From Benign Polyp to High-Grade Endometrial Sarcoma: A Case Report with Imaging Correlation

Abstract

1. Background

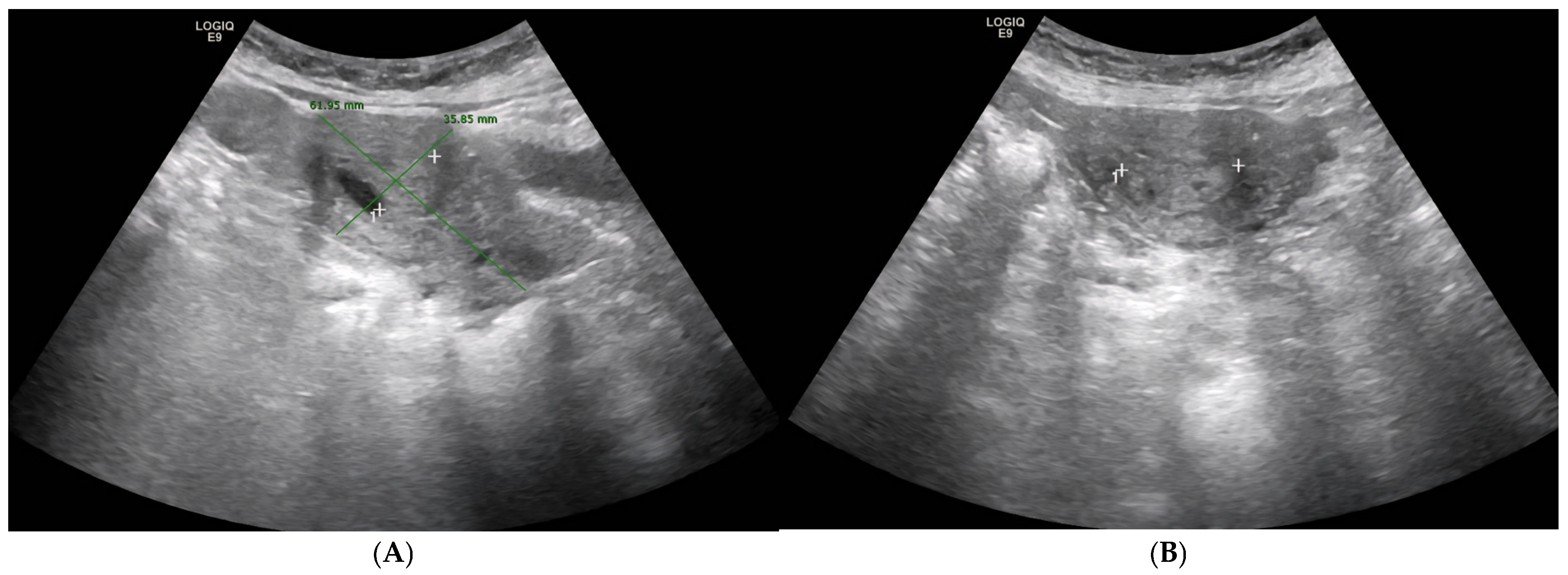

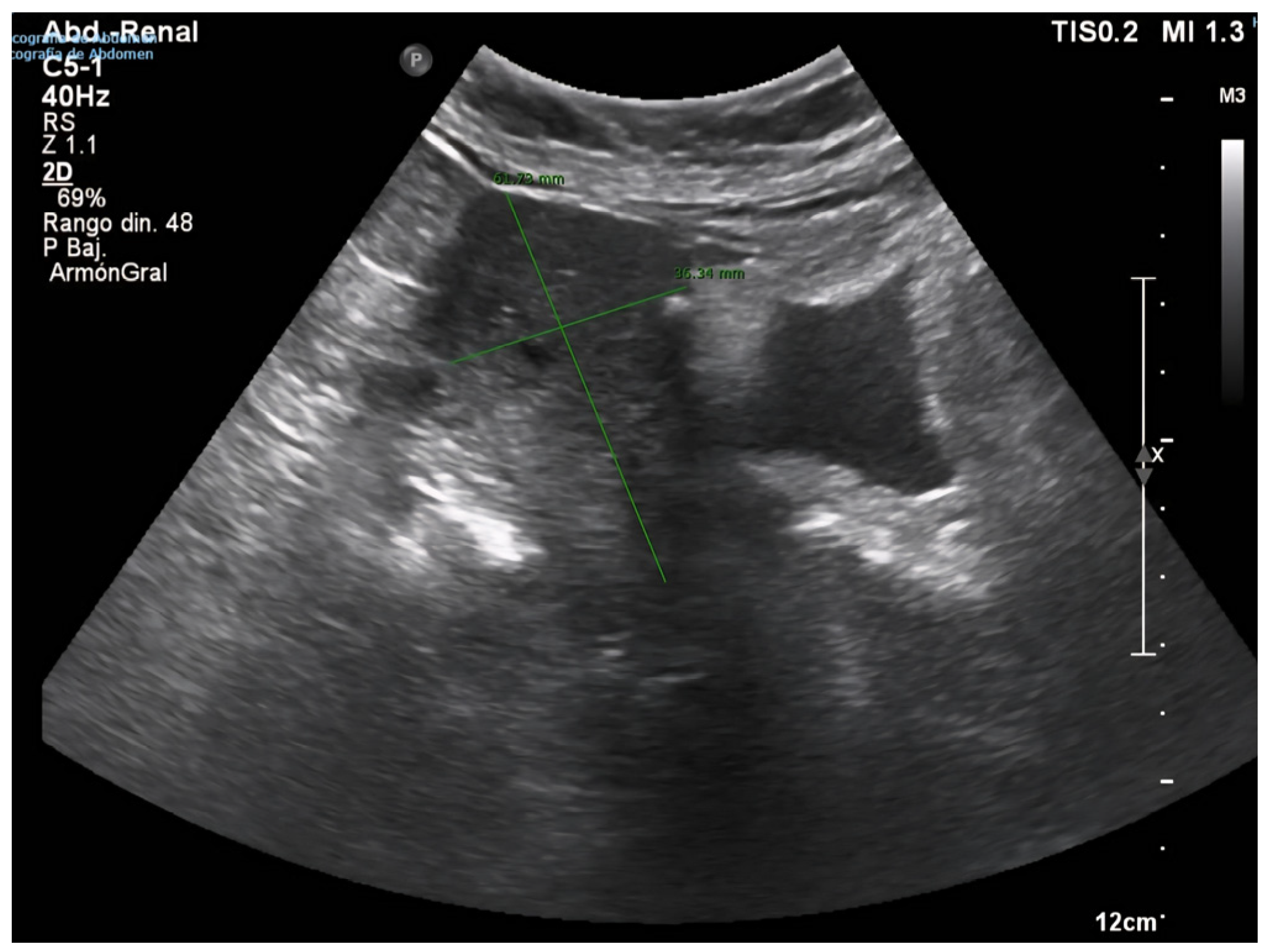

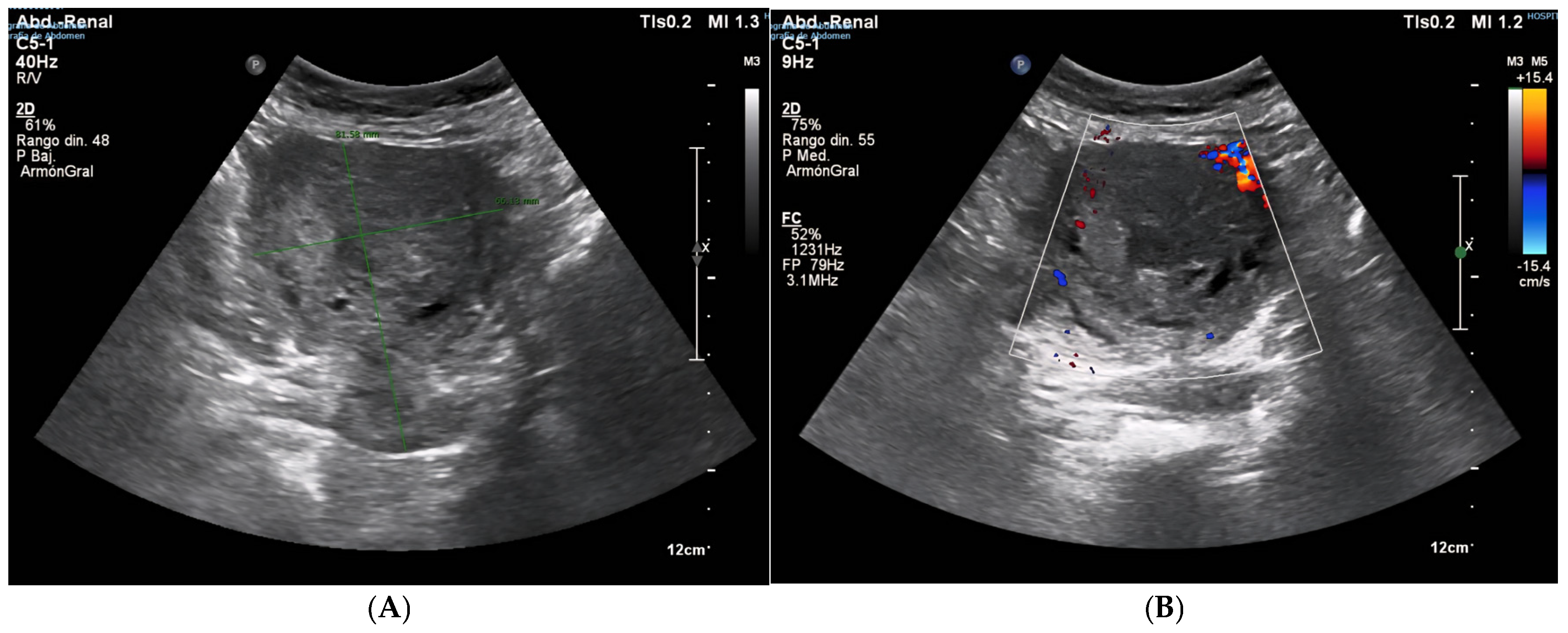

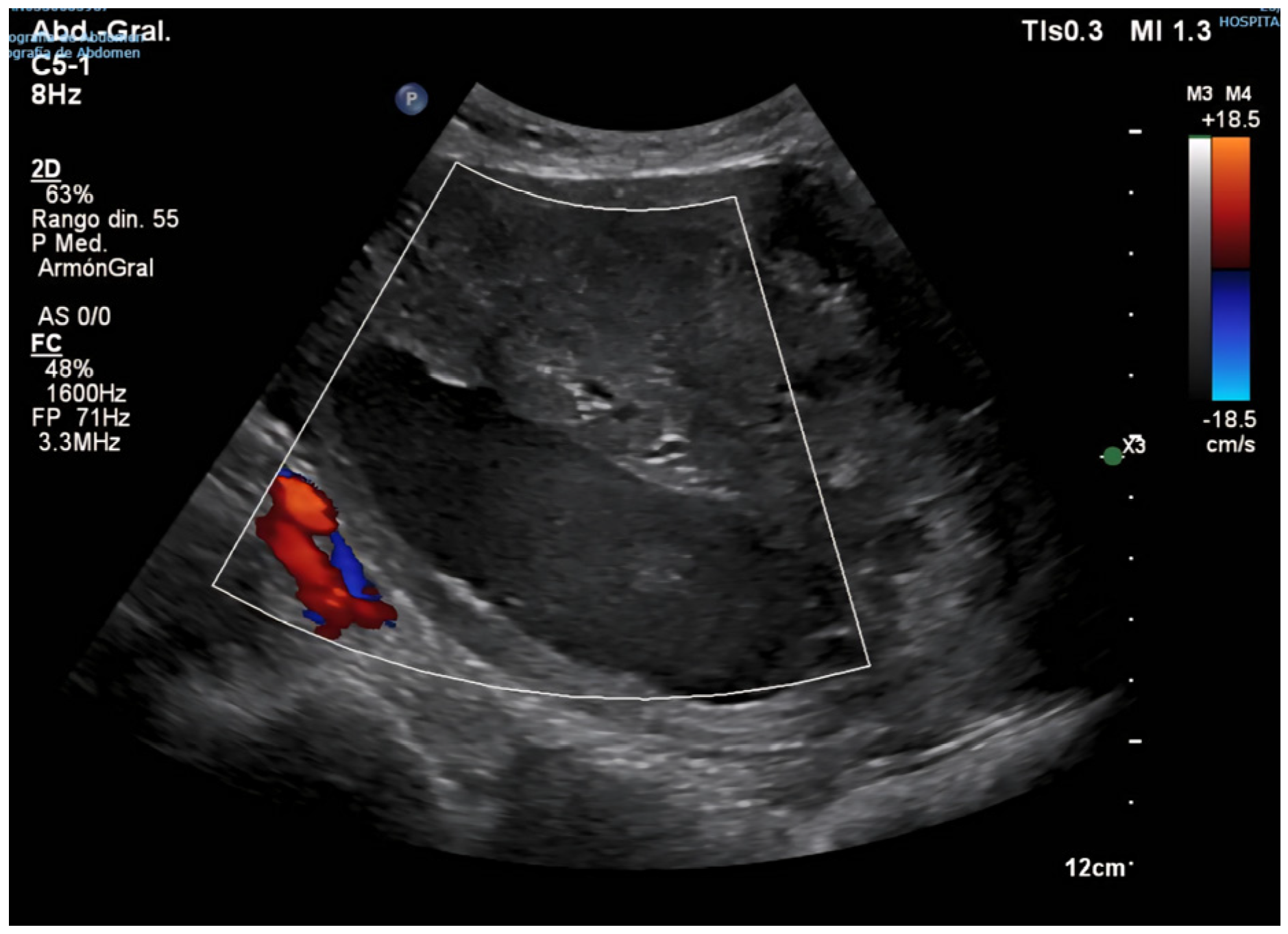

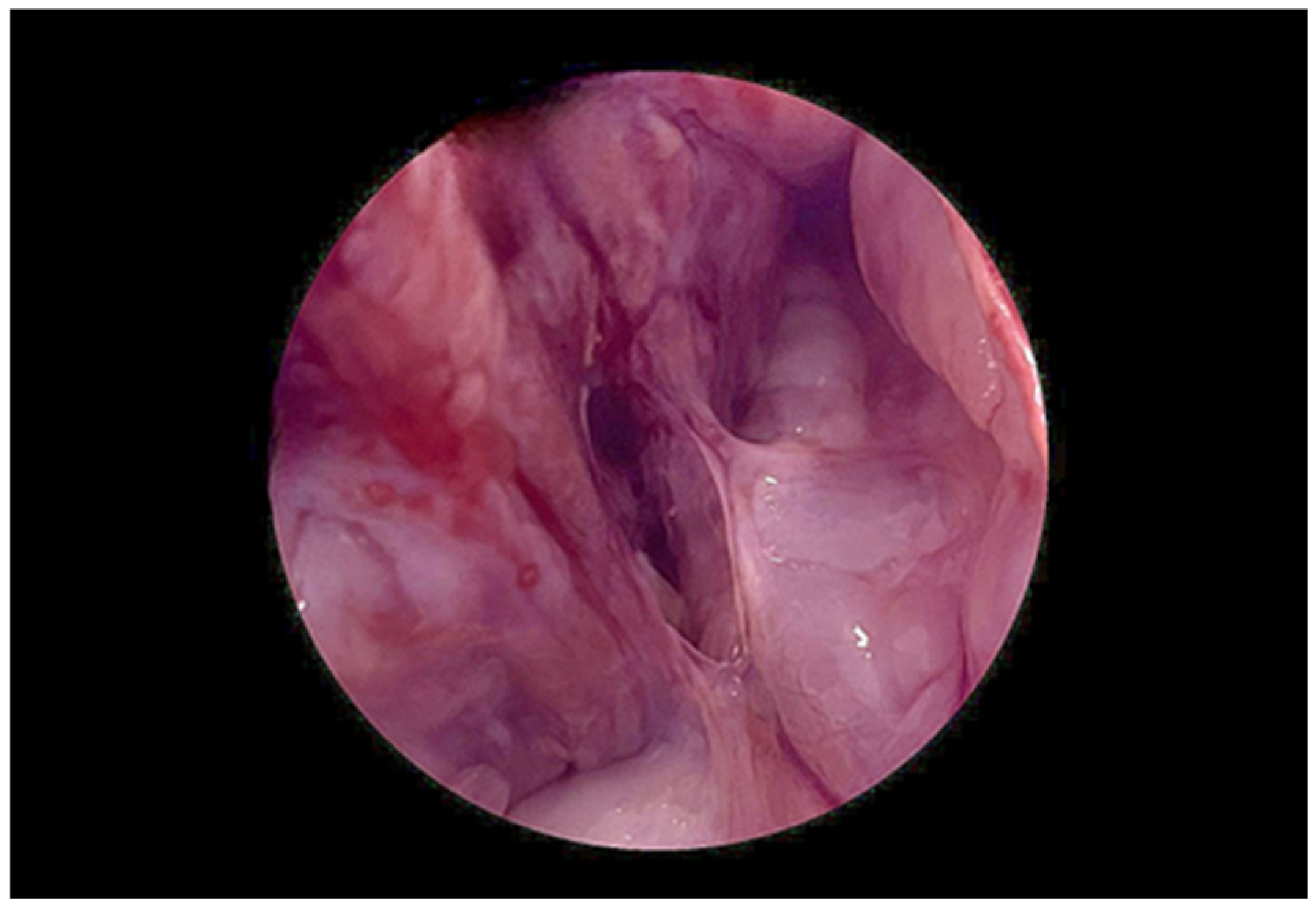

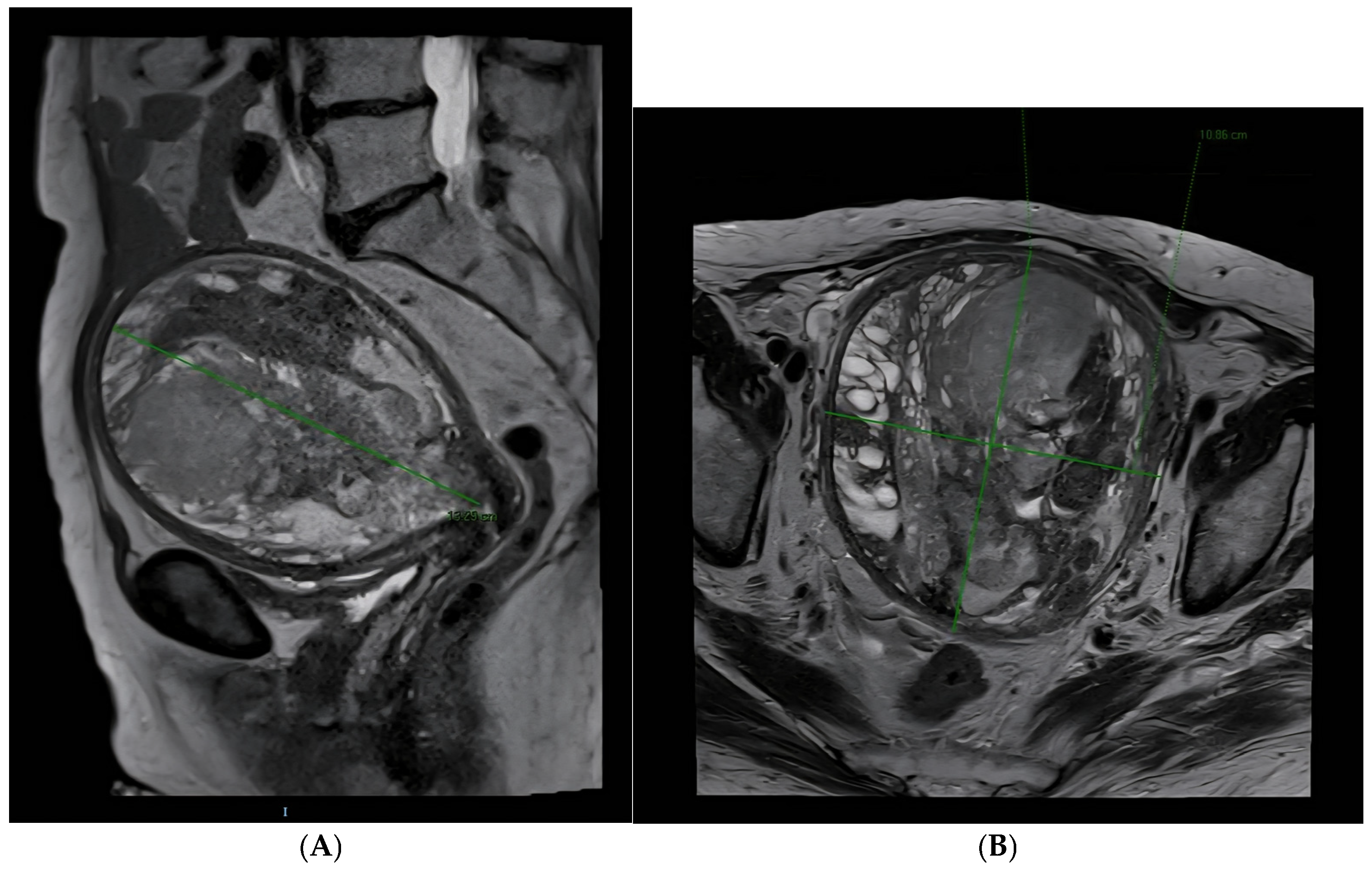

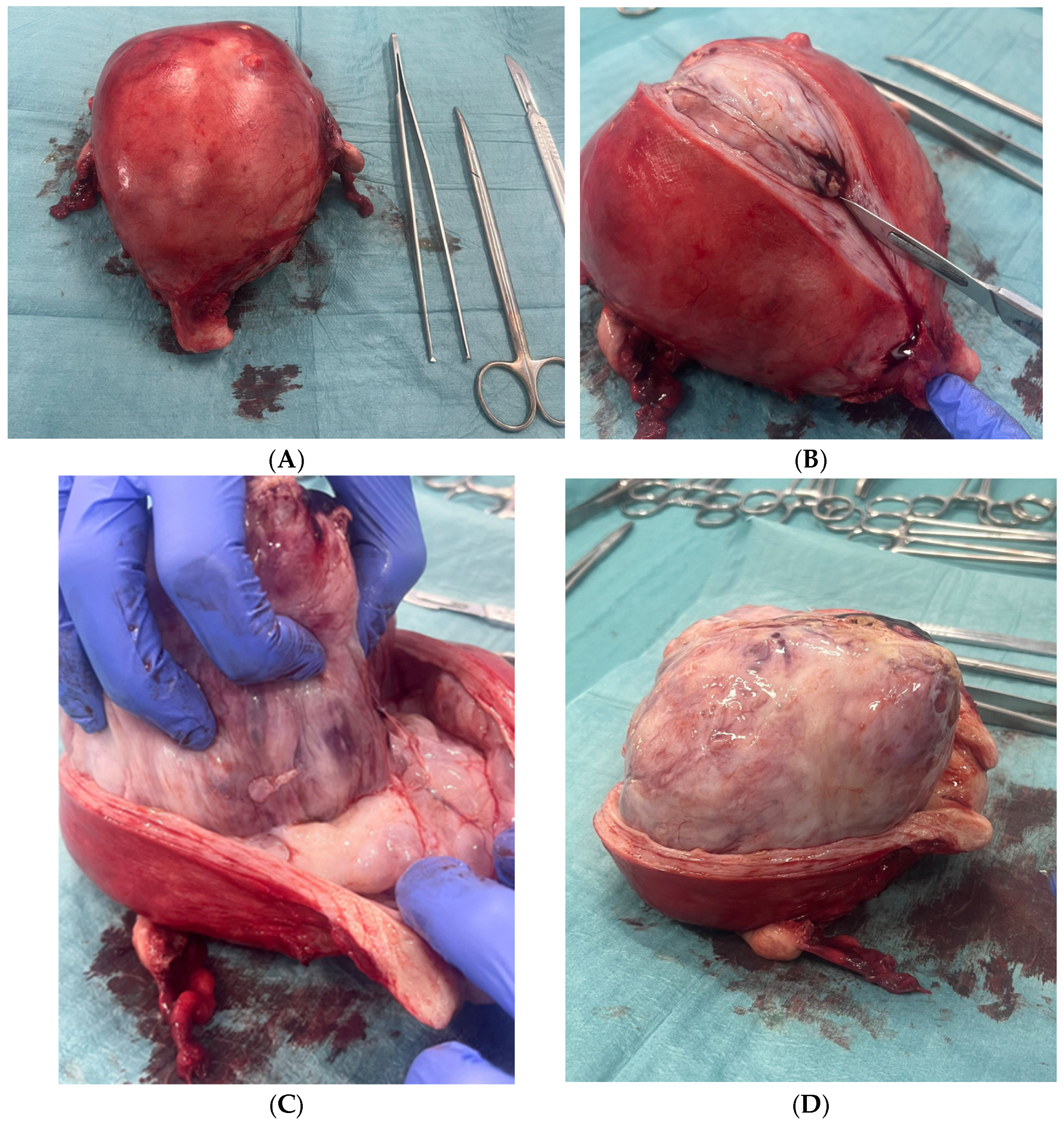

2. Case Presentation

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ray-Coquard, I.; Casali, P.G.; Croce, S.; Fennessy, F.M.; Fischerova, D.; Jones, R.; Sanfilippo, R.; Zapardiel, I.; Amant, F.; Blay, J.Y.; et al. ESGO/ESMO/EURACAN/GCIG Uterine Sarcoma Guidelines. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2025, 35, S1–S35. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Rustum, N.; Yashar, C.; Arend, R.; Barber, E.; Bradley, K.; Brooks, R.; Campos, S.M.; Chino, J.; Chon, H.S.; Chu, C.; et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Uterine Neoplasms. Version 1. 2023. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2025, 21, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN. Patient Guidelines for Uterine Cancer. Online Resource. 2023. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/patientresources/patient-resources/guidelines-for-patients/guidelines-for-patients-details?patientGuidelineId=41 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Morikawa, K.; Baba, A.; Matsushima, S.; Ohki, Y.; Shiraishi, M.; Kawabata, A.; Ukai, N.; Ojiri, H. Magnetic resonance imaging features of uterine adenosarcoma: Case series and systematic review. Abdom. Radiol. 2025, 50, 3313–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, K.; Kurata, Y.; Himoto, Y.; Kido, A.; Kirita, M.; Yoshida, A.; Matsumoto, Y.K.; Hamanishi, J.; Minamiguchi, S.; Ito, H.; et al. Differentiating uterine adenosarcoma from endometrial polyps: MRI imaging features. Abdom. Radiol. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fidalgo, J.A.; Ortega, E.; Ponce, J.; Redondo, A.; Sevilla, I.; Valverde, C.; Verdum, J.I.; de Alava, E.; López, M.G.; Marquina, G.; et al. Uterine sarcomas: GEIS Guidelines. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2023, 15, 17588359231157645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Solearo, E.; Orcioni, G.F.; Garaventa, L.; Uccella, S.; Puppo, A. Uterine adenosarcoma: An unpredictable enemy. J. Clin. Med. Surg. 2023, 3, 1075. [Google Scholar]

- Mbatani, N.; Olawaiye, A.B.; Prat, J. Uterine sarcomas. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 143 (Suppl. 2), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathenson, M.J.; Conley, A.P. Prognostic factors for uterine adenosarcoma: A review. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2018, 18, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, U.A.; Denschlag, D. Uterine adenosarcoma. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2018, 41, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Mutlu, L.; Tymon-Rosario, J.; Khadraoui, W.; Nagarkatti, N.; Hui, P.; Buza, N.; Lu, L.; Schwartz, P.; Menderes, G. Clinicopathologic characteristics and oncologic outcomes in adenosarcoma of gynecologic sites. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 39, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecalco-Cruz, A.C.; Cortés-González, C.C. Adenosarcoma uterino con sobrecrecimiento sarcomatoso: Un raro y agresivo cáncer para las mujeres después de la menopausia. Gac. Mex. Oncol. 2021, 20, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, A.; Amemiya, Y.; Seth, A.; Djordjevic, B.; Parra-Herran, C. High-grade Mullerian adenosarcoma: Genomic and clinicopathologic characterization. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 41, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, E.J.; Toussaint, T.; Leitao, M.M., Jr.; Hensley, M.L.; Soslow, R.A.; Gardner, G.J.; Jewell, E.L. Management of uterine adenosarcomas with and without sarcomatous overgrowth. Gynecol. Oncol. 2013, 129, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Ramirez, P.T.; Westin, S.N.; Soliman, P.T.; Munsell, M.F.; Nick, A.M.; Schmeler, K.M.; Klopp, A.H.; Fleming, N.D. Uterine adenosarcoma: Management, outcomes and risk factors for recurrence. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 135, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, M.L.; Covens, A.; Glasspool, R.M.; Hilpert, F.; Kristensen, G.; Kwon, S.; Selleet, F.; Small, W.; Witteveen, E.; Russell, P. GCIG consensus for Müllerian adenosarcoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2014, 24 (Suppl. 3), S78–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.; Cunha, T.M. Uterine sarcomas: Clinical presentation and MRI features. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2015, 21, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, G.; Matsutani, H.; Yamada, T.; Ohmichi, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Osuga, K. Imaging findings of uterine adenosarcoma with sarcomatous overgrowth: Two case reports emphasizing restricted diffusion. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia. Oncoguía SEGO: Sarcoma uterino 2023. In Oncoguías de Práctica Clínica en Cáncer Ginecológico y Mamario; SEGO: Madrid, Spain, 2022; ISBN 978-84-09-40085-0. Online resource; Available online: https://oncosego.sego.es/oncoguia-sarcoma-uterino-2023-b (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Grupo Español de Investigación en Sarcomas (GEIS). Guía Práctica Clínica de Sarcomas de Útero (Incluye Adenosarcoma) [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://flasog.org/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Yoshizako, T.; Wada, A.; Kitagaki, H.; Ishikawa, N.; Miyazaki, K. MR imaging of uterine adenosarcoma: Case report and literature review. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 2011, 10, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, E.; Prat, J. Uterine sarcomas: A review. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 116, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, J. FIGO staging for uterine sarcomas. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2009, 104, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindman, N.; Kang, S.; Fournier, L.; Lakhman, Y.; Nougaret, S.; Reinhold, C.; Sadowski, E.; Huang, J.Q.; Ascher, S. MRI evaluation of uterine masses for risk of leiomyosarcoma: A consensus statement. Radiology 2022, 306, e211658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bean, G.R.; Anderson, J.; Sangoi, A.R.; Krings, G.; Garg, K. DICER1 mutations are frequent in müllerian adenosarcomas and are independent of rhabdomyosarcomatous differentiation. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, M.C.; Nannini, M.; Rizzo, A.; Pantaleo, M.A. Current status on treatment of uterine adenosarcoma: Updated literature review. Gynecol. Pelvic Med. 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barral, M.; Placé, V.; Dautry, R.; Bendavid, S.; Cornelis, F.; Foucher, R.; Guerrache, Y.; Soyer, P. Magnetic resonance imaging features of uterine sarcoma and mimickers. Abdom. Radiol. 2017, 42, 1762–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, D.; Horn, L.C.; Hiller, G.G.R.; Höhn, A.K.; Schmoeckel, E. Endometriale und weitere seltene uter-ine Sarkome: Diagnostische Aspekte im Kontext der WHO-Klassifikation 2020 [Endometrial and other rare uterine sarcomas: Diagnostic aspects in the context of the 2020 WHO classification]. Pathologe 2022, 43, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivak, T.C.; Seidman, J.D.; McBroom, J.W.; MacKoul, P.J.; Aye, L.M.; Rose, G.S. Uterine adenosarcoma with sarcomatous overgrowth versus carcinosarcoma: Comparison of treatment and survival. Gynecol. Oncol. 2001, 83, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaknin, A.; Bosse, T.J.; Creutzberg, C.L.; Giornelli, G.; Harter, P.; Joly, F.; Lorusso, D.; Marth, C.; Makker, V.; Mirza, M.R.; et al. ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines: Endometrial cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camponovo, C.; Neumann, S.; Zosso, L.; Mueller, M.D.; Raio, L. Sonographic and Magnetic Resonance Characteristics of Gynecological Sarcoma. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Miguel Blanc, M.; González, C.E.; Montes, M.G.; Bejarano, C.S. From Benign Polyp to High-Grade Endometrial Sarcoma: A Case Report with Imaging Correlation. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172164

de Miguel Blanc M, González CE, Montes MG, Bejarano CS. From Benign Polyp to High-Grade Endometrial Sarcoma: A Case Report with Imaging Correlation. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(17):2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172164

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Miguel Blanc, Marina, Cristina Espada González, Milagros Gálvez Montes, and Carmen Simón Bejarano. 2025. "From Benign Polyp to High-Grade Endometrial Sarcoma: A Case Report with Imaging Correlation" Diagnostics 15, no. 17: 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172164

APA Stylede Miguel Blanc, M., González, C. E., Montes, M. G., & Bejarano, C. S. (2025). From Benign Polyp to High-Grade Endometrial Sarcoma: A Case Report with Imaging Correlation. Diagnostics, 15(17), 2164. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15172164