Abstract

Background: The category of the “stromal tumors of the lower female genital tract” encompasses a wide spectrum of lesions with variable heterogeneity, which can be nosologically classified on the basis of their morphologic and immunohistochemical profiles as deep (aggressive) angiomyxoma (DAM), cellular angiofibroma (CAF), angiomyofibroblastoma (AMFB) or myofibroblastoma (MFB). Despite the differential diagnosis between these entities being usually straightforward, their increasingly recognized unusual morphological variants, along with the overlapping morphological and immunohistochemical features among these tumours, may raise serious differential diagnostic problems. Methods and Results: The data presented in the present paper have been retrieved from the entire published literature on the PubMed website about DAM, CAF, AFMB and MFB from 1984 to 2021. The selected articles are mainly represented by small-series, and, more rarely, single-case reports with unusual clinicopathologic features. The present review focuses on the diagnostic clues of the stromal tumours of the lower female genital tract to achieve a correct classification. The main clinicopathologic features of each single entity, emphasizing their differential diagnostic clues, are discussed and summarized in tables. Representative illustrations, including the unusual morphological variants, of each single tumour are also provided. Conclusion: Awareness by pathologists of the wide morphological and immunohistochemical spectrum exhibited by these tumours is crucial to achieve correct diagnoses and to avoid confusion with reactive conditions or other benign or malignant entities.

1. Introduction

The category of the “stromal tumours of the lower female genital tract” covers a wide spectrum of lesions with variable morphological and immunohistochemical heterogeneity. They arise from the specialized, hormonally responsive stroma of the lower female genital tract, and, based on morphological and immunohistochemical features, at least four tumour entities can be nosologically recognized: (i) deep (aggressive) angiomyxoma (DAM); (ii) cellular angiofibroma (CAF); (iii) angiomyofibroblastoma (AMFB) and (iv) myofibroblastoma (MFB) [1,2]. Among these tumours, it is crucial to distinguish DAM from the others due to its relatively high risk of local recurrence. Differential diagnosis between these entities is usually straightforward if the typical morphology and clinicopathologic features are encountered. However, some tumours may share several morphological and immunohistochemical features, along with unusual morphologies, raising serious differential diagnostic problems. As MFB, CAF and AMFB may also share chromosomal aberrations, namely a 13q14 deletion (MFB and CAF) or MTG1–CYP2E1 fusion transcripts (AMFB and MFB), it is likely that they are histogenetically related, as previously suggested [3,4,5]. Notably, a recent article emphasized the possibility that CAF may occur with other mesenchymal tumours showing the same 13q14 deletion, such as spindle-cell lipoma and mammary-type MFB [6].

Based on these morphological, immunohistochemical and cytogenetic findings, the hypothesis that vulvovaginal CAF, MFB and AMFB are in the spectrum of a single entity, likely arising from a common precursor stromal cell of the lower female genital tract, has been postulated [3,4,5,6,7]. The present overview focuses on the diagnostic clues of the stromal tumours of the lower female genital tract to aid in achieving correct classification. The main clinicopathologic features of each single entity, emphasizing their differential diagnostic clues, are discussed and summarized in tables. Representative illustrations, including their unusual morphological variants, of each single tumour are also provided. Awareness by pathologists of the wide morphological and immunohistochemical spectrum exhibited by these tumours is crucial to achieve a correct diagnosis and to avoid confusion with reactive conditions or other benign or malignant entities.

2. Materials and Methods

The data presented in the present paper have been retrieved by the entire published literature on the PubMed website about DAM, CAF, AFMB and MFB from 1984 to 2021. The selected articles were mainly represented by small-series (due to the relative rarity of these tumours) and, more rarely, by single-case reports with unusual clinicopathologic features. The histological illustrations have been retrieved from a personal consultation series of DAM, CAF, AMFB and MFB (63 cases) by Prof. G. Magro. The morphological and immunohistochemical diagnostic clues for each single tumour are provided. In addition, the unusual morphological features that can be diagnostically challenging are emphasized in the form of tables.

3. Results

3.1. Deep (Aggressive) Angiomyxoma (DAM)

DAM is a rare, locally infiltrative and non-metastasizing myofibroblastic stromal tumour first described by Steeper and Rosai in 1983 [8]. The tumour is diagnosed predominantly in reproductive-aged females, with peak incidence in the third decade [1,2,8,9]. The vulvovaginal region, perineum and pelvis represent the most common sites in women, while sporadic cases have also been reported in the inguinal region, spermatic cord, scrotum and pelvic cavity in adult males [9]. Similarly to the other stromal tumours of the vulvovaginal region, DAM is often confused with Bartholin gland cysts or inguinal hernias. Clinically, DAM presents as a relatively circumscribed large, slowly growing multilobular or polypoid mass with extension into the surrounding tissues. The cut surface shows a glistening, gelatinous appearance and ranges in size from a few centimetres to 20 cm. The classic-type morphology of DAM is that of an infiltrative, uniformly hypocellular tumour composed of small-sized spindled or stellate cells, haphazardly interspersed in an abundant myxoedematous stroma rich in fine collagen fibrils and containing numerous small-to-medium/large-sized blood vessels [8,9,10,11,12,13] (Figure 1 and Figure 2). The neoplastic cells exhibit a bland-looking morphology with poorly defined, scant cytoplasm and round, hyperchromatic nuclei; mitoses are absent or rare (Table 1 and Figure 1). In approximately 30% of cases, isolated or small bundles of thin, smooth-muscle cells are scattered within the myxoid stroma, occasionally close to blood vessels [8,13] (Figure 3).

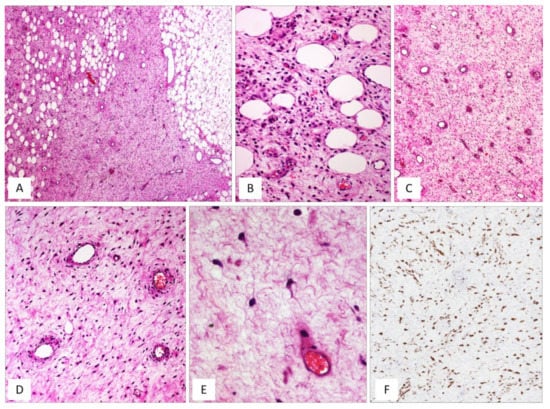

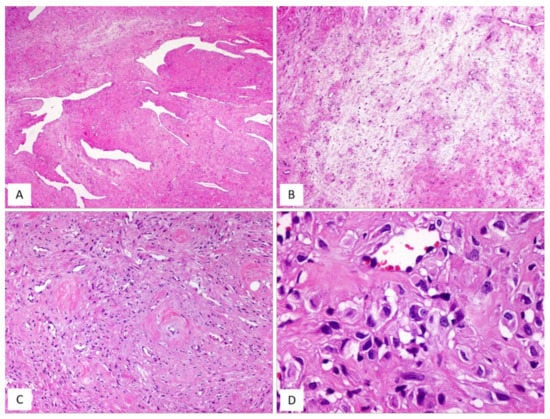

Figure 1.

DAM, classic type. (A) Tumour showing infiltrative margins into the surrounding adipose tissue (H and E, original magnification 50×). (B) Higher magnification: showing neoplastic cells intermingling with adipocytes (H and E, original magnification 200×). (C) Low magnification: showing a myxoid hypocellular tumour with numerous interspersed thin-walled blood vessels (H and E, original magnification 50×). (D) Tumour is composed of small-sized spindled or stellate cells (H and E, original magnification 200×). (E) Higher magnification: neoplastic cells exhibiting dendritic cytoplasmic processes (H and E, original magnification 300×). (F) Diffuse and strong immunoreactivity for desmin supports the myofibroblastic nature of the neoplastic cells (immunoperoxidase, original magnification 150×).

Figure 2.

DAM. (A) Classic-type DAM showing variable-sized blood vessels (H and E, original magnification 50×). (B–D) Unusual vascular features in DAM: (B) hyalinization of the vascular walls (H and E, original magnification 50×); (C) hyalinization of the vascular walls with total obliteration of their lumens (H and E, original magnification 50×); (D) capillary-like microvascular proliferation, as seen in glioblastoma (H and E, original magnification 200×).

Table 1.

Key diagnostic features of DAM.

Figure 3.

Unusual features in DAM. (A) Thin-sized mature smooth-muscle cells are haphazardly interspersed within myxoid tumour stroma (H and E, original magnification 300×). (B–D) Unusual features in DAM: (B) area with neurofibroma-like appearance; spindle cells with wavy nuclei, set in a collagenized stroma (H and E, original magnification 50×); (C) hypercellularity is seen around the blood vessels (H and E, original magnification 50×); (D) locally recurrent DAM; fibro-sclerotic tumour with interspersed thin-walled blood vessels (H and E, original magnification 50×).

Although the diagnosis of DAM is usually straightforward if the classic-type morphology is encountered, in a recent paper some clinicians reported that several unusual morphological features do exist, causing diagnostic problems, especially in recurrent tumours (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unusual morphological features of DAM [13].

By immunohistochemistry, DAM is typically a desmin-positive myofibroblastic tumour (Figure 1F) with variable expression of HMGA2 [14], α-smooth-muscle actin (from 27% to 95% of cases) and CD34 (from 17% to 50%) [13,15]. As some clinicians have previously observed in a previous article, it is likely that the morphological variations in cellular and stromal composition of DAM may reflect the plasticity of the neoplastic cells in adopting a myofibroblastic (vimentin+/desmin+/smooth-muscle actin+/−) or fibroblastic profile (vimentin+/desmin-/smooth-muscle actin-) in myxoid or fibrous stromal areas, respectively [13]. Despite its bland-looking morphology, DAM exhibits an infiltrative growth into the surrounding soft tissues and a risk of local recurrence. A wide local excision is difficult to achieve due to tumour-infiltrative margins, often evident at the histological examination alone. Recurrent tumours may show the same morphology of the primary lesion but hypercellular [11,12,13] or fibrosclerotic hypocellular tumours (Figure 3D) with hyalinized blood vessels (Figure 2B) and obliteration of their lumens (Figure 2C) can be seen [13]. In both hypercellular and hypocellular recurrent tumours, the identification of focal myxoid areas with the typical features of DAM is extremely helpful for a correct diagnostic interpretation [13]. In the past, DAM was considered to be a locally aggressive (destructive-type recurrence) tumour [1,2,10,11,12]. However, there is increasing evidence that this tumour has the tendency to locally recur in 9% to 50% of cases but the recurrence is of a non-invasive type in the majority of cases [9]. Accordingly, the original term “deep aggressive angiomyxoma” [8] has been changed into “deep angiomyxoma” (DAM) [9]. Recently, some clinicians have proposed the term “deep angiofibromyxoma” to emphasize that this tumour may frequently exhibit fibrous areas in both primary and recurrent lesions [13].

3.2. Cellular Angiofibroma (CAF)

CAF, originally described by Nucci et al. in 1997 [16], is a rare benign stromal tumour, fibroblastic rather than myofibroblastic in nature, usually occurring in the superficial (subcutaneous) soft tissues of the vulvovaginal region of middle-aged women [16,17]. Tumours with overlapping morphology have also been reported in the inguinoscrotal region of male patients, with the interchangeable terms “cellular angiofibroma or angiomyofibroblastoma-like tumor” [18]. Although most tumours are restricted to the pelvic area, extra-genital sites, including the retroperitoneum, pelvic and lumbar region, anus, urethra, trunk and oral mucosa have been rarely reported [17]. The most common clinical presentation is that of a slowly growing, painless mass ranging in size from 0.6 to 25 cm. Gross examination reveals a round-to-lobulated tumour mass with well-circumscribed margins. On cutting of the surface, CAF is grey-to-whitish in colour, with a firm-to-rubbery consistency (Figure 4A,B). Histologically, as its name suggests, the two main striking features of CAF are a population of spindle-shaped cells with a fibroblastic profile and a well-represented vascular component [16,17,19,20,21] (Table 3). It presents as a well-circumscribed, unencapsulated tumour, occasionally with limited infiltration of the surrounding adipose tissue [17,19]. CAF is a uniformly cellular neoplasm (moderately-to-focally highly cellular) composed of a proliferation of bland-looking spindle cells, set in a predominantly fibrous stroma containing bundles of wispy collagen fibres and numerous small- to medium-sized blood vessels, often with hyalinized walls (Figure 4C,D). The neoplastic cells, with the appearance of the fibroblasts, are cytologically bland and display oval-to-fusiform nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli and scant, often pale-to-eosinophilic cytoplasm. They are haphazardly distributed throughout the fibrous stroma, but they may adopt a fascicular arrangement (short, intersecting fascicles) or nuclear palisading (Figure 4E). Mitotic figures are rare. In the last two decades, several papers on CAF have emphasized the possibility of unusual morphological features that can represent potential diagnostic pitfalls (Figure 5A–D and Table 4). A small subset of cases display worrisome cytologic features, ranging from severe nuclear atypia with high mitotic activity (so-called “atypical CAF”) to, frankly, areas of sarcomatous transformation [22,23,24]. The atypical cells can be focally dispersed within the tumour (Figure 5C,D) or, more rarely, may show a vaguely nodular configuration [22,23,24]. The cases with sarcomatous dedifferentiation show—characteristically—an abrupt transition from a CAF not otherwise specified (NOS) to a discrete sarcomatous component [21,22]. The latter can be composed of areas resembling atypical lipomatous tumour, pleomorphic sarcoma or pleomorphic spindle-cell sarcoma [22,23,24]. The immunohistochemical profile is of fibroblastic-type, being CD34-expressed in most cases [16]; variable expression of myogenic markers, including α-SMA, desmin and h-caldesmon, has been occasionally reported, in 10–20% of cases [3,17]. Nuclear immunopositivity for ER and PR and nuclear loss of RB1 is frequently observed [17]. Notably, an overexpression of p16 has been documented restricted to the atypical cells and in the sarcomatous areas [23]. Most cases of CAF show a 13q14 deletion by F.I.S.H., as shown by the monoallelic loss of RB1 or FOXO1 at the 13q14 locus [19,21]. CAF is a benign tumour that can rarely recur after surgical excision [19,20,25]. Notably, the cases of atypical CAF or with sarcomatous dedifferentiation (less than 15 cases reported to date) have developed neither local recurrences nor metastases [22,23,24,25].

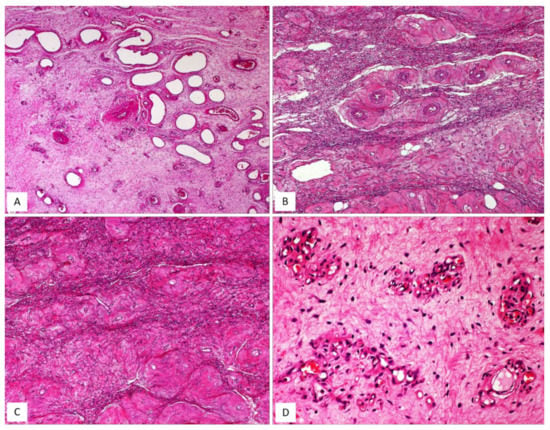

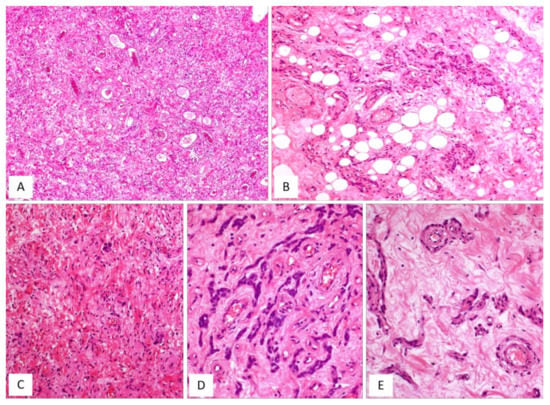

Figure 4.

CAF, classic type. (A) Gross appearance: oval-shaped mass with well-circumscribed margins; (B) the cut surface showing a solid mass, whitish in colour. (C) Fibrous tumour with pushing borders (H and E, original magnification 50×). (D) Spindle-shaped cells set in a fibrous stroma (H and E, original magnification 50×). (E) Tumour area with focal fascicular arrangement (H and E, original magnification 50×).

Table 3.

Key diagnostic features of CAF.

Figure 5.

CAF: unusual features. (A) CAF with numerous branching, thin-walled blood vessels (H and E, original magnification 50×). (B) Alternating fibrous-to-mixoedematous areas (H and E, original magnification 50×). (C) Low magnification: showing area with atypical cells (H and E, original magnification 100×). (D) Higher magnification: neoplastic cells with moderate/severe nuclear atypia (so-called “atypical CAF”) (H and E, original magnification 300×).

Table 4.

Unusual morphological features of CAF.

3.3. Angiomyofibroblastoma (AMFB)

AMFB is a benign, superficially located (subcutaneous) stromal tumour, firstly described by Fletcher et al. in 1992 [27], that mainly involves the vulva and vagina [28,29] of women in the reproductive or, less frequently (10% of cases), in the postmenopausal years [28,29]. The less frequently affected sites include the perineum, inguinal area and fallopian tubes [27]. Tumours with partial overlapping morphology have been reported in the inguinoscrotal region of male patients under the term of “AMFB/AMFB like-tumor” [18] but they are currently best regarded as CAF [29]. Patients typically present with a slowly growing, painless subcutaneous mass/swelling, measuring <5 cm in maximum diameter, frequently misinterpreted as a Bartholin gland cyst. Grossly, AMFB presents as a well-circumscribed, usually unencapsulated lesion, typically measuring <5 cm in its greatest diameter. Rarely, AMFB may present as a large pedunculated mass [30,31]. Histologically, as its name suggests, the two main striking features of AMFB are a population of cells with a fibroblastic/myofibroblastic profile and a well-represented vascular component. Histologically, AMFB is a well-circumscribed, unencapsulated or partially/totally encapsulated tumour showing alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas [32,33,34,35] (Table 5); it is composed of a proliferation of bland-looking spindled-to-epithelioid cells, arranged singly or in small nests or cords (Figure 6A–D) that tend to be clustered around blood vessels (Figure 6B,E). The epithelioid/plasmacytoid morphology is best appreciated in the hypercellular areas; a predominant spindle-cell morphology is more frequently observed in postmenopausal patients. The neoplastic cells, usually plump and with appreciable eosinophilic cytoplasm (better in cells with epithelioid morphology) and ovoid-to-spindle-shaped nuclei, are set in a variably myxoedematous-to-fibrous stroma (Figure 6B,C). Scattered mast cells and lymphocytes can be sparsely observed in the stroma. Mitotes are rare or absent. The vascular component is usually represented by thin-walled, capillary-like vessels (Figure 6A), but thick-walled, often hyalinized vessels, can be encountered. The presence of mature, fatty tissue, regarded as an integral part of the tumour and not merely entrapped peripheral adipose tissue, is a common feature, and, for when it represents at least 50% of the entire tumour, the term “lipomatous AMFB” has been proposed [36,37,38,39] (Figure 7A,B). Morphological variations on this common morphological theme have also been reported in AMFB (Table 6). Rarely, AMFB may contain atypical cells and high mitotic activity (so-called “malignant AMFB”) or, frankly, sarcomatous areas closely resembling leiomyosarcoma or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (so-called “dedifferentiated AMFB”) [40,41]. By means of immunohistochemistry, AMFB usually exhibits immunoreactivity for oestrogen receptors (Figure 7C), combined with a variable fibroblastic/myofibroblastic profile with the variable expression of desmin (Figure 7D) and α-smooth-muscle actin (up to 40% of cases) [5,42]. Although bcl-2, CD99, PR and AR are usually expressed in most cases, CD34 is detected, though only in a minority of cases [42]. Molecular studies have failed to detect HMGA1 and HMGA2 rearrangements [14] and the 13q14 deletion [36], the latter being a common finding in both CAF and MFB. In the sarcomatous component described by Nielsen et al. [40], the neoplastic cells are shown negative for desmin, SMA and CD34. Recently, the immunohistochemical strong expression of CYP2E1, as a surrogate marker of a novel genetic alteration, namely MTG1–CYP2E1 fusion, has been reported in AMFB [5]. AMFB is a benign tumour with occasional local recurrences, especially for those tumours not completely resected. Nevertheless, the recurrences are not destructive and, thus, easy to remove. Actually, AMFB should be considered a tumour with a very low risk of sarcomatous overgrowth/dedifferentiation. Only a single case of AMFB exhibiting sarcomatous dedifferentiation has locally recurred as a purely sarcomatous tumour [40]. Distant metastases have never been reported for either “malignant or dedifferentiated AMFBs”.

Table 5.

Key diagnostic features of AMFB.

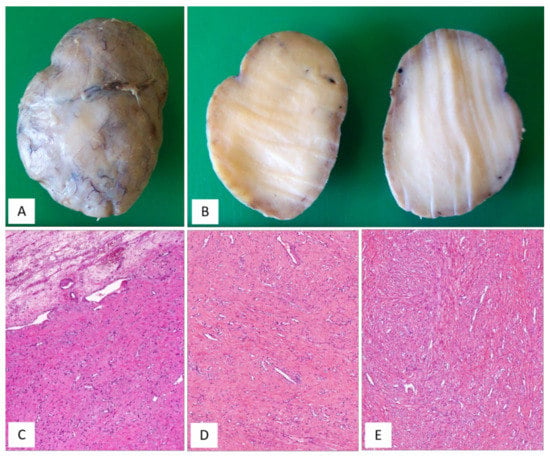

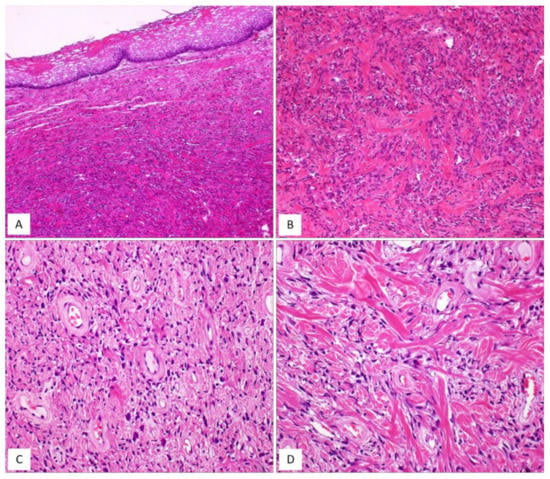

Figure 6.

AMFB, classic-type. (A) Low-magnification: mesenchymal tumour with numerous thin-walled blood vessels (H and E, original magnification 50×). (B) Fibromyxoid stroma containing neoplastic cells, mainly arranged around the blood vessels; single adipocytes are also seen (H and E, original magnification 100×). (C) Higher magnification: spindle cells are haphazardly set in a myxoid stroma containing wispy collagen fibres; focally neoplastic cells with epithelioid morphology are arranged in small nests (H and E, original magnification 100×). (D) Neoplastic cells exhibiting a cord-like growth pattern (H and E, original magnification 200×). (E) The perivascular clustering of neoplastic cells is a typical feature of AMFB (H and E, original magnification 200×).

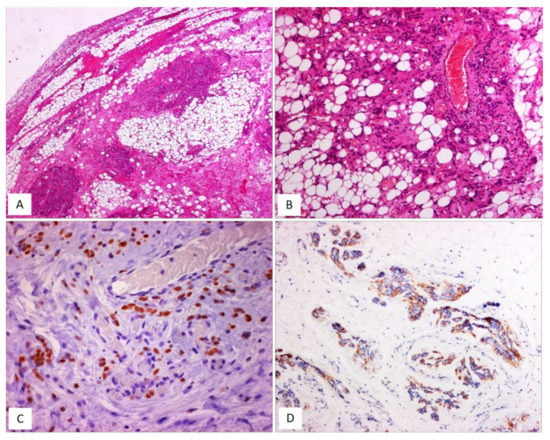

Figure 7.

AMFB, lipomatous type. (A) Low-magnification: a fibrofatty tumour with well-circumscribed margins (H and E, original magnification 50×). (B) Neoplastic cells intermingling with mature adipocytes (H and E, original magnification 100×). Neoplastic cells are often positive for oestrogen receptors (C) and desmin (D) (immunoperoxidase, original magnification 200×, C, and 100×, D).

Table 6.

Unusual morphological features of angiomyofibroblastoma.

3.4. Myofibroblastoma (MFB)

MFB of the lower female genital tract is a benign neoplasm composed of spindled cells with myofibroblastic profile, that arises from the subepithelial stroma of the vagina and, less frequently, of the vulva and cervix (Table 7) [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. MFB presents as a slowly growing, painless mass affecting mainly adults in their fifth or sixth decade of life. Grossly, tumours present as a well-circumscribed lesion of variable size (2–65 mm), showing a polypoid or nodular appearance. Histologically, MFB is a tumour centred in the subepithelial connective tissue, separated by the overlying epithelium by a thick band of native connective tissue (so-called “Grenz zone”) (Figure 8A). Two distinct subtypes of MFB can be recognized: (i) superficial MFB; (ii) mammary-type MFB. Superficial MFB is characterized by a proliferation of bland-looking, spindle-shaped or stellate cells set in a variably loose, oedematous-to-finely-collagenous stroma, often with reticular, lace-like or sieve-like changes [48,49,50,51,52,53,54] (Figure 8B–E). Tumours may exhibit a variable, moderate-to-high cellularity. The cells have a scant amount of pale-to-eosinophilic cytoplasm and oval-to-elongated-to-wavy nuclei with a small nucleolus; only rarely, mild nuclear atypia can be seen [48]. Mitotic activity is usually low (0–2 mitoses/10 high-power field). The vascular component is relatively inconspicuous and represented by small-sized blood vessels with hyalinized walls [51]. Mast cells are variably interspersed among neoplastic cells. Unlike superficial MFB, mammary-type MFB is composed of spindle-shaped cells, usually arranged in short fascicles with intervening keloid-like collagen fibres [51,52,53] (Figure 9A–D). The blood vessels often show hyalinization of their walls (Figure 9C). Immunohistochemical studies have shown that both superficial and mammary-type MFB are typically desmin+/α-SMA-myofibroblastic tumours [48,49,50,51,52,53,54] (Figure 8E). Apart from desmin, positive staining for CD99, CD34, Bcl-2, ER and PR can be detected in most cases [51]. In addition, about 90% of cases shows a loss of nuclear RB1 expression and the 13q14 deletion by F.I.S.H., confirming that MFB is pathogenetically related to other benign mesenchymal tumours showing a loss of 13q14, including spindle-cell lipoma and CAF [3]. As recently reported for AMFB, MFB also shows an overexpression of CY2E1 as a surrogate of MTG1–CYP2E1 fusion transcripts [5]. The clinical course is benign if a complete surgical excision is achieved. Only a single patient has been reported in the literature to experience a local recurrence (after 9 years) from surgical excision [50]; however, metastatic disease has never been reported.

Table 7.

Key diagnostic features of MFB.

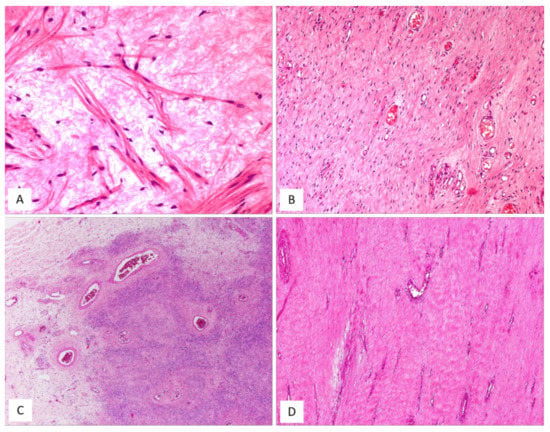

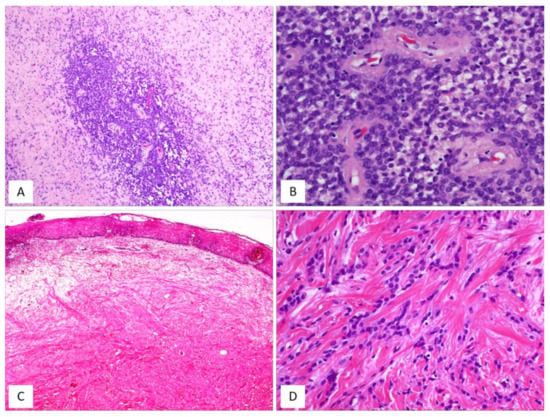

Figure 8.

MFB, superficial type. (A) Low magnification: mesenchymal tumour centred in the subepithelial connective tissue; a native collagen band is seen between the tumour and the overlying squamous epithelium (so-called “Grenz zone”) (H and E, original magnification 25×). (B) Tumour is composed of small-sized spindled-to-stellate cells set in collagenous stroma (H and E, original magnification 100×). (C) Higher magnification: microcystic and reticular (D) stromal changes. Neoplastic cells are strongly and diffusely positive to desmin (E) ((C,D) H and E and (E) immunoperoxidase; (C) original magnifications 100×, (D) 50× and (E) 200×).

Figure 9.

MFB, mammary type. (A) Low magnification: subepithelial fibrous mesenchymal tumour (H and E, original magnification 25×). (B) Spindle-shaped cells haphazardly arranged with interspersed thick, keloid-like collagen fibres (H and E, original magnification 50×). (C) Some areas may show bi- or multi-nucleated cells and hyalinized blood vessels (H and E, original magnification 50×). (D) Thick, keloid-like collagen fibres are a typical feature of mammary-type MFB (H and E, original magnification 50×).

Figure 10A–D and Table 8 summarize the unusual morphologic features that may be exhibited by superficial/mammary-type MFB.

Figure 10.

MFB, superficial/mammary type: unusual features. (A) Superficial-type MFB: an abrupt transition from a classic area into a hypercellular area (B) composed of bland-looking, small-sized, round, blue cells; mitoses and necrosis are absent (H and E, original magnifications (A) 50× and (B) 200×). (C) MFB, mammary type: the so-called fibrous/collagenized variant (H and E, original magnification 25×); (D) MFB may occasionally show, at least focally, a single-cell linear arrangement imparting to the tumour a pseudo-infiltrative growth pattern reminiscent of an invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast (H and E, original magnification 200×).

Table 8.

Unusual morphological features of MFB.

4. Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of the vulvovaginal stromal tumours may be challenging, as they share several clinical, morphological (Figure 11), immunohistochemical and genetic features. A correct nosological classification is not a mere academic exercise but crucial to differentiate tumours with benign biological behaviour (MFB, AMFB) from locally aggressive tumours (DAM) and from tumours with a low risk of malignant transformation (CAF). The most salient diagnostic features and the differential diagnostic clues are provided in the comparative Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11. CAF and MFB share a cellular composition (bland-looking spindle cells), the oedematous-to-fibrous stroma, the loss of nuclear RB1 expression by immunohistochemistry and the deletion of the 13q14 region by F.I.S.H. analyses. Unlike CAF—which is a subcutaneous tumour—MFB is a subepithelial-centred lesion and, as the name implies, it exhibits a more prominent vascular component than does MFB. In most cases, CAF shows a fibroblastic (CD34+/desmin-) rather than a myofibroblastic profile (desmin+). Occasionally, both CAF and MFB with extensive oedematous stroma may mimic DAM; however, the latter tumour is deep-seated, uniformly hypocellular and has infiltrative margins. Unlike DAM, which is usually a desmin-positive tumour with retained nuclear expression of RB1, CAF is desmin-negative, with the loss of nuclear RB1 immunoreactivity. Although DAM and MFB are desmin-positive tumours, these tumours harbour a different molecular signature; the former is often HMGA2-positive, as a surrogate of HMGA2 rearrangements, while the latter shows the absence of RB1 nuclear expression and the overexpression of CY2E1, respectively, as a surrogate of the 13q14 deletion and MTG1–CYP2E1 fusion transcripts [5]. AMFB may also be difficult to distinguish from DAM, CAF and MFB. AMFB differs from DAM in that the former has sharply circumscribed margins and epithelioid cells clustered around capillary-sized vessels. Conversely, DAM has infiltrative margins and contains larger and thicker-walled vessels. AMFB can be distinguished from CAF in that the latter has larger vessels with thick hyalinized walls, in contrast to the thin-walled, capillary-like vessels seen in AMFB. Finally, unlike MFB, AMFB is subcutaneously located and, at least focally, contains epithelioid cells with a perivascular arrangement. In contrast to CAF, AMFB does not show monoallelic deletions of RB1 and FOXO1 at the 13q14 locus but MTG1–CYP2E1 fusion transcripts are commonly identified.

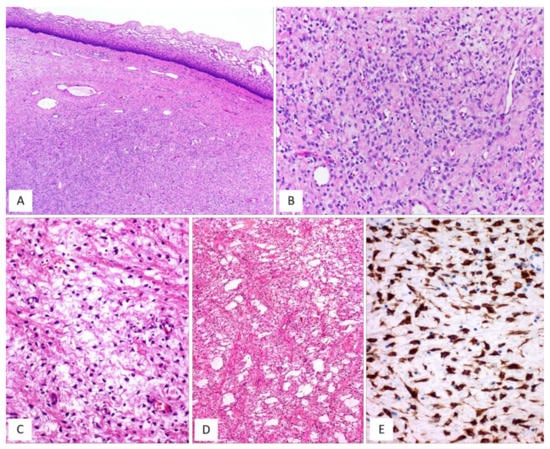

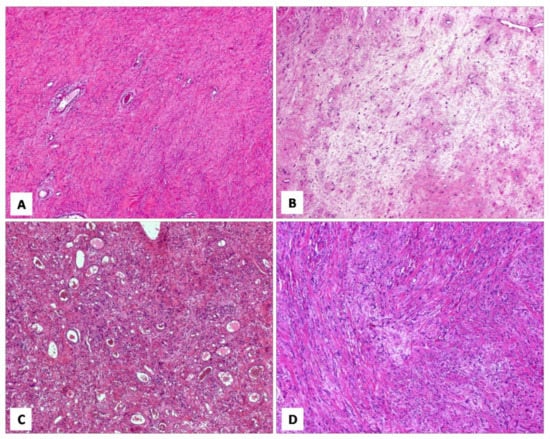

Figure 11.

Different histotypes with overlapping morphological features. (A) DAM: area with diffuse, collagenized stroma, mimicking CAF (H and E, original magnification 50×). (B) CAF: area with hypocellular myxoedematous stroma, mimicking DAM (H and E, original magnification 50×). (C) AMFB: area composed exclusively of spindled cells, mimicking CAF (H and E, original magnification 50×). (D) MFB: area with linear arrangement of neoplastic cells, mimicking AMFB (H and E, original magnification 200×).

Table 9.

Clinicopathologic features of the stromal tumours of the lower female genital tract.

Table 10.

Differential diagnosis: DAM vs. the other stromal tumours.

Table 11.

Differential diagnosis among CAF, AMFB and MFB.

5. Conclusions

Based on our experience in approaching the diagnosis of the benign stromal tumours of the lower female genital tract, namely DAM, CAF, AMFB and MFB, we strongly suggest adopting the following recommendations: (i) the diagnosis should be mainly based on histological features in combination with clinical and macroscopic features; (ii) immunohistochemical analyses may be misleading for correct tumour classification due to the non-specific results in the different histotypes; however, a diffuse desmin immunoreactivity in a tumour with abundant myxoid stroma is highly suggestive of DAM; (iii) in cases with ambiguous morphological and immunohistochemical features, F.I.S.H. analysis showing a 13q14 deletion is helpful in ruling out the diagnosis of DAM and AMFB; similarly, the detection of HMGA2 rearrangements by means of immunohistochemistry or molecular biology is helpful for the diagnosis of DAM; (iv) if the pathologist is dealing with a tumour exhibiting overlapping morphological features among the different histotypes (especially for CAF, AMFB and MFB) it could be a trivial problem to try to subtype a specific tumour at any cost and the use of the generic term “benign stromal tumour of the lower female genital tract” seems to be appropriate.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.A., S.M. and G.M.; methodology, G.A.; formal analysis, G.B.; resources, P.V., G.M.V. and L.S.; data curation, G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A. and G.M.; writing—review and editing, G.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McCluggage, W.G. A review and update of morphologically bland vulvovaginal mesenchymal lesions. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2005, 24, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCluggage, W.G. Recent developments in vulvovaginal pathology. Histopathology 2009, 54, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, G.; Righi, A.; Casorzo, L.; Antonietta, T.; Salvatorelli, L.; Kacerovská, D.; Kazakov, D.; Michal, M. Mammary and vaginal myofibroblastomas are genetically related lesions: Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis shows deletion of 13q14 region. Hum. Pathol. 2012, 43, 1887–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flucke, U.; van Krieken, J.H.; Mentzel, T. Cellular angiofibroma: Analysis of 25 cases emphasizing its relationship to spindle cell lipoma and mammary-type myofibroblastoma. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajiri, R.; Shiba, E.; Iwamura, R.; Kubo, C.; Nawata, A.; Harada, H.; Yoshino, K.; Hisaoka, M. Potential pathogenetic link between angiomyofibroblastoma and superficial myofibroblastoma in the female lower genital tract based on a novel MTG1-CYP2E1 fusion. Mod. Pathol. 2021, 34, 2222–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordaro, A.; Haynes, H.R.; Murigu, T.; Michal, M.; Maggiani, F.; Poyiatzis, D.; Palmer, A.; Melegh, Z. A report of a patient presenting with three metachronous 13q14LOH mesenchymal tumours: Spindle cell lipoma, cellular angiofibroma and mammary myofibroblastoma. Virchows Arch. 2021, 479, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, G. Stromal tumors of the lower female genital tract: Histogenetic, morphological and immunohistochemical similarities with the “benign spindle cell tumors of the mammary stroma”. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2007, 203, 827–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeper, T.A.; Rosai, J. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum. Report of nine cases of a distinctive type of gynecologic soft-tissue neoplasm. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1983, 7, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, M.R.; Bridge, J.A. Deep (aggressive) angiomyxoma. In WHO Classification of Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed.; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 266–267. [Google Scholar]

- Granter, S.R.; Nucci, M.R.; Fletcher, C.D. Aggressive angiomyxoma: Reappraisal of its relationship to angiomyofibroblastoma in a series of 16 cases. Histopathology 1997, 30, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetsch, J.F.; Laskin, W.B.; Lefkowitz, M.; Kindblom, L.G.; Meis-Kindblom, J.M. Aggressive angiomyxoma: A clinicopathologic study of 29 female patients. Cancer 1996, 78, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amezcua, C.A.; Begley, S.J.; Mata, N.; Felix, J.C.; Ballard, C.A. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female genital tract: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 12 cases. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2005, 15, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, G.; Angelico, G.; Michal, M.; Broggi, G.; Zannoni, G.F.; Covello, R.; Marletta, S.; Salvatorelli, L.; Parenti, R. The Wide Morphological Spectrum of Deep (Aggressive) Angiomyxoma of the Vulvo-Vaginal Region: A Clinicopathologic Study of 36 Cases, including Recurrent Tumors. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, F.; Erickson-Johnson, M.R.; Keeney, G.L.; Clayton, A.C.; Nascimento, A.G.; Wang, X.; Oliveira, A.M. Frequency and Characterization of HMGA2 and HMGA1 Rearrangements in Mesenchymal Tumors of the Lower Genital Tract. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2007, 46, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkness, R.; McCluggage, W.G. HMGA2 Is a Useful Marker of Vulvovaginal Aggressive Angiomyxoma but May Be Positive in Other Mesenchymal Lesions at This Site. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2021, 40, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucci, M.R.; Granter, S.R.; Fletcher, C.D. Cellular angiofibroma: A benign neoplasm distinct from angiomyofibroblastoma and spindle cell lipoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1997, 21, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ywasa, Y.; Fletcher, C.D.M.; Flucke, U. Cellular angiofibroma. In WHO Classification of Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed.; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Laskin, W.B.; Fetsch, J.F.; Mostofi, F.K. Angiomyofibroblastomalike tumor of the male genital tract: Analysis of 11 cases with comparison to female angiomyofibroblastoma and spindle cell lipoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1998, 22, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasa, Y.; Fletcher, C.D. Cellular angiofibroma: Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 51 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2004, 28, 1426–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCluggage, W.G.; Ganesan, R.; Hirschowitz, L.; Rollason, T.P. Cellular angiofibroma and related fibromatous lesions of the vulva: Report of a series of cases with a morphological spectrum wider than previously described. Histopathology 2004, 45, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiani, F.; Debiec-Rychter, M.; Vanbockrijck, M.; Sciot, R. Cellular angiofibroma: Another mesenchymal tumour with 13q14 involvement, suggesting a link with spindle cell lipoma and (extra)-mammary myofibroblastoma. Histopathology 2007, 51, 410–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Fletcher, C.D. Cellular angiofibroma with atypia or sarcomatous transformation: Clinicopathologic analysis of 13 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.C.; Mokánszki, A.; Huang, H.Y.; Geronimo Silva, R., Jr.; Chen, C.C.; Beke, L.; Mónus, A.; Méhes, G. First Glance of Molecular Profile of Atypical Cellular Angiofibroma/Cellular Angiofibroma with Sarcomatous Transformation by Next Generation Sequencing. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creytens, D. Cellular Angiofibroma with Sarcomatous Transformation Showing Pleomorphic Liposarcoma-Like and Atypical Lipomatous Tumor-Like Features. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2016, 38, 712–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCluggage, W.G.; Perenyei, M.; Irwin, S.T. Recurrent cellular angiofibroma of the vulva. J. Clin. Pathol. 2002, 55, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dargent, J.L.; de Saint Aubain, N.; Galdón, M.G.; Valaeys, V.; Cornut, P.; Noël, J.C. Cellular angiofibroma of the vulva: A clinicopathological study of two cases with documentation of some unusual features and review of the literature. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2003, 30, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, C.D.; Tsang, W.Y.; Fisher, C.; Lee, K.C.; Chan, J.K. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva. A benign neoplasm distinct from aggressive angiomyxoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1992, 16, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucci, M.R.; Fletcher, C.D. Vulvovaginal soft tissue tumours: Update and review. Histopathology 2000, 36, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, C.D.M. Angiomyofibroblastoma. In WHO Classification of Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours, 5th ed.; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, K.; Aadachi, K.; Saito, H. Huge pedunculated angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010 15, 201–205. [CrossRef]

- Omori, M.; Toyoda, H.; Hirai, T.; Ogino, T.; Okada, S. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva: A large pedunculated mass formation. Acta Med. Okayama 2006, 60, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Ockner, D.M.; Sayadi, H.; Swanson, P.E.; Ritter, J.H.; Wick, M.R. Genital angiomyofibroblastoma. Comparison with aggressive angiomyxoma and other myxoid neoplasms of skin and soft tissue. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1997, 107, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nasu, K.; Fujisawa, K.; Takai, N.; Miyakawa, I. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2002, 12, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perko, Z.; Durdov, M.G.; Druzijanić, N.; Kraljević, D.; Juricić, J. Giant Perianal Angiomyofibroblastoma—A Case Report. Coll. Antropol. 2006, 1, 243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Upreti, S.; Morine, A.; Ng, D.; Bigby, S.M. Lipomatous variant of angiomyofibroblastoma: A case report and review of the literature. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2015, 42, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, G.; Righi, A.; Caltabiano, R.; Casorzo, L.; Michal, M. Vulvovaginal angiomyofibroblastomas: Morphologic, immunohistochemical, and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis for deletion of 13q14 region. Hum. Pathol. 2014, 45, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, G.; Salvatorelli, L.; Angelico, G.; Vecchio, G.M.; Caltabiano, R. Lipomatous angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva: Diagnostic and histogenetic considerations. Pathologica 2014, 106, 322–326. [Google Scholar]

- Luis, P.P.; Quiñonez, E.; Nogales, F.F.; McCluggage, W.G. Lipomatous variant of angiomyofibroblastoma involving the vulva: Report of 3 cases of an extremely rare neoplasm with discussion of the differential diagnosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2015, 34, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nili, F.; Nicknejad, N.; Salarvand, S.; Akhavan, S. Lipomatous Angiomyofibroblastoma of the Vulva: Report of a Rare Variant. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2017, 36, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, G.P.; Young, R.H.; Dickersin, G.R.; Rosenberg, A.E. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva with sarcomatous transformation (“angiomyofibrosarcoma”). Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1997, 21, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folpe, A.L.; Tworek, J.A.; Weiss, S.W. Sarcomatous transformation in angiomyofibroblastomas: A clinicopathological, histological and immunohistochemical study of eleven cases. Mod. Pathol. 2001, 14, 12A. [Google Scholar]

- Barat, S.; TirgarTabari, S.; Shafaee, S. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the Vulva. Arch. Iran. Med. 2008, 11, 224–226. [Google Scholar]

- Laskin, W.B.; Fetsch, J.F.; Tavassoli, F.A. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the female genital tract: Analysis of 17 cases including a lipomatous variant. Hum. Pathol. 1997, 28, 1046–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, Y.; Shinkoh, Y.; Inai, K. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva: A mitotically active variant? Pathol. Int. 1998, 48, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukunaga, M.; Nomura, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Doi, K.; Endo, Y.; Ushigome, S. Vulval angiomyofibroblastoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of six cases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1997, 107, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Matsukuma, S.; Koga, A.; Suematsu, R.; Takeo, H.; Sato, K. Lipomatous angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva: A case report and review of the literature. Mol. Clin. Oncol/ 2017, 6, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, N.; Kawaguchi, M.; Koike, H.; Nishiyama, T.; Takahashi, K. Angiomyxoid tumor with an intermediate feature between cellular angiofibroma and angiomyofibroblastoma in the male inguinal region. Int. J. Urol. 2005, 12, 768–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, M.; Duc, C.; Ritz, S.; Bieri, S. Pelvic excision of large aggressive angiomyxoma in a woman: Irradiation for recurrent disease. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2006, 16 (Suppl. S1), 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskin, W.B.; Fetsch, J.F.; Tavassoli, F.A. Superficial cervicovaginal myofibroblastoma: Fourteen cases of a distinctive mesenchymal tumor arising from the specialized subepithelial stroma of the lower female genital tract. Hum. Pathol. 2001, 32, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, R.; McCluggage, W.G.; Hirschowitz, L.; Rollason, T.P. Superficial myofibroblastoma of the lower female genital tract: Report of a series including tumours with a vulval location. Histopathology 2005, 46, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, C.J.; Amanuel, B.; Brennan, B.A.; Jain, S.; Rajakaruna, R.; Wallace, S. Superficial cervico-vaginal myofibroblastoma: A report of five cases. Pathology 2005, 37, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, G.; Caltabiano, R.; Kacerovská, D.; Vecchio, G.M.; Kazakov, D.; Michal, M. Vulvovaginal myofibroblastoma: Expanding the morphological and immunohistochemical spectrum. A clinicopathologic study of 10 cases. Hum. Pathol. 2012, 43, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMenamin, M.E.; Fletcher, C.D. Mammary-type myofibroblastoma of soft tissue: A tumor closely related to spindle cell lipoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2001, 25, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howitt, B.E.; Fletcher, C.D. Mammary-type Myofibroblastoma: Clinicopathologic Characterization in a Series of 143 Cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2016, 40, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).