newborn. Maturational aspects and glossary]. Neurophysiol. Clin. 1999, 29, 123–219. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toet, M.C.; Hellstrom-Westas, L.; Groenendaal, F.; Eken, P.; de Vries, L.S. Amplitude integrated EEG 3 and 6 hours after birth in full term neonates with hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1999, 81, F19–F23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Wyatt, J.S.; Azzopardi, D.; Ballard, R.; Edwards, A.D.; Ferriero, D.M.; Pollin, R.A.; Robertson, C.M.; Thoresen, M.; Whitelaw, A.; et al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: Multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2005, 365, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kota, S.; Kang, S.; Liu, Y.L.; Liu, H.; Montazeri, S.; Vanhatalo, S.; Chalak, L.F. Prognostic value of quantitative EEG in early hours of life for neonatal encephalopathy and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 96, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, W.S.; Foti, D.; Keehn, B.; Kelleher, B. Resting-state EEG power differences in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, İ.; Garner, R.; Lai, M.; Duncan, D. Unsupervised seizure identification on EEG. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 215, 106604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.K.; Mathur, A. Amplitude-integrated EEG and the newborn infant. Curr. Pediatr. Rev. 2014, 10, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biallas, M.; Trajkovic, I.; Hagmann, C.; Scholkmann, F.; Jenny, C.; Holper, L.; Beck, A.; Wolf, M. Multimodal recording of brain activity in term newborns during photic stimulation by near-infrared spectroscopy and electroencephalography. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17, 086011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, L.; Gervain, J. Speech perception at birth: The brain encodes fast and slow temporal information. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaramella, P.; Freato, F.; Amigoni, A.; Salvadori, S.; Marangoni, P.; Suppiej, A.; Schiavo, B.; Chiandetti, L. Brain auditory activation measured by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in neonates. Pediatr. Res. 2001, 49, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leikos, S.; Tokariev, A.; Koolen, N.; Nevalainen, P.; Vanhatalo, S. Cortical responses to tactile stimuli in preterm infants. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 51, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, C.; Slater, R. Neurophysiological measures of nociceptive brain activity in the newborn infant—The next steps. Acta Paediatr. 2014, 103, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, F.Y.; Fatemi, A.; Johnston, M.V. Cerebral plasticity: Windows of opportunity in the developing brain. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2017, 21, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Weiss, S.M.; Meltzoff, A.N.; Allison, O.N.; Marshall, P.J. Exploring developmental changes in infant anticipation and perceptual processing: EEG responses to tactile stimulation. Infancy 2022, 27, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Kanakogi, Y.; Kawasaki, M.; Myowa, M. The integration of audio-tactile information is modulated by multimodal social interaction with physical contact in infancy. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018, 30, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orioli, G.; Parisi, I.; van Velzen, J.L.; Bremner, A.J. Visual objects approaching the body modulate subsequent somatosensory processing at 4 months of age. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasper, H.H. The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1958, 10, 370–375. [Google Scholar]

- Speckmann, E.J.; Elgar, C.E. Introduction to the Neurophysiological Basis of the EEG and DC Potentials. In Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields; Niedermeyer, E., da Silva, F.L., Eds.; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1999; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Llamas-Ramos, R.; Sánchez-González, J.L.; Alvarado-Omenat, J.J.; Rodríguez-Pérez, V.; Llamas-Ramos, I. Brain electrical activity and oxygenation by Reflex Locomotion Therapy and massage in preterm and term infants. A protocol study. Neuroimage 2024, 298, 120765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An open-source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabard-Durnam, L.J.; Mendez Leal, A.S.; Wilkinson, C.L.; Levin, A.R. The Harvard Automated Processing Pipeline for Electroencephalography (HAPPE): Standardized Processing Software for Developmental and High-Artifact Data. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins-Jones, L.H.; Gossé, L.K.; Blanco, B.; Bulgarelli, C.; Siddiqui, M.; Vidal-Rosas, E.E.; Duobaitė, N.; Nixon-Hill, R.W.; Smith, G.; Skipper, J.; et al. Whole-head high-density diffuse optical tomography to map infant audio-visual responses to social and non-social stimuli. Imaging Neurosci. 2024, 2, imag-2-00244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edalati, M.; Mahmoudzadeh, M.; Ghostine, G.; Kongolo, G.; Safaie, J.; Wallois, F.; Moghimi, S. Preterm neonates distinguish rhythm violation through a hierarchy of cortical processing. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2022, 58, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, M.F.; Marchman, V.A.; Brignoni-Pérez, E.; Dubner, S.; Feldman, H.M.; Scala, M.; Travis, K.E. Inpatient Skin-to-skin Care Predicts 12-Month Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Very Preterm Infants. J. Pediatr. 2024, 274, 114190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, J.S.; Jones, N.A.; Mize, K.D.; Platt, M. Parent-Training with Kangaroo Care Impacts Infant Neurophysiological Development & Mother-Infant Neuroendocrine Activity. Infant. Behav. Dev. 2020, 58, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, A.; Pusil, S.; Acero-Pousa, I.; Zegarra-Valdivia, J.A.; Paltrinieri, A.L.; Bazán, À.; Piras, P.; Palomares, I.; Perera, C.; Garcia-Algar, O.; et al. How can cry acoustics associate newborns’ distress levels with neurophysiological and behavioral signals? Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1266873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. Acoustic enhancement of slow wave sleep-timing and tone: “The details create the big picture”. Sleep 2022, 45, zsac191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.A.J.; Malhotra, A. Electrographic monitoring for seizure detection in the neonatal unit: Current status and future direction. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 96, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van ‘t Westende, C.; Geraedts, V.J.; van Ramesdonk, T.; Dudink, J.; Schoonmade, L.J.; van der Knaap, M.S.; Stam, C.J.; van de Pol, L.A. Neonatal quantitative electroencephalography and long-term outcomes: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2022, 64, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchierini, M.F.; André, M.; d’Allest, A.M. Normal EEG of premature infants born between 24 and 30 weeks gestational age: Terminology, definitions and maturation aspects. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2007, 37, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arichi, T.; Whitehead, K.; Barone, G.; Pressler, R.; Padormo, F.; Edwards, A.D.; Fabrizi, L. Localization of spontaneous bursting neuronal activity in the preterm human brain with simultaneous EEG-fMRI. eLife 2017, 6, e27814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyka, D.; Johnson, M.H.; Lloyd-Fox, S. Infant social interactions and brain development: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 130, 448–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusack, R.; Ball, G.; Smyser, C.D.; Dehaene-Lambertz, G. A neural window on the emergence of cognition. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1369, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

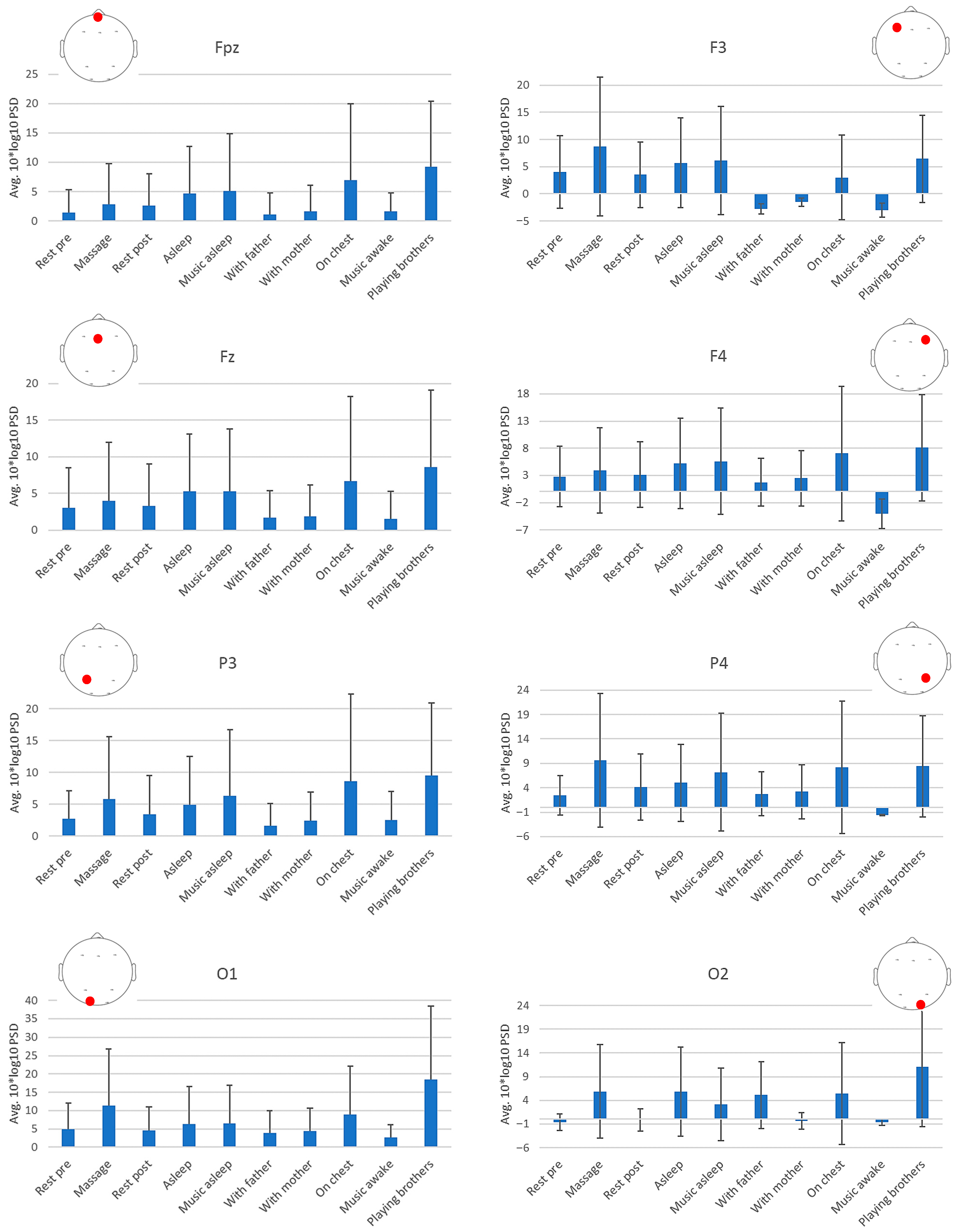

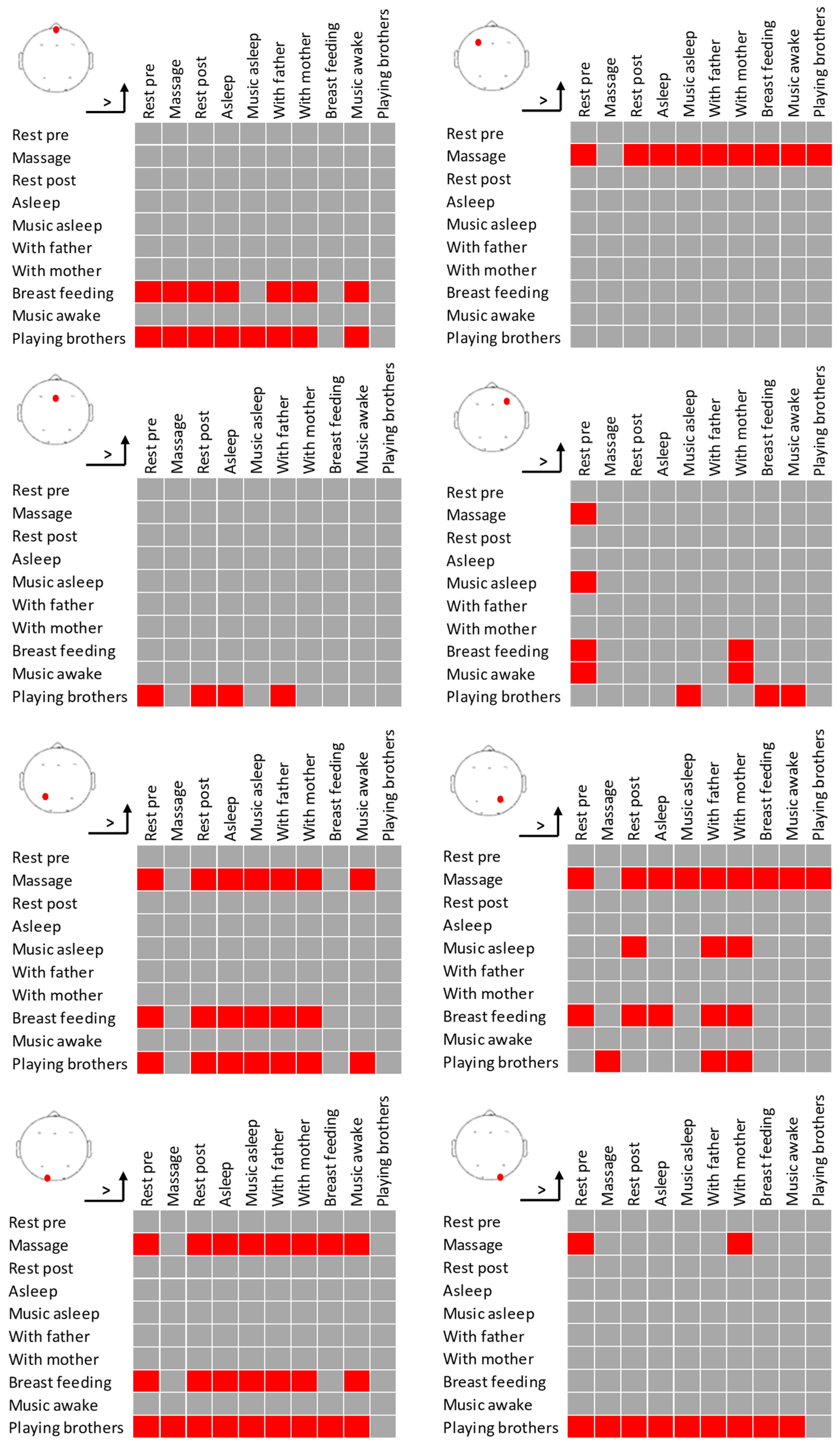

| Avg. 10*log10 PSD (std) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fpz | F3 | Fz | F4 | P3 | P4 | O1 | O2 | |

| Rest pre | 1.367 a (3.904) | 4.028 a (6.650) | 3.061 a (5.397) | 2.782 e,f (5.580) | 2.749 a (4.399) | 2.475 a,c,e (4.033) | 4.982a (7.065) | −0.576a,c (1.722) |

| Massage | 2.855 a (6.867) | 8.750 b (12.784) | 4.006 a,b (7.989) | 3.934 b,c,d,g,h (7.882) | 5.811 c,d (9.765) | 9.641 d (13.648) | 11.430 d (15.381) | 5.909 d (9.922) |

| Rest post | 2.598 a (5.440) | 3.544 a (6.021) | 3.255 a (5.755) | 3.143 a,e,g (6.014) | 3.427 a (6.121) | 4.129 c,e (6.731) | 4.654 a (6.432) | −0.120 a,d,e (2.344) |

| Asleep | 4.701 a (8.001) | 5.731 a (8.213) | 5.269 a (7.841) | 5.247 a,e,g (8.311) | 4.898 a (7.612) | 5.004 a,c,e (7.916) | 6.365 a (10.145) | 5.834 a,d,e (9.370) |

| Music asleep | 5.101 a,b (9.827) | 6.180 a (9.971) | 5.304 a,b (8.530) | 5.617 a,b,h (9.812) | 6.298 a (10.462) | 7.205 a,b (12.061) | 6.588 a (10.351) | 3.188 a,d,e (7.645) |

| With father | 1.130 a (3.662) | −2.807 a (−0.941) | 1.721 a (3.672) | 1.748 a,e,g (4.411) | 1.644 a (3.534) | 2.767 e (4.523) | 3.892 a (6.035) | 5.167 a,d,e (7.070) |

| With mother | 1.664 a (4.368) | −1.493 a (0.766) | 1.876 a,b (4.240) | 2.481 e,h (5.116) | 2.461 a (4.439) | 3.208 e,f (5.516) | 4.354 a (6.291) | −0.322 c,e (1.766) |

| Breastfeeding | 6.914 b,c (13.062) | 3.007 a (7.783) | 6.687 a,b (11.502) | 7.041 a,d (12.371) | 8.603 b,c (13.709) | 8.183 b (13.602) | 9.013 b (13.202) | 5.458 a,d,e (10.748) |

| Music awake | 1.613 a (3.221) | −2.989 a (−1.293) | 1.589 a,b (3.709) | −4.063 a,c (−2.675) | 2.589 a,b (4.415) | −1.595 a,b,c,e (−0.128) | 2.725 a (3.377) | −0.610 a,d,e (0.663) |

| Playing with brothers | 9.229 c (11.217) | 6.468 a (8.024) | 8.576 b (10.494) | 8.083 e,g (9.738) | 9.561 c (11.402) | 8.421 a,b,c (10.379) | 18.460 c (20.052) | 11.099 b (12.666) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llamas-Ramos, R.; Alvarado-Omenat, J.J.; Sánchez-González, J.L.; Sanz-Esteban, I.; Serrano, J.I.; Llamas-Ramos, I. Different Patterns of Cortical Electrical Activity by Tactile, Acoustic and Visual Stimuli in Infants: An EEG Exploratory Study. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233067

Llamas-Ramos R, Alvarado-Omenat JJ, Sánchez-González JL, Sanz-Esteban I, Serrano JI, Llamas-Ramos I. Different Patterns of Cortical Electrical Activity by Tactile, Acoustic and Visual Stimuli in Infants: An EEG Exploratory Study. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233067

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlamas-Ramos, Rocío, Jorge Juan Alvarado-Omenat, Juan Luis Sánchez-González, Ismael Sanz-Esteban, J. Ignacio Serrano, and Inés Llamas-Ramos. 2025. "Different Patterns of Cortical Electrical Activity by Tactile, Acoustic and Visual Stimuli in Infants: An EEG Exploratory Study" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233067

APA StyleLlamas-Ramos, R., Alvarado-Omenat, J. J., Sánchez-González, J. L., Sanz-Esteban, I., Serrano, J. I., & Llamas-Ramos, I. (2025). Different Patterns of Cortical Electrical Activity by Tactile, Acoustic and Visual Stimuli in Infants: An EEG Exploratory Study. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233067