Genomic Landscape of Poorly Differentiated Gastric Carcinoma: An AACR GENIE® Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographic of PGC

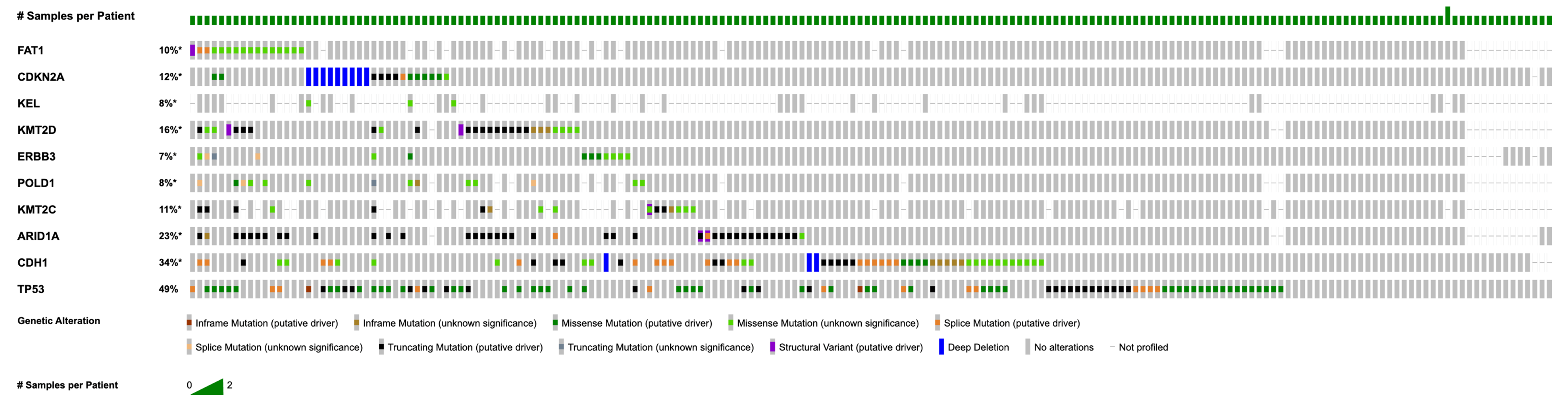

3.2. Recurrent Mutations and Copy Number Alterations

3.3. Analysis by Race and Sex

3.4. Pairwise Analysis of Mutations

3.5. Primary and Metastatic Tumors

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Overview and Genomic Landscape

4.2. Race- and Sex-Stratified Mutational Patterns

4.3. Core Mutational Findings and Pathway Involvement

4.4. Co-Occurrence and Mutual Exclusivity Patterns

4.5. Primary Versus Metastatic Differences and Clinical Correlates

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PGC | poorly differentiated carcinoma of the stomach |

| AACR | American Association for Cancer Research |

| miRNA | micro-RNA |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| TP53 | tumor protein p53 |

| CDH1 | cadherin 1 |

| ARID1A | AT-rich interactive domain 1A |

| KMT2C | lysine (K)-specific methyltransferase 2C |

| POLD1 | DNA polymerase delta1, catalytic subunit |

| ERBB3 | Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3 |

| KMT2D | lysine methyltransferase 2D |

| KEL | Kell metallo-endopeptidase |

| CDK2NA | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A |

| FAT1 | FAT atypical cadherin 1 |

| CCNE1 | cyclin E1 |

| FGFR2 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 |

| MET | MET proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase |

| MYC | MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor |

| KRAS | Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| ERBB2 | Erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 |

| CDKN2B | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2B |

| PTEN | phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| MLH1 | MutL homolog 1 |

| ATM | ATM serine/threonine kinase |

| BRCA2 | BRCA2, DNA repair-associated |

| TNM | tumor node metastasis |

| LOH | loss of heterozygosity |

| CpG | cytosine, guanine |

| APC | adenomatous polyposis coli |

| DCC | deleted in colorectal cancer |

| GATK | genome analysis toolkit |

| ANNOVAR | ANNOtate VARiation |

| PIK3CA | phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha |

| CNAs | copy number alterations |

| TMB | tumor mutational burden |

| VAF | variant allele frequency |

| VUS | variants of uncertain significance |

| MAF | mutation annotation format |

| FDR | false discovery rate |

| ZFHX4 | zinc finger homeobox 4 |

| AGO2 | argonaute 2, RISC catalytic component |

| AFDN | afadin, adherens junction formation factor |

| AFF3 | AF4/FMR2 family, member 3 |

| BCL9 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 9 |

| CDX2 | caudal type homeobox 2 |

| CLTCL1 | clathrin, heavy chain-like 1 |

| CREB3L1 | cAMP-responsive element binding protein 3-like 1 |

| CREB3L2 | cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein 3-like 2 |

| DNA2 | DNA replication helicase/nuclease 2 |

| KCNJ5 | potassium inwardly rectifying channel subfamily J member 5 |

| LIG1 | DNA ligase 1 |

| MLF1 | myeloid leukemia factor 1 |

| ZNF384 | zinc finger protein 384 |

| NDRG1 | N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 |

| PBX1 | pre-B-cell leukemia transcription factor 1 |

| PCM1 | pericentriolar material 1 |

| PER1 | period circadian regulator 1 |

| PTEN | phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 |

| MYC | MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| NDRG1 | N-myc downstream regulated 1 |

| STIL | SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus |

| THRAP3 | thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein 3 |

| CUP | cancer of unknown primary |

References

- Hamilton, S.R.; Aaltonen, L.A. (Eds.) World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cancer Research, UK. Types and Grades of Stomach Cancer. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/stomach-cancer/types-and-grades (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Nagtegaal, I.D.; Odze, R.D.; Klimstra, D.; Paradis, V.; Rugge, M.; Schir-macher, P.; Washington, K.M.; Carneiro, F.; Cree, I.A. The WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 2020, 76, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Liu, J.; Wang, F.; Zheng, G.; Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Xu, G.; Guo, M.; Lian, X.; Zhang, H. Prognostic value of differentiation status in gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adachi, Y.; Yasuda, K.; Inomata, M.; Sato, K.; Shiraishi, N.; Kitano, S. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma: Well versus poorly differentiated type. Cancer 2000, 89, 1418–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fock, K.M. Review article: The epidemiology and prevention of gastric cancer. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 40, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahara, E. Genetic pathways of two types of gastric cancer. IARC Sci. Publ. 2004, 157, 327–349. [Google Scholar]

- Tahara, E. Molecular biology of gastric cancer. World J. Surg. 1995, 19, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Qu, Y.P.; Hou, P. Pathogenetic mechanisms in gastric cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 13804–13819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Stomach Cancer: Stages. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/stomach-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/staging.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Correa, P.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Camargo, M.C. The future of gastric cancer prevention. Gastric Cancer 2004, 7, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, V.; Labianca, R.; Beretta, G.D.; Gatta, G.; de Braud, F.; Van Cutsem, E. Gastric cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2009, 71, 127–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehara, Y.; Anai, H.; Kusumoto, H.; Sugimachi, K. Poorly differentiated human gastric carcinoma is more sensitive to antitumor drugs than well differentiated carcinoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 1987, 13, 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, R.E.; Al Hallak, M.N.; Diab, M.; Azmi, A.S. Gastric cancer: A comprehensive review of current and future treatment strategies. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2020, 39, 1179–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Institute for Cancer Research. Targeted Therapies: Precision Weapons in the War on Cancer. Available online: https://www.aicr.org/resources/blog/targeted-therapies-precision-weapons-in-the-war-on-cancer (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- MedlinePlus. TP53 Gene. Available online: https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/tp53 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Kim, M.; Seo, A.N. Molecular pathology of gastric cancer. J. Gastric Cancer 2022, 22, 273–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, E.; Yoshihara, K.; Kim, H.; Mills, G.M.; Treviño, V.; Verhaak, R.G.W. Comparison of gene expression patterns across 12 tumor types identifies a cancer supercluster characterized by TP53 mutations and cell cycle defects. Oncogene 2015, 34, 2732–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voutsadakis, I.A. Gastric adenocarcinomas with CDX2 induction show higher frequency of TP53 and KMT2B mutations and MYC amplifications but similar survival compared with cancers with no CDX2 induction. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muquith, M.; Hsiehchen, D. Landscape and saturation analysis of mutations associated with race in cancer genomes by clinical sequencing. Oncologist 2024, 29, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACR Project GENIE Consortium. AACR Project GENIE: Powering precision medicine through an international consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spratt, D.E.; Chan, T.; Waldron, L.; Speers, C.; Feng, F.Y.; Ogunwobi, O.O.; Osborne, J.R. Racial/ethnic disparities in genomic sequencing. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1070–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totoki, Y.; Saito-Adachi, M.; Shiraishi, Y.; Komura, D.; Nakamura, H.; Suzuki, A.; Tatsuno, K.; Rokutan, H.; Hama, N.; Yamamoto, S.; et al. Multiancestry genomic and transcriptomic analysis of gastric cancer. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, E.; Bahadirli-Talbott, A.; Shih, I.M. Frequent CCNE1 amplification in endometrial intraepithelial carcinoma and uterine serous carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27, 1014–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conca, E.; Lorenzini, D.; Minna, E.; Agnelli, L.; Duca, M.; Gentili, M.; Bodini, B.; Polignano, M.; Mantiero, M.; Damian, S.; et al. Genomic instability and CCNE1 amplification as emerging biomarkers for stratifying high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1633410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.; Maj, C.; Gehlen, J.; Borisov, O.; Haas, S.L.; Gockel, I.; Vieth, M.; Piessen, G.; Alakus, H.; Vashist, Y.; et al. Dissecting the genetic heterogeneity of gastric cancer. eBioMedicine 2023, 92, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.J.; Kim, K.M.; Choi, J.R.; Choi, S.W.; Rhyu, M.G. Relationship between intratumor histological heterogeneity and genetic abnormalities in gastric carcinoma with microsatellite instability. Int. J. Cancer. 1999, 82, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, N.; Wang, C.X.; Lager, A.; Maron, S.; Shroff, S.; Arndt, N.; Peterson, B.; Kupfer, S.S.; Ma, C.; Misdraji, J.; et al. Morphologic and molecular analysis of early-onset gastric cancer. Cancer 2021, 127, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Pelaez, J.; Barbosa-Matos, R.; Gullo, I.; Carneiro, F.; Oliveira, C. Histological and mutational profile of diffuse gastric cancer: Current knowledge and future challenges. Mol. Oncol. 2021, 15, 2841–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelico, G.; Attanasio, G.; Colarossi, L.; Colarossi, C.; Montalbano, M.; Aiello, E.; Di Vendra, F.; Mare, M.; Orsi, N.; Memeo, L. ARID1A mutations in gastric cancer: A review with focus on clinicopathological features, molecular background and diagnostic interpretation. Cancers 2024, 16, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xiu, J.; Baca, Y.; Battaglin, F.; Arai, H.; Kawanishi, N.; Soni, S.; Zhang, W.; Millstein, J.; Salhia, B.; et al. Large-scale analysis of KMT2 mutations defines a distinctive molecular subset with treatment implication in gastric cancer. Oncogene 2021, 40, 4894–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrin, L.; Fanale, D.; Brando, C.; Fiorino, A.; Corsini, L.R.; Sciacchitano, R.; Filorizzo, C.; Dimino, A.; Russo, A.; Bazan, V. POLE, POLD1, and NTHL1: The last but not the least hereditary cancer-predisposing genes. Oncogene 2021, 40, 5893–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Iwamatsu, A.; Shinohara-Kanda, A.; Ihara, S.; Fukui, Y. Activation of ErbB3–PI3-kinase pathway is correlated with malignant phenotypes of adenocarcinomas. Oncogene 2003, 22, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Shin, H.C.; Heo, Y.J.; Ha, S.Y.; Jang, K.-T.; Kim, S.T.; Kang, W.K.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.-M. CCNE1 amplification is associated with liver metastasis in gastric carcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astolfi, A.; Pantaleo, M.A.; Indio, V.; Urbini, M.; Nannini, M. The emerging role of the FGF/FGFR pathway in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, M.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y. Targeting p53 pathways: Mechanisms, structures and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Varshney, A.; Kumar, P.; Kaur, M.; Kumar, V.; Shekhar, R.; Devi, R.; Priyanka, P.; Khan, M.; Saxena, S. MicroRNA-874–mediated inhibition of the major G1/S phase cyclin, CCNE1, is lost in osteosarcomas. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 21264–21281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yan, B.; Zhao, J.; Yang, A.; Zhang, R. MicroRNA-7 arrests cell cycle in G1 phase by targeting CCNE1 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 443, 1078–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spirina, L.V.; Avgustinovich, A.V.; Bakina, O.V.; Afanas’ev, S.G.; Volkov, M.Y.; Vtorushin, S.V.; Kovaleva, I.V.; Klyushina, T.S.; Munkuev, I.O. Targeted sequencing in gastric cancer: Association with molecular characteristics and FLOT therapy effectiveness. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.J.; Lee, C.S. The role of the AT-rich interaction domain 1A (ARID1A) gene in human carcinogenesis. Genes 2024, 15, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.V.N.P.; Schnack, T.H.; Poulsen, T.S.; Christiansen, A.P.; Høgdall, C.K.; Høgdall, E.V. Genomic sub-classification of ovarian clear cell carcinoma revealed by distinct mutational signatures. Cancers 2021, 13, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, S.; Kulakova, K.; Hanratty, K.; Khan, R.; Casserly, P.; Crown, J.; Walsh, N.; Kennedy, S. Molecular analysis of salivary and lacrimal adenoid cystic carcinoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yan, H.B.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.-Y.; Jiang, Y.-H.; Peng, G.; Wu, F.-Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.-Y.; Liu, F. Enhancement of E-cadherin expression and processing and driving of cancer metastasis by ARID1A deficiency. Oncogene 2021, 40, 5468–5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Pol, S.; Ma, L.; Joshi, R.P.; Arber, D.A. A survey of somatic mutations in 41 genes in a cohort of T-cell lymphomas identifies frequent mutations in genes involved in epigenetic modification. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2019, 27, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.A.; Jaeger, E.; Hagemann, I.S.; Behdad, A.; Layng, K.V.; Gerratana, L.; Mauer, E.; Shah, A.N.; D’aMico, P.; Flaum, L.; et al. Molecular characterization of patients with metastatic invasive lobular carcinoma: Using real-world data to describe this unique clinical entity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 4485–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porkka, N.; Lahtinen, L.; Ahtiainen, M.; Böhm, J.P.; Kuopio, T.; Eldfors, S.; Mecklin, J.; Seppälä, T.T.; Peltomäki, P. Epidemiological, clinical, and molecular characterization of Lynch-like syndrome. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Miyazaki, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Makino, T.; Yamasaki, M.; Nakajima, K.; Ikeda, J.-I.; Mori, M.; et al. Predictive value of MLH1 and PD-L1 expression for prognosis and response to preoperative chemotherapy in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2019, 22, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes Bayne, H.E.; Suleiman, R.; Eiring, R.A.; McGarrah, P.; Thome, S.; Graham, R.; Garcia, J.; Halfdanarson, T. CDX2 expression as a predictive and prognostic biomarker of 5-FU response in cancer of unknown primary. ESMO Open 2025, 10, 105515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 102 (54.26%) |

| Male | 82 (43.62%) | |

| Age category | Adult | 187 (99.47%) |

| Pediatric | 1 (0.53%) | |

| Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic | 136 (72.34%) |

| Hispanic | 34 (18.08%) | |

| Unknown/Not Collected | 18 (9.57%) | |

| Race | White | 115 (61.17%) |

| Black | 21 (11.17%) | |

| Asian | 19 (10.11%) | |

| Other | 18 (9.57%) | |

| Unknown | 11 (5.85%) | |

| Sample Type 1 | Primary | 135 (71.43%) |

| Metastasis | 48 (25.40%) | |

| Not Collected/Unspecified | 6 (3.17%) |

| Gene (Chi-Squared) | White (n, %) | Non-White (n, %) | p-Value | q-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFDN | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| AFF3 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| BCL9 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| CDX2 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| CLTCL1 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| CLYBL | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| CREB3L1 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| CREB3L2 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| CRTC3 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| DNA2 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| FNBP1 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| KCNJ5 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| KDSR | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| LIG1 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| MLF1 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| NDRG1 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| NIN | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| PBX1 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| PCM1 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| PDE4DIP | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| PER1 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| STIL | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| THRAP3 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| ZNF384 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.00%) | <1 × 10−10 | <1 × 10−10 |

| Gene (Chi-Squared) | Male (n, %) | Female (n, %) | p-value | q-value |

| CCNE1 | 1 (1.05%) | 12 (15.79%) | 2.883 × 10−4 | 0.205 |

| ZFHX4 | 2 (33.33%) | 0 (0.00%) | 3.918 × 10−3 | 1.00 |

| AGO2 | 1 (1.72%) | 6 (13.64%) | 0.0405 | 1.00 |

| ERBB3 | 4 (4.04%) | 10 (12.66%) | 0.0482 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lodenquai, J.; Morris, T.J.; Garcia, A.; Sokolovski, E.; Saglimbeni, G.S.; Hsia, B.; Tauseef, A. Genomic Landscape of Poorly Differentiated Gastric Carcinoma: An AACR GENIE® Project. Life 2026, 16, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16020209

Lodenquai J, Morris TJ, Garcia A, Sokolovski E, Saglimbeni GS, Hsia B, Tauseef A. Genomic Landscape of Poorly Differentiated Gastric Carcinoma: An AACR GENIE® Project. Life. 2026; 16(2):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16020209

Chicago/Turabian StyleLodenquai, Joshua, Tyson J. Morris, Ava Garcia, Emely Sokolovski, Grace S. Saglimbeni, Beau Hsia, and Abubakar Tauseef. 2026. "Genomic Landscape of Poorly Differentiated Gastric Carcinoma: An AACR GENIE® Project" Life 16, no. 2: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16020209

APA StyleLodenquai, J., Morris, T. J., Garcia, A., Sokolovski, E., Saglimbeni, G. S., Hsia, B., & Tauseef, A. (2026). Genomic Landscape of Poorly Differentiated Gastric Carcinoma: An AACR GENIE® Project. Life, 16(2), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16020209