Superinfection of Rectovaginal Endometriosis: Case Report and Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Results

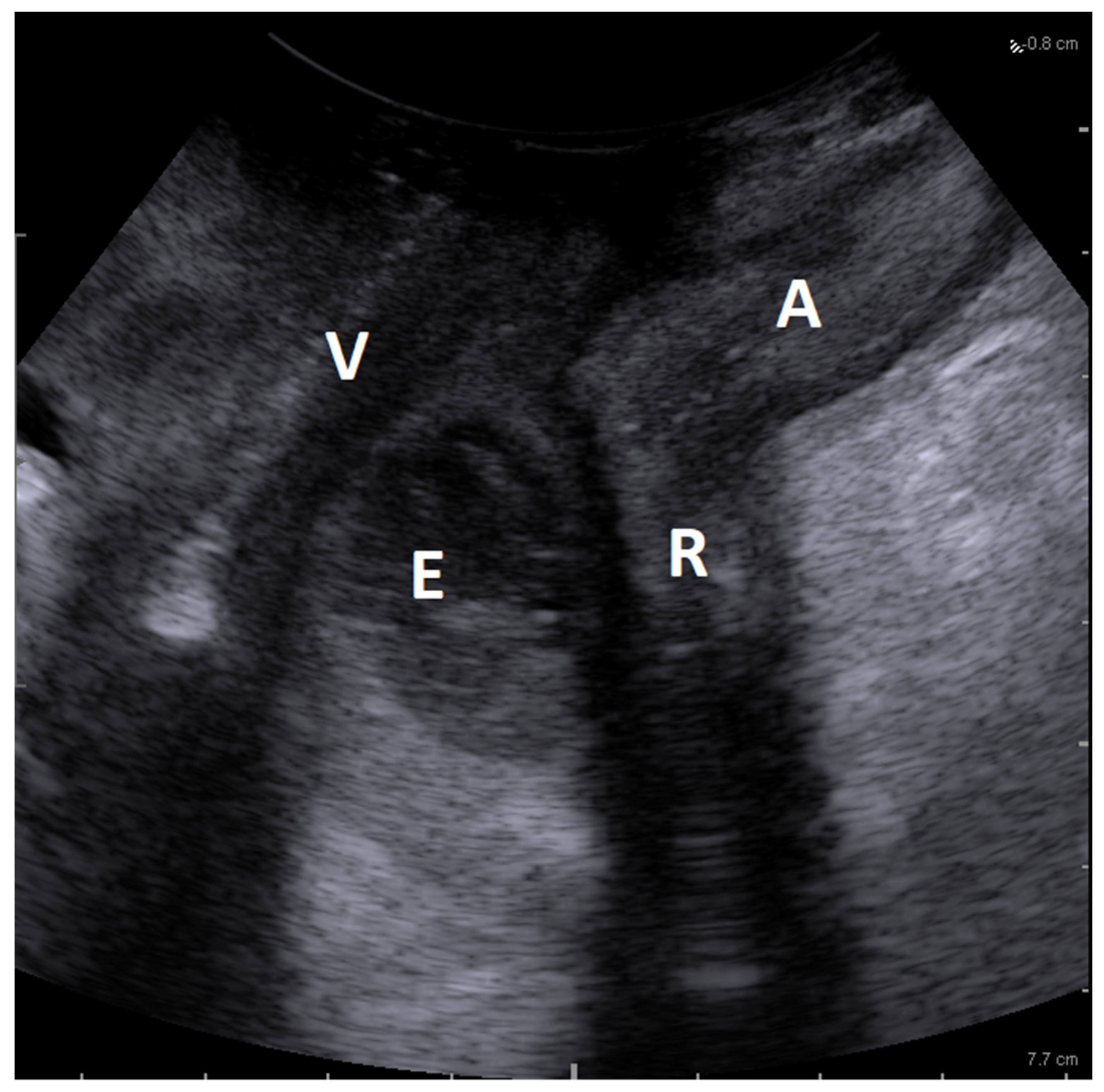

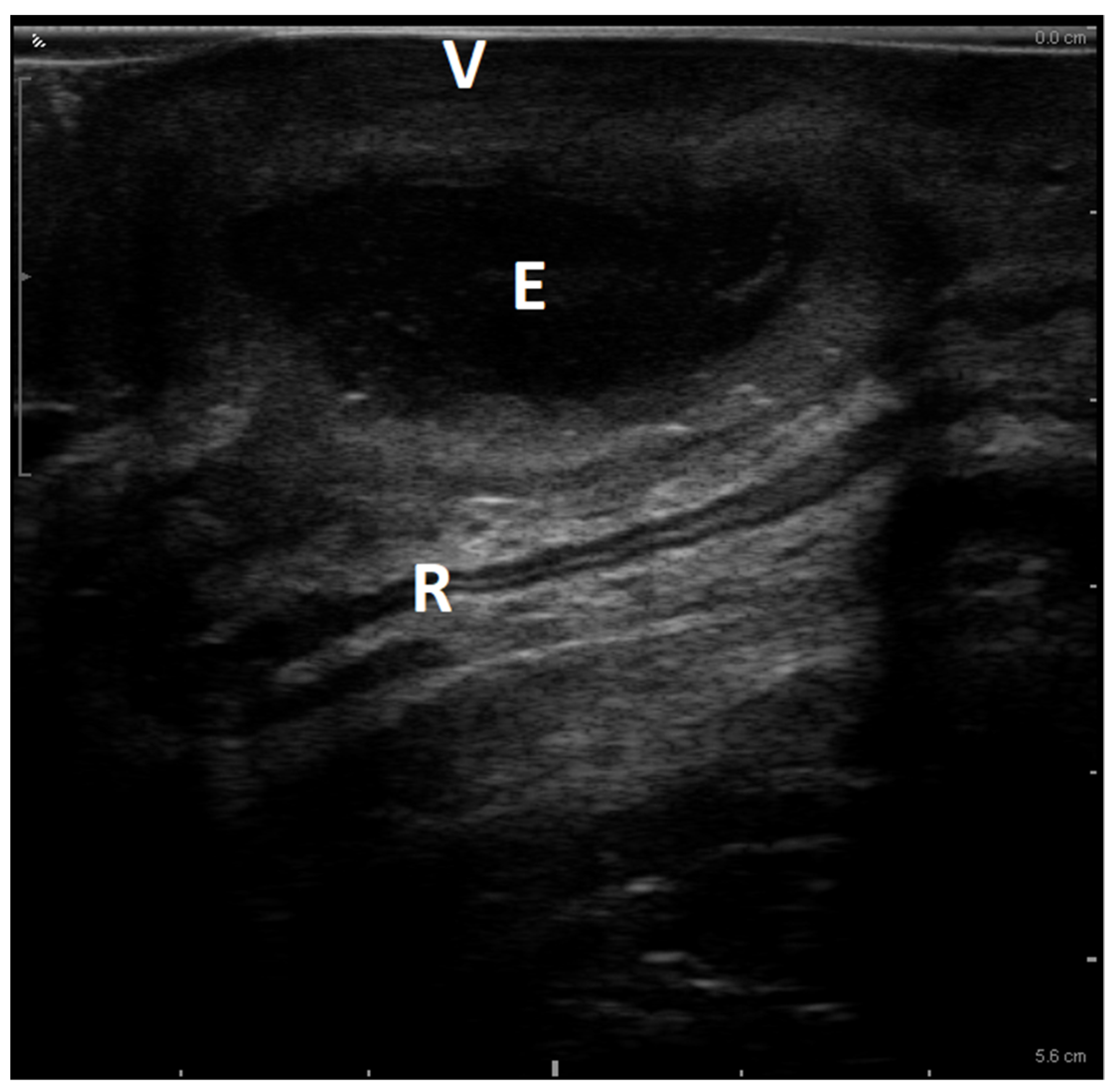

3.1. Case Report

3.2. Literature Review

4. Discussion

4.1. Presentation

4.2. Etiology

4.3. Imaging

5. Management

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bulun, S.E. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macer, M.L.; Taylor, H.S. Endometriosis and Infertility. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 39, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redwine, D.B. Diaphragmatic endometriosis: Diagnosis, surgical management, and long-term results of treatment. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 77, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubanyik, K.J.; Comite, F. Extrapelvic endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. N. Am. 1997, 24, 411–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.S.; Fritz, M.A.; Pal, L.; Seli, E. Speroff’s Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility, 9th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Giudice, L.C.; Kao, L.C. Endometriosis. Lancet 2004, 364, 1789–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, C.; Rotimi, O. Extragenital endometriosis—A clinicopathological review of a Glasgow hospital experience with case illustrations. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2004, 24, 804–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuohung, W.; Jones, G.L.; Vitonis, A.F.; Cramer, D.W.; Kennedy, S.H.; Thomas, D.; Hornstein, M.D. Characteristics of patients with endometriosis in the United States and the United Kingdom. Fertil. Steril. 2002, 78, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, J.W. Endometriosis in young teen-age girls. Pediatr. Ann. 1981, 10, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesel, L.; Sourouni, M. Diagnosis of endometriosis in the 21st century. Climacteric 2019, 22, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Viganò, P.; Somigliana, E.; Fedele, L. Endometriosis: Pathogenesis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdon, M.; Santulli, P.; Marcellin, L.; Maignien, C.; Maitrot-Mantelet, L.; Bordonne, C.; Bureau, G.P.; Chapron, C. Adenomyosis: An update regarding its diagnosis and clinical features. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soliman, A.M.; Surrey, E.; Bonafede, M.; Nelson, J.K.; Castelli-Haley, J. Real-World Evaluation of Direct and Indirect Economic Burden among Endometriosis Patients in the United States. Adv. Ther. 2018, 35, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Ussia, A.; Adamyan, L.; Wattiez, A.; Gomel, V.; Martin, D.C. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: The genetic/epigenetic theory. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 111, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, M.P.; Arcoverde, F.V.; Souza, C.C.; Fernandes, L.F.C.; Abrão, M.S.; Kho, R.M. Extrapelvic Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2019, 27, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeraswamy, A.; Lewis, M.; Mann, A.; Kotikela, S.; Hajhosseini, B.; Nezhat, C. Extragenital Endometriosis. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 53, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccaroni, M.; Bounous, V.E.; Clarizia, R.; Mautone, D.; Mabrouk, M. Recurrent endometriosis: A battle against an unknown enemy. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2019, 24, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, R.J.; Hickey, M.; Maouris, P.; Buckett, W. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008, CD004992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vercellini, P.; Somigliana, E.; Viganò, P.; De Matteis, S.; Barbara, G.; Fedele, L. Post-operative endometriosis recurrence: A plea for prevention based on pathogenetic, epidemiological and clinical evidence. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2010, 21, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, K.; Takamura, M.; Fujii, T.; Osuga, Y. Prevention of the recurrence of symptom and lesions after conservative surgery for endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, U.L.R.; Ferrero, S.; Mangili, G.; Bergamini, A.; Inversetti, A.; Giorgione, V.; Vigano, P.; Candiani, M. A systematic review on endometriosis during pregnancy: Diagnosis, misdiagnosis, complications and outcomes. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2015, 22, 70–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, T.; Ishi, K.; Takeuchi, H. A Study of Tubo-Ovarian and Ovarian Abscesses, with a Focus on Cases with Endometrioma. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 1997, 23, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.L.; Demopoulos, R.I.; Weiss, G. Infected Endometriotic Cysts: Clinical Characterization and Pathogenesis. Fertil. Steril. 1981, 36, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornman-Homonoff, J.; Fenster, T.B.; Schiffman, M.H. Percutaneous drainage of an infected endometrioma. Clin. Imaging 2019, 58, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manodoro, S.; Frigerio, M.; Barba, M.; Bosio, S.; de Vitis, L.A.; Marconi, A.M. Stem Cells in Clinical Trials for Pelvic Floor Disorders: A Systematic Literature Review. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 29, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barba, M.; Schivardi, G.; Manodoro, S.; Frigerio, M. Obstetric outcomes after uterus-sparing surgery for uterine prolapse: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 256, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, G.; Alfieri, N.; Tessitore, I.V.; Barba, M.; Manodoro, S.; Frigerio, M. Hematocolpos due to imperforate hymen: A case report and literature systematic review. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 34, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vitis, L.A.; Barba, M.; Lazzarin, S.; Molinari, S.; Spinelli, M.; Arosio, E.; Manodoro, S.; Frigerio, M. Female Genital Hair-Thread Tourniquet Syndrome: A Case Report and Literature Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2020, 34, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, M.; Bernasconi, D.P.; Manodoro, S.; Frigerio, M. Risk factors for obstetric anal sphincter injury recurrence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2021, 158, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, M.; Inzoli, A.; Barba, M. Pelvic organ prolapse and vaginal cancer: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 159, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, B.B.; Tuckson, W.B. Pelvic endometriosis presenting as a Supralevator abscess. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 1988, 80, 931–933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bulut, A.S.; Sipahi, T.U. Abscessed Uterine and Extrauterine Adenomyomas with Uterus-Like Features in a 56-Year-Old Woman. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 2013, 238156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, C.-H.; Kuo, H.-C.; Su, B. Endometriosis in a kidney with focal xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis and a perinephric abscess. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogan, E.; Okyay, E.; Saatli, B.; Olgan, S.; Sarioglu, S.; Koyuncuoglu, M. Tuba ovarian abscesses formation from decidualized ovarian endometrioma after appendiceal endometriosis presenting as acute appendicitis in pregnancy. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 2012, 10, 275–278. [Google Scholar]

- Erguvan, R.; Meydanli, M.M.; Alkan, A.; Edali, M.N.; Gökçe, H.; Kafkasli, A. Abscess in Adenomyosis Mimicking a Malignancy in a 54-Year-Old Woman. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 11, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, S.; Akira, S.; Kaseki, H.; Watanabe, K.; Ono, S.; Ichikawa, M.; Takeshita, T. A case of an abscessed cystic endometriotic lesion in the vesico-uterine pouch after oocyte retrieval. Gynecol. Minim. Invasive Ther. 2021, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Maeda, D.; Arimoto, T.; Kawana, K.; Fukayama, M.; Osuga, Y.; Fujii, T. Huge pyogenic cervical cyst with endometriosis, developing 13 years after myomectomy at the lower uterine segment: A case report. BMC Women’s Health 2014, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Kim, A.F.; Gardner, A.; Sun, K.; Brubaker, S. Peritoneovaginal Fistula and Appendicitis-Related Pelvic Abscess in Pregnancy. Am. J. Perinatol. Rep. 2020, 10, e129–e132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopha, S.C.; Rosado, F.G.N.; Smith, J.J.; Merchant, N.B.; Shi, C. Hepatic Uterus-Like Mass Misdiagnosed as Hepatic Abscess. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 23, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, F.; Wu, W. A Case of Psoas Muscle Endometriosis: A Distinct Approach to Diagnosis and Management. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2018, 25, 1305–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culley, L.; Law, C.; Hudson, N.; Denny, E.; Mitchell, H.; Baumgarten, M.; Raine-Fenning, N. The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: A critical narrative review. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2013, 19, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, C.; Minimo, C.; Margolin, G.; Orris, J. Appendiceal endometriosis presenting as acute appendicitis during pregnancy. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2007, 98, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauptmann, J.; Mechtersheimer, G.; Bläker, H.; Schaupp, W.; Otto, H.F. Deciduosis of the appendix. Differential diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Chirurg 2000, 71, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcourt, C.; Yombi, J.C.; Vo, B.; Yildiz, H. Salmonella enteritidis during pregnancy, a rare cause of septic abortion: Case report and review of the literature. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 39, 554–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scioscia, M.; Virgilio, B.A.; Laganà, A.S.; Bernardini, T.; Fattizzi, N.; Neri, M.; Guerriero, S. Differential Diagnosis of Endometriosis by Ultrasound: A Rising Challenge. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timor-Tritsch, I.; Lerner, J.P.; Monteagudo, A.; Murphy, K.; Heller, D. Transvaginal sonographic markers of tubal inflammatory disease. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1998, 12, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volontè, S.; Manodoro, S.; Frigerio, M. The Role of Ultrasounds for Anorectal Disorders. In Handbook of Pelvic Floor Ultrasound; Independently Published: Monza, Italy, 2022; ISBN 979-8352448557. [Google Scholar]

- Barba, M.; Frigerio, M.; Manodoro, S. Pelvic floor ultrasonography for the evaluation of the rectum-vaginal septum before and after prolapse native-tissue repair. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 72, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spelzini, F.; Cesana, M.C.; Verri, D.; Polizzi, S.; Frigerio, M.; Milani, R. Three-dimensional ultrasound assessment and middle term efficacy of a single-incision sling. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2013, 24, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manodoro, S.; Palmieri, S.; Cola, A.; Milani, R.; Frigerio, M. Novel sonographic method for the evaluation of the defects in the pubocervical fascia in patients with genital prolapse. Minerva Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 70, 642–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author and Ref. | Year and Country | Age and Previous Clinical History | Symptoms and Physical Examination | Instrumental Diagnostic | Diagnosis and Bacterium Detection | Management and Follow Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson [31] | 1988, USA | 32 yy, Several incisions and drainages of recurrent supraelevator abscesses | Lower quadrant abdominal pain. Tenderness of the abdomen in the tender lower quadrants. Hard, nontender, indurated mass at 8 cm on the posterior fourchette | X-ray and CT: distended bowel loops numerous large multicystic masses occupying the entire true pelvis | Pelvic endometriosis abscess. Detected Klebsiella species | LPT: Supracervical hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, sigmoid loop colostomy, and appendicectomy performed. The colostomy was closed two months after surgery. No recurrence (two years follow-up) |

| Bulut [32] | 2013, Turkey | 56 yy | Menorrhagia after three months of amenorrhea, pelvic and lumbar pain. Lobulated hard masses filling the pelvis up to the umbilicus | US: well-defined nodular masses around the uterus MRI: giant hypervascular lobulated mass of 8 × 12 × 13 cm, with central necrosis | Abscessed uterine mass and extrauterine adenomyomas with uterus-like features. Negative colture | LPT: total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with excision of intraligamentary bilateral leiomyoma-like masses and intraperitoneal adhesions. The postoperative period was uneventful |

| Cheng [33] | 2015, Taiwan | 53 yy, Acute pyelonephritis in the past | Intermittent recurrent right flank pain, mild fever for several years. Bilateral costovertebral angle tenderness | X-ray: bilateral renal stones. US: contracted right kidney. CT: kidney abscess with the invasion of psoas muscle. | Endometriosis in a kidney with xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis and a perinephric abscess. Detected Citrobacter koseri | CT: percutaneous drainage followed by right nephrectomy 3 days later. Asymptomatic at one month follow-up visit |

| Dogan [34] | 2012, Turkey | 30 yy | Fever, nausea, right lower quadrant pain at 24 weeks of pregnancy; left lower quadrant pain, high fever and vomiting at 28 weeks. Tenderness on abdominal examination and rebound tenderness at the right side of the uterus | At 24 weeks US: pericecal fluid At 28 weeks US: a 5 cm complicated left ovarian cystic mass compatible with tubo-ovarian abscess | At 24 weeks: endometriosis and deciduosis of appendix and acute appendicitis; at 28 weeks: infected endometrioma with deciduosis. Colture n/A. | At 24 weeks LPT: appendicectomy At 28 weeks LPT abscess was drained and left salpingectomy was performed. On postoperative day 5, the patient gave birth to a 1400 gr healthy male baby with spontaneous vaginal delivery. |

| Erguvan [35] | 2003, Turkey | 54 yy | Inguinal pain, night sweats, hot flashes. Irregularly enlarged uterus | Transvaginal US and MRI: 95 × 84 mm leiomyoma-like lesion. MRI: intramural uterine leiomyoma with cystic and necrotic degenerations | Histopathological diagnosis: abscess formation arising in a focus of adenomyosis. Colture n/A | Endometrial biopsy: inadequate. LPT to exclude malignancy: total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The postoperative period was uneventful |

| Matsuda [36] | 2021, Japan | 31 yy, Dysmenorrhea when she was 16 years old. Diagnosis of cystic lesion in the vescico-uterine pouch | Severe abdominal pain after oocyte retrieval. Before the oocyte retrieval: a goose-egg-sized anteverted and anteflexed uterus. Uterine mobility was low, and pain due to pressure on the uterus | Transvaginal US and MRI 4 cm cystic lesion low-absorbing similar to an abscess in the vescico-uterine pouch | Abscessed cystic endometriosis lesion in the vescico-uterine pouch. Detected Prevotella bivia. | Failure of conservative therapy, followed by LPS surgery: drainage of the abscess and ablation of the cystic lesion. She was discharged home on the same day. Embryo transfer was performed 3 months after surgery, resulting in pregnancy |

| Oda [37] | 2014, Japan | 41 yy, previous multiple myomectomy with opening of the anterior endocervical canal | Asymptomatic (she had undergone myomectomy of multiple uterine fibroids 13 years previously). Large cervical mass | Tranvaginal US: multilocular, hypoechoic lesions, with heterogeneous internal echogenicity. MRI: irregularly shaped cystic mass (overall diameter, >15 cm) in the upper anterior cervix | Histopathological diagnosis: Pyogenic cervical cyst exhibiting signs of endometriosis. Detected Escherichia Coli | LPT: total hysterectomy |

| Saleh [38] | 2020, USA | 36 yy | Lower abdominal pain, loss of appetite at 17 weeks of pregnancy. Tachycardia, spontaneous rupture of yellow purulent fluid from the posterior vaginal fornix, sepsis 24 h later | Transvaginal US: 5 × 2 cm multiloculated abscess in the posterior cul-de-sac MRI: right ovarian torsion versus abscess formation due to appendicitis | Histopathological diagnosis: abscess of endometriosis of the appendix with peritoneovaginal fistula. Colture n/A. | Failure of conservative therapy followed by LPS surgery (appendicectomy and toilette). Uncomplicated normal spontaneous vaginal delivery at 40 weeks |

| Sopha [39] | 2015, USA | 47 yy, Long history of diarrhea | Diarrhea, acute right upper quadrant and back pain with nausea and vomiting | CT: liver abscess | Histopathological diagnosis: Abscess of hepatic uterus-like mass. Detected Aeromonas sp, Entamoeba histolytica | Antibiotic therapy for two weeks followed by a CT-guided fine-needle aspiration and LPS surgery: segment VII excisional biopsy. Asymptomatic on follow-up evaluation |

| Zhao [40] | 2018, China | 28 yy | Eight-month history of lower abdominal and back pain and swelling | US: a cystic mass of 12 cm rising from the iliopsoas or left ureter. CT: suspect psoas abscess with left hydronephrosis MRI: A 10 cm mass near the left iliac vessel constraining the left ureter, left retroperitoneal endometriosis, adenomyosis | Histopathological diagnosis: psoas muscle endometriosis abscess. Colture n/A. | Left ureteral stenting and percutaneous drainage under local anesthesia, antibiotic administration. GnRH treatment for three months followed by LPS surgery: resection of the psoas muscle endometriosis. Asymptomatic at three-month follow-up. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barba, M.; Morciano, A.; Melocchi, T.; Cola, A.; Inzoli, A.; Passoni, P.; Frigerio, M. Superinfection of Rectovaginal Endometriosis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13091514

Barba M, Morciano A, Melocchi T, Cola A, Inzoli A, Passoni P, Frigerio M. Superinfection of Rectovaginal Endometriosis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Diagnostics. 2023; 13(9):1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13091514

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarba, Marta, Andrea Morciano, Tomaso Melocchi, Alice Cola, Alessandra Inzoli, Paolo Passoni, and Matteo Frigerio. 2023. "Superinfection of Rectovaginal Endometriosis: Case Report and Review of the Literature" Diagnostics 13, no. 9: 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13091514

APA StyleBarba, M., Morciano, A., Melocchi, T., Cola, A., Inzoli, A., Passoni, P., & Frigerio, M. (2023). Superinfection of Rectovaginal Endometriosis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Diagnostics, 13(9), 1514. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13091514