Beyond the Middle Ear: A Thorough Review of Cholesteatoma in the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sources and Scope of the Literature

3. Results

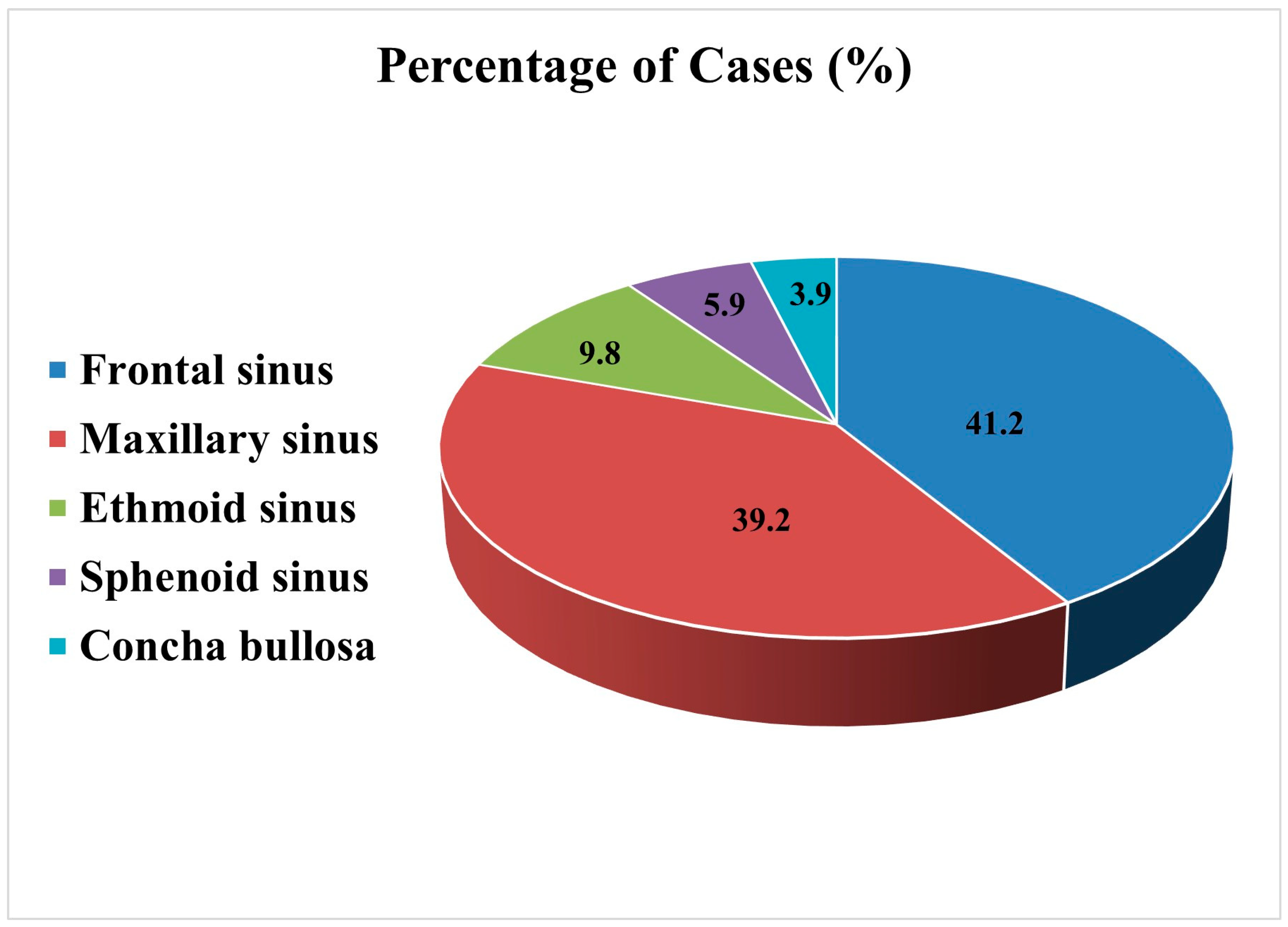

3.1. Anatomical Distribution and Clinical Outcomes

3.1.1. Frontal Sinus

3.1.2. Maxillary Sinus

3.1.3. Ethmoid Sinus

3.1.4. Sphenoid Sinus

3.1.5. Concha Bullosa

3.2. Gender and Age Patterns: Who Gets Affected and When?

3.3. Localization and Symptoms: Anatomy Drives the Agenda

3.4. Pathogenesis: Inflammation or Entrapment?

3.5. Cholesteatoma or Neoplasm? The Diagnostic Gray Zone

3.6. Challenging the Diagnosis: Seeing Through the Mucosal Fog

3.7. Imaging Matters: From Shadows to Structures

3.8. Surgical Treatment of Cholesteatoma in the Paranasal Sinuses

3.8.1. From Open Surgery to Endoscopy: A Paradigm Shift

3.8.2. Endoscopic Surgery: Panacea or Partial Fix?

3.8.3. Complications, Monitoring, and the Road Ahead

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCC | Squamous cell carcinoma |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| HPV | Human papilloma virus |

References

- Schürmann, M.; Goon, P.; Sudhoff, H. Review of potential medical treatments for middle ear cholesteatoma. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.N.A.; Elsharnouby, M.M.; Elbegermy, M.M. Nasal sinuses cholesteatoma: Case series and review of the English literature. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2023, 280, 743–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeggström, A.A. Ett funn av cholesteatoma i pannhulan. Hygiea 1916, 78, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, F.R. Primary cholesteatoma of the sinuses and orbit: Report of a case of many years’ duration followed by carcinoma and death. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1930, 12, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Whang, C.; You, J.; Park, H.; Geum, S.; Shin, S.; Ye, M. Squamous cell carcinoma arising from a cholesteatoma of the maxillary sinus: A case report. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 90, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, G.M. Cholesteatoma of the frontal sinus. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1937, 26, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, E.A. Epidermoid tumors of the frontal bone, sinus and orbit. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1950, 51, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, D.A.; Wallace, M. Carcinoma of the frontal sinus associated with epidermoid cholesteatoma. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1967, 81, 1021–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, T.C.; Schwartz, H.E. Cholesteatoma of the frontal sinus. Trans. Sect. Otolaryngol. Am. Acad. Ophthalmol. Otolaryngol. 1976, 82, 579–581. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, G.R.; Holt, J.E.; Davis, W.E. Late recurrence of a frontal sinus cholesteatoma. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1977, 86 Pt 1, 852–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniglia, A.J.; Villa, L. Epidermoid carcinoma of the frontal sinus secondary to cholesteatoma. Trans. Sect. Ophthalmol. Am. Acad. Ophthalmol. Otolaryngol. 1977, 84, 112–115. [Google Scholar]

- Campanella, R.S.; Caldarelli, D.D.; Friedberg, S.A. Cholesteatoma of the frontal and ethmoid areas. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1979, 88 Pt 1, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, A.N.; Colman, M.; Jayich, S.A. Verrucous carcinoma of the frontal sinus: A case report and review of the literature. J. Surg. Oncol. 1983, 24, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, M.L.; Montgomery, W.W. Primary and secondary keratomas of the frontal sinus. Laryngoscope 1984, 94 Pt 1, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, S.; Sørensen, C.H.; Stage, J.; Mouritzen, A.; Cayé-Thomasen, P. Massive cholesteatoma of the frontal sinus: Case report and review of the literature. Auris Nasus Larynx 2007, 34, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, B.; Mnejja, M.; Chakroun, A.; Achour, I.; Chakroun, A.; Charfeddine, I.; Ghorbel, A. Cholesteatoma of the frontal sinus. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2010, 127, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.C.; Liu, C.K.; Chen, M.L.; Chen, M.K. Removal of frontal sinus keratoma solely via endoscopic sinus surgery. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2010, 124, 1116–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoia, C.; Pusateri, A.; Carena, P.; Matti, E.; Galioto, S.; Benazzo, M.; Gaetani, P.; Pagella, F. Frontal sinus cholesteatoma with intracranial complication. ANZ J. Surg. 2015, 88, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurien, R.; Thomas, L.; Varghese, L.; Nair, B.R. Frontal sinus cholesteatoma: A masquerading diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2019, 12, e231495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejani, N.; Kshirsagar, R.; Song, B.; Liang, J. Evolving treatment of frontal sinus cholesteatoma: A case report. Perm. Med. J. 2020, 24, 19.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, D.C.; Santos, T.S.; Miranda Silva, V.C.; Costa, H.N.A.; Carvalho, C.M.F. Frontal sinus cholesteatoma presenting with intracranial and orbital complications: Diagnosis and treatment. Turk. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 60, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, C.P.; Sycamore, E.M. Cholesteatoma of the maxillary antrum. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1958, 72, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogorel, B.S.; Budd, E.G. Cholesteatoma of the maxillary sinus: A case report. Arch. Otolaryngol. 1965, 82, 532–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, J.S. Cholesteatoma of the maxillary antrum. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1966, 80, 1059–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K. Cholesteatoma of maxillary sinus. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1971, 85, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paaske, P.B. Cholesteatoma of the maxillary sinus (a case report). J. Laryngol. Otol. 1984, 98, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoff, R.S.; Pliskin, A. Cholesteatoma (keratoma) of the maxillary sinus: Report of a case. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1989, 47, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storper, I.S.; Newman, A.N. Cholesteatoma of the maxillary sinus. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1992, 118, 975–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, F.; Callanan, V.; Leighton, J.; Risdon, R.A. Congenital maxillary sinus cholesteatoma. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2000, 52, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, E.; Robertson, H. Cholesteatoma of the maxillary sinus. Ear Nose Throat J. 2005, 84, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanatha, B.; Nayak, L.K.; Karthik, S. Cholesteatoma of the maxillary sinus. Ear Nose Throat J. 2007, 86, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viswanatha, B. Cholesteatoma of the nose and maxillary and ethmoid sinuses: A rare complication of palatal surgery. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011, 90, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouhan, M.; Yadav, J.S.; Bakshi, J.; Saikia, U.N. Cholesteatoma of maxillary sinus: Mimicking as sinus tumor. Clin. Rhinol. Int. J. 2011, 4, 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Burić, N.; Jovanović, G.; Tijanić, M. Usefulness of cone-beam CT for presurgical assessment of keratoma (cholesteatoma) of the maxillary sinus. Head Neck 2013, 35, E221–E225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sozansky, J.; Josephson, J.S. Cholesteatoma of the maxillary sinus: A case report and review of the literature. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2015, 36, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, K.S. Cholesteatoma of maxillary sinus: What is the best surgical approach? J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, 963–966. [Google Scholar]

- Bourchom, W.; Jaruchinda, P. Cholesteatoma of the maxillary sinus. Ann. Clin. Case Rep. 2017, 2, 1417. [Google Scholar]

- Vakalapudi, S.; Majumdar, S.; Uppala, D. Cholesteatoma of maxillary sinus simulating neoplasia: A rare case report. Int. J. Appl. Basic Med. Res. 2021, 11, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, H.; Peng, L.; Niu, D. A double intranasal approach to treat cholesteatoma of the maxillary sinus: A report of two cases and a literature review. B-ENT 2022, 19, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingi, E.; Cingi, C. Ethmoidal cholesteatoma. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1991, 100, 424–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, F.C.; Barnett, J.C., Jr. Massive bifrontal epidermoid tumor. Surg. Neurol. 1992, 38, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, R.K.; Palmer, J.N. Epidermoids of the paranasal sinuses and beyond: Endoscopic management. Am. J. Rhinol. 2006, 20, 441–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohta, S.; Nishizawa, S.; Ryu, H.; Yokoyama, T.; Hinokuma, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Uemura, K. Epidermoid tumor in the sphenoid sinus–case report. Neurol. Med. Chir. 1997, 37, 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, S.; Smith, A.; Leppla, D.; Ilangovan, S.; Glick, R. Epidermoid cyst of the sphenoid sinus with extension into the sella turcica presenting as pituitary apoplexy: Case report. Acta Neurochir. 2005, 63, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanjanawasee, D.; Chaowanapanja, P.; Keelawat, S.; Snidvongs, K. Sphenoid sinus cholesteatoma—Complications and skull base osteomyelitis: Case report and review of literature. Clin. Med. Insights Case Rep. 2019, 12, 1179547619835182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çukurova, I.; Demirhan, E.; Karaman, Y.; Yigitbaşı, O.G. Extraordinary pathologic entities within the concha bullosa. Saudi Med. J. 2009, 30, 937–941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Michaels, L. Origin of congenital cholesteatoma from a normally occurring epidermoid rest in the developing middle ear. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 1988, 15, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez-Siller, J.C.; Wentland, C.; Bowers, K.; Litofsky, N.S.; Rivera, A.L. Squamous cell carcinoma of the temporal bone arising from cholesteatoma: A case report and review of the literature. J. Neurol. Surg. Rep. 2022, 83, e13–e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selleck, A.M.; Desai, D.; Thorp, B.D.; Ebert, C.S.; Zanation, A.M. Management of frontal sinus tumors. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 49, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, A.; Baredes, S.; Setzen, M.; Eloy, J.A. Overview of frontal sinus pathology and management. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 49, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Gender/ Age | Primary Symptoms | Trauma History/ Surgery | Management | Malignancy or Intracranial Complication | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spencer (1930) [4] | M/40 | Exophthalmos, decreased vision | Cranial trauma | Trepanation method (Krönlein) | Exposure of the right frontal lobe, paraplegia | SCC, death 14 years later |

| Coates (1937) [6] | M/51 | Purulent discharges, proptosis, orbital swelling | Cranial trauma | Orbital decompression, drainage of posterior orbital abscess, mass removal | Dura thickening due to chronic inflammation | No recurrence 12 months later |

| F/27 | Supraorbital edema, frontal headache | - | Sinusotomy via an external approach | Exposure of the dura mater, presence of granulation tissue, necrotic perforation of the anterior wall, subperiosteal abscess | The patient missed the follow-up 10 months later | |

| Thacker (1950) [7] | M/26 | Proptosis | Cranial trauma | External approach, Lynch-type incision | Mass in direct contact with the dura | Recurrence 5 years later |

| Osborn (1967) [8] | F/62 | Pain, proptosis/edema | Sinus surgery | Excision via extracranial approach | SCC 5 years after the surgery | Loss of consciousness, disorientation, brain invasion, death |

| Calcaterra (1976) [9] | M/44 | Proptosis | - | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Holt (1977) [10] | F/24 | Exophthalmos, loss of vision | - | External approach, supraorbital incision | Severe bone destruction, intact dura | Recurrence 30 years later |

| Maniglia (1977) [11] | M/67 | Frontal headache, nasal obstruction | - | Not reported | - | SCC |

| Campanella (1979) [12] | M/65 | Proptosis, double vision | - | Left supraorbital approach with an osteoplastic flap via an eyebrow incision | - | No recurrence 10 years later |

| M/46 | Frontal headache | - | Approach to the right frontal sinus using an osteoplastic flap | - | Not reported | |

| M/36 | Right eyelid edema | - | Exploration via an upper eyelid incision | Erosion of the right frontal bone, dura exposure | Death from a car accident 4 months later | |

| Newman (1983) [13] | M/70 | Blurred vision, proptosis | - | Approach to the right frontal sinus using an osteoplastic flap | Verrucous carcinoma, frontal lobe abscess | Death on the 7th postoperative day after abscess surgery |

| Hopp (1984) [14] | M/23 | Frontal headache | Mild forehead trauma | Approach to the frontal sinus with an osteoplastic flap | - | No recurrence 12 months later |

| Hansen (2007) [15] | M/80 | Frontal headache, tenderness on palpation, blurred vision, left eye proptosis | - | Sinus surgery, ethmoidectomy via an external approach | Erosion of the posterior wall of the frontal sinus, dura mater with a shiny, keratin-like appearance | Recurrence 10 months later |

| Hammami (2010) [16] | M/25 | Upper eyelid edema, fever, altered consciousness, generalized seizures | - | Frontal sinus approach via an eyebrow incision after bony flap removal | Bacterial meningo-encephalitis | No recurrence 5 months later |

| Lai (2010) [17] | M/53 | Rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, anosmia | - | Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (modified Lothrop procedure) | Extensive bone erosion, dura exposure | No recurrence 24 months later |

| Zoia (2018) [18] | M/32 | Frontal headache, painful frontal swelling, fever, eyelid edema | - | Endoscopic sinus surgery | Frontal lobe abscess | Recurrence 6 months later, re-operation |

| Kurien (2019) [19] | F/27 | Headache, forehead swelling | - | Endoscopic surgery of the nose and paranasal sinuses (Lothrop procedure) combined with an external approach via an incision along the hairline | Dura mater adherent to both the bone and the cholesteatoma at the sites of bone defects | No recurrence 6 months later |

| Tejani (2020) [20] | M/45 | Forehead and eyelid swelling | Repeated head injuries during childhood | Endoscopic sinus surgery | Dura exposure | Mild keratin remnants in the frontal sinus 2.5 years later; irrigation/follow-up |

| Goncalves (2022) [21] | F/68 | Headache, fever, right eyelid edema/ptosis, exophthalmos, conjunctival redness | Craniotomy, endoscopic approach for subcutaneous abscess of the frontal region | Draf III, external approach via an incision along the hairline | - | No recurrence 6 months later |

| Ahmed (2023) [2] | F/35 | Frontal headache | External approach to the right frontal sinus via an eyebrow incision | Endoscopic sinus surgery, external trepanation | - | No recurrence 24 months later |

| Author (Year) | Gender/ Age | Primary Symptoms | Trauma History/ Surgery | Management | Malignancy or Intracranial Complication | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mills (1958) [22] | F/65 | Left facial pain/swelling, rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction | - | Opening of an oroantral fistula, surgical excision, antrostomy | - | Not reported |

| Pogorel (1965) [23] | M/36 | Toothache, headache, swelling/pain of the left eye, diplopia, fever, following tooth extraction | - | Maxillary sinus antrostomy, Caldwell-Luc procedure | - | No recurrence 24 months later |

| Baxter (1966) [24] | M/20 | Left facial swelling | Nasal surgery for polyp removal | Caldwell Luc procedure | - | Not reported |

| Das (1971) [25] | F/55 | Facial pain, nasal obstruction | - | Caldwell Luc procedure | - | Not reported |

| Paaske (1984) [26] | M/76 | Facial pain, intermittent purulent discharge from the left nostril | Facial trauma, tooth extractions in the upper jaw | Caldwell Luc procedure | - | Not reported |

| Sadoff (1989) [27] | F/55 | Left facial swelling, nasal congestion | - | Nasal antrostomy | - | No recurrence 8 months later |

| Storper (1992) [28] | M/12 | Left facial swelling, pain in the upper jaw/hard palate, nasal obstruction, clear nasal discharge, periodic generalized headaches | - | Caldwell Luc procedure | - | No recurrence 8 months later |

| Vaz (2000) (congenital) [29] | F/1.5 | Right facial and intraoral swelling, snoring, epiphora | - | Inferior nasal antrostomy of the maxillary sinus | - | No recurrence, time interval not specified |

| Palacios (2005) [30] | M/57 | Left facial swelling | - | Not reported | - | Not reported |

| Viswanatha (2007) [31] | F/18 | Painless swelling of the left buccal region, nasal obstruction, intermittent headaches | - | Approach via an incision inside the mouth, beneath the lip | - | No recurrence 6 months later |

| Viswanatha (2011) [32] | M/10 | Left nasal obstruction, intermittent foul-smelling nasal discharge | Cleft lip/palate repair | Endoscopic sinus surgery | - | No recurrence 6 months later |

| Chouhan (2011) [33] | F/47 | Right nasal obstruction with discharge, facial swelling | - | Endoscopic sinus surgery | - | Not reported |

| Buric (2013) [34] | F/37 | Mild, dull pain and a sensation of swelling in the upper jaw in the area of the left molars | - | Intraoral excision | - | No recurrence 6 months later |

| Sozansky (2015) [35] | M/72 | Recurrent rhinosinusitis, nasal congestion, postnasal drip with colored mucous discharge | - | Endoscopic sinus surgery | - | No recurrence 13 years later |

| Jin (2016) [36] | F/34 | Facial pain, toothache, recurrent purulent discharge from the left nostril | Endoscopic sinus surgery | Caldwell Luc procedure | - | No recurrence 12 months later |

| Bourchom (2017) [37] | F/74 | Facial/hard palate swelling, nasal obstruction | - | Caldwell Luc procedure, middle nasal antrostomy | - | Death from vascular disease after surviving without recurrence for 18 months |

| Vakalapudi (2021) [38] | M/36 | Toothache, facial swelling, pus drainage | Tooth extraction | Biopsy and further referral to a maxillofacial surgery clinic | - | Not reported |

| Zhen (2022) [39] | M/64 | Nasal obstruction, postnasal discharge | Endoscopic sinus surgery | Endoscopic sinus surgery | - | No recurrence 32 months later |

| M/31 | Swelling of the right buccal region, obstruction of the right nasal cavity, toothache, epiphora | - | Endoscopic sinus surgery | - | No recurrence 12 months later | |

| Kim (2024) [5] | M/40 | Dull pain in the left orbital cavity, foul-smelling nasal discharge | - | Caldwell Luc procedure, Endoscopic sinus surgery | - | SCC, radio-chemotherapy, no recurrence 1 year later |

| Author (Year) | Gender/ Age | Primary Symptoms | Trauma History/ Surgery | Management | Malignancy or Intracranial Complication | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campanella (1979) [12] | M/48 | Painless swelling on the medial side of the right eye | Nasal surgery | Lateral rhinotomy | - | No recurrence, follow-up duration not specified |

| Cingi (1991) [40] | F/16 | Painful, progressive swelling of the right eye, proptosis | - | Lateral rhinotomy | - | No recurrence 26 months later |

| Barnett (1992) [41] | M/76 | Transient episode of confusion/disorientation, frontal area protrusion, conductive hearing loss, anosmia | - | Craniotomy | Bilateral displacement of the frontal lobes, hyperplastic lesions of the skull, anterior compression of the ventricles, mild hypodense lesion in the white matter posterior to the mass | No new neurological deficits, with impressive reexpansion of the frontal hemispheres |

| Chandra (2006) [42] | F/22 | Headache | Frontal trauma, motor vehicle accident, transsphenoidal hypophysectomy of a macroadenoma | Endoscopic sinus surgery, trepanation | - | No recurrence 14 months later |

| Ahmed (2023) [2] | F/17 | Medial canthus swelling, headache, symptoms of allergic rhinosinusitis | - | Endoscopic sinus surgery | - | No recurrence 24 months later |

| Author (Year) | Anatomical Site | Gender/ Age | Primary Symptoms | Trauma History/ Surgery | Management | Malignancy or Intracranial Complication | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ohta (1997) [43] | Sphenoid sinus | M/36 | Diplopia, sixth cranial nerve paresis | - | Transsphenoidal approach | Extension toward the clivus and the brainstem | Not reported |

| Sani (2005) [44] | M/25 | Headache, diplopia, reduced visual acuity, upper eyelid ptosis, third cranial nerve palsy | - | Transsphenoidal approach | Extension into the sella turcica presenting as pituitary apoplexy | Complete neurological recovery 3 months later | |

| Kanjanawasee (2019) [45] | F/82 | Chronic headache, fever | - | Transsphenoidal approach | Skull base osteomyelitis | Death | |

| Cukurova (2010) [46] | Concha bullosa | F/81 | Headache, diplopia, eye proptosis, nasal obstruction | - | Endoscopic sinus surgery | - | No recurrence 14 months later |

| Ahmed (2023) [2] | F/24 | Nasal obstruction, external swelling beneath the left eye | - | Endoscopic sinus surgery | - | No recurrence 24 months later |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Athanasopoulos, M.; Samara, P.; Mastronikolis, S.; Mastronikoli, S.; Danielides, G.; Lygeros, S. Beyond the Middle Ear: A Thorough Review of Cholesteatoma in the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15121461

Athanasopoulos M, Samara P, Mastronikolis S, Mastronikoli S, Danielides G, Lygeros S. Beyond the Middle Ear: A Thorough Review of Cholesteatoma in the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses. Diagnostics. 2025; 15(12):1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15121461

Chicago/Turabian StyleAthanasopoulos, Michail, Pinelopi Samara, Stylianos Mastronikolis, Sofianiki Mastronikoli, Gerasimos Danielides, and Spyridon Lygeros. 2025. "Beyond the Middle Ear: A Thorough Review of Cholesteatoma in the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses" Diagnostics 15, no. 12: 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15121461

APA StyleAthanasopoulos, M., Samara, P., Mastronikolis, S., Mastronikoli, S., Danielides, G., & Lygeros, S. (2025). Beyond the Middle Ear: A Thorough Review of Cholesteatoma in the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses. Diagnostics, 15(12), 1461. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics15121461