Are Scoring Systems Useful in Predicting Mortality from Upper GI Bleeding in Geriatric Patients?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. Study Protocol

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Patient Grouping

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomopoulos, K.C.; Vagenas, K.A.; Vagianos, C.E.; Margaritis, V.G.; Blikas, A.P.; Katsakoulis, E.C.; Nikolopoulou, V.N. Changes in aetiology and clinical outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding during the last 15 years. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2004, 16, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.S.; Bargujar, P.; Pahadiya, H.R.; Yadav, R.K.; Upadhyay, J.; Gupta, A.; Lakhotia, M. Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Hexagenerians or Older (≥60 Years) Versus Younger (<60 Years) Patients: Clinico-Endoscopic Profile and Outcome. Cureus 2021, 13, e13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torn, M.; Bollen, W.L.; van der Meer, F.J.; van der Wall, E.E.; Rosendaal, F.R. Risks of oral anticoagulant therapy with increasing age. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 1527–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez -Cara, J.G.; Jiménez-Rosales, R.; Úbeda-Muñoz, M.; de Hierro, M.L.; de Teresa, J.; Redondo-Cerezo, E. Comparison of AIMS65, Glasgow-Blatchford score, and Rockall score in Europe series of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Performance when predicting in-hospital and delayed Mortality. UEG J. 2016, 4, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpen-Palmer, J.; Stanley, A.J. Update on the management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ Med. 2022, 1, e000202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.Y.W.; Yu, Y.; Tang, R.S.Y.; Chan, H.C.H.; Yip, H.C.; Chan, S.M.; Luk, S.W.Y.; Wong, S.H.; Lau, L.H.S.; Lui, R.N.; et al. Timing of Endoscopy for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, H.H.; Wu, P.Y.; Wu, T.L.; Huang, S.P.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, M.F.; Lin, W.C.; Tsai, C.L.; Lin, K.P. Forrest Classification for Bleeding Peptic Ulcer: A New Look at the Old Endoscopic Classification. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, M.A.; Peker, K.D.; Unsal, M.G.; Yırgın, H.; Kahraman, İ.; Alış, H. The Importance of Rockall Scoring System for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Long Term Follow-Up. Indian J. Surg. 2017, 79, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curdia Gonçalves, T.; Barbosa, M.; Xavier, S.; Boal Carvalho, P.; Magalhães, J.; Marinho, C.; Cotter, J. AIMS65 score: A new prognostic tool to predict mortality in variceal bleeding. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 469–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Yeum, S.C.; Kim, B.W.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Sim, E.H.; Ji, J.S.; Choi, H. Comparison of AIMS65 Score and Other Scoring Systems for Predicting Clinical Outcomes in Koreans with Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gut Liver 2016, 10, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.C.; Jang, S.; Martins, B.D.C.; Stevens, T.; Jairath, V.; Lopez, R.; Vargo, J.J.; Barkun, A.; Maluf-Filho, F. Risk Stratification in Cancer Patients with Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Comparison of Glasgow-Blatchford, Rockall and AIMS65, and Development of a New Scoring System. Clin. Endosc. 2022, 55, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagir, Y.; Durak, M.B.; Yuksel, I. Optimal endoscopy timing in elderly patients presenting with acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024, 24, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.M.; Jeon, S.W.; Jung, J.T.; Lee, D.W.; Ha, C.Y.; Park, K.S.; Lee, S.H.; Yang, C.H.; Park, J.H.; Park, Y.S. Daegu-Gyeongbuk Gastrointestinal Study Group (DGSG). Comparison of scoring systems for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A multicenter prospective cohort study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 31, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Z.; Che, H.; Xie, D.; Ren, J.; Si, Q. Prediction of 30-day in-hospital mortality in older UGIB patients using a simplified risk score and comparison with AIMS65 score. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H. Comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems for the prediction of the risk of in-hospital death among patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Rev. Esp. Enferm. Dig. 2020, 112, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, K.B.; Moon, H.S.; In, K.R.; Kang, S.H.; Sung, J.K.; Jeong, H.Y. Which scoring systems are useful for predicting the prognosis of lower gastrointestinal bleeding? Old and new. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, P.; Iordache, S.; Florescu, D.N.; Iovanescu, V.F.; Vieru, A.; Barbu, V.; Bezna, M.C.; Alexandru, D.O.; Ungureanu, B.S.; Cazacu, S.M. Mortality Rate in Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding Associated with Anti-Thrombotic Therapy Before and During COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 2679–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shung, D.; Tsay, C.; Laine, L.; Chang, D.; Li, F.; Thomas, P.; Partridge, C.; Simonov, M.; Hsiao, A.; Tay, J.K.; et al. Early identification of patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding using natural language processing and decision rules. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, B.S.; Han, K.D.; Park, J.B.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.P.; Kim, Y.J. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on oral anticoagulant and proton pump inhibitor co-therapy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kılıç, M.; Ak, R.; Dalkılınç Hökenek, U.; Alışkan, H. Use of the AIMS65 and pre-endoscopy Rockall scores in the prediction of mortality in patients with the upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ulus. Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022, 29, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Moon, H.S.; Kwon, I.S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kang, S.H.; Sung, J.K.; Lee, E.S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, B.S.; et al. Validation of a new risk score system for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020, 20, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, H.; Abreu, E.; Cheng, A.L. Serum Albumin Trend Is a Predictor of Mortality in ICU Patients with Sepsis. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2019, 21, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viazis, N.; Christodoulou, D.; Papastergiou, V.; Mousourakis, K.; Kozompoli, D.; Stasinos, G.; Dimopoulou, K.; Apostolopoulos, P.; Fousekis, F.; Liatsos, C.; et al. Diagnostic Yield and Outcomes of Small Bowel Capsule Endoscopy in Patients with Small Bowel Bleeding Receiving Antithrombotics. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyett, B.H.; Abougergi, M.S.; Charpentier, J.P.; Kumar, N.L.; Brozovic, S.; Claggett, B.L.; Travis, A.C.; Saltzman, J.R. The AIMS65 score compared with the glasgow-blatchford score in prediction outcomes in upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2013, 77, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçmak, F.; Tuncel, E.T. Effectiveness of Pre-Endoscopy Risk Scores in Predicting Clinical Course in Patients with Non-Varicose Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Dicle Med. J. 2024, 51, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.; Majumdar, A.; Boyapati, R.; Chung, W.; Worland, T.; Terbah, R.; Wei, J.; Lontos, S.; Angus, P.; Vaughan, R. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: Comparison of the AIMS65 score with the glasgow-blatchford and rockall Scoring systems. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2016, 83, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.; Ouejiaraphant, C.; Akarapatima, K.; Rattanasupa, A.; Prachayakul, V. Prospective comparison of the AIMS65 score, glasgow-blatchford score, and rockall scores for predicting clinical Outcomes in patients with variceal and nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin. Endosc. 2021, 54, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.S.; Choi, J.; Shin, W.C. AIMS65 scoring system is comparable to Glasgow- Blatchford scores or Rockall scores for clinical prediction outcomes for non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 19, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.H.; Oh, J.H.; Lee, H.Y.; Jeong, J.W.; Go, S.E.; You, C.R.; Jeon, E.J.; Choi, S.W. Is the AIMS65 score useful in predicting outcomes in peptic ulcer bleeding ? World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 1846–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, C.; Zhang, J.; Lian, J.; Utsav, J.; Iyer, C.; Low, S.; Saeed, H.; Zahid, S.; Okolo, P.I., 3rd. Anatomical location, risk factors, and outcomes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding in colorectal cancer patients: A national inpatient sample analysis (2009–2019). Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2023, 38, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age (Years) | 77.6 ± 8.7 (60–86) | |

| Gender (n/%) | F/M 32 (50%)/32 (50%) | |

| Comorbid diseases | HT | 42 (65.6%) |

| DM | 35 (54.7%) | |

| HF | 26 (40.6%) | |

| CKD | 15 (23.4%) | |

| Malignancy | 11 (17.2) | |

| Neurological diseases | 9 (14.1) | |

| Chronic lung diseases | 4 (6.2%) | |

| Chronic liver disease | 7 (10.9) | |

| Drug Use | None | n: 27 (42.2%) |

| Anticoagulants or DOACs | n: 25 (39.1%) | |

| NSAIDs | n: 12 (18.7%) | |

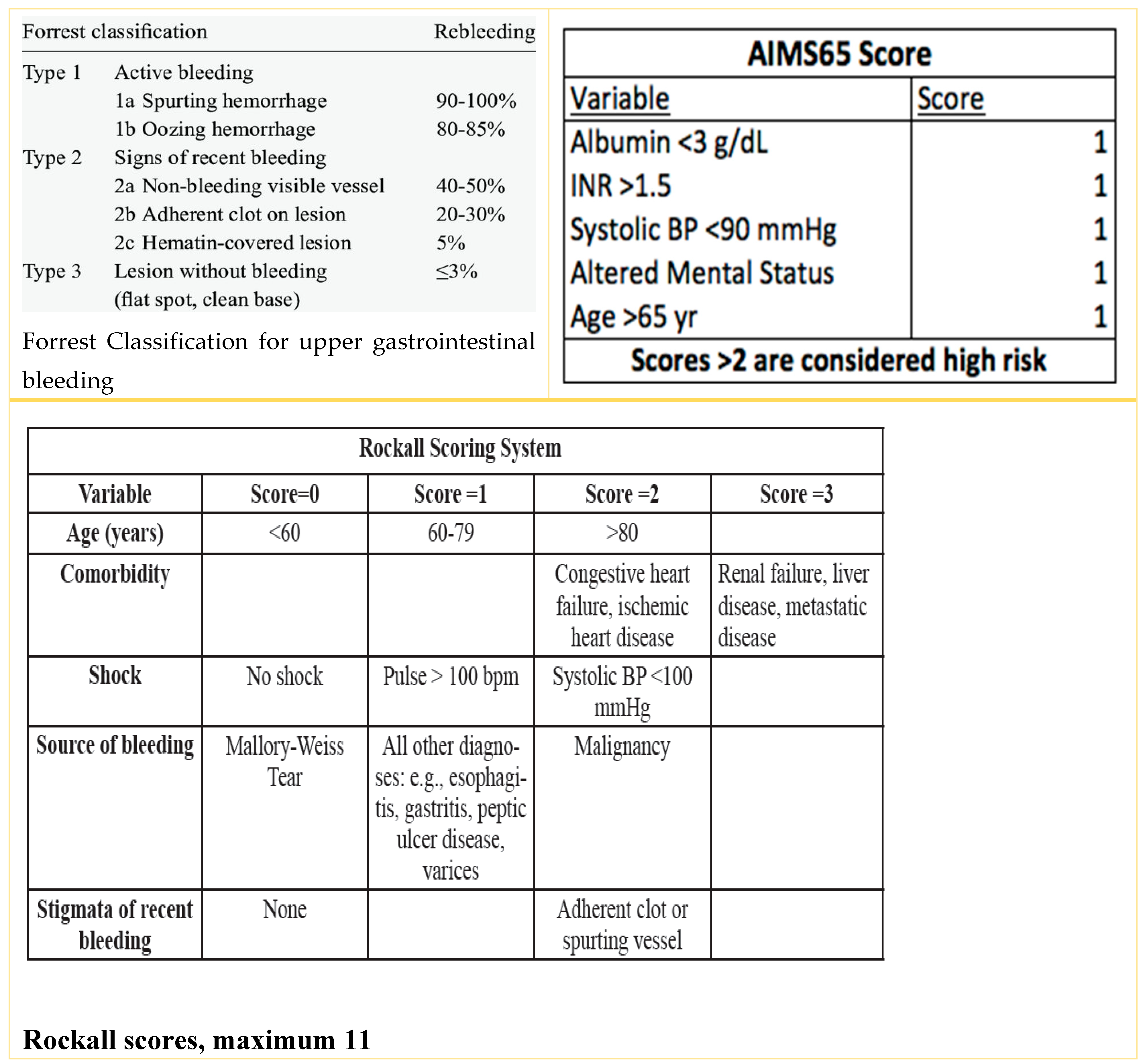

| Forrest classification | Forrest 3: 54.7% | |

| Forrest 2c: 9.3% | ||

| Forrest 2b: 21.8% | ||

| Forrest 2a: 6.2% | ||

| Forrest 1b: 6.2% | ||

| Forrest 1a: 1.5% | ||

| Causes of death | Sepsis: 7.8% | |

| Decompensated heart failure and cardiac disease: 4.7% | ||

| Malignant disease: 4.7% | ||

| Chronic renal failure: 1.5% | ||

| Recovered (n = 52) | Death (n = 12) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

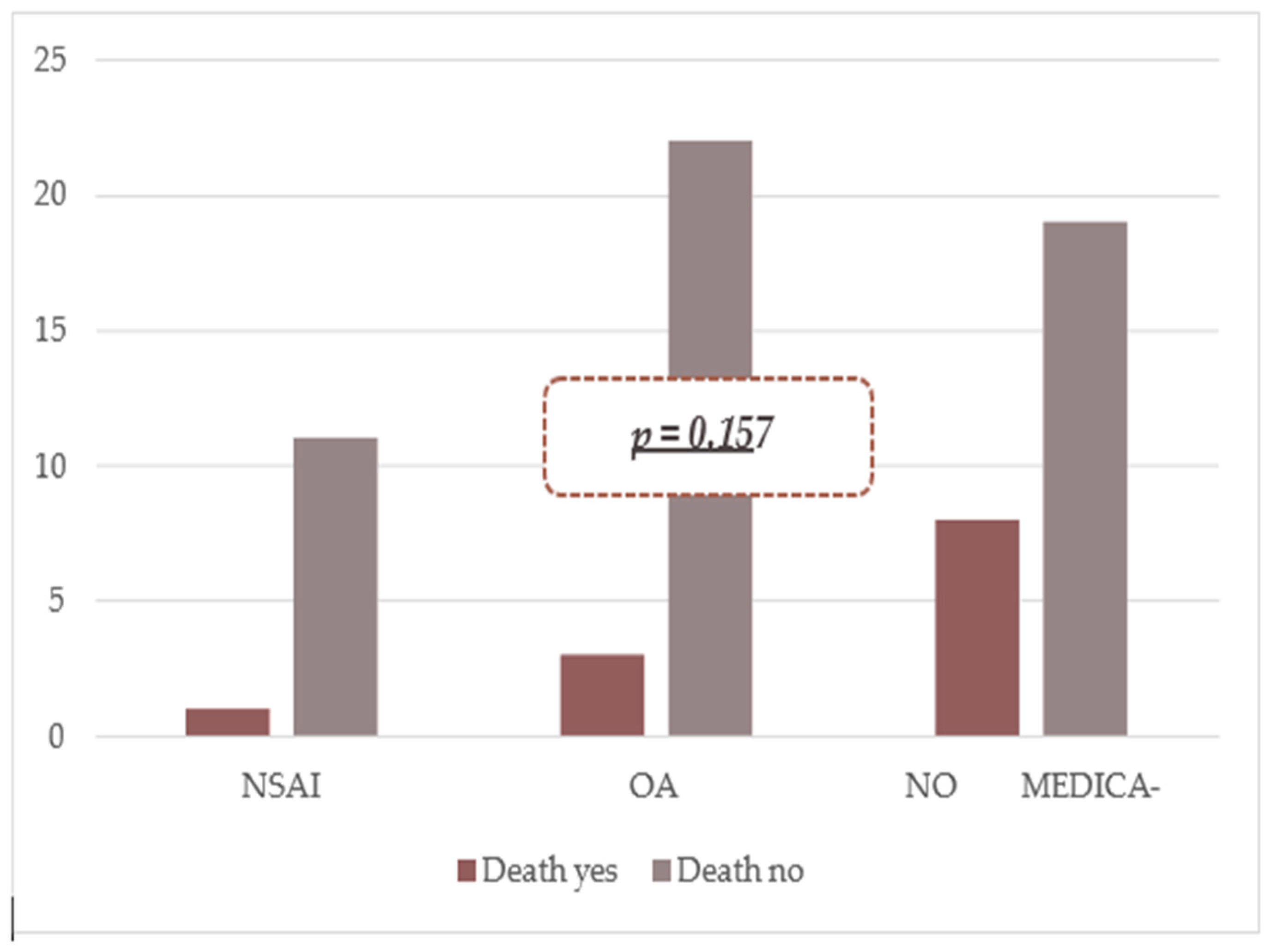

| NSAID | 11 (91.7%) | 1 (8.3%) | 0.324 | 0.33 (0.3–2.9) |

| OAC | 22 (88.0%) | 3 (12.0%) | 0.275 | 0.45 (0.1–1.8) |

| Does Not Use Medication | 19 (70.4%) | 8 (29.6%) | 0.065 | 3.47 (0.9–13.0) |

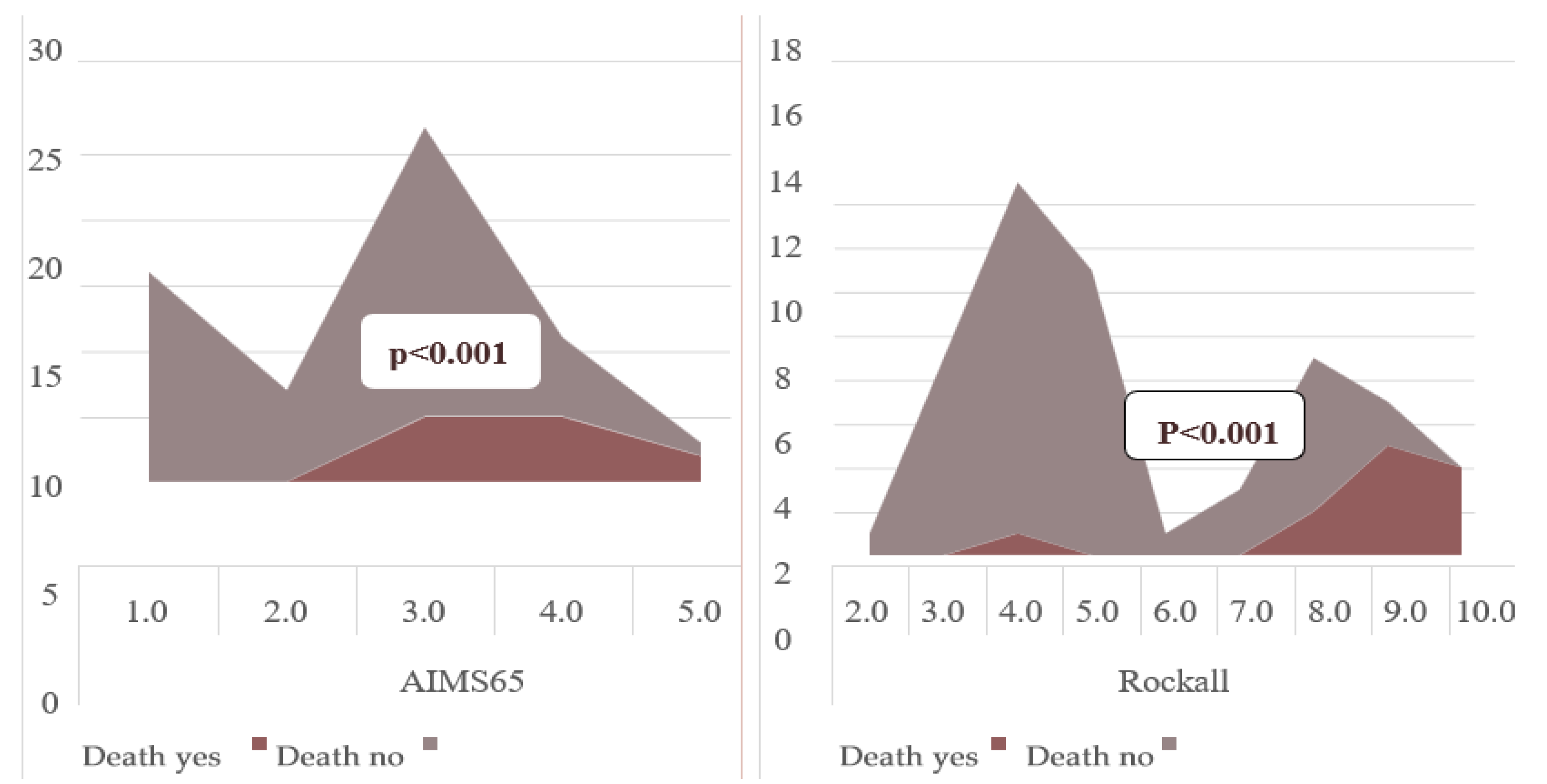

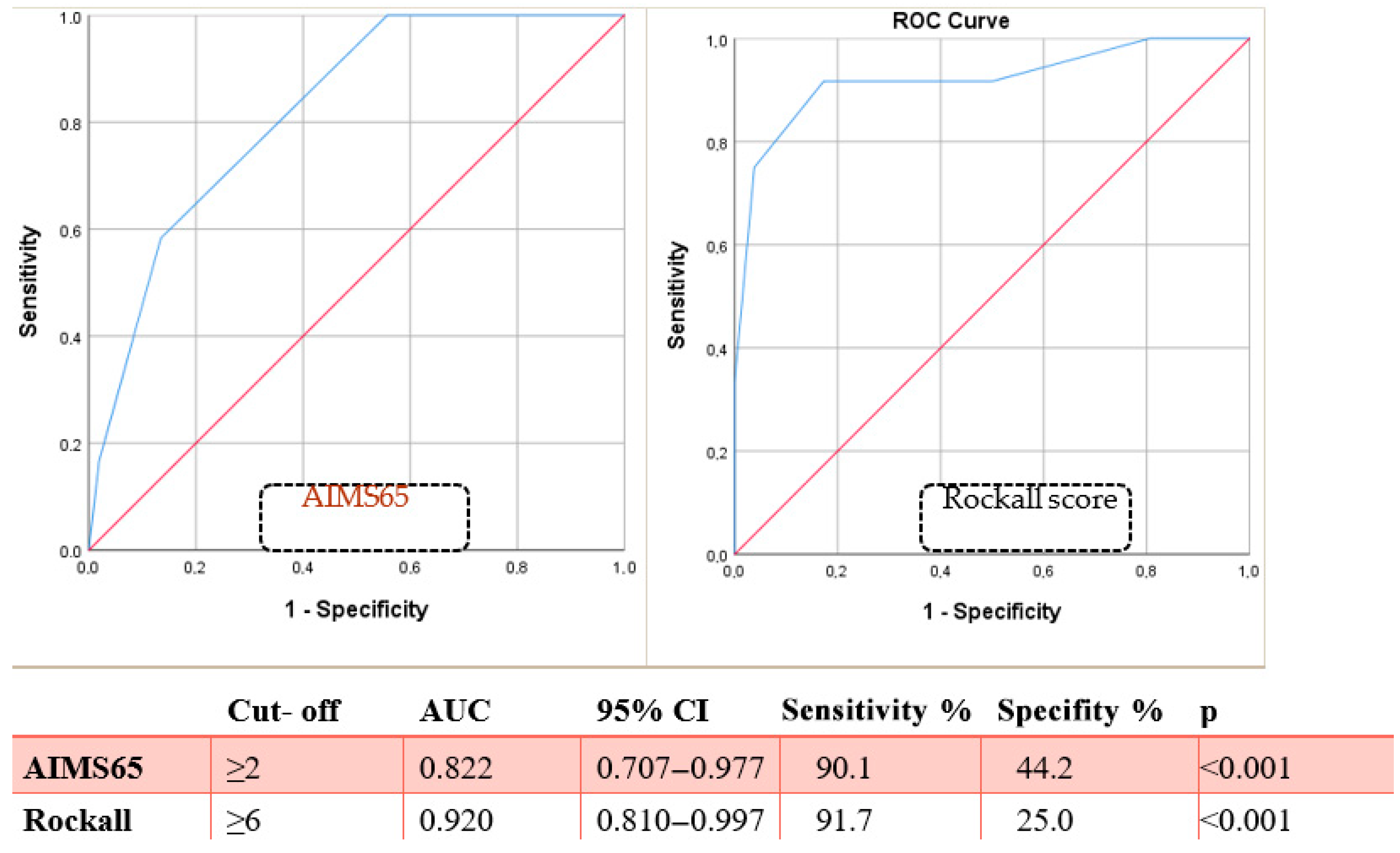

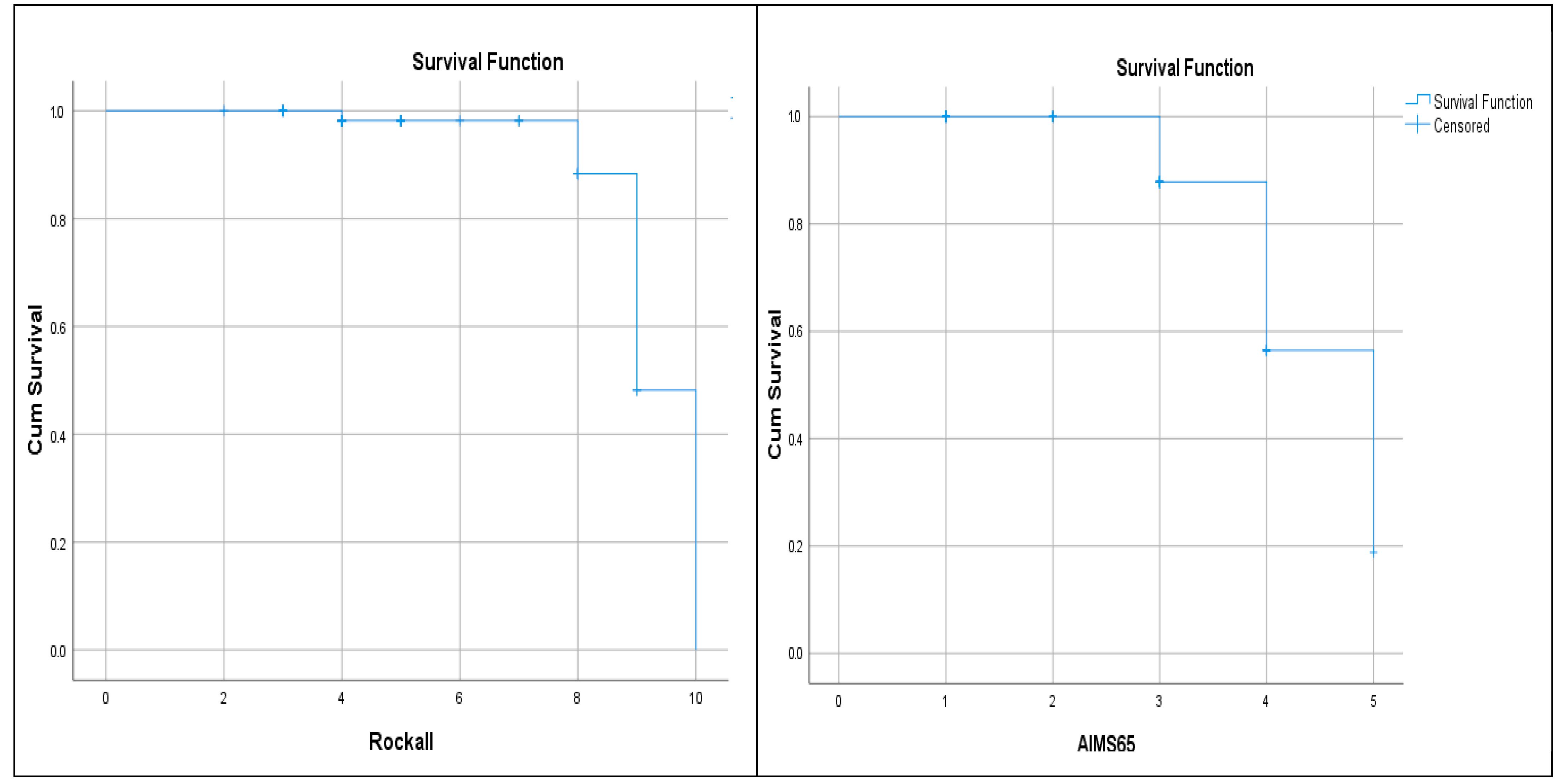

| AIMS65 (mean) | 2.40 ± 1.10 | 3.75 ± 0.75 | <0.001 | |

| AIMS65 (≥2) | 13 (25.0%) | 11 (91.6%) | 0.001 | 33.0 (3.8–136.5) |

| Rockall (mean) | 4.98 ± 1.82 | 8.75 ± 1.65 | <0.001 | |

| Rockall (≥6) | 14 (26.9%) | 10 (83.3%) | 0.001 | 13.5 (2.6–49.7) |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| HT | 0.44 | 0.32–1.59 | 0.212 | |||

| DM | 0.79 | 0.33–2.78 | 0.717 | |||

| Sepsis | 10.25 | 2.94–25.13 | 0.004 | 6.46 | 1.50–10.89 | 0.009 |

| Heart failure | 5.00 | 2.26–11.69 | 0.011 | 3.18 | 1.24–7.63 | 0.026 |

| Chronic liver disease | 0.69 | 0.09–6.40 | 0.749 | |||

| Chronic kidney disease | 3.83 | 0.98–10.58 | 0.023 | 1.99 | 0.99–5.01 | 0.051 |

| Chronic lung disease | 0.53 | 0.27–9.63 | 0.683 | |||

| Malignancy | 4.64 | 1.23–12.49 | 0.017 | 2.77 | 1.17–6.85 | 0.040 |

| Neurological diseases | 0.51 | 0.05–4.32 | 0.546 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akkuzu, M.Z.; Ebik, B. Are Scoring Systems Useful in Predicting Mortality from Upper GI Bleeding in Geriatric Patients? Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2173. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172173

Akkuzu MZ, Ebik B. Are Scoring Systems Useful in Predicting Mortality from Upper GI Bleeding in Geriatric Patients? Diagnostics. 2025; 15(17):2173. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172173

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkkuzu, Mustafa Zanyar, and Berat Ebik. 2025. "Are Scoring Systems Useful in Predicting Mortality from Upper GI Bleeding in Geriatric Patients?" Diagnostics 15, no. 17: 2173. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172173

APA StyleAkkuzu, M. Z., & Ebik, B. (2025). Are Scoring Systems Useful in Predicting Mortality from Upper GI Bleeding in Geriatric Patients? Diagnostics, 15(17), 2173. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172173