Amelanotic Melanocytic Nevus of the Oral Cavity: A Case Report and Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

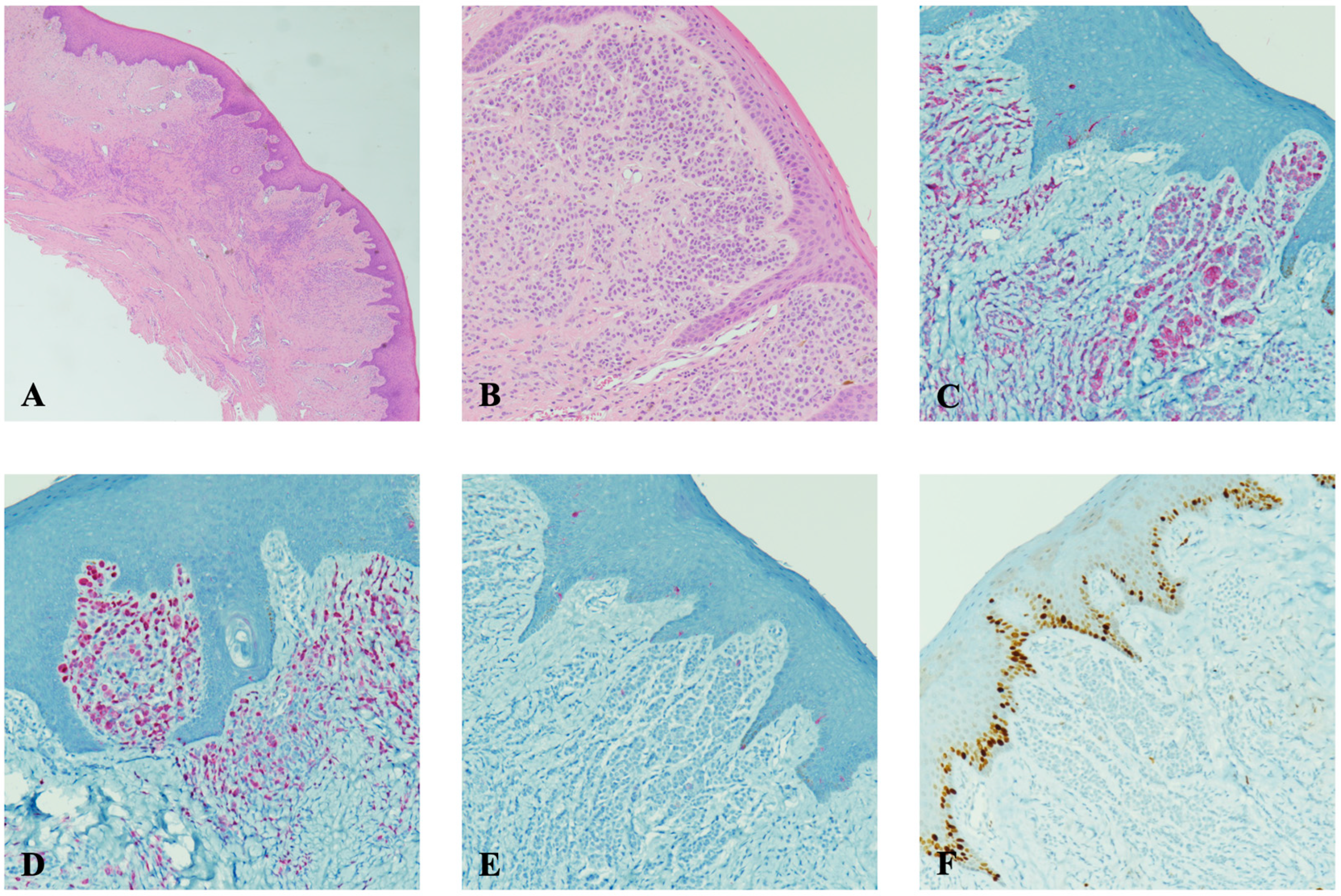

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

3.1. Verruciform Xanthoma

3.2. Peripheral Ameloblastoma

3.3. Linear Epidermal Nevus

3.4. Squamous Papilloma

3.5. Amelanotic Melanocytic Nevus

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amérigo-Góngora, M.; Machuca-Portillo, G.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Lesclous, P.; Amérigo-Navarro, J.; González-Cámpora, R. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of oral melanocytic nevi and review of the literature. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 118, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meleti, M.; Vescovi, P.; Mooi, W.J.; Van der Waal, I. Pigmented lesions of the oral mucosa and perioral tissues: A flow-chart for the diagnosis and some recommendations for the management. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2008, 105, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, A.; Hansen, L.S. Pigmented nevi of the oral mucosa: A clinicopathologic study of 36 new cases and review of 155 cases from the literature. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1987, 63, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.; Jham, B.; Assi, R.; Readinger, A.; Kessler, H.P. Oral melanocytic nevi: A clinicopathologic study of 100 cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2015, 120, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchner, A.; Merrell, P.W.; Carpenter, W.M. Relative frequency of solitary melanocytic lesions of the oral mucosa. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2004, 33, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleti, M.; Mooi, W.J.; Casparie, M.K.; Van der Waal, I. Melanocytic nevi of the oral mucosa—No evidence of increased risk for oral malignant melanoma: An analysis of 119 cases. Oral Oncol. 2007, 43, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleti, M.; Leemans, C.R.; Mooi, W.J.; Van der Waal, I. Oral Malignant Melanoma: The Amsterdam Experience. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 2181–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisi, M.; Izzetti, R.; Gennai, S.; Pucci, A.; Lenzi, C.; Graziani, F. Oral Mucosal Melanoma. J. Craniofacial Surg. 2022, 33, 830–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Anderson, S.F.; Perez, E.M.; Townsend, J.C. Amelanotic Choroidal Nevus and Melanoma: Cytology, Tumor Size, and Pigmentation as Prognostic Indicators. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2001, 78, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, S.; Mussi, M.; Roda, M.; Pepe, F.; Schiavi, C. Conjunctival amelanotic nevus: Clinical and dermoscopic clues. Int. J. Dermatol. 2023, 62, E382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Khan, W.A.; Walke, V.; Patil, K. Primary Vaginal Amelanotic Melanoma: A Diagnostic Conundrum. Cureus 2021, 13, e20796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortuna, A.; Amaral, T. Multidisciplinary approach and treatment of acral and mucosal melanoma. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1340408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, V.; Cappello, M.; Megna, M.; Costa, C.; Villani, A.; Fabbrocini, G.; Marino, V.; Scalvenzi, M. Dermoscopic patterns of intradermal naevi. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2020, 61, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strazzulla, L.C.; Li, X.; Zhu, K.; Okhovat, J.P.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, C.C. Clinicopathologic, misdiagnosis, and survival differences between clinically amelanotic melanomas and pigmented melanomas. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.E.; McMeniman, E.K.; Duffy, D.L.; De’Ambrosis, B.; Smithers, B.M.; Jagirdar, K.; Lee, K.J.; Soyer, H.P.; Sturm, R.A. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of amelanotic and hypomelanotic melanoma patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohini, S.; Jayadev, C.; Venkatesh, R.; Nagesha, C.K. Utility of multimodal imaging in amelanotic choroidal nevus. BMJ Case Rep. 2022, 15, e253053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, V.; Janowska, A.; Faita, F.; Panduri, S.; Benincasa, B.B.; Izzetti, R.; Romanelli, M.; Oranges, T. Ultra-high-frequency ultrasound monitoring of plaque psoriasis during ixekizumab treatment. Skin Res. Technol. 2021, 27, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanuthai, K.; Theungtin, N.; Theungtin, N.; Thep-Akrapong, P.; Kintarak, S.; Klanrit, P.; Chamusri, N.; Sappayatosok, K. Pigmented Oral Lesions: A Multicenter Study. Eur. J. Dent. 2022, 16, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, F.; Rodrigo, J.P.; Cardesa, A.; Triantafyllou, A.; Devaney, K.O.; Mendenhall, W.M.; Haigentz, M., Jr.; Strojan, P.; Pellitteri, P.K.; Bradford, C.R.; et al. Update on primary head and neck mucosal melanoma. Head Neck 2016, 38, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaugars, G.E.; Heise, A.P.; Riley, W.T.; Abbey, L.M.; Svirsky, J.A. Oral melanotic macules. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1993, 76, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, M.J.; Flaitz, C.M. Oral mucosal melanoma: Epidemiology and pathobiology. Oral Oncol. 2000, 36, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Du, G.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, X.; Shi, L. Potential association between oral mucosal nevus and melanoma: A preliminary clinicopathologic study. Oral Dis. 2020, 26, 1240–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, A.; Narala, S.; Raghavan, S.S. Immunohistochemistry in melanocytic lesions: Updates with a practical review for pathologists. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2022, 39, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsie, S.J.; Sarantopoulos, G.P.; Cochran, A.J.; Binder, S.W. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2008, 35, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamiolakis, P.; Theofilou, V.; Tosios, K.; Sklavounou-Andrikopoulou, A. Oral verruciform xanthoma: Report of 13 new cases and review of the literature. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2018, 23, e429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, U.; Doddawad, V.; Sreeshyla, H.; Patil, R. Verruciform xanthoma: A view on the concepts of its etiopathogenesis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2013, 17, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belknap, A.N.; Islam, M.N.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Cohen, D.M.; Fitzpatrick, S.G. Oral Verruciform Xanthoma: A Series of 212 Cases and Review of the Literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2020, 14, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vered, M.; Wright, J.M. Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors: Odontogenic and Maxillofacial Bone Tumours. Head Neck Pathol. 2022, 16, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipsen, H.P.; Reichart, P.A.; Nikai, H.; Takata, T.; Kudo, Y. Peripheral ameloblastoma: Biological profile based on 160 cases from the literature. Oral Oncol. 2001, 37, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decani, S.; Quatrale, M.; Caria, V.; Moneghini, L.; Varoni, E.M. Peripheral Ameloblastoma: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.T.; Vargas, P.A.; Tomimori, J.; Lopes, M.A.; Santos-Silva, A.R. Linear verrucous epidermal nevus with oral manifestations: Report of two cases. Dermatol. Online J. 2020, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesi, D.; Ficarra, G. Oral Linear Epidermal Nevus: A Review of the Literature and Report of Two New Cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2010, 4, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tam, S.; Fu, S.; Xu, L.; Krause, K.J.; Lairson, D.R.; Miao, H.; Sturgis, E.M.; Dahlstrom, K.R. The epidemiology of oral human papillomavirus infection in healthy populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2018, 82, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, S.J. HPV-Related Papillary Lesions of the Oral Mucosa: A Review. Head Neck Pathol. 2019, 13, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleti, M.; Leemans, C.R.; Mooi, W.J.; Vescovi, P.; Van der Waal, I. Oral malignant melanoma: A review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2007, 43, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, B.F.; Carpenter, W.M.; Daniels, T.E.; Kahn, M.A.; Leider, A.S.; Lozada-Nur, F.; Lynch, D.P.; Melrose, R.; Merrell, P.; Morton, T.; et al. Oral muscosal melanomas. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 1997, 83, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.L.; Patel, S.G.; Huvos, A.G.; Shah, J.P.; Busam, K.J. Primary mucosal melanoma of the head and neck. Cancer Interdiscip. Int. J. Am. Cancer Soc. 2004, 100, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, J.; Clark, A. Pigmented Lesions of the Oral Cavity. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 35, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, N.; Mimura, M.; Kimijima, Y.; Amagasa, T. Clinical investigation of amelanotic malignant melanoma in the oral region. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 62, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, P.P.; Naumann, J.; Jarvis, M.C.; Wilkinson, P.E.; Ho, D.P.; Islam, M.N.; Bhattacharyya, I.; Gopalakrishnan, R.; Li, F.; Koutlas, I.G.; et al. Primary mucosal melanomas of the head and neck are characterised by overexpression of the DNA mutating enzyme APOBEC3B. Histopathology 2023, 82, 608–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.E.; Goellner, J.R. Amelanotic Melanoma: Cases Studied by Fontana Stain, S-100 Immunostain, and Ultrastructural Examination. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1988, 63, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodson, A.G.; Florell, S.R.; Boucher, K.M.; Grossman, D. Low rates of clinical recurrence after biopsy of benign to moderately dysplastic melanocytic nevi. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 62, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Izzetti, R.; Minuti, F.; Pucci, A.; Cinquini, C.; Barone, A.; Nisi, M. Amelanotic Melanocytic Nevus of the Oral Cavity: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1554. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15121554

Izzetti R, Minuti F, Pucci A, Cinquini C, Barone A, Nisi M. Amelanotic Melanocytic Nevus of the Oral Cavity: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(12):1554. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15121554

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzzetti, Rossana, Filippo Minuti, Angela Pucci, Chiara Cinquini, Antonio Barone, and Marco Nisi. 2025. "Amelanotic Melanocytic Nevus of the Oral Cavity: A Case Report and Literature Review" Diagnostics 15, no. 12: 1554. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15121554

APA StyleIzzetti, R., Minuti, F., Pucci, A., Cinquini, C., Barone, A., & Nisi, M. (2025). Amelanotic Melanocytic Nevus of the Oral Cavity: A Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics, 15(12), 1554. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15121554