Evaluating GPT-5 for Melanoma Detection Using Dermoscopic Images

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

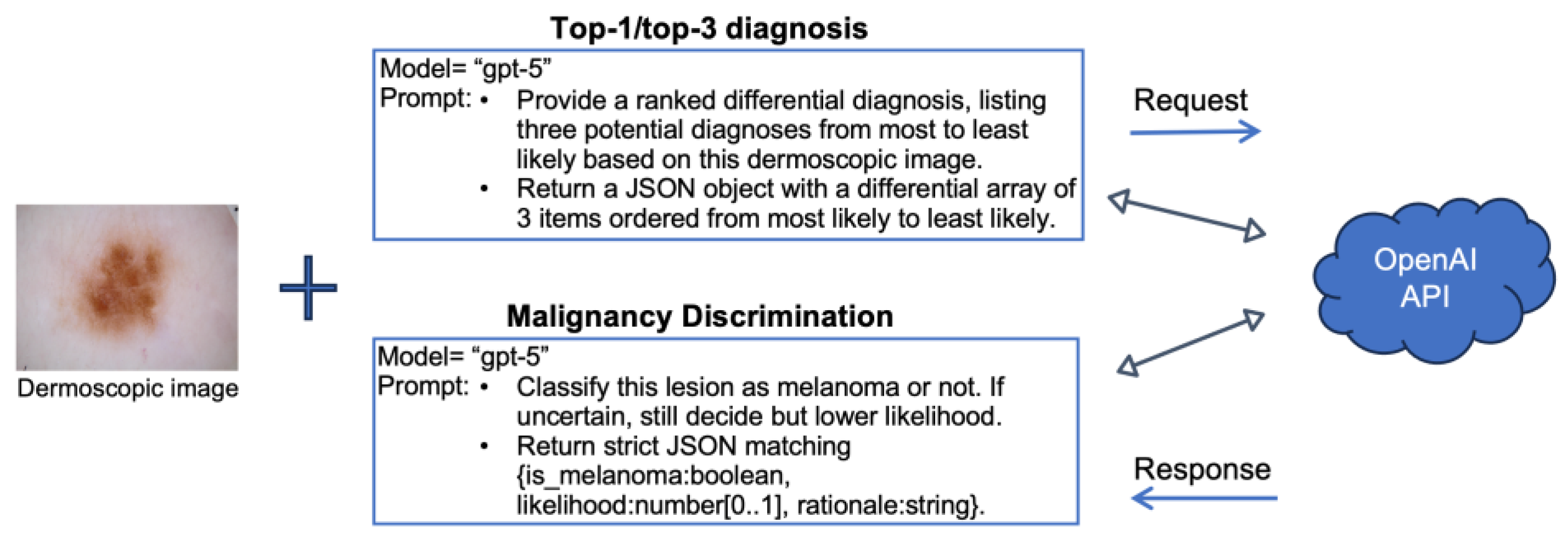

2.2. Diagnostic Tasks and Study Design

2.3. Performance Metrics and Implementation

3. Results

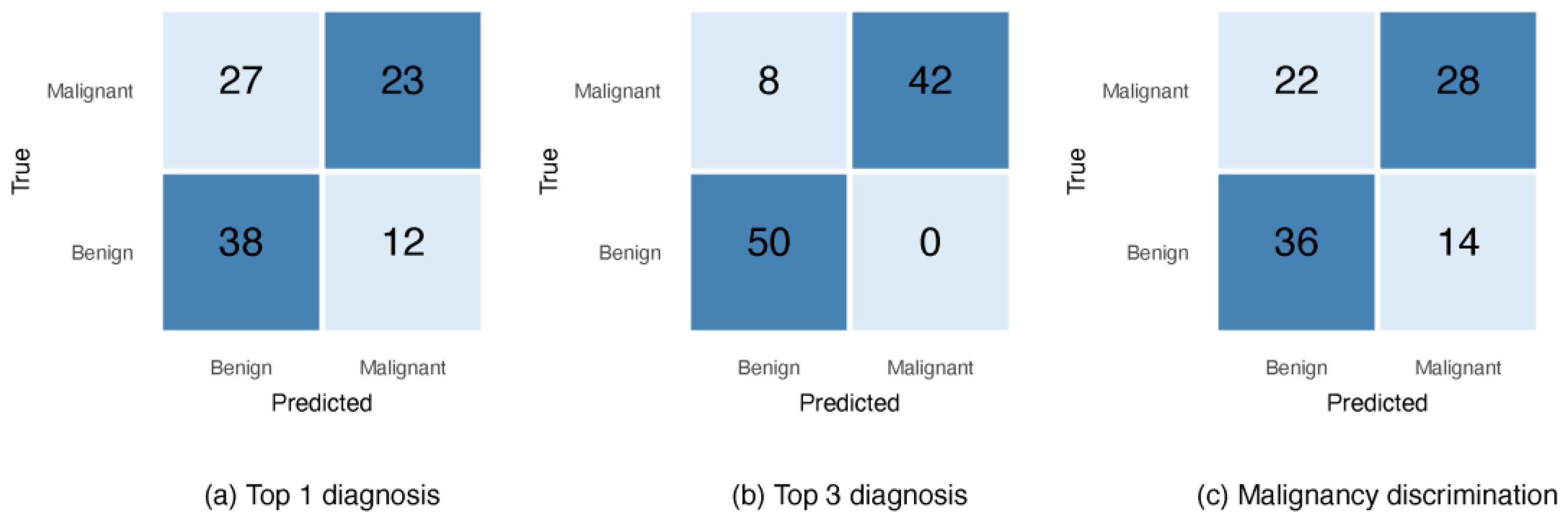

3.1. Evaluating GPT-5 on the ISIC Data

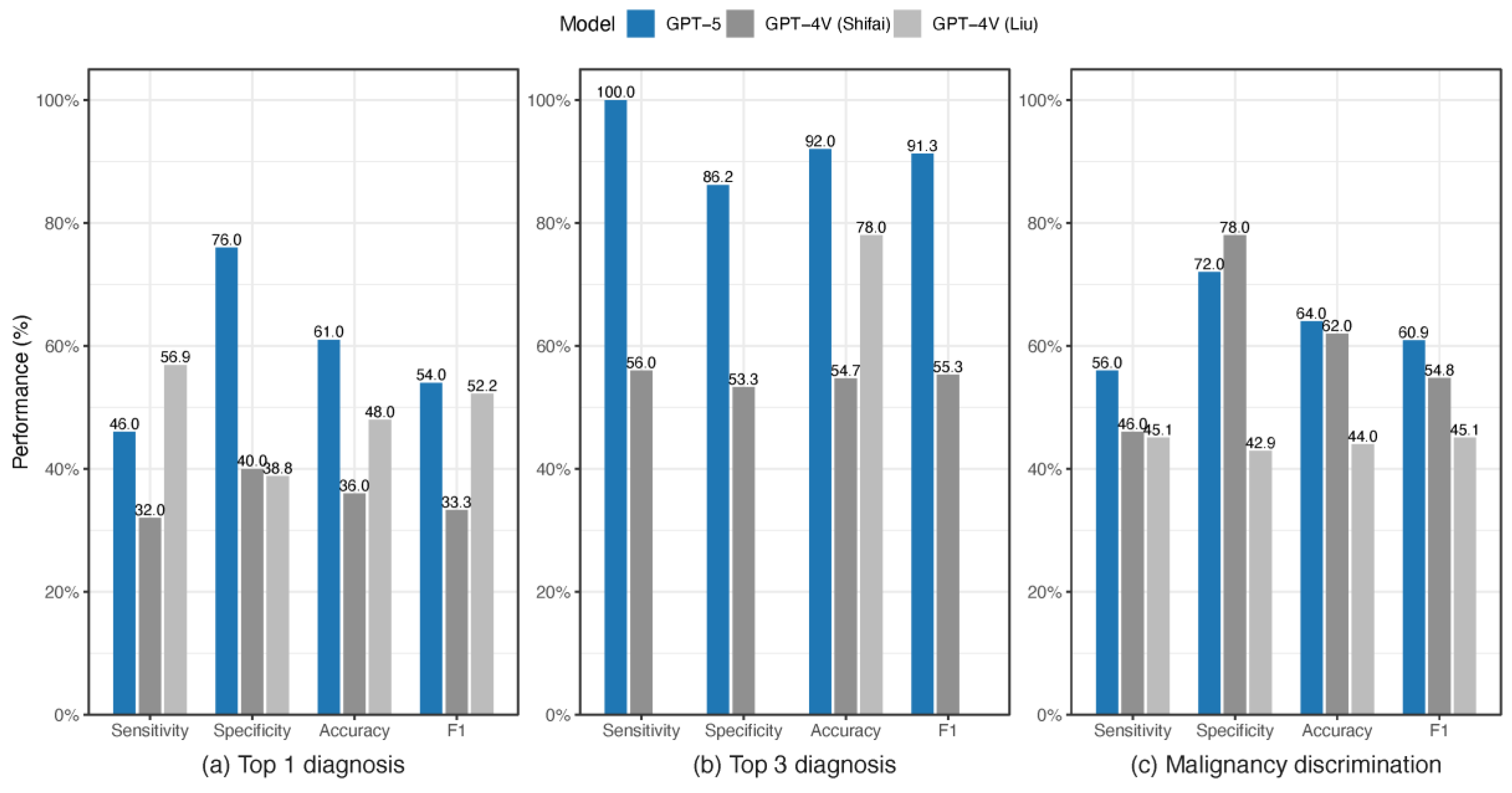

3.2. Comparing GPT-5 with Other Studies on the ISIC Data

3.3. Evaluating GPT-5 on the HAM10K Data

3.4. Comparing GPT-5 with Another Study on HAM10K

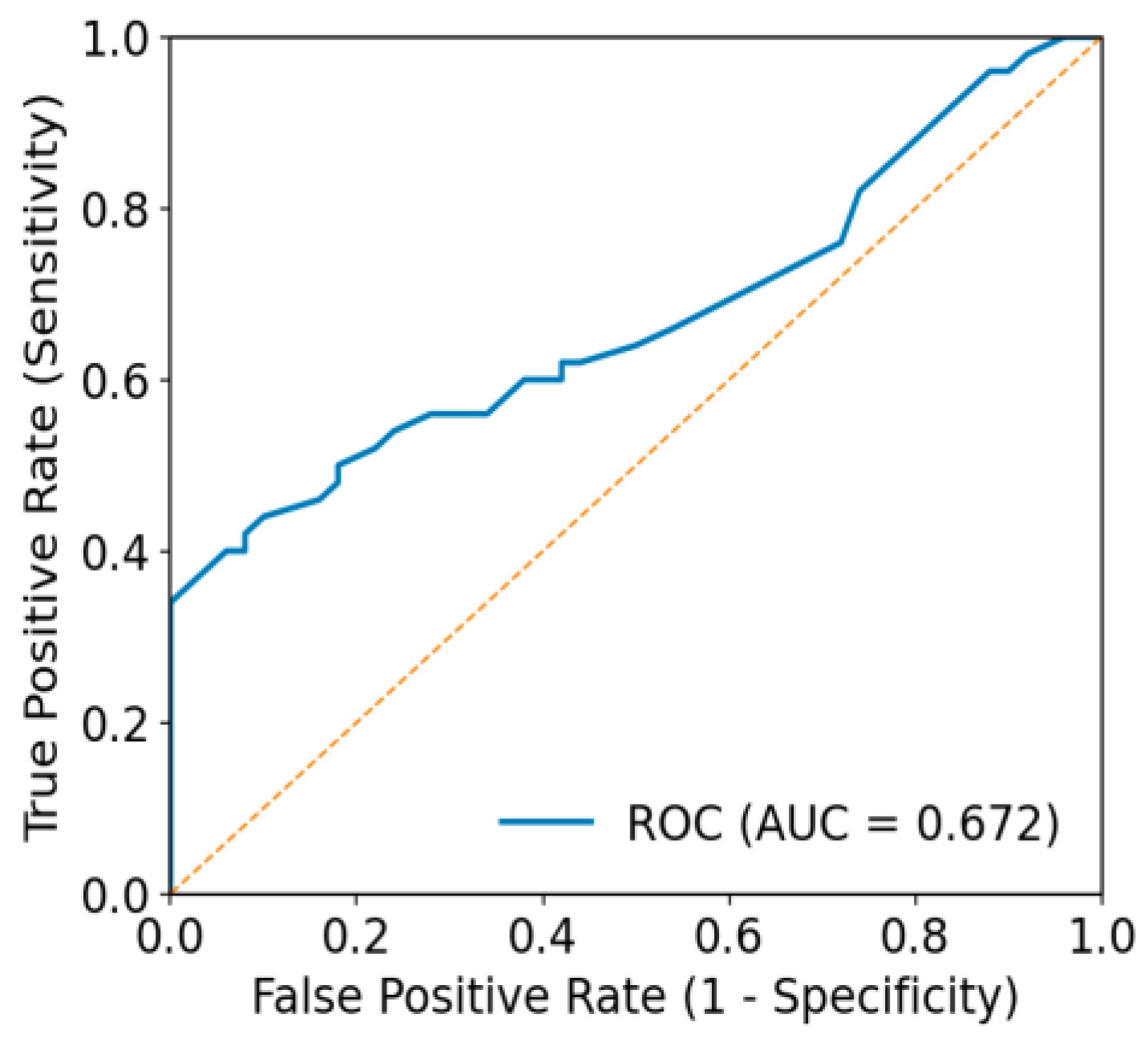

3.5. Agreement Beyond Chance and Threshold-Independent Performance

3.6. Impact of Sampling Temperature on GPT-5 Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| DL | Deep learning |

| EBM | Evidence-Based Medicine |

| GPT | Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| HAM10K | Human Against Machine with 10,000 training images |

| ISIC | International Skin Imaging Collaboration |

| JSON | JavaScript Object Notation |

| LLM | Large language model |

| ML | Machine learning |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

Appendix A.3

References

- Didier, A.J.; Nandwani, S.V.; Watkins, D.; Fahoury, A.M.; Campbell, A.; Craig, D.J.; Vijendra, D.; Parquet, N. Patterns and trends in melanoma mortality in the United States, 1999–2020. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key Statistics for Melanoma Skin Cancer. 2025. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- OpenAI. GPT-5 System Card. 2025. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/gpt-5-system-card.pdf (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Brin, D.; Sorin, V.; Vaid, A.; Soroush, A.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Charney, A.W.; Nadkarni, G.; Klang, E. Comparing ChatGPT and GPT-4 performance in USMLE soft skill assessments. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Scales, N.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, Z.T.; Babayigit, O.; Sen, D.O.; Yarkac, F.U. Performance of ChatGPT in classifying periodontitis according to the 2018 classification of periodontal diseases. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahad, K.; Martin, K.; Amugo, I.; Ferguson, S.; Curtis, A.; Davis, A.; Gangula, P.; Wang, Q. ChatGPT to Enhance Learning in Dental Education at a Historically Black Medical College. Dent. Res. Oral Health 2024, 7, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, B.; Saleh, K.; Alharbi, S.; Alqaderi, H.; Jeong, Y.N. Artificial Intelligence in Periodontology: Performance Evaluation of ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini on the In-service Examination. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, T.H.; Cheatham, M.; Medenilla, A.; Sillos, C.; De Leon, L.; Elepaño, C.; Madriaga, M.; Aggabao, R.; Diaz-Candido, G.; Maningo, J.; et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLoS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, U.; Cohen, E.; Shachar, E.; Somer, J.; Fink, A.; Morse, E.; Shreiber, B.; Wolf, I. GPT versus Resident Physicians—A Benchmark Based on Official Board Scores. NEJM AI 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, C. Chameleon: Mixed-Modal Early-Fusion Foundation Models. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemini. 2025. Available online: https://gemini.google.com/app (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Shahsavar, Y.; Choudhury, A. User Intentions to Use ChatGPT for Self-Diagnosis and Health-Related Purposes: Cross-sectional Survey Study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2023, 10, e47564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marley Presiado, A.M.; Lopes, L.; Hamel, L. KFF Health Misinformation Tracking Poll: Artificial Intelligence and Health Information. 2024. Available online: https://www.kff.org/health-information-and-trust/poll-finding/kff-health-misinformation-tracking-poll-artificial-intelligence-and-health-information/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Gliadkovskaya, A. Some Doctors are Using Public AI Chatbots Like ChatGPT in Clinical Decisions. Is it Safe? Fierce Healthcare. 2024. Available online: https://www.fiercehealthcare.com (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Kuroiwa, T.; Sarcon, A.; Ibara, T.; Yamada, E.; Yamamoto, A.; Tsukamoto, K.; Fujita, K. The Potential of ChatGPT as a Self-Diagnostic Tool in Common Orthopedic Diseases: Exploratory Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e47621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Paluch, R.; Stevens, G.; Müller, C. Exploring patient trust in clinical advice from AI-driven LLMs like ChatGPT for self-diagnosis. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisvarday, S.; Yan, A.; Yarahuan, J.; Kats, D.J.; Ray, M.; Kim, E.; Hong, P.; Spector, J.; Bickel, J.; Parsons, C.; et al. ChatGPT Use Among Pediatric Health Care Providers: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e56797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, E.; Tekin, A.; Ozkan, M.C.; Cabrera, D.; Niven, A.; Dong, Y. Global Health care Professionals’ Perceptions of Large Language Model Use In Practice: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. JMIR Med. Educ. 2025, 11, e58801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifai, N.; Van Doorn, R.; Malvehy, J.; Sangers, T.E. Can ChatGPT vision diagnose melanoma? An exploratory diagnostic accuracy study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 1057–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, S.S.; Chetla, N.; Chen, M.; Hage, T.R.; Chang, J.; Guo, W.Y.; Hugh, J. Evaluating the Diagnostic Accuracy of ChatGPT-4 Omni and ChatGPT-4 Turbo in Identifying Melanoma: Comparative Study. JMIR Dermatol. 2025, 8, e67551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirone, K.; Akrout, M.; Abid, L.; Oakley, A. Assessing the Utility of Multimodal Large Language Models (GPT-4 Vision and Large Language and Vision Assistant) in Identifying Melanoma Across Different Skin Tones. JMIR Dermatol. 2024, 7, e55508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, J.W.; Milkovich, J.; Fremont, S.; Datta, S.; Mosa, A. Beyond the Surface: Assessing GPT-4’s Accuracy in Detecting Melanoma and Suspicious Skin Lesions From Dermoscopic Images. Plast. Surg. 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.; Parappally-Joseph, S.; Kreutz, J.; Traboulsi, D.; Gandhi, M.; Hardin, J. Evaluating the Diagnostic and Treatment Capabilities of GPT-4 Vision in Dermatology: A Pilot Study. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekler, A.; Utikal, J.S.; Enk, A.H.; Solass, W.; Schmitt, M.; Klode, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Sondermann, W.; Franklin, C.; Bestvater, F.; et al. Deep learning outperformed 11 pathologists in the classification of histopathological melanoma images. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 118, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Jain, A.; Eng, C.; Way, D.H.; Lee, K.; Bui, P.; Kanada, K.; De Oliveira Marinho, G.; Gallegos, J.; Gabriele, S.; et al. A deep learning system for differential diagnosis of skin diseases. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musthafa, M.M.; T R, M.; V, V.K.; Guluwadi, S. Enhanced skin cancer diagnosis using optimized CNN architecture and checkpoints for automated dermatological lesion classification. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolakos, D.; Patrick, G.; Geisse, J.K.; Rabinovitz, H.; Buchanan, K.; Hoang, P.; Rodriguez-Diaz, E.; Bigio, I.J.; Cognetta, A.B. Use of an elastic-scattering spectroscopy and artificial intelligence device in the assessment of lesions suggestive of skin cancer: A comparative effectiveness study. JAAD Int. 2024, 14, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, L.; Fakhoury, J.W.; Manwar, R.; Rajabi-Estarabadi, A.; Turk, D.; O’Leary, S.; Fotouhi, A.; Daveluy, S.; Jain, M.; Nouri, K.; et al. Review of Non-Invasive Imaging Technologies for Cutaneous Melanoma. Biosensors 2025, 15, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadafora, M.; Farnetani, F.; Borsari, S.; Kaleci, S.; Porat, D.; Ciardo, S.; Stanganelli, I.; Longo, C.; Pellacani, G.; Scope, A. Clinical, Dermoscopic and Reflectance Confocal Microscopy Characteristics Associated With the Presence of Negative Pigment Network Among Spitzoid Neoplasms. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 34, e70154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlińska, K.; Monist, M.; Sławińska, M.; Popowski, W. Multifocal Oral Mucosal Melanoma with an Atypical Clinical Presentation. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreirinha, A.; Farricha, V.; João, A. [[Artículo traducido]]Diagnóstico de melanoma con fotografía corporal total en 3D. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2025, 116, T1116–T1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pardo Rico, M.; Ginarte Val, M.; Sánchez-Aguilar Rojas, M.D.; Martínez Leboráns, L.; Rodríguez Otero, C.; Flórez, Á. Teledermatology vs. Face-to-Face Dermatology for the Diagnosis of Melanoma: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Pampena, R.; Moscarella, E.; Chester, J.; Starace, M.; Cinotti, E.; Piraccini, B.M.; Argenziano, G.; Peris, K.; Pellacani, G. Dermoscopy of melanoma according to different body sites: Head and neck, trunk, limbs, nail, mucosal and acral. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37, 1718–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P.; Rosendahl, C.; Kittler, H. The HAM10000 dataset, a large collection of multi-source dermatoscopic images of common pigmented skin lesions. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISIC. The International Skin Imaging Collaboration. Available online: https://www.isic-archive.com/ (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Liu, X.; Duan, C.; Kim, M.-K.; Zhang, L.; Jee, E.; Maharjan, B.; Huang, Y.; Du, D.; Jiang, X. Claude 3 Opus and ChatGPT With GPT-4 in Dermoscopic Image Analysis for Melanoma Diagnosis: Comparative Performance Analysis. JMIR Med. Inform. 2024, 12, e59273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, B.R.; Powers, C.M.; Chang, A.; Campbell, C.; Piontkowski, A.J.; Orloff, J.; Levoska, M.A.; Cices, A.; Fenner, J.; Talia, J.; et al. Diagnostic performance of generative pretrained transformer-4 with vision technology versus board-certified dermatologists: A comparative analysis using dermoscopic and clinical images. JAAD Int. 2025, 18, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.C.; Hadidchi, R.; Coard, M.C.; Rubinov, Y.; Alamuri, T.; Liaw, A.; Chandrupatla, R.; Duong, T.Q. Use of Large Language Models on Radiology Reports: A Scoping Review. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2025, S1546-1440(25)00584-8, In press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Model | Diagnostic Objective | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | F1 (%) * | Study ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GPT-5 | Top 1 diagnosis | 46.0 | 76.0 | 61.0 | 54.0 | This Study |

| Top 3 diagnoses | 100 | 86.2 | 92.0 | 91.3 | |||

| Malignancy discrimination | 56.0 | 72.0 | 64.0 | 60.9 | |||

| 2 | GPT-4V | Top 1 diagnosis | 32.0 | 40.0 | 36.0 | 33.3 | Shifai et al. [20] |

| Top 3 diagnoses | 56.0 | 53.3 | 54.7 | 55.3 | |||

| Malignancy discrimination | 46.0 | 78.0 | 62.0 | 54.8 | |||

| 3 | GPT-4V | Top 1 diagnosis | 56.9 | 38.8 | 48.0 | 52.2 | Liu et al. [38] |

| Top 3 diagnoses | 78.0 | ||||||

| Malignancy discrimination | 45.1 | 42.9 | 44.0 | 45.1 |

| No | Model | Diagnostic Objective | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | F1 (%) | Study ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GPT-5 | Top 1 diagnosis | 50.4 | 85.6 | 68.0 | 61.5 | This Study |

| Top 3 diagnoses | 93.2 | 100 | 96.6 | 96.5 | |||

| Malignancy discrimination | 65.1 | 76.8 | 70.9 | 69.1 | |||

| 2 | GPT-4T | Malignancy discrimination | 76.3 | 32.9 | 54.6 | 62.7 | Sattler et al. [21] |

| GPT-4o | Malignancy discrimination | 96.8 | 18.4 | 57.7 | 69.5 |

| Dataset | Diagnostic Objective | Kappa | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISIC | Top 1 diagnosis | 0.220 | 0.535 |

| Malignancy discrimination | 0.280 | 0.672 | |

| HAM10K | Top 1 diagnosis | 0.360 | 0.512 |

| Malignancy discrimination | 0.417 | 0.763 |

| Temperature | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 65.1% | 76.8% | 70.9% | 73.6% | 69.1% |

| 0 | 64.8% | 76.0% | 70.4% | 73.0% | 68.6% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Amugo, I.; Rajakaruna, H.; Irudayam, M.J.; Xie, H.; Shanker, A.; Adunyah, S.E. Evaluating GPT-5 for Melanoma Detection Using Dermoscopic Images. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233052

Wang Q, Amugo I, Rajakaruna H, Irudayam MJ, Xie H, Shanker A, Adunyah SE. Evaluating GPT-5 for Melanoma Detection Using Dermoscopic Images. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(23):3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233052

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qingguo, Ihunna Amugo, Harshana Rajakaruna, Maria Johnson Irudayam, Hua Xie, Anil Shanker, and Samuel E. Adunyah. 2025. "Evaluating GPT-5 for Melanoma Detection Using Dermoscopic Images" Diagnostics 15, no. 23: 3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233052

APA StyleWang, Q., Amugo, I., Rajakaruna, H., Irudayam, M. J., Xie, H., Shanker, A., & Adunyah, S. E. (2025). Evaluating GPT-5 for Melanoma Detection Using Dermoscopic Images. Diagnostics, 15(23), 3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15233052