Gallbladder Schwannoma: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

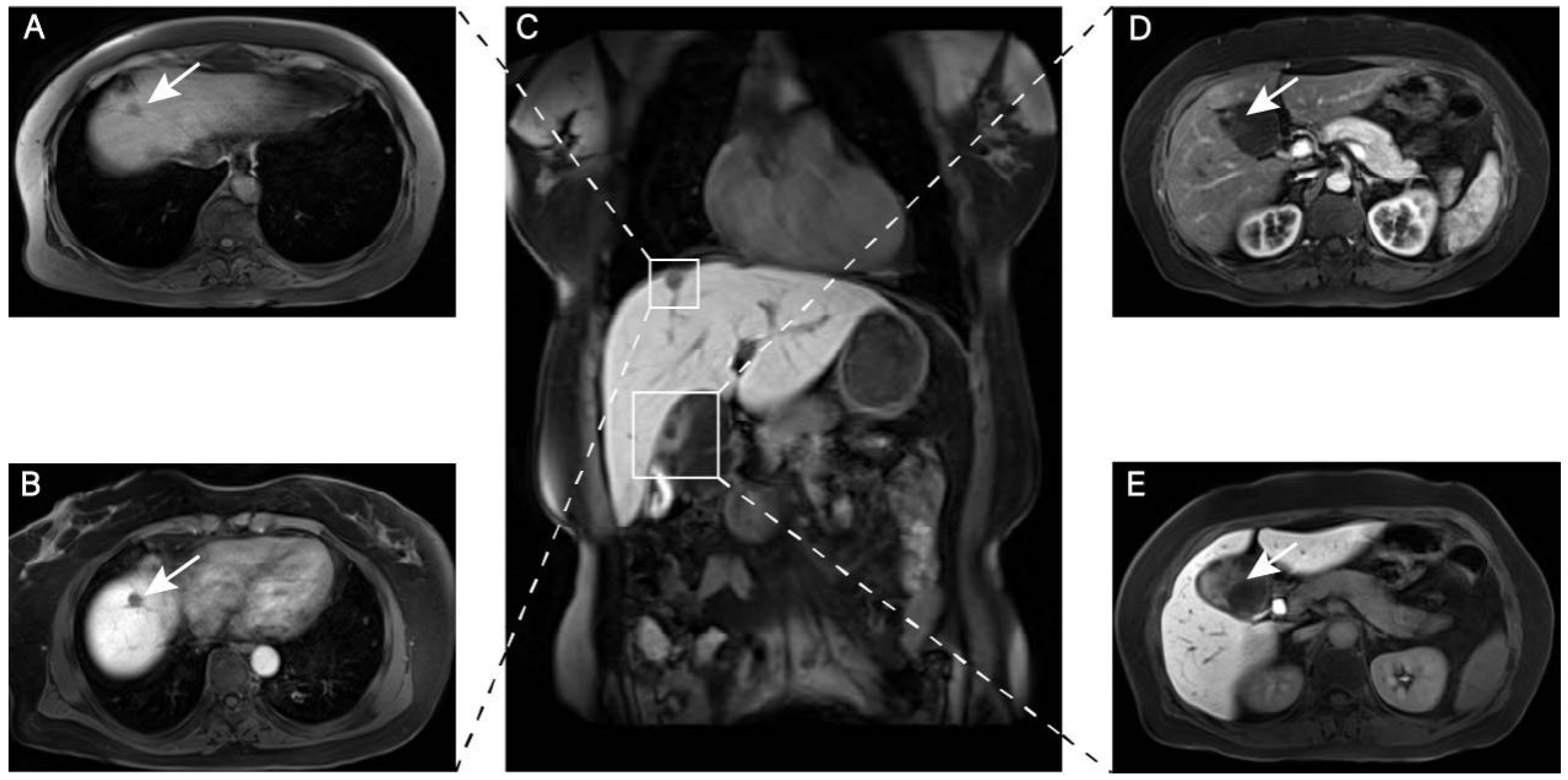

2. Case Report

3. Differential Diagnosis

3.1. Preoperative Differential Diagnosis of HLPD Versus HCC

3.2. Preoperative Differential Diagnosis of Gallbladder Schwannoma Versus Gallbladder Cystadenoma

4. Discussion

4.1. Pathogenesis of Gallbladder Schwannoma

4.1.1. NF2 Gene Mutation and Abnormal Molecular Signaling Pathways

PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway

Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling

Hippo Pathway

4.1.2. Germline Mutations

4.1.3. Tumor Microenvironment

4.2. General Characteristics of Gallbladder Schwannoma

4.2.1. Clinical Manifestations of Gallbladder Schwannoma

4.2.2. Imaging Features of Gallbladder Schwannoma

4.2.3. Pathological Features of Gallbladder Schwannoma

4.3. Histopathological Classification of Schwannomas

4.3.1. Classic Schwannoma

4.3.2. Ancient Schwannoma

4.3.3. Cellular Schwannoma

4.3.4. Plexiform Schwannoma

4.3.5. Epithelioid Schwannoma

4.3.6. Microcystic/Reticular Schwannoma

4.4. Prognosis of Gallbladder Schwannomas

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| DWI | Diffusion-Weighted Imaging |

| ADC | Apparent Diffusion Coefficient |

| NF2 | Neurofibromatosis Type 2 |

| HLPD | Hepatic Lymphoproliferative Disorder |

| TME | The Tumor Microenvironment |

| TAM | Tumor-Associated Macrophage |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Gulati, R.; Hanson, J.A.; Parasher, G.; Castresana, D. Getting the gist of a schwannoma. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 91, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenoglio, L.; Severini, S.; Cena, P.; Migliore, E.; Bracco, C.; Pomero, F.; Panzone, S.; Cavallero, G.B.; Silvestri, A.; Brizio, R.; et al. Common bile duct schwannoma: A case report and review of literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 1275–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pilavaki, M.; Chourmouzi, D.; Kiziridou, A.; Skordalaki, A.; Zarampoukas, T.; Drevelengas, A. Imaging of peripheral nerve sheath tumors with pathologic correlation: Pictorial review. Eur. J. Radiol. 2004, 52, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teranishi, Y.; Miyawaki, S.; Nakatomi, H.; Ohara, K.; Hongo, H.; Dofuku, S.; Okano, A.; Takayanagi, S.; Ota, T.; Yoshimura, J.; et al. Early prediction of functional prognosis in neurofibromatosis type 2 patients based on genotype-phenotype correlation with targeted deep sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picry, A.; Bonne, N.X.; Ding, J.; Aboukais, R.; Lejeune, J.P.; Baroncini, M.; Dubrulle, F.; Vincent, C. Long-term growth rate of vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis 2: A volumetric consideration. Laryngoscope 2016, 126, 2358–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.J.; Hruban, R.H.; Fishman, E.K. Abdominal schwannomas: Review of imaging findings and pathology. Abdom. Radiol. 2017, 42, 1864–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mita, J.; Maeda, T.; Tsujita, E.; Yugawa, K.; Takaki, S.; Tsuji, K.; Hashimoto, N.; Fujikawa, R.; Ono, Y.; Sakai, A.; et al. A case of difficult-to-diagnose hepatic reactive lymphoid hyperplasia finally diagnosed by using PCR analysis of IgH-gene rearrangements: A case report. Int. Cancer Conf. J. 2023, 13, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubé, C.; Oberti, F.; Lonjon, J.; Pageaux, G.; Seror, O.; N’Kontchou, G.; Rode, A.; Radenne, S.; Cassinotto, C.; Vergniol, J.; et al. EASL and AASLD recommendations for the diagnosis of HCC to the test of daily practice. Liver Int. 2017, 37, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Solís, M.L.; de la Serna, S.; Espejo Domínguez, J.M.; Ortega Medina, L. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver. Rev. Esp. Patol. 2019, 52, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, C.; Zhou, G.; Zeng, M.; Xu, P. Hepatic pseudolymphoma: Imaging features on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging. Abdom. Radiol. 2018, 43, 2288–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, A.; Vilana, R.; Ayuso, C.; Bianchi, L.; Solé, M.; Ayuso, J.R.; Boix, L.; Sala, M.; Varela, M.; Llovet, J.M.; et al. Diagnosis of hepatic nodules 20 mm or smaller in cirrhosis: Prospective validation of the noninvasive diagnostic criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2008, 47, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangiovanni, A.; Manini, M.A.; Iavarone, M.; Romeo, R.; Forzenigo, L.V.; Fraquelli, M.; Massironi, S.; Della Corte, C.; Ronchi, G.; Rumi, M.G.; et al. The diagnostic and economic impact of contrast imaging techniques in small HCC in cirrhosis. Gut 2010, 59, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdemir, F.; Baskiran, A. The Importance of AFP in Liver Transplantation for HCC. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2020, 51, 1127–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.J.; Ho, C.T.; Lee, P.C.; Chen, S.C.; Liu, C.A.; Chou, S.C.; Lee, I.C.; Huang, Y.H.; Luo, J.C.; Hou, M.C.; et al. PIVKA-II as a prognostic marker in HCC patients with normal AFP levels. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajiri, T.; Hayashi, H.; Higashi, T.; Yamao, T.; Takematsu, T.; Uemura, N.; Yamamura, K.; Imai, K.; Yamashita, Y.I.; Baba, H. Coexisting schwannoma of the gallbladder and sarcoidosis: A case report. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 6, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, V.Y.; Fletcher, C.D. Epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: Clinicopathologic analysis of 63 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015, 39, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averbukh, L.D.; Wu, D.C.; Cho, W.C.; Wu, G.Y. Biliary Mucinous Cystadenoma: A Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2019, 7, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, B.K.; Alimchandani, M.; Mehta, G.U.; Dewan, R.; Nesvick, C.L.; Miettinen, M.; Heiss, J.D.; Asthagiri, A.R.; Quezado, M.; Germanwala, A.V. Tumors displaying hybrid schwannoma and neurofibroma features in NF2 patients. Clin. Neuropathol. 2016, 35, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, B.; Alwan, J.S.; El Hout, W.; Koussa, K.; El Annan, T.; Noun, D.; Zaghal, A. Neurofibromatosis Type 2 presenting as symptomatic gallbladder hydrops. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2024, 2024, 7680840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbing, D.L.; Schulz, A.; Morrison, H. Pathomechanisms in schwannoma development and progression. Oncogene 2020, 39, 5421–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Wu, Y.Y.; Cai, X.Y.; Fang, W.L.; Xiao, F.L. Molecular diagnosis of neurofibromatosis by multigene panel testing. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 603195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, I.; Hanemann, C.O.; Karplus, P.A.; Bretscher, A. The tumor suppressor merlin controls growth in its open state, and phosphorylation converts it to a less-active state. Dev. Cell 2012, 22, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.; Guan, H.; Zhou, R.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, S.; Venkat Ramani, M.K.; et al. Induced phase separation of mutant NF2 imprisons the cGAS-STING machinery to abrogate antitumor immunity. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 4147–4164.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welling, D.B.; Lasak, J.M.; Akhmametyeva, E.; Ghaheri, B.; Chang, L.S. cDNA microarray analysis of vestibular schwannomas. Otol. Neurotol. 2002, 23, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, C.; Paglino, C.; Mosca, A. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in cancer. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, N.; Sonenberg, N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes. Dev. 2004, 18, 1926–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlashi, R.; Sun, F.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, G. The molecular biology of NF2/Merlin on tumorigenesis and development. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Rindtorff, N.; Boutros, M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene 2017, 36, 1461–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, C.D.; Avalos, L.; Liu, S.J.; Chen, Z.; Zakimi, N.; Casey-Clyde, T.; Bisignano, P.; Lucas, C.G.; Stevenson, E.; Choudhury, A.; et al. MerlinS13 phosphorylation regulates meningioma Wnt signaling. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ercolano, E.; Ammoun, S.; Schmid, M.C.; Barczyk, M.A.; Hanemann, C.O. Merlin-deficient human tumors show loss of contact inhibition and activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling linked to the PDGFR/Src and Rac/PAK pathways. Neoplasia 2011, 13, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, E.E.; Nakai, Y.; Hennigan, R.F.; Ratner, N.; Zheng, Y. NF2-deficient cells depend on the Rac1-canonical Wnt signaling pathway to promote the loss of contact inhibition of proliferation. Oncogene 2010, 29, 2540–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, Y.K.; Murray, L.B.; Houshmandi, S.S.; Xu, Y.; Gutmann, D.H.; Yu, Q. Merlin is a potent inhibitor of glioma growth. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 5733–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, G.H.; Gallagher, R.; Shetler, J.; Skele, K.; Altomare, D.A.; Pestell, R.G.; Jhanwar, S.; Testa, J.R. The NF2 tumor suppressor gene product, merlin, inhibits cell proliferation and cell cycle progression by repressing cyclin D1 expression. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 2384–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colciago, A.; Melfi, S.; Giannotti, G.; Bonalume, V.; Ballabio, M.; Caffino, L.; Fumagalli, F.; Magnaghi, V. Tumor suppressor Nf2/merlin drives Schwann cell changes following electromagnetic field exposure through Hippo-dependent mechanisms. Cell Death Discov. 2015, 1, 15021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.X.; Guan, K.L. The Hippo pathway: Regulators and regulations. Genes. Dev. 2013, 27, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, W.H.; Dieu-Nosjean, M.C.; Pagès, F.; Cremer, I.; Damotte, D.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Galon, J. The immune microenvironment of human tumors: General significance and clinical impact. Cancer Microenviron. 2013, 6, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin, S.R.; Blakeley, J.O.; Evans, D.G.; Hanemann, C.O.; Hulsebos, T.J.; Hunter-Schaedle, K.; Kalpana, G.V.; Korf, B.; Messiaen, L.; Papi, L.; et al. Update from the 2011 International Schwannomatosis Workshop: From genetics to diagnostic criteria. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2013, 161, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, K.V.; Bowes, J.; Rowlands, C.F.; Perez-Becerril, C.; van der Meer, C.M.; King, A.T.; Rutherford, S.A.; Pathmanaban, O.N.; Hammerbeck-Ward, C.; Lloyd, S.K.W.; et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies a susceptibility locus for sporadic vestibular schwannoma at 9p21. Brain 2023, 146, 2861–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, T.; Miyawaki, S.; Teranishi, Y.; Ohara, K.; Hirano, Y.; Ogawa, S.; Torazawa, S.; Sakai, Y.; Hongo, H.; Ono, H.; et al. Current molecular understanding of central nervous system schwannomas. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, A.; Xie, J.; Liu, Y.F.; Poplawski, A.B.; Gomes, A.R.; Madanecki, P.; Fu, C.; Crowley, M.R.; Crossman, D.K.; Armstrong, L.; et al. Germline loss-of-function mutations in LZTR1 predispose to an inherited disorder of multiple schwannomas. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.M.N.; Deng, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Wang, J.; Rao, R.; Xu, L.; Zhou, W.; Choi, K.; Rizvi, T.A.; et al. Programming of Schwann Cells by Lats1/2-TAZ/YAP signaling drives malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 292–308.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisic, D.; Chin, C.R.; Meydan, C.; Teater, M.; Tsialta, I.; Mlynarczyk, C.; Chadburn, A.; Wang, X.; Sarkozy, M.; Xia, M.; et al. ARID1A orchestrates SWI/SNF-mediated sequential binding of transcription factors with ARID1A loss driving pre-memory B cell fate and lymphomagenesis. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 583–604.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, C.J.; Lewis, D.; O’Leary, C.; Waqar, M.; Brough, D.; Couper, K.N.; Dyer, D.P.; Vail, A.; Heal, C.; Macarthur, J.; et al. Increased circulating chemokines and macrophage recruitment in growing vestibular schwannomas. Neurosurgery 2023, 92, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.; Donofrio, C.A.; O’Leary, C.; Li, K.L.; Zhu, X.; Williams, R.; Djoukhadar, I.; Agushi, E.; Hannan, C.J.; Stapleton, E.; et al. The microenvironment in sporadic and NF2-related vestibular schwannoma: A comparative study. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 134, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L. Exploring the role of inflammatory genes and immune infiltration in vestibular schwannomas pathogenesis. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 8335–8353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Shao, W.; Liu, Q.; Lu, Q.; Gu, A.; Jiang, Z. Single cell RNA-sequencing reveals a murine gallbladder cell transcriptome atlas during cholesterol gallstone formation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 714271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugano, R.; Ramachandran, M.; Dimberg, A. Tumor angiogenesis: Causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 1745–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, M.; Briaire-de Bruijn, I.; Malessy, M.J.; de Bruïne, S.F.; van der Mey, A.G.; Hogendoorn, P.C. Tumor-associated macrophages are related to volumetric growth of vestibular schwannomas. Otol. Neurotol. 2013, 34, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, R.; Hirata, Y.; Oneyama, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Kawahara, Y.; Kitamura, M.; Goto, M.; Sekikawa, K.; Takenoshita, S. Schwannoma of the gallbladder: Report of a case. Fukushima J. Med. Sci. 2010, 56, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jakobs, R.; Albert, J.; Schilling, D.; Nuesse, T.; Riemann, J.F. Schwannoma of the common bile duct: A rare cause of obstructive jaundice. Endoscopy 2003, 35, 695–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.N.; Xu, H.X.; Zheng, S.G.; Sun, L.P.; Guo, L.H.; Wu, J. Solitary schwannoma of the gallbladder: A case report and literature review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 6685–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.Y.; Guo, H.; Shen, Y.; Sun, K.; Xie, H.Y.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, S.S.; Wang, W.L. Multiple schwannomas synchronously occurring in the porta hepatis, liver, and gallbladder: First case report. Medicine 2016, 95, e4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.X.; Liu, Z.M.; Fu, Y.Y.; Jia, Q.B. Unsuspected schwannomas of the gallbladder. Dig. Liver Dis. 2018, 50, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bakker, J.K.; Witteveen, E.; van den Bergh, J.; Daams, F. Ancient schwannoma of the gallbladder. ACG Case Rep. J. 2020, 7, e00330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.H.; Yuan, W.B.; Yan, Q.; Mao, J.; Zhang, Q. An accidental gallbladder schwannoma misdiagnosed as malignant cancer. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2023, 22, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.H.; Kim, T.H.; You, S.S.; Choi, S.P.; Min, H.J.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, O.J.; Ko, G.H. Benign schwannoma of the liver: A case report. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2008, 23, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, S.W.; Langloss, J.M.; Enzinger, F.M. Value of S-100 protein in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumors with particular reference to benign and malignant Schwann cell tumors. Lab. Investig. 1983, 49, 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, A.J.; Wen, D.R. S-100 protein as a marker for melanocytic and other tumours. Pathology 1985, 17, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Neuro. Oncol. 2021, 23, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Lou, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Chu, R.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Z.; Li, D.; Wan, W.; et al. Long-term postoperative outcomes of spinal cellular schwannoma: Study of 93 consecutive cases. Spine J. 2024, 24, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, J.M.; Godwin, T.A.; Erlandson, R.A.; Susin, M.; Martini, N. Cellular schwannoma: A variety of schwannoma sometimes mistaken for a malignant tumor. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1981, 5, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, K.; Mera, Y.; Uchimiya, H.; Katahira, Y.; Kanzaki, T. Plexiform schwannoma. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2003, 28, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.S.L. Epithelioid schwannoma - rare but unequivocal. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2024, 51, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindblom, L.G.; Meis-Kindblom, J.M.; Havel, G.; Busch, C. Benign epithelioid schwannoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1998, 22, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, B.A.; Welling, D.B.; Akhmametyeva, E.; Chang, L.S. The molecular biology of vestibular schwannomas: Dissecting the pathogenic process at the molecular level. Otol. Neurotol. 2006, 27, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.S.; Rizk, A.; Ebner, F.H.; van Eck, A.; Naros, G.; Horstmann, G.; Tatagiba, M. Cystic vestibular schwannoma - a subgroup analysis from a comparative study between radiosurgery and microsurgery. Neurosurg. Rev. 2024, 47, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case Ref. | Publication Date | Origin | Age (Years) | Sex | Largest Dimension (cm) | Chief Complaint | Characteristics of the Disease | Clinical Course and Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [50] | 2010 | Japan | 58 | Male | 0.3 | Recurrent episodes of right subcostal pain persisting for several years. | Schwannoma of the gallbladder associated with gallstones. | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. |

| 2 [52] | 2014 | China | 55 | Male | 2.5 | Gallbladder mass found during physical exam. | Primary gallbladder schwannoma. | Underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. No signs of recurrence observed at 12-month follow-up. |

| 3 [53] | 2016 | China | 31 | Female | 5 × 3.5 | Intermittent abdominal discomfort with mild bloating and occasional pain for the past 7 years. | Multiple schwannomas located in the porta hepatis, liver parenchyma, and gallbladder. | Underwent open surgical resection of the tumor. No recurrence or complications were observed during the 70-month follow-up period. |

| 4 [54] | 2018 | China | 70 | Male | - | Epigastric pain for 3 days with a history of jaundice. | Schwannoma of the gallbladder associated with gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones. | Underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. No recurrence detected during 19-month follow-up. |

| 5 [16] | 2020 | Japan | 40 | Female | 3.7 × 1.7 | Gallbladder mass found during physical exam. | Schwannoma of the gallbladder associated with sarcoidosis. | Underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy with no signs of recurrence at 5-month follow-up. |

| 6 [55] | 2020 | America | 67 | Female | 4.2 | Gallbladder mass found during physical exam. | Schwannoma with degenerative atypia. | Underwent cholecystectomy and gallbladder bed resection. No recurrence observed with good recovery at 2-month follow-up. |

| 7 [56] | 2023 | China | 21 | Female | 19 × 9 | 10-week gestation, experiencing epigastric pain for more than 1 month. | Schwannoma of the gallbladder coexisting with pregnancy. | Underwent open cholecystectomy with satisfactory recovery and no postoperative complications. |

| 8 [20] | 2024 | America | 12 | Female | 17 × 6 × 2 | 2-year history of biliary colic, featuring moderate-severe dull RUQ pain. | Multiple schwannomas on physical exam, with ocular findings (bilateral ERM, anisometropia, amblyopia, macular scar, eyelid laxity) meeting NF2 diagnostic criteria. | The patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Three-month postoperative surveillance revealed no recurrence of gallbladder lesions. With an established diagnosis of Neurofibromatosis Type 2 (NF2), clinical follow-up documented disease progression accompanied by exacerbation of ocular symptoms. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Q.; Huang, R.; Ni, S.; Jin, X.; Bai, X.; Wang, L.; Zhu, W. Gallbladder Schwannoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2827. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222827

Liu Q, Huang R, Ni S, Jin X, Bai X, Wang L, Zhu W. Gallbladder Schwannoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(22):2827. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222827

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Qinyu, Runze Huang, Shujuan Ni, Xin Jin, Xuanci Bai, Lu Wang, and Weiping Zhu. 2025. "Gallbladder Schwannoma: A Case Report and Literature Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 22: 2827. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222827

APA StyleLiu, Q., Huang, R., Ni, S., Jin, X., Bai, X., Wang, L., & Zhu, W. (2025). Gallbladder Schwannoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics, 15(22), 2827. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15222827