From Nutcracker Phenomenon to Nutcracker Syndrome: A Pictorial Review

Abstract

1. Background

2. Definition

3. Epidemiology

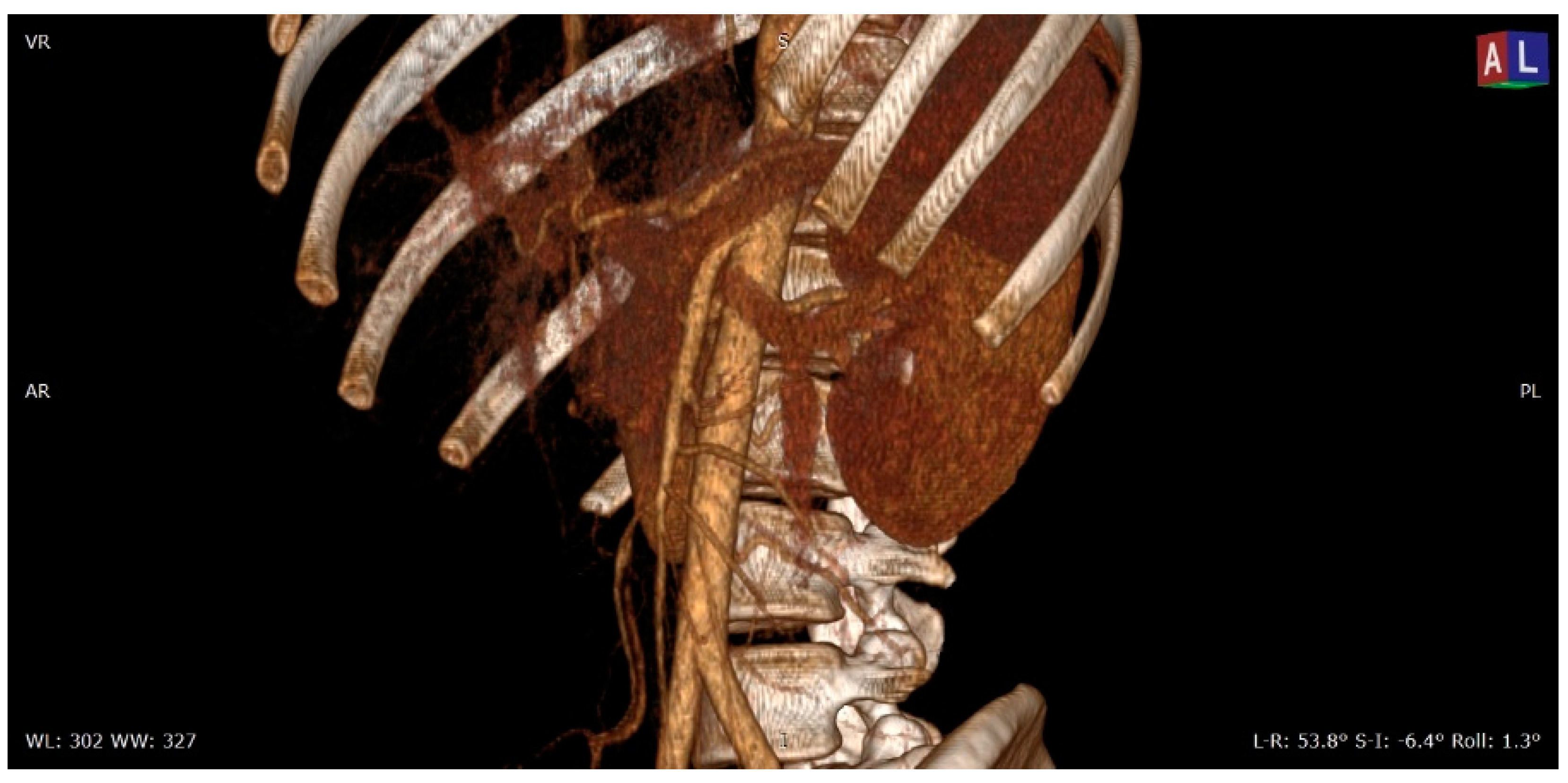

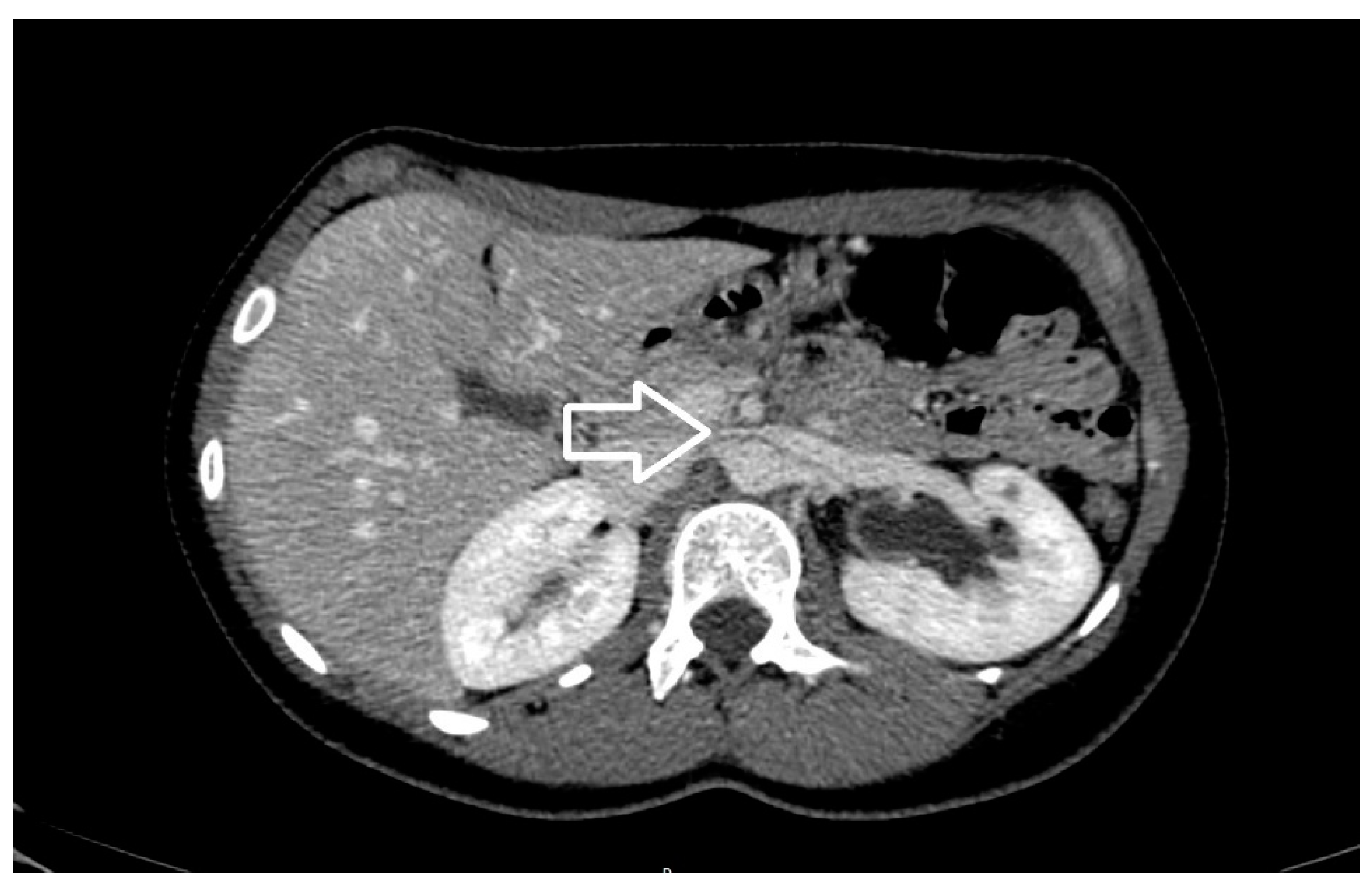

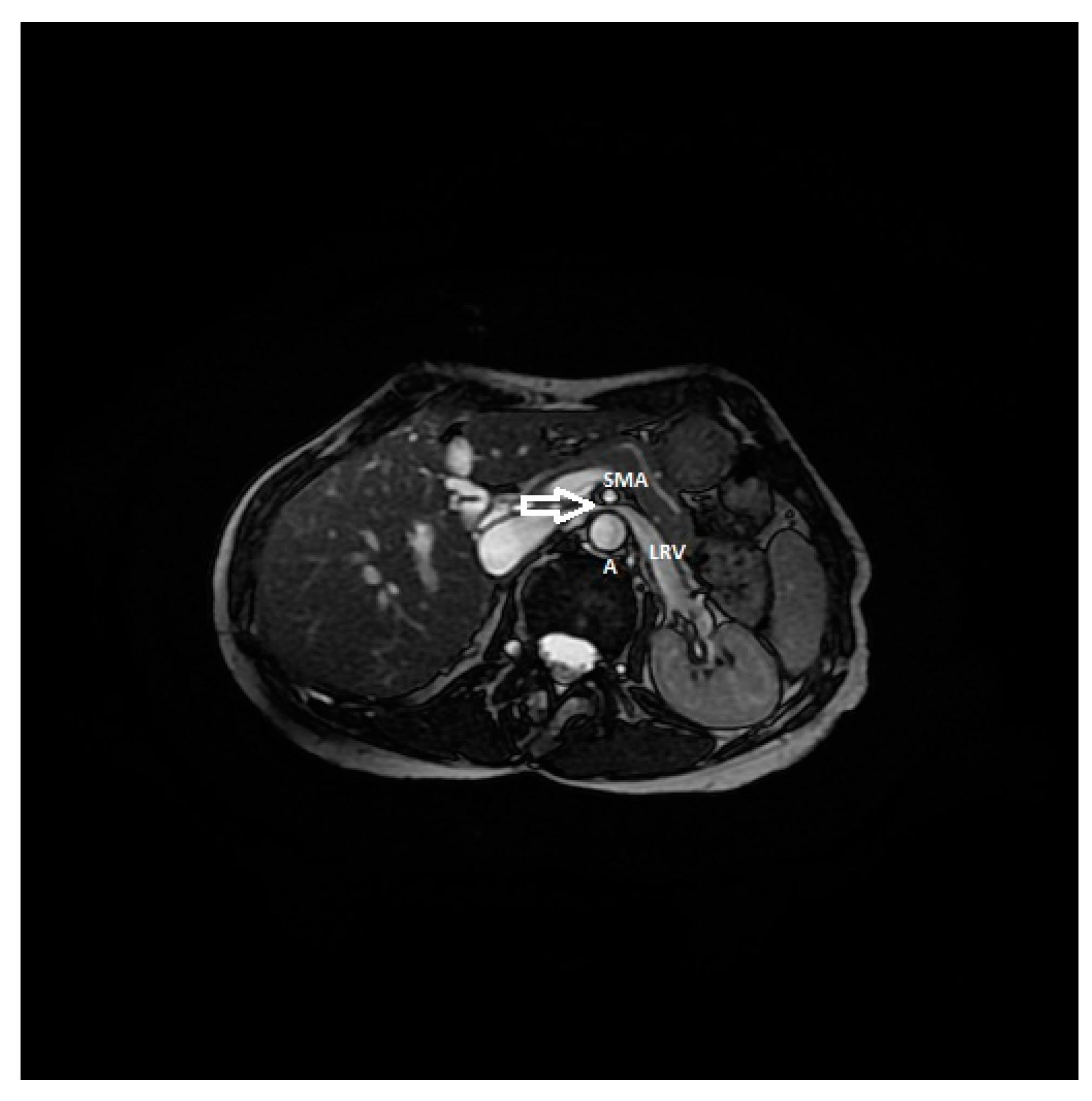

4. Pathogenesis and Mechanism of LRV Entrapment

5. Clinical Features Suspicious for NS

6. Diagnostic Criteria for NP

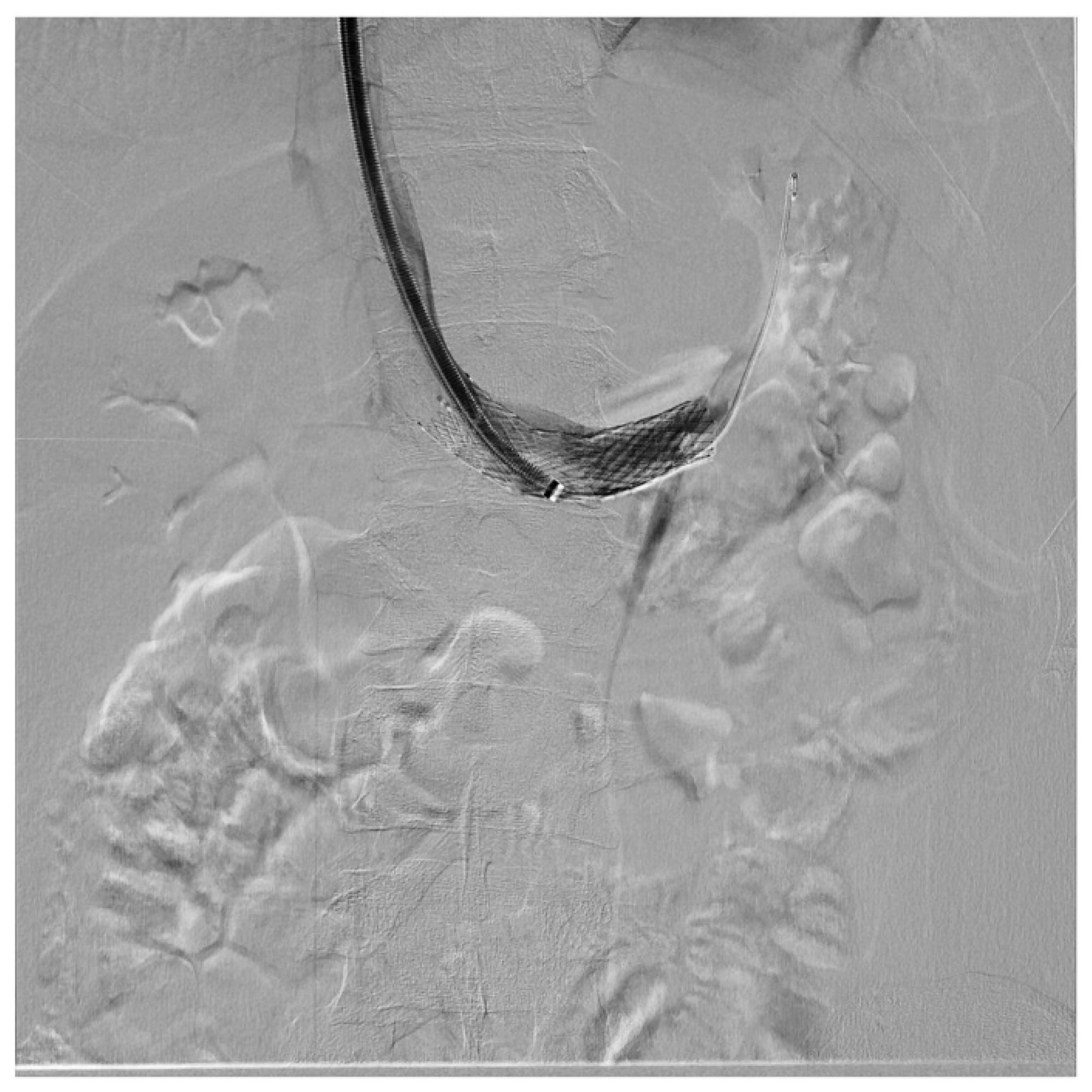

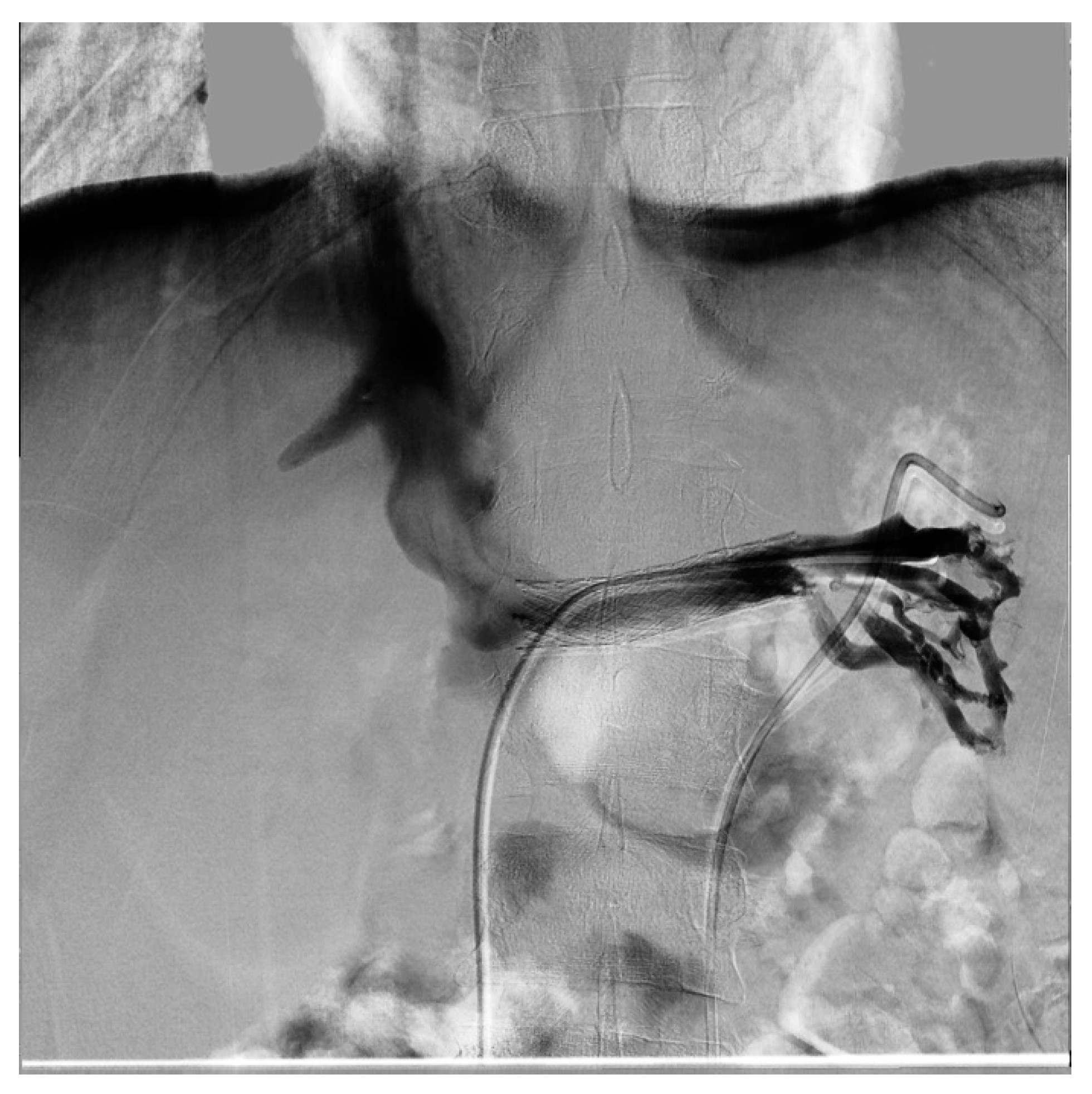

7. Treatment

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMA | aortomesenteric angle |

| CIV | common iliac vein |

| ECD-US | eco-color Doppler |

| IVC | inferior vena cava |

| IVUS | intravascular ultrasound |

| LRV | left renal vein |

| MALS | median arcuate ligament syndrome |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| NS | nutcracker syndrome |

| NP | nutcracker phenomenon |

| OVS | ovarian vein syndrome |

| PV | peak velocities |

| RAS-I | angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors |

| SMA | superior mesenteric artery |

| TC | computed tomography |

| UPJ | uretero-pelvic junction |

| US | ultrasound |

References

- Lamba, R.; Tanner, D.; Sekhon, S.; McGahan, J.; Corwin, M.; Lall, C. Multidetector CT of vascular compression syndromes in the abdomen and pelvis. Radiographics 2014, 34, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliahou, R.; Sosna, J.; Bloom, A.I. Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Clinical and Imaging Features of Vascular Compression Syndromes. Radiographics 2012, 32, E33–E49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurklinsky, A.K.; Rooke, T.W. Nutcracker Phenomenon and Nutcracker Syndrome. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.I.; Lee, J.S. Nutcracker phenomenon or nutcracker syndrome? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2005, 20, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, C.; Isard, H.J. Left renal vein entrapment: A new diagnostic finding in retroperitoneal disease. Radiology 1969, 92, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, R.W.; Fleisher, H.L., III; Redman, J.F.; Smith, J.W.; Harshfield, D.L.; Ferris, E.J. Mesoaortic compression of the left renal vein (the so-called nutcracker syndrome): Repair by a new stenting procedure. J. Vasc. Surg. 1988, 8, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.J.; Lee, J.M.; Nam, D.H.; Ryu, J.K.; Lee, S.H. Discriminating renal nutcracker syndrome from asymptomatic nutcracker phenomenon using multidetector computed tomography. Abdom. Radiol. (NY) 2016, 41, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.C.B. Method of Anatomy; Baltimore, M.D., Ed.; Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1937; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr, A.R.; Mina, E. Anatomical and surgical aspects in the operative management of varicocele. Urol. Cutan. Rev. 1950, 54, 257–262. [Google Scholar]

- Schepper, A. “Nutcracker” phenomenon of the renal vein and venous pathology of the left kidney. J. Belge. Radiol. 1972, 55, 507–511. [Google Scholar]

- Chait, A.; Matasar, K.W.; Fabian, C.E.; Mellins, H.Z. Vascular Impressions on the Ureters. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1971, 111, 729–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsukura, H.; Arai, M.; Miyawaki, T. Nutcracker phenomenon in two siblings of a Japanese family. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2004, 20, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ananthan, K.; Onida, S.; Davies, A. Nutcracker Syndrome: An Update on Current Diagnostic Criteria and Management Guidelines. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2017, 53, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanji, A.; Malcolm, P.; Karim, M. Nutcracker Syndrome and Radiographic Evaluation of Loin Pain and Hematuria. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 55, 1142–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.I.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, M.-J. The Prevalence, Physical Characteristics and Diagnosis of Nutcracker Syndrome. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2006, 32, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Tian, L.; Li, D.; Li, M.; Jin, W.; Zhang, H. Nutcracker syndrome—How well do we know it? Urology 2014, 83, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polguj, M.; Topol, M.; Majos, A. An unusual case of left venous renal entrapment syndrome: A new type of nutcracker phenomenon? Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2013, 35, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.L.T.; Lo, R.; Chan, F.L.; Wong, K.K. The posterior ‘‘nutcracker’’: Hematuria secondary to retroaortic left renal vein. Urology 1986, 20, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, A.; Tsetis, D.; Calcara, G.; Figuera, M.; Coppolino, F.; Patti, M.T.; Midiri, M.; Granata, A. Nutcracker Syndrome Due to Left Renal Vein Compression by an Aberrant Right Renal Artery. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2007, 50, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaper, K.R.L.; Jackson, J.E.; Williams, G. The nutcracker syndrome: An uncommon cause of haematuria. Br. J. Urol. 1994, 74, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatkin, N.; Morozov, A.; Lopatkina, L. Essential Renal Haemorrhages. Eur. Urol. 1978, 4, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, S.; Bumpus, K.; Kapadia, S.R.; Gray, B.; Lyden, S.; Shishehbor, M.H. The Nutcracker Syndrome. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 25, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marone, E.M.; Psacharopulo, D.; Tshomba, Y.; Chiesa, R. A typical case of nutcracker phenomenon. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011, 53, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, S.K.; Oliveira, G.R.; Rosovsky, R.P. An easily missed diagnosis: Flank pain and nutcracker syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2013, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scultetus, A.H.; Villavicencio, J.; Gillespie, D.L. The nutcracker syndrome: Its role in the pelvic venous disorders. J. Vasc. Surg. 2001, 34, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosotani, Y.; Kiyomoto, H.; Fujioka, H.; Takahashi, N.; Kohno, M. The nutcracker phenomenon accompanied by renin-dependent hypertension. Am. J. Med. 2003, 114, 617–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, A.; Clementi, A.; Floccari, F.; Di Lullo, L.; Basile, A. An unusual case of posterior nutcracker syndrome. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2014, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrett, N.D.; Wilson, R.B.; Cosman, P.; Biankin, A.V. Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome: Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2008, 13, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inal, M.; Bilgili, K.M.Y.; Sahin, S. Nutcracker syndrome accompanying pelvic congestion syndrome; Color Doppler sonography and multislice CT findings: A case report. Iran. J. Radiol. 2014, 11, e11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Jin, W.; San, P.; Xu, P.; Pan, S. The Left Renal Entrapment Syndrome: Diagnosis and Treatment. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2007, 21, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, M.B.; Bilgici, C.M.; Hayalioglu, E. Anterior and posterior nutcracker syndrome accompanying left circumaortic renal vein in an adolescent: Case report. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2016, 114, e114–e116. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, J.-E.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, I.-O.; Kim, S.H.; Yeon, K.M.; Ha, I.S.; Cheong, H.I.; Choi, Y. Nutcracker syndrome in children with gross haematuria: Doppler sonographic evaluation of the left renal vein. Pediatr. Radiol. 2006, 36, 682–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poyraz, A.K.; Firdolas, F.; Onur, M.R.; Kocakoç, E. Evaluation of left renal vein entrapment using multidetector computed tomography. Acta Radiol. 2013, 54, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beinart, C.; Sniderman, K.W.; Tamura, S.; Vaughan, E.D.; Sos, T.A. Left Renal Vein to Inferior Vena Cava Pressure Relationship in Humans. J. Urol. 1982, 127, 1070–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, N.R.; Kalra, M.; Bower, T.C.; Vrtiska, T.J.; Ricotta, J.J.; Gloviczki, P. Left renal vein transposition for nutcracker syndrome. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 49, 386–394. discussion 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenfellner, M.; Steinbach, F.; Schultz-Lampel, D.; Schantzen, W.; Walter, K.; Cramer, B.; Thüroff, J. The Nutcracker Syndrome: New Aspects of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Urol. 1991, 146, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Sampath, R.; Khan, M.S. Current trends in the diagnosis and management of renal nutcracker syndrome: A review. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2006, 31, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgerinos, E.D.; McEnaney, R.; A Chaer, R. Surgical and endovascular interventions for nutcracker syndrome. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 2013, 26, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, L.F.; Saguia, S.L.d.N.; Migueli, C.A.D.; Perin, M.A.d.C.; Lorrete, F.L.; Santana, N.P.; Chervin, E.L.N.; Singishalli, L.A.S.; Gimenez, M.P. Young woman with nutcracker syndrome without main clinic manifestation: Hematuria-Case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2017, 31, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.-S.; Lee, E.-J. ACE inhibition can improve orthostatic proteinuria associated with nutcracker syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2006, 21, 1765–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeik, N.; Gloviczki, P.; Macedo, T.A. Posterior Nutcracker Syndrome. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2011, 45, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, M.T. Nutcracker syndrome: When should it be treated and how? Perspect. Vasc. Surg. Endovasc. Ther. 2009, 21, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullery, B.W.; Itoga, N.K.; Mell, M.W. Transposition of the Left Renal Vein for the Treatment of Nutcracker Syndrome in Children: A Short-term Experience. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2014, 28, 1938.e5–1938.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neste, M.G.; Narasimham, D.L.; Belcher, K.K. Endovascular Stent Placement as a Treatment for Renal Venous Hypertension. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 1996, 7, 859–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yi, L.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Rao, J.; Liu, L.; Yang, J. Diagnosis and Surgical Treatment of Nutcracker Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience. Urology 2009, 73, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, O.; Grisoli, D.; Boufi, M.; Marani, I.; Hakam, Z.; Barthelemy, P.; Alimi, Y.S. Endovascular stenting in the treatment of pelvic vein congestion caused by nutcracker syndrome: Lessons learned from the first five cases. J. Vasc. Surg. 2005, 42, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, A.; Tsetis, D.; Calcara, G.; Figuera, M.; Patti, M.T.; Ettorre, G.C.; Granata, A. Percutaneous Nitinol Stent Implantation in the Treatment of Nutcracker Syndrome in Young Adults. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2007, 18, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jing, T.; Qin, J.; Xia, D.; Wang, S. Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Transposition of the Left Renal Vein for Treatment of the Nutcracker Syndrome. Urology 2015, 86, e27–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policha, A.; Lamparello, P.J.; Sadek, M.; Berland, T.; Maldonado, T. Endovascular Treatment of Nutcracker Syndrome. Ann. Vasc. Surg. 2016, 36, 295.e1–295.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Kim, C.W.; Kim, S.; Lee, T.H.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, S.H.; Jeong, Y.S. Long-Term follow-Up after endovascular stent placement for treatment of nutcracker syndrome. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2005, 16, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.; Beech, A.; Braithwaite, B. Transperitoneal Laparoscopic Left Gonadal Vein Ligation Can Be the Right Treatment Option for Pelvic Congestion Symptoms Secondary to Nutcracker Syndrome. Vascular 2007, 15, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criterion | Instrumental Examination Technique | Reference Values Compatible with the Diagnosis of NP | References |

|---|---|---|---|

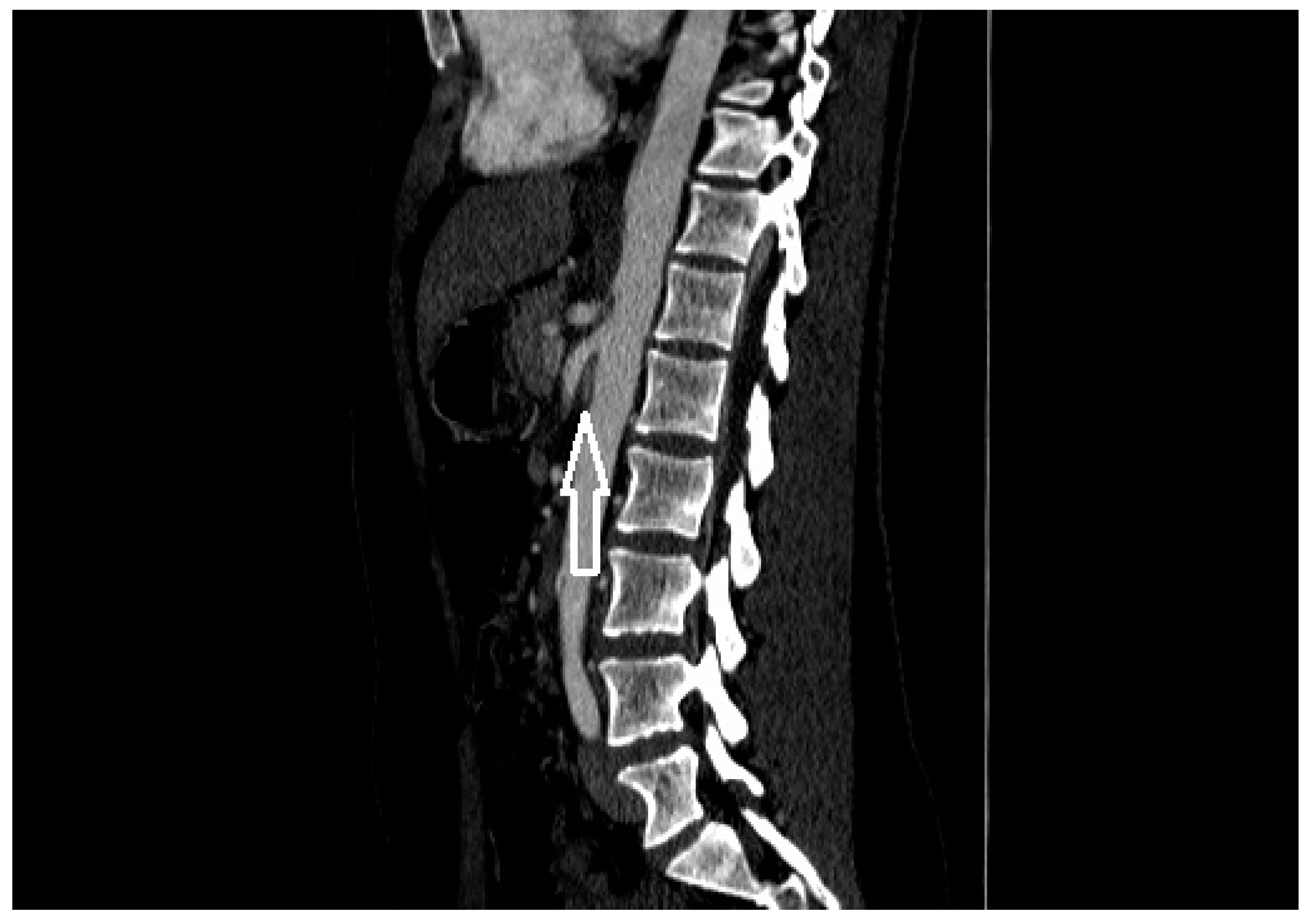

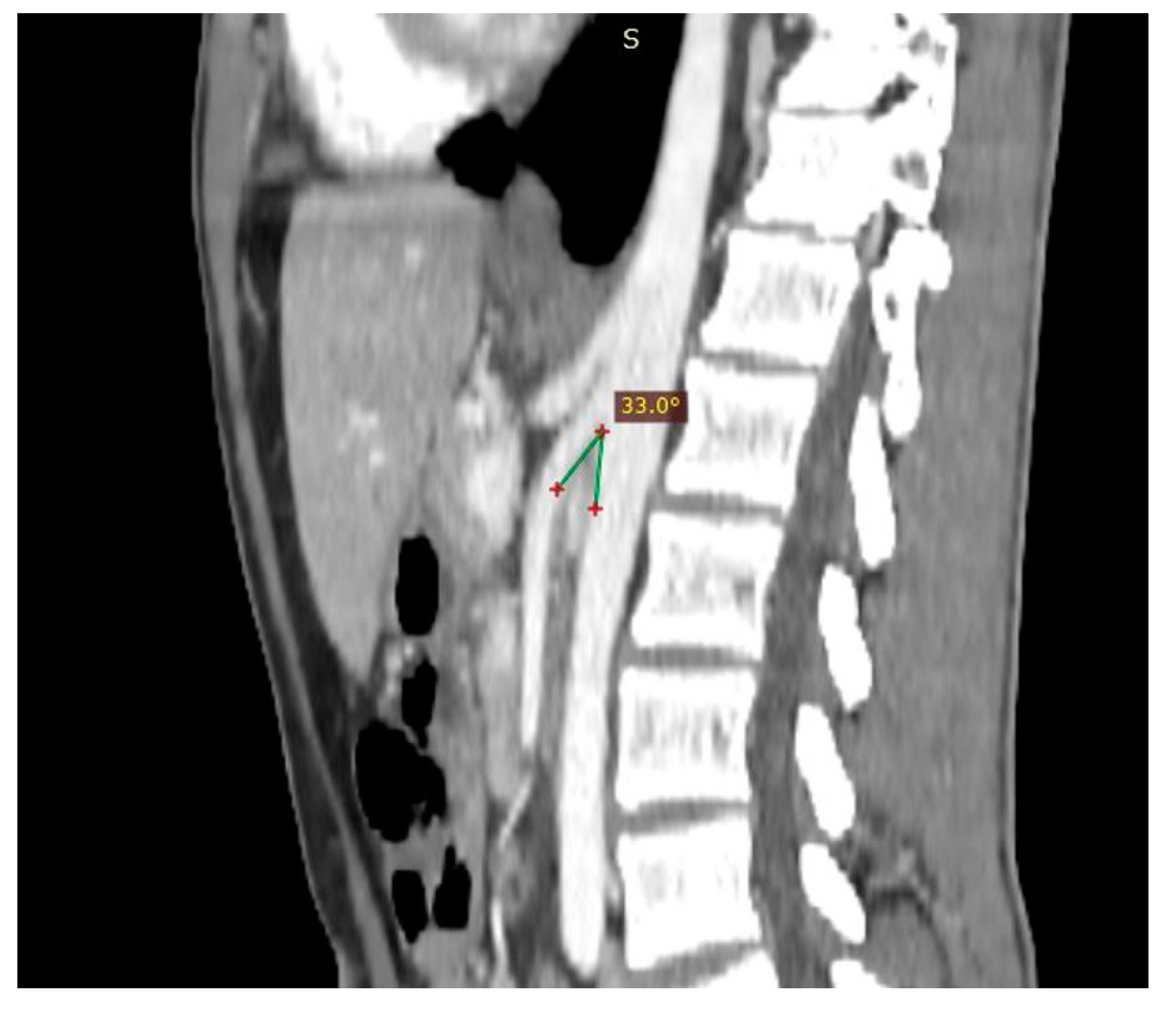

| AMA | CT (post contrast arterial and portal venous phase, sagittal reconstruction), MRI (angiography sequences, sagittal acquisition), US (b-mode, sagittal scans) | <35° | [28] |

| Beck angle | CT (post contrast arterial and portal venous phase, axial scans), MRI (angiography sequences, axial acquisition), US (b-mode, axial scans) | <32° | [3] |

| LRV diameter ratio | >4.9 | [3] | |

| PVR | ECD-US (Doppler sampling in correspondence with the hilar region and stenotic region of the LRV) | >4.7 | [32] |

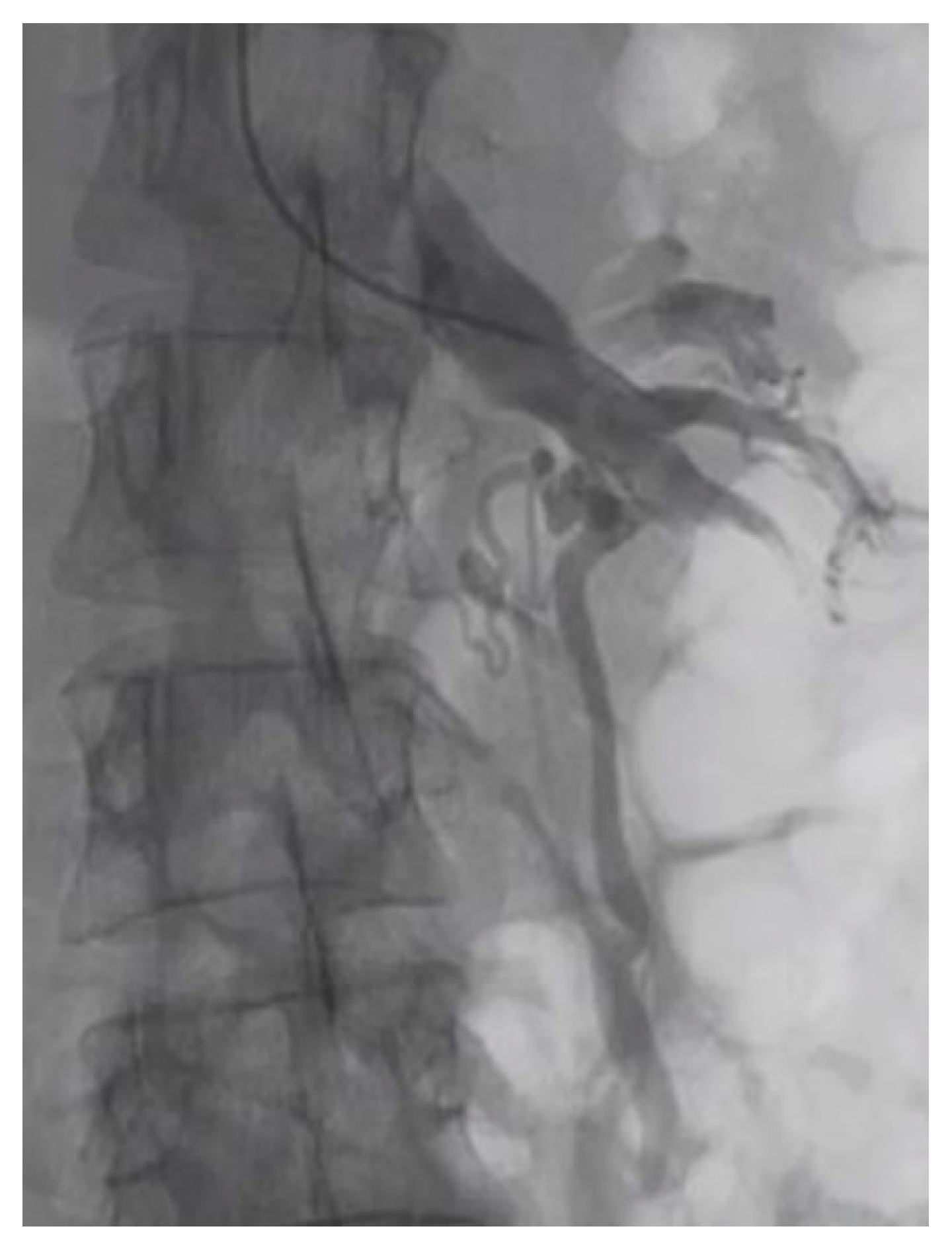

| LRV to IVC pressure gradient | Invasive sampling of venous pressure values in correspondence with the LRV (distal to the stenosis) and in the IVC | >3 mmHg | [22,32,33,34,35,36,37] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Granata, A.; Distefano, G.; Sturiale, A.; Figuera, M.; Foti, P.V.; Palmucci, S.; Basile, A. From Nutcracker Phenomenon to Nutcracker Syndrome: A Pictorial Review. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010101

Granata A, Distefano G, Sturiale A, Figuera M, Foti PV, Palmucci S, Basile A. From Nutcracker Phenomenon to Nutcracker Syndrome: A Pictorial Review. Diagnostics. 2021; 11(1):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010101

Chicago/Turabian StyleGranata, Antonio, Giulio Distefano, Alessio Sturiale, Michele Figuera, Pietro Valerio Foti, Stefano Palmucci, and Antonio Basile. 2021. "From Nutcracker Phenomenon to Nutcracker Syndrome: A Pictorial Review" Diagnostics 11, no. 1: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010101

APA StyleGranata, A., Distefano, G., Sturiale, A., Figuera, M., Foti, P. V., Palmucci, S., & Basile, A. (2021). From Nutcracker Phenomenon to Nutcracker Syndrome: A Pictorial Review. Diagnostics, 11(1), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11010101