The Role of Exhaled Breath Analyses in Interstitial Lung Disease

Abstract

1. Background

2. Current Diagnostic Techniques and Their Limitations

3. Technical Aspects of Exhaled Breath Analyses with a Focus on ILD

3.1. Exhaled Breath Condensate

3.2. Exhaled Volatile Organic Compounds

| Principles | Strengths | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exhaled Breath Condensate (EBC) | Involves the collection and analysis of biomarkers within the condensed liquid from exhaled breath. Common biomarkers analysed include pH, hydrogen peroxide (), and non-volatile molecules like cytokines. | Some studies suggest potential clinical value for specific biomarkers (pH, cytokines). | The clinical value is considered limited. Measurements are highly susceptible to confounding factors, including environmental temperature/humidity, food and drink consumption, physical exercise, breathing patterns, and diurnal variability. |

| Exhaled Volatile Organic Compounds (eVOCs) | Involves analysing volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which provide a dynamic reflection of the body’s real-time metabolic state. Analysis can target individual specific compounds or, more commonly, the entire mixture of VOCs (the “breathprint”) using technologies like electronic noses. | Analysing the “breathprint” is considered to have better clinical value than analysing single molecules. Electronic nose technology has shown superior discriminatory ability in distinguishing ILD patients from healthy controls and from other diseases like COPD, asthma, and lung cancer. It has also shown capacity to discriminate between ILD subtypes (e.g., IPF vs. non-IPF) and may have prognostic value, with VOCs correlating to changes in FVC, DLCO, and survival. | Single VOCs rarely represent complex pathologies. The method is highly sensitive to a vast number of confounders, including collection methods (expiratory flow rate, breath hold), breathing patterns, patient demographics (age, sex), lifestyle factors (smoking, diet, exercise), environmental pollution, diurnal variations, medications, oxygen therapy, and chronic comorbidities (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, reflux). Results are also highly dependent on the statistical methods used. |

| Exhaled Nitric Oxide | Measures the concentration of nitric oxide (NO) in exhaled breath. Extended NO analyses (using multiple flow rates) can partition NO production to the central airways (measured as ) or the peripheral/alveolar region (measured as ). | has been found to be increased in some ILD patients (especially CTD-ILD) and showed an inverse relationship with DLCO. It has also shown potential in predicting treatment response. | is affected by age, sex, height, weight, smoking, medications, and diet. |

3.3. Exhaled Nitric Oxide

4. Summary of Studies in ILD

5. Summary of Evidence, Clinical Implications and Agenda for Future Research

5.1. Summary of Evidence

5.2. Clinical Implications

5.3. Agenda for Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maher, T.M.; Bendstrup, E.; Dron, L.; Langley, J.; Smith, G.; Khalid, J.M.; Patel, H.; Kreuter, M. Global incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belloli, E.A.; Beckford, R.; Hadley, R.; Flaherty, K.R. Idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Respirology 2016, 21, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimundo, K.; Solomon, J.J.; Olson, A.L.; Kong, A.M.; Cole, A.L.; Fischer, A.; Swigris, J.J. Rheumatoid Arthritis-Interstitial Lung Disease in the United States: Prevalence, Incidence, and Healthcare Costs and Mortality. J. Rheumatol. 2019, 46, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijsenbeek, M.; Suzuki, A.; Maher, T.M. Interstitial lung diseases. Lancet 2022, 400, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryerson, C.J.; Adegunsoye, A.; Piciucchi, S.; Hariri, L.P.; Nicholson, A.G. Update of the International Multidisciplinary Classification of the Interstitial Pneumonias: An ERS/ATS Statement. Eur. Respir. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, C.R.; Collins, B.F.; Salisbury, M.L. Identification and Remediation of Environmental Exposures in Patients With Interstitial Lung Disease: Evidence Review and Practical Considerations. Chest 2021, 160, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenot, A.P.; Amicosante, M. Metal-induced diffuse lung disease. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 29, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirce, S.; Vandenplas, O.; Campo, P.; Cruz, M.J.; de Blay, F.; Koschel, D.; Moscato, G.; Pala, G.; Raulf, M.; Sastre, J.; et al. Occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis: An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2016, 71, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, P.D.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Balmes, J.R.; Cummings, K.J.; Fishwick, D.; Miedinger, D.; Murgia, N.; Naidoo, R.N.; Reynolds, C.J.; Sigsgaard, T.; et al. The Occupational Burden of Nonmalignant Respiratory Diseases. An Official American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society Statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 1312–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminati, A.; Harari, S. Smoking-related interstitial pneumonias and pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2006, 3, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, G.; Wells, A.U.; du Bois, R.M. Respiratory bronchiolitis associated with interstitial lung disease and desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Clin. Chest Med. 2004, 25, 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaiblmair, M.; Behr, W.; Haeckel, T.; Märkl, B.; Foerg, W.; Berghaus, T. Drug induced interstitial lung disease. Open Respir. Med. J. 2012, 6, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeoch, S.; Weatherley, N.; Swift, A.J.; Oldroyd, A.; Johns, C.; Hayton, C.; Giollo, A.; Wild, J.M.; Waterton, J.C.; Buch, M.; et al. Drug-Induced Interstitial Lung Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira-Avendano, I.; Abril, A.; Burger, C.D.; Dellaripa, P.F.; Fischer, A.; Gotway, M.B.; Lee, A.S.; Lee, J.S.; Matteson, E.L.; Yi, E.S. Interstitial Lung Disease and Other Pulmonary Manifestations in Connective Tissue Diseases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coward, W.R.; Saini, G.; Jenkins, G. The pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2010, 4, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suki, B.; Stamenović, D.; Hubmayr, R. Lung parenchymal mechanics. Compr. Physiol. 2011, 1, 1317–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, F.J.; Collard, H.R.; Pardo, A.; Raghu, G.; Richeldi, L.; Selman, M.; Swigris, J.J.; Taniguchi, H.; Wells, A.U. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, M.; Vašáková, M. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Respir. Res. 2019, 20, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benveniste, M.F.; Gomez, D.; Carter, B.W.; Betancourt Cuellar, S.L.; Shroff, G.S.; Benveniste, A.P.; Odisio, E.G.; Marom, E.M. Recognizing Radiation Therapy-related Complications in the Chest. Radiographics 2019, 39, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ageely, G.; Souza, C.; De Boer, K.; Zahra, S.; Gomes, M.; Voduc, N. The Impact of Multidisciplinary Discussion (MDD) in the Diagnosis and Management of Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Diseases. Can. Respir. J. 2020, 2020, 9026171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, K.R.; King, T.E., Jr.; Raghu, G.; Lynch, J.P., 3rd; Colby, T.V.; Travis, W.D.; Gross, B.H.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Toews, G.B.; Long, Q.; et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia: What is the effect of a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 170, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, J.S.; Morisset, J.; Fisher, J.H.; Churg, A.M.; Bilawich, A.M.; Ellis, J.; English, J.C.; Hague, C.J.; Khalil, N.; Leipsic, J. Role of a Regional Multidisciplinary Conference in the Diagnosis of Interstitial Lung Disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunninghake, G.W.; Lynch, D.A.; Galvin, J.R.; Gross, B.H.; Müller, N.; Schwartz, D.A.; King, T.E., Jr.; Lynch, J.P., III; Hegele, R.; Waldron, J.; et al. Radiologic findings are strongly associated with a pathologic diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest 2003, 124, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Raparia, K.; Lynch, D.A.; Brown, K.K. Surgical Lung Biopsy for Interstitial Lung Diseases. Chest 2017, 151, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, M.E.; Hansen-Flaschen, J.; Ahmad, N.N.; Rossman, M.D.; Kaiser, L.R.; Kucharczuk, J.C.; Shrager, J.B. Complications of video-assisted thoracoscopic lung biopsy in patients with interstitial lung disease. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2007, 83, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaklitsch, M.; Billmeier, S. Preoperative evaluation and risk assessment for elderly thoracic surgery patients. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2009, 19, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, S.D.; Wanger, J.; Zibrak, J.D.; Wencel, M.L.; Burg, C.; Stauffer, J.L. Using forced vital capacity (FVC) in the clinic to monitor patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF): Pros and cons. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2021, 15, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegewald, M.J. Diffusing capacity. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2009, 37, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Miller, M.R.; Thompson, B.; Aliverti, A.; Barjaktarevic, I.; Cooper, B.G.; Culver, B.; Derom, E.; Hall, G.L.; et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, V.N.; Flaherty, K.R.; Toews, G.B.; Colby, T.V.; Travis, W.D.; Long, Q.; Murray, S.; Kazerooni, E.A.; Gross, B.H.; Lynch, J.P., III; et al. Prognostic value of desaturation during a 6-minute walk test in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 168, 1084–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, I.; Barnes, P.J.; Loukides, S.; Sterk, P.J.; Högman, M.; Olin, A.C.; Amann, A.; Antus, B.; Baraldi, E.; Bikov, A.; et al. A European Respiratory Society technical standard: Exhaled biomarkers in lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 49, 1600965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainer, A.; Faverio, P.; Busnelli, S.; Catalano, M.; Della Zoppa, M.; Marruchella, A.; Pesci, A.; Luppi, F. Molecular Biomarkers in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: State of the Art and Future Directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomos, I.; Roussis, I.; Matthaiou, A.M.; Dimakou, K. Molecular and Genetic Biomarkers in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Where Are We Now? Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Del Castillo, A.; Sánchez-Vidaurre, S.; Simeón-Aznar, C.P.; Cruz, M.J.; Fonollosa-Pla, V.; Muñoz, X. Prognostic Role of Exhaled Breath Condensate pH and Fraction Exhaled Nitric Oxide in Systemic Sclerosis Related Interstitial Lung Disease. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2017, 53, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koczulla, A.R.; Noeske, S.; Herr, C.; Dette, F.; Pinkenburg, O.; Schmid, S.; Jörres, R.A.; Vogelmeier, C.; Bals, R. Ambient temperature impacts on pH of exhaled breath condensate. Respirology 2010, 15, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullmann, T.; Barta, I.; Antus, B.; Valyon, M.; Horváth, I. Environmental temperature and relative humidity influence exhaled breath condensate pH. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kullmann, T.; Barta, I.; Antus, B.; Horváth, I. Drinking influences exhaled breath condensate acidity. Lung 2008, 186, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikov, A.; Galffy, G.; Tamasi, L.; Bartusek, D.; Antus, B.; Losonczy, G.; Horvath, I. Exhaled breath condensate pH decreases during exercise-induced bronchoconstriction. Respirology 2014, 19, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikov, A.; Lazar, Z.; Schandl, K.; Antus, B.M.; Losonczy, G.; Horvath, I. Exercise changes volatiles in exhaled breath assessed by an electronic nose. Acta Physiol. Hung. 2011, 98, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fireman, E.; Shtark, M.; Priel, I.E.; Shiner, R.; Mor, R.; Kivity, S.; Fireman, Z. Hydrogen peroxide in exhaled breath condensate (EBC) vs eosinophil count in induced sputum (IS) in parenchymal vs airways lung diseases. Inflammation 2007, 30, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, H.; Becher, G.; Decker, M.; Reinhold, P. Evaluation of H2O2 and pH in exhaled breath condensate samples: Methodical and physiological aspects. Biomark. Biochem. Indic. Expo. Response Susceptibility Chem. 2008, 13, 319–341. [Google Scholar]

- van Beurden, W.J.; Dekhuijzen, P.N.; Harff, G.A.; Smeenk, F.W. Variability of exhaled hydrogen peroxide in stable COPD patients and matched healthy controls. Respir. Int. Rev. Thorac. Dis. 2002, 69, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradi, M.; Acampa, O.; Goldoni, M.; Adami, E.; Apostoli, P.; de Palma, G.; Pesci, A.; Mutti, A. Metallic elements in exhaled breath condensate of patients with interstitial lung diseases. J. Breath Res. 2009, 3, 046003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, E.; Froehler, M.; Degen, M.; Mahavadi, P.; Dartsch, R.C.; Korfei, M.; Ruppert, C.; Seeger, W.; Guenther, A. Exhalative Breath Markers Do Not Offer for Diagnosis of Interstitial Lung Diseases: Data from the European IPF Registry (eurIPFreg) and Biobank. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolla, G.; Fusaro, E.; Nicola, S.; Bucca, C.; Peroni, C.; Parisi, S.; Cassinis, M.C.; Ferraris, A.; Angelino, F.; Heffler, E.; et al. Th-17 cytokines and interstitial lung involvement in systemic sclerosis. J. Breath Res. 2016, 10, 046013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effros, R.M.; Peterson, B.; Casaburi, R.; Su, J.; Dunning, M.; Torday, J.; Biller, J.; Shaker, R. Epithelial lining fluid solute concentrations in chronic obstructive lung disease patients and normal subjects. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 99, 1286–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázár, Z.; Cervenak, L.; Orosz, M.; Gálffy, G.; Komlósi, Z.I.; Bikov, A.; Losonczy, G.; Horváth, I. Adenosine triphosphate concentration of exhaled breath condensate in asthma. Chest 2010, 138, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlata, S.; Finamore, P.; Meszaros, M.; Dragonieri, S.; Bikov, A. The Role of Electronic Noses in Phenotyping Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Biosensors 2020, 10, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, J.H.; Bos, L.D.; Sterk, P.J.; Schultz, M.J.; Fens, N.; Horvath, I.; Bikov, A.; Montuschi, P.; Di Natale, C.; Yates, D.H.; et al. Comparison of classification methods in breath analysis by electronic nose. J. Breath Res. 2015, 9, 046002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Sar, I.G.; van Jaarsveld, N.; Spiekerman, I.A.; Toxopeus, F.J.; Langens, Q.L.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Dauwels, J.; Moor, C.C. Evaluation of different classification methods using electronic nose data to diagnose sarcoidosis. J. Breath Res. 2023, 17, 047104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikov, A.; Paschalaki, K.; Logan-Sinclair, R.; Horváth, I.; Kharitonov, S.A.; Barnes, P.J.; Usmani, O.S.; Paredi, P. Standardised exhaled breath collection for the measurement of exhaled volatile organic compounds by proton transfer reaction mass spectrometry. BMC Pulm. Med. 2013, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantier, L.; Smolinska, A.; Fijten, R.; Flamant, M.; Dallinga, J.; Mercadier, J.J.; Pachen, D.; d’Ortho, M.P.; van Schooten, F.J.; Crestani, B.; et al. The use of exhaled air analysis in discriminating interstitial lung diseases: A pilot study. Respir. Res. 2022, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.J.; Chitwood, C.P.; Xie, Z.; Miller, H.A.; van Berkel, V.H.; Fu, X.A.; Frieboes, H.B.; Suliman, S.A. Disease diagnosis and severity classification in pulmonary fibrosis using carbonyl volatile organic compounds in exhaled breath. Respir. Med. 2024, 222, 107534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragonieri, S.; Brinkman, P.; Mouw, E.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Carratú, P.; Resta, O.; Sterk, P.J.; Jonkers, R.E. An electronic nose discriminates exhaled breath of patients with untreated pulmonary sarcoidosis from controls. Respir. Med. 2013, 107, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragonieri, S.; Scioscia, G.; Quaranta, V.N.; Carratu, P.; Venuti, M.P.; Falcone, M.; Carpagnano, G.E.; Barbaro, M.P.F.; Resta, O.; Lacedonia, D. Exhaled volatile organic compounds analysis by e-nose can detect idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Breath Res. 2020, 14, 047101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moor, C.C.; Oppenheimer, J.C.; Nakshbandi, G.; Aerts, J.; Brinkman, P.; Maitland-van der Zee, A.H.; Wijsenbeek, M.S. Exhaled breath analysis by use of eNose technology: A novel diagnostic tool for interstitial lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Sar, I.G.; Moor, C.C.; Oppenheimer, J.C.; Luijendijk, M.L.; van Daele, P.L.A.; Maitland-van der Zee, A.H.; Brinkman, P.; Wijsenbeek, M.S. Diagnostic Performance of Electronic Nose Technology in Sarcoidosis. Chest 2022, 161, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Sar, I.G.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Braunstahl, G.J.; Loekabino, J.O.; Dingemans, A.C.; In ’t Veen, J.; Moor, C.C. Differentiating interstitial lung diseases from other respiratory diseases using electronic nose technology. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thekedar, B.; Oeh, U.; Szymczak, W.; Hoeschen, C.; Paretzke, H.G. Influences of mixed expiratory sampling parameters on exhaled volatile organic compound concentrations. J. Breath Res. 2011, 5, 016001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, F.; Yue, H.; Wang, J.; Peng, M.; Fan, P.; Qiu, X.; et al. Exploring exhaled volatile organic compounds as potential biomarkers in anti-MDA5 antibody-positive interstitial lung disease. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 480, 4311–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayton, C.; Ahmed, W.; Terrington, D.; White, I.R.; Chaudhuri, N.; Leonard, C.; Wilson, A.M.; Fowler, S.J. Relationship between exhaled volatile organic compounds and lung function change in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax 2025, 80, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanoh, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Motoyoshi, K. Exhaled ethane: An in vivo biomarker of lipid peroxidation in interstitial lung diseases. Chest 2005, 128, 2387–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, E.; Haberer, J.; Maurer, O.; Barreto, G.; Drakopanagiotakis, F.; Degen, M.; Seeger, W.; Guenther, A. Exploring the Ability of Electronic Nose Technology to Recognize Interstitial Lung Diseases (ILD) by Non-Invasive Breath Screening of Exhaled Volatile Compounds (VOC): A Pilot Study from the European IPF Registry (eurIPFreg) and Biobank. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massenet, T.; Potjewijd, J.; Tobal, R.; Gester, F.; Zanella, D.; Henket, M.; Njock, M.S.; Dejong, T.; Gridelet, G.; Giltay, L.; et al. Breathomics to monitor interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis. ERJ Open Res. 2024, 10, 00175–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lechner, M.; Moser, B.; Niederseer, D.; Karlseder, A.; Holzknecht, B.; Fuchs, M.; Colvin, S.; Tilg, H.; Rieder, J. Gender and age specific differences in exhaled isoprene levels. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2006, 154, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.; Greenberg, J.; Cataneo, R.N. Effect of age on the profile of alkanes in normal human breath. Free Radic. Res. 2000, 33, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filipiak, W.; Ruzsanyi, V.; Mochalski, P.; Filipiak, A.; Bajtarevic, A.; Ager, C.; Denz, H.; Hilbe, W.; Jamnig, H.; Hackl, M.; et al. Dependence of exhaled breath composition on exogenous factors, smoking habits and exposure to air pollutants. J. Breath Res. 2012, 6, 036008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krilaviciute, A.; Leja, M.; Kopp-Schneider, A.; Barash, O.; Khatib, S.; Amal, H.; Broza, Y.Y.; Polaka, I.; Parshutin, S.; Rudule, A.; et al. Associations of diet and lifestyle factors with common volatile organic compounds in exhaled breath of average-risk individuals. J. Breath Res. 2019, 13, 026006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragonieri, S.; Quaranta, V.N.; Portacci, A.; Ahroud, M.; Di Marco, M.; Ranieri, T.; Carpagnano, G.E. Effect of Food Intake on Exhaled Volatile Organic Compounds Profile Analyzed by an Electronic Nose. Molecules 2023, 28, 5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotino, V.; Dragonieri, S.; Quaranta, V.N.; Carratu, P.; Ranieri, T.; Resta, O. Influence of circadian rhythm on exhaled breath profiling by electronic nose. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32, 1261–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, D.; Bikov, A.; Losonczy, G.; Murakozy, G.; Horvath, I. Follow up of lung transplant recipients using an electronic nose. J. Breath Res. 2013, 7, 017117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, P.; Ahmed, W.M.; Gómez, C.; Knobel, H.H.; Weda, H.; Vink, T.J.; Nijsen, T.M.; Wheelock, C.E.; Dahlen, S.E.; Montuschi, P.; et al. Exhaled volatile organic compounds as markers for medication use in asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1900544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondo, P.; Scioscia, G.; Di Marco, M.; Quaranta, V.N.; Campanino, T.; Palmieri, G.; Portacci, A.; Santamato, A.; Lacedonia, D.; Carpagnano, G.E.; et al. Electronic Nose Analysis of Exhaled Breath Volatile Organic Compound Profiles during Normoxia, Hypoxia, and Hyperoxia. Molecules 2024, 29, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cikach, F.S., Jr.; Dweik, R.A. Cardiovascular biomarkers in exhaled breath. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012, 55, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khokhar, M. Non-invasive detection of renal disease biomarkers through breath analysis. J. Breath Res. 2024, 18, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekha, S.; Suchetha, M. Recent Advancements and Future Prospects on E-Nose Sensors Technology and Machine Learning Approaches for Non-Invasive Diabetes Diagnosis: A Review. IEEE Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 14, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timms, C.; Thomas, P.S.; Yates, D.H. Detection of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) in patients with obstructive lung disease using exhaled breath profiling. J. Breath Res. 2012, 6, 016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATS/ERS. ATS/ERS recommendations for standardized procedures for the online and offline measurement of exhaled lower respiratory nitric oxide and nasal nitric oxide. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 171, 912–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweik, R.A.; Boggs, P.B.; Erzurum, S.C.; Irvin, C.G.; Leigh, M.W.; Lundberg, J.O.; Olin, A.C.; Plummer, A.L.; Taylor, D.R.; American Thoracic Society Committee on Interpretation of Exhaled Nitric Oxide Levels (FENO) for Clinical Applications. An official ATS clinical practice guideline: Interpretation of exhaled nitric oxide levels (FENO) for clinical applications. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 184, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, R.E.; Gugnani, M.K.; Abrams, J.; Mayes, M.D. Partitioning of alveolar and conducting airway nitric oxide in scleroderma lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 1587–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiev, K.P.; Cabane, J.; Aubourg, F.; Kettaneh, A.; Ziani, M.; Mouthon, L.; Duong-Quy, S.; Fajac, I.; Guillevin, L.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T. Severity of scleroderma lung disease is related to alveolar concentration of nitric oxide. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 30, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiev, K.P.; Le-Dong, N.N.; Duong-Quy, S.; Hua-Huy, T.; Cabane, J.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T. Exhaled nitric oxide, but not serum nitrite and nitrate, is a marker of interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2009, 20, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameli, P.; Bargagli, E.; Bergantini, L.; Refini, R.M.; Pieroni, M.; Sestini, P.; Rottoli, P. Evaluation of multiple-flows exhaled nitric oxide in idiopathic and non-idiopathic interstitial lung disease. J. Breath Res. 2019, 13, 026008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toumpanakis, D.; Karagiannis, K.; Paredi, P.; Bikov, A.; Bonifazi, M.; Lota, H.K.; Kalsi, H.; Minelli, C.; Dikaios, N.; Kastis, G.A.; et al. Contribution of Peripheral Airways Dysfunction to Poor Quality of Life in Sarcoidosis. Chest 2025, 168, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázár, Z.; Kelemen, A.; Gálffy, G.; Losonczy, G.; Horváth, I.; Bikov, A. Central and peripheral airway nitric oxide in patients with stable and exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Breath Res. 2018, 12, 036017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaugg, M.T.; Engler, A.; Bregy, L.; Nussbaumer-Ochsner, Y.; Eiffert, L.; Bruderer, T.; Zenobi, R.; Sinues, P.; Kohler, M. Molecular breath analysis supports altered amino acid metabolism in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2019, 24, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameli, P.; Bargagli, E.; Bergantini, L.; d’Alessandro, M.; Pieroni, M.; Fontana, G.A.; Sestini, P.; Refini, R.M. Extended Exhaled Nitric Oxide Analysis in Interstitial Lung Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Lou, Y.; Zhu, F.; Wang, X.; Wu, W.; Wu, X. Utility of fractional exhaled nitric oxide in interstitial lung disease. J. Breath Res. 2021, 15, 036004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilleminault, L.; Saint-Hilaire, A.; Favelle, O.; Caille, A.; Boissinot, E.; Henriet, A.C.; Diot, P.; March-Adam, S. Can exhaled nitric oxide differentiate causes of pulmonary fibrosis? Respir. Med. 2013, 107, 1789–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozij, N.K.; Granton, J.T.; Silkoff, P.E.; Thenganatt, J.; Chakravorty, S.; Johnson, S.R. Exhaled Nitric Oxide in Systemic Sclerosis Lung Disease. Can. Respir. J. 2017, 2017, 6736239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuttge, D.M.; Bozovic, G.; Hesselstrand, R.; Aronsson, D.; Bjermer, L.; Scheja, A.; Tufvesson, E. Increased alveolar nitric oxide in early systemic sclerosis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2010, 28, S5–S9. [Google Scholar]

- Tiev, K.P.; Coste, J.; Ziani, M.; Aubourg, F.; Cabane, J.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T. Diagnostic value of exhaled nitric oxide to detect interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. Off. J. WASOG 2009, 26, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Tiev, K.P.; Rivière, S.; Hua-Huy, T.; Cabane, J.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T. Exhaled NO predicts cyclophosphamide response in scleroderma-related lung disease. Nitric Oxide Biol. Chem. 2014, 40, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer-Pargada, D.; Amado, C.A.; Abascal-Bolado, B.; Mena, S.T.; Lecue, P.A.; Armiñanzas, C.; de Las Revillas, F.A.; Santibáñez, M.; Agüero, J.; Lobo, V.F.; et al. FeNO as a biomarker of interstitial and fibrotic pulmonary sequelae in patients admitted for severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, K.; Hirano, T.; Suetake, R.; Ohata, S.; Yamaji, Y.; Ito, K.; Edakuni, N.; Matsunaga, K. Exhaled nitric oxide measurements in patients with acute-onset interstitial lung disease. J. Breath Res. 2017, 11, 036001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottin, V.; Hirani, N.A.; Hotchkin, D.L.; Nambiar, A.M.; Ogura, T.; Otaola, M.; Skowasch, D.; Park, J.S.; Poonyagariyagorn, H.K.; Wuyts, W.; et al. Presentation, diagnosis and clinical course of the spectrum of progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. Rev. Off. J. Eur. Respir. Soc. 2018, 27, 180076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.Y.; Peng, H.Y.; Chang, C.J.; Chen, P.C. Diagnostic accuracy of breath tests for pneumoconiosis using an electronic nose. J. Breath Res. 2017, 12, 016001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Sar, I.G.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Dumoulin, D.W.; Jager, A.; van der Veldt, A.A.; Rossius, M.J.; Dingemans, A.M.; Moor, C.C. Detection of Drug-induced Interstitial Lung Disease Caused by Cancer Treatment Using Electronic Nose Exhaled Breath Analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2024, 21, 989–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marges, E.R.; van der Sar, I.G.; de Vries-Bouwstra, J.K.; Huizinga, T.W.; van Daele, P.L.; Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Moor, C.C.; Geelhoed, J.M. Detection of Systemic Sclerosis-associated Interstitial Lung Disease by Exhaled Breath Analysis Using Electronic Nose Technology. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 512–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.I.; Yamada, G.; Otsuka, M.; Nishikiori, H.; Ikeda, K.; Umeda, Y.; Ohnishi, H.; Kuronuma, K.; Chiba, H.; Baumbach, J.I.; et al. Volatile Organic Compounds in Exhaled Breath of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis for Discrimination from Healthy Subjects. Lung 2017, 195, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Exhaled Biomarker | Study Population | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameli et al., 2019 | FENO at multiple flow-rates (50–100–150 and 350 mL · ), CANO and JawNO. | ILD: 134 (IPF: 50, NSIP: 19, HP: 19, CTD-ILD: 46), HC: 60 | CANO and FENO 150 and 350 mL · were significantly higher in ILD patients (median ≥ 10 ppb) than HC (5 ppb), with the exception of FENO 350 mL · in HP (−8 ppb) vs. HC. CANO was inversely correlated with FVC and DLCO. ROC-AUC for CANO in discriminating CTD-ILD from all others was 0.795, with a optimal cut-point of 13 ppb. | [84] |

| Guilleminault et al., 2013 | FENO at 50 mL · | ILD: 61 (IPF: 18, CTD-ILD: 22, HP: 13, DIILD: 8) | Median FENO was 51 ppb (IQR 36-74) in HP, significantly higher than other ILDS. ROC-AUC in discriminating HP from other ILDs was 0.85. | [90] |

| Ferrer-Pargada et al., 2025 | FENO at 50 mL · | COVID-19 pneumonia with oxygen requirements and need of follow-up for diffuse interstitial lung disease: 335 | FENO was higher in patients with interstitial lung sequelae (median 24 ppb) than in patients without (median 20 ppb). ROC-AUC in discriminating patients with lung sequelae was 0.63 (95%CI 0.57–0.69). | [95] |

| Girgis et al., 2002 | FENO at multiple flow-rates (50–100–150 and 200 mL · ), CANO and JawNO. | SSc: 20 (with ILD: 15, with PH: 5), HC: 20 | CANO was increased and JawNO was reduced in SSc versus HC. There was a negative correlation between CANO and DLCO among the patients with SSc (r = −0.66). | [81] |

| Kozij et al., 2017 | FENO at multiple flow-rates (50–100–150–200 and 250 mL · ), CANO and JawNO. | SSc: 35 (Without ILD and PH: 16, With ILD and without PH: 12, With ILD and PH: 7), HC: 25, SLE-PH: 6, Idiopathic PH: 9 | JawNO was reduced in ILD patients (median 1009 ppb) than in HC (median 1342 ppb), without significant differences in CANO. | [91] |

| Oishi et al., 2017 | FENO at 50 mL · and CANO. | Acute onset ILD: Eos. pneumonia: 18, COP: 16, Sarcoidosis: 5, HP: 3 | FENO value of patients with EP (48.1 ppb) was significantly higher than that of the other groups. ROC-AUC in discriminating Eos.pneumonia from other ILDs was 0.90 for FENO and 0.85 for CANO. | [96] |

| Zheng et al., 2021 | FENO at 50 mL · | ILD: 95 (Dermatomyositis-assoc. CTD-ILD: 69, Sjögren’s-assoc. CTD-ILD: 7, Mixed CTD-ILD: 9, IPF: 5, HP: 5), CTD without ILD: 82, HC: 24 | FENO did not significantly differ between ILD and HC and among ILD subgroups. | [89] |

| Wuttge et al., 2010 | CANO | Early onset SSc: 34, HC: 26 | CANO was higher in patients with SSc (median 3–3.5 ppb) versus HC (median 2 ppb), but did not differ between SSc with and without ILD. CANO did not correlate with pulmonary function tests. | [92] |

| Tiev et al., 2009 | FENO at multiple flow-rates (50–100–150 and 200 mL · ) and CANO. | SSc: 65 (with ILD: 38, without ILD: 27) | CANO is higher in SSc with ILD. A cut-off level of 4.3 ppb has a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 59% in discriminating SSc with from without ILD. | [93] |

| Tiev et al., 2007 | FENO at multiple flow-rates (50–100–150 and 200 mL · ) and CANO. | SSc: 58 (with ILD: 33, without ILD: 25), HC: 19 | CANO was higher in SSc versus HC, and higher in SSc with ILD (median 7.5 ppb) versus without ILD (median 4.9 ppb). CANO was inversely correlated with TLC (r = −0.34) and DLCO (r = −0.37). | [82] |

| Tiev et al., 2014 | FENO at multiple flow-rates (50–100–150 and 200 mL · ) and CANO. | SSc treated with 6 courses of cyclophosphamide: 19 | 6 out of 7 patients with baseline CANO > 8.5 ppb had an improvement in FVC or TLC > 10% from baseline versus 3 out of 12. | [94] |

| Krauss et al., 2019 | FENO at 50 mL · , PGE2 and 8-Isoprostan in EBC and BALF. | ILD: 34 (IPF: 11, RB-ILD: 2, COP: 8, HP: 5, Sarcoidosis: 3, CTD-ILD: 3, Indeterminate ILD: 2), COPD: 24, Lung cancer: 16, HC: 20 | No meaningful differences between FENO or eicosanoid values in EBC and BALF of the different cohorts as well as HC. | [64] |

| Guillen-Del Castillo et al., 2017 | FENO at 50 mL · , exhaled CO, pH, nitrite, nitrate and IL-6 in EBC. PFTs performed annually for 4 years. | SSc: 35 (with ILD: 12, without ILD: 23) | The pH and FENO were lower in patients showing a functional decline or death. The ROC-AUC in predicting functional decline or death was 0.65 (95%CI 0.41–0.89) for pH, and 0.81 (95%CI 0.65–0.96) for FENO. No difference for other substances. | [35] |

| Study | Study Population | E-Nose/Type of Discriminant Analysis | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Sar et al., 2023 | ILD: 161, Asthma: 65, COPD: 50, Lung cancer: 46 | SpiroNose. Training and testing (PLS-DA) set. Training and testing groups were obtained using function “sample” in R. | ROC-AUC in discriminating ILD from all other diseases of 0.99 (95% CI 0.97–1.00) in the test set. AUC of 1.00 (95% CI 1.00–1.00) for asthma, AUC of 0.96 (95% CI 0.90–1.00) for COPD, and AUC of 0.98 (95% CI 0.94–1.00) for lung cancer in test sets. | [59] |

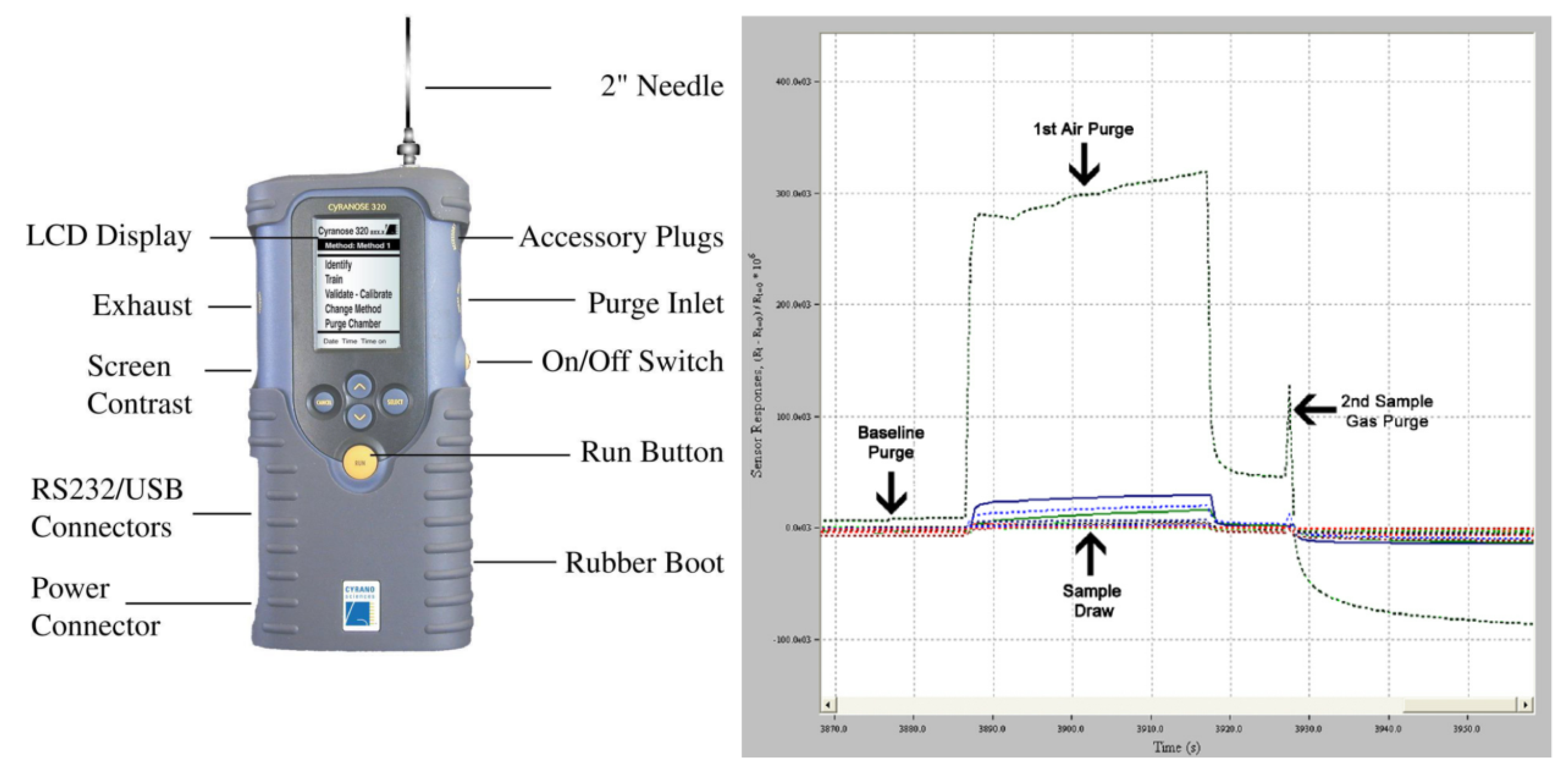

| Dragonieri et al., 2020 | Training: IPF: 32, COPD: 33, HC: 36. Testing: IPF: 10, COPD: 10, HC: 10. | Cyranose320. Training (PCA+LDA) and testing on an independent validation cohort. | IPF vs. COPD vs. healthy controls: CVA 96.7% in external validation. There is a correlation between BALF total cell count and both Principal Components 1 and 2. | [56] |

| Krauss et al., 2019 | ILD: 174 (COP: 28, IPF: 51, HP: 20, CTD-ILD: 25, Sarcoidosis: 19), COPD: 23, HC: 33 | Aeonose. A software program called Aethena was used for pre-processing, data compression, and neural networking. | IPF vs. HC: AUC 0.95, MCC 0.73; COP vs. HC: AUC 0.89, MCC 0.67; CTD-ILD vs. HC: AUC 0.90, MCC 0.69. Other ILD were not discriminated from HC. IPF vs. COP: AUC 0.82, MCC 0.49; IPF vs. CTD-ILD: AUC 0.84, MCC 0.55; CTD-ILD vs. COP: AUC 0.75, MCC 0.40. | [64] |

| Van der Sar et al., 2022 | Sarcoidosis: 252, ILD: 317 (IPF: 124, CTD-ILD: 64, HP: 50), HC: 48 | SpiroNose. Random assignment (2:1) in training and testing (PLS-DA) set. | Sarcoidosis VS HC testing set: 1.00 (independent from sarcoidosis pulmonary involvement, multiple organ involvement, and immunosuppressive treatment). Sarcoidosis VS ILD testing set: AUC of 0.87 (95%CI, 0.82–0.93). Sarcoidosis VS HP testing set: AUC of 0.88 (95%CI, 0.75–1.00). | [58] |

| Van der Sar et al., 2023 | Sarcoidosis: 252, ILD: 317 | SpiroNose. Comparison of various statistical methods. | A classification model with feature selection and random forest classifier showed the highest accuracy (87.1%). | [51] |

| Van der Sar et al., 2024 | DIILD: 20, HC: 20 | SpiroNose. Random assignment (2:1) in training and testing (PLS-DA) set. | ROC-AUC DIILD vs. HC: 0.81 (95% CI 0.67–0.95). The ROC-AUC was higher in DIILD without corticosteroids (0.87) than in DIILD with corticosteroids (0.80). | [99] |

| Yang et al., 2017 | Pneumoconiosis: 34, HC: 64 | Cyranose 320. Random assignment (80%/20%) in training (LDA) and testing set. | Pneumoconiosis vs. HC testing set: AUC 0.86. Sensitivity and specificity were 66.7% and 71.4%, respectively. Results are not influenced by smoking and gender. | [98] |

| Moor et al., 2021 | ILD: 322 (Sarcoidosis: 141, IPF: 85, CTD-ILD: 33, HP: 25, Idiopathic NSIP: 10, IPAF: 11, Other: 17), HC: 48 | SpiroNose. PLS-DA, with a training and testing set obtained using function ’sample’ in R. | ILD vs. HC training and testing set: AUC 1.00. IPF versus non-IPF ILDs: training AUC 0.91 (0.85–0.96), testing AUC 0.87 (0.77–0.96). | [57] |

| Marges et al., 2024 | SSc: with ILD: 110, Without ILD: 113 | SpiroNose. PLS-DA, with a training and testing set (ratio 2:1). | SSc-ILD vs. SSc no ILD: training AUC 0.79 (0.72–0.87), testing AUC 0.84 (0.75–0.94). No impact of immunosuppressant use, disease duration and severity was found. | [100] |

| Yamada et al., 2017 | IPF: 40, HC: 55 | Multi-capillary column and ion mobility spectrometer. | Acetoin, p-cymene, isoprene, ethylbenzene and an unknown compound were significantly different in IPF than in HC, with the first being correlated with pulmonary function tests. | [101] |

| Gaugg et al., 2019 | IPF: 21, HC: 21 | Secondary electrospray ionisation–mass spectrometry (SESI-MS). 1 million 10-fold cross-validations. | Significantly elevated levels of alanine, proline, valine, leucine/isoleucine and 4-hydroxyproline in the EBC of IPF patients. ROC-AUC in discriminating IPF from HC: 0.84 (95%CI 0.78–0.88). | [87] |

| Plantier et al., 2022 | ILD: 104 (IPF: 53, CTD-ILD: 51), HC: 51 | Gas chromatograph time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Random Forest with training/testing set (80%/20%). | The AUC in discriminating IPF from HC, CTD-ILD from HC and IPF from CTD-ILD was 91.2%, 83.9%, and 83.8%, respectively. Positive correlation between VOCs and TLC and 6MWD. | [53] |

| Hayton et al., 2025 | IPF: 57 | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. LASSO regression model. | 63 VOCs associated with a change in FVC and 28 with DLCO. VOCs associated with survival. | [62] |

| Massenet et al., 2024 | SSc: with ILD: 21, Without ILD: 21 | Gas chromatography high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry. PLS-DA on 9 VOCs. | ROC-AUC in discriminating SSc-ILD vs. SSc no ILD: 0.82. | [65] |

| Taylor et al., 2024 | IPF: 12, CTD-ILD: 13 | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometer. PLS-DA, with a training and testing set. | Testing ROC-AUC in discriminating IPF from CTD-ILD of 0.88. ROC-AUC in disease severity: 0.82 (DLCO), 0.90 (FEV1) and 0.87 (FVC), respectively. | [54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Finamore, P.; Marinelli, A.; Scarlata, S.; Dragonieri, S.; Bikov, A. The Role of Exhaled Breath Analyses in Interstitial Lung Disease. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2884. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222884

Finamore P, Marinelli A, Scarlata S, Dragonieri S, Bikov A. The Role of Exhaled Breath Analyses in Interstitial Lung Disease. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(22):2884. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222884

Chicago/Turabian StyleFinamore, Panaiotis, Alessio Marinelli, Simone Scarlata, Silvano Dragonieri, and Andras Bikov. 2025. "The Role of Exhaled Breath Analyses in Interstitial Lung Disease" Diagnostics 15, no. 22: 2884. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222884

APA StyleFinamore, P., Marinelli, A., Scarlata, S., Dragonieri, S., & Bikov, A. (2025). The Role of Exhaled Breath Analyses in Interstitial Lung Disease. Diagnostics, 15(22), 2884. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222884