Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Past, Present and Future

Abstract

1. Introduction

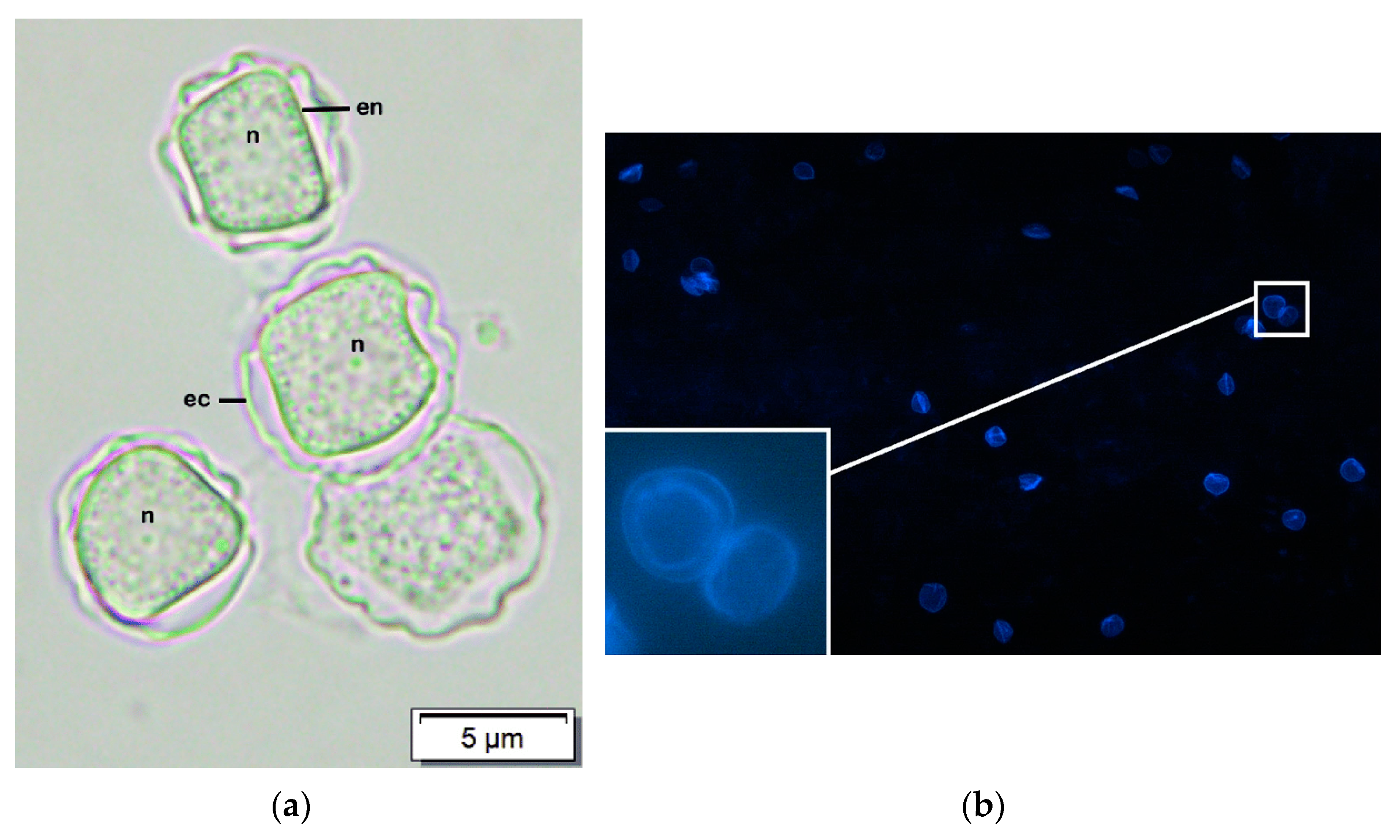

2. Culture and Microscopy

3. Corneal Biopsy

4. Polymerase Chain Reaction

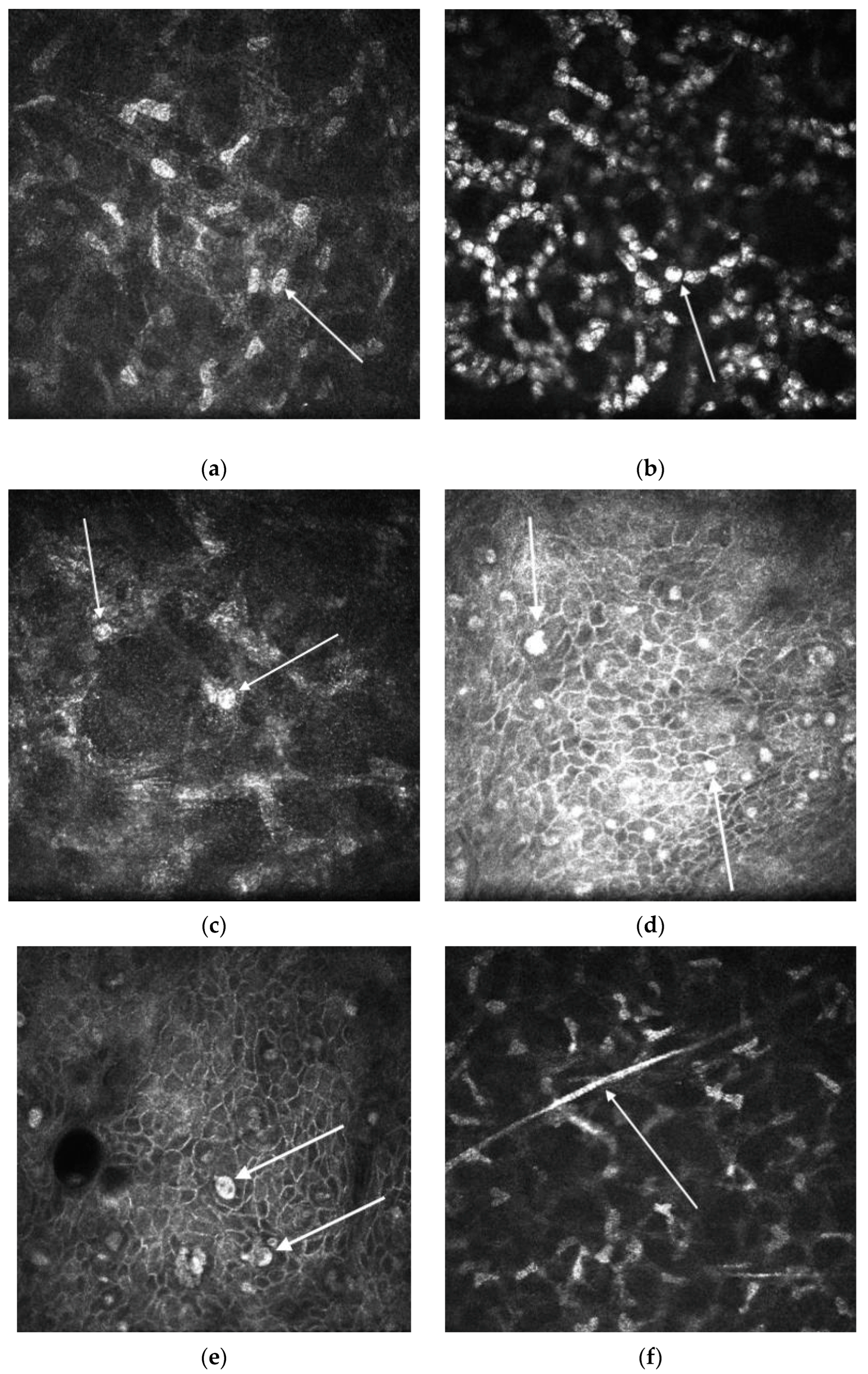

5. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy

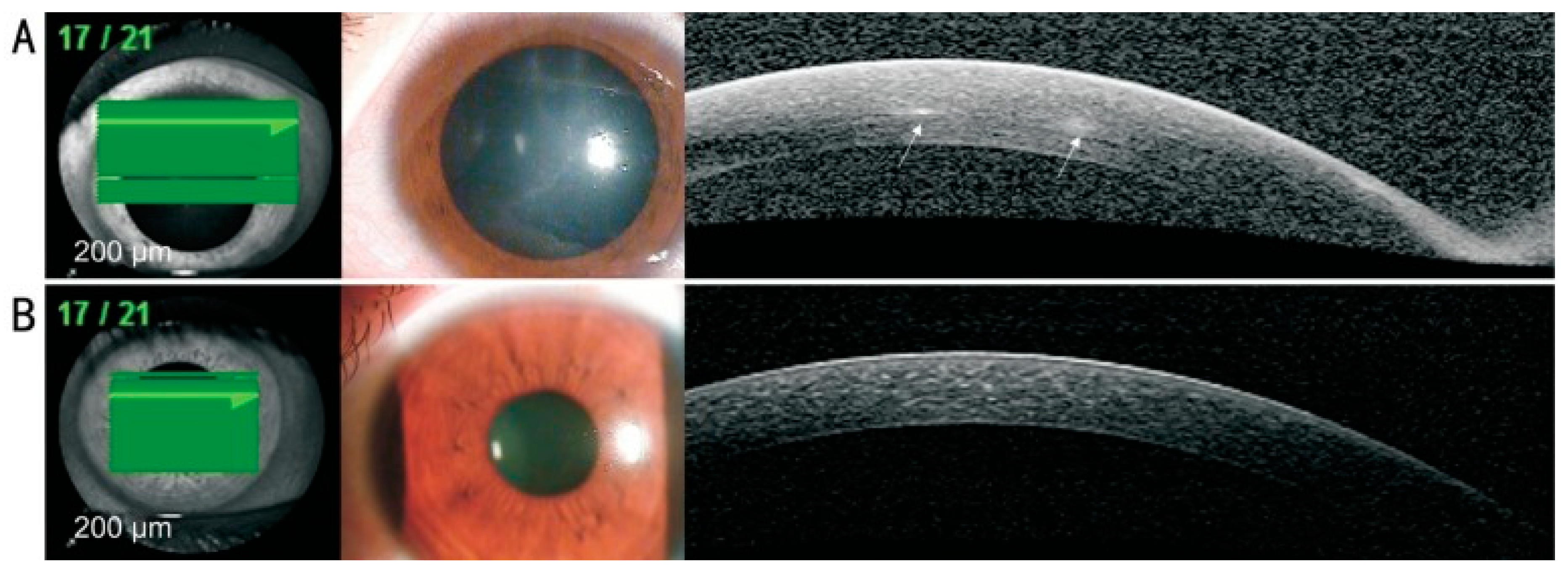

6. Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naginton, J.; Watson, P.G.; Playfair, T.J.; McGill, J.; Jones, B.R.; Steele, A.D. Amoebic infection of the eye. Lancet 1974, 2, 1537–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, F.; Lares, F.; Gallegos, E.; Ramirez, E.; Bonilla, P.; Calderon, A.; Martinez, J.J.; Rodriguez, S.; Alcocer, J. Pathogenic amoebae in natural thermal waters of three resorts of Hidalgo, Mexico. Environ. Res. 1989, 50, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, R.; Hauröder-Philippczyk, B.; Müller, K.-D.; Weishaar, I. Acanthamoeba from human nasal mucosa infected with an obligate intracellular parasite. Eur. J. Protistol. 1994, 30, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Tawfeek, G.M.; Bishara, S.A.; Sarhan, R.M.; ElShabrawi Taher, E.; ElSaady Khayyal, A. Genotypic, physiological, and biochemical characterization of potentially pathogenic Acanthamoeba isolated from the environment in Cairo, Egypt. Parasitol. Res. 2016, 115, 1871–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lass, A.; Guerrero, M.; Li, X.; Karanis, G.; Ma, L.; Karanis, P. Detection of Acanthamoeba spp. in water samples collected from natural water reservoirs, sewages, and pharmaceutical factory drains using LAMP and PCR in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 584–585, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnt, N.A.; Subedi, D.; Lim, A.W.; Lee, R.; Mistry, P.; Badenoch, P.R.; Kilvington, S.; Dutta, D. Prevalence and seasonal variation of Acanthamoeba in domestic tap water in greater Sydney, Australia. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2020, 103, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wopereis, D.B.; Bazzo, M.L.; de Macedo, J.P.; Casara, F.; Golfeto, L.; Venancio, E.; de Oliveira, J.G.; Rott, M.B.; Caumo, K.S. Free-living amoebae and their relationship to air quality in hospital environments: Characterization of Acanthamoeba spp. obtained from air-conditioning systems. Parasitology 2020, 147, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, F.; Lares, F.; Ramirez, E.; Bonilla, P.; Rodriguez, S.; Labastida, A.; Ortiz, R.; Hernandez, D. Pathogenic Acanthamoeba isolated during an atmospheric survey in Mexico City. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1991, 13 (Suppl. 5), S388–S389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pussard, M. Morphologie de la paroikystique et taxonomie du genre Acanthamoeba (Protozoa, Amoebida). Protistologica 1977, 13, 557–598. [Google Scholar]

- Gast, R.J.; Ledee, D.R.; Fuerst, P.A.; Byers, T.J. Subgenus systematics of Acanthamoeba: Four nuclear 18S rDNA sequence types. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 1996, 43, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, M.L.N.; Paes, J.; Rott, M.B. Genotype distribution of Acanthamoeba in keratitis: A systematic review. Parasitol. Res. 2021, 120, 3051–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsood, A.H.; Sissons, J.; Rezaian, M.; Nolder, D.; Warhurst, D.; Khan, N.A. Acanthamoeba genotype T4 from the UK and Iran and isolation of the T2 genotype from clinical isolates. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005, 54, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cave, D.; Monno, R.; Bottalico, P.; Guerriero, S.; D’Amelio, S.; D’Orazi, C.; Berrilli, F. Acanthamoeba T4 and T15 genotypes associated with keratitis infections in Italy. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2009, 28, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshni Prithiviraj, S.; Rajapandian, S.G.K.; Gnanam, H.; Gunasekaran, R.; Mariappan, P.; Sankalp Singh, S.; Prajna, L. Clinical presentations, genotypic diversity and phylogenetic analysis of Acanthamoeba species causing keratitis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Morales, J.; Morcillo-Laiz, R.; Martín-Navarro, C.M.; López-Vélez, R.; López-Arencibia, A.; Arnalich-Montiel, F.; Maciver, S.K.; Valladares, B.; Martínez-Carretero, E. Acanthamoeba keratitis due to genotype T11 in a rigid gas permeable contact lens wearer in Spain. Cont. Lens Anterior Eye 2011, 34, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuprasert, W.; Putaporntip, C.; Pariyakanok, L.; Jongwutiwes, S. Identification of a novel t17 genotype of acanthamoeba from environmental isolates and t10 genotype causing keratitis in Thailand. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 4636–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Ruiz, A.; Gonzalez-Zuñiga, L.D.; Rodriguez-Anaya, L.Z.; Lares-Jiménez, L.F.; Gonzalez-Galaviz, J.R.; Lares-Villa, F. Distribution and Current State of Molecular Genetic Characterization in Pathogenic Free-Living Amoebae. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Wei, Z.; Cao, K.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Q. The global epidemiology and clinical diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, D.S.J.; Deshmukh, R.; Ting, D.S.W.; Ang, M. Big data in corneal diseases and cataract: Current applications and future directions. Front. Big Data 2023, 6, 1017420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, D.S.J.; Ho, C.S.; Cairns, J.; Elsahn, A.; Al-Aqaba, M.; Boswell, T.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S. 12-year analysis of incidence, microbiological profiles and in vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of infectious keratitis: The Nottingham Infectious Keratitis Study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnt, N.; Hoffman, J.M.; Verma, S.; Hau, S.; Radford, C.F.; Minassian, D.C.; Dart, J.K.G. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Confirmation of the UK outbreak and a prospective case-control study identifying contributing risk factors. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 102, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, J.S.; Verani, J.; Heidman, N.; Hoppe-Bauer, J.; Alfonso, E.C.; Miller, D.; Jones, D.B.; Bruckner, D.; Langston, R.; Jeng, B.H.; et al. Acanthamoeba keratitis: The persistence of cases following a multistate outbreak. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012, 19, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verani, J.R.; Lorick, S.A.; Yoder, J.S.; Beach, M.J.; Braden, C.R.; Roberts, J.M.; Conover, C.S.; Chen, S.; McConnell, K.A.; Chang, D.C.; et al. National outbreak of Acanthamoeba keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solution, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1236–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höllhumer, R.; Keay, L.; Watson, S.L. Acanthamoeba keratitis in Australia: Demographics, associated factors, presentation and outcomes: A 15-year case review. Eye 2020, 34, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, S.E.; Ivarsen, A.; Hjortdal, J. Increasing incidence of Acanthamoeba keratitis in a large tertiary ophthalmology department from year 1994 to 2018. Acta Ophthalmol. 2020, 98, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randag, A.C.; van Rooij, J.; van Goor, A.T.; Verkerk, S.; Wisse, R.P.L.; Saelens, I.E.Y.; Stoutenbeek, R.; van Dooren, B.T.H.; Cheng, Y.Y.Y.; Eggink, C.A. The rising incidence of Acanthamoeba keratitis: A 7-year nationwide survey and clinical assessment of risk factors and functional outcomes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, D.; Koppen, C.; Van Looveren, J.; Meheus, A.; Tassignon, M.J. Contact lens-related corneal ulcers requiring hospitalization: A 7-year retrospective study in Belgium. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2006, 84, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKelvie, J.; Alshiakhi, M.; Ziaei, M.; Patel, D.V.; McGhee, C.N. The rising tide of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Auckland, New Zealand: A 7-year review of presentation, diagnosis and outcomes (2009–2016). Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2018, 46, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, J.Y.; Chan, F.M.; Beckingsale, P. Acanthamoeba keratitis cluster: An increase in Acanthamoeba keratitis in Australia. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009, 37, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thebpatiphat, N.; Hammersmith, K.M.; Rocha, F.N.; Rapuano, C.J.; Ayres, B.D.; Laibson, P.R.; Eagle, R.C., Jr.; Cohen, E.J. Acanthamoeba keratitis: A parasite on the rise. Cornea 2007, 26, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehr-Green, J.K.; Bailey, T.M.; Brandt, F.H.; Carr, J.H.; Bond, W.W.; Visvesvara, G.S. Acanthamoeba keratitis in soft contact lens wearers. A case-control study. Jama 1987, 258, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Illingworth, C.D.; Cook, S.D.; Karabatsas, C.H.; Easty, D.L. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Risk factors and outcome. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1995, 79, 1078–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, D.S.J.; Ho, C.S.; Deshmukh, R.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S. Infectious keratitis: An update on epidemiology, causative microorganisms, risk factors, and antimicrobial resistance. Eye 2021, 35, 1084–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robaei, D.; Carnt, N.; Minassian, D.C.; Dart, J.K. The impact of topical corticosteroid use before diagnosis on the outcome of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmus, K.R.; Jones, D.B.; Matoba, A.Y.; Hamill, M.B.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Weikert, M.P. Bilateral acanthamoeba keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 145, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.T.; Mondino, B.J.; Hoft, R.H.; Donzis, P.B.; Holland, G.N.; Farley, M.K.; Levenson, J.E. Successful medical management of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1990, 110, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, S.N., 3rd; Green, W.R.; Willaert, E.; Stevens, A.R.; Key, S.N., Jr. Keratitis due to Acanthamoeba castellani. A clinicopathologic case report. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1980, 98, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.J.; Parlato, C.J.; Arentsen, J.J.; Genvert, G.I.; Eagle, R.C., Jr.; Wieland, M.R.; Laibson, P.R. Medical and surgical treatment of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1987, 103, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auran, J.D.; Starr, M.B.; Jakobiec, F.A. Acanthamoeba keratitis. A review of the literature. Cornea 1987, 6, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dart, J.K.; Saw, V.P.; Kilvington, S. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Diagnosis and treatment update 2009. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 148, 487–499.e482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabin, G.; Taylor, H.; Snibson, G.; Murchison, A.; Gushchin, A.; Rogers, S. Atypical presentation of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea 2001, 20, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla Kent, S.; Robert, M.-C.; Tokarewicz, A.C.; Mather, R. Painless Acanthamoeba keratitis. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 47, 383–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illingworth, C.D.; Cook, S.D. Acanthamoeba keratitis. Surv. Ophthalmol. 1998, 42, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodall, K.; Brahma, A.; Ridgway, A. Acanthamoeba keratitis: Masquerading as adenoviral keratitis. Eye 1996, 10 Pt 5, 643–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, E.Y.; Joslin, C.E.; Sugar, J.; Shoff, M.E.; Booton, G.C. Prognostic factors affecting visual outcome in Acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology 2008, 115, 1998–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, D.N.; Awwad, S.T.; Petroll, W.M.; Bowman, R.W.; McCulley, J.P.; Cavanagh, H.D. Tandem scanning confocal corneal microscopy in the diagnosis of suspected acanthamoeba keratitis. Ophthalmology 2006, 113, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfawaz, A. Radial keratoneuritis as a presenting sign in acanthamoeba keratitis. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 18, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, F.C. A New Key to Freshwater and Soil Gymnamoebae: With Instructions for Culture; Freshwater Biological Association: Ambleside, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Feist, R.M.; Sugar, J.; Tessler, H. Radial keratoneuritis in Pseudomonas keratitis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1991, 109, 774–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, H.J.; Rao, N.A.; Lemp, M.A.; Visvesvara, G.S. Acanthamoeba keratitis successfully treated with penetrating keratoplasty: Suggested immunogenic mechanisms of action. Cornea 1984, 3, 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.F.; Matheson, M.; Dart, J.K.; Cree, I.A. Persistence of acanthamoeba antigen following acanthamoeba keratitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 85, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, G.A.; Gray, T.B.; Dart, J.K.; Pavesio, C.E.; Ficker, L.A.; Larkin, D.F.; Matheson, M.M. Acanthamoeba sclerokeratitis: Treatment with systemic immunosuppression. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 1178–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Srinivasan, M.; George, C. Acanthamoeba keratitis in non-contact lens wearers. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1990, 108, 676–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindquist, T.D.; Fritsche, T.R.; Grutzmacher, R.D. Scleral ectasia secondary to Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea 1990, 9, 74–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, A.S.; Dart, J.K.; Ficker, L.A.; Matheson, M.M.; Wright, P. Acanthamoeba keratitis. The value of early diagnosis. Ophthalmology 1993, 100, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, A.S.; Frazer, D.G.; Dart, J.K.; Matheson, M.; Ficker, L.A.; Wright, P. A review of 72 consecutive cases of Acanthamoeba keratitis, 1984–1992. Eye 1993, 7 Pt 6, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouheraoua, N.; Gaujoux, T.; Goldschmidt, P.; Chaumeil, C.; Laroche, L.; Borderie, V.M. Prognostic factors associated with the need for surgical treatments in acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea 2013, 32, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, D.S.J.; Gopal, B.P.; Deshmukh, R.; Seitzman, G.D.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S. Diagnostic armamentarium of infectious keratitis: A comprehensive review. Ocul. Surf. 2022, 23, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnt, N.; Minassian, D.C.; Dart, J.K.G. Acanthamoeba Keratitis Risk Factors for Daily Wear Contact Lens Users: A Case-Control Study. Ophthalmology 2023, 130, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Garg, P.; Motukupally, S.R.; Geary, M.B. Clinico-microbiological review of non-contact-lens-associated acanthamoeba keratitis. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2015, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.L.; Ong, Z.Z.; Marelli, L.; Pennacchi, A.; Lister, M.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S.; Ting, D.S.J. False positive microbiological results in Acanthamoeba keratitis: The importance of clinico-microbiological correlation. Eye 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvesvara, G.S.; Jones, D.B.; Robinson, N.M. Isolation, identification, and biological characterization of Acanthamoeba polyphaga from a human eye. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1975, 24, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilvington, S.; Larkin, D.F.; White, D.G.; Beeching, J.R. Laboratory investigation of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1990, 28, 2722–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yera, H.; Ok, V.; Lee Koy Kuet, F.; Dahane, N.; Ariey, F.; Hasseine, L.; Delaunay, P.; Martiano, D.; Marty, P.; Bourges, J.L. PCR and culture for diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 1302–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, J.W.Y.; Harrison, R.; Hau, S.; Alexander, C.L.; Tole, D.M.; Avadhanam, V.S. Comparison of In Vivo Confocal Microscopy, PCR and Culture of Corneal Scrapes in the Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Cornea 2018, 37, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, O.J.; Green, S.M.; Morlet, N.; Kilvington, S.; Keys, M.F.; Matheson, M.M.; Dart, J.K.; McGill, J.I.; Watt, P.J. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of corneal epithelial and tear samples in the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998, 39, 1261–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J.J.; Dart, J.K.G.; De, S.K.; Carnt, N.; Cleary, G.; Hau, S. Comparison of culture, confocal microscopy and PCR in routine hospital use for microbial keratitis diagnosis. Eye 2022, 36, 2172–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangon, F.B.; Miller, D.; Alfonso, E.C. Impact of prior therapy on the recovery and frequency of corneal pathogens. Cornea 2004, 23, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaselgrave, W.; Hamad, A.; Coles, S.; Hau, S. In Vitro Evaluation of the Inhibitory Effect of Topical Ophthalmic Agents on Acanthamoeba Viability. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2019, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, E.Y.; Shoff, M.E.; Gao, W.; Joslin, C.E. Effect of low concentrations of benzalkonium chloride on acanthamoebal survival and its potential impact on empirical therapy of infectious keratitis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013, 131, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifaoui, I.; Reyes-Batlle, M.; López-Arencibia, A.; Chiboub, O.; Rodríguez-Martín, J.; Rocha-Cabrera, P.; Valladares, B.; Piñero, J.E.; Lorenzo-Morales, J. Toxic effects of selected proprietary dry eye drops on Acanthamoeba. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagerfors, S.; Ejdervik-Lindblad, B.; Söderquist, B. Does the sampling instrument influence corneal culture outcome in patients with infectious keratitis? A retrospective study comparing cotton tipped applicator with knife blade. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2020, 5, e000363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muiño, L.; Rodrigo, D.; Villegas, R.; Romero, P.; Peredo, D.E.; Vargas, R.A.; Liempi, D.; Osuna, A.; Jercic, M.I. Effectiveness of sampling methods employed for Acanthamoeba keratitis diagnosis by culture. Int. Ophthalmol. 2019, 39, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, N.M.; Hikal, W.M. Several staining techniques to enhance the visibility of Acanthamoeba cysts. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marines, H.M.; Osato, M.S.; Font, R.L. The value of calcofluor white in the diagnosis of mycotic and Acanthamoeba infections of the eye and ocular adnexa. Ophthalmology 1987, 94, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.B.; Liesegang, T.J.; Robinson, N.M.; Washington, J.A. Laboratory Diagnosis of Ocular Infections; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Tananuvat, N.; Techajongjintana, N.; Somboon, P.; Wannasan, A. The First Acanthamoeba keratitis Case of Non-Contact Lens Wearer with HIV Infection in Thailand. Korean J. Parasitol. 2019, 57, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhardt, C.; Schweikert, R.; Hartmann, L.M.; Vounotrypidis, E.; Kilani, A.; Wolf, A.; Wertheimer, C.M. The role of the calcofluor white staining in the diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Ophthalmic Inflamm. Infect. 2023, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilhelmus, K.R.; Osato, M.S.; Font, R.L.; Robinson, N.M.; Jones, D.B. Rapid diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis using calcofluor white. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1986, 104, 1309–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, M.J.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Meenakshi, R.; Mittal, S.; Shivakumar, C.; Srinivasan, M. Microbiological diagnosis of infective keratitis: Comparative evaluation of direct microscopy and culture results. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 1271–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossniklaus, H.E.; Waring, G.O.T.; Akor, C.; Castellano-Sanchez, A.A.; Bennett, K. Evaluation of hematoxylin and eosin and special stains for the detection of acanthamoeba keratitis in penetrating keratoplasties. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 136, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.A.; Kuriakose, T. Rapid detection of Acanthamoeba cysts in corneal scrapings by lactophenol cotton blue staining. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1990, 108, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, J.B.; Chan, R.; Andersen, B.R. Rapid visualization of Acanthamoeba using fluorescein-conjugated lectins. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1988, 106, 1273–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Govic, Y.; Gonçalves, A.; de Gentile, L.; Pihet, M. Common staining techniques for highlighting Acanthamoeba cysts. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 970–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvany, R.E.; Luckenbach, M.W.; Moore, M.B. The rapid detection of Acanthamoeba in paraffin-embedded sections of corneal tissue with calcofluor white. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1987, 105, 1366–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayamajhee, B.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Henriquez, F.L.; Petsoglou, C.; Carnt, N. Acanthamoeba keratitis: An increasingly common infectious disease of the cornea. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e345–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehouse, G.; Reid, K.; Hudson, B.; Lennox, V.A.; Lawless, M.A. Corneal biopsy in microbial keratitis. Aust. N. Z. J. Ophthalmol. 1991, 19, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robaei, D.; Chan, U.T.; Khoo, P.; Cherepanoff, S.; Li, Y.C.; Hanrahan, J.; Watson, S. Corneal biopsy for diagnosis of recalcitrant microbial keratitis. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2018, 256, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, D.G.; Rallis, K.I.; Al-Aqaba, M.A.; Ting, D.S.J.; Dua, H.S. Surgical management of infectious keratitis. Ocul. Surf. 2021, 137, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, K.A.; Kappagoda, N.K.; Filipic, M.; Billson, F.A.; Christy, P. Microbiological and histopathological confirmation of acanthamebic keratitis. Pathology 1988, 20, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C.; Moore, M.B.; Kaufman, H.E. Corneal biopsy in chronic keratitis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1987, 105, 577–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.; Al-Khersan, H.; Carletti, P.; Miller, D.; Dubovy, S.R.; Amescua, G. Role of corneal biopsy in the management of infectious keratitis. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2022, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varacalli, G.; Di Zazzo, A.; Mori, T.; Dohlman, T.H.; Spelta, S.; Coassin, M.; Bonini, S. Challenges in Acanthamoeba Keratitis: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.; Green, W.R. Corneal biopsy. Indications, techniques, and a report of a series of 87 cases. Ophthalmology 1990, 97, 718–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, A.; Sarode, D.; Lockington, D.; Ramaesh, K. Novel Map Biopsy Technique to Define the Extent of Infection Before Penetrating Keratoplasty for Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Cornea 2023, 42, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompa, S.; Langefeld, S.; Kirchhof, B.; Schrage, N. Corneal biopsy in keratitis performed with the microtrephine. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1999, 237, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.G. Lamellar flap corneal biopsy. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993, 24, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J.; Leeming, J.; Coombs, G.; Pearman, J.; Sharma, A.; Illingworth, C.; Crawford, G.; Easty, D. Corneal biopsy with tissue micro-homogenisation for isolation of organisms in bacterial keratitis. Eye 1999, 13 Pt 4, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, S.H.; Kymionis, G.D.; O’Brien, T.P.; Ide, T.; Culbertson, W.; Alfonso, E.C. Femtosecond-assisted diagnostic corneal biopsy (FAB) in keratitis. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2008, 246, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Yum, J.H.; Lee, D.; Oh, S.H. Novel technique of corneal biopsy by using a femtosecond laser in infectious ulcers. Cornea 2008, 27, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.M.; Stiefel, H.C.; Houghton, D.C.; Chamberlain, W.D. Intraoperative Optical Coherence Tomography to Guide Corneal Biopsy: A Case Report. Cornea 2019, 38, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, T.F.; Corless, C.E.; Sueke, H.; Neal, T.; Kaye, S.B. 16S Ribosomal RNA PCR Versus Conventional Diagnostic Culture in the Investigation of Suspected Bacterial Keratitis. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudeh, Y.O.; Suresh, L.; Lister, M.; Dua, H.S.; Said, D.G.; Ting, D.S.J. Microbiology culture versus 16S/18S polymerase chain reaction for diagnosing infectious keratitis: A comparative study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 2333. [Google Scholar]

- Sarink, M.J.; Koelewijn, R.; Stelma, F.; Kortbeek, T.; van Lieshout, L.; Smit, P.W.; Tielens, A.G.M.; van Hellemond, J.J. An International External Quality Assessment Scheme to Assess the Diagnostic Performance of Polymerase Chain Reaction Detection of Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Cornea 2023, 42, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, L.; Fuentes-Utrilla, P.; Hodson, J.; O’Neil, J.D.; Rossiter, A.E.; Begum, G.; Suleiman, K.; Murray, P.I.; Wallace, G.R.; Loman, N.J.; et al. Evaluation of full-length nanopore 16S sequencing for detection of pathogens in microbial keratitis. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullis, K.B.; Faloona, F.A. Specific synthesis of DNA in vitro via a polymerase-catalyzed chain reaction. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; Volume 155, pp. 335–350. [Google Scholar]

- Booton, G.C.; Kelly, D.J.; Chu, Y.W.; Seal, D.V.; Houang, E.; Lam, D.S.; Byers, T.J.; Fuerst, P.A. 18S ribosomal DNA typing and tracking of Acanthamoeba species isolates from corneal scrape specimens, contact lenses, lens cases, and home water supplies of Acanthamoeba keratitis patients in Hong Kong. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 1621–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnikov, S.; Manakongtreecheep, K.; Söll, D. Revising the Structural Diversity of Ribosomal Proteins Across the Three Domains of Life. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1588–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.M.; Booton, G.C.; Hay, J.; Niszl, I.A.; Seal, D.V.; Markus, M.B.; Fuerst, P.A.; Byers, T.J. Use of subgenic 18S ribosomal DNA PCR and sequencing for genus and genotype identification of acanthamoebae from humans with keratitis and from sewage sludge. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1903–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qvarnstrom, Y.; Visvesvara, G.S.; Sriram, R.; da Silva, A.J. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Naegleria fowleri. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 3589–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.P.; Kowalski, R.P.; Shanks, R.M.; Gordon, Y.J. Validation of real-time PCR for laboratory diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 3232–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasricha, G.; Sharma, S.; Garg, P.; Aggarwal, R.K. Use of 18S rRNA gene-based PCR assay for diagnosis of acanthamoeba keratitis in non-contact lens wearers in India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 3206–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yera, H.; Zamfir, O.; Bourcier, T.; Ancelle, T.; Batellier, L.; Dupouy-Camet, J.; Chaumeil, C. Comparison of PCR, microscopic examination and culture for the early diagnosis and characterization of Acanthamoeba isolates from ocular infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007, 26, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, W.D.; Nelson, S.E.; Lane, J.L.; Wilson, M.E.; Allen, R.C.; Folberg, R. Confirmation of confocal microscopy diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis using polymerase chain reaction analysis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2000, 118, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldschmidt, P.; Rostane, H.; Saint-Jean, C.; Batellier, L.; Alouch, C.; Zito, E.; Bourcier, T.; Laroche, L.; Chaumeil, C. Effects of topical anaesthetics and fluorescein on the real-time PCR used for the diagnosis of Herpesviruses and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 90, 1354–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldschmidt, P.; Degorge, S.; Saint-Jean, C.; Yera, H.; Zekhnini, F.; Batellier, L.; Laroche, L.; Chaumeil, C. Resistance of Acanthamoeba to classic DNA extraction methods used for the diagnosis of corneal infections. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 92, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitzman, G.D.; Cevallos, V.; Margolis, T.P. Rose bengal and lissamine green inhibit detection of herpes simplex virus by PCR. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 141, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedbrauk, D.L.; Werner, J.C.; Drevon, A.M. Inhibition of PCR by aqueous and vitreous fluids. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 2643–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralik, P.; Ricchi, M. A Basic Guide to Real Time PCR in Microbial Diagnostics: Definitions, Parameters, and Everything. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maubon, D.; Dubosson, M.; Chiquet, C.; Yera, H.; Brenier-Pinchart, M.-P.; Cornet, M.; Savy, O.; Renard, E.; Pelloux, H. A One-Step Multiplex PCR for Acanthamoeba Keratitis Diagnosis and Quality Samples Control. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 2866–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mackay, I.M. Real-time PCR in the microbiology laboratory. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10, 190–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itahashi, M.; Higaki, S.; Fukuda, M.; Mishima, H.; Shimomura, Y. Utility of Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction in Diagnosing and Treating Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Cornea 2011, 30, 1233–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivière, D.; Szczebara, F.M.; Berjeaud, J.M.; Frère, J.; Héchard, Y. Development of a real-time PCR assay for quantification of Acanthamoeba trophozoites and cysts. J. Microbiol. Methods 2006, 64, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsenti, N.; Lau, R.; Purssell, A.; Chong-Kit, A.; Cunanan, M.; Gasgas, J.; Tian, J.; Wang, A.; Ralevski, F.; Boggild, A.K. Development and validation of a real-time PCR assay for the detection of clinical acanthamoebae. BMC Res. Notes 2017, 10, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- da Silva, A.J.; Pieniazek, N.J. Latest Advances and Trends in PCR-Based Diagnostic Methods. In Textbook-Atlas of Intestinal Infections in AIDS; Dionisio, D., Ed.; Springer: Milan, Italy, 2003; pp. 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, A.S.; Ranford-Cartwright, L.C. Real-time quantitative PCR in parasitology. TRENDS Parasitol. 2002, 18, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewara, A.; Khurana, S.; Yoonus, S.; Megha, K.; Tanwar, P.; Gupta, A.; Sehgal, R. Evaluation of Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay for Rapid Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 35, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Qing, Y.; Zicheng, S.; Shiying, S. Rapid and sensitive diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis by loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, T.-K.; Chen, J.-S.; Tsai, H.-C.; Tao, C.-W.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Kuo, Y.-J.; Ji, D.-D.; Rathod, J.; Hsu, B.-M. Efficient nested-PCR-based method development for detection and genotype identification of Acanthamoeba from a small volume of aquatic environmental sample. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu-Ming, S.; Xin, L.; Jia, L. Development of nano-polymerase chain reaction and its application. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2017, 45, 1745–1753. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, A.K.; Siddiqui, R.; Ahmed, S.M.K.; Gabriel, S.; Jalal, M.Z.; John, A.; Khan, N.A. hBN Nanoparticle-Assisted Rapid Thermal Cycling for the Detection of Acanthamoeba. Pathogens 2020, 9, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, S.; Rasheed, A.K.; Siddiqui, R.; Appaturi, J.N.; Fen, L.B.; Khan, N.A. Development of nanoparticle-assisted PCR assay in the rapid detection of brain-eating amoebae. Parasitol. Res. 2018, 117, 1801–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, E.; Oliveira, M.; Portellinha, W.; de Freitas, D.; Nakano, K. Confocal microscopy in early diagnosis of Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Refract. Surg. 2004, 20, S737–S740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, J.D.; Prajna, N.V.; Larke, N.L.; Palepu, S.; Lanjewar, S.; Shah, M.; Elakkiya, S.; Lalitha, P.; Carnt, N.; Vesaluoma, M.H.; et al. Prospective Study of the Diagnostic Accuracy of the In Vivo Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope for Severe Microbial Keratitis. Ophthalmology 2016, 123, 2285–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, D.S.J.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S. Interface Haze After Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019, 137, 1201–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aqaba, M.A.; Dhillon, V.K.; Mohammed, I.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S. Corneal nerves in health and disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2019, 73, 100762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalbert, I.; Stapleton, F.; Papas, E.; Sweeney, D.F.; Coroneo, M. In vivo confocal microscopy of the human cornea. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 87, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthoff, R.F.; Zhivov, A.; Stachs, O. In vivo confocal microscopy, an inner vision of the cornea—A major review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009, 37, 100–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minsky, M. Memoir on inventing the confocal scanning microscope. Scanning 1988, 10, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petráň, M.; Hadravský, M.; Egger, M.D.; Galambos, R. Tandem-scanning reflected-light microscope. JOSA 1968, 58, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, B.R.; Thaer, A.A. Real-time scanning slit confocal microscopy of the invivohuman cornea. Appl. Opt. 1994, 33, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhivov, A.; Stachs, O.; Stave, J.; Guthoff, R.F. In vivo three-dimensional confocal laser scanning microscopy of corneal surface and epithelium. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2009, 93, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, R.H.; Hughes, G.W. Scanning laser ophthalmoscope. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1981, 28, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, R.H.; Hughes, G.W.; Delori, F.C. Confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Appl. Opt. 1987, 26, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, R.H.; Hughes, G.W.; Pomerantzeff, O. Flying spot TV ophthalmoscope. Appl. Opt. 1980, 19, 2991–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stave, J.; Zinser, G.; Grümmer, G.; Guthoff, R. Modified Heidelberg Retinal Tomograph HRT. Initial results of in vivo presentation of corneal structures. Ophthalmologe 2002, 99, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, D.S.J.; Ho, C.S.; Cairns, J.; Gopal, B.P.; Elsahn, A.; Al-Aqaba, M.; Boswell, T.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S. Seasonal patterns of incidence, demographic factors and microbiological profiles of infectious keratitis: The Nottingham Infectious Keratitis Study. Eye 2021, 35, 2543–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthoff, R.F.; Baudouin, C.; Stave, J. Atlas of Confocal Laser Scanning In-Vivo Microscopy in Ophthalmology; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Labbé, A.; Khammari, C.; Dupas, B.; Gabison, E.; Brasnu, E.; Labetoulle, M.; Baudouin, C. Contribution of in vivo confocal microscopy to the diagnosis and management of infectious keratitis. Ocul. Surf. 2009, 7, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petroll, W.M.; Robertson, D.M. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy of the Cornea: New Developments in Image Acquisition, Reconstruction, and Analysis Using the HRT-Rostock Corneal Module. Ocul. Surf. 2015, 13, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachs, O.; Guthoff, R.F.; Aumann, S. In Vivo Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy. In High Resolution Imaging in Microscopy and Ophthalmology: New Frontiers in Biomedical Optics; Bille, J.F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Cañadas, P.; Alberquilla García-Velasco, M.; Hernández Verdejo, J.L.; Teus, M.A. Update on Corneal Confocal Microscopy Imaging. Diagnostics 2022, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, S.; Sperlich, K.; Stahnke, T.; Schünemann, M.; Stolz, H.; Guthoff, R.F.; Stachs, O. Multiwavelength confocal laser scanning microscopy of the cornea. Biomed. Opt. Express 2020, 11, 5689–5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jester, J.V.; Cavanagh, H.D.; Black, T.D.; Petroll, W.M. On-line 3-dimensional confocal imaging in vivo. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 2945–2953. [Google Scholar]

- Mathers, W.; Littlefield, T.; Lakes, R.; Lane, J.A.; Daley, T.E. Observation of the retina using the tandem scanning confocal microscope. Scanning 1996, 18, 362–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidek Technologies. Nidek Confoscan 4 Brochure. 2001. Available online: https://www.nidektechnologies.it/media/uploads/allegati/4/cs4-brochure-eng-20090401.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Elliott, A.D. Confocal Microscopy: Principles and Modern Practices. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2020, 92, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.E.; Tepelus, T.C.; Vickers, L.A.; Baghdasaryan, E.; Gui, W.; Huang, P.; Irvine, J.A.; Sadda, S.; Hsu, H.Y.; Lee, O.L. Role of in vivo confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of infectious keratitis. Int. Ophthalmol. 2019, 39, 2865–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaddavalli, P.K.; Garg, P.; Sharma, S.; Sangwan, V.S.; Rao, G.N.; Thomas, R. Role of Confocal Microscopy in the Diagnosis of Fungal and Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanavi, M.R.; Javadi, M.; Yazdani, S.; Mirdehghanm, S. Sensitivity and specificity of confocal scan in the diagnosis of infectious keratitis. Cornea 2007, 26, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfister, D.R.; Cameron, J.D.; Krachmer, J.H.; Holland, E.J. Confocal microscopy findings of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 121, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, H.D.; McCulley, J.P. In vivo confocal microscopy and Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 121, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, W.D. Acanthamoeba: A Difficult Pathogen to Evaluate and Treat. Cornea 2004, 23, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrakis, G.; Haimovici, R.; Miller, D.; Alfonso, E.C. Corneal biopsy in the management of progressive microbial keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2000, 129, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, T.; Matthew, M.; Donald, F.; Maharajan, S.; Dua, H.S. In vivo confocal microscopy in the diagnosis and management of acanthamoeba keratitis showing new cystic forms. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009, 37, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, A.; Yokogawa, H.; Yamazaki, N.; Ishibashi, Y.; Oikawa, Y.; Tokoro, M.; Sugiyama, K. In Vivo Laser Confocal Microscopy Findings of Radial Keratoneuritis in Patients with Early Stage Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Ophthalmology 2013, 120, 1348–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidambaram, J.D.; Prajna, N.V.; Palepu, S.; Lanjewar, S.; Shah, M.; Elakkiya, S.; Macleod, D.; Lalitha, P.; Burton, M.J. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Cellular Features of Host and Organism in Bacterial, Fungal, and Acanthamoeba Keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 190, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovakimyan, M.; Falke, K.; Stahnke, T.; Guthoff, R.; Witt, M.; Wree, A.; Stachs, O. Morphological analysis of quiescent and activated keratocytes: A review of ex vivo and in vivo findings. Curr. Eye Res. 2014, 39, 1129–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, H.D.; Petroll, W.M.; Alizadeh, H.; He, Y.-G.; McCulley, J.P.; Jester, J.V. Clinical and diagnostic use of in vivo confocal microscopy in patients with corneal disease. Ophthalmology 1993, 100, 1444–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jester, J.V.; Brown, D.; Pappa, A.; Vasiliou, V. Myofibroblast differentiation modulates keratocyte crystallin protein expression, concentration, and cellular light scattering. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012, 53, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokogawa, H.; Kobayashi, A.; Yamazaki, N.; Ishibashi, Y.; Oikawa, Y.; Tokoro, M.; Sugiyama, K. Bowman’s layer encystment in cases of persistent Acanthamoeba keratitis. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2012, 6, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, X.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, S.; Labbé, A. A new in vivo confocal microscopy prognostic factor in Acanthamoeba keratitis. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2014, 37, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, S.C.; Dart, J.K.G.; Vesaluoma, M.; Parmar, D.N.; Claerhout, I.; Bibi, K.; Larkin, D.F.P. Diagnostic accuracy of microbial keratitis with in vivo scanning laser confocal microscopy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2010, 94, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, M.; Uhlhorn, S.R.; De Freitas, C.; Ho, A.; Manns, F.; Parel, J.M. Imaging and full-length biometry of the eye during accommodation using spectral domain OCT with an optical switch. Biomed. Opt. Express 2012, 3, 1506–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werkmeister, R.M.; Sapeta, S.; Schmidl, D.; Garhöfer, G.; Schmidinger, G.; Aranha Dos Santos, V.; Aschinger, G.C.; Baumgartner, I.; Pircher, N.; Schwarzhans, F.; et al. Ultrahigh-resolution OCT imaging of the human cornea. Biomed. Opt. Express 2017, 8, 1221–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, M.; Baskaran, M.; Werkmeister, R.M.; Chua, J.; Schmidl, D.; Aranha dos Santos, V.; Garhöfer, G.; Mehta, J.S.; Schmetterer, L. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 66, 132–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantopoulos, A.; Kuo, J.; Anderson, D.; Hossain, P. Assessment of the use of anterior segment optical coherence tomography in microbial keratitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 146, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantopoulos, A.; Yadegarfar, G.; Fievez, M.; Anderson, D.F.; Hossain, P. In vivo quantification of bacterial keratitis with optical coherence tomography. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1093–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Swanson, E.A.; Lin, C.P.; Schuman, J.S.; Stinson, W.G.; Chang, W.; Hee, M.R.; Flotte, T.; Gregory, K.; Puliafito, C.A.; et al. Optical Coherence Tomography. Science 1991, 254, 1178–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izatt, J.A.; Hee, M.R.; Swanson, E.A.; Lin, C.P.; Huang, D.; Schuman, J.S.; Puliafito, C.A.; Fujimoto, J.G. Micrometer-scale resolution imaging of the anterior eye in vivo with optical coherence tomography. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1994, 112, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E.A.; Izatt, J.A.; Hee, M.R.; Huang, D.; Lin, C.P.; Schuman, J.S.; Puliafito, C.A.; Fujimoto, J.G. In vivo retinal imaging by optical coherence tomography. Opt. Lett. 1993, 18, 1864–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, M.T.; Rao, H.L.; Zangwill, L.M.; Weinreb, R.N.; Medeiros, F.A. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracies of the Spectralis, Cirrus, and RTVue optical coherence tomography devices in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2011, 118, 1334–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bald, M.; Li, Y.; Huang, D. Anterior chamber angle evaluation with fourier-domain optical coherence tomography. J. Ophthalmol. 2012, 2012, 103704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Rollins, A.M.; Roth, J.E.; Yazdanfar, S.; Westphal, V.; Bardenstein, D.S.; Izatt, J.A. Real-time optical coherence tomography of the anterior segment at 1310 nm. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rio-Cristobal, A.; Martin, R. Corneal assessment technologies: Current status. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2014, 59, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitgeb, R.; Hitzenberger, C.K.; Fercher, A.F. Performance of fourier domain vs. time domain optical coherence tomography. Opt. Express 2003, 11, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.L.; Li, Y.; Huang, D. Clinical and research applications of anterior segment optical coherence tomography—A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009, 37, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Abou Shousha, M.; Perez, V.L.; Karp, C.L.; Yoo, S.H.; Shen, M.; Cui, L.; Hurmeric, V.; Du, C.; Zhu, D.; et al. Ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography for imaging the anterior segment of the eye. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging 2011, 42, S15–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youngquist, R.C.; Carr, S.; Davies, D.E. Optical coherence-domain reflectometry: A new optical evaluation technique. Opt. Lett. 1987, 12, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhoff, W.; Ulrich, R. Optical frequency domain reflectometry in single-mode fiber. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1981, 39, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angmo, D.; Nongpiur, M.E.; Sharma, R.; Sidhu, T.; Sihota, R.; Dada, T. Clinical utility of anterior segment swept-source optical coherence tomography in glaucoma. Oman J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 9, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiao, S.; Ruggeri, M.; Shousha, M.A.; Chen, Q. In situ visualization of tears on contact lens using ultra high resolution optical coherence tomography. Eye Contact Lens 2009, 35, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Tao, A.; Shen, M.; Jiao, S.; Lu, F. Ultrahigh-resolution measurement by optical coherence tomography of dynamic tear film changes on contact lenses. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 1988–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shousha, M.A.; Perez, V.L.; Wang, J.; Ide, T.; Jiao, S.; Chen, Q.; Chang, V.; Buchser, N.; Dubovy, S.R.; Feuer, W.; et al. Use of ultra-high-resolution optical coherence tomography to detect in vivo characteristics of Descemet’s membrane in Fuchs’ dystrophy. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.J.; Galor, A.; Nanji, A.A.; El Sayyad, F.; Wang, J.; Dubovy, S.R.; Joag, M.G.; Karp, C.L. Ultra high-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis and management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ocul. Surf. 2014, 12, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Optopol technology. SOCT Copernicus HR. 2014. Available online: https://www.oftis-opta.cz/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/SOCT-COPERNICUS_HR.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Topcon Healthcare. DRI OCT Triton Series—A Multimodal Swept Source OCT; 2022; Volume 2023, Available online: https://cdn.brandfolder.io/I6S47VV/at/mpr52hhh3fwmtb65sgp668bb/US_Triton_Brochure_Revised_MCA4483.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Optovue Inc. Optovue Iseries. 2022. Available online: http://www.medicalsintl.com/Content/uploads/Division/140612043258385~iVue%20Sales%20Brochure%20INTL-1up.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Yamazaki, N.; Kobayashi, A.; Yokogawa, H.; Ishibashi, Y.; Oikawa, Y.; Tokoro, M.; Sugiyama, K. In vivo imaging of radial keratoneuritis in patients with Acanthamoeba keratitis by anterior-segment optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 2153–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.M.; Lee, J.S.; Yoo, J.M.; Park, J.M.; Seo, S.W.; Chung, I.Y.; Kim, S.J. Comparison of anterior segment optical coherence tomography findings in acanthamoeba keratitis and herpetic epithelial keratitis. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 11, 1416–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampat, R.; Deshmukh, R.; Chen, X.; Ting, D.S.W.; Said, D.G.; Dua, H.S.; Ting, D.S.J. Artificial Intelligence in Cornea, Refractive Surgery, and Cataract: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 10, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Yu, D. Deep learning: Methods and applications. Found. Trends® Signal Process. 2014, 7, 197–387. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; He, Y.; Keel, S.; Meng, W.; Chang, R.T.; He, M. Efficacy of a Deep Learning System for Detecting Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy Based on Color Fundus Photographs. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassmann, F.; Mengelkamp, J.; Brandl, C.; Harsch, S.; Zimmermann, M.E.; Linkohr, B.; Peters, A.; Heid, I.M.; Palm, C.; Weber, B.H.F. A Deep Learning Algorithm for Prediction of Age-Related Eye Disease Study Severity Scale for Age-Related Macular Degeneration from Color Fundus Photography. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermany, D.S.; Goldbaum, M.; Cai, W.; Valentim, C.C.S.; Liang, H.; Baxter, S.L.; McKeown, A.; Yang, G.; Wu, X.; Yan, F.; et al. Identifying Medical Diagnoses and Treatable Diseases by Image-Based Deep Learning. Cell 2018, 172, 1122–1131.e1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, D.S.W.; Cheung, C.Y.; Lim, G.; Tan, G.S.W.; Quang, N.D.; Gan, A.; Hamzah, H.; Garcia-Franco, R.; San Yeo, I.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; et al. Development and Validation of a Deep Learning System for Diabetic Retinopathy and Related Eye Diseases Using Retinal Images From Multiethnic Populations With Diabetes. Jama 2017, 318, 2211–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Cho, K.J.; Oh, S. Development of machine learning models for diagnosis of glaucoma. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, C.; Nie, D.; Lin, D.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, L.; Xu, F.; Jin, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. A deep learning system for identifying lattice degeneration and retinal breaks using ultra-widefield fundus images. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, C.; Nie, D.; Lin, D.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, C.; Xiang, Y.; Xu, F.; Jin, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Development and Evaluation of a Deep Learning System for Screening Retinal Hemorrhage Based on Ultra-Widefield Fundus Images. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Guo, C.; Nie, D.; Lin, D.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wu, X.; Xu, F.; Jin, C.; Zhang, X.; et al. Deep learning for detecting retinal detachment and discerning macular status using ultra-widefield fundus images. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Jiang, J.; Chen, K.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, X.; Weng, H.; Wu, S.; Chen, W. Preventing corneal blindness caused by keratitis using artificial intelligence. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, N.; Shih, A.K.; Lin, C.; Kuo, M.T.; Hwang, Y.S.; Wu, W.C.; Kuo, C.F.; Kang, E.Y.; Hsiao, C.H. Using Slit-Lamp Images for Deep Learning-Based Identification of Bacterial and Fungal Keratitis: Model Development and Validation with Different Convolutional Neural Networks. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Piech, C.; Baitemirova, M.; Prajna, N.V.; Srinivasan, M.; Lalitha, P.; Villegas, N.; Balachandar, N.; Chua, J.T.; Redd, T.; et al. Differentiation of Active Corneal Infections from Healed Scars Using Deep Learning. Ophthalmology 2022, 129, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.B.; Armstrong, G.W. Characterizing Infectious Keratitis Using Artificial Intelligence. Int. Ophthalmol. Clin. 2022, 62, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Z.Z.; Sadek, Y.; Liu, X.; Qureshi, R.; Liu, S.H.; Li, T.; Sounderajah, V.; Ashrafian, H.; Ting, D.S.W.; Said, D.G.; et al. Diagnostic performance of deep learning in infectious keratitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e065537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, G.; Gao, C.; Li, C.; Hu, B.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q. Deep Learning for Three Types of Keratitis Classification based on Confocal Microscopy Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Signal Processing and Machine Learning, Beijing, China, 15 October 2020; pp. 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, K.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Q.; Huang, W.; Cui, L.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Shen, C.; et al. Deep learning-based automated diagnosis of fungal keratitis with in vivo confocal microscopy images. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essalat, M.; Abolhosseini, M.; Le, T.H.; Moshtaghion, S.M.; Kanavi, M.R. Interpretable deep learning for diagnosis of fungal and acanthamoeba keratitis using in vivo confocal microscopy images. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, K.; Ou, Z.; Liang, Q. Deep learning-based classification of infectious keratitis on slit-lamp images. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2022, 13, 20406223221136071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, A.; Miyazaki, D.; Nakagawa, Y.; Ayatsuka, Y.; Miyake, H.; Ehara, F.; Sasaki, S.I.; Shimizu, Y.; Inoue, Y. Determination of probability of causative pathogen in infectious keratitis using deep learning algorithm of slit-lamp images. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, S.; McPherson, J.D.; McCombie, W.R. Coming of age: Ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ung, L.; Bispo, P.J.; Doan, T.; Van Gelder, R.N.; Gilmore, M.S.; Lietman, T.; Margolis, T.P.; Zegans, M.E.; Lee, C.S.; Chodosh, J. Clinical metagenomics for infectious corneal ulcers: Rags to riches? Ocul. Surf. 2020, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Borroni, D.; Romano, V.; Kaye, S.B.; Somerville, T.; Napoli, L.; Fasolo, A.; Gallon, P.; Ponzin, D.; Esposito, A.; Ferrari, S. Metagenomics in ophthalmology: Current findings and future prospectives. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2019, 4, e000248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ting, D.S.J.; Chodosh, J.; Mehta, J.S. Achieving diagnostic excellence for infectious keratitis: A future roadmap. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1020198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Breitwieser, F.P.; Lu, J.; Jun, A.S.; Asnaghi, L.; Salzberg, S.L.; Eberhart, C.G. Identifying Corneal Infections in Formalin-Fixed Specimens Using Next Generation Sequencing. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgaard, D.B.; Barnadas, C.; Mirbarati, S.H.; O’Brien Andersen, L.; Nielsen, H.V.; Stensvold, C.R. Detection and Identification of Acanthamoeba and Other Nonviral Causes of Infectious Keratitis in Corneal Scrapings by Real-Time PCR and Next-Generation Sequencing-Based 16S-18S Gene Analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2021, 59, e02224-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Tandem Scanning IVCM * | Scanning Slit IVCM | Laser Scanning IVCM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main example | Tandem Scanning Confocal Microscope Tandem Scanning Corporation (Reston, Va, USA) | ConfoScan 4 Nidek Technologies (Gamagori, Japan/Padova, Italy) | Heidelberg retina tomograph and Rostock cornea module (HRT-RCM) Heidelberg Engineering (Heidelberg, Germany) |

| Light source | Mercury and Xenon [152] | Halogen [148,152,153] | Diode laser [148,149] |

| Light source wavelength | 400–700 nm [152] | 370–510 nm [152] | 670 nm [148] |

| Illumination and light detection | Rotating Nipkow disk (64,000 holes of 20–60 microns in diameter) [140,152] | Two conjugate slits [149,152] | Two scanning mirrors and one scanner [152] |

| Lateral resolution | N/A | 1 μm [137] | 1 μm [151] |

| Axial resolution | 9 μm [150,154] | 24 μm [150] | 7–8 μm [142,150] |

| Magnification | 60× ** [155] | 500× [156] | 400× [149] |

| Advantages | Diffraction-limited resolution, optical sectioning, faster than LSCM [157] | Faster scanning [157] | Diffraction-limited resolution, versatile, optical sectioning [157] |

| Disadvantages | Pinhole cross-talk, artefacts from disc–camera synchronisation, fixed pinhole size, phototoxicity [157] | Lower resolution [157] | Phototoxicity, slow speed, axial resolution at depth [157] |

| Characteristic | Time-Domain OCT | Fourier-Domain OCT | Ultra-High-Resolution OCT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral-Domain OCT | Swept-Source OCT | |||

| Examples in clinical use | 1. Visante OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany) 2. Heidelberg slit lamp OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) | Spectralis (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) 2. iVue80 (Optovue, Inc., Fremont, CA, USA) 3. Cirrus OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany) | 1. Casia SS-1000 OCT (Tomey, Nagoya, Japan) 2. Triton OCT (Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) | 1. SOCT Copernicus HR (Optopol Technologies SA, Zawiercie, Poland) |

| Optical source | Superluminescent diode [176] | Superluminescent diode [176] | Swept-source laser [176] | Superluminescent diode [176] |

| Wavelength | 1 = 1310 2 = 1310 nm [183,184,185] | 1 = 820 nm 2 = 840 nm 3 = 840 nm [176] | 1 = 1310 nm 2 = 1310 nm [176] | 1 = 850 nm [196] |

| Scan width | 1 = 16 mm 2 = 15 mm [183,184,185] | 1 = 6 mm 2 = 13 mm 3 = 6 mm [176] | 1 = 16 mm 2 = 16 mm [176,197] | 1 = 10 mm [196] |

| Scan depth | 1 = 6 mm 2 = 7 mm [183,184,185] | 1 = 2 mm 2 = 2–2.3 mm (retina) 3 = 2 mm [176,198] | 1 = 6 mm 2 = 6 mm [176] | N/A ** |

| Axial resolution * | 1 = 18 μm 2 = >25 μm [183,184,185] | 1 = 7 μm 2 = 5 μm 3 = 5 μm [176,198] | 1 = 10 μm 2 = 8 μm [176] | 1 = 3 μm [196] |

| Transverse resolution * | 1 = 60 μm 2 = 20–100 μm [183,184,185] | 1 = 20 μm 2 = 15 μm 3 = 15 μm [176,198] | 1 = 30 μm 2 = 30 μm [176] | 1 = 12–18 μm [196] |

| A-scan rate | 1 = 2000 scans/s 2 = 200 scans/s [176,186] | 1 = 40,000 scans/s 2 = 80,000 scans/s 3 = 27,000 scans/s [176,198] | 1 = 30,000 scans/s 2 = 100,000 scans/s [176] | 1 = 52,000 scans/s [196] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azzopardi, M.; Chong, Y.J.; Ng, B.; Recchioni, A.; Logeswaran, A.; Ting, D.S.J. Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Past, Present and Future. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2655. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13162655

Azzopardi M, Chong YJ, Ng B, Recchioni A, Logeswaran A, Ting DSJ. Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Past, Present and Future. Diagnostics. 2023; 13(16):2655. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13162655

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzzopardi, Matthew, Yu Jeat Chong, Benjamin Ng, Alberto Recchioni, Abison Logeswaran, and Darren S. J. Ting. 2023. "Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Past, Present and Future" Diagnostics 13, no. 16: 2655. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13162655

APA StyleAzzopardi, M., Chong, Y. J., Ng, B., Recchioni, A., Logeswaran, A., & Ting, D. S. J. (2023). Diagnosis of Acanthamoeba Keratitis: Past, Present and Future. Diagnostics, 13(16), 2655. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics13162655