Abstract

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDGs) are a heterogeneous group of disorders with impaired glycosylation of proteins and lipids. These conditions have multisystemic clinical manifestations, resulting in gradually progressive complications including skeletal involvement and reduced bone mineral density. Contrary to PMM2-CDG, all remaining CDG, including ALG12-CDG, ALG3-CDG, ALG9-CDG, ALG6-CDG, PGM3-CDG, CSGALNACT1-CDG, SLC35D1-CDG and TMEM-165, are characterized by well-defined skeletal dysplasia. In some of them, prenatal-onset severe skeletal dysplasia is observed associated with early death. Osteoporosis or osteopenia are frequently observed in all CDG types and are more pronounced in adults. Hormonal dysfunction, limited mobility and inadequate diet are common risk factors for reduced bone mineral density. Skeletal involvement in CDGs is underestimated and, thus, should always be carefully investigated and managed to prevent fractures and chronic pain. With the advent of new therapeutic developments for CDGs, the severity of skeletal complications may be reduced. This review focuses on possible mechanisms of skeletal manifestations, risk factors for osteoporosis, and bone markers in reported paediatric and adult CDG patients.

1. Introduction

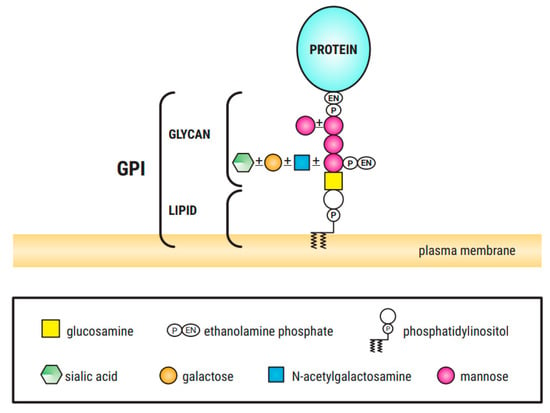

Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation (CDGs) are a clinically heterogenous group of over 150 diseases caused by defects in different steps of glycan metabolism pathways [1,2]. These genetic disorders are characterized by an impaired synthesis and attachment of glycans to glycoproteins and glycolipids, and impaired synthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) (Figure 1) [1]. These disorders are categorized into (a) protein N-glycosylation defects; (b) protein O-glycosylation defects; (c) glycolipid and GPI anchor synthesis defects and (d) multiple glycosylation pathways and other pathways defects [2].

Figure 1.

GPI structure, consisting of the conserved core glycan, phosphatidylinositol and glycan side chains ([3], own modification).

Among the different glycosylation defects, impaired protein N-glycosylation is the most common. Glycan processing (remodeling) takes place in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi apparatus [2]. O-glycosylation occurs in the Golgi apparatus and no lipid-linked intermediates are involved. In contrast to N-glycosylation, the process involves only the sequential addition of monosaccharides without remodeling [2,4]. Abnormalities in the synthesis of O-linked N-acetylglucosamine, galactose (Gal), mannose (Man), glucose (Glc) and fucose (Fuc) glycans have also been described [5]. GPI is a phosphoglyceride (Figure 1) that acts as a membrane anchor of proteins to the outer leaflet of the cellular membrane. GPI-anchor biosynthesis defects (GPI-BD) are categorized by an inappropriate GPI-anchors biosynthesis or modification (protein attachment, structural remodeling at both glycan and parts of GPI). Most of the CDGs have autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance, but autosomal dominant and X-linked forms have also been described. To date, about 80 different entities have been described in correlation with congenital disorder of glycosylation or CDG-like diseases. Although some genotype–phenotype correlation has been proposed, there is a significant phenotypic variability within the same genotype.

Glycosylation is key for a variety of posttranslational biological processes including main components of the hormone cascades regulating growth and metabolism [5,6]. As a result, CDG patients present with very diverse clinical phenotypes, with multi-system involvement [4,5,6,7]. These include cognitive impairment, neurological (epilepsy, hypotonia, ataxia and polyneuropathy), ophthalmological, skeletal, cardiac, hepatic, haematological and endocrinological phenotypes [1,2,7,8].

The mechanisms of bone disease in CDGs seem to be multifactorial. Malabsorption and liver dysfunction lead to a poor nutritional state which impacts the growth hormone-insulin–like growth factor (GH/IGF) axis and results in a short stature [9,10]. Given that patients with CDGs manifest their skeletal abnormalities in childhood, one may speculate that they are attributed to the impaired glycosylation in the bone tissue in the early stages of life.

So far, there have been no therapies targeting specific organ such as eye, kidney, heart, muscles or skeleton, with only supportive management being available [10].

This review describes skeletal manifestations and bone mineral density abnormalities in paediatric and adult CDG patients with the aim to discuss the heterogeneity of clinical manifestations and correlate the genetic data (causative genes) with observed skeletal phenotype to evaluate the potential mechanism of mutational effect on the phenotype.

2. Skeletal Abnormalities

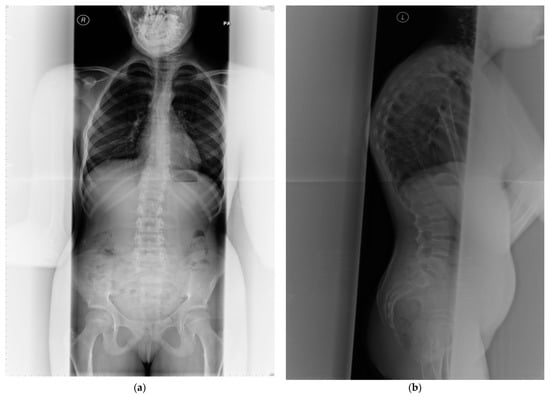

2.1. Skeletal Characteristics of PMM2-CDG

PMM2-CDG is the most prevalent disorder of abnormal glycosylation of N-linked oligosaccharides leading to endocrine abnormalities including dysfunction of IGFBP3 and an acid-labile subunit in the IGF pathway which result in short stature [11]. Growth failure is commonly observed in children with PMM2-CDG [7,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Despite normal serum calcium, phosphate and magnesium concentrations, osteopenia/osteoporosis are frequently demonstrated in this condition since childhood (Table 1) [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Skeletal abnormalities are common, although under-diagnosed [17], often leading to kypho/scoliosis, severe spinal cord deformity and vertebral compression fractures [7] (see Figure 2). Regular orthopaedic assessment and intervention are required if scoliosis becomes evident, with cervical spine x-rays in neutral, flexion, and extension to assess for atlantoaxial instability. Fractures are common and appear to heal normally. Skeletal dysplasia is not a typical feature of PMM2-CDG but has been reported before (Table 1 and Table 2). Joint contractures are relatively common and affect patients’ quality of life.

Table 1.

Skeletal phenotype in various CDG types.

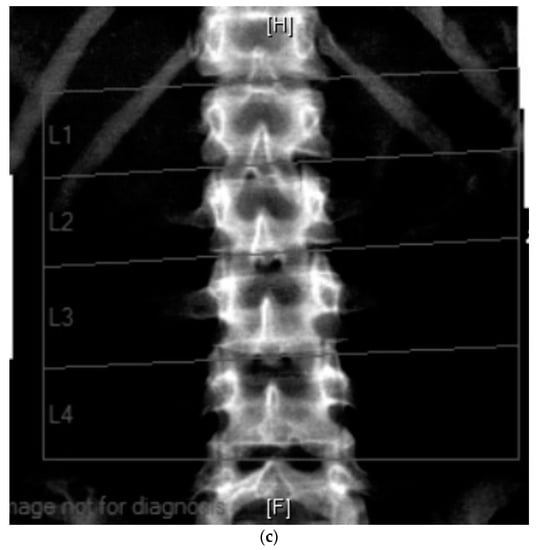

Figure 2.

(a) Anterior posterior view—whole spine x-ray in a 25-year-old female patient affected with PMM2-CDG; bone mineral density is below expected for her age (T score −2.6, z-score −2.6); (b) lateral view; (c) radiological features of her lumbar spine: there is a double mild curve scoliosis and no rotational deformity. All pedicles are visualized. There is impression of slight upper hyperkyphosis and impression of multilevel Schmorl’s nodes.

Table 2.

Review of published cases of Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation who developed skeletal and bone mineral density abnormalities and their genotypes (abbreviations: n.a.—not analysed; Pt—patient; pc—percentile).

2.2. Skeletal Dysplasia in Other CDGs

Contrary to PMM2-CDG, skeletal dysplasia was well characterized in other CDGs, including ALG12-CDG, ALG3-CDG, ALG9-CDG, ALG6-CDG, PGM3-CDG, CSGALNACT1-CDG, SLC35D1-CDG and TMEM165-CDG (Table 1).

The combination of features observed in patients with ALG12-CDG, including interphalangeal dislocations, talipes equinovarus, rhizomelic limb shortening, midface hypoplasia, short metacarpals, and a horizontal acetabular roof, resembled the features of pseudodiastrophic dysplasia (Table 1) [21,22]. Pseudodiastrophic dysplasia (264180) is characterized by rhizomelic shortening of the limbs and severe clubfoot deformity, in association with elbow and proximal interphalangeal joint dislocations, platyspondyly, and scoliosis [23,24,25].

The features of patients with ALG9-CDG reported by Tham et al. were similar to those reported by Gillessen-Kaesbach and Nishimura and to some extent overlapping with those of individuals with ALG3-CDG and ALG12-CDG (Table 1 and 2) [27,28,29,30].

Most patients affected with PGM3-CDG showed skeletal abnormalities (Table 1 and Table 2). Scoliosis has been reported as the mildest manifestation of the PGM3-related skeletal phenotype [33]. Two patients described by Stray-Pedersen et al. (2014) presented with a recognizable skeletal dysplasia resembling Desbuquois dysplasia (#251450) [34]. This condition is an autosomal recessive osteochondrodysplasia characterized by severe prenatal and postnatal growth retardation (stature less than −5 SD), short extremities (rhizomelic and mesomelic shortening), shortened tubular bones with metaphyseal flaring, an exaggerated trochanter minor of the proximal femur (monkey-wrench malformation), advanced bone age, joint laxity, and progressive kyphoscoliosis (Table 2) [35,36].

2.3. Joint and Cartilage Involvement in CDG

In two patients with typical Schneckenbecken dysplasia (# 269250), Rautengarten et al. found biallelic mutations in both alleles of SLC35D1 (Table 1 and Table 2) [43]. Schneckenbecken dysplasia (#269250) is a perinatally lethal skeletal dysplasia characterized by the distinctive, snail-like appearance of the ilia, thoracic hypoplasia, severe flattening of the vertebral bodies and short, thick long bones [44].

Among genes implicated in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), biallelic mutations in B4GALT7 (encoding galactosyltransferase-I) have been described in patients affected with the progeroid form of EDS presenting with radioulnar synostosis, diffuse osteopenia, splaying of the ribs, broad thumbs and long fingers, long and overriding toes, equinovarus deformities, single palmar crease, and hypermobile joints (Table 1 and Table 2) [45,46,47,48].

Short stature, generalized osteopenia/osteoporosis and epi- and metaphyseal dysplasia were reported in patients with TMEM165-CDG (Table 1) [6,50].

2.4. GPI-Biosynthesis Defects (GPI-BD)

Defects in the glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) biosynthesis pathway have unique skeletal manifestations. GPI-anchor biosynthesis can be divided into the synthesis stage (responsible genes: DPM1, DPM2, DPM3, MPDU1, PIGA, PIGB, PIGC, PIGF, PIGG, PIGH, PIGL, PIGM, PIGN, PIGO, PIGP, PIGQ, PIGV, PIGW, PIGX, PIGY) and the transamidase + remodelling stage (responsible genes: GPA1, MPPE1, PGAP1, PGAP2, PGAP3, PIGK, PIGS, PIGT, PIGU) [51]. Abnormal digit morphology, absent distal phalanges, aplasia/hypoplasia of fingers, short digit, broad finger and broad toe, clubbing, and clinodactyly were more frequently observed in the synthesis group (Table 1) [52,53,54,55,56,57]. On the other hand, osteopenia was more frequently observed in the transamidase + remodelling group [53].

Brachytelephalangy was consistently found in all the reported PIGV-CDG patients (Table 2) [52]. It was also found in most of the reported patients with PIGO-CDG (Hyperphosphatasia with mental retardation syndrome 2, HPMRS2, #614749) [58,59]. This skeletal finding could lead to the suspicion of Coffin-Siris syndrome given the neurological findings in both syndromes, i.e., delayed psychomotor development, hypotonia and expressive language delay. Coffin-Siris syndrome in its typical form (CSS1, #135900) characterized by aplasia or hypoplasia of the distal phalanx and hypoplastic, aplastic nails (even absent fifth fingernail in some patients), developmental or cognitive delay of varying degree, distinctive facial features, hypotonia, hirsutism/hypertrichosis, and congenital malformations of the cardiac, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and/or central nervous systems [60].

2.5. Genotype–Phenotype Correlation

The genetic background of CDG is highly variable and includes various genes. In Table 2, we report the clinical and molecular findings of CDG patients with skeletal abnormalities. Most of patients were compound heterozygotes for autosomal recessive hypomorphic mutations and homozygotes are rather sporadic or family related cases. It is difficult to draw any strong conclusions regarding the possible genotype–phenotype correlation in such a heterogenic group.

For patients with homozygous mutations, we were able to give some conclusions regarding, i.e., CSGALNACT1 and SLC35D1 genes. Knockout of the orthologous mouse CSGALNACT1 indicates that the protein is necessary for normal cartilage development and aggrecan metabolism [61]. Mutations in CSGALNACT1 are associated with a mild skeletal dysplasia and joint laxity [41]. The clinical significance of the described variant c.791A > G (p.Asn264Ser) is defined as likely pathogenic.

Hiraoka et al. created Slc35d1-deficient mice that present with a lethal form of skeletal dysplasia (severe shortening of limbs and facial structures) with short, sparse chondroitin sulphate chains caused by a defect in chondroitin sulphate biosynthesis [62]. Epiphyseal cartilage in these homozygous mutant mice showed a decreased proliferating zone with round chondrocytes, scarce matrices and reduced proteoglycan aggregates. Variant c.125delA in SLC35D1 was reported only once, and its significance has been defined as pathogenic (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/RCV000001182, accessed on 27 June 2021).

Skeletal and/or bone mineral density abnormalities are common features of all CDG types. Osteoporosis and/or osteopenia, growth failure, skeletal dysplasia and joint abnormalities were described (Table 1 and Table 2). Genotype–phenotype correlation is impossible due to gene heterogeneity, diversity of individual markers and compound heterozygosity in most described cases (Table 2).

Contrary to PMM2-CDG, skeletal abnormalities are well characterized in other CDG. There is a group of CDGs, including ALG12-CDG, ALG3-CDG, ALG9-CDG, ALG6-CDG, PGM3-CDG, CSGALNACT1-CDG, SLC35D1-CDG, and TMEM-165 with well-defined skeletal dysplasia. In some of them (ALG12-CDG, ALG3-CDG, ALG9-CDG, PGM3-CDG, SLC35D1-CDG), a severe prenatal-onset skeletal dysplasia was observed and associated with an early death. Among them, ALG12-CDG, ALG3-CDG and ALG9-CDG represent distinct entities involved in primary lipid-linked oligosaccharide (LLO) synthesis. These three mannosyltransferases function in direct sequential order, adding mannose moieties to LLO. On the other hand, phosphoglucomutase 3 (PGM3) is required for the biosynthesis of uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc), a precursor for both N-linked and O-linked glycosylated proteins. These facts could explain the severe phenotype of reported skeletal abnormalities.

Glycosylation is essential for proteins involved in the development of cartilage and bone and in skeletal patterning pathways. Two of the glycosylation defects, TMEM165-CDG and CSGALNACT1-CDG, are characterized by skeletal dysplasia and abnormal cartilage development. It has been also observed in an experimental study by Bammens et al. (2015), that the TMEM165-deficient zebrafish model exhibited phenotypic patterns of bone dysplasia and abnormal cartilage development similar to the major clinical findings reported in three patients with a homozygous splice mutation [63].

Two other CDGs, CSGALNACT1-CDG and SLC35D1-CDG, are caused by defects in genes responsible for glycosaminoglycans biosynthesis.

CSGalNAcT1 (chondroitin sulphate N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-1) gene codes the CSGalNAcT-1 protein that is the main enzyme in the biosynthesis of sulphated glycosaminoglycans chondroitin and dermatan sulphate in cartilage [42]. Biallelic loss-of-function mutations in CSGALNACT1 gene results in reduced CSGalNAcT-1 activity leading to altered levels of chondroitin, dermatan, and heparan sulphate and cause a mild skeletal dysplasia with joint laxity and advanced bone age, CSGALNACT1-CDG [42].

Another gene, SLC35D1 gene, encodes the protein that transports substrates needed for glucuronidation and chondroitin sulphate biosynthesis [62]. The protein resides in the endoplasmic reticulum, and transports both UDP-glucuronic acid and UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine from the cytoplasm to the endoplasmic reticulum. In humans, loss of function mutation in this gene cause Schneckenbecken dysplasia associated with perinatal lethal skeletal dysplasias [62].

2.6. Risk Factors for Osteoporosis in CDGs

Hormonal dysfunction, resulting from hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism, is a risk factor for reduced bone mineral density in females with CDGs [7,64,65]. It requires treatment with oestrogen to avoid osteoporosis; however, it increases the risk of thrombotic events and must be dosed carefully.

Gastrointestinal problems and malabsorption may lead to hypovitaminosis D. It is therefore worth considering screening for common causes of chronically decreased vitamin D such as celiac disease [65].

Bone deformities and chronic pain result in limited mobility and wheelchair use. Low BMI and disuse sarcopenia are frequent clinical features of patients with CDGs and, in the long term, they may cause low bone mineral density and recurrent fractures.

2.7. Bone Markers

Historically, this GPI-linked enzyme, has been used to assign glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis defects (GPI-BD) to the phenotypic group termed hyperphosphatasia with mental retardation syndrome (HPMRS) and to distinguish them from another subset of GPI-BD—multiple congenital anomalies hypotonia seizures syndrome (MCAHS) [51]. However, with the increasing number of individuals diagnosed with a GPI-BD, hyperphosphatasia has been shown to be a variable feature and not more useful for GPI-BD distinguishing.

Bone-specific alkaline phosphatase activity measured in serum is an indicator of osteoblastic activity.

Serum and urinary deoxypyridinoline and pyridinoline, cross-linking amino acids that stabilize collagen chains within the extracellular matrix, can also be measured when screening for reduced bone mineral density in PMM2-CDG disorders [10]. Bone markers of formation (P1NP) or resorption (CTX) measurement in CDGs requires further clinical studies to better understand what factors are likely to affect their concentration in these conditions. All the bone markers should be interpreted in the context of symptoms, age, gender, limited physical activity including wheelchair use, and diet.

Transferrin glycosylation has been the main biomarker for CDG screening and monitoring of the response to treatment. The analysis of protein N-glycosylation profile is widely used in CDGs and other conditions [66].

There is a scope for using N-glycans in monitoring of bone disease progression and further research is warranted to confirm the preliminary findings [67].

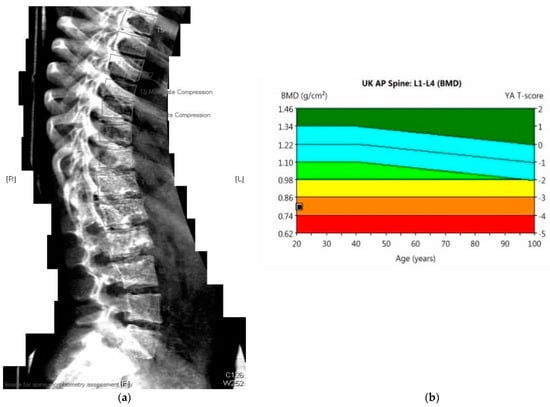

The effectiveness of supportive management can be evaluated by DEXA scan (Figure 3), a gold standard method for monitoring the progression of bone mineral density decline. The whole spine x-ray (Figure 2) can be used for identification of bone deformities and fractures. QCT however is the sensitive quantitative method used to assess the bone mineral density. Body composition has become increasingly utilized in Inherited Metabolic Disorders field and provides additional information about the bone and muscle involvement.

Figure 3.

(a) 23-year-old male with PMM2-CDG (BMI 17 kg/m2). DEXA scan: Results: bone mineral density below expected range for age. Evidence of moderate compression at T8 and T9 vertebrae. (b) DEXA scan: Lumbar spine (L1–L4): T-score −3.5, Z-score −3.5, bone mineral density 0.8 g/cm3.

Importantly, a multidisciplinary approach with pain specialist, rheumatologist, endocrinologist, metabolic specialist, physiotherapist and dietician is key to successful management of bone health in this group of disorders.

2.8. Therapies and Bone Health

Some CDG types including PGM1-CDG and TMEM165-CDG, characterized by an undergalactosylation of the N-glycans have shown good responses to galactose supplementation [68,69]. Additionally, deficient import of UDP-Gal into the ER or the Golgi, required by β1,4-galactosyltransferase to elongate the growing glycan chain, has been documented in SLC35A2-CDG [70]. Although in this condition, galactose supplementation has improved glycosylation, it has not been clear whether it has had an impact on clinical manifestations of the disease including bones anomalies [70]. Apart from galactose, mannose has been utilized as a therapy in MPI-CDG [9,10] and has been shown to restore endocrine function and coagulation and alleviates enteropathy, but does not always reverse progressive hepatic involvement [71]. The long-term effect of mannose on skeletal outcomes needs careful attention. As a result of the UDP-fucose transporter defect and impaired fucosylation in the Golgi in SLC35C1-CDG, patients affected with this CDG type have been benefited from fucose supplementation [72,73]. A decreased infection rates and improved expression of E- and P-selectin ligands and restored neutrophil numbers have been documented [72,73].

Although biochemical and haematological parameters improved with these therapeutic approaches, the impact on bone tissue remains unclear. Long-term prospective observational studies will elucidate whether the bone health in CDGs improves with the nutritional supplementation and/or new therapeutic approaches including pharmacological chaperone, antisense or gene therapies (discussed in detail in [9,10]).

3. Conclusions

CDGs should be considered as a differential diagnosis of skeletal dysplasia, especially in multiorgan and systemic involvement. It is particularly important for CDGs with prenatal-onset skeletal dysplasia which is associated with severe clinical outcomes. Thus, early diagnosis is key to family genetic counselling.

Skeletal involvement in CDGs is underestimated and thus should be more carefully investigated and managed shortly after a diagnosis is made. In adult CDG patients screening for additional risk factors for osteoporosis should be considered. There is a scope for utilizing bone markers in monitoring of the bone tissue dynamics. The anticipated expansion in the therapeutic strategies is hoped to impact the bone health in CDGs and prevent skeletal complications.

Author Contributions

Project administration: P.L., A.T.-S., A.J.-S.; Investigation: P.L., K.M.S., E.C., A.T.-S., A.J.-S.; Supervision: A.T.-S., A.J.-S.; Writing—original draft: P.L.; Writing—review and editing: P.L., K.M.S., E.C., A.T.-S., A.J.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by the Children’s Memorial Health Institute intramural grant S190/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Number 23/KBE/2020, Warsaw, Poland.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ALG3 | alpha-1,3-mannosyltransferase; |

| ALG6 | alpha-1,3-glucosyltransferase; |

| ALG9 | alpha-1,2-mannosyltransferase; |

| ALG12 | alpha-1,6-mannosyltransferase; |

| CDGs | congenital disorders of glycosylation; |

| COG | component of oligomeric Golgi complex; |

| CSGalNAcT1 | chondroitin sulphate N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-1; |

| EDS | Ehlers-Danlos syndrome; |

| GPI | glycosylphosphatidylinositol; |

| GPI-BD | glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis defects; |

| LLO | lipid-linked oligosaccharide; |

| PGM3 | phosphoglucomutase 3; |

| PMM2 | phosphomannomutase 2; |

| SLC35D1 | UDP-glucuronic acid/UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine transporter; |

| TMEM165 | transmembrane protein 165. |

References

- Péanne, R.; de Lonlay, P.; Foulquier, F.; Kornak, U.; Lefeber, D.J.; Morava, E.; Pérez, B.; Seta, N.; Thiel, C.; Van Schaftingen, E.; et al. Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG): Quo vadis? Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2018, 61, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, R.; Marques-Da-Silva, D.; Brasil, S.A.; Pascoal, C.; Ferreira, V.D.R.; Morava, E.; Jaeken, J. The challenge of CDG diagnosis. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 126, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, T. Biosynthesis and biology of mammalian GPI-anchored proteins. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 190290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brasil, S.; Pascoal, C.; Francisco, R.; Marques-Da-Silva, D.; Andreotti, G.; Videira, P.A.; Morava, E.; Jaeken, J.; Ferreira, V.D.R. CDG Therapies: From bench to bedside. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abu Bakar, N.; Lefeber, D.J.; van Scherpenzeel, M. Clinical glycomics for the diagnosis of congenital disorders of glycosylation. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018, 41, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zeevaert, R.; De Zegher, F.; Sturiale, L.; Garozzo, D.; Smet, M.-H.; Moens, M.; Matthijs, G.; Jaeken, J. Bone dysplasia as a key feature in three patients with a novel congenital disorder of glycosylation (CDG) type ii due to a deep intronic splice mutation in TMEM165. JIMD Rep. Case Res. Rep. 2012, 8, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coman, D.; Bostock, D.; Hunter, M.; Kannu, P.; Irving, M.; Mayne, V.; Fietz, M.; Jaeken, J.; Savarirayan, R. Primary skeletal dysplasia as a major manifesting feature in an infant with congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ia. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2008, 146, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, M.; Roda, C.; Monin, M.L.; Arion, A.; Barth, M.; Bednarek, N.; Bidet, M.; Bloch, C.; Boddaert, N.; Borgel, D.; et al. Clinical, laboratory and molecular findings and long-term follow-up data in 96 French patients with PMM2-CDG (phosphomannomutase 2-congenital disorder of glycosylation) and review of the literature. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 54, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witters, P.; Cassiman, D.; Morava, E. Nutritional therapies in congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG). Nutrients 2017, 9, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verheijen, J.; Tahata, S.; Kozicz, T.; Witters, P.; Morava, E. Therapeutic approaches in congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) involving N-linked glycosylation: An update. Genet. Med. 2019, 22, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altassan, R.; Péanne, R.; Jaeken, J.; Barone, R.; Bidet, M.; Borgel, D.; Brasil, S.; Cassiman, D.; Cechova, A.; Coman, D.; et al. International clinical guidelines for the management of phosphomannomutase 2-congenital disorders of glycosylation: Diagnosis, treatment and follow up. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kjaergaard, S.; Müller, J.; Skovby, F. Prepubertal growth in congenital disorder of glycosylation type Ia (CDG-Ia). Arch. Dis. Child. 2002, 87, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monin, M.-L.; Mignot, C.; De Lonlay, P.; Héron, B.; Masurel, A.; Mathieu-Dramard, M.; Lenaerts, C.; Thauvin, C.; Gérard, M.; Roze, E.; et al. 29 French adult patients with PMM2-congenital disorder of glycosylation: Outcome of the classical pediatric phenotype and depiction of a late-onset phenotype. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witters, P.; Honzik, T.; Bauchart, E.; Altassan, R.; Pascreau, T.; Bruneel, A.; Vuillaumier, S.; Seta, N.; Borgel, D.; Matthijs, G.; et al. Long-term follow-up in PMM2-CDG: Are we ready to start treatment trials? Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.; Duffy, M.; Sarafoglou, K. rhIGF-1 therapy for growth failure and IGF-1 deficiency in congenital disorder of glycosylation ia (PMM2 Deficiency). Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2010, 20, 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnewich, D.; O’Brien, K.; Sparks, S. Clinical features in adults with congenital disorders of glycosylation type Ia (CDG-Ia). Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2007, 145, 302–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, R.; Pavone, V.; Pennisi, P.; Fiumara, A.; Fiore, C.E. Assessment of skeletal status in patients with congenital disorder of glycosylation type IA. Int. J. Tissue React. 2002, 24, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garel, C.; Baumann, C.; Besnard, M.; Ogier, H.; Jaeken, J.; Hassan, M. Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome type I: A new cause of dysostosis multiplex. Skelet. Radiol. 1998, 27, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyskens, F.; Ceuterick, C.; Martin, J.-J.; Janssens, G.; Jaeken, J. Carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndrome with previously unreported features. Acta Paediatr. 1994, 83, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, P.T.; Winchester, B.G.; Keir, G. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy in a neonate with the carbohydrate-defi-cient glycoprotein syndrome. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 1992, 15, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, C.; Basinger, A.A.; Güçsavaş-Çalıkoğlu, M.; Sun, L.; Powell, C.M.; Henderson, F.W.; Aylsworth, A.S.; Freeze, H. Expanding spectrum of congenital disorder of glycosylation Ig (CDG-Ig): Sibs with a unique skeletal dysplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, cardiomyopathy, genital malformations, and early lethality. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2007, 143, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murali, C.; Lu, J.T.; Jain, M.; Liu, D.S.; Lachman, R.; Gibbs, R.A.; Lee, B.H.; Cohn, D.; Campeau, P.M. Diagnosis of ALG12-CDG by exome sequencing in a case of severe skeletal dysplasia. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2014, 1, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eteson, D.J.; Beluffi, G.; Burgio, G.; Belloni, C.; Lachman, R.S.; Rimoin, D.L. Pseudodiastrophic dysplasia: A distinct newborn skeletal dysplasia. J. Pediatr. 1986, 109, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, A.B.; Mizumoto, S.; Arts, P.; Yap, P.; Feng, J.; Schreiber, A.; Babic, M.; King-Smith, S.L.; Barnett, C.P.; Moore, L.; et al. Pseudodiastrophic dysplasia expands the known phenotypic spectrum of defects in proteoglycan biosynthesis. J. Med. Genet. 2020, 57, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yap, P.; Liebelt, J.E.; Amor, D.J.; Moore, L.; Savarirayan, R. Pseudodiastrophic dysplasia: Two cases delineating and expanding the pre and postnatal phenotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2016, 170, 1363–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepais, L.; Cheillan, D.; Frachon, S.C.; Hays, S.; Matthijs, G.; Panagiotakaki, E.; Abel, C.; Edery, P.; Rossi, M. ALG3-CDG: Report of two siblings with antenatal features carrying homozygous p.Gly96Arg mutation. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2015, 167, 2748–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillessen-Kaesbach, G.; Meinecke, P.; Garrett, C.; Padberg, B.C.; Rehder, H.; Passarge, E. New autosomal recessive lethal disorder with polycystic kidneys type Potter I, characteristic face, microcephaly, brachymelia, and congenital heart defects. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1993, 45, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, G.; Nakayama, M.; Fuke, Y.; Suehara, N. A lethal osteochondrodysplasia with mesomelic brachymelia, round pelvis, and congenital hepatic fibrosis: Two siblings born to consanguineous parents. Pediatr. Radiol. 1998, 28, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, E.; Eklund, E.A.; Hammarsjö, A.; Bengtson, P.; Geiberger, S.; Lagerstedt-Robinson, K.; Malmgren, H.; Nilsson, D.; Grigelionis, G.; Conner, P.; et al. A novel phenotype in N-glycosylation disorders: Gillessen-Kaesbach-Nishimura skeletal dysplasia due to path-ogenic variants in ALG9. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AlSubhi, S.; Alhashem, A.; Alazami, A.; Tlili, K.; Alshahwan, S.; Lefeber, D.; Alkuraya, F.S.; Tabarki, B.; Baumgartner, M.; Patterson, M.; et al. Further delineation of the ALG9-CDG phenotype. JIMD Rep. 2015, 27, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drijvers, J.M.; Lefeber, D.J.; de Munnik, S.A.; Pfundt, R.; van de Leeuw, N.; Marcelis, C.; Thiel, C.; Koerner, C.; Wevers, R.A.; Morava, E. Skeletal dysplasia with brachytelephalangy in a patient with a congenital disorder of glycosylation due to ALG6 gene mutations. Clin. Genet. 2010, 77, 507–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Eklund, E.A.; Van Hove, J.L.; Freeze, H.H.; Thomas, J.A. Clinical and molecular characterization of the first adult con-genital disorder of glycosylation (CDG) type Ic patient. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2005, 137, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, A.; Lazaroski, S.; Wu, G.; Haslam, S.M.; Fliegauf, M.; Mellouli, F.; Patiroglu, T.; Unal, E.; Ozdemir, M.A.; Jouhadi, Z.; et al. Hypomorphic homozygous mutations in phosphoglucomutase 3 (PGM3) impair immunity and increase serum IgE levels. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stray-Pedersen, A.; Backe, P.H.; Sorte, H.S.; Mørkrid, L.; Chokshi, N.Y.; Erichsen, H.C.; Gambin, T.; Elgstøen, K.B.; Bjørås, M.; Wlodarski, M.W. PGM3 mutations cause a congenital disorder of glycosylation with severe im-munodeficiency and skeletal dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 95, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inoue, S.; Ishii, A.; Shirotani, G.; Tsutsumi, M.; Ohta, E.; Nakamura, M.; Mori, T.; Inoue, T.; Nishimura, G.; Ogawa, A.; et al. Case of desbuquois dysplasia type 1: Potentially lethal skeletal dysplasia. Pediatr. Int. 2014, 56, e26–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco-Cuéllar, G.; Gauthier, J.; Désilets, V.; Lachance, C.; Lemire-Girard, M.; Rypens, F.; Le Deist, F.; Decaluwe, H.; Duval, M.; Soglio, D.B.-D.; et al. A novel PGM3 mutation is associated with a severe phenotype of bone marrow failure, severe combined immunodeficiency, skeletal dysplasia, and congenital malformations. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2017, 32, 1853–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morava, E.; Zeevaert, R.; Korsch, E.; Huijben, K.; Wopereis, S.; Matthijs, G.; Keymolen, K.; Lefeber, D.J.; De Meirleir, L.; Wevers, R.A. A common mutation in the COG7 gene with a consistent phenotype including microcephaly, adducted thumbs, growth retar-dation, VSD and episodes of hyperthermia. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 15, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Steet, R.A.; Bohorov, O.; Bakker, J.A.; Newell, J.; Krieger, M.; Spaapen, L.; Kornfeld, S.; Freeze, H.H. Mutation of the COG complex subunit gene COG7 causes a lethal congenital disorder. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulquier, F.; Vasile, E.; Schollen, E.; Callewaert, N.; Raemaekers, T.; Quelhas, D.; Jaeken, J.; Mills, P.; Winchester, B.; Krieger, M.; et al. Conserved oligomeric golgi complex subunit 1 deficiency reveals a previously uncharacterized con-genital disorder of glycosylation type II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 3764–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foulquier, F.; Ungar, D.; Reynders, E.; Zeevaert, R.; Mills, P.; García-Silva, M.T.; Briones, P.; Winchester, B.; Morelle, W.; Krieger, M.; et al. A new inborn error of glycosylation due to a Cog8 deficiency reveals a critical role for the Cog1–Cog8 interaction in COG complex formation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vodopiutz, J.; Mizumoto, S.; Lausch, E.; Rossi, A.; Unger, S.; Janocha, N.; Costantini, R.; Seidl, R.; Greber-Platzer, S.; Yamada, S.; et al. Chondroitin sulfateN-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-1 (CSGalNAcT-1) deficiency results in a mild skeletal dysplasia and joint laxity. Hum. Mutat. 2016, 38, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizumoto, S.; Janecke, A.R.; Sadeghpour, A.; Povysil, G.; McDonald, M.T.; Unger, S.; Greber-Platzer, S.; Deak, K.L.; Katsanis, N.; Superti-Furga, A.; et al. CSGALNACT1-congenital disorder of glycosylation: A mild skeletal dysplasia with advanced bone age. Hum. Mutat. 2019, 41, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rautengarten, C.; Quarrell, O.W.; Stals, K.; Caswell, R.C.; De Franco, E.; Baple, E.; Burgess, N.; Jokhi, R.; Heazlewood, J.L.; Offiah, A.C.; et al. A hypomorphic allele of SLC35D1 results in Schneckenbecken-like dysplasia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 3543–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikkels, P.G.; Stigter, R.H.; Knol, I.E.; van der Harten, H.J. Schneckenbecken dysplasia, radiology, and histology. Pediatr. Radiol. 2001, 31, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faiyaz-Ul-Haque, M.; Zaidi, S.H.; Al-Ali, M.; Al-Mureikhi, M.S.; Kennedy, S.; Al-Thani, G.; Tsui, L.C.; Teebi, A.S. A novel missense mutation in the galactosyltransferase-I (B4GALT7) gene in a family exhibiting facioskeletal anomalies and Ehlers-Danlos syn-drome resembling the progeroid type. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2004, 128, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, H.; Rosthøj, S.; Quentin, E.; Hollmann, J.; Glössl, J.; Okada, S.; Tønnesen, T. Glycosaminoglycan-free small proteoglycan core protein is secreted by fibroblasts from a patient with a syndrome resembling progeroid. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1987, 41, 436–453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baasanjav, S.; Al-Gazali, L.; Hashiguchi, T.; Mizumoto, S.; Fischer-Zirnsak, B.; Horn, D.; Seelow, D.; Ali, B.R.; Aziz, S.A.; Langer, R.; et al. Faulty initiation of proteoglycan synthesis causes cardiac and joint defects. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 89, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seidler, D.G.; Faiyaz-Ul-Haque, M.; Hansen, U.; Yip, G.W.; Zaidi, S.H.; Teebi, A.S.; Kiesel, L.; Götte, M. Defective glycosylation of decorin and biglycan, altered collagen structure, and abnormal phenotype of the skin fibroblasts of an Ehlers-Danlos syndrome patient carrying the novel Arg270Cys substitution in galactosyltransferase I (beta4GalT-7). J. Mol. Med. 2006, 84, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritelli, M.; Cinquina, V.; Giacopuzzi, E.; Venturini, M.; Chiarelli, N.; Colombi, M. Further defining the phenotypic spectrum of B3GAT3 mutations and literature review on linkeropathy syndromes. Genes 2019, 10, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foulquier, F.; Amyere, M.; Jaeken, J.; Zeevaert, R.; Schollen, E.; Race, V.; Bammens, R.; Morelle, W.; Rosnoblet, C.; Legrand, D.; et al. TMEM165 deficiency causes a congenital disorder of glycosylation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 91, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carmody, L.C.; Blau, H.; Danis, D.; Zhang, X.A.; Gourdine, J.P.; Vasilevsky, N.; Krawitz, P.; Thompson, M.D.; Robinson, P.N. Significantly different clinical phenotypes associated with mutations in synthesis and transamidase+remodeling glycosylphosphati-dylinositol (GPI)-anchor biosynthesis genes. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horn, D.; Krawitz, P.; Mannhardt, A.; Korenke, G.C.; Meinecke, P. Hyperphosphatasia-mental retardation syndrome due to PIGV mutations: Expanded clinical spectrum. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2011, 155, 1917–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altassan, R.; Fox, S.; Poulin, C.; Buhas, D. Hyperphosphatasia with mental retardation syndrome, expanded phenotype of PIGL related disorders. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2018, 15, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabe, P.; Haverkamp, F.; Emons, D.; Rosskamp, R.; Zerres, K.; Passarge, E. Syndrome of developmental retardation, facial and skeletal anomalies, and hyperphosphatasia in two sisters: Nosology and genetics of the coffin-siris syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1991, 41, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelis, C.L.; Rieu, P.; Beemer, F.; Brunner, H.G. Severe mental retardation, epilepsy, anal anomalies, and distal phalangeal hypoplasia in siblings. Clin. Dysmorphol. 2007, 16, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, D.; Schottmann, G.; Meinecke, P. Hyperphosphatasia with mental retardation, brachytelephalangy, and a distinct facial gestalt: Delineation of a recognizable syndrome. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 53, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.D.; Nezarati, M.M.; Gillessen-Kaesbach, G.; Meinecke, P.; Mendoza, R.; Mornet, E.; Brun-Heath, I.; Squarcioni, C.P.; Legeai-Mallet, L.; Munnich, A.; et al. Hyperphosphatasia with seizures, neurologic deficit, and characteristic facial features: Five new patients with Mabry syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2010, 52, 1661–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawitz, P.; Murakami, Y.; Hecht, J.; Krüger, U.; Holder, S.E.; Mortier, G.; Chiaie, B.D.; De Baere, E.; Thompson, M.D.; Roscioli, T.; et al. Mutations in PIGO, a member of the GPI-anchor-synthesis pathway, cause hyperphosphatasia with mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 91, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morren, M.-A.; Jaeken, J.; Visser, G.; Salles, I.; Van Geet, C.; BioResource, N.; Simeoni, I.; Turro, E.; Freson, K. PIGO deficiency: Palmoplantar keratoderma and novel mutations. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schrier Vergano, S.; Santen, G.; Wieczorek, D.; Wollnik, B.; Matsumoto, N.; Deardorff, M.A. Coffin-Siris Syndrome; Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Stephens, K., Amemiya, A., Eds.; GeneReviews: Seattle, WA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Gulberti, S.; Jacquinet, J.-C.; Chabel, M.; Ramalanjaona, N.; Magdalou, J.; Netter, P.; Coughtrie, M.W.H.; Ouzzine, M.; Fournel-Gigleux, S. Chondroitin sulfate N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase-1 (CSGalNAcT-1) involved in chondroitin sulfate initiation: Impact of sulfation on activity and specificity. Glycobiology 2011, 22, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hiraoka, S.; Furuichi, T.; Nishimura, G.; Shibata, S.; Yanagishita, M.; Rimoin, D.L.; Superti-Furga, A.; Nikkels, P.G.; Ogawa, M.; Katsuyama, K.; et al. Nucleotide-sugar transporter SLC35D1 is critical to chondroitin sulfate synthesis in cartilage and skeletal development in mouse and human. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1363–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bammens, R.; Mehta, N.; Race, V.; Foulquier, F.; Jaeken, J.; Tiemeyer, M.; Steet, R.; Matthijs, G.; Flanagan-Steet, H. Abnormal cartilage development and altered N-glycosylation in Tmem165-deficient zebrafish mirrors the phenotypes associated with TMEM165-CDG. Glycobiology 2015, 25, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stepien, K.M. Hormonal dysfunction in adult patients affected with inherited metabolic disorders. J. Mother Child 2020, 24, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Noman, K.; Hendriksz, C.; Radcliffe, G.; Roncaroli, F.; Moreea, S.; Hussain, A.; Stepien, K.M. Clinical outcomes in an adult patient with mannose phosphate isomerase-congenital disorder of glycosylation who discontinued mannose therapy. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2020, 25, 100646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colhoun, H.O.; Treacy, E.P.; MacMahon, M.; Rudd, P.M.; FitzGibbon, M.; O’Flaherty, R.; Stepien, K.M. Validation of an automated ultraperformance liquid chromatography IgG N-glycan analytical method applicable to classical galactosaemia. Ann. Clin. Biochem. Int. J. Lab. Med. 2018, 55, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepien, K.M.; Colhoun, H.O.; Gautsch, M.; Rubio-Gozalbo, M.E.; Dawson, C.; Lambert, D.; O’Flaherty, R.; Doran, P.; Treacy, E. Reduced bone density in classical galactosaemia, is abnormal glycosylation a factor? Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018, 123, 267–268. [Google Scholar]

- Morelle, W.; Potelle, S.; Witters, P.; Wong, S.; Climer, L.; Lupashin, V.; Matthijs, G.; Gadomski, T.; Jaeken, J.; Cassiman, D.; et al. Galactose supplementation in patients with TMEM165-CDG rescues the glycosylation defects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Radenkovic, S.; Bird, M.J.; Emmerzaal, T.L.; Wong, S.Y.; Felgueira, C.; Stiers, K.M.; Sabbagh, L.; Himmelreich, N.; Poschet, G.; Wind-molders, P.; et al. The metabolic map into the pathomechanism and treatment of PGM1-CDG. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 104, 835–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dörre, K.; Olczak, M.; Wada, Y.; Sosicka, P.; Grüneberg, M.; Reunert, J.; Kurlemann, G.; Fiedler, B.; Biskup, S.; Hörtnagel, K.; et al. A new case of UDP-galactose transporter deficiency (SLC35A2-CDG): Molecular basis, clinical phenotype, and therapeutic approach. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2015, 38, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mention, K.; Lacaille, F.; Valayannopoulos, V.; Romano, S.; Kuster, A.; Cretz, M.; Zaidan, H.; Galmiche, L.; Jaubert, F.; De Keyzer, Y.; et al. Development of liver disease despite mannose treatment in two patients with CDG-Ib. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008, 93, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, T.; Lühn, K.; Srikrishna, G.; Freeze, H.H.; Harms, E.; Vestweber, D. Correction of leukocyte adhesion deficiency type II with oral fucose. Blood 1999, 94, 3976–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagdas, D.; Yılmaz, M.; Kandemir, N.; Tezcan, I.; Etzioni, A.; Sanal, Ö. A novel mutation in leukocyte adhesion deficiency type II/CDGIIc. J. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 34, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).