Ganglioneuroma of the Bladder in Association with Neurofibromatosis Type 1

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Justification of the Case Report

2. Case Report

2.1. History and Clinical Findings

2.2. Imaging Findings

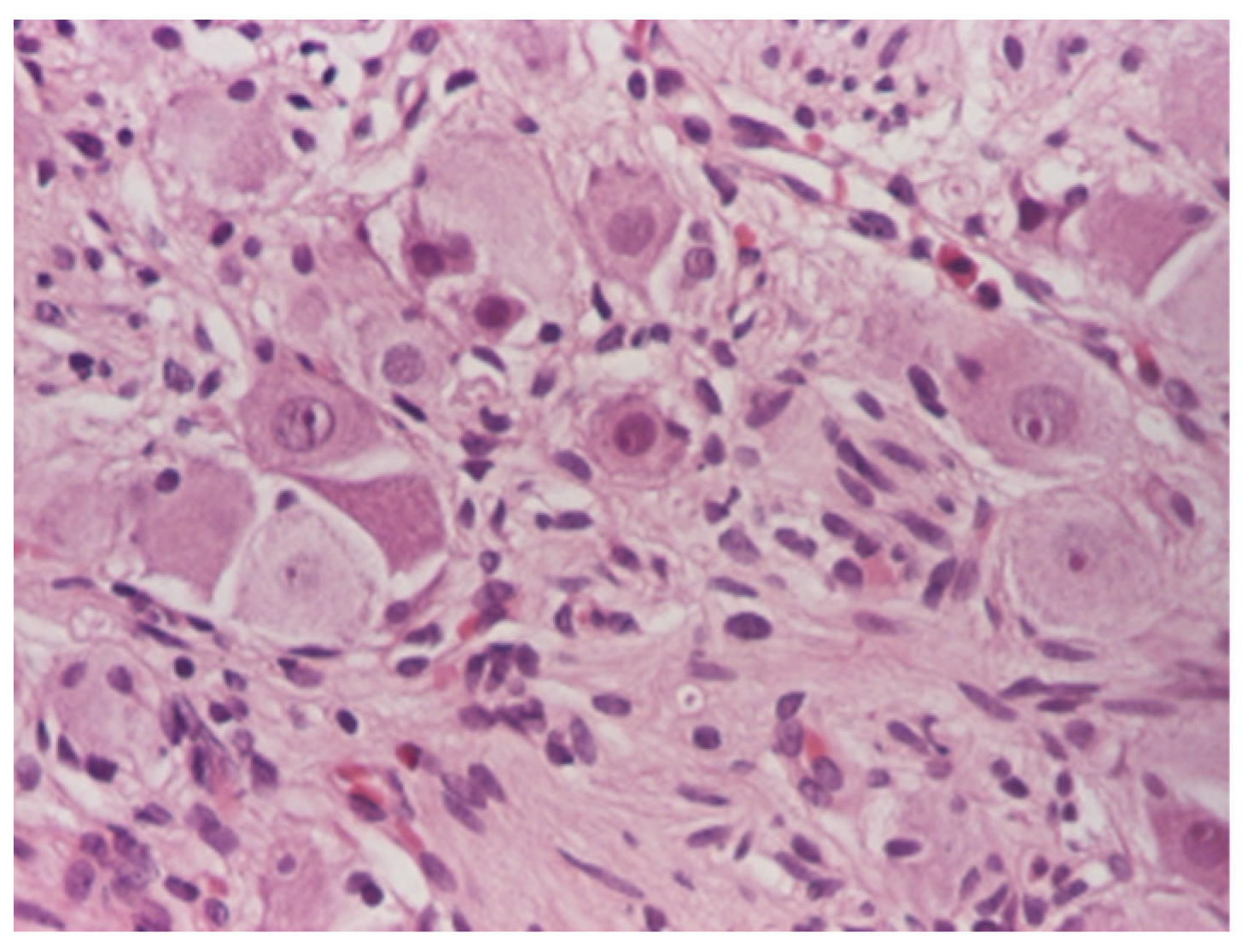

2.3. Operative and Pathological Findings

2.4. Follow-Up

3. Sources of Information

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scheithauer, B.W.; Santi, M.; Richter, E.R.; Belman, B.; Rushing, E.J. Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis and plexiform neurofibroma of the urinary bladder: Report of a pediatric example and literature review. Hum. Pathol. 2008, 39, 1708–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ure, I.; Gurocak, S.; Gönül, I.I.; Sozen, S.; Deniz, N. Neurofibromatosis Type 1 with Bladder Involvement. Case Rep. Urol. 2013, 2013, 145076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Legius, E.; Messiaen, L.; Wolkenstein, P.; Pancza, P.; Avery, R.A.; Berman, Y.; Blakeley, J.; Babovic-Vuksanovic, D.; Cunha, K.S.; Ferner, R.; et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neurofibromatosis type 1 and Legius syndrome: An international consensus recommendation. Genet Med. 2021, 23, 1506–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamatam, N.; Rayappan, E.; Smile, S.; Vivekanandan, R. Large ganglioneuroma presenting as presacral mass. BJR Case Rep. 2016, 2, 20150361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, C.; Williamson, A.K.; Friedman, A.A.; Palmer, L.S.; Fine, R.G. Bladder Ganglioneuroma in a 5-Year-old Girl Presenting With a Urinary Tract Infection and Hematuria: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Urology 2015, 85, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvitti, M.; Celestino, F.; Nappo, S.G.; Caione, P. Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis and plexiform neurofibroma of the urinary bladder: An uncommon cause of severe urological disease in an infant. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2013, 9, e131–e133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Jie, M.; Tao, Z.; Dongdong, X.; Yi, W.; Demao, D.; Lei, C.; Ci, Z.; Jiaxing, M.; Zhiqiang, Z.; et al. Ganglioneuroma with leiomyomatosis of the urinary bladder: A rare tumor causing frequent micturition and dysuria. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2014, 8, E44–E47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duceac, L.D.; Tarca, E.; Ciuhodaru, M.I.; Tantu, M.M.; Goroftei, R.E.B.; Banu, E.A.; Damir, D.; Glod, M.; Luca, A.C. Study on the Mechanism of Antibiotic Resistance. Rev. De Chim. 2019, 70, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiutiucă, R.C.; Pușcașu, A.I.N.; Țarcă, E.; Stoenescu, N.; Cojocaru, E.; Trandafir, L.M.; Țarcă, V.; Scripcariu, D.-V.; Moscalu, M. Urachal Carcinoma, An Unusual Possibility of Hematuria; Case Report and Literature Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, B.; Song, B.; Park, J.H.; Moon, K.C. Clinicopathologic Features of Benign Neurogenic Tumor of Urinary Bladder. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018, 26, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geoerger, B.; Hero, B.; Harms, D.; Grebe, J.; Scheidhauer, K.; Berthold, F. Metabolic activity and clinical features of primary ganglioneuromas. Cancer 2001, 91, 1905–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazzouz, M.H.; Hajjad, T.; Essatara, Y.; El Sayegh, H.; Iken, A.; Benslimane, L.; Nouini, Y. L’atteinte vésicale au cours de la neurofibromatose de Von Recklinghausen [The bladder involvement in Von Recklinghausen’s disease]. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014, 17, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, A.M.; Wolters, P.L.; Dombi, E.; Baldwin, A.; Whitcomb, P.; Fisher, M.J.; Weiss, B.; Kim, A.; Bornhorst, M.; Shah, A.C.; et al. Selumetinib in Children with Inoperable Plexiform Neurofibromas. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, A.M.; Glassberg, B.; Wolters, P.L.; Dombi, E.; Baldwin, A.; Fisher, M.J.; Kim, A.; Bornhorst, M.; Weiss, B.D.; O Blakeley, J.; et al. Selumetinib in children with neurofibromatosis type 1 and asymptomatic inoperable plexiform neurofibroma at risk for developing tumor-related morbidity. Neuro-Oncology 2022, 14, 1978–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.K.; Johnson, M.; Thornburg, L.; Halford, Z. A Review of Selumetinib in the Treatment of Neurofibromatosis Type 1–Related Plexiform Neurofibromas. Ann. Pharmacother. 2021, 56, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petracco, G.; Patriarca, C.; Spasciani, R.; Parafioriti, A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the bladder A case report. Pathologica 2019, 111, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A. A case of sarcoma of the urinary bladder in von Recklinghausen’s. Br. J. Urol. 1957, 29, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, S.R.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; MacLennan, G.T.; Montironi, R.; Cheng, L. Unique clinicopathologic and molecular characteristics of urinary bladder tumors in children and young adults. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2013, 31, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, S.; Balasubramanian, A.; Kao, C.-S.; Eisenberg, M.L.; Skinner, E.C. Co-Manifestations of Genital Neurofibromatosis in a Patient with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Urology 2020, 141, e49–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczkowska, M.; Callens, T.; Chen, Y.; Gomes, A.; Hicks, A.D.; Sharp, A.; Johns, E.; Uhas, K.A.; Armstrong, L.; Bosanko, K.A.; et al. Clinical spectrum of individuals with pathogenic NF1 missense variants affecting p.Met1149, p.Arg1276, and p.Lys1423: Genotype–phenotype study in neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum. Mutat. 2020, 41, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țarcă, V.; Țarcă, E.; Luca, F.-A. The Impact of the Main Negative Socio-Economic Factors on Female Fertility. Healthcare 2022, 10, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domon-Archambault, V.; Gagnon, L.; Benoit, A.; Perreault, S. Psychosocial Features of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 in Children and Adolescents. J. Child Neurol. 2018, 33, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ţarcă, E.; Cojocaru, E.; Trandafir, L.M.; Luca, A.C.; Melinte Popescu, A.S.; Butnariu, L.I.; Melinte Popescu, M.G.; Anton Păduraru, D.T.; Moscalu, M.; Rusu, D.; et al. Ganglioneuroma of the Bladder in Association with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12123126

Ţarcă E, Cojocaru E, Trandafir LM, Luca AC, Melinte Popescu AS, Butnariu LI, Melinte Popescu MG, Anton Păduraru DT, Moscalu M, Rusu D, et al. Ganglioneuroma of the Bladder in Association with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Diagnostics. 2022; 12(12):3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12123126

Chicago/Turabian StyleŢarcă, Elena, Elena Cojocaru, Laura Mihaela Trandafir, Alina Costina Luca, Alina Sinziana Melinte Popescu, Lăcrămioara Ionela Butnariu, Marian George Melinte Popescu, Dana Teodora Anton Păduraru, Mihaela Moscalu, Daniela Rusu, and et al. 2022. "Ganglioneuroma of the Bladder in Association with Neurofibromatosis Type 1" Diagnostics 12, no. 12: 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12123126

APA StyleŢarcă, E., Cojocaru, E., Trandafir, L. M., Luca, A. C., Melinte Popescu, A. S., Butnariu, L. I., Melinte Popescu, M. G., Anton Păduraru, D. T., Moscalu, M., Rusu, D., & Ţarcă, V. (2022). Ganglioneuroma of the Bladder in Association with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Diagnostics, 12(12), 3126. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12123126