Trends in Hospitalization of Patients with Potentially Serious Diseases Evaluated at a Quick Diagnosis Clinic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

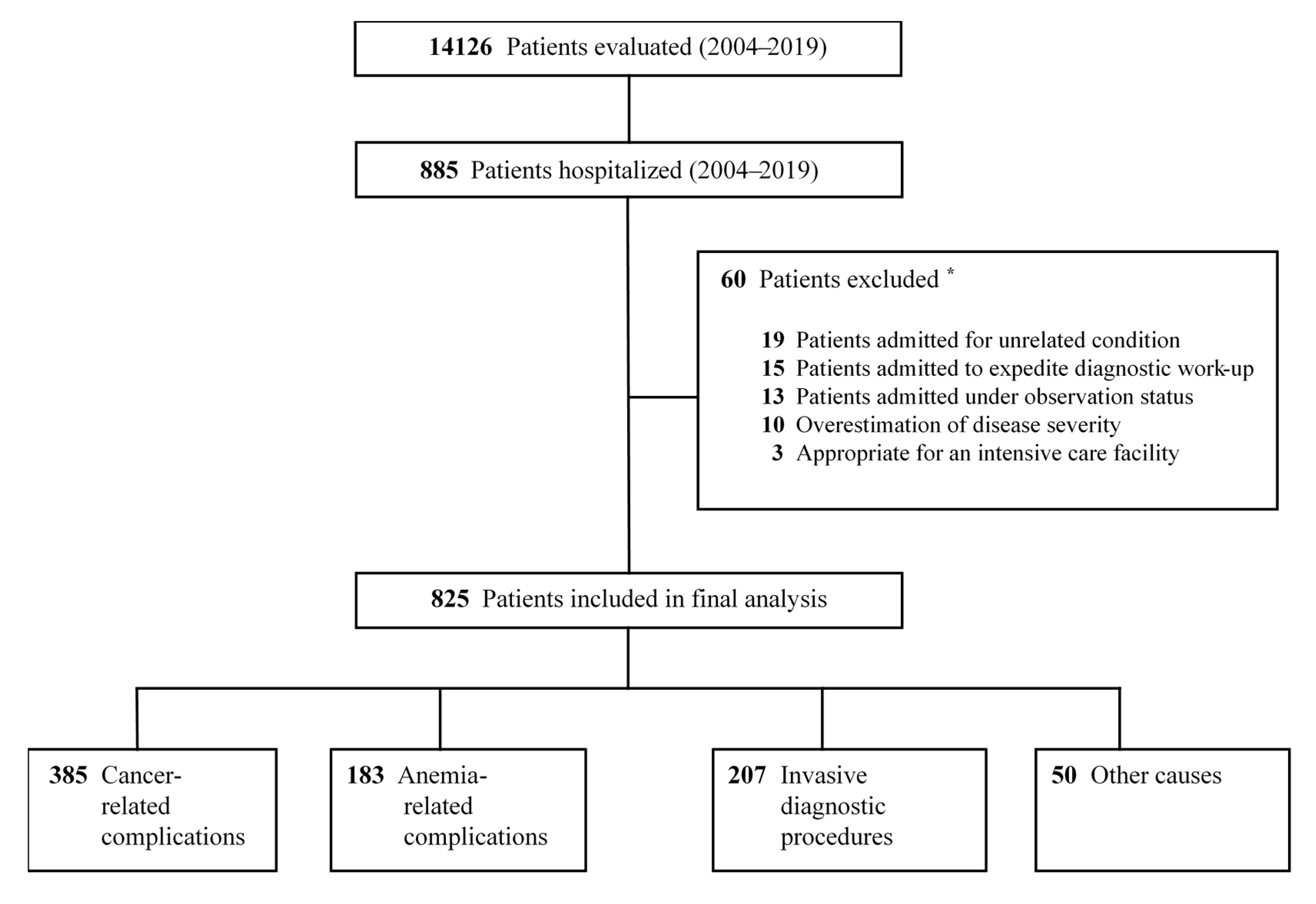

2.2. Study Design and Population

2.3. Study Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Forero, R.; Hillman, K.M.; McCarthy, S.; Fatovich, D.M.; Joseph, A.P.; Richardson, D.B. Access block and ED overcrowding. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2010, 22, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulley, A.G., Jr. The global role of health care delivery science: Learning from variation to build health systems that avoid waste and harm. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28 (Suppl. 3), S646–S653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Martin, A.B.; Hartman, M.; Benson, J.; Catlin, A. National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. National health spending in 2014: Faster growth driven by coverage expansion and prescription drug spending. Health Aff. 2016, 35, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbella, X.; Barreto, V.; Bassetti, S.; Bivol, M.; Castellino, P.; de Kruijf, E.J.; Dentali, F.; Durusu-Tanriöver, M.; Fierbinţeanu-Braticevici, C.; Hanslik, T.; et al. Working Group on Professional Issues and Quality of Care, European Federation of Internal Medicine (EFIM). Hospital ambulatory medicine: A leading strategy for Internal Medicine in Europe. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 54, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pericás, J.M.; Aibar, J.; Soler, N.; López-Soto, A.; Sanclemente-Ansó, C.; Bosch, X. Should alternatives to conventional hospitalisation be promoted in an era of financial constraint? Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 43, 602–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepperd, S.; Doll, H.; Angus, R.M.; Clarke, M.J.; Iliffe, S.; Kalra, L.; Ricauda, N.A.; Tibaldi, V.; Wilson, A.D. Avoiding hospital admission through provision of hospital care at home: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data. CMAJ 2009, 180, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugh, C.W.; Venkatesh, A.K.; Hilton, J.A.; Samuel, P.A.; Schuur, J.D.; Bohan, J.S. Making greater use of dedicated hospital observation units for many short-stay patients could save $3.1 billion a year. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 2314–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aujesky, D.; Roy, P.M.; Verschuren, F.; Righini, M.; Osterwalder, J.; Egloff, M.; Renaud, B.; Verhamme, P.; Stone, R.A.; Legall, C.; et al. Outpatient versus inpatient treatment for patients with acute pulmonary embolism: An international, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2011, 378, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, C.R.; Seidenfeld, J.; Bow, E.J.; Karten, C.; Gleason, C.; Hawley, D.K.; Kuderer, N.M.; Langston, A.A.; Marr, K.A.; Rolston, K.V.; et al. Antimicrobial prophylaxis and outpatient management of fever and neutropenia in adults treated for malignancy: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X.; Aibar, J.; Capell, S.; Coca, A.; López-Soto, A. Quick diagnosis units: A potentially useful alternative to conventional hospitalisation. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 191, 496–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, J.; O’Brien, C.W.; Leff, B.A.; Bolen, S.; Zulman, D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions: A systematic review. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capell, S.; Comas, P.; Piella, T.; Rigau, J.; Pruna, X.; Martínez, F.; Montull, S. Unidad de diagnóstico rápido: Un modelo asistencial eficaz y eficiente. Experiencia de 5 años [Quick and early diagnostic outpatient unit: An effective and efficient assistential model. Five years experience]. Med. Clin. 2004, 123, 247–250. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Rivas, M.; Vidaller, A.; Pujol I Farriols, R.; Mast, R. Unidad de diagnóstico rápido en un hospital de tercer nivel. Estudio descriptivo del primer año y medio de funcionamiento [Rapid diagnosis unit in a third level hospital. Descriptive study of the first year and a half]. Rev. Clin Esp. 2008, 208, 561–563. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X.; Foix, A.; Jordán, A.; Coca, A.; López-Soto, A. Outpatient quick diagnosis units for the evaluation of suspected severe diseases: An observational, descriptive study. Clinics 2011, 66, 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sanclemente-Ansó, C.; Salazar, A.; Bosch, X.; Capdevila, C.; Vallano, A.; Català, I.; Fernandez-Alarza, A.F.; Rosón, B.; Corbella, X. A quick diagnosis unit as an alternative to conventional hospitalization in a tertiary public hospital: A descriptive study. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2013, 123, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X.; Palacios, F.; Inclán-Iríbar, G.; Castañeda, M.; Jordán, A.; Moreno, P.; Coca, A.; López-Soto, A. Quick diagnosis units or conventional hospitalisation for the diagnostic evaluation of severe anaemia: A paradigm shift in public health systems? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2012, 23, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X.; Moreno, P.; Ríos, M.; Jordán, A.; López-Soto, A. Comparison of quick diagnosis units and conventional hospitalization for the diagnosis of cancer in Spain: A descriptive cohort study. Oncology 2012, 83, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X.; Jordán, A.; Coca, A.; López-Soto, A. Quick diagnosis units versus hospitalization for the diagnosis of potentially severe diseases in Spain. J. Hosp. Med. 2012, 7, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X.; Jordán, A.; López-Soto, A. Quick diagnosis units: Avoiding referrals from primary care to the ED and hospitalizations. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 31, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito-Zerón, P.; Nicolás-Ocejo, D.; Jordán, A.; Retamozo, S.; López-Soto, A.; Bosch, X. Diagnosing unexplained fever: Can quick diagnosis units replace inpatient hospitalization? Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 44, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanclemente-Ansó, C.; Salazar, A.; Bosch, X.; Capdevila, C.; Giménez-Requena, A.; Rosón-Hernández, B.; Corbella, X. Perception of quality of care of patients with potentially severe diseases evaluated at a distinct quick diagnostic delivery model: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 434. [Google Scholar]

- Sanclemente-Ansó, C.; Bosch, X.; Salazar, A.; Moreno, R.; Capdevila, C.; Rosón, B.; Corbella, X. Cost-minimization analysis favors outpatient quick diagnosis unit over hospitalization for the diagnosis of potentially serious diseases. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 30, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montori-Palacín, E.; Prieto-González, S.; Carrasco-Miserachs, I.; Altes-Capella, J.; Compta, Y.; López-Soto, A.; Bosch, X. Quick outpatient diagnosis in small district or general tertiary hospitals: A comparative observational study. Medicine 2017, 96, e6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X.; Sanclemente-Ansó, C.; Escoda, O.; Monclús, E.; Franco-Vanegas, J.; Moreno, P.; Guerra-García, M.; Guasch, N.; López-Soto, A. Time to diagnosis and associated costs of an outpatient vs. inpatient setting in the diagnosis of lymphoma: A retrospective study of a large cohort of major lymphoma subtypes in Spain. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, X.; Moreno, P.; Guerra-García, M.; Guasch, N.; López-Soto, A. What is the relevance of an ambulatory quick diagnosis unit or inpatient admission for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer? A retrospective study of 1004 patients. Medicine 2020, 99, e19009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, S.; Suñol, R. An overview of Spanish studies on appropriateness of hospital use. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 1995, 7, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T.; Liberati, A.; Tampieri, A.; Fellin, G.; Gonsalves Mda, L.; Lorenzo, S.; Pearson, M.; Beech, R.; Santos-Eggimann, B. A European version of the Appropriateness Evaluation Protocol. Goals and presentation. The BIOMED I Group on Appropriateness of Hospital Use. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 1999, 15, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangha, O.; Schneeweiss, S.; Wildner, M.; Cook, E.F.; Brennan, T.A.; Witte, J.; Liang, M.H. Metric properties of the appropriateness evaluation protocol and predictors of inappropriate hospital use in Germany: An approach using longitudinal patient data. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2002, 14, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertman, P.M.; Restuccia, J.D. The appropriateness evaluation protocol: A technique for assessing unnecessary days of hospital care. Med. Care 1981, 19, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic. Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oken, M.M.; Creech, R.H.; Tormey, D.C.; Horton, J.; Davis, T.E.; McFadden, E.T.; Carbone, P.P. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1982, 5, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Sukhal, S.; Agarwal, R.; Das, K. Quick diagnosis units--an effective alternative to hospitalization for diagnostic workup: A systematic review. J. Hosp. Med. 2014, 9, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vedsted, P.; Olesen, F. A differentiated approach to referrals from general practice to support early cancer diagnosis—The Danish three-legged strategy. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112 (Suppl. 1), S65–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bislev, L.S.; Bruun, B.J.; Gregersen, S.; Knudsen, S.T. Prevalence of cancer in Danish patients referred to a fast-track diagnostic pathway is substantial. Dan. Med. J. 2015, 62, A5138. [Google Scholar]

- Moseholm, E.; Rydahl-Hansen, S.; Lindhardt, B. Undergoing diagnostic evaluation for possible cancer affects the health-related quality of life in patients presenting with non-specific symptoms. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næser, E.; Møller, H.; Fredberg, U.; Vedsted, P. Mortality of patients examined at a diagnostic centre: A matched cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018, 55, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenman, E.; Palmér, K.; Rydén, S.; Sävblom, C.; Svensson, I.; Rose, C.; Ji, J.; Nilbert, M.; Sundquist, J. Diagnostic spectrum and time intervals in Sweden’s first diagnostic center for patients with nonspecific symptoms of cancer. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, X. Impact of the Availability of a Daycare Center on the Management of Iron-Deficiency Anemia; Department of Internal Medicine, University of Barcelona, Hospital Clínic: Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khati, N.J.; Gorodenker, J.; Hill, M.C. Ultrasound-guided biopsies of the abdomen. Ultrasound Q. 2011, 27, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, I.; Ojo, D.; Dennison, A.R.; Rees, Y.; Elabassy, M.; Garcea, G. Percutaneous pancreatic biopsies-still an effective method for histologic confirmation of malignancy. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2016, 26, 334–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicknell, S.G.; Richenberg, J.; Cooperberg, P.L.; Tiwari, P.; Halperin, L. Early discharge after core liver biopsy: Is it safe and cost-effective? Can. Assoc. Radiol. J. 2002, 53, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pokorny, C.S.; Waterland, M. Short-stay, out-of-hospital, radiologically guided liver biopsy. Med. J. Aust. 2002, 176, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Overall | 2004–2005 | 2005–2006 | 2006–2007 | 2007–2008 | 2008–2009 | 2009–2010 | 2010–2011 | 2011–2012 | 2012–2013 | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | p-Value (Trend) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population, N | 14,126 | 523 | 689 | 720 | 775 | 832 | 849 | 812 | 872 | 949 | 1021 | 1055 | 1140 | 1224 | 1281 | 1384 | |

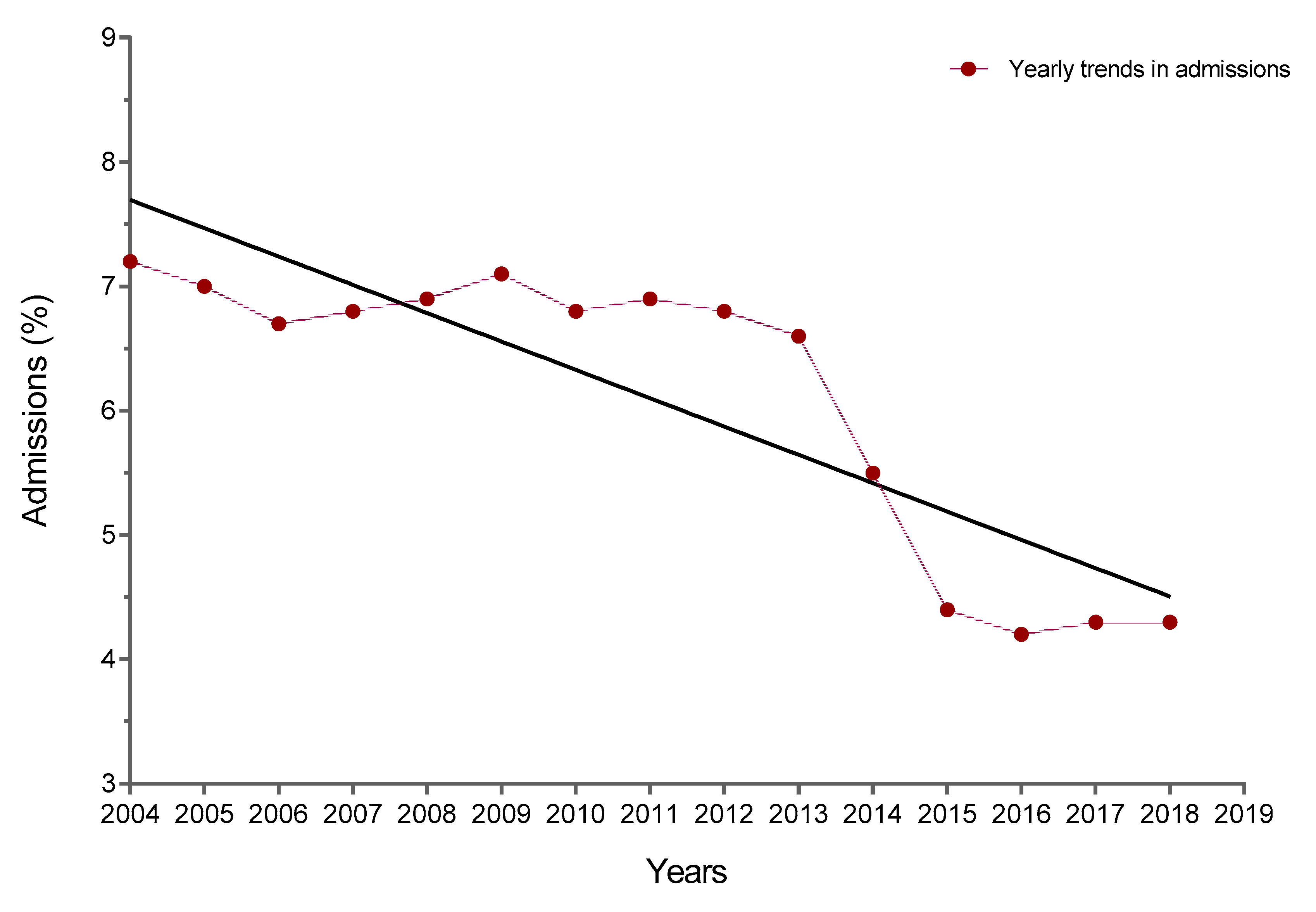

| Admissions, n (%) | 825 (5.8) | 38 (7.2) | 48 (7.0) | 48 (6.7) | 53 (6.8) | 57 (6.9) | 60 (7.1) | 55 (6.8) | 60 (6.9) | 65 (6.8) | 67 (6.6) | 58 (5.5) | 50 (4.4) | 51 (4.2) | 55 (4.3) | 60 (4.3) | <0.0001 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 65.4 (16.1) | 64.6 (12.5) | 65.7 (14.1) | 64.8 (12.9) | 66.0 (14.0) | 62.7 (13.6) | 67.3 (14.9) | 62.9 (15.1) | 68.4 (15.0) | 65.9 (14.4) | 63.6 (15.3) | 67.5 (13.9) | 66.8 (14.2) | 68.1 (13.7) | 64.2 (15.5) | 63.3 (16.0) | 0.1165 |

| Age ≥ 65 years, % | 53.8 | 53.2 | 54.1 | 53.3 | 54.3 | 51.6 | 55.4 | 51.8 | 56.3 | 54.2 | 52.3 | 55.6 | 55.0 | 56.0 | 52.8 | 52.1 | 0.1033 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 406 (49.2) | 17 (44.7) | 23 (47.9) | 25 (52.1) | 26 (49.1) | 30 (52.6) | 27 (45) | 27 (49.1) | 29 (48.3) | 33 (50.8) | 32 (47.8) | 29 (50.0) | 26 (52.0) | 25 (49.1) | 27 (49.1) | 30 (50.0) | 0.0755 |

| Socioeconomic status quartile, n (%) * | 0.1445 | ||||||||||||||||

| Quartile 1 | 116 (14.1) | 5 (13.2) | 7 (14.6) | 7 (14.6) | 8 (15.1) | 9 (15.8) | 9 (15.0) | 7 (12.7) | 8 (13.3) | 9 (13.8) | 9 (13.4) | 7 (12.1) | 6 (12.0) | 6 (11.8) | 9 (16.4) | 10 (16.7) | |

| Quartile 2 | 212 (25.7) | 10 (26.3) | 13 (27.1) | 14 (29.2) | 14 (26.4) | 15 (26.3) | 16 (26.7) | 14 (25.4) | 15 (25.0) | 16 (24.6) | 15 (22.4) | 14 (24.1) | 13 (26.0) | 13 (25.5) | 15 (27.3) | 15 (25.0) | |

| Quartile 3 | 274 (33.2) | 12 (31.6) | 15 (31.3) | 14 (29.2) | 16 (30.2) | 18 (31.6) | 19 (31.7) | 19 (34.5) | 21 (35.0) | 23 (35.4) | 26 (38.8) | 20 (34.5) | 18 (36.0) | 18 (35.3) | 17 (30.9) | 18 (30.0) | |

| Quartile 4 | 223 (27.0) | 11 (28.9) | 13 (27.1) | 13 (27.1) | 15 (28.3) | 15 (26.3) | 16 (26.7) | 15 (27.3) | 16 (26.7) | 17 (26.2) | 17 (25.4) | 17 (29.3) | 13 (26.0) | 14 (27.4) | 14 (25.4) | 17 (28.3) | |

| Charlson index, mean (SD) | 1.88 (1.12) | 1.81 (0.81) | 1.84 (0.92) | 1.90 (1.01) | 1.94 (1.12) | 1.76 (0.87) | 1.98 (1.23) | 1.70 (0.88) | 2.04 (1.19) | 2.20 (1.20) | 1.78 (1.07) | 1.92 (0.95) | 1.88 (1.00) | 1.96 (1.14) | 1.73 (0.99) | 1.84 (0.83) | 0.2867 |

| 0–1, n (%) | 275 (33.3) | 14 (36.8) | 17 (35.4) | 16 (33.3) | 17 (32.1) | 21 (36.8) | 19 (31.7) | 20 (36.4) | 18 (30.0) | 19 (29.2) | 24 (35.8) | 19 (32.8) | 16 (32.0) | 15 (29.4) | 19 (34.5) | 21 (35.0) | |

| 2, n (%) | 365 (44.2) | 15 (39.5) | 19 (39.6) | 20 (41.7) | 22 (41.5) | 25 (43.9) | 27 (45.0) | 25 (45.5) | 27 (45.0) | 29 (44.6) | 29 (43.3) | 26 (44.8) | 24 (48.0) | 25 (49.0) | 26 (47.3) | 26 (43.3) | |

| >3, n (%) | 185 (22.4) | 9 (23.7) | 12 (25.0) | 12 (25.0) | 14 (26.4) | 11 (19.3) | 14 (23.3) | 10 (18.2) | 15 (25.0) | 17 (26.2) | 14 (20.9) | 13 (22.4) | 10 (20.0) | 11 (21.6) | 10 (18.2) | 13 (21.7) | |

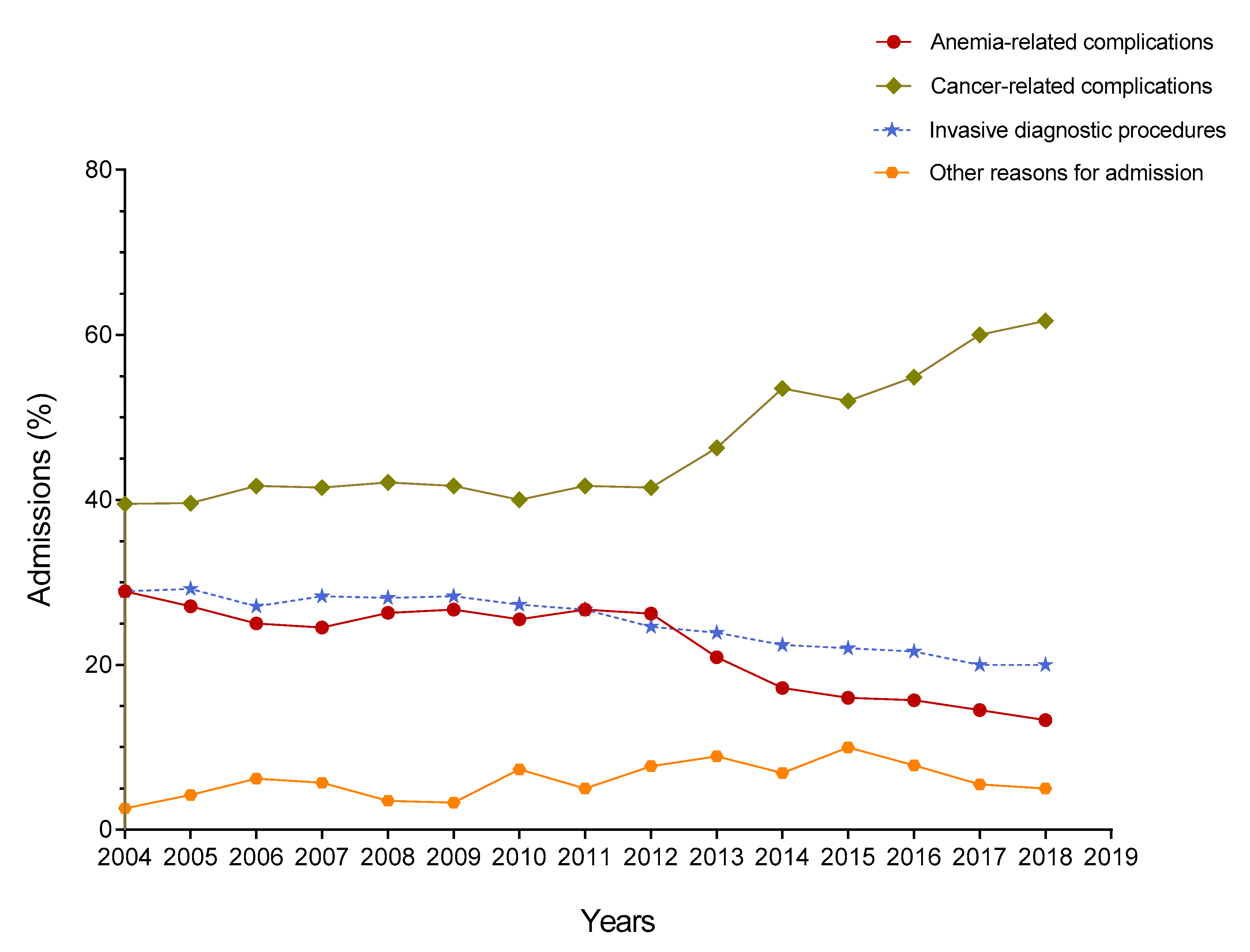

| Cancer patients, n (%) | 433 (52.5) | 17 (44.7) | 22 (45.8) | 23 (47.9) | 26 (49.1) | 27 (47.4) | 29 (48.3) | 25 (45.5) | 29 (48.3) | 30 (46.2) | 35 (52.2) | 34 (58.6) | 28 (56.0) | 31 (60.8) | 37 (67.3) | 40 (66.7) | <0.0001 |

| ECOG-PS score mean (SD) | 2.78 (1.84) | 2.38 (1.36) | 2.60 (1.45) | 2.49 (1.51) | 2.59 (1.52) | 2.49 (1.60) | 2.67 (1.55) | 2.70 (1.49) | 2.79 (1.72) | 2.81 (1.40) | 2.79 (1.67) | 2.87 (1.81) | 2.89 (1.73) | 2.94 (1.86) | 3.01 (1.58) | 3.03 (1.65) | <0.0001 |

| 0–1, n (%) | 77 (17.8) | 5 (29.4) | 5 (22.7) | 6 (26.1) | 6 (23.1) | 7 (25.9) | 6 (20.7) | 5 (20.0) | 5 (17.2) | 5 (16.7) | 6 (17.1) | 5 (14.7) | 4 (14.2) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (10.8) | 4 (10.0) | |

| 2, n (%) | 165 (38.1) | 6 (35.3) | 9 (40.9) | 9 (39.1) | 11 (42.3) | 10 (37.0) | 12 (41.4) | 10 (40.0) | 12 (41.4) | 12 (40.0) | 13 (37.1) | 13 (38.2) | 10 (35.7) | 11 (35.5) | 13 (35.1) | 14 (35.0) | |

| 3–4, n (%) | 191 (44.1) | 6 (35.3) | 8 (36.3) | 8 (34.8) | 9 (34.6) | 10 (37.0) | 11 (37.9) | 10 (40.0) | 12 (41.4) | 13 (43.3) | 16 (45.7) | 16 (47.1) | 14 (50.0) | 16 (51.6) | 20 (54.1) | 22 (55.0) | |

| Time-to-admission, days, median (IQR) | 7.5 (6–9) | 8 (6–9) | 9 (7–10) | 8 (7–10) | 10 (8–11) | 8 (7–9) | 10 (8–12) | 9 (8–10) | 8 (6–9) | 7 (5–8) | 7 (6–8) | 6 (5–7) | 7 (6–8.5) | 5 (4–7) | 6 (5–7) | 5 (4–6) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer-Related Complications |

| Decline in performance status |

| Unmanageable severe pain |

| Other |

| Thromboembolic disease |

| Hypercalcemia |

| Superior vena cava syndrome |

| Brain metastases |

| Spinal cord compression |

| Anemia-Related Complications |

| Cardiovascular complications |

| Unresponsive severe anemia/worsening anemia |

| Recurrent severe anemia |

| Other |

| Invasive Procedures * |

| Computed tomography- or ultrasound-guided biopsy |

| Liver |

| Pancreas |

| Lung/pleura |

| Bone |

| Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| Other |

| Diagnostic and/or therapeutic surgical procedures including laparoscopy and pleuroscopy |

| Arteriography |

| Other Causes |

| Biliary obstruction |

| Active bleeding |

| Malnutrition/starvation |

| Severe electrolyte imbalance |

| Respiratory complications |

| Need for fluid replacement or intravenous medications |

| Infections |

| Infective endocarditis |

| Tuberculosis |

| Spondylodiscitis |

| Visceral leishmaniasis |

| Other |

| Type of Procedure | Overall | 2004–2005 | 2005–2006 | 2006–2007 | 2007–2008 | 2008–2009 | 2009–2010 | 2010–2011 | 2011–2012 | 2012–2013 | 2013–2014 | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | p-Value (Trend) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admissions, n | 825 | 38 | 48 | 48 | 53 | 57 | 60 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 67 | 58 | 50 | 51 | 55 | 60 | |

| Procedure, n (%) | 207 (25.1) | 11 (28.9) | 14 (29.2) | 13 (27.1) | 15 (28.3) | 16 (28.1) | 17 (28.3) | 15 (27.3) | 16 (26.7) | 16 (24.6) | 16 (23.9) | 13 (22.4) | 11 (22) | 11 (21.6) | 11 (20) | 12 (20) | <0.0001 |

| Liver biopsy | 132 (63.8) | 6 (54.5) | 6 (42.9) | 8 (61.5) | 8 (53.3) | 9 (56.3) | 9 (52.9) | 10 (66.7) | 11 (68.8) | 12 (75.0) | 11 (68.8) | 9 (69.2) | 9 (81.8) | 7 (63.6) | 8 (72.7) | 9 (75.0) | 0.0004 |

| Pancreatic biopsy | 17 (8.2) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (20) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Lung/pleural biopsy | 12 (5.8) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Bone biopsy | 5 (2.4) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.0013 |

| ERCP | 33 (15.9) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (13.3) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (12.5) | 4 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (16.7) | 0.0231 |

| Other * | 8 (3.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | 0.1213 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bosch, X.; Ladino, A.; Moreno-Lozano, P.; Jordán, A.; López-Soto, A. Trends in Hospitalization of Patients with Potentially Serious Diseases Evaluated at a Quick Diagnosis Clinic. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10080585

Bosch X, Ladino A, Moreno-Lozano P, Jordán A, López-Soto A. Trends in Hospitalization of Patients with Potentially Serious Diseases Evaluated at a Quick Diagnosis Clinic. Diagnostics. 2020; 10(8):585. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10080585

Chicago/Turabian StyleBosch, Xavier, Andrea Ladino, Pedro Moreno-Lozano, Anna Jordán, and Alfonso López-Soto. 2020. "Trends in Hospitalization of Patients with Potentially Serious Diseases Evaluated at a Quick Diagnosis Clinic" Diagnostics 10, no. 8: 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10080585

APA StyleBosch, X., Ladino, A., Moreno-Lozano, P., Jordán, A., & López-Soto, A. (2020). Trends in Hospitalization of Patients with Potentially Serious Diseases Evaluated at a Quick Diagnosis Clinic. Diagnostics, 10(8), 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics10080585