Toward Personalized Response Monitoring in Melanoma Patients Treated with Immunotherapy and Target Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Treatment-Related Adverse Events (TRAEs) and Their Association with Therapeutic Efficacy

3.2. Circulating Biomarkers

3.2.1. Serum LDH and S100B

3.2.2. Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

3.2.3. Circulating MicroRNAs (miRNAs)

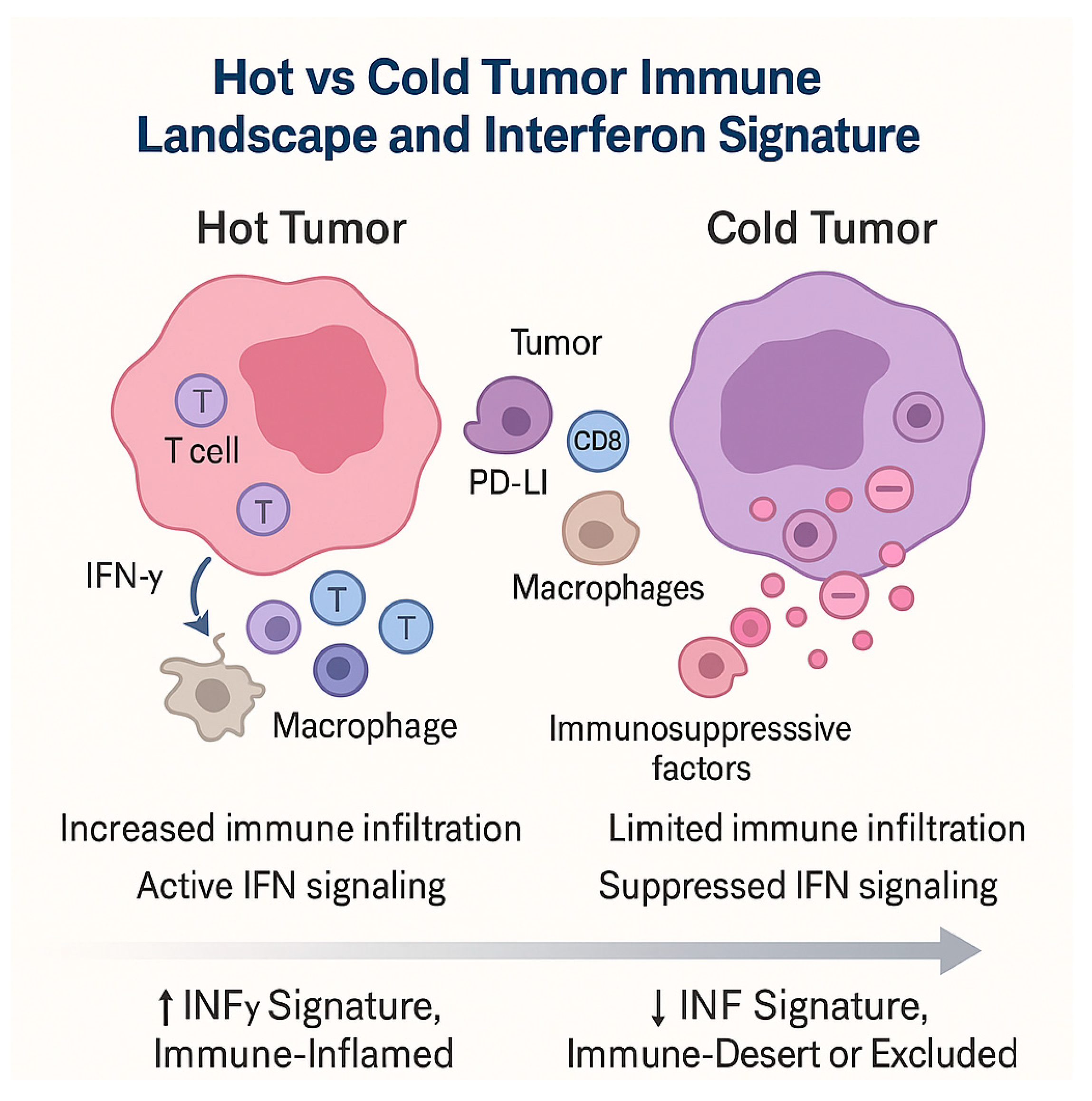

3.3. Hot and Cold Tumors: Interferon Signatures and Immune-Inflamed Phenotypes

- -

- Hot tumors: enriched in IFN-γ-driven transcripts, T cell infiltration, chemokine expression, antigen presentation machinery, and adaptive immune activation—generally more responsive to ICIs.

- -

- Cold tumors: deficient in IFN signature, with limited immune infiltrate, exclusion of effector T cells, and immunosuppressive barriers—often refractory to monotherapy.

- -

- Dynamic conversion: Some tumors initially cold may “heat up” under therapy, with induced IFN signaling and immune infiltration signaling favorable biological response.

- -

- Dualistic roles: IFN signatures can also be modulated by resistance mechanisms (e.g., JAK mutations, chronic IFN exposure, induction of inhibitory pathways), complicating their predictive utility.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| trAEs | treatment-related adverse events |

| irAEs | immune-related adverse events |

| ICIs | immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| ttAEs | Targeted therapy-related adverse events |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| OS | Overall survival |

| ctDNA | circulating tumor DNA |

| NGS | next-generation sequencing |

| ELBS | European Liquid Biopsy Society |

| GEP | gene expression profile |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

References

- Tasdogan, A.; Sullivan, R.J.; Katalinic, A.; Lebbe, C.; Whitaker, D.; Puig, S.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V.; Massi, D.; Schadendorf, D. Cutaneous melanoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2025, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Grossman, D.C.; Curry, S.J.; Owens, D.K.; Barry, M.J.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W.; Kemper, A.R.; et al. Behavioral Counseling to Prevent Skin Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2018, 319, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, U.M.; Kashani-Sabet, M.; Kirkwood, J.M. Cutaneous Melanoma: A Review. JAMA 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, M.; Singh, D.; Laversanne, M.; Vignat, J.; Vaccarella, S.; Meheus, F.; Cust, A.E.; de Vries, E.; Whiteman, D.C.; Bray, F. Global Burden of Cutaneous Melanoma in 2020 and Projections to 2040. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, V.; Venturi, F.; Silvestri, F.; Trane, L.; Savarese, I.; Scarfì, F.; Cencetti, F.; Pecenco, S.; Tramontana, M.; Maio, V.; et al. Atypical Spitz tumours: An epidemiological, clinical and dermoscopic multicentre study with 16 years of follow-up. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dika, E.; Chessa, M.A.; Veronesi, G.; Ravaioli, G.M.; Fanti, P.A.; Ribero, S.; Tripepi, G.; Gurioli, C.; Traniello Gradassi, A.; Lambertini, M.; et al. A single institute’s experience on melanoma prognosis: A long-term follow-up. G. Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 153, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, V.; Magnaterra, E.; Zuccaro, B.; Magi, S.; Magliulo, M.; Medri, M.; Mazzoni, L.; Venturi, F.; Silvestri, F.; Tomassini, G.M.; et al. Is Pediatric Melanoma Really That Different from Adult Melanoma? A Multicenter Epidemiological, Clinical and Dermoscopic Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broseghini, E.; Veronesi, G.; Gardini, A.; Venturi, F.; Scotti, B.; Vespi, L.; Marchese, P.V.; Melotti, B.; Comito, F.; Corti, B.; et al. Defining high-risk patients: Beyond the 8the AJCC melanoma staging system. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 317, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, F.; Magnaterra, E.; Scotti, B.; Ferracin, M.; Dika, E. Predictive Factors for Sentinel Lymph Node Positivity in Melanoma Patients-The Role of Liquid Biopsy, MicroRNA and Gene Expression Profile Panels. Cancers 2025, 17, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dika, E.; Veronesi, G.; Altimari, A.; Riefolo, M.; Ravaioli, G.M.; Piraccini, B.M.; Lambertini, M.; Campione, E.; Gruppioni, E.; Fiorentino, M.; et al. BRAF, KIT, and NRAS Mutations of Acral Melanoma in White Patients. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 153, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, T.; Ottaviano, M.; Arance, A.; Blank, C.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Donia, M.; Dummer, R.; Garbe, C.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Gogas, H.; et al. Cutaneous melanoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, C.; Amaral, T.; Peris, K.; Hauschild, A.; Arenberger, P.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Bastholt, L.; Bataille, V.; Del Marmol, V.; Dréno, B.; et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for melanoma. Part 2: Treatment—Update 2022. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 170, 256–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarfì, F.; Patrizi, A.; Veronesi, G.; Lambertini, M.; Tartari, F.; Mussi, M.; Melotti, B.; Dika, E. The role of topical imiquimod in melanoma cutaneous metastases: A critical review of the literature. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogas, H.; Eggermont, A.M.M.; Hauschild, A.; Hersey, P.; Mohr, P.; Schadendorf, D.; Spatz, A.; Dummer, R. Biomarkers in melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20 (Suppl. S6), vi8–vi13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozzi, F.; Di Raimondo, C.; Lanna, C.; Diluvio, L.; Mazzilli, S.; Garofalo, V.; Dika, E.; Dellambra, E.; Coniglione, F.; Bianchi, L.; et al. Latest Evidence Regarding the Effects of Photosensitive Drugs on the Skin: Pathogenetic Mechanisms and Clinical Manifestations. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indini, A.; Di Guardo, L.; Cimminiello, C.; Prisciandaro, M.; Randon, G.; De Braud, F.; Del Vecchio, M. Immune-related adverse events correlate with improved survival in patients undergoing anti-PD1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-E.; Yang, C.-K.; Peng, M.-T.; Huang, P.-W.; Chang, C.-F.; Yeh, K.-Y.; Chen, C.-B.; Wang, C.-L.; Hsu, C.-W.; Chen, I.-W.; et al. The association between immune-related adverse events and survival outcomes in Asian patients with advanced melanoma receiving anti-PD-1 antibodies. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, J.; Minor, D.; D’Angelo, S.; Neyns, B.; Smylie, M.; Miller, W.H.; Gutzmer, R.; Linette, G.; Chmielowski, B.; Lao, C.D.; et al. Overall Survival in Patients with Advanced Melanoma Who Received Nivolumab Versus Investigator’s Choice Chemotherapy in CheckMate 037: A Randomized, Controlled, Open-Label Phase III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussaini, S.; Chehade, R.; Boldt, R.G.; Raphael, J.; Blanchette, P.; Maleki Vareki, S.; Fernandes, R. Association between immune-related side effects and efficacy and benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2021, 92, 102134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, Z.; Lucas, A.; Liang, S.I.; Yang, E.; Stone, S.; Fadlullah, M.Z.H.; Bayless, N.L.; Marr, S.S.; Thompson, M.A.; Padron, L.J.; et al. Associations between immune checkpoint inhibitor response, immune-related adverse events, and steroid use in RADIOHEAD: A prospective pan-tumor cohort study. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dika, E.; Patrizi, A.; Ribero, S.; Fanti, P.A.; Starace, M.; Melotti, B.; Sperandi, F.; Piraccini, B.M. Hair and nail adverse events during treatment with targeted therapies for metastatic melanoma. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2016, 26, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturi, F.; Veronesi, G.; Scotti, B.; Dika, E. Cutaneous Toxicities of Advanced Treatment for Cutaneous Melanoma: A Prospective Study from a Single-Center Institution. Cancers 2024, 16, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzi, L.; Alessandrini, A.M.; Quaglino, P.; Piraccini, B.M.; Dika, E.; Ribero, S. Cutaneous Events Associated with Immunotherapy of Melanoma: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarfì, F.; Melotti, B.; Veronesi, G.; Ravaioli, G.M.; Baraldi, C.; Lambertini, M.; Patrizi, A.; Dika, E. Sweet syndrome in metastatic melanoma during treatment with dabrafenib and trametinib. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2019, 60, e242–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dika, E.; Lambertini, M.; Gouveia, B.; Mussi, M.; Marcelli, E.; Campione, E.; Gurioli, C.; Melotti, B.; Alessandrini, A.; Ribero, S. Oral Manifestations in Melanoma Patients Treated with Target or Immunomodulatory Therapies. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, V.; Colombo, J.; Trane, L.; Silvestri, F.; Venturi, F.; Zuccaro, B.; Doni, L.; Stanganelli, I.; Covarelli, P. Cutaneous immune-related adverse events and photodamaged skin in patients with metastatic melanoma: Could nicotinamide be useful? Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 1558–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Tanaka, R.; Asami, Y.; Teramoto, Y.; Imamura, T.; Sato, S.; Maruyama, H.; Fujisawa, Y.; Matsuya, T.; Fujimoto, M.; et al. Correlation between vitiligo occurrence and clinical benefit in advanced melanoma patients treated with nivolumab: A multi-institutional retrospective study. J. Dermatol. 2017, 44, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teulings, H.-E.; Limpens, J.; Jansen, S.N.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Reitsma, J.B.; Spuls, P.I.; Luiten, R.M. Vitiligo-like depigmentation in patients with stage III-IV melanoma receiving immunotherapy and its association with survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuya, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Matsushita, S.; Tanaka, R.; Teramoto, Y.; Asami, Y.; Uehara, J.; Aoki, M.; Yamamura, K.; Nakamura, Y.; et al. Vitiligo expansion and extent correlate with durable response in anti-programmed death 1 antibody treatment for advanced melanoma: A multi-institutional retrospective study. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faje, A.T.; Sullivan, R.; Lawrence, D.; Tritos, N.A.; Fadden, R.; Klibanski, A.; Nachtigall, L. Ipilimumab-induced hypophysitis: A detailed longitudinal analysis in a large cohort of patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 4078–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, L.; Ding, Y.; Bai, X.; Sheng, X.; Dai, J.; Chi, Z.; Cui, C.; Kong, Y.; Fan, Y.; Xu, Y.; et al. Overall Survival of Patients With Unresectable or Metastatic BRAF V600-Mutant Acral/Cutaneous Melanoma Administered Dabrafenib Plus Trametinib: Long-Term Follow-Up of a Multicenter, Single-Arm Phase IIa Trial. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 720044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Dai, J.; Li, C.; Cui, C.; Mao, L.; Wei, X.; Sheng, X.; Chi, Z.; Yan, X.; Tang, B.; et al. Risk Models for Advanced Melanoma Patients Under Anti-PD-1 Monotherapy-Ad hoc Analyses of Pooled Data from Two Clinical Trials. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 639085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Pareja, N.; Faje, A.T.; Miller, K.K. The Risk of Adrenal Insufficiency after Treatment with Relatlimab in Combination with Nivolumab is Higher than Expected. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 110, e3827–e3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozeman, E.A.; Hoefsmit, E.P.; Reijers, I.L.M.; Saw, R.P.M.; Versluis, J.M.; Krijgsman, O.; Dimitriadis, P.; Sikorska, K.; van de Wiel, B.A.; Eriksson, H.; et al. Survival and biomarker analyses from the OpACIN-neo and OpACIN neoadjuvant immunotherapy trials in stage III melanoma. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Johnson, D.B. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J.B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z.M.; Benyamin, F.W.; Lei, Y.M.; Jabri, B.; Alegre, M.-L.; et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015, 350, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Xie, W.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Geng, Y.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, Z. Association of Immune Related Adverse Events with Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Overall Survival in Cancers: A Systemic Review and Meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 633032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima Ferreira, J.; Costa, C.; Marques, B.; Castro, S.; Victor, M.; Oliveira, J.; Santos, A.P.; Sampaio, I.L.; Duarte, H.; Marques, A.P.; et al. Improved survival in patients with thyroid function test abnormalities secondary to immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. CII 2021, 70, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, A.M.; Ashworth, M.T.; Swann, S.; Kefford, R.F.; Flaherty, K.; Weber, J.; Infante, J.R.; Kim, K.B.; Gonzalez, R.; Hamid, O.; et al. Characteristics of pyrexia in BRAFV600E/K metastatic melanoma patients treated with combined dabrafenib and trametinib in a phase I/II clinical trial. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schadendorf, D.; Robert, C.; Dummer, R.; Flaherty, K.T.; Tawbi, H.A.; Menzies, A.M.; Banerjee, H.; Lau, M.; Long, G.V. Pyrexia in patients treated with dabrafenib plus trametinib across clinical trials in BRAF-mutant cancers. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 2021, 153, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, C.; Keim, U.; Suciu, S.; Amaral, T.; Eigentler, T.K.; Gesierich, A.; Hauschild, A.; Heinzerling, L.; Kiecker, F.; Schadendorf, D.; et al. Prognosis of Patients With Stage III Melanoma According to American Joint Committee on Cancer Version 8: A Reassessment on the Basis of 3 Independent Stage III Melanoma Cohorts. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2543–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dummer, R.; Ascierto, P.A.; Gogas, H.J.; Arance, A.; Mandala, M.; Liszkay, G.; Garbe, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Krajsova, I.; Gutzmer, R.; et al. Encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma (COLUMBUS): A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzerling, L.; Eigentler, T.K.; Fluck, M.; Hassel, J.C.; Heller-Schenck, D.; Leipe, J.; Pauschinger, M.; Vogel, A.; Zimmer, L.; Gutzmer, R. Tolerability of BRAF/MEK inhibitor combinations: Adverse event evaluation and management. ESMO Open 2019, 4, e000491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Flaherty, K.T.; Robert, C.; Arance, A.; de Groot, J.W.B.; Garbe, C.; Gogas, H.J.; Gutzmer, R.; Krajsová, I.; et al. COLUMBUS 7-year update: A randomized, open-label, phase III trial of encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF V600E/K-mutant melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 2024, 204, 114073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogas, H.J.; Flaherty, K.T.; Dummer, R.; Ascierto, P.A.; Arance, A.; Mandala, M.; Liszkay, G.; Garbe, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Krajsova, I.; et al. Adverse events associated with encorafenib plus binimetinib in the COLUMBUS study: Incidence, course and management. Eur. J. Cancer. 2019, 119, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, V.; Robert, C.; Grob, J.J.; Gogas, H.; Dutriaux, C.; Demidov, L.; Gupta, A.; Menzies, A.M.; Ryll, B.; Miranda, F.; et al. Improved pyrexia-related outcomes associated with an adapted pyrexia adverse event management algorithm in patients treated with adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib: Primary results of COMBI-APlus. Eur. J. Cancer. 2022, 163, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, H.; Rübben, A.; Esser, A.; Araujo, A.; Persa, O.-D.; Leijs, M. A distinct four-value blood signature of pyrexia under combination therapy of malignant melanoma with dabrafenib and trametinib evidenced by an algorithm-defined pyrexia score. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, V.; Scarfì, F.; Silvestri, F.; Maida, P.; Venturi, F.; Trane, L.; Gori, A. Genital piercing: A warning for the risk of vulvar lichen sclerosus. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e14703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dummer, R.; Tsao, H.; Robert, C. How cutaneous eruptions help to understand the mode of action of kinase inhibitors. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 167, 965–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, S.E.; Haigentz, M.; Piperdi, B. Dermatologic Toxicities from Monoclonal Antibodies and Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors against EGFR: Pathophysiology and Management. Chemother. Res. Pract. 2012, 2012, 351210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacouture, M.E.; Duvic, M.; Hauschild, A.; Prieto, V.G.; Robert, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Kim, C.C.; McCormack, C.J.; Myskowski, P.L.; Spleiss, O.; et al. Analysis of dermatologic events in vemurafenib-treated patients with melanoma. Oncologist 2013, 18, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanneste, L.; Wolter, P.; Van den Oord, J.J.; Stas, M.; Garmyn, M. Cutaneous adverse effects of BRAF inhibitors in metastatic malignant melanoma, a prospective study in 20 patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Chen, F.; Zhou, B. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence of dermatological toxicities associated with vemurafenib treatment in patients with melanoma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 44, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.; Karaszewska, B.; Schachter, J.; Rutkowski, P.; Mackiewicz, A.; Stroiakovski, D.; Lichinitser, M.; Dummer, R.; Grange, F.; Mortier, L.; et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacouture, M.E.; Mitchell, E.P.; Piperdi, B.; Pillai, M.V.; Shearer, H.; Iannotti, N.; Xu, F.; Yassine, M. Skin toxicity evaluation protocol with panitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-Emptive Skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Várvölgyi, T.; Janka, E.A.; Szász, I.; Koroknai, V.; Toka-Farkas, T.; Szabó, I.L.; Ványai, B.; Szegedi, A.; Emri, G.; Balázs, M. Combining Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Metastatic Melanoma. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, A.; Wistuba-Hamprecht, K.; Foppen, M.G.; Yuan, J.; Postow, M.A.; Wong, P.; Romano, E.; Khammari, A.; Dreno, B.; Capone, M.; et al. Baseline peripheral blood biomarkers associated with clinical outcome of advanced melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 2908–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.R.; Erickson, L.A.; Ichetovkin, I.; Knauer, D.J.; Markovic, S.N. Circulating Serologic and Molecular Biomarkers in Malignant Melanoma. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keung, E.Z.; Gershenwald, J.E. The eighth edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) melanoma staging system: Implications for melanoma treatment and care. Expert. Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2018, 18, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wilpe, S.; Tolmeijer, S.H.; de Vries, I.J.M.; Koornstra, R.H.T.; Mehra, N. LDH Isotyping for Checkpoint Inhibitor Response Prediction in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. Immuno 2021, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhou, S.; Xiao, Z. Prognostic value of lactate dehydrogenase in patients with uveal melanoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibition. Aging 2023, 15, 8770–8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurisic, V.; Radenkovic, S.; Konjevic, G. The Actual Role of LDH as Tumor Marker, Biochemical and Clinical Aspects. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 867, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolin, B.; Djan, I.; Trifunovic, J.; Dugandzija, T.; Novkovic, D.; Djan, V.; Vucinic, N. MIA, S100 and LDH as important predictors of overall survival of patients with stage IIb and IIc melanoma. J. BUON Off. J. Balk. Union. Oncol. 2016, 21, 691–697. [Google Scholar]

- Gassenmaier, M.; Lenders, M.M.; Forschner, A.; Leiter, U.; Weide, B.; Garbe, C.; Eigentler, T.K.; Wagner, N.B. Serum S100B and LDH at Baseline and During Therapy Predict the Outcome of Metastatic Melanoma Patients Treated with BRAF Inhibitors. Target. Oncol. 2021, 16, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, N.B.; Forschner, A.; Leiter, U.; Garbe, C.; Eigentler, T.K. S100B and LDH as early prognostic markers for response and overall survival in melanoma patients treated with anti-PD-1 or combined anti-PD-1 plus anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, V.; Maida, P.; Salvati, L.; Scarfì, F.; Trane, L.; Gori, A.; Silvestri, F.; Venturi, F.; Covarelli, P. Trauma and foreign bodies may favour the onset of melanoma metastases. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 45, 619–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaskel, P.; Berking, C.; Sander, S.; Volkenandt, M.; Peter, R.U.; Krähn, G. S-100 protein in peripheral blood: A marker for melanoma metastases: A prospective 2-center study of 570 patients with melanoma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999, 41, 962–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauschild, A.; Engel, G.; Brenner, W.; Gläser, R.; Mönig, H.; Henze, E.; Christophers, E. S100B protein detection in serum is a significant prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. Oncology 1999, 56, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipson, E.J.; Velculescu, V.E.; Pritchard, T.S.; Sausen, M.; Pardoll, D.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Diaz, L.A. Circulating tumor DNA analysis as a real-time method for monitoring tumor burden in melanoma patients undergoing treatment with immune checkpoint blockade. J. Immunother. Cancer 2014, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maloberti, T.; De Leo, A.; Coluccelli, S.; Sanza, V.; Gruppioni, E.; Altimari, A.; Comito, F.; Melotti, B.; Marchese, P.V.; Dika, E.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Advanced-Stage Melanomas in Clinical Practice Using a Laboratory-Developed Next-Generation Sequencing Panel. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Pu, H.; Liu, Q.; Guo, Z.; Luo, D. Circulating Tumor DNA—A Novel Biomarker of Tumor Progression and Its Favorable Detection Techniques. Cancers 2022, 14, 6025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchisio, S.; Ricci, A.A.; Roccuzzo, G.; Bongiovanni, E.; Ortolan, E.; Bertero, L.; Berrino, E.; Pala, V.; Ponti, R.; Fava, P.; et al. Monitoring circulating tumor DNA liquid biopsy in stage III BRAF-mutant melanoma patients undergoing adjuvant treatment. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsavela, G.; McEvoy, A.C.; Pereira, M.R.; Reid, A.L.; Al-Ogaili, Z.; Warburton, L.; Khattak, M.A.; Abed, A.; Meniawy, T.M.; Millward, M.; et al. Detection of clinical progression through plasma ctDNA in metastatic melanoma patients: A comparison to radiological progression. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 126, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, L.; Del Regno, L.; Di Stefani, A.; Mannino, M.; Fossati, B.; Catapano, S.; Quattrini, L.; Pellegrini, C.; Cortellini, A.; Parisi, A.; et al. The dynamics of circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) during treatment reflects tumour response in advanced melanoma patients. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 32, 1785–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Long, G.V.; Boyd, S.; Lo, S.; Menzies, A.M.; Tembe, V.; Guminski, A.; Jakrot, V.; Scolyer, R.A.; Mann, G.J.; et al. Circulating tumour DNA predicts response to anti-PD1 antibodies in metastatic melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seremet, T.; Jansen, Y.; Planken, S.; Njimi, H.; Delaunoy, M.; El Housni, H.; Awada, G.; Schwarze, J.K.; Keyaerts, M.; Everaert, H.; et al. Undetectable circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) levels correlate with favorable outcome in metastatic melanoma patients treated with anti-PD1 therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeda, M.M.; Long, G.V.; Garrett, J.; Atkinson, V.; Santinami, M.; Schadendorf, D.; Hauschild, A.; Millward, M.; Mandala, M.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; et al. Clinical validation of droplet digital PCR assays in detecting BRAFV600-mutant circulating tumour DNA as a prognostic biomarker in patients with resected stage III melanoma receiving adjuvant therapy (COMBI-AD): A biomarker analysis from a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, L.; Meniawy, T.M.; Calapre, L.; Pereira, M.; McEvoy, A.; Ziman, M.; Gray, E.S.; Millward, M. Stopping targeted therapy for complete responders in advanced BRAF mutant melanoma. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, A.C.; Pereira, M.R.; Reid, A.; Pearce, R.; Cowell, L.; Al-Ogaili, Z.; Khattak, M.A.; Millward, M.; Meniawy, T.M.; Gray, E.S.; et al. Monitoring melanoma recurrence with circulating tumor DNA: A proof of concept from three case studies. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diefenbach, R.J.; Lee, J.H.; Rizos, H. Monitoring Melanoma Using Circulating Free DNA. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broseghini, E.; Venturi, F.; Veronesi, G.; Scotti, B.; Migliori, M.; Marini, D.; Ricci, C.; Casadei, R.; Ferracin, M.; Dika, E. Exploring the Common Mutational Landscape in Cutaneous Melanoma and Pancreatic Cancer. Pigment. Cell Melanoma Res. 2025, 38, e13210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Leest, P.; Schuuring, E. Critical Factors in the Analytical Work Flow of Circulating Tumor DNA-Based Molecular Profiling. Clin. Chem. 2024, 70, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntzifa, A.; Lianidou, E. Pre-analytical conditions and implementation of quality control steps in liquid biopsy analysis. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2023, 60, 573–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.M.; Borsu, L.; Cankovic, M.; Earle, J.S.L.; Gocke, C.D.; Hameed, M.; Jordan, D.; Lopategui, J.R.; Pullambhatla, M.; Reuther, J.; et al. Recommendations for Cell-Free DNA Assay Validations: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology and College of American Pathologists. J. Mol. Diagn. 2023, 25, 876–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broseghini, E.; Dika, E.; Londin, E.; Ferracin, M. MicroRNA Isoforms Contribution to Melanoma Pathogenesis. Non-Coding RNA 2021, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddeo, M.; Broseghini, E.; Venturi, F.; Vaccari, S.; Corti, B.; Lambertini, M.; Ricci, C.; Fontana, B.; Durante, G.; Pariali, M.; et al. Association of miR-146a-5p and miR-21-5p with Prognostic Features in Melanomas. Cancers 2024, 16, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dika, E.; Riefolo, M.; Porcellini, E.; Broseghini, E.; Ribero, S.; Senetta, R.; Osella-Abate, S.; Scarfì, F.; Lambertini, M.; Veronesi, G.; et al. Defining the Prognostic Role of MicroRNAs in Cutaneous Melanoma. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 2260–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, G.; Broseghini, E.; Comito, F.; Naddeo, M.; Milani, M.; Salamon, I.; Campione, E.; Dika, E.; Ferracin, M. Circulating microRNA biomarkers in melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, G.; Comito, F.; Lambertini, M.; Broseghini, E.; Dika, E.; Ferracin, M. Non-coding RNA dysregulation in skin cancers. Essays Biochem. 2021, 65, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dika, E.; Broseghini, E.; Porcellini, E.; Lambertini, M.; Riefolo, M.; Durante, G.; Loher, P.; Roncarati, R.; Bassi, C.; Misciali, C.; et al. Unraveling the role of microRNA/isomiR network in multiple primary melanoma pathogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Tian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Tu, H.; Wong, A.; Yang, Y. The Roles of MiRNAs (MicroRNAs) in Melanoma Immunotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattore, L.; Costantini, S.; Malpicci, D.; Ruggiero, C.F.; Ascierto, P.A.; Croce, C.M.; Mancini, R.; Ciliberto, G. MicroRNAs in melanoma development and resistance to target therapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 22262–22278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Giménez, J.L.; Saadi, W.; Ortega, A.L.; Lahoz, A.; Suay, G.; Carretero, J.; Pereda, J.; Fatmi, A.; Pallardó, F.V.; Mena-Molla, S. miRNAs Related to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sendra, B.; González-Muñoz, J.F.; Pérez-Debén, S.; Monteagudo, C. The Prognostic Value of miR-125b, miR-200c and miR-205 in Primary Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma Is Independent of BRAF Mutational Status. Cancers 2022, 14, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gui, R.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qian, L.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Exosome-Derived microRNA: Implications in Melanoma Progression, Diagnosis and Treatment. Cancers 2022, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Martino, E.; Gandin, I.; Azzalini, E.; Massone, C.; Pizzichetta, M.A.; Giulioni, E.; Javor, S.; Pinzani, C.; Conforti, C.; Zalaudek, I.; et al. A group of three miRNAs can act as candidate circulating biomarkers in liquid biopsies from melanoma patients. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1180799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristescu, R.; Mogg, R.; Ayers, M.; Albright, A.; Murphy, E.; Yearley, J.; Sher, X.; Liu, X.Q.; Lu, H.; Nebozhyn, M.; et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade–based immunotherapy. Science 2018, 362, eaar3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, M.; Lunceford, J.; Nebozhyn, M.; Murphy, E.; Loboda, A.; Kaufman, D.R.; Albright, A.; Cheng, J.D.; Kang, S.P.; Shankaran, V.; et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2930–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, C.S.; Tsoi, J.; Onyshchenko, M.; Abril-Rodriguez, G.; Ross-Macdonald, P.; Wind-Rotolo, M.; Champhekar, A.; Medina, E.; Torrejon, D.Y.; Shin, D.S.; et al. Conserved Interferon-γ Signaling Drives Clinical Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy in Melanoma. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 500–515.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, F.; Pires da Silva, I.; Johansson, P.A.; Menzies, A.M.; Wilmott, J.S.; Addala, V.; Carlino, M.S.; Rizos, H.; Nones, K.; Edwards, J.J.; et al. Multiomic profiling of checkpoint inhibitor-treated melanoma: Identifying predictors of response and resistance, and markers of biological discordance. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 88–102.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak, P.; Hartman, M.L. Dual role of interferon-gamma in the response of melanoma patients to immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockwell, N.K.; Parker, B.S. Tumor inherent interferons: Impact on immune reactivity and immunotherapy. Cytokine 2019, 118, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versluis, J.M.; Blankenstein, S.A.; Dimitriadis, P.; Wilmott, J.S.; Elens, R.; Blokx, W.A.M.; van Houdt, W.; Menzies, A.M.; Schrage, Y.M.; Wouters, M.W.J.M.; et al. Interferon-gamma signature as prognostic and predictive marker in macroscopic stage III melanoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e008125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.U.; Reijers, I.L.M.; Versluis, J.M.; Menzies, A.M.; Dimitriadis, P.; Wouters, M.W.; Saw, R.P.M.; Klop, W.M.C.; Pennington, T.E.; Bosch, L.J.W.; et al. LBA39 Personalized combination of neoadjuvant domatinostat, nivolumab (NIVO) and ipilimumab (IPI) in stage IIIB-D melanoma patients (pts) stratified according to the interferon-gamma signature (IFN-γ sign): The DONIMI study. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.N.; Warrell, J.; Martinez-Morilla, S.; Gavrielatou, N.; Vathiotis, I.; Yaghoobi, V.; Kluger, H.M.; Gerstein, M.; Rimm, D.L. Spatially Informed Gene Signatures for Response to Immunotherapy in Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 3520–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Liu, J.; Yu, Y.V.; Jin, Y.N. Machine learning-based identification of an immunotherapy-related signature to enhance outcomes and immunotherapy responses in melanoma. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1451103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Type I Interferon Signaling Induces Melanoma Cell-Intrinsic PD-1 and Its Inhibition Antagonizes Immune Checkpoint Blockade|Nature Communications. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-51496-2 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Zhai, H.; Dika, E.; Goldovsky, M.; Maibach, H.I. Tape-stripping method in man: Comparison of evaporimetric methods. Skin. Res. Technol. 2007, 13, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Schilling, B.; Liu, D.; Sucker, A.; Livingstone, E.; Jerby-Arnon, L.; Zimmer, L.; Gutzmer, R.; Satzger, I.; Loquai, C.; et al. Integrative molecular and clinical modeling of clinical outcomes to PD1 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1916–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gide, T.N.; Mao, Y.; Scolyer, R.A.; Long, G.V.; Wilmott, J.S. Tissue-Based Profiling Techniques to Achieve Precision Medicine in Cancer: Opportunities and Challenges in Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 5270–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-García, M.; Rojas-Lechuga, M.J.; Torres Moral, T.; Crespí-Payeras, F.; Bagué, J.; Mateu, J.; Paschalidis, N.; de Souza, V.G.; Podlipnik, S.; Carrera, C.; et al. Integrative Molecular and Immune Profiling in Advanced Unresectable Melanoma: Tumor Microenvironment and Peripheral PD-1+ CD4+ Effector Memory T-Cells as Potential Markers of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splendiani, E.; Besharat, Z.M.; Covre, A.; Maio, M.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; Ferretti, E. Immunotherapy in melanoma: Can we predict response to treatment with circulating biomarkers? Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 256, 108613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgi, V.; Scarfì, F.; Gori, A.; Silvestri, F.; Trane, L.; Maida, P.; Venturi, F.; Covarelli, P. Short-term teledermoscopic monitoring of atypical melanocytic lesions in the early diagnosis of melanoma: Utility more apparent than real. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, e398–e399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinotti, E.; Veronesi, G.; Labeille, B.; Cambazard, F.; Piraccini, B.M.; Dika, E.; Perrot, J.L.; Rubegni, P. Imaging technique for the diagnosis of onychomatricoma. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 1874–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Giorgi, V.; Silvestri, F.; Cecchi, G.; Venturi, F.; Zuccaro, B.; Perillo, G.; Cosso, F.; Maio, V.; Simi, S.; Antonini, P.; et al. Dermoscopy as a Tool for Identifying Potentially Metastatic Thin Melanoma: A Clinical-Dermoscopic and Histopathological Case-Control Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Duin, I.A.J.; Verheijden, R.J.; van Diest, P.J.; Blokx, W.A.M.; El-Sharouni, M.-A.; Verhoeff, J.J.C.; Leiner, T.; van den Eertwegh, A.J.M.; de Groot, J.W.B.; van Not, O.J.; et al. A prediction model for response to immune checkpoint inhibition in advanced melanoma. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 154, 1760–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires da Silva, I.; Ahmed, T.; McQuade, J.L.; Nebhan, C.A.; Park, J.J.; Versluis, J.M.; Serra-Bellver, P.; Khan, Y.; Slattery, T.; Oberoi, H.K.; et al. Clinical Models to Define Response and Survival with Anti-PD-1 Antibodies Alone or Combined With Ipilimumab in Metastatic Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, S.M.; Carpenter, C.; Eccles, M.R. Genomic and Epigenomic Biomarkers of Immune Checkpoint Immunotherapy Response in Melanoma: Current and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, C.W.; Boyle, S.M.; Pyke, R.M.; McDaniel, L.D.; Levy, E.; Navarro, F.C.P.; Mellacheruvu, D.; Zhang, S.V.; Tan, M.; Santiago, R.; et al. Prediction of Immunotherapy Response in Melanoma through Combined Modeling of Neoantigen Burden and Immune-Related Resistance Mechanisms. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4265–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, X. Identifying biomarkers associated with immunotherapy response in melanoma by multi-omics analysis. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 167, 107591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.B.; Al-Bzour, A.N.; Ababneh, O.E.; Abushukair, H.M.; Saeed, A. Genomic and Transcriptomic Predictors of Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Melanoma Patients: A Machine Learning Approach. Cancers 2022, 14, 5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lin, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Feng, F.; Xu, J. Multi-omics-based subtyping of melanoma suggests distinct immune and targeted therapy strategies. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1601243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhini, A.A.; Obermayer, A.; Lee, S.J.; LaFramboise, W.A.; Hodi, F.S.; Karunamurthy, A.D.; Eljilany, I.; Chen, D.-T.; Hwu, P.; El Naqa, I.M.; et al. Integrative Immune Signature of Complementary Circulating and Tumoral Biomarkers Maximizes the Predictive Power of Adjuvant Immunotherapeutic Benefits in High-risk Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 3249–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, C.A.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J.; Long, G.V.; Scolyer, R.A.; Lo, S.N.; Carlino, M.S.; Tsang, V.H.M.; Menzies, A.M. Thyroid Immune-related Adverse Events Following Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Treatment. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e3704–e3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, N.; Bar-Hai, N.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Stoff, R.; Grynberg, S.; Schachter, J.; Frommer-Shapira, R. Exploring the clinical significance of specific immune-related adverse events in melanoma patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Melanoma Res. 2024, 34, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B.; Yu, Y.; Wan, J.; Yu, C.; Sun, Y.; Yu, X.; Liu, R.; Huang, H.; Du, Y.; Hu, W.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced vitiligo: A large-scale real world pharmacovigilance study. Int. J. Cancer 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geisler, A.N.; Phillips, G.S.; Barrios, D.M.; Wu, J.; Leung, D.Y.M.; Moy, A.P.; Kern, J.A.; Lacouture, M.E. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related dermatologic adverse events. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Yang, F.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Guan, X.; Shen, C.; Duma, N.; Vera Aguilera, J.; Chintakuntlawar, A.; et al. Treatment-Related Adverse Events of PD-1 and PD-L1 Inhibitors in Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.J.; Naidoo, J.; Santomasso, B.D.; Lacchetti, C.; Adkins, S.; Anadkat, M.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 4073–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, M.; Loree, J.M.; Kasi, P.M.; Parikh, A.R. Using Circulating Tumor DNA in Colorectal Cancer: Current and Evolving Practices. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2846–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidharla, A.; Rapoport, E.; Agarwal, K.; Madala, S.; Linares, B.; Sun, W.; Chakrabarti, S.; Kasi, A. Circulating Tumor DNA as a Minimal Residual Disease Assessment and Recurrence Risk in Patients Undergoing Curative-Intent Resection with or without Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, Z.; Krinshpun, S.; Kalashnikova, E.; Sudhaman, S.; Ozturk Topcu, T.; Nichols, M.; Martin, J.; Bui, K.M.; Palsuledesai, C.C.; Malhotra, M.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA-based molecular residual disease detection for treatment monitoring in advanced melanoma patients. Cancer 2023, 129, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.A.; Huang, H.J.; Piha-Paul, S.A.; Call, S.G.; Karp, D.D.; Fu, S.; Naing, A.; Subbiah, V.; Pant, S.; Dustin, D.J.; et al. Longitudinal Monitoring of Circulating Tumor DNA to Predict Treatment Outcomes in Advanced Cancers. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, e2100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.K.; Park, B.H. Circulating tumor DNA: Current challenges for clinical utility. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e154941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.W.; Battistone, B.; Bauer, K.M.; Weis, A.M.; Barba, C.; Fadlullah, M.Z.H.; Ghazaryan, A.; Tran, V.B.; Lee, S.-H.; Agir, Z.B.; et al. A microRNA-regulated transcriptional state defines intratumoral CD8+ T cells that respond to immunotherapy. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.Y.; Boyd, S.C.; Diefenbach, R.J.; Rizos, H. Circulating MicroRNAs: Functional biomarkers for melanoma prognosis and treatment. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, T.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, D.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Guo, C.; Zhao, Y.; Han, X. Establishment and experimental validation of an immune miRNA signature for assessing prognosis and immune landscape of patients with colorectal cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 6874–6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitch, B.; Lee, D.Y.; Ding, M.; Martinez-Morilla, S.; Aung, T.N.; Ouerghi, F.; Wang, X.; Wei, W.; Damsky, W.; Sznol, M.; et al. Subsets of IFN Signaling Predict Response to Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Patients with Melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2908–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijers, I.L.M.; Rao, D.; Versluis, J.M.; Menzies, A.M.; Dimitriadis, P.; Wouters, M.W.; Spillane, A.J.; Klop, W.M.C.; Broeks, A.; Bosch, L.J.W.; et al. IFN-γ signature enables selection of neoadjuvant treatment in patients with stage III melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 2023, 220, e20221952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, G.T.; Weiner, L.M.; Atkins, M.B. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e542–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

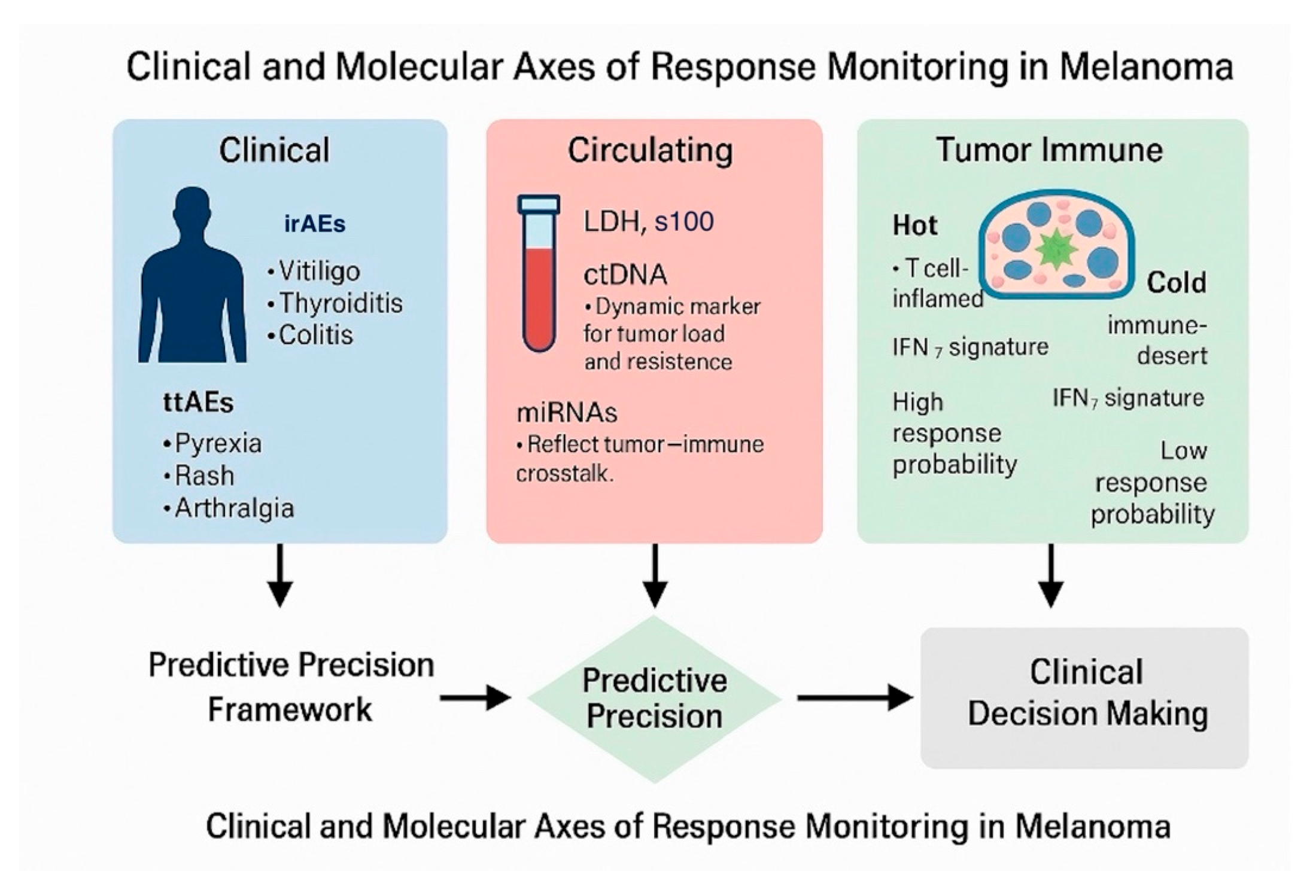

| Step | Process | Key Indicators/Tools | Interpretation/Clinical Action |

| Baseline profiling | Comprehensive clinical and molecular characterization before therapy initiation. | LDH, S100B, baseline ctDNA, miRNA panel (miR-21-5p, miR-146a-5p), PD-L1 IHC, IFN-γ gene-expression profile (GEP), tumor mutational burden (TMB). | Stratify tumors as “hot” (IFN-high, inflamed) or “cold” (immune-desert). Define initial risk and expected treatment sensitivity. |

| Early on-treatment assessment (weeks 4–8) | Initial biological and clinical response evaluation. | Onset and grade of TRAEs (irAEs or ttAEs), repeat ctDNA quantification, miRNA modulation, early imaging if available. | Early ctDNA clearance ± low-grade irAEs → favorable immune activation; persistent ctDNA ± no toxicity → consider intensification or switch. |

| Dynamic monitoring (weeks 8–16) | Continuous assessment of therapeutic efficacy and resistance emergence. | Longitudinal ctDNA kinetics, serial miRNA profiles, cytokine panels, serial IFN-γ GEP measurements. | Declining ctDNA + induced IFN signature → sustained response; rising ctDNA + loss of IFN signature → emerging resistance. |

| Integrative modeling | Multivariate data integration to quantify individualized response probability. | Machine-learning model combining TRAEs, ctDNA, miRNA, LDH, and IFN-γ GEP. | Generates a Response Probability Score (RPS) categorized as high/intermediate/low. |

| Adaptive therapeutic decision | Adjust treatment intensity based on integrated signal. | Compare RPS trajectory with toxicity profile and radiologic data. | High RPS: continue current regimen. Low RPS + no irAEs: escalate (add CTLA-4 blockade or switch). Intermediate RPS: maintain with close follow-up. |

| Validation and feedback loop | Continuous model refinement and prospective data accrual. | Real-world registry data, digital pathology, radiomics integration. | Calibrate thresholds, improve predictive accuracy, and enable AI-assisted decision support for future patients. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Venturi, F.; Magnaterra, E.; Gualandi, A.; Scotti, B.; Baraldi, C.; Alessandrini, A.M.; Veneziano, L.; Cama, E.M.; Melotti, B.; Marchese, P.V.; et al. Toward Personalized Response Monitoring in Melanoma Patients Treated with Immunotherapy and Target Therapy. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3054. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233054

Venturi F, Magnaterra E, Gualandi A, Scotti B, Baraldi C, Alessandrini AM, Veneziano L, Cama EM, Melotti B, Marchese PV, et al. Toward Personalized Response Monitoring in Melanoma Patients Treated with Immunotherapy and Target Therapy. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3054. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233054

Chicago/Turabian StyleVenturi, Federico, Elisabetta Magnaterra, Alberto Gualandi, Biagio Scotti, Carlotta Baraldi, Aurora Maria Alessandrini, Leonardo Veneziano, Elena Maria Cama, Barbara Melotti, Paola Valeria Marchese, and et al. 2025. "Toward Personalized Response Monitoring in Melanoma Patients Treated with Immunotherapy and Target Therapy" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3054. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233054

APA StyleVenturi, F., Magnaterra, E., Gualandi, A., Scotti, B., Baraldi, C., Alessandrini, A. M., Veneziano, L., Cama, E. M., Melotti, B., Marchese, P. V., Tassone, D., Ribero, S., Ardigò, M., & Dika, E. (2025). Toward Personalized Response Monitoring in Melanoma Patients Treated with Immunotherapy and Target Therapy. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3054. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233054