2.1. Patient “0”—Caucasian 52-Year-Old Healthy Male

Though an adult at presentation, the case patient shared a harrowing story of painful nocturnal respiratory arrests that sporadically afflicted him throughout his childhood and youth. He felt he came within a breath of losing his life each time. Starting at 7 years old one night, he suddenly awoke gasping (mouth opened involuntarily, unable to inspire) with bilateral rib pain that felt like someone had picked him up from behind in a tight bearhug. The pain was characterized as pleuritic and cramp-like in nature. He did not recall being ill at the time or sharing the bed; however, did have many risk factors overlapping with those identified in SIDS (e.g., household cigarette smoke, cold climate, nocturnal sweating, deep sleeper with tendency to pull blankets over shoulders and head and a history of severe gastroesophageal reflux [

2], requiring hiatal hernia repair at 18 months of age). When he tried inspiring forcefully, it was met with more pain and complete resistance to airflow. Realizing it was futile, he experimented—as only a young child can despite the duress of nearing death—learning he could still exhale. Forced inspirations again futile, he felt he then saved his life by exhaling, followed quickly by three short burst (staccato) high-pressure inhalations “like a pilot breathing in a centrifuge” (

Supplementary Video S1). Immediately, the pain and obstruction disappeared, and normal breathing resumed. He then went back to sleep as if nothing had happened. With sporadic recurrences over the next ten years, always at night while asleep, he reemployed this breathing technique and even learned to do it in his sleep. He commented, “Over the years I became intricately aware of this thing, fearing the pain and inability to breathe, learning to abort it by recognizing its [prodromal painful rib fasciculations] and quickly taking in a breath before the big pain would kick in [at end-inspiration]” (obviating the need for the rescue breaths). As he grew older, he just assumed this happened to everybody, perhaps minimizing the traumatic events as a psychological defense mechanism. Sadly, he never told anyone until 45 years later. For more details, see Patient’s Perspective in

Supplementary Materials.

Although beyond the scope of this paper, most items in the differential diagnosis (

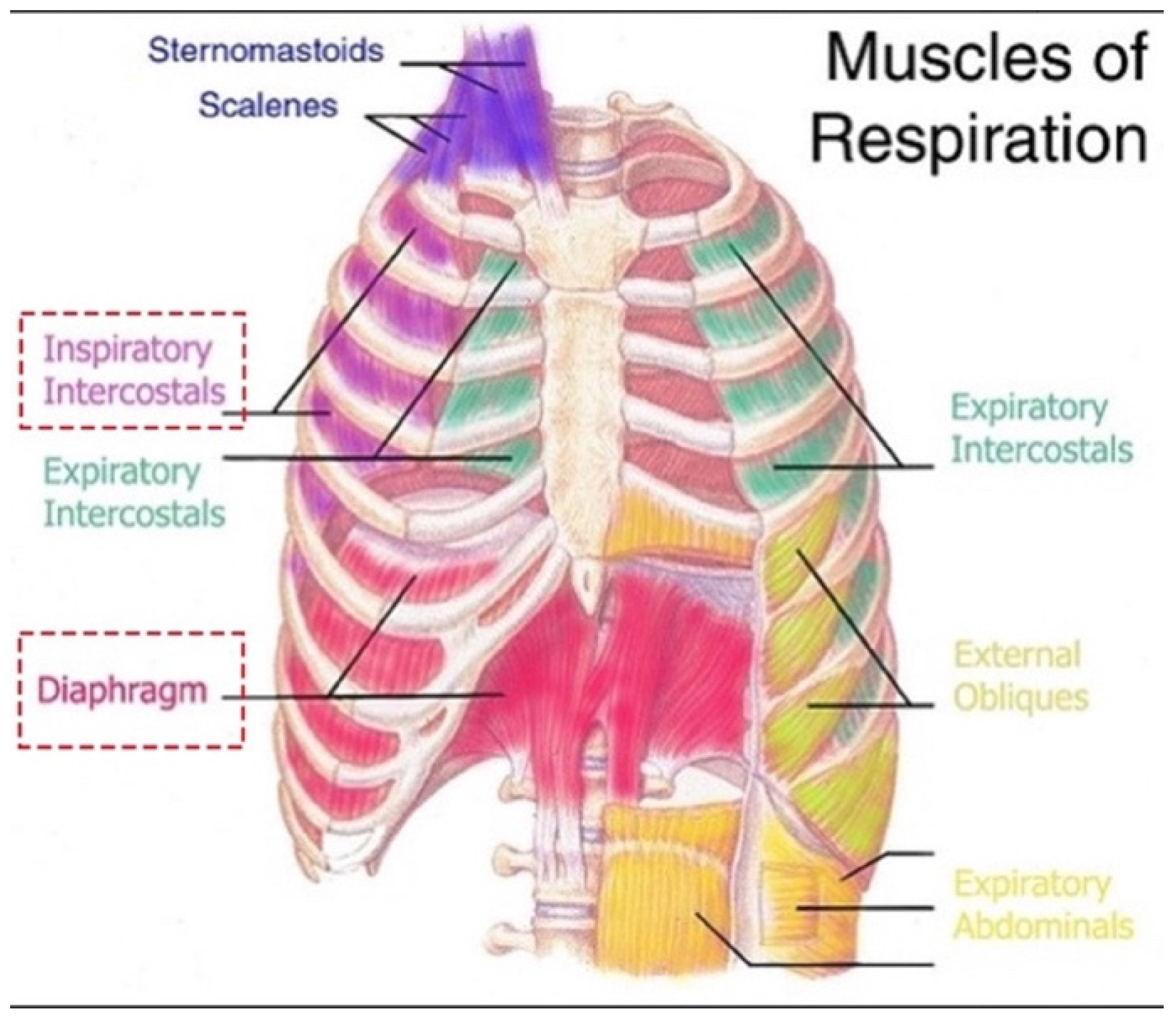

Table S1) were easily excluded using clinical reasoning of key historical features: spontaneous sudden-onset recurrent nocturnal cramp-like bilateral rib (bearhug) pain with complete inspiratory arrest. The most common causes of nocturnal respiratory distress in children, such as panic attacks, sleep paralysis, night terrors, seizures, bronchospasm, laryngospasm and OSA, were ruled out simply because they do not feature intense pain. Similarly, painful conditions of the ribs or chest do not include a 100% airway obstruction. This left the novel diagnosis of bilateral cramps of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles (

Figure 1). Alternatively, the entire story could have been fictitious or related to child abuse (both denied). However, the patient’s account was exceptionally detailed and consistent throughout, supporting his authenticity and credibility. Given it is possible a cramp could localize to a region within a muscle body, yet apnea occurred (failure of the entire inspiration movement), it was necessary to introduce the term, contracture. Thus, diaphragm cramp-contracture was adopted. It was hypothesized that loss of diaphragm mechanical pump function by DCC induced a state equivalent to acute bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis (explaining the patient’s inspiratory arrest).

Why this was medically unheard of could relate to extremely high mortality (few survivors). Also, if there are any, they would be preverbal children unable to describe symptoms or older ones, like the case patient, who repressed or were reluctant to share memories. Lastly, it occurs during deep sleep, making recall and differentiation of reality from dreaming less clear.

Table A1 provides further speculation as to how DCC might have evaded detection historically.

2.2. Evidence for Putative DCC in Medical Literature

Next, the SIDS and SUDC literature bodies were investigated, looking to rule out DCC. The search revealed Poets et al.’s (1999) [

3] report on nine preterm infants aged 1–6 months who had succumbed to SIDS and had basic home cardiorespiratory “memory monitor” recordings of their final moments (heart rate and respiratory movements but not airflow or oxygen saturations). Cause of the monitor alarm was bradycardia in seven and apnea in two. Identical to the case patient’s report, terminal gasping and inspiratory arrest had occurred (in seven infants). Gasping duration ranged from 3 s to 11 min. Also, it was ineffective, whereby efforts to inspire were unsuccessful in reestablishing airflow and reversing the bradycardia. This indicated an airway obstruction existed, but to this day, has never been identified other than speculated over laryngospasm or bronchospasm. Furthermore, the authors explained how gasping in mammals occurs when PaO

2 falls under 5–15 mmHg (normal range in infants is 50–80 mmHg) and is elicited only by hypoxemia, not hypercapnia or acidosis. This suggested severe hypoxemia was present before the monitors had alarmed. As prolonged central apneas were not detected, potential causes were reduced to blunted chemoreceptor responses, hypoventilation and breathing exhaled gases.

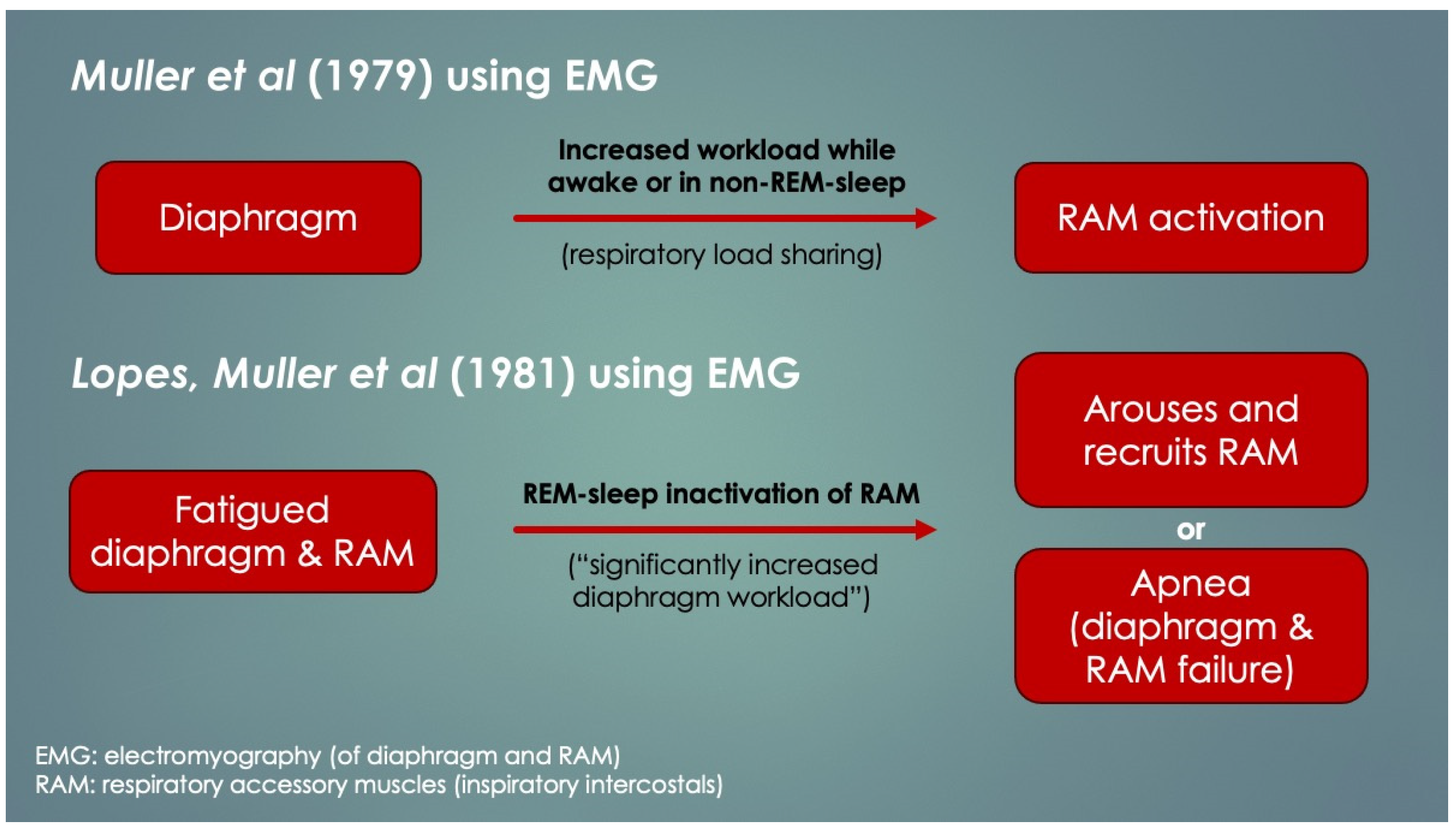

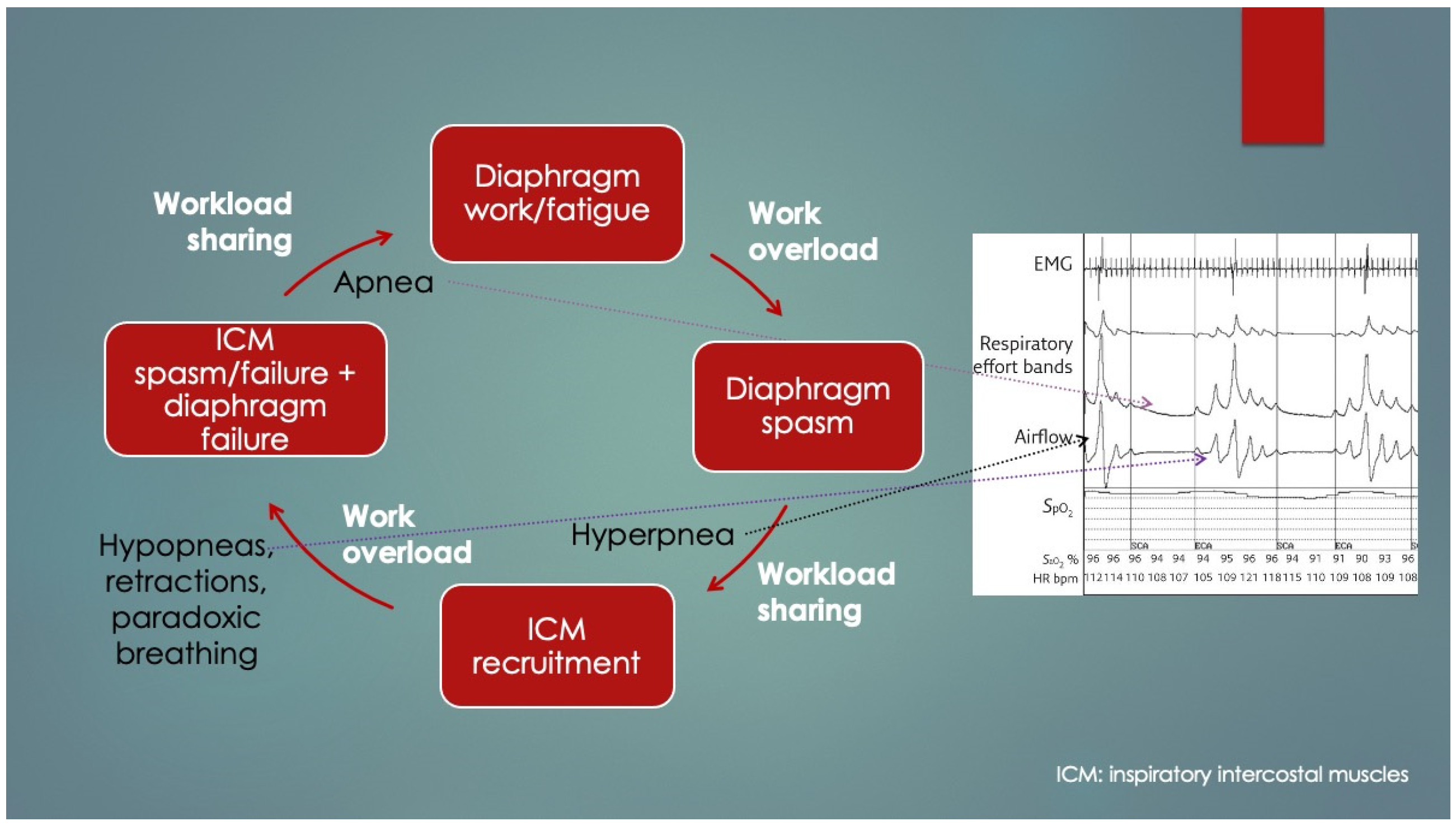

Another crucial paper was by Lopes et al. (1981) [

4], who determined diaphragm fatigue existed in 12 of 15 otherwise healthy preterm infants at mean 19.9 ± 13.7 days age using surface electromyography (EMG) of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles (ICM). Moreover, two different patterns of response to fatigue were observed: as opposed to infants who recruited their ICM, apneas occurred in those that did not. Some infants with prolonged apneas required tactile stimulation (presumably to wake them to breathe), and failing that, short-term CPAP and even mechanical ventilation (MV). Normally, respiratory accessory muscle (RAM) recruitment, which includes the ICM, occurs by a process known as respiratory load sharing (or load dependence), wherein ventilatory workload is diverted from the diaphragm to ICM as diaphragm fatigue sets in (and vice versa) [

5]. In fact, rib retractions, commonly observed in children with respiratory distress, provide a direct visual cue of ICM activation secondary to diaphragm fatigue. Another physical sign of diaphragm fatigue (and outright failure) is paroxysmal breathing or thoraco-abdominal asynchrony. It also occurs in diaphragm paralysis and paresis, whereby ventilation is powered or assisted by RAM contractions, respectively. With inspiration, the abdomen becomes drawn in instead of descending and expanding. EMG had determined the apneas involved simultaneous failure of both ICM and diaphragm (preceded by worsening fatigue), and it occurred only when ICM did not take over the work of breathing. The authors discussed the role of REM sleep—when there is physiologic CNS inhibition of skeletal muscles including the ICM but not diaphragm—however, it could not be concluded because sleep state was not measured. Nevertheless, in extension of this line of interpretation, it appears REM sleep predisposed to the fatigue-associated apneas, and they had occurred by failure of both ICM and diaphragm (that is,

peripheral malfunction). Furthermore, those who had arousal, presumably by hypoxia- or hypercapnia-mediated chemoreception (or tactile stimulation), probably reactivated their ICM, thereby avoiding the apnea. What remains undetermined however, was the reason for the lack of arousals in others as well as the mechanism of diaphragm failure itself. Lastly, had traditional sleep study chest impedance belts been used, these apneas would have been classified as central, because of absent respiratory movements.

Figure 2 summarizes these findings and is consistent with other authors’ conclusions [

6,

7,

8].

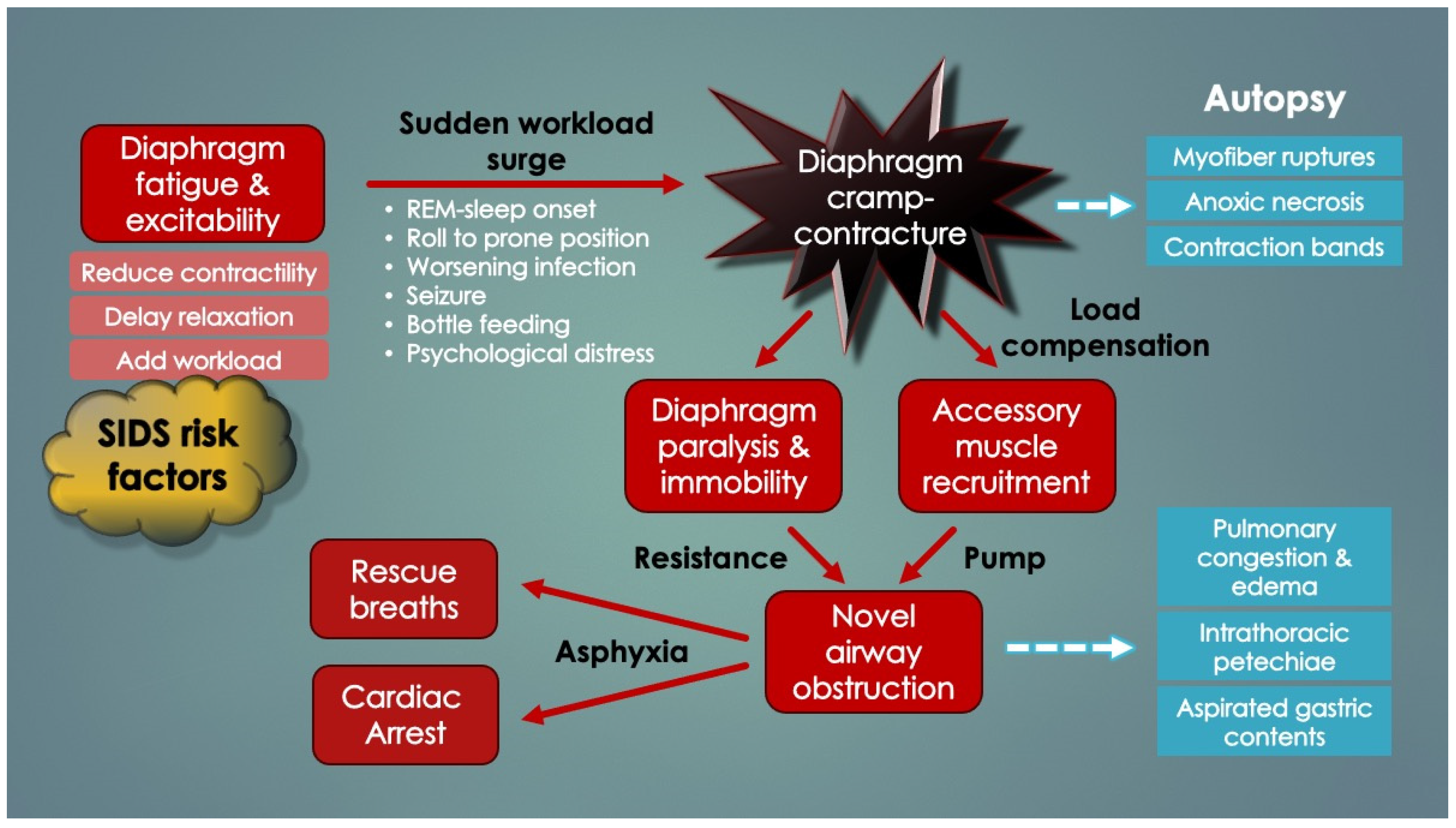

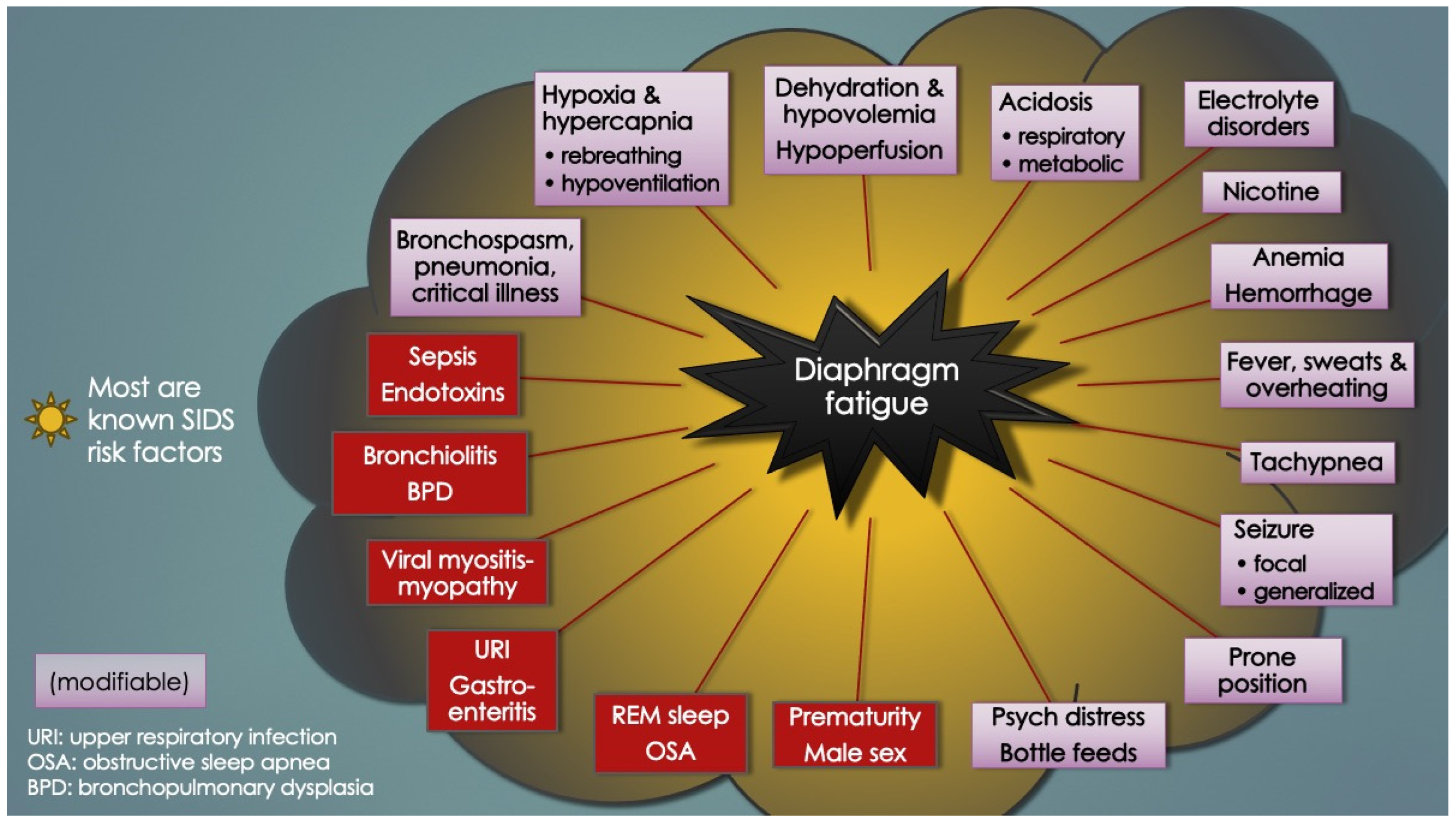

In support of peripheral apnea in SIDS was evidence presented by Siren and Siren (2011) in their SIDS-Critical Diaphragmatic Failure hypothesis (a review article). They postulated that several diaphragm fatiguing (and added workload) factors cumulatively increase the risk of diaphragm failure in SIDS, including non-lethal viral infections, prone positioning, male sex, hypoxia, hypercapnia, high altitude, bottle feedings as well as underdeveloped RAM and their inactivation in REM sleep [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Others included hypomagnesemia, overheating and tobacco smoke. Importantly, all are SIDS risk factors. In support of DCC here though is the sudden and unpredictable nature of SIDS. Suddenness, without prodromal respiratory distress, is in support of a DCC event rather than gradual respiratory failure. Regardless, the Lopes group put it best in 1981 as, “The neural [CNS] basis for apnea is so deeply entrenched that it is difficult to accept that some apnea may be due to [peripheral] respiratory muscle failure”.

2.3. Diaphragm Hyperexcitability Disorders (DHD)

Further literature review revealed numerous contraction abnormalities of the diaphragm, most importantly, diaphragm flutter (van Leeuwenhoek’s disease) [

12] and respiratory flutter. Diaphragm flutter (DF), thought to be rare, involves rhythmic involuntary contractions of the diaphragm superfluous to those that occur with normal neural (CNS-mediated) autonomic breathing (as opposed to volitional breathing, which involves a separate neuroanatomic pathway also carried by the phrenic nerves). Respiratory flutter denotes excitation of the accessory muscles such as the rectus abdominae and ICM in addition to the diaphragm. Immediately, its existence alone demonstrated how anatomically disparate groups of inspiratory muscles can simultaneously develop pathological excitation (supporting the hypothesis that cramping of both diaphragm and ICM caused the case patient’s symptoms) [

13]. In that paper, respiratory flutter in three full-term neonates was reported as an “underrecognized cause of respiratory failure”, diagnosed by respiratory inductive plethysmography (RIP) and fluoroscopy. Within hours of birth, all developed ventilatory distress involving stridor, grunting, rib retractions, and inspiratory ratchetlike or fluttering chest movements requiring temporary CPAP or MV. Chlorpromazine, a typical antipsychotic medication, helped abate the flutter in all three. However, in another report, DF was well tolerated in three babies of mean 12-weeks’ age (gestational age unknown) with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) bronchiolitis [

14]. Notably, all are SIDS risk factors (including young age), suggesting a possible link between flutter and SIDS. Aside from postconceptional age though, it is uncertain why there was such a difference in clinical presentations between the patients reported in the two papers.

Numerous case reports of other pathological excitation states (neuromuscular irritability) of the diaphragm were found on review, and these were broadly classified under single contraction phenotypes (e.g., hiccups and spasms) [

15,

16] or arrhythmias (e.g., low and high frequency flutter and fibrillation) [

17,

18]. Examples of such hereby termed “diaphragm hyperexcitable disorders” (DHD) in addition to hiccups, spasms, flutter, and fibrillation were diaphragmatic and respiratory tics, fasciculations, palpitations, myoclonus, tremor and Belly Dancer’s dyskinesia. Summed up, however, it can be seen in

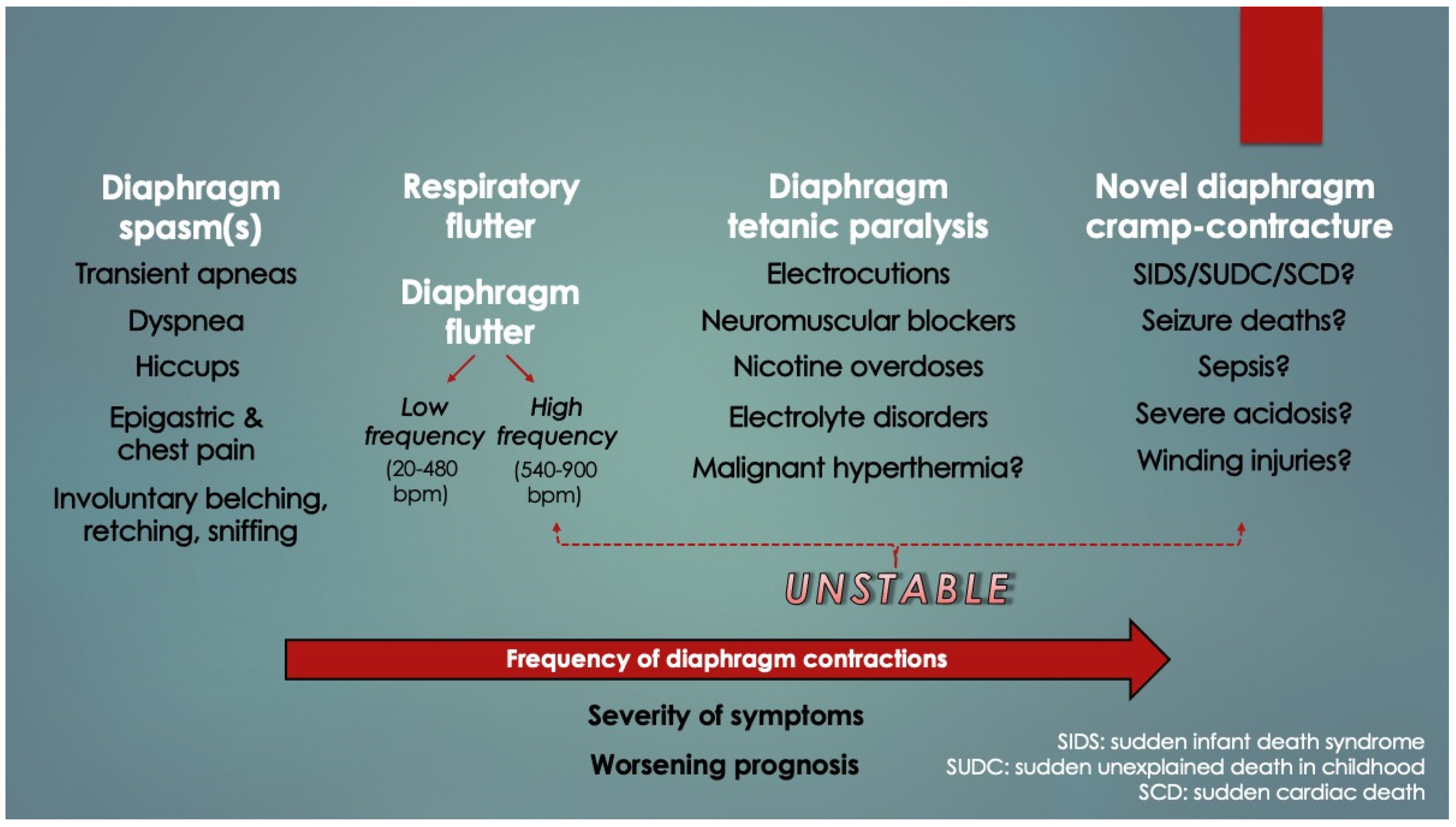

Figure 3 that DHDs appear to present along a frequency spectrum of worsening symptoms and prognoses. The higher the frequency, the more clinically unstable is the patient. This is a novel finding. DCC, which could represent a very high-frequency DHD akin to tetany, might also belong to the spectrum; however, given extremely high mortality with few survivors, these cases would have inadvertently been excluded by clinical studies (an inverse form of survivorship bias, or mortality bias).

Tobacco smoke exposure is a well-known SIDS risk factor. Nicotine poisonings in young children, even from ingesting snuff box scrapings, have led to rapid deaths from respiratory arrest (under 30 min). It was not centrally mediated [

19]. Rather, it occurred by peripheral paralysis from a sustained diaphragmatic spasm (essentially a tetanic cramp-contracture) [

20,

21]. Therefore, in infants exposed to subtoxic nicotine levels from household tobacco smoke, it is possible the threshold for diaphragm excitation is lowered (by respiratory muscle fatigue) [

22]. Similarly, nondepolarizing neuromuscular blockers like succinylcholine, commonly used to facilitate endotracheal intubation, also induce peripheral respiratory arrest; therefore, both were placed at the most severe position in the spectrum (under tetanic paralysis). In addition, some fatal electrocutions also occur by tetanic contractions of the respiratory muscles (not just cardiac arrhythmias); thus, this too was included [

23,

24]. Deaths from severe metabolic acidosis (in diabetic ketoacidosis [

25,

26] and lactic acidosis [

27]), malignant hyperthermia [

28], botulism [

29], rabies [

30] and tetanus [

31] also appear to occur by peripheral respiratory arrest, even sepsis too (vide infra). Notably, the heart also demonstrates sensitivity to acidosis, as demonstrated by a decrease in threshold for ventricular fibrillation [

32].

The etiologies of DHD are extensive and beyond the scope of this paper; however, it is important to note that pain and psychological distress are inciting causes at all ages [

17]. Feeding young children can be difficult at times, sometimes requiring forced effort, and this strenuous activity has been associated with apneic, SIDS-like awake deaths [

33]. Similarly, hypoxemic episodes in infants occurred with feeding as well as with anger, handling and noxious triggers like pain, airway suctioning, and loud noises [

34,

35]. This is in striking similarity to life-threatening cyanotic episodes reported in six infants with histories of recent seizures (suggesting a common mechanism with SUDEP; vide infra) [

36]. All of this supports the notion that stress-induced diaphragm excitation could cause serious respiratory symptoms, sometimes fatal. [Interestingly, by extension, increased diaphragmatic muscle tone in high-stress situations could physically squeeze on the traversing esophagus (and stomach), leading to the commonly experienced gastric symptoms of anxiety, including “butterflies”, epigastric discomfort, nausea, vomiting, belching and dyspepsia. This would represent a novel connection between mind and body].

Table 1 lists the various causes of respiratory muscle (Type II, hypercapnic) failure obtained by literature review.

Importantly, it was recognized that diaphragm-related respiratory insufficiency and failure was an underrecognized cause of serious morbidity and mortality in all ages, ranging from fatal soft tissue injuries of the neck (acute bilateral phrenic neuropathies) [

53] to heat stroke/hyperthermia [

28,

73], and terminal COVID-19 infections (acute diaphragm myopathy) [

47]. Other important causes included septic, hypovolemic, and cardiogenic shock (vide infra). Categorization could be made by organ involvement (CNS, phrenic nerve(s), diaphragm, or accessory muscles) as well as laterality, rapidity of onset and degree of weakness (complete paralysis versus paresis). For example, whereas some electrical injuries and cervical spine transections induced simultaneous, sudden and complete bilateral paralysis of both diaphragm and RAM, isolated diaphragm weakness occurred by direct abdominal trauma or phrenic nerve injuries (e.g., nerve tractions in birth trauma or chiropractic manipulations). In the very young (neonates), acute bilateral diaphragm paralysis (DP) despite functional RAM, induced critical Type II failure that was followed within minutes by cardiac arrest and death unless reversed by ventilatory support [

54,

59,

60]. This supports the argument that the very young, functional RAM cannot independently ventilate the lungs (when the diaphragm has failed). However, older infants survived probably because their maturing RAM tolerated the added workload. This also provides a compelling explanation why infants aged 2–4 months are at highest risk for SIDS (and not older): underdeveloped, weaker RAM. Older infants have had time for RAM maturation through load-dependent recruitment and training. With this classification scheme, it became evident that acute DP can be immediately fatal when it is bilateral, neurologically complete and occurs in those with weak, paralyzed or cramped RAM (

Figure 4). Also, apnea duration needs to be sufficient as to induce critical hypoxemia and secondary cardiac arrest (only 1–2 min) [

74]. These too are novel findings.

Death by DCC in young infants satisfies these criteria because the RAM are weak and the effective DP is bilateral and probably complete (i.e., diaphragm fully inactivated by contracture). It is also paroxysmal (sudden and unexpected), just like SIDS and many other child deaths. Lastly, the process is silent, rapid and unwitnessed in most cases (obviating resuscitation efforts).

Table 2 similarly lists the causes of diaphragm fatigue (and increased ventilatory workloads) in infants ascertained upon literature review. Importantly, most, if not all, were known SIDS risk factors (or closely related to them). It should also be pointed out that, as opposed to diaphragm weakness, diaphragm fatigue is reversed by rest. Diaphragm fatigue or dysfunction (DD) is also referred to here as diaphragm insufficiency.

2.4. Diaphragm Excitation in Infants with Respiratory Instability

The greatest pathologic threat to infants is respiratory, and sleep is an especially vulnerable state. This is particularly concerning not only because they disproportionally spend their time sleeping, but most of it is active (REM) sleep, a stage associated with more respiratory instability. In living infants, this is observed as transient apneas and hypopneas (shallow breaths) as well as periodic breathing, increased arousals and hypoxemic episodes (HE).

Recurrent HE predispose to serious long-term morbidity such as cerebral palsy, retinopathy, blindness, deafness, poor growth, neuro-developmental delays and pulmonary hypertension with cardiomyopathies. Mortality is higher, including by sudden respiratory arrests in RSV bronchiolitis [

91] and sudden unexpected deaths, even as late as 18 months of age, if not longer (consistent with SIDS and SUDC, respectively) [

35,

120]. It is also more common in those with chronic conditions such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cerebral palsy and neuromuscular diseases, like muscular dystrophies and congenital myopathies.

Some HE are not visually apparent, whereas others may exhibit cyanosis, pallor, hypotonia, loss of consciousness or seizures. Simultaneous behaviors include

silent squirming, kicking, grimacing, writhing and bearing down, sometimes followed by hiccups (diaphragmatic contractions) [

34]. Unusually, these behaviors are associated with crying, so the silence supports the case patient’s report that inspiratory arrest had occurred. This is corroborated by the work of Southall et al. (1990) [

35], who found prolonged absence of inspiratory efforts was common among 51 infants with recurrent cyanotic HE. Expirations still occurred, also consistent with our case. It is important to point out that that most HE are not preceded by seizures.

Defined as oxygen saturations under 88% for over 10 s, HE in one study lasted from tens of seconds to two minutes, occurring up to hundreds of times daily in spontaneously breathing, former preterms at 44 ± 21 days of age [

121]. They even occur in infants receiving mechanical ventilation, as exhibited by forced expirations, hypopneas and reliance on ventilator breaths associated with doubling of pulmonary resistance and reduced lung compliance of unknown origin (with simultaneous increases in gastric and esophageal pressures) [

122].

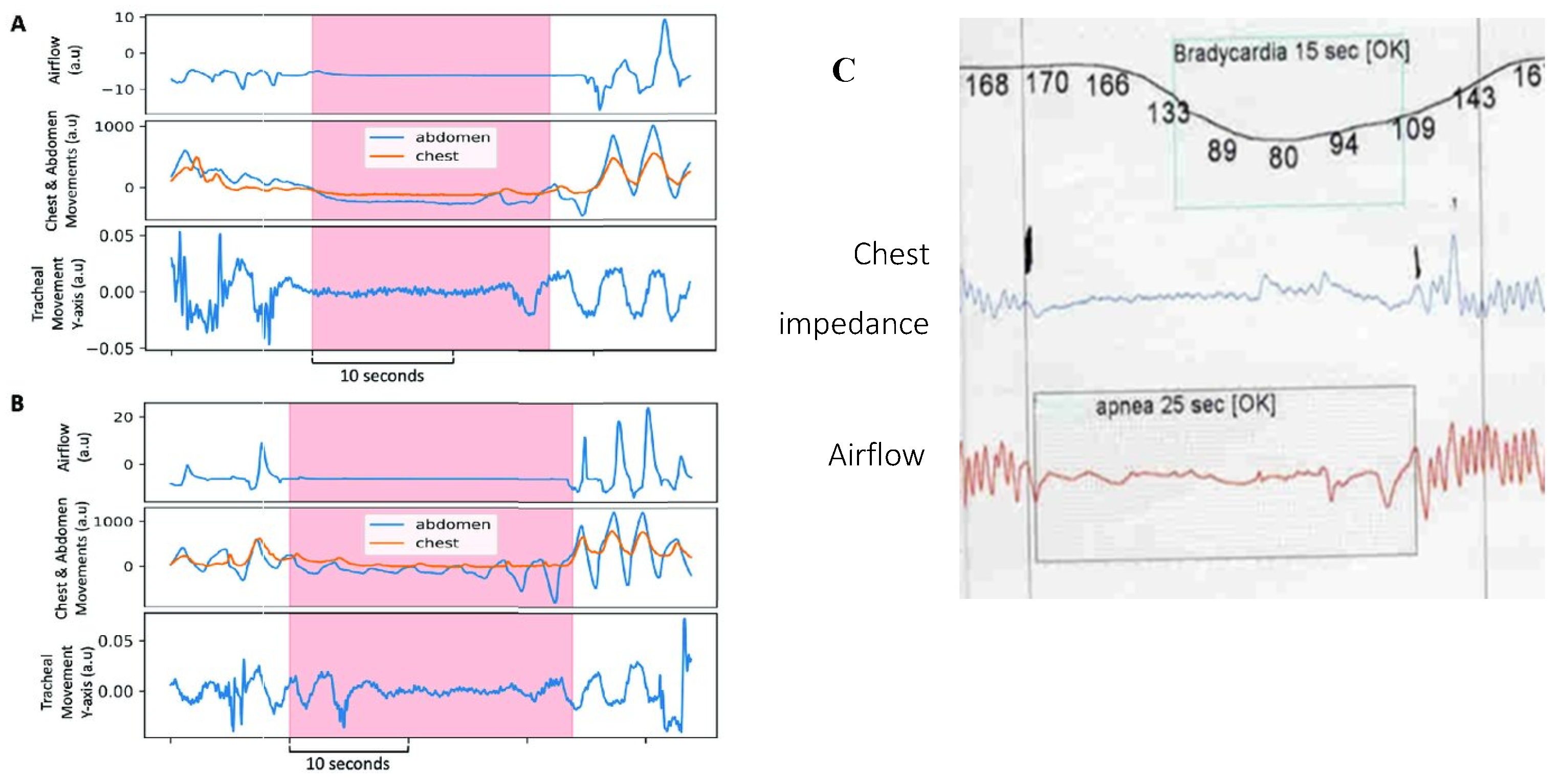

Respiratory instability is thought to be caused by abnormal chemoreception and immature development of the neural control of breathing, worsened by underdevelopment of the lungs (primarily, surfactant deficiency). However, some HE appear to occur by “active” (voluntary) abdominal muscle contractions (causing forced expirations and hypopneas), sometimes followed by breath-holding (short apneas) [

123,

124]. As seen in

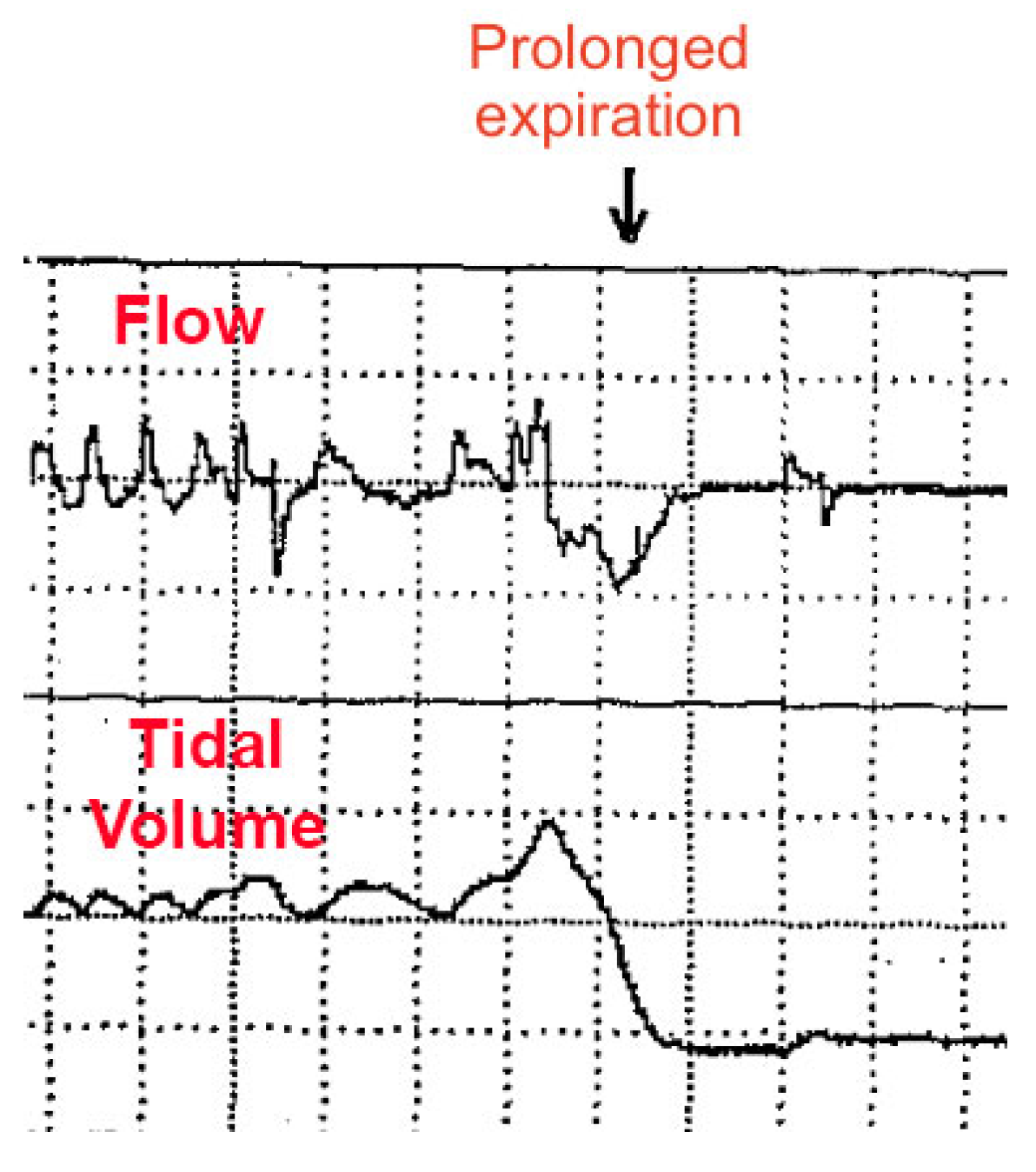

Figure 5, an abnormal respiratory waveform can manifest: a prolonged expiration (or prolonged expiratory apnea). Importantly, this occurs just at the end-expiration phase of the respiratory cycle (identical timing to DCC onset as reported by our patient).

Curiously, almost nothing is mentioned in the literature about the vital muscles that power respiration, despite compelling reports from the late 70’s indicating infants were “very close to the threshold of fatigue” [and failure] [

6]. Diaphragm fatigue occurs by a number of factors unique to very young compared to older infants: (1) highly compliant, cartilaginous ribcage, which reduces ventilatory efficiency; (2) less efficient RAM contributions because of less conditioning and anatomical differences (worsened in REM sleep by CNS inhibition); (3) decreased range of pump displacement due to diaphragm flattening; (4) fewer fatigue-resistant, slow-twitch diaphragm myofibers; and (5) lower total cross-sectional area of all myofiber types [

75]. Also, at any age, anything that increases work of breathing (or respiratory rate), like REM sleep, a roll to prone position, pain, psychological distress, forced bottle feedings, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, or pulmonary infections, exacerbates the fatigue, even sepsis and severe acidosis (evident as Kussmaul’s hyperpneic, labored respirations to “blow off” CO

2). The latter two also directly impair diaphragm contractility and relaxation (vide infra). In addition, anemia, a known risk factor for apnea of prematurity [

125], as well as apparent life-threatening events in infants [

112] and breath-holding spells in older children [

126], could explain these apneas simply because the reduced blood oxygen-carrying capacity exacerbates DD, particularly under times of increased physiologic demand. Clearly, the causes of DD-induced respiratory instability in infants (and proposed ventilatory failure) are complex and multifactorial, in keeping with the host of events thought to lead up to a sudden unexpected infant death.

Another held mechanism of HE is hypoxic (and hypercapnic) ventilatory depression (HHVD). The process, exacerbated in REM sleep, is thought to be from central causes. Normally, the compensatory (“CNS feedback”) response to hypoxemia or hypercapnia in mammals is by an increase in minute ventilation (V

E = respiratory rate x tidal volume). This happens in both adults and infants, but after an initial 1–2 min compensatory increase in infants (and about 20 min in healthy adults, depending on degree of hypoxia or hypercapnia), it is suddenly followed by a prolonged decrease (or depression) of V

E by a reduced respiratory rate. It has been a mystery why this presumed neural response is dysfunctional. Instead, it hereby appears HHVD might actually be caused by the reduced work output of diaphragm fatigue (insufficiency). It just takes longer to appear in adults because their mature, conditioned respiratory muscles are less vulnerable to fatigue. The process is simple: persistent hypoxia or hypercapnia (e.g., from breathing exhaled gases or hypoventilation) combined with acidosis (from both respiratory and metabolic types) induce DD, leading to reduced alveolar ventilation, which further compounds the hypoxia, hypercapnia, and respiratory acidosis in positive feedback cycles. The slow onset yet progressively worsening hypoxia of an unstable DD feedback cycle during sleep would explain the hypoxemic gasping seen in the Poets’ SIDS victims (where it preceded gasping, bradycardia and apnea alarms) [

3]. As we shall see, repeated HE by this mechanism could be responsible for myopathic changes seen in the diaphragms of SIDS victims.

In vivo analyses of ventilatory mechanics have determined that the dysfunctional drop of respiratory rate in HHVD occurs by a prolongation of the expiratory phase (T

E) of the breathing cycle. This too is thought secondary to CNS immaturity. However, in hamster diaphragm strips ex vivo, Esau (1989) [

107] determined both hypoxia and hypercapnia reduced diaphragm contractility and slowed the muscle relaxation phase (T

R) of diaphragm contraction. By extension, this could be responsible for the delayed T

E. Similarly, Herve et al. (1988) [

127] found in rat diaphragm strips that increased workloads as well as ryanodine, an inducer of muscle fatigue, both delayed T

R. And when overloaded by ryanodine, contractility was markedly lowered, and a diaphragm

contracture developed (excitation). Nicotine exerts a similar effect in toxic doses [

20,

21]. Although not reproduced in vivo, intact diaphragms might also be prone to contracture when T

R becomes longer than T

E (causing spasms and cramps). This could occur in a fatigued diaphragm working under higher respiratory rates and ventilatory workloads (both common in illness), when it is unable to fully relax and return to its original resting position in time for the next breath. Literature evidence supporting this notion was limited; however,

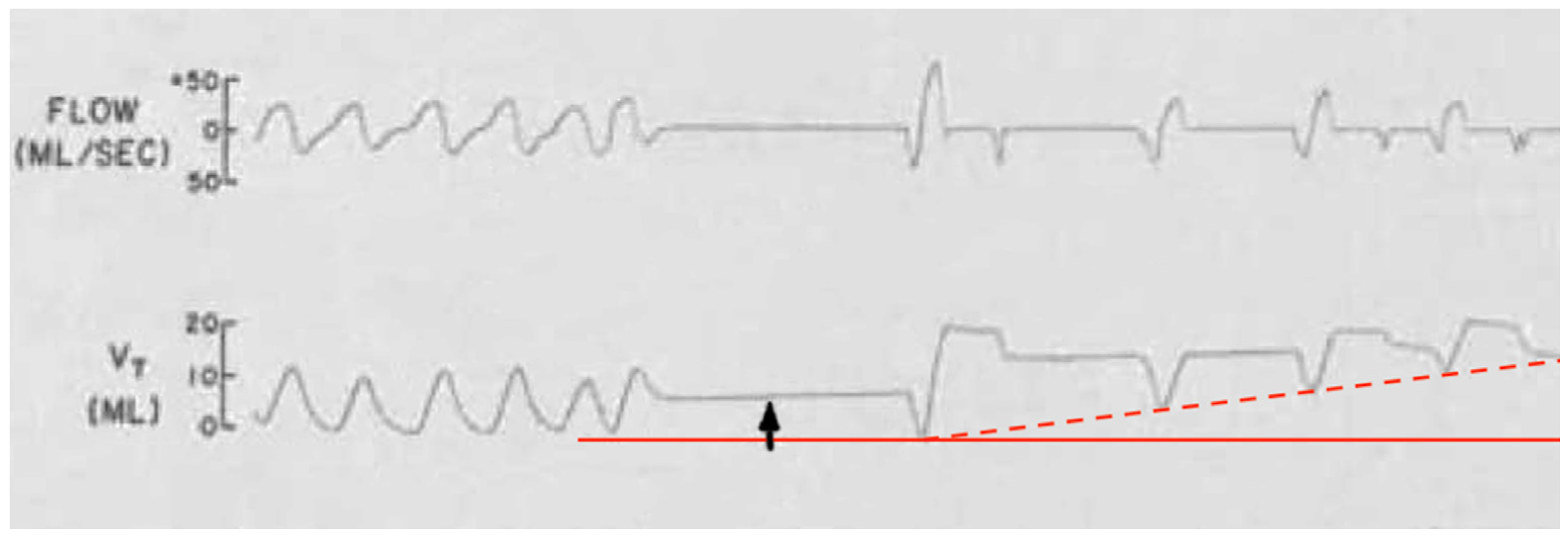

Figure 6 demonstrates an example. There is an upwards wander in the chest impedance (tidal volume, V

T) baseline with air trapping (hyperinflation). It occurred in a spontaneously breathing preterm infant immediately after a short apnea associated with silent squirming and a spike in surface EMG activity thought to be from abdominal contractions. Instead, diaphragm spasm could have been responsible. By comparison, air trapping in spontaneously breathing individuals does happen in COPD, asthma, and interstitial lung diseases; however, does not apply here given the patient’s age.

Along with hypoxia, hypercapnia, ryanodine, fatigue and possibly nicotine, both acidosis and endotoxins of

S. Pneumoniae and

E. Coli have been found to also prolong diaphragmatic T

R, precipitating diaphragm contracture ex vivo [

107] and further fatigue in vivo [

95]. This could be important not only in causing respiratory instability in infants with bacterial infections, but also sudden respiratory arrests in SIDS, SUDC and all other age groups. Both respiratory acidosis and metabolic acidosis (the latter for example from hypovolemia-shock as well as upper respiratory infections and diarrhea-associated bicarbonate loss) [

128] overlap with SIDS risk factors, including intercurrent infections, dehydration, fever and overheating. They could manifest in deadly fashion at the diaphragm by sudden respiratory failure from contracture. In fact, extreme acidosis and hyperkalemia at SIDS autopsies were reported in a 2006 online Medscape article but unfortunately were never confirmed [

43]. Electrolyte disorders can affect the diaphragm much in the same way as the examples above, by inducing fatigue, but in this case from excitation-contraction coupling dyshomeostasis. The author went on to mention how critical acidosis could have developed in the days preceding the deaths. Both disorders were also identified in a report of 20 infants with idiopathic postneonatal apnea occurring in association with hypomagnesemia [

129]. The sickest ones demonstrated bradycardia, acute respiratory distress and skeletal muscle hyperirritability; however, the diaphragm itself was not investigated. That author later went on to suggest hypomagnesemia causation in SIDS. Severe hypokalemia, too, is a known cause of respiratory muscle paralysis leading to asphyxiation [

44]. Finally, parenteral nutrition, commonly administered to undernourished neonates, carries a risk for metabolic acidosis [

130] and thus potential for fatigue-excitation. In summary, it appears hypoxia, hypercapnia, acute acidosis, endotoxins, nicotine and electrolyte disorders all intersect at the diaphragm in infants, altering breathing mechanics (reduced contractility and delayed relaxation), culminating in fatigue and excitation in the form of spasms and cramps with consequent apneas and other forms of respiratory instability, leading to HE.

Like the limbs, the diaphragm is composed of skeletal muscle. Fatigued skeletal muscles develop increased tonicity and neuromuscular excitation under increased workloads, commonly experienced when one is unfit, dehydrated or overheated [

84]. Examples of muscle excitation in vivo include twitches and fasciculations, spasms and cramps (sustained spasms), myoclonus (short arrhythmic spasms), and arrhythmias like flutter and fibrillation (which are well known to affect the heart). Pathological excitation of respiratory muscles has already been described, as evidenced by diaphragmatic and respiratory flutter. Importantly, whereas apnea from diaphragm spasm is not life-threatening because of its transience, that from a sustained cramp could be. With persistent diaphragm cramp-contracture in an infant, severe hypoxemia would ensue, causing sudden hypotonia, cyanosis and possibly seizure, followed by bradycardia and cardiac arrest and death if not rapidly aborted. Unlike the 7-year-old case patient who autoresuscitated by troubleshooting and learning to breathe

in reverse, infants are clearly not capable of such a complex, counterintuitive task, thus a cardiopulmonary emergency could arise. Finally, whereas limb muscle cramps can be aborted by active or passive stretching, this is not clearly possible with the internally located diaphragm. However, it is interesting to consider how the patient’s rescue breaths might have terminated his DCC. Perhaps the rapid combination of expiration and inspiration forced the diaphragm to initially recoil cranially and then quickly stretch as it moved caudally with inspiration, thereby overcoming the contracture tension and returning to normal function.

In infants with respiratory instability from diaphragm fatigue, diaphragmatic spasms with consequently delayed relaxation (akin to prolonged cardiac repolarization in diastole after premature ventricular contractions occur) are hereby proposed to cause the observed forced expirations and breath-holding pauses, respectively, along with hypopneas and prolonged apneas. Diaphragm spasms would mimic abdominal muscle contractions seen on surface EMG. They too could increase esophageal and gastric pressures (diaphragm moves cranially, thereby reducing thoracic volume). This is supported by the diaphragm/RAM-induced apneas of the Lopes study [

4] and provides an alternative explanation of HE, ridding any notion of a voluntary or behavioral component to forced expirations and breath-holding. It is also more intuitive given it is unlikely an undernourished, feeble preterm infant would be capable of persistently tensing their abdomen in one instance for over two minutes, to the point of dropping their oxygen saturations below 75% [

121]. Diaphragm spasms could also explain the silent nature of HE simply because an inspiration cannot be taken while the organ is inactivated. Furthermore, the pain of spasm would explain the grimacing, writhing, and kicking. Finally, this provides a solid foundation to hypothesize that persistent spasm, or diaphragm cramp-contracture, could be responsible for non-arrhythmogenic sudden unexpected deaths in infants (and possibly other ages too).

It follows then that periodic breathing also involves fatigue of the diaphragm that becomes temporarily dependent on the accessory muscles to maintain ventilation until reversed by rest (and vice versa by load sharing). Specifically, cyclical episodes of diaphragm fatigue, work overload and consequent spasms with transient inactivation followed by load compensation by RAM activation and then RAM fatigue and spasms would give rise to a repetitive sequence of hyperpneas (from diaphragm spasm), hypopneas with paradoxical breathing (by independent RAM contractions while the diaphragm is temporarily inactivated) and apneas (simultaneous failure of both diaphragm and RAM) commonly observed and as seen in

Figure 7 [

131]. Seppä-Moilanen (2019) [

132] determined periodic breathing was substantially reduced with supplemental oxygen and caffeine in 21 preterm infants. Apneas were also reduced in frequency. Both interventions may have improved diaphragm function directly rather than by centrally mediated effects. Aubier (1989) flatly summed this up, stating, “It is clear that the majority of chest physicians have emphasized disorders of the lung or abnormalities of ventilatory control while ignoring the muscles”.

2.5. Diaphragm Fatigue, Excitation and Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children and adults is a highly prevalent, frequently underdiagnosed condition. Sleep disorders are often missed by parents or the individual. OSA too carries significant short and long-term morbidity and mortality. Complications include systemic and pulmonary hypertension, cardiomyopathies, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, cardiac arrhythmias, stroke, venous thromboembolism, and increased risk for SCD [

133]. It is also associated with gastroesophageal reflux, which improves significantly with CPAP; however, the mechanism linking the two has remained unknown [

134]. Like HE above, but in older children and adults with OSA, transient diaphragm spasms and compensatory RAM action are hereby proposed to cause the observed apneas and hypopneas, respectively, as seen in

Figure 8.

This is not to dismiss the existence of upper airway (supraglottic) obstructions from atonic muscles or enlarged tonsils. In fact, they contribute to DD because of the increased work of breathing from added airway resistance. Furthermore, this novel diaphragmatic paradigm of OSA states that obstruction develops when RAM independently attempt to breathe against the immobilized diaphragm inactivated by spasm. This would explain the doubling of pulmonary resistance mentioned above, which was associated with HE in mechanically ventilated infants [

122]. It is also supported by Southall’s anecdotal findings of initial resistance to inflating the lungs when resuscitating those with severe HE, even with functioning tracheostomy or endotracheal tubes in situ (maintaining airway patency) [

35]. Additional support comes from Miller et al. (1993) [

135], who revealed in the breaths immediately preceding and following apneas in preterm infants, there was a stepwise increase in total pulmonary airway resistance not caused by supraglottic muscle collapse. Other evidence linking diaphragm involvement in OSA comes from an EMG study comparing activation of the respiratory muscles, including those of the upper airway, ICM and diaphragm, in adults with OSA with healthy controls [

87]. All such respiratory muscles in the test subjects were more active than controls, both awake and asleep, reflecting an added workload. Moreover, with the onset of airway obstruction, there was a breath-to-breath, rapid drop in D-EMG followed by a gradual, then sudden increase with resumption of airflow a few seconds later. This was mirrored by similar changes in transdiaphragmatic pressures. The reduction was thought to be from reduced neural drive and an inhibitory reflex but could rather have been from diaphragm fatigue and spasm. It appears once the diaphragm had recovered from spasm it was able to resume functioning; however, a higher level of work was needed initially, probably to overcome airway resistance by diaphragm hypercontraction and immobility as well as the resistive elastic forces of pulmonary compliance.

It follows then from chest impedance studies in OSA, that when RAM function independently of a diaphragm inactivated by spasm, low-amplitude hypopnea waveforms are produced. These would mimic obstructive apneas (

Figure 8B) and, at bedside, might appear with rib retractions and paradoxic breathing (thoraco-abdominal asynchrony). By contrast, when both diaphragm and RAM are simultaneously inactivated (e.g., by diaphragm spasm from REM sleep RAM inactivation, or “co-spasms” akin to respiratory flutter), near-flatline apneas appear, mimicking central apneas (

Figure 8A,C). Once spasms finally resolve, ventilations would resume (but initially at higher intensity). Indeed, upon careful scrutiny of impedance, flow and D-EMG waveforms in central apneas, most often seen is a fine, tremulous baseline. This could represent highly attenuated diaphragm electrical activity by pathological excitation. In fact, many central apneas in one D-EMG study were determined to be from another cause [

88].

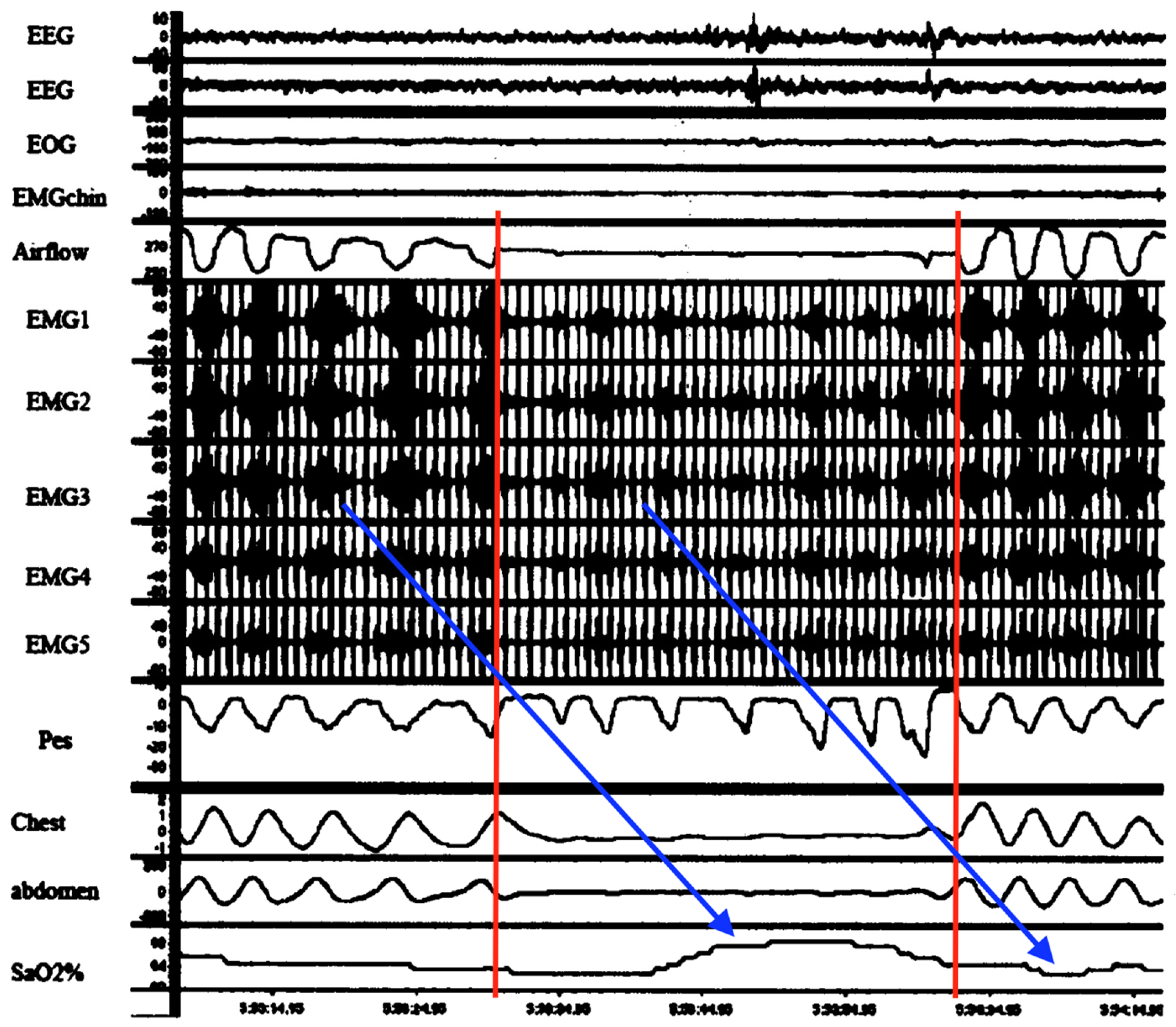

Figure 9 is very important because it temporally connects abnormal diaphragmatic electrical activity on intra-esophageal D-EMG in an adult apnea with a complete lack of ventilatory movements. It was neither a classic central, obstructive nor even mixed apnea. Although cause and effect cannot be ascertained, there was significant attenuation of D-EMG amplitude (and frequency) during the episode. Combined with the lack of respiratory movements, this is consistent with diaphragm inactivation due to spasm (electromechanical dissociation). Respirations resumed but only with higher intensity electrical bursts (perhaps from increased neural drive and higher diaphragm work to overcome post-obstruction airway resistance). Also, although truncated, D-EMG and oxygen saturations exhibited periodicity, suggestive of respiratory load cycling with RAM. Lastly, this evidence suggests that D-EMG activity reflects not just neural drive, but rather a composite influenced by diaphragm electromechanical output.

A final (and rare) piece of evidence linking diaphragm hyperexcitation with abnormal breathing was found in a case report of three tetraplegic patients with generalized body spasms triggered by deep breaths or sudden body movements (both increase ventilatory workload) [

51]. Using esophageal D-EMG,

Figure 10 demonstrates the electrical waveform of a diaphragm spasm with a prolonged apnea. Apnea duration was longer than the spasm, supporting the notion of continued diaphragm inactivity by delayed relaxation (or resetting). Interestingly, symptoms occurred more often in colder environments and if anxiety was present (the former a SIDS risk factor, while the latter a known trigger of DHD and HE).

Nocturnal sweating is another known SIDS risk factor and hypothesized here to be secondary to overheating from increased diaphragm work, exacerbated by fevers and overwrapping in bed. In an Icelandic study of adults with OSA, frequent night sweats (≥3 times/week) were reported by 30.6% of male and 33.3% of female patients, compared with 9.3% of men and 12.4% of women in the general population (

p < 0.001) [

136]. Boys are also more likely to have night sweats than girls [

83], potentially reflecting an increased work of breathing. Evidence to support harder working, fatigue-prone respiratory muscles in boys compared to girls includes (1) significantly thinner diaphragms on ultrasound in preterm [

97] and adult males [

77], (2) a faster rate of diaphragm fatigue along with lower inspiratory endurance times based on transdiaphragmatic pressures in adult males [

78], and (3) higher overall respiratory morbidity and mortality in preterm males [

79]. Additionally, women demonstrated greater recruitment of ICM compared to men due to anatomic rib differences, thus reducing diaphragmatic workload [

80]. Lastly, male neonate mice exposed to in utero asphyxia for 7.5 min had decreased survival at one hour after birth compared to females (survival rates 52% and 69%, respectively) [

55]. Their diaphragms demonstrated significantly worse structural and functional deficits (reduced maximum tetanic force and fatigue resistance), persisting long-term in those that survived, but associated with higher morbidity and mortality. All these findings provide a compelling explanation for the male preponderance of SIDS cases.

Another important point about night sweats is the potential perils of polar fleece and other synthetic fabrics commonly used in children’s bedding and clothing. Essentially, these do not breathe (ventilate heat or wick body moisture) like natural fabrics do [

137]. Overheating might result, leading to increased risk of SIDS and SUDC, especially if febrile and over bundled. This could reduce the DCC threshold by increasing diaphragm fatigue or workload.

2.6. Peripheral Respiratory Failure in Septic and Cardiogenic Shock

Diaphragm muscle fatigue and failure have been reported in septic Mongrel dogs. In ten spontaneously breathing anesthetized animals given intravenous

E. coli endotoxin, all died within 4.5 h by respiratory arrest. Hussain et al. (1985) [

74] determined by transdiaphragmatic pressures and EMG of diaphragm and ICM that all cardiac arrests were preceded by rapidly progressive diaphragm muscle fatigue and sudden failure. This refuted traditional thought, that CNS depression coupled with severe lung disease was the cause of alveolar hypoventilation, severe hypoxemia, and death. Unfortunately, such techniques could not reveal if diaphragm excitation had occurred. However, the authors mentioned how diaphragmatic failure was not unique to sepsis, as it had also occurred in animals with cardiogenic shock induced by cardiac tamponade. That was in reference to Aubier et al. (1981) [

138], who had injected saline into the pericardial cavities of 13 spontaneously breathing adult dogs compared to seven on MV. Like severe sepsis, deaths occurred quickly, within 2.5 h, in all those of the former group secondary to progressive diaphragm fatigue and sudden failure. Electromechanical dissociation had occurred whereby neural drive was maintained to the diaphragm (as measured by phrenic nerve root electrodes), but the respiratory muscles failed as force generators. Three possible causes were outlined: (1) blockage of nerve impulses at the neuromuscular junction; (2) impairment of excitation–contraction coupling; and/or (3) failure of the contractile machinery itself. The latter was reasoned most likely, in keeping with putative DCC, and probably had occurred from the effects of diaphragmatic hypoperfusion in shock. This would have led to local hypoxemia and a shift to anerobic metabolism within the diaphragm along with lactic acid accumulation contributing to the contractile dysfunction and organ failure. By extension, under high respiratory rates, when there is less time for diaphragm perfusion to occur, local hypoxia and acidosis would be exacerbated [

139]. This fatigue–failure process in hypoperfusion is supported by a study in which diaphragm perfusion pressures were directly increased via phrenic artery catheters after diaphragm fatigue was induced in anesthetized, ventilated dogs [

140]. It reversed the DD.

A pattern emerges from the above two circulatory shock experiments (septic and cardiogenic), wherein peripheral respiratory fatigue and failure preceded cardiac arrests and rapid deaths in previously healthy, spontaneously breathing animals. Hypotension with reduced diaphragmatic perfusion appears to be the common pathologic mechanism wherein blood supply did not meet the metabolic demands of the organ. Anemia (already discussed) and hemorrhagic shock [

114] would worsen this, as would deficiencies of oxygen and substrates like glucose, fatty acids, and electrolytes such as potassium, calcium, phosphorous, and magnesium, which are important in excitation–contraction coupling. Indeed, acute hypophosphatemia has been linked to respiratory fatigue in hospitalized patients [

141] and associated with prolonged MV and delayed discharge from the pediatric ICU [

142]. More than one author has suggested this in SIDS causation, where hypomagnesemia too has been suspected in causing severe limb muscle weakness worsened by prone position (asphyxia hypothesized from inability turning head to avoid rebreathing) [

41]. However, we now have a stronger mechanism that links all such electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities, and it centers on sudden diaphragmatic failure.

As such, in a young infant sleeping at home with dehydration, acute electrolyte disorders, and acidosis from both metabolic and respiratory causes, as well as perhaps diaphragm viral myositis (vide infra)—all compounding hypoxemia and hypercapnia worsened by diaphragm fatigue—it could be as simple as an acute workload increase by REM sleep or a roll to the prone position that suddenly triggers excitation by DCC. Acute bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis and respiratory failure would ensue, followed by RAM activation (if arousal occurs) and a terminal struggle to breathe against the internal airway obstruction produced by the hypercontracted diaphragm. Within only 1–2 min, critical hypoxemia, bradycardia, cardiac arrest, and death would occur. All the while happening silently and without warning, unwitnessed, and with rapid deterioration ultimately leading to a postmortem SIDS diagnosis.

Table 3 describes such a sequence of diaphragm fatigue-DCC-respiratory arrest in a hypothetical infant sleeping upstairs in a smoking household in a cold winter climate with artificial home heating.

2.7. Diaphragm and Limb Myopathy, Contraction Band Necrosis and Tardieu Spots

It is proposed that respiratory arrest by DCC is responsible for some SIDS and SUDC cases as well as some SCD in adults. Like the novel obstruction of OSA outlined above, where diaphragm spasm mechanically resists RAM contractions (causing transient apneas-hypopneas), sustained apneas would occur in DCC. If not overcome by autoresuscitation or rescue breaths, asphyxia and death will ensue. Unfortunately, like ventricular fibrillation, pathological pump contractions are temporary and do not persist postmortem, making it impossible to confirm at autopsy. However, Kariks (1989) [

143] found indirect evidence in the diaphragms of SIDS victims. Although controls were not provided, contraction band necrosis was present in 82% of diaphragms (D-CBN) along with focal-to-diffuse myofiber ruptures (sarcomere disruptions) and fibrous scars. Acute inflammatory cell infiltrates were not seen (suggesting a hyperacute process). Tissue staining revealed that some sort of diaphragmatic hypercontraction injury (causing irreversible sarcomeric spasm) had occurred terminally and acutely under prolonged anoxia, leading to contracted segments of thick and thin muscle filaments. Fibrous scars in various stages of healing suggested prior non-fatal injuries had occurred by repeated HE in the preceding days to weeks. Silver & Smith (1992) [

144] confirmed these myopathic findings, stating D-CBN was common in 125 neonates and infants that had died suddenly, primarily by asphyxia. This included birth asphyxia, drownings, suffocation, severe burns with carbon monoxide poisoning and SIDS. Other modes of death included meningitis, head injuries and acute dehydration from severe gastroenteritis [

86]. They remarked, “The morphologic age and, if present, stage of healing in each case suggested that the diaphragmatic lesion commenced at or shortly before death or at the time of the cardiac arrest that led to death”. Despite such compelling results, and a few other reports, research in this promising area stalled. Regardless, the evidence makes it imperative to start including diaphragm histology in all autopsies involving sudden unexpected deaths.

A clue to the origin of the diaphragm myopathy in SIDS comes from a study involving acute loading of rabbit inspiratory muscles well above their fatigue thresholds [

145]. In other words, extreme exercise. Along with significant hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis (both suggesting diaphragm insufficiency), post-euthanasia sarcomere disruptions with significantly inflamed and necrotic diaphragm tissues was demonstrated in all test animals. Moreover, this occurred in a load-dependent manner (i.e., higher ventilatory workloads correlated to larger areas of myopathy). There was no mention of D-CBN, however, none of the rabbits had died during testing (i.e., presumably no DCC). Interestingly, only 1% of the diaphragm surface area fraction was abnormal, occurring most often in the costal diaphragm and less so in the crural portion and parasternal intercostals. Injured fibers were more widespread throughout the diaphragm in some animals, whereas localized in others. Similar findings were disclosed in 18 preoperative COPD patients exposed to short inspiratory overloads compared to 11 preoperative controls with normal pulmonary function [

146]. Intraoperative diaphragm biopsies revealed sarcomere disruptions in all, which were significantly pronounced in the case patients (higher area fractions and densities). Necrosis and inflammatory cells were not observed, possibly due to shorter duration, less intense resistive loading.

In summary, excessive ventilatory workloads exerted load-dependent myopathic changes in the inspiratory muscles of test animals and humans similar to those identified in SIDS. Although little more was found in the literature on the mechanism of D-CBN—and despite no comparative evidence demonstrating muscle cramps as a cause of sarcomere disruption, inflammation or contraction bands in the limbs—progressive diaphragm fatigue culminating in critical excitation is a legitimate CBN candidate. In other words, DCC could be the hypercontraction injury seen in SIDS (and other sudden unexpected deaths). Simultaneous viral infections appear to contribute to the myopathy.

Similar histopathologic changes were reported in children with incapacitating leg cramps associated with viral influenza, predominantly serotype B. Conducted by retrospective analyses of hospital cases of influenza-associated myositis (IAM) as well as case reports and reviews articles, Agyeman et al. (2004) [

147] found that calf muscles alone or together with other limb muscle groups (undisclosed types) were involved in 69% and 31% of a combined 316 cases, respectively. There was a gender ratio of 2:1, male–female, in these school-aged children of median 8.5 years of age (range 2.5–14). Serum creatine phosphokinase (CPK, or creatine kinase, CK) levels were massively elevated along with lactic dehydrogenase and aspartate transaminase. Skeletal muscle troponin-I (STnI) is even more sensitive and specific [

148]. Ten children (3%) developed severe rhabdomyolysis, eight had acute renal failure, two required MV, and another one died. The authors referenced other calf muscle biopsy reports in pediatric IAM, demonstrating patchy necrosis with scant inflammatory infiltration in 11 of 12 in one series and 28 of 35 with muscle degeneration, necrosis, and scant infiltrates in another. Because of the lack of infiltration, the authors used the term myopathy in lieu of myositis. All such findings are important because the diaphragm too could be vulnerable to “direct muscle invasion by virus particles or immune-mediated muscle damage.” This could have been responsible for the two cases requiring MV and the one who died. Cell injury along with inflammatory mediators might have contributed to progressive diaphragm fatigue, excitation, and ultimate respiratory failure. Indeed, Eisenhut (2011) [

90] reported marked diaphragmatic abnormalities in a 5-month-old girl admitted with RSV bronchiolitis and poor feeding who succumbed in hospital to a sudden, unexpected death. Although grossly normal, diaphragm histology revealed myofiber destruction, focal segmental myocyte necrosis, myocyte regeneration, and focal infiltrates of macrophages and small lymphocytes. Interestingly, similar findings were reported in COVID-19 deaths in adults [

47,

149]. Such changes provide even more support to evaluate diaphragm histology in sudden death cases involving viral (or bacterial) infection. Moving forward, serum CK, CK-MM (skeletal muscle isoenzyme) or sTnI levels and venous blood gases could screen for and risk-stratify those at risk for respiratory decompensation by critical diaphragm fatigue and excitation.

High CPK levels were also reported in malignant hyperthermia, where there is limb muscle rigidity, spasms, rhabdomyolysis, and myonecrosis caused by various anesthetics. Like Kariks’ diaphragm study, limb histology revealed CBN, segmental necrosis and degenerating muscle fibers caused by “prolonged hypercontraction” [

28]. Perhaps by extension, then, some of the deaths in this high mortality condition are caused by respiratory myopathy and Type II failure by DCC. Although no autopsy reports were available examining diaphragm histology in malignant hyperthermia, preceding DD is supported by the author’s mention of “unexplained persistent rises in end-tidal CO

2 levels”.

Another important finding at autopsy in SIDS and SUDC are intrathoracic Tardieu spots. These are petechial hemorrhages found on the linings of thoracic organs exposed to terminally negative air pressures, such as the epicardium, pleurae, and intrathoracic thymus (

Figure 11) [

150]. They are present in roughly 80% of SIDS [

151] and 50% of SUDC [

152] (as well as 30% SUDEP [

153]), also seen in septicemia, barotrauma, heat stroke, severe burn injuries, and some electrocutions [

154]. Like the Poets study [

3], they are thought to occur by agonal breathing against airway obstruction. Again, the cause has never been elucidated, only speculated to be laryngospasm or bronchospasm. The novel airway obstruction of DCC, however, could be it. This also provides a uniting terminal mechanism among the various causes of Tardieu petechiae.

Beckwith’s 1988 paper on Tardieu spots provides an excellent account on their pathogenesis [

155]. Two things require mention: (1) vigorous respiratory efforts are required to produce them, and (2) they developed when airway obstruction was induced experimentally at end-expiration and not any other phase of the respiratory cycle. Again, this is consistent with the case patient’s observation of bearhug apnea always being triggered at end-expiration. Perhaps maximal negative intrathoracic pressures are generated then, when DCC obstruction strikes, and tidal volume is fully expelled, thus giving a mechanical advantage to produce the hemorrhages. Moreover, it is just after this phase of the respiratory cycle when diaphragm contractions are first initiated (by neural stimulation). Like limb muscles, this is precisely when cramps are initiated—that is, upon their initial shortening [

156]. Future studies to reproduce Tardieu spots might be accomplished by inducing diaphragmatic paralysis in anesthetized infant test animals with bilateral surgical phrenectomies.

A fascinating response arises as to the question of why our patient first experienced DCC at age 7 and not any sooner. The only thing that had changed in his young life was ceasing his lifelong history of nocturnal thumb-sucking. Surprisingly, a literature review revealed several papers, including systematic reviews, supporting the role of pacifiers (dummies) as being SIDS-preventative [

118,

119]. Perhaps they reduce diaphragmatic workload or minimize ventilatory pausing at end-expiration (when the diaphragm relaxes maximally and about to contract for the next cycle), thus negating the opportunity for DCC to strike. Unfortunately, studies comparing respiratory waveforms both with- and without pacifiers could not be found. This too should be studied, by chest impedance, RIP, EMG and airflow monitoring using sleeping infants as their own controls.

Moving forward, experimentally confirming and reproducing all above pathological findings might be best accomplished by delivering percutaneous electrical currents to the diaphragms of anesthetized test animals. Even better, rebreathing nicotine and exhaled gases in dehydrated, septic, hyperthermic, and acidemic animals might accomplish it. In addition, it would be helpful to look for such changes in nicotine toxicity. This is important not only because of its extreme potency but also the ubiquity of nicotine vaporizer solutions worldwide and thus the cumulatively massive potential for serious harm by unintentional oral overdose, especially in children as they are more vulnerable. Treatment in such cases could start with preventing pathological excitation by reducing DD and workload.

2.8. Potential Complications of DCC—Speculation Alert!

A host of serious pathological consequences might stem from the unique combination of diaphragm anatomy, hypertonicity, and pathological excitation. Nowhere else does this appear in the body. Looking at

Figure 12, the musculotendinous diaphragm wraps around three tightly enveloped hiatuses, each providing passage of an important structure: the inferior vena cava (IVC), aorta, and esophagus.

Under increased diaphragmatic tone, spasms, cramps and other DHD, these structures could become squeezed and effectively clamped by the diaphragm itself. Duration and intensity of tone would dictate symptoms, also depending on the form of excitation: from transient in spasms to rhythmic in flutter and sustained in hypertonia and cramp-contracture. Elevated tonic electrical activity of the diaphragm (tonic Edi, i.e., “sustained diaphragm activation throughout expiration”) in 431 PICU patients was associated with the sickest ones in the acute phase of illness, and independently associated with bronchiolitis, tachypnea and hypoxemia [

157]. Affecting the youngest patients (0–12 months old versus 1–18 years) and occurring more often in those spontaneously breathing (versus MV), hypertonic Edi also predicted extubation failure. All suggests elevated tonic Edi could be a surrogate of diaphragm fatigue. Support for esophageal clamping is already provided by reports on diaphragm flutter in which a variety of gastrointestinal complaints were made, including hiccups, belching, retching, acid reflux, vomiting, and epigastric (or chest) pain (and visible pulsations) [

158]. Similarly, reflux occurs in OSA as mentioned above, and how it improved with CPAP [

134]. It could be caused by intermittent esophageal clamping and release from diaphragm spasms combined with negative intrathoracic pressures generated by breathing against the diaphragm. A reduced diaphragmatic workload with CPAP would explain the improvement. Alternatively, GERD in OSA could be secondary to esophageal sphincter weakness or increased gastric acid secretion with decreased salivation and swallowing during sleep. However, none of these would be expected to improve with CPAP. Notably, a medical history of reflux-aspiration is also common in sudden infant deaths [

2], supporting the notion of diaphragm hyperexcitation. Also, it is interesting to consider that acute anxiety might physically manifest at the diaphragm. It too could increase tone, leading to the commonly experienced gastrointestinal complaints that are nearly identical to those of diaphragm flutter. But what follows next is even more speculation on a host of potential complications from the hemodynamic-cardiopulmonary standpoint.

As opposed to the aorta, the IVC is thin-walled and under lower vascular pressures, thus more collapsible by clamping. Cardiac preload would drop, leading to reduced stroke volume and cardiac output. Along with aortic clamping and negative intrathoracic air pressure from breathing against obstruction, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PH) and raised hydrostatic pressures in the lungs would develop, resulting in pulmonary congestion and edema. With transient diaphragm spasms, these changes would be reversible, and the patient likely survives (consistent with a diagnosis of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema if substantial). However, with persistent clamping by DCC combined with agonal breathing, the PH and such findings would worsen (also forming Tardieu petechiae). Other associated pathologies from aortic clamping could include simultaneous acute left- and right-sided dilated cardiomyopathies (possibly Takotsubo cardiomyopathy), labile hypertension with hypertensive urgency/emergency and acute heart failure with increased risk of arrhythmias and sudden deaths. Severe hypotension (shock) below the diaphragm would lead to diaphragmatic hypoperfusion, leading to further hypoxemia and diaphragm excitation. This might explain the drastic desaturations observed in neonates with HE. It could also explain the increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis [

122]. Right-to-left cardiac shunting is possible too, perhaps through a patent foramen ovale or ductus arteriosus. This could explain paradoxic motion of the interventricular septum [

159] and valvulopathies seen in some patients with OSA [

160]. With IVC clamping, hemostasis of the venous circulation inferior to the diaphragm would occur, thereby contributing to venous thrombosis of the lower extremities with raised risk for thromboembolism (VTE) as well as pulmonary embolism and even stroke (paradoxical embolus through patent foramen ovale). Indeed, OSA has been identified as an independent risk factor for VTE (and stroke) [

161]. In that paper, the proposed mechanisms (pro-inflammatory state, intermittent hypoxia, and endothelial dysfunction) do not weigh up to the major mechanical hemodynamic changes of potential DHD.

Lastly, persistent esophageal clamping by agonal DCC would keep stomach contents held under pressure, only to be released and expelled postmortem from diaphragm relaxation. These would collect in the mouth and airways, commonly seen at autopsy in SIDS and other sudden unexpected deaths (e.g., SUDC, SUDEP, malignant hyperthermia) [

162]. Alternatively, these findings could be artifacts from passive movements by postmortem body handling (however, CPR was ruled out in an autopsy study [

163]).

Evidence supporting the above co-pathologies in DHD was scarce; however, some was provided by elevated pulmonary arterial pressures, as measured by echocardiography and right heart catheterization (gold standard). Transient PH was demonstrated in preterm infants with the onset of HE [

35]. It was also implicated in OSA in adults (particularly during REM sleep) [

164], SUDEP sheep models [

165] and most recently, Type II respiratory failure in an adult with congenital myopathy [

166]. In all such cases, PH was idiopathic. Autopsy evidence supporting putative DCC clamping of the IVC in SUDC included brain weights exceeding the 100th percentile in 53 of 56 cases, associated with cerebral edema and vascular congestion [

152].

2.10. Diaphragm Failure in Seizure Deaths (SUDEP)

There are several overlapping historical and autopsy findings among SIDS, SUDC and SUDEP, and this suggests a common pathological mechanism. We believe this to be DCC. SUDEP typically affects young adults who suddenly expire silently, unwitnessed at night, probably while sleeping, only to be found afterwards without overt signs of distress in prone bed position with aspirated gastric contents in mouth and airways. The lungs are very “wet” and heavy, engorged with blood and fluid. Tardieu spots are not uncommon (at least 30% of cases). These findings are in keeping with those of Zhang et al. (2022) [

153], who, using controls, determined at autopsy the primary mechanism of death in 13 SUDEP cases was asphyxiation (Tardieu spots, pulmonary congestion, and hemorrhages). Those in prone position were at significantly higher risk. Generally though, other than this, autopsies in SUDEP are considered “negative” (but yet again, diaphragm histology is not being done).

Zhang’s findings are supported by Ryvlin’s MORTEMUS study (2013) [

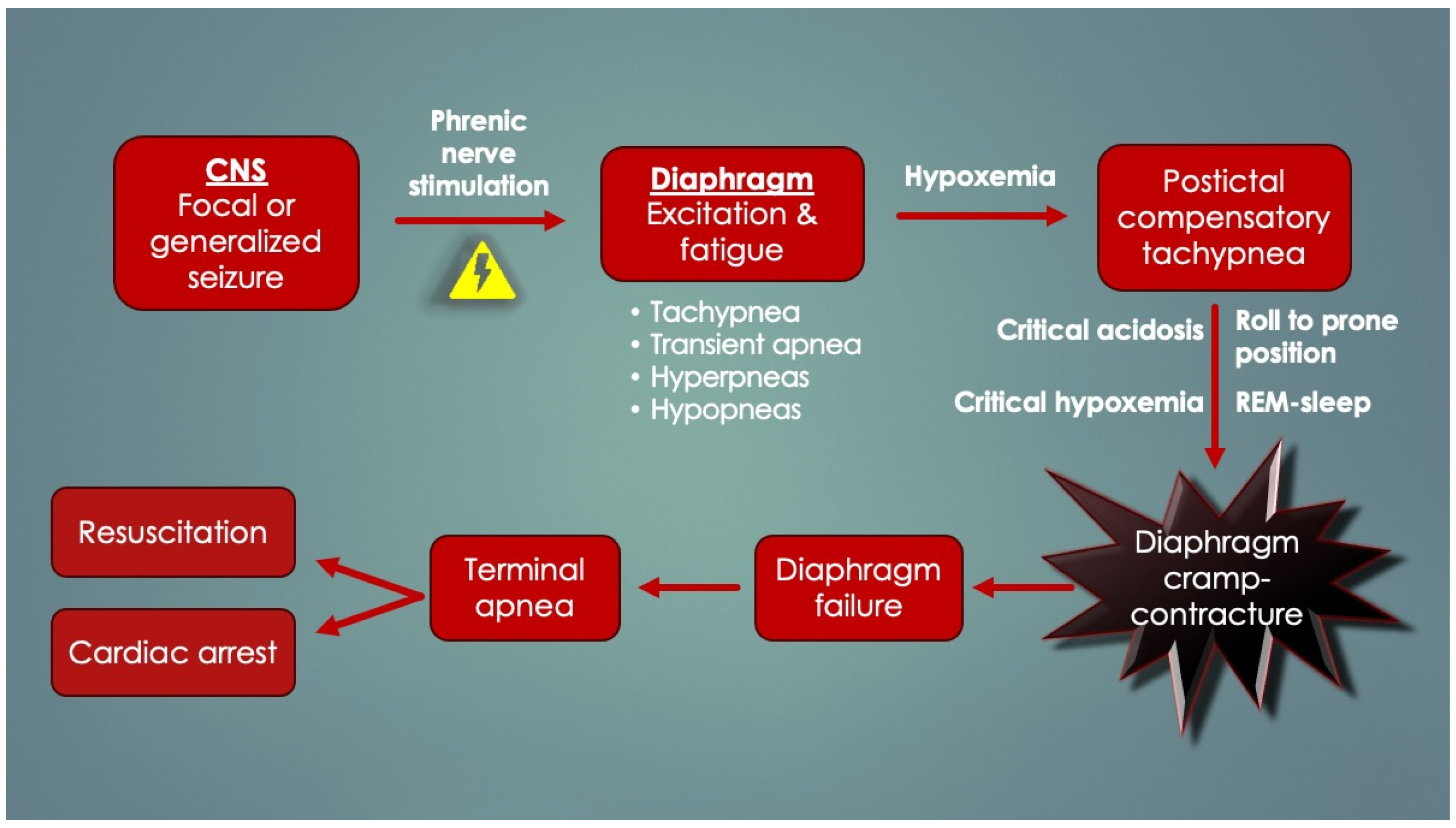

169], which elucidated terminal events in fatal seizures by retrospectively assessing patients who had continuous EEG, video and basic cardiorespiratory observations (respiratory movements) performed and recorded at epilepsy monitoring units. In ten confirmed SUDEP cases, postictal tachypnea occurred in all, followed by a terminal apnea and cardiac arrest either within three minutes or delayed by 11 min after temporary restoration of cardiorespiratory function. Over 90% had died in the prone position. This redirected attention from the heart to the respiratory system and CNS in SUDEP. Most of the seizures had started in the temporal lobe, a region involved in volitional breathing. Although the precise cause could not be elucidated (no airflow, chest impedance, oxygen saturations or end-tidal carbon dioxide levels), the terminal apnea was speculated to be centrally mediated by “post-generalized EEG suppression”. However, this is at odds with the asphyxia of the Zhang study and its autopsy findings. Instead, periictal diaphragm excitation and consequent fatigue could have occurred by

seizure transmission along the phrenic nerves. Seizure spread to a peripheral nerve (recurrent laryngeal), causing end-organ (laryngeal) spasm and respiratory arrest is not a unique idea, as it was performed experimentally in rats [

103]. Intracellular and systemic lactate, a byproduct of seizure causing metabolic acidosis, could have developed over time, thereby contributing to progressive lengthening of diaphragmatic T

R, worsened by the postictal (compensatory) tachypnea. This is consistent with the delayed aspect of some deaths. Postictal diaphragm fatigue exacerbated by prone positioning, REM sleep, progressive hypoxemia, and/or critical acidosis could have triggered terminal DCC-apnea. Given the silent internal struggle of the obstruction, this would not have easily been picked up by the cardiorespiratory observers. The general scheme for DCC in SUDEP is depicted in

Figure 14.

It is important for the DCC hypothesis to explain the rarity of deaths from SUDEP compared to the overall number of nonfatal seizures in the population.

Table 4 lists potential factors contributing to survival versus mortality in seizures from a hypothetical DCC standpoint. Important

fatality factors by immediate or postictal DCC include (1) hyperstimulation of the respiratory muscles (may not always be the case in seizures); (2) bilateral diaphragm hyperstimulation is followed by bilateral excitation in DCC, leading to complete bilateral diaphragm paralysis (some seizures are unilateral); (3) preexisting diaphragm fatigue, if it occurs, is worsened by the seizure (i.e., variable contributions by prone positioning, nicotine exposure, or intercurrent infections with dehydration and diaphragm myositis); and (4) sudden postictal RAM inactivation by REM sleep or excitation (RAM spasms or cramps).

Survival factors include (1) subcritical seizure duration (minimal postictal metabolic derangements like lactic acidosis and overheating), (2) subcritical hypoxemia (no cardiac arrest), and (3) postictal diaphragm spasms that are transient and recoverable but not persistent, like DCC.

Diaphragm involvement in fatal seizures is supported by a SUDEP mouse EMG study in which all deaths also occurred by terminal apnea. They carried mutations of a sodium ion channel protein (

Scn8a) identified in SUDEP victims. The channel is expressed in both sensory and motor neurons of the central and peripheral nervous systems. By inducing seizures while measuring D-EMG, Wenker et al. (2021) [

115] discovered terminal apneas occurred by continuous (tonic) diaphragm contractions. Deaths did not occur in those receiving MV. Perhaps it was life-sparing because of a reduced work of breathing (no DCC), or if excitation had occurred, MV overcame the airway resistance of diaphragm hypercontraction.

A final study supporting diaphragm excitation in seizure emerges from a study of 100 children under twelve years old with partial epilepsy using videotaped seizure analysis and data collection during the preictal, ictal, and postictal phases [

117]. Again, most of the 514 seizures were localized to the temporal lobe. The entire array of presentations in descending order of frequency included flushing, coughing, apnea*/bradypnea*, epigastric aura*, hyperventilation*, dyspnea*, hypersalivation, vomiting*/nausea, spitting, miosis, hiccups* and belching*. Although assumed secondary to autonomic causes, nearly all could have rather related to the diaphragm itself (marked by “*”). In other words, seizure activity could have been carried by the phrenic nerves, causing diaphragm excitation and fatigue, followed by spasms and gastroesophageal clamping. This is supported by a case report of a 6-year-old girl with daily hiccups associated with bilateral myoclonic D-EMG bursts following epileptiform EEG activity [

170]. Symptoms resolved with valproate. Epigastric, or visceral, aura is a symptom complex of short duration involving ictal abdominal discomfort, nausea and/or a burning sensation. It occurs most often with temporal lobe seizures and receives unusual descriptions such as “fluttering, pressure and rolling or turning of internal organs”. Again, this is consistent with putative diaphragmatic “butterflies” and other mild DHD symptoms. However, extreme fear and panic sometimes occur, and perhaps this is not without good reason. Sudden diaphragmatic inactivation by a focal seizure in a child, essentially a broken pump causing inability to breathe in the face of rapidly escalating hypoxemia and hypercapnia, would most certainly trigger severe apprehension, panic and an impending sense of doom. Interestingly, such symptoms also occur in abdominal winding injuries.