General Movements Assessment and Amiel-Tison Neurologic Examination in Neonates and Infants: Correlations and Prognostic Values Regarding Neuromotor Outcomes

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- To identify the correlations between the normal and abnormal results of the GMA and Amiel-Tison neurologic examinations performed in a population of NICU graduates at 40 weeks corrected age (Term Equivalent Age—TEA) and 12 weeks corrected age.

- -

- To identify the prognostic value of the two examinations and the different items used for detecting the risk of cerebral palsy or the risk of gross motor delay (independent sitting and independent walking).

- -

- To verify by, using logistic regression models, if the combination of results from the two examinations at term-equivalent age and 12 weeks corrected age results in a better prognostic value than using the result of each examination separately.

2. Materials and Methods

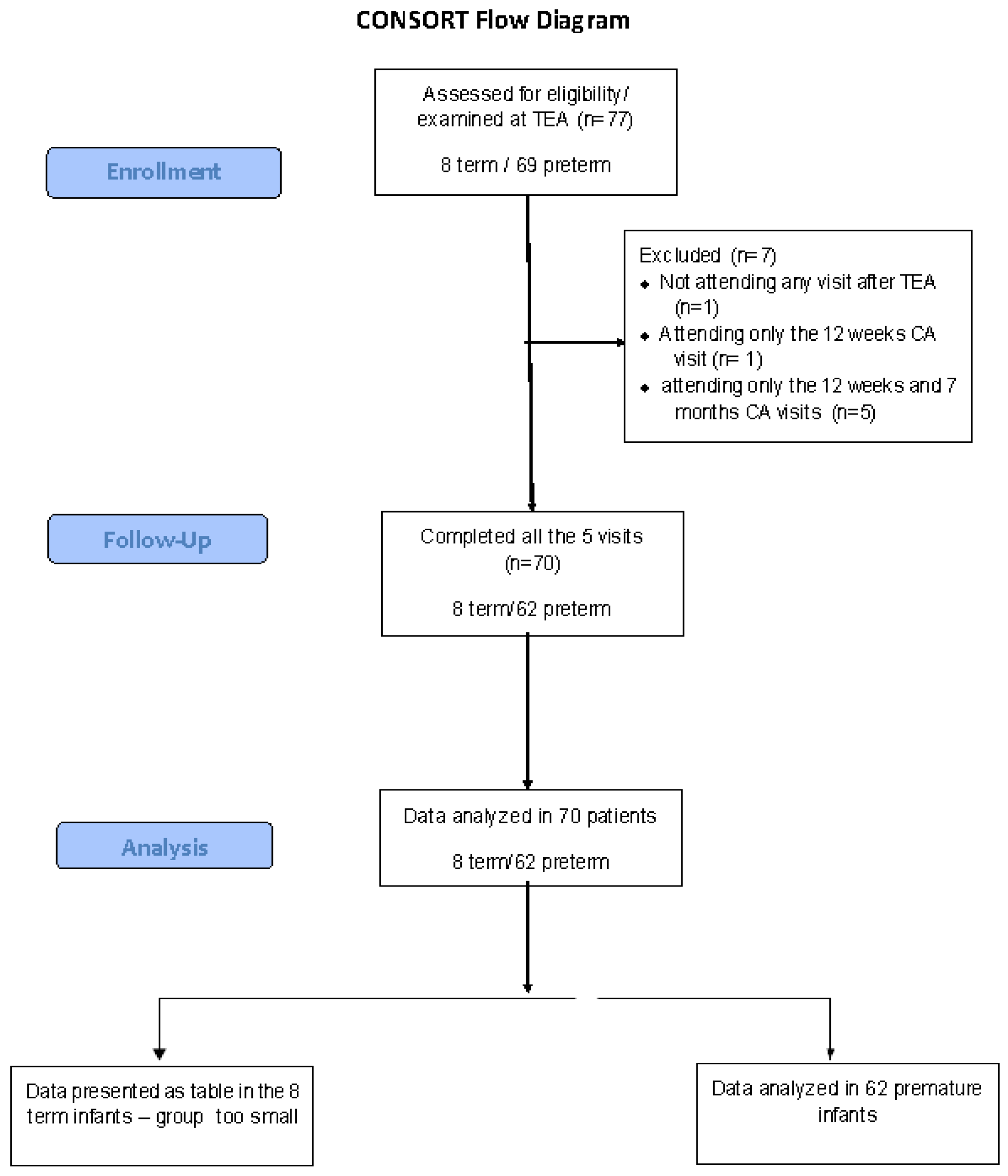

2.1. Population Studied

- -

- -

- The informed consent of the family has been obtained.

- -

- The patient was followed until 24 months corrected age or until a diagnosis of cerebral palsy (CP) was established—whichever occurred sooner.

2.2. Neurologic Examinations

- -

- -

- -

2.3. Outcome Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

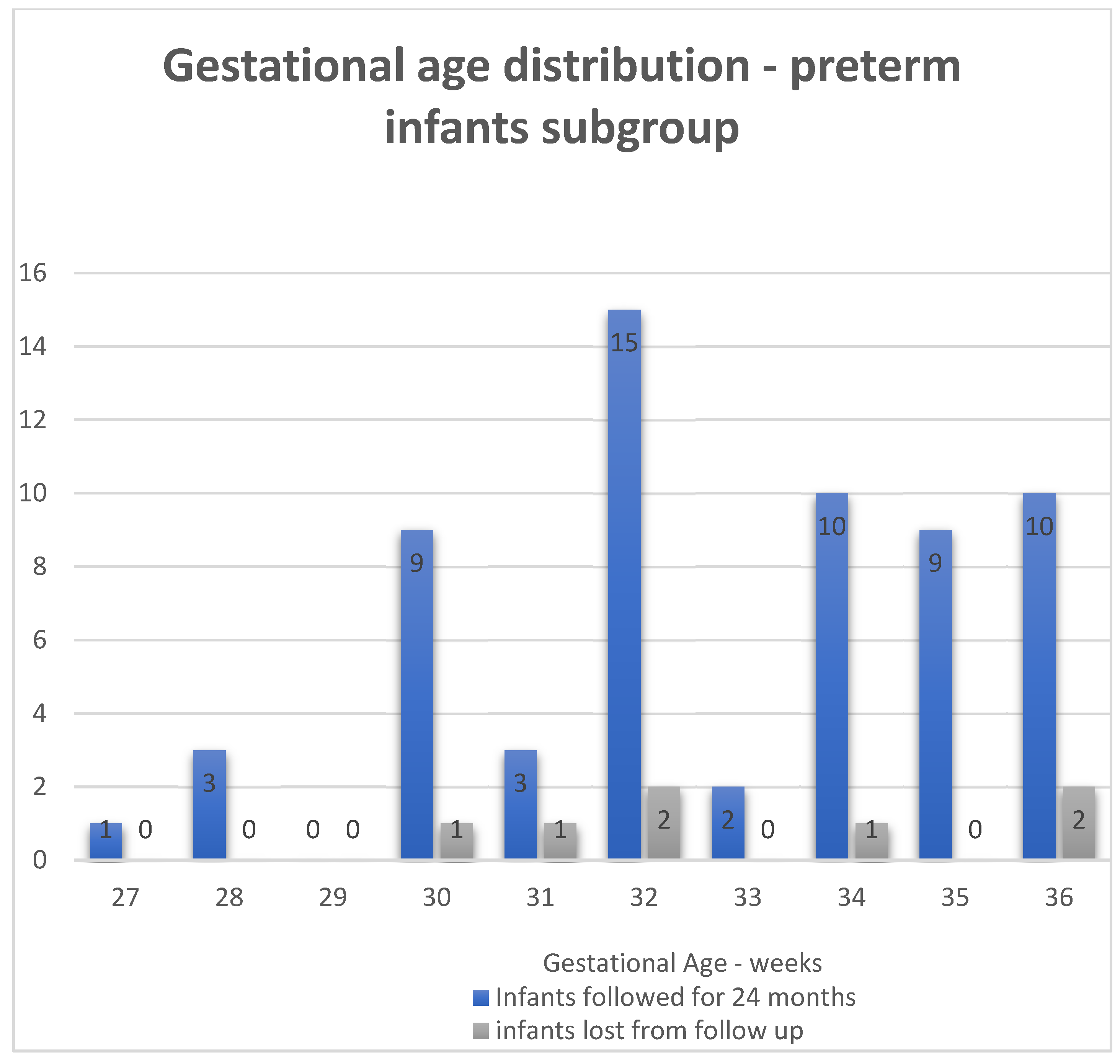

3.1. General Characteristics of the Population

3.2. GMA Examination at TEA and 12 Weeks Corrected Age—Analysis of the Whole Group

3.3. Amiel-Tison Neurologic Evaluation at TEA and 12 Weeks CA—Whole Group

3.4. Correlation Between GMA and Amiel-Tison Examinations—Whole Group

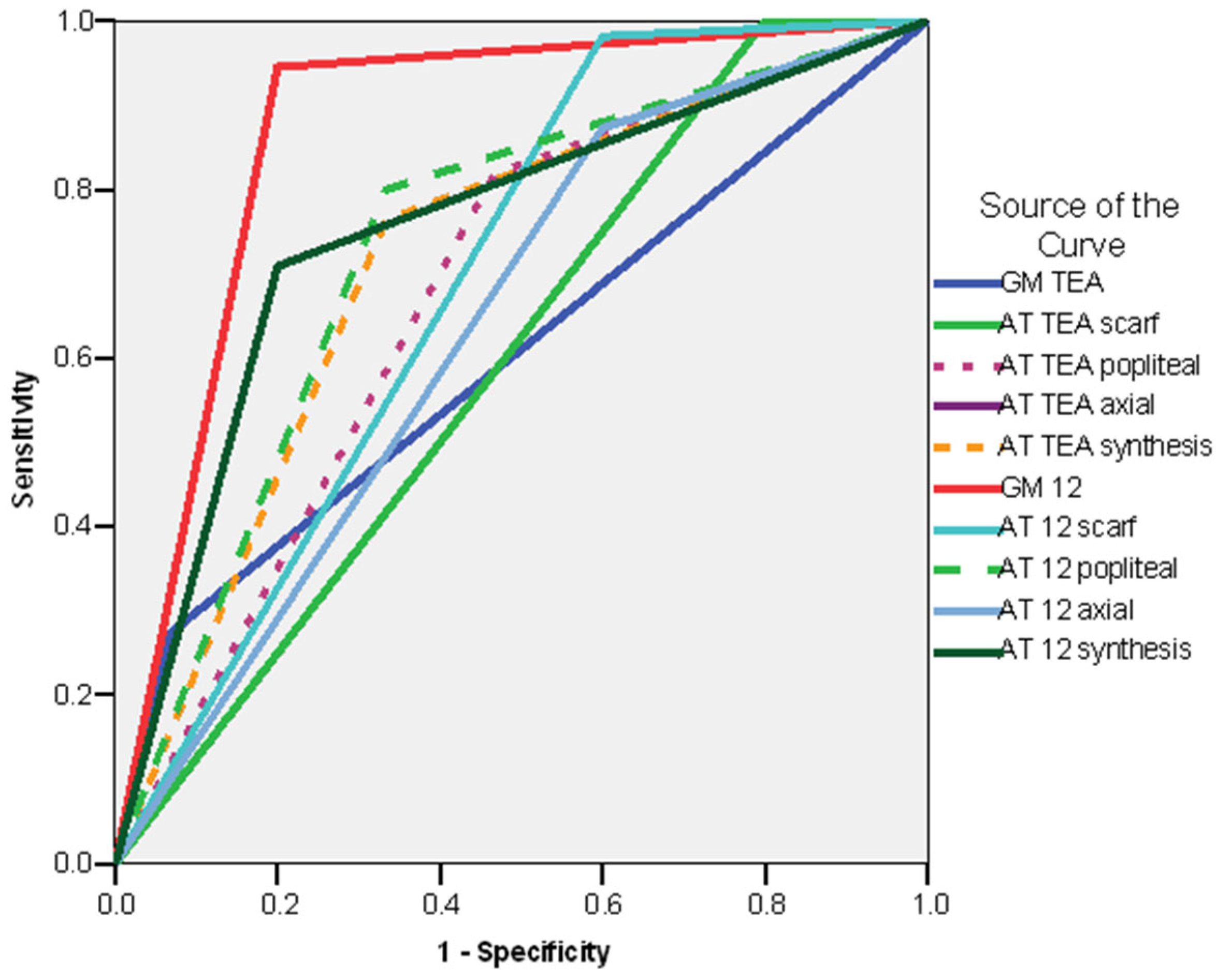

3.5. Logistic Regression Models

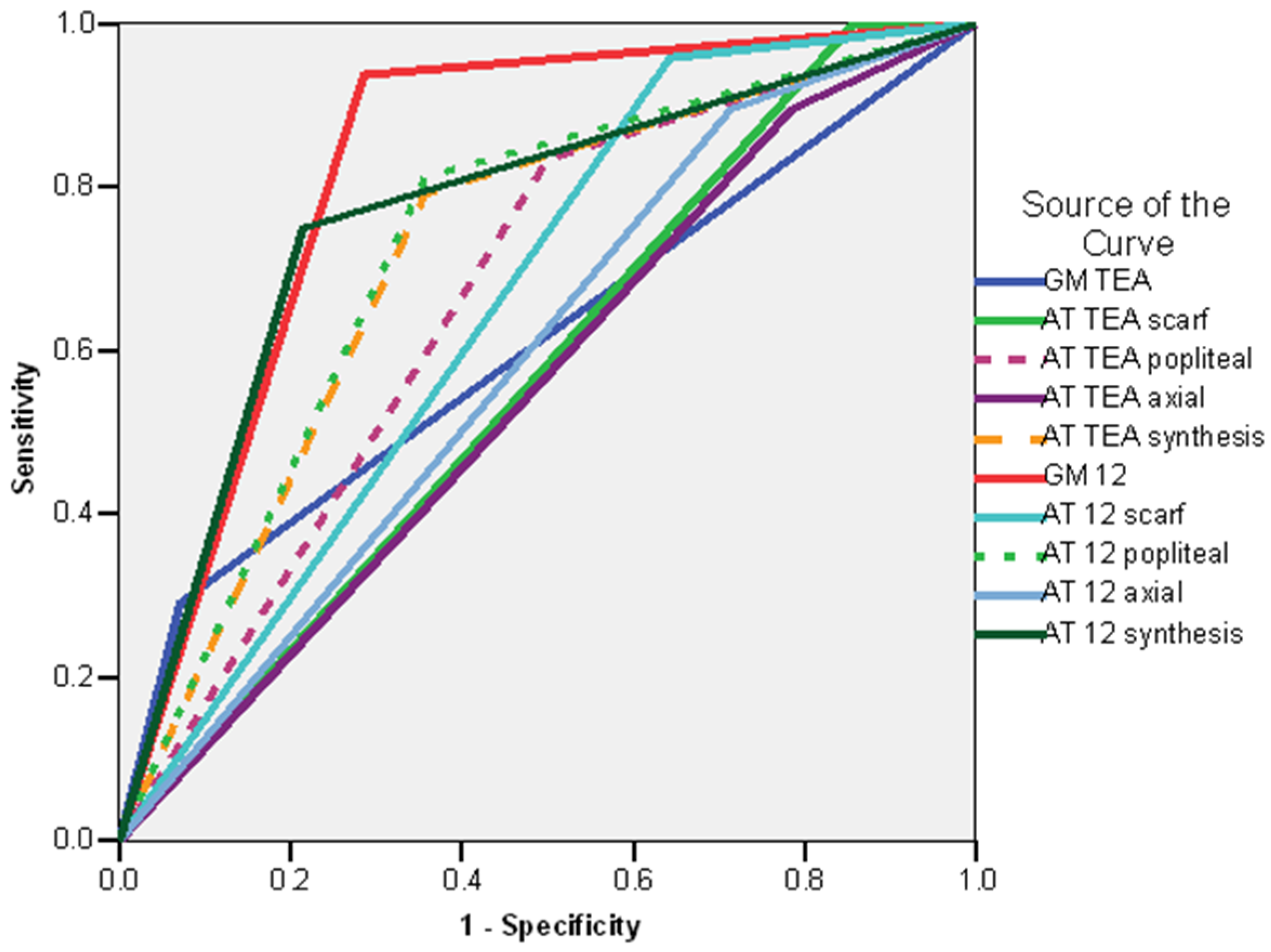

3.5.1. Logistic Regression Models—Whole Group

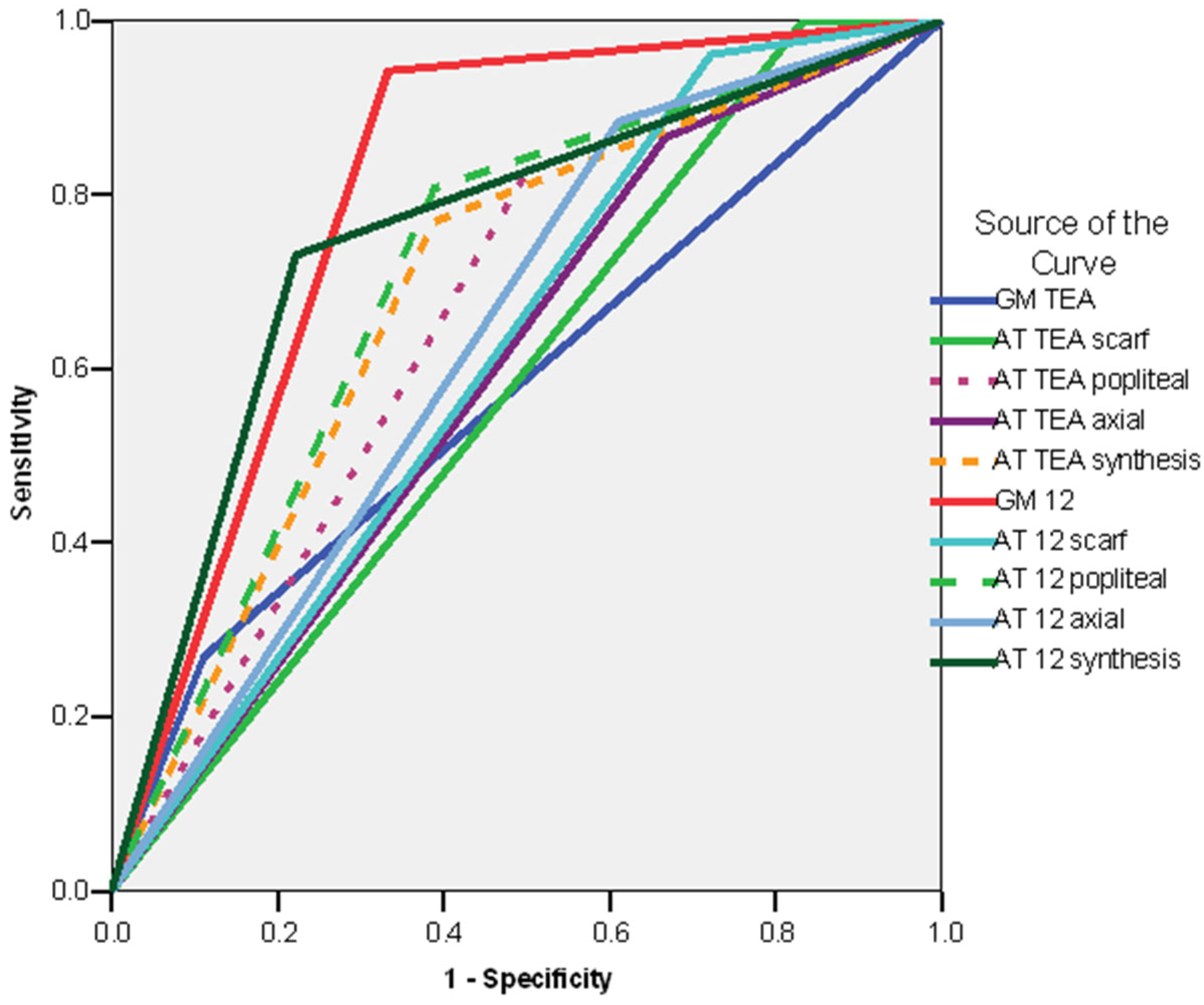

3.5.2. Logistic Regression Models—Subgroup of Preterm Infants

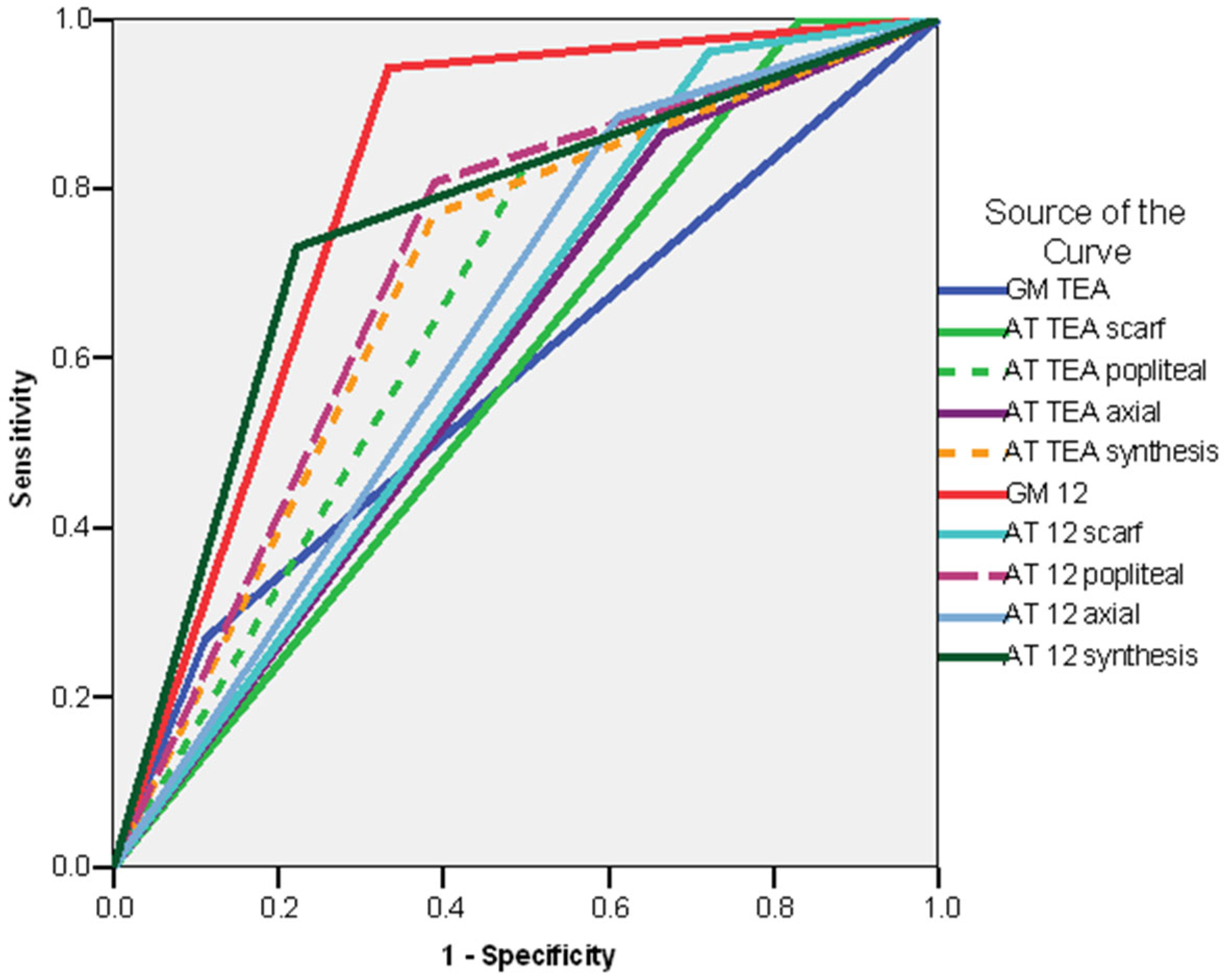

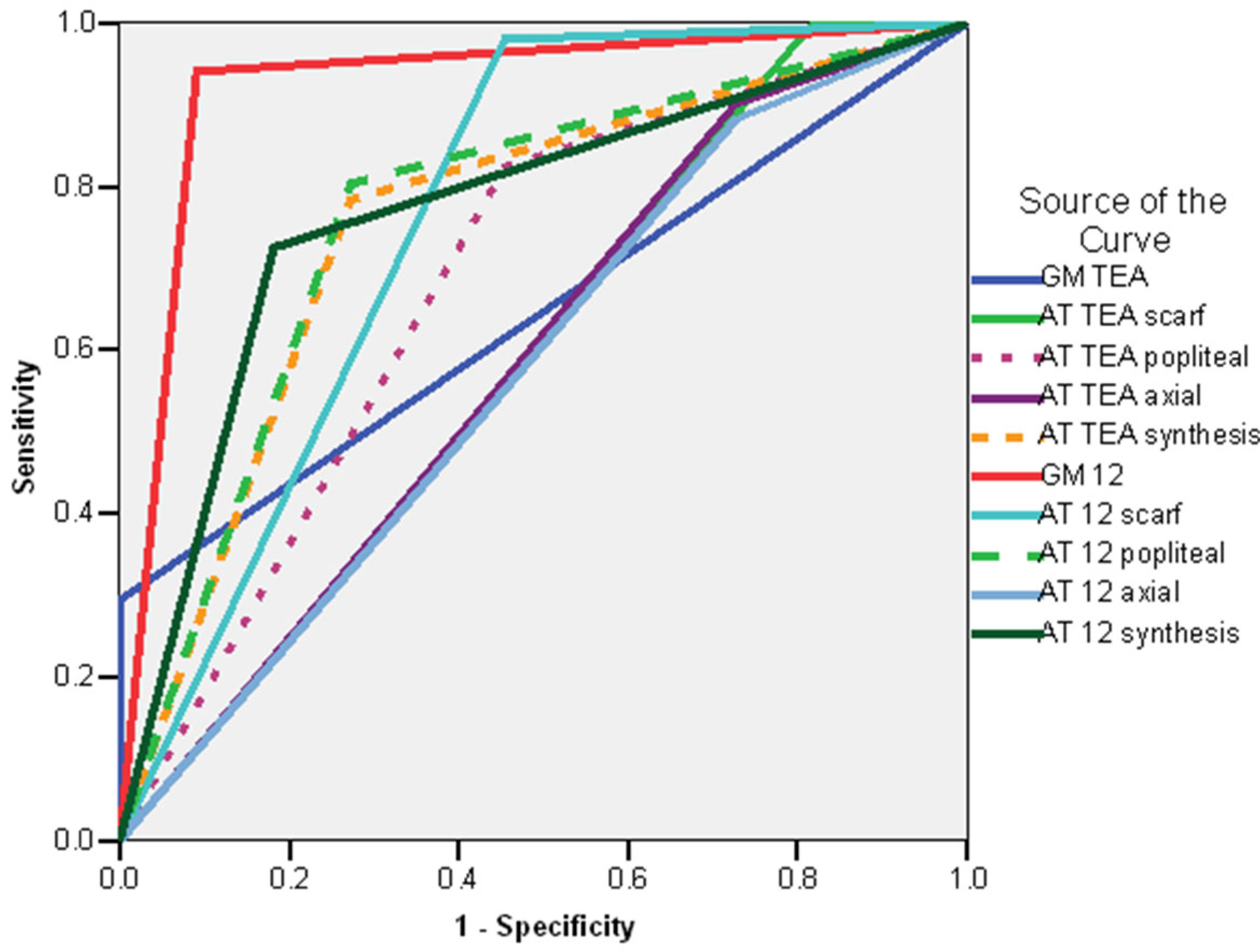

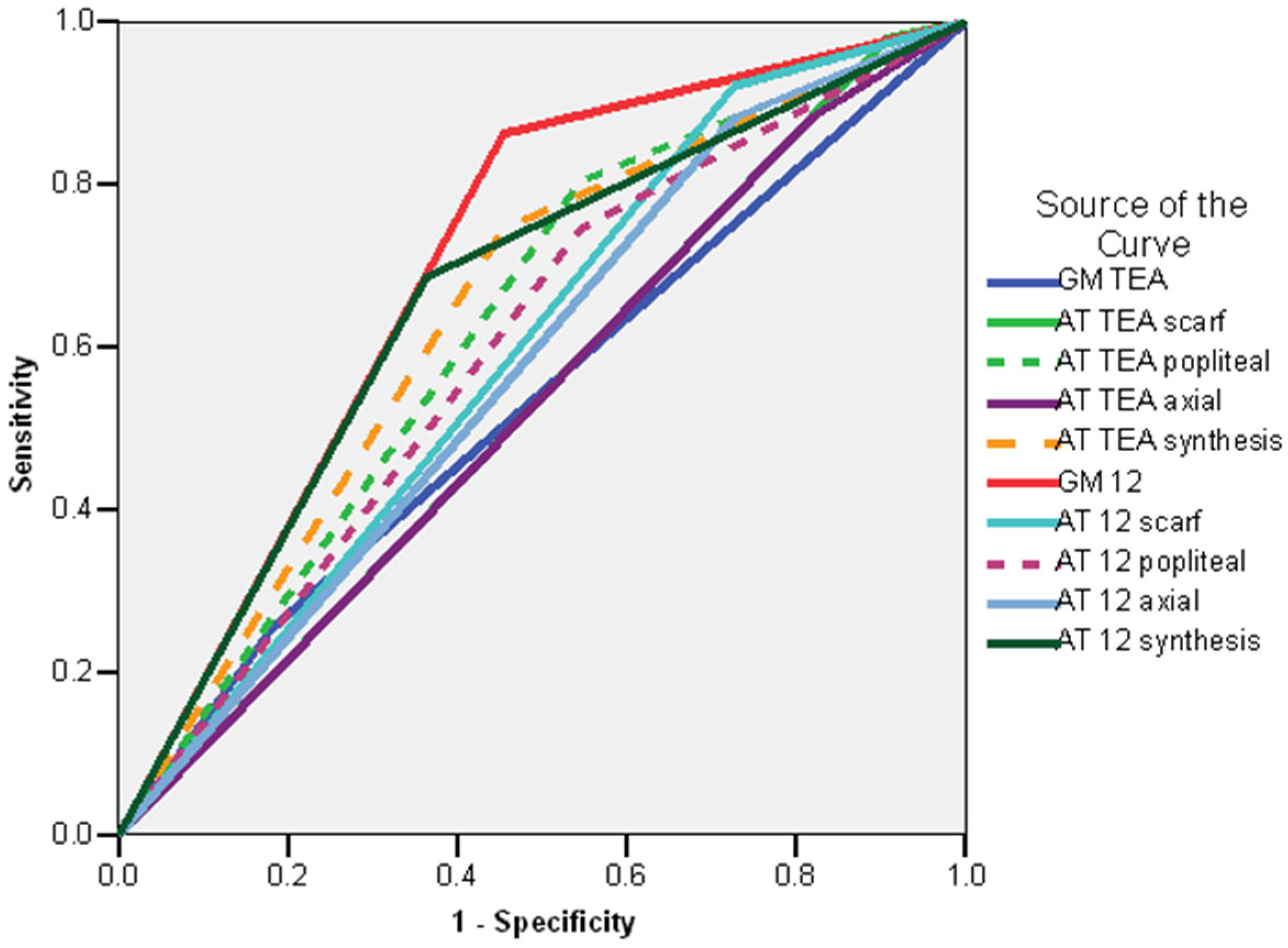

3.6. Predictive Values and Regression Models—Synthesis and Comparisons

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Main Results

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

4.3. Limitations, Strong Points, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AT | Amiel-Tison |

| ATNAT | Amiel-Tison Neurological Assessment at Term |

| ATNA | Amiel-Tison Neurological Assessment |

| B | Beta coefficient—logistic regression models |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| CA | Corrected age |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CP | Cerebral palsy |

| CS | Cramped–synchronized |

| Df | Degrees of freedom—logistic regression models |

| Exp(B) | The odds ratio for the predictor variable it is associated with |

| GA | Gestational age |

| GM | General movements |

| GMA | General movements assessment |

| GMFCS | Gross Motor Function Classification System |

| HINE | The Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PR | Poor repertoire. |

| ROC curve | Receiver Operating Characteristic curve |

| S.E. | Standard error—logistic regression models |

| Sig. | Significance—logistic regression models |

| TEA | Term equivalent age |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

Appendix A

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM TEA. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.050 | 0.311 | 11.429 | 1 | 0.001 | 2.857 | 1.555 | 5.251 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: ATTEA scarf | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.291 | 0.340 | 14.379 | 1 | 0.001 | 3.636 | 1.866 | 7.087 | |

| ATTEA scarf (abnormal) | −22.494 | 23,205.42 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | Not computed | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT TEA popliteal | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.609 | 0.447 | 12.951 | 1 | 0.001 | 5.000 | 2.081 | 12.013 | |

| ATTEA scarf (abnormal) | −21.896 | 23,205.42 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.916 | 0.707 | 1.679 | 1 | 0.195 | 0.400 | 0.100 | 1.599 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT TEA axial | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.785 | 0.490 | 13.252 | 1 | 0.001 | 5.960 | 2.279 | 15.581 | |

| ATTEA scarf (abnormal) | −21.696 | 22,890.913 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.785 | 0.726 | 1.169 | 1 | 0.280 | 0.456 | 0.110 | 1.893 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | −0.848 | 0.773 | 1.205 | 1 | 0.272 | 0.428 | 0.094 | 1.947 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT TEA synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 2.197 | 0.609 | 13.035 | 1 | 0.001 | 9.000 | 2.730 | 29.667 | |

| ATTEA scarf (abnormal) | −24.416 | 19,894.349 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | 1.386 | 1.384 | 1.003 | 1 | 0.317 | 4.000 | 0.265 | 60.325 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | 0.981 | 1.291 | 0.577 | 1 | 0.447 | 2.667 | 0.212 | 33.486 | |

| ATTEA synthesis (normal) | −3.178 | 1.644 | 3.736 | 1 | 0.053 | 0.042 | 0.002 | 1.046 | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM12. | |||||||||

| GM12 (fidgeting absent) | −1.386 | 0.645 | 4.612 | 1 | 0.032 | 0.250 | 0.071 | 0.886 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT12 scarf. | |||||||||

| GM12 (fidgeting absent) | −1.078 | 0.734 | 2.161 | 1 | 0.142 | 0.340 | 0.081 | 1.433 | |

| AT12 scarf (abnormal) | −0.922 | 1.228 | 0.564 | 1 | 0.453 | 0.398 | 0.036 | 4.412 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT12 popliteal. | |||||||||

| GM12 (fidgeting absent) | −2.911 | 1.238 | 5.532 | 1 | 0.019 | 0.054 | 0.005 | 0.616 | |

| AT12 scarf (abnormal) | −1.259 | 1.253 | 1.009 | 1 | 0.315 | 0.284 | 0.024 | 3.310 | |

| AT12 popliteal (abnormal) | 2.267 | 1.054 | 4.622 | 1 | 0.032 | 9.649 | 1.222 | 76.208 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT12 axial | |||||||||

| GM12 (fidgeting absent) | −3.430 | 1.331 | 6.639 | 1 | 0.010 | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.440 | |

| AT12 scarf (abnormal) | −0.826 | 1.305 | 0.400 | 1 | 0.527 | 0.438 | 0.034 | 5.653 | |

| AT12 popliteal (abnormal) | 2.223 | 1.058 | 4.419 | 1 | 0.036 | 9.237 | 1.162 | 73.417 | |

| AT12 axial (abnormal) | 0.872 | 0.778 | 1.256 | 1 | 0.262 | 2.391 | 0.521 | 10.985 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT12 synthesis | |||||||||

| GM12 (fidgeting absent) | −3.275 | 1.386 | 5.580 | 1 | 0.018 | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.572 | |

| AT12 scarf (abnormal) | −2.822 | 1.720 | 2.691 | 1 | 0.101 | 0.060 | 0.002 | 1.733 | |

| AT12 popliteal (abnormal) | 0.887 | 1.202 | 0.544 | 1 | 0.461 | 2.427 | 0.230 | 25.598 | |

| AT12 axial (abnormal) | −1.389 | 1.469 | 0.894 | 1 | 0.344 | 0.249 | 0.014 | 4.438 | |

| AT12 synthesis (abnormal) | 2.815 | 1.519 | 3.436 | 1 | 0.064 | 16.699 | 0.851 | 327.783 | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM TEA. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | −0.489 | 0.214 | 5.241 | 1 | 0.022 | 0.613 | 0.404 | 0.932 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT TEA SCARF. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | −0.018 | 0.244 | 0.006 | 1 | 0.940 | 0.982 | 0.609 | 1.583 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −0.470 | 0.118 | 16.005 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.625 | 0.496 | 0.787 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT TEA POPLITEAL. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 0.119 | 0.267 | 0.200 | 1 | 0.655 | 1.127 | 0.667 | 1.902 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −0.231 | 0.183 | 1.602 | 1 | 0.206 | 0.794 | 0.555 | 1.135 | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.377 | 0.243 | 2.405 | 1 | 0.121 | 0.686 | 0.426 | 1.105 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT TEA AXIAL. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 0.159 | 0.274 | 0.336 | 1 | 0.562 | 1.172 | 0.685 | 2.004 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −0.103 | 0.243 | 0.180 | 1 | 0.672 | 0.902 | 0.561 | 1.452 | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.346 | 0.248 | 1.956 | 1 | 0.162 | 0.707 | 0.436 | 1.149 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | −0.198 | 0.252 | 0.620 | 1 | 0.431 | 0.820 | 0.501 | 1.344 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT TEA synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 0.176 | 0.281 | 0.392 | 1 | 0.531 | 1.192 | 0.687 | 2.068 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −0.138 | 0.268 | 0.267 | 1 | 0.606 | 0.871 | 0.515 | 1.472 | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.257 | 0.373 | 0.473 | 1 | 0.492 | 0.774 | 0.372 | 1.608 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | −0.143 | 0.306 | 0.217 | 1 | 0.641 | 0.867 | 0.476 | 1.579 | |

| AT TEA synthesis (normal) | −0.127 | 0.402 | 0.100 | 1 | 0.751 | 0.880 | 0.400 | 1.936 | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM12. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −0.288 | 0.764 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.706 | 0.750 | 0.168 | 3.351 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT12MS. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | 0.409 | 0.901 | 0.206 | 1 | 0.650 | 1.506 | 0.258 | 8.805 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.288 | 0.764 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.706 | 1.333 | 0.298 | 5.957 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT12MI. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | 0.456 | 0.918 | 0.247 | 1 | 0.619 | 1.578 | 0.261 | 9.541 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | −0.409 | 0.901 | 0.206 | 1 | 0.650 | 0.664 | 0.114 | 3.883 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 0.815 | 0.543 | 2.258 | 1 | 0.133 | 2.260 | 0.780 | 6.548 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT12AX. | |||||||||

| GM12 (absent) | 0.288 | 0.764 | 0.142 | 1 | 0.706 | 1.333 | 0.298 | 5.957 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | −0.456 | 0.918 | 0.247 | 1 | 0.619 | 0.634 | 0.105 | 3.831 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 0.870 | 0.578 | 2.268 | 1 | 0.132 | 2.387 | 0.769 | 7.407 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | −0.171 | 0.605 | 0.079 | 1 | 0.778 | 0.843 | 0.258 | 2.760 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT12 synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | 1.000 | 0.496 | 4.060 | 1 | 0.044 | 2.717 | 1.028 | 7.184 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.165 | 1.267 | 0.017 | 1 | 0.897 | 1.179 | 0.098 | 14.124 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | −0.257 | 0.715 | 0.130 | 1 | 0.719 | 0.773 | 0.191 | 3.137 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | 0.432 | 0.501 | 0.742 | 1 | 0.389 | 1.540 | 0.577 | 4.112 | |

| AT12 synthesis(abnormal) | −0.296 | 0.792 | 0.139 | 1 | 0.709 | 0.744 | 0.157 | 3.515 | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM TEA. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 0.865 | 0.298 | 8.424 | 1 | 0.004 | 2.375 | 1.324 | 4.259 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT TEA scarf. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.073 | 0.321 | 11.145 | 1 | 0.001 | 2.923 | 1.557 | 5.487 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −22.276 | 23,205.42 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | Not computed | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT TEA popliteal. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.421 | 0.421 | 110392 | 1 | 0.001 | 4.143 | 1.815 | 9.457 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −21.608 | 23,205.42 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | Not computed | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −1.016 | 0.675 | 2.268 | 1 | 0.132 | 0.362 | 0.097 | 1.358 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT TEA axial. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.515 | 0.451 | 11.274 | 1 | 0.001 | 4.551 | 1.879 | 11.023 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −21.466 | 23,091.39 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.938 | 0.687 | 1.866 | 1 | 0.172 | 0.391 | 0.102 | 1.504 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | −0.500 | 0.759 | 0.435 | 1 | 0.510 | 0.606 | 0.137 | 2.684 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT TEA synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.872 | 0.537 | 12.146 | 1 | 0.001 | 6.500 | 2.269 | 18.624 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −24.454 | 19,564.15 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | Not computed | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | 1.386 | 1.384 | 1.003 | 1 | 0.317 | 4.000 | 0.265 | 60.325 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | 1.386 | 1.285 | 1.165 | 1 | 0.280 | 4.000 | 0.323 | 49.596 | |

| AT TEA synthesis (normal) | −30.258 | 1.614 | 4.075 | 1 | 0.044 | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.910 | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM12. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −1.386 | 0.645 | 4.612 | 1 | 0.032 | 0.250 | 0.071 | 0.886 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT12 scarf. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −1.540 | 0.815 | 3.571 | 1 | 0.050 | 0.214 | 0.043 | 1.059 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.360 | 1.095 | 0.108 | 1 | 0.742 | 1.434 | 0.168 | 12.270 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT12 popliteal. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −2.640 | 1.083 | 5.944 | 1 | 0.015 | 0.071 | 0.009 | 0.596 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.127 | 1.101 | 0.013 | 1 | 0.908 | 1.136 | 0.131 | 9.817 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 1.386 | 0.790 | 3.078 | 1 | 0.079 | 3.999 | 0.850 | 18.813 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT12 axial | |||||||||

| GM12 (absent) | −2.976 | 1.163 | 6.550 | 1 | 0.010 | 0.051 | 0.005 | 0.498 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.437 | 1.180 | 0.137 | 1 | 0.711 | 1.547 | 0.153 | 15.620 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 1.343 | 0.792 | 2.874 | 1 | 0.090 | 3.832 | 0.811 | 18.110 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | 0.613 | 0.745 | 0.678 | 1 | 0.410 | 1.846 | 0.429 | 7.943 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT12 synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | 1.000 | 0.496 | 4.060 | 1 | 0.044 | 2.717 | 1.028 | 7.184 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.165 | 1.267 | 0.017 | 1 | 0.897 | 1.179 | 0.098 | 14.124 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | −0.257 | 0.715 | 0.130 | 1 | 0.719 | 0.773 | 0.191 | 3.137 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | 0.432 | 0.501 | 0.742 | 1 | 0.389 | 1.540 | 0.577 | 4.112 | |

| AT12 synthesis(abnormal) | −0.296 | 0.792 | 0.139 | 1 | 0.709 | 0.744 | 0.157 | 3.515 | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM TEA. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.186 | 0.345 | 11.844 | 1 | 0.001 | 3.273 | 1.666 | 6.429 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT TEA SCARF. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.386 | 0.373 | 13.837 | 1 | 0.001 | 4.000 | 1.927 | 8.304 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −22.589 | 28,420.72 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | Not computed | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT TEA POPLITEAL. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.686 | 0.487 | 11.998 | 1 | 0.001 | 5.400 | 2.080 | 14.022 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −22.014 | 28,420.72 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.875 | 0.773 | 1.281 | 1 | 0.258 | 0.417 | 0.092 | 1.897 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT TEA AXIAL. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.749 | 0.511 | 11.713 | 1 | 0.001 | 5.749 | 2.112 | 15.655 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −21.918 | 28,310.09 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.830 | 0.782 | 1.128 | 1 | 0.288 | 0.436 | 0.094 | 2.017 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | −0.441 | 0.958 | 0.212 | 1 | 0.645 | 0.643 | 0.098 | 4.206 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT TEA synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 2.120 | 0.611 | 12.042 | 1 | 0.001 | 8.333 | 2.516 | 27.600 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −41.066 | 31,492.697 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | 20.805 | 19,017.791 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 1 × 109 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | 20.399 | 19,017.791 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 7 × 109 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA synthesis (normal) | −22.520 | 19,017.791 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM12. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −1.204 | 0.658 | 3.345 | 1 | 0.067 | 0.300 | 0.083 | 1.090 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT12MS. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −0.756 | 0.775 | 0.951 | 1 | 0.330 | 0.470 | 0.103 | 2.146 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | −1.170 | 1.246 | 0.882 | 1 | 0.348 | 0.310 | 0.027 | 3.568 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT12MI. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −2.377 | 1.238 | 3.689 | 1 | 0.055 | 0.093 | 0.008 | 1.050 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | −1.705 | 1.315 | 1.683 | 1 | 0.195 | 0.182 | 0.014 | 2.390 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 2.276 | 1.073 | 4.498 | 1 | 0.034 | 9.736 | 1.188 | 79.763 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT12AX. | |||||||||

| GM12 (absent) | −3.275 | 1.390 | 5.551 | 1 | 0.018 | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.577 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | −1.027 | 1.367 | 0.564 | 1 | 0.453 | 0.358 | 0.025 | 5.224 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 2.335 | 1.112 | 4.409 | 1 | 0.036 | 10.330 | 1.168 | 91.343 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | 1.645 | 1.069 | 2.366 | 1 | 0.124 | 5.179 | 0.637 | 42.117 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT12 synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −3.275 | 1.386 | 5.580 | 1 | 0.018 | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.572 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | −2.822 | 1.720 | 2.691 | 1 | 0.101 | 0.060 | 0.002 | 1.733 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 0.887 | 1.202 | 0.544 | 1 | 0.461 | 2.427 | 0.230 | 25.598 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | −1.389 | 1.469 | 0.894 | 1 | 0.344 | 0.249 | 0.014 | 4.438 | |

| AT12 synthesis(abnormal) | 4.815 | 1.519 | 3.436 | 1 | 0.046 | 16.699 | 1.851 | 327.783 | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM TEA. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.440 | 0.371 | 15.096 | 1 | 0.001 | 4.222 | 2.042 | 8.732 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT TEA scarf. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.531 | 0.390 | 15.428 | 1 | 0.001 | 4.625 | 2.154 | 9.931 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −1.531 | 1.467 | 1.090 | 1 | 0.297 | 0.216 | 0.012 | 3.833 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT TEA popliteal. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.946 | 0.535 | 13.253 | 1 | 0.001 | 7.000 | 2.455 | 19.957 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −0.811 | 1.537 | 0.279 | 1 | 0.598 | 0.444 | 0.022 | 9.032 | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −1.135 | 0.804 | 1.992 | 1 | 0.158 | 0.321 | 0.066 | 1.555 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT TEA axial. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.956 | 0.550 | 12.640 | 1 | 0.001 | 7.069 | 2.405 | 20.776 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −0.791 | 1.559 | 0.257 | 1 | 0.612 | 0.454 | 0.021 | 9.628 | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −1.127 | 0.811 | 1.931 | 1 | 0.165 | 0.324 | 0.066 | 1.588 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | −0.076 | 0.989 | 0.006 | 1 | 0.939 | 0.927 | 0.133 | 6.434 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT TEA synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.154 | 0.556 | 0.077 | 1 | 0.050 | 1.167 | 0.392 | 3.471 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −0.138 | 0.268 | 0.267 | 1 | 0.606 | 0.871 | 0.515 | 1.472 | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.257 | 0.373 | 0.473 | 1 | 0.492 | 0.774 | 0.372 | 1.608 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | −0.143 | 0.306 | 0.217 | 1 | 0.641 | 0.867 | 0.476 | 1.579 | |

| AT TEA synthesis (normal) | −0.127 | 0.402 | 0.100 | 1 | 0.751 | 0.880 | 0.400 | 1.936 | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM12. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | 0.154 | 0.556 | 0.077 | 1 | 0.782 | 1.167 | 0.392 | 3.471 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT12 scarf. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | 0.036 | 0.714 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.959 | 1.037 | 0.256 | 4.205 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.256 | 0.979 | 0.069 | 1 | 0.793 | 1.292 | 0.190 | 8.798 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT12 popliteal. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −1.044 | 0.948 | 1.212 | 1 | 0.271 | 0.352 | 0.055 | 2.259 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | −.0287 | 1.043 | 0.076 | 1 | 0.783 | 0.751 | 0.097 | 5.796 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 1.716 | 0.841 | 4.160 | 1 | 0.041 | 5.563 | 1.069 | 28.941 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT12 axial. | |||||||||

| GM12 (absent) | −1.504 | 1.060 | 2.014 | 1 | 0.156 | 0.222 | 0.028 | 1.774 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.085 | 1.101 | 0.006 | 1 | 0.938 | 1.089 | 0.126 | 9.415 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 1.741 | 0.867 | 4.033 | 1 | 0.045 | 5.702 | 1.043 | 31.183 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | 0.901 | 0.878 | 1.053 | 1 | 0.305 | 2.462 | 0.440 | 13.770 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT12 synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | 1.000 | 0.496 | 4.060 | 1 | 0.044 | 2.717 | 1.028 | 7.184 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.165 | 1.267 | 0.017 | 1 | 0.897 | 1.179 | 0.098 | 14.124 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | −0.257 | 0.715 | 0.130 | 1 | 0.719 | 0.773 | 0.191 | 3.137 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | 0.432 | 0.501 | 0.742 | 1 | 0.389 | 1.540 | 0.577 | 4.112 | |

| AT12 synthesis(abnormal) | 1.160 | 0.263 | 19.499 | 1 | 0.001 | 3.191 | 1.907 | 5.341 | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM TEA. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 0.961 | 0.326 | 8.692 | 1 | 0.003 | 2.615 | 1.380 | 4.956 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT TEA scarf. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.128 | 0.347 | 10.584 | 1 | 0.001 | 3.091 | 1.566 | 6.100 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −22.331 | 28,420.72 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | Not Computed | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT TEA popliteal. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.466 | 0.453 | 10.482 | 1 | 0.001 | 4.333 | 1.784 | 10.528 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −21.673 | 28,420.72 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.996 | 0.728 | 1.873 | 1 | 0.171 | 0.369 | 0.089 | 1.538 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT TEA axial. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.478 | 0.470 | 9.894 | 1 | 0.002 | 4.382 | 1.745 | 11.004 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −21.650 | 28,416.13 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | −0.987 | 0.735 | 1.805 | 1 | 0.179 | 0.373 | 0.088 | 1.573 | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | −0.088 | 0.951 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.926 | 0.916 | 0.142 | 5.901 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT TEA synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM TEA (abnormal) | 1.792 | 0.540 | 11.007 | 1 | 0.001 | 6.000 | 2.082 | 17.292 | |

| AT TEA scarf (abnormal) | −41.027 | 31,152.97 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA popliteal (abnormal) | 20.793 | 18,901.25 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 1 × 1010 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA axial (abnormal) | 20.793 | 18,901.25 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 1 × 1010 | 0.000 | . | |

| AT TEA synthesis (normal) | −22.584 | 18,901.25 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | |

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95.0% C.I. for EXP(B) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Variable(s) entered on step 1: GM12. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −1.204 | 0.658 | 3.345 | 1 | 0.067 | 0.300 | 0.083 | 1.090 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 2: AT12 scarf. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −1.270 | 0.845 | 2.260 | 1 | 0.133 | 0.281 | 0.054 | 1.471 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.140 | 1.101 | 0.016 | 1 | 0.899 | 1.150 | 0.133 | 9.962 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 3: AT12 popliteal. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | −2.204 | 1.085 | 4.129 | 1 | 0.042 | 0.110 | 0.013 | 0.925 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | −0.167 | 1.121 | 0.022 | 1 | 0.882 | 0.846 | 0.094 | 7.621 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 1.309 | 0.803 | 2.659 | 1 | 0.103 | 3.701 | 0.768 | 17.841 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 4: AT12 axial | |||||||||

| GM12 (absent) | −2.716 | 1.187 | 5.237 | 1 | 0.022 | 0.066 | 0.006 | 0.677 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.281 | 1.211 | 0.054 | 1 | 0.817 | 1.324 | 0.123 | 14.208 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | 1.274 | 0.811 | 2.469 | 1 | 0.116 | 3.574 | 0.730 | 17.498 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | 1.051 | 0.924 | 1.294 | 1 | 0.255 | 2.861 | 0.468 | 17.490 | |

| Variable(s) entered on step 5: AT12 synthesis. | |||||||||

| GM 12 (absent) | 1.000 | 0.496 | 4.060 | 1 | 0.044 | 2.717 | 1.028 | 7.184 | |

| AT 12 scarf (abnormal) | 0.165 | 1.267 | 0.017 | 1 | 0.897 | 1.179 | 0.098 | 14.124 | |

| AT 12 popliteal (abnormal) | −0.257 | 0.715 | 0.130 | 1 | 0.719 | 0.773 | 0.191 | 3.137 | |

| AT 12 axial (abnormal) | 0.432 | 0.501 | 0.742 | 1 | 0.389 | 1.540 | 0.577 | 4.112 | |

| AT12 synthesis(abnormal) | −0.296 | 0.792 | 0.139 | 1 | 0.709 | 0.744 | 0.157 | 3.515 | |

References

- Morgan, C.; Fetters, L.; Adde, L.; Badawi, N.; Bancale, A.; Boyd, R.N.; Chorna, O.; Cioni, G.; Damiano, D.L.; Darrah, J.; et al. Early Intervention for Children Aged 0 to 2 Years with or at High Risk of Cerebral Palsy International Clinical Practice Guideline. JAMA Pediatr. 2021, 175, 846–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palisano, E.; Rosenbaum, P.; Walter, S.; Russel, D.; Wood, E.; Galuppi, P. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krägeloh-Mann, I. Cerebral Palsy and Related Movement Disorders. In Aicardi’s Diseases of the Nervous System in Childhood, 5th ed.; Arzimanoglu, A., Ed.; Mac Keith Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 347–374. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, I.; Morgan, C.; Adde, L.; Blackman, J.; Boyd, R.; Brunstrom-Hernandez, J.; Cioni, G.; Damiano, D.; Darrah, J.; Eliasson, A.C.; et al. Early, Accurate Diagnosis and Early Intervention in Cerebral Palsy Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Dib, M.; Massaro, A.N.; Glass, P.; Aly, H. Neurodevelopmental assessment of the newborn: An opportunity for prediction of outcome. Brain Dev. 2011, 33, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, J.J.; El-Dib, M. Neurological Examination: Normal and Abnormal Features. In Volpe’s Neurology of the Newborn, 7th ed.; Volpe, J.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 293–323. [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington, C.S. The Integrative Action of the Nervous System; Yale University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz, L.M.S.; Dubowitz, V.; Mercuri, E. The Neurological Assessment of the Pre-Term and Full-Term Newborn Infant, 2nd ed.; Mac Keith Press: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Amiel-Tison, C. Update of the Amiel-Tison Neurological assessment for the term neonate or at 40 weeks corrected age. Pediatr. Neurol. 2002, 27, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, J.; Gahagan, S.; Amiel-Tison, C. The Amiel-Tison neurological assessment at term: Conceptual and methodological continuity in the course of follow-up. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2005, 11, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prechtl, H.F.R. The Optimality Concept. Early Hum. Dev. 1980, 4, 201–205. [Google Scholar]

- Amiel Tison, C.; Gosselin, J. Pathologie Neurologique Périnatale et Ses Conséquences; Elsevier Masson: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin, J.; Amiel-Tison, C. Évaluation Neurologique de la Naissance à 6 Ans, 2nd ed; Masson: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deschenes, G.M.; Gosselin, J.; Couture, M.; Lachance, C. Interobserver Reliability of the Amiel-Tison Neurological Assessment at Term. Pediatr. Neurol. 2004, 30, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paro-Panjan, D.; Neubauer, D.; Kodric, J.; Bratanic, B. Amiel-Tison Neurological Assessment at term age: Clinical application, correlation with other methods, and outcome at 12 to 15 months. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2005, 47, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.; Hope, P.L.; Hamilton, P.; Costello, A.M.; Baudin, J.; Bradford, B.; Amiel Tison, C.; Reynolds, E.O.R. Prediction in very preterm infants of satisfactory neurodevelopmental progress at 12 months. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1988, 30, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einspieler, C.; Prechtl, H.F.R. Prechtl’s assessment of General Movements: A Diagnostic Tool for the Functional Assessment of the Young Nervous System. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2005, 11, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einspieler, C.; Prechtl, H.F.; Bos, A.F.; Ferrari, F.; Cioni, G. Prechtl’s Method on the Qualitative Assessment of General Movements in Preterm, Term and Young Infants; Mac Keith Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yuste, R.; MacLean, J.N.; Smith, J.; Lansner, A. The cortex as a central pattern generator. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadders-Algra, M. Putative neural substrate of normal and abnormal general movements. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2007, 31, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadders-Algra, M. Neural substrate and clinical significance of general movements: An update. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prechtl, H.F.R.; Einspieler, C.; Cioni, G.; Bos, A.F.; Ferrari, F.; Sontheimer, D. An early marker for neurological deficits after perinatal brain lesions. Lancet 1997, 349, 1361–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.; Cioni, G.; Einspieler, C.; Roversi, M.F.; Bos, A.F.; Paolicelli, P.B.; Ranzi, A.; Prechtl, H.F.R. Cramped-Synchronized General Movements in Preterm Infants as an Early Marker for Cerebral Palsy. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einspieler, C.; Bos, A.F.; Krieber-Tomantschger, M.; Alvarado, E.; Barbosa, V.M.; Bertoncelli, N.; Burger, M.; Chorna, O.; Del Secco, S.; DeRegnier, R.A.; et al. Cerebral Palsy: Early Markers of Clinical Phenotype and Functional Outcome. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjan, D.P.; Susteric, B.; Neubauer, D. Comparison of two methods of neurologic assessment in infants. Pediatr. Neurol. 2005, 33, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahlman, N.; Hartel, C.; Knopp, B.; Kiecksee, H.; Thyn, U. Predictive Value of Neurodevelopmental Assessment versus Evaluation of General Movements for Outcome in Preterm Infants with Birth Weights <1500 g. Neuropediatrics 2007, 38, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, D.M.M.; Guzzetta, A.; Scoto, M.; Cioni, M.; Patusi Mazzone, D.; Romeo, M.G. Early neurologic assessment in preterm-infants: Integration of traditional neurologic examination and observation of general movements. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2008, 12, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma AI (Coord). (Ed.) Urmărirea Nou-Născutului cu Risc Pentru Sechele Neurologice și de Dezvoltare, Follow Up Guidelines 2025; Ghidul 13, Colectia Ghiduri Clinice Pentru Neonatologie; Ministerul Sănătății: Bucharest, Romania. Available online: https://ms.ro/media/documents/Ghid_privind_urm%C4%83rirea_nou-n%C4%83scutului_cu_risc_pentru_sechele_neurologice_%C5%9Fi_de_WLpMtDL.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Woodward, L.J.; Huppi, P.S. Neurodevelopmental Follow-Up of High-Risk Infants. In Volpe’s Neurology of the Newborn, 6th ed.; Volpe, J.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 360–377. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, M.C.; Darrah, J. Motor Assessment of the Developing Infant; W.B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Storvold, G.V.; Aarethun, K.; Bratberg, G.H. Age for onset of walking and prewalking strategies. Early Hum. Dev. 2013, 89, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax, M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2007, 49, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCPE Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe. A collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2000, 42, 816–824. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Sterne, J.A.C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Version 5.2.0; Higgins, J.P.T., Churchill, R., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M.S., Eds.; Cochrane: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bendrea, C. Biostatistică. Elemente de Teorie și Modelare Probabilistică; Universitatea “Dunărea de Jos”: Galați, Romania, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Swinscow, T.D.V. Statistics at Square One, 9th ed.; BMJ Publishing Group: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Einspieler, C.; Bos, A.F.; Libertus, M.E.; Marschik, P.B. The General Movement Assessment Helps Us to Identify Preterm Infants at Risk for Cognitive Dysfunction. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolow, M.; Adde, L.; Klimont, L.; Pilarska, E.; Einspieler, C. Early intervention and its short-term effect on the temporal organization of fidgety movements. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 151, 105191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, S.; Goldsmith, S.; Webb, A.; Ehlinger, V.; Hollung, S.J. Global prevalence of cerebral palsy: A systematic analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2022, 64, 1494–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veber Fogh, M.; Greisen, G.; Dalsgaard Clausen, T.; Krebs, L.; Larsen, M.L.; Hoei-Hansen, C.E. Increasing prevalence of cerebral palsy in children born very preterm in Denmark. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2025, 67, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel Tison, C. L’infirmité Motrice D’origine Cérébrale, 2nd ed.; Masson: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney, H.C.; Volpe, J.J. Encephalopathy of Prematurity. Neuropathology. In Volpe’s Neurology of the Newborn, 6th ed.; Volpe, J.J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 389–404. [Google Scholar]

- Marschik, P.; Soloveichick, M.; Windpassinger, C.; Einspieler, C. General Movements in genetic disorders: A first look into Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2013, 18, 280–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, W.; Anderson, P.J.; Battin, M.; Bowen, J.R.; Brown, N.; Callanan, C.; Campbell, C.; Chandler, S.; Cheong, J.; Darlow, B.; et al. Long term follow up of high risk children: Who, why and how? BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.A.; Shetty, S.; Wilson, B.A.; Huang, A.J.; Jin, S.C.; Smithers-Sheedy, H.; Fahey, M.C.; Kruer, M.C. Insights from Genetic Studies of Cerebral Palsy. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 625428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzing, A.M.; Eklund, E.; de Koning, T.J.; Eggink, H. Clinical Characteristics Suggestive of a Genetic Cause in Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. Pediatr. Neurol. 2024, 153, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TEA | 12 Weeks CA | 7 Months CA | 12 Months CA | 18 Months CA | 24 Months CA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GMA | GMA | - | - | - | - |

| ATNAT | Amiel-Tison 0–6 years | Amiel-Tison 0–6 years | Amiel-Tison 0–6 years | Amiel-Tison 0–6 years | Amiel-Tison 0–6 years |

| Optimal | Non-Optimal/Abnormal | |

|---|---|---|

| Examination at TEA | ||

| Axial tone—raise to sit and reverse maneuver | Easy to obtain—in axis | Raise to sit—contraction of muscles, but no passage/no response Reverse—back-to-back—excessive response/no response |

| Upper limbs—scarf sign | The elbow does not touch the midline | The elbow can be displaced below the midline |

| Lower limbs—popliteal angle | 70–90° | >100° |

| Examination at 12 weeks CA | ||

| Axial tone—head control | Maintenance of the head in the axis of the boy for at least 15 s |

|

| Upper limbs—scarf sign | The elbow can be displaced below the midline but not over the opposite mammary line | The elbow does not touch the midline—hypertonia The elbow can be displaced all the way to the opposite shoulder, or there may be no resistance at all—hypotonia |

| Lower limbs—popliteal angle | ≥90° | <90° |

| 12 Weeks CA GM | GM TEA | Chi-Square Test Likelihood Ratio p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS (n = 17) | PR (n = 37) | Normal (n = 16) | All (n = 70) | ||

| Absent fidgety | 6 (35.3%) | 9 (24.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (21.4%) | <0.008 |

| Present fidgety | 11 (64.7%) | 28 (75.7%) | 16 (100.0%) | 55 (78.6%) | |

| CP (n = 15) | Non-CP (n = 55) | Chi-Square Test Likelihood Ratio p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Movements | |||

| GM TEA | <0.103 | ||

| CS | 6 (40.0%) | 11 (20.0%) | |

| PC | 8 (53.3%) | 29 (52.7%) | |

| Normal | 1 (6.7%) | 15 (27.3%) | |

| GM 12-week CA | <0.001 | ||

| Absent | 12 (80.0%) | 3 (5.5%) | |

| fidgety | 3 (20.0%) | 52 (94.5%) | |

| Amiel-Tison Examinations | |||

| AT TEA scarf | <0.008 | ||

| Hypertonia | 2 (13.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Hypotonia | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Normal | 12 (80.0%) | 55 (100.0%) | |

| AT TEA popliteal | <0.013 | ||

| Hypotonia | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Hypertonia | 7 (46.7%) | 10 (18.2%) | |

| Normal | 7 (46.7%) | 45 (81.8%) | |

| AT TEA axial | <0.014 | ||

| Hypotonia | 4 (26.7%) | 7 (12.7%) | |

| Hypertonia | 2 (12.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Normal | 6 (60.0%) | 48 (87.3%) | |

| AT40 synthesis | <0.003 | ||

| Optimal | 5 (33.3%) | 42 (76.4%) | |

| Non-optimal | 10 (67.3%) | 13 (23.6%) | |

| AT12 scarf | <0.001 | ||

| Normal | 9 (60.0%) | 54 (98.2%) | |

| Abnormal | 6 (40.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | |

| AT12 popliteal | <0.001 | ||

| Hypertonia | 10 (66.7%) | 11 (20.0%) | |

| Normal | 5 (33.3%) | 44 (80.0%) | |

| AT12 axial | <0.035 | ||

| Hypotonia | 5 (33.3%) | 7 (12.7%) | |

| Hypertonia | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Normal | 9 (60.0%) | 48 (87.3%) | |

| AT12 synthesis | <0.001 | ||

| Optimal | 3 (20.0%) | 39 (70.9%) | |

| Non-optimal | 12 (80.0%) | 16 (29.1%) | |

| Sitting Delayed (n = 15) | Sitting On Time (n = 55) | Chi-Square Test Likelihood Ratio p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Movements | |||

| GM 40 | <0.668 | ||

| Cs | 5 (33.3%) | 12 (21.8%) | |

| Pr | 7 (46.7%) | 30 (54.5%) | |

| Normal | 3 (20.0%) | 13 (23.6%) | |

| GM 12 | <0.002 | ||

| Absent | 8 (53.3%) | 7 (12.7%) | |

| Fidgety | 7 (46.7%) | 48 (87.3%) | |

| Amiel-Tison Examinations | |||

| AT TEA scarf | <0.133 | ||

| Hypertonia | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Hypotonia | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Normal | 13 (86.7%) | 44 (98.2%) | |

| AT TEA popliteal | <0.049 | ||

| Hypotonia | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Hypertonia | 6 (40.0%) | 11 (20.0%) | |

| Normal | 8 (53.3%) | 44 (80.0%) | |

| AT TEA axial | <0.272 | ||

| Hypotonia | 4 (26.7%) | 7 (12.7%) | |

| Hypertonia | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (1.8%) | |

| Normal | 10 (66.7%) | 47 (85.5%) | |

| AT40 synthesis | <0.058 | ||

| Optimal | 7 (46.7%) | 40 (72.7%) | |

| Non-optimal | 8 (53.3%) | 15 (27.3%) | |

| AT12 scarf | <0.163 | ||

| Normal | 12 (80.0%) | 51 (92.7%) | |

| Abnormal | 3 (20.0%) | 4 (7.3%) | |

| AT12 popliteal | <0.104 | ||

| Hypertonia | 7 (46.7%) | 14 (25.5%) | |

| Normal | 8 (53.3%) | 41 (74.5%) | |

| AT12 axial | <0.035 | ||

| Hypotonia | 5 (33.3%) | 7 (12.7%) | |

| Hypertonia | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Normal | 9 (60.0%) | 48 (87.3%) | |

| AT12 synthesis | <0.019 | ||

| Optimal | 5 (33.3%) | 37 (67.3%) | |

| Non-optimal | 10 (66.7%) | 18 (32.7%) | |

| Walking Delayed/Absent (n = 18) | Walking On Time (n = 52) | Chi-Square Test Likelihood Ratio p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| General movements | |||

| GM 40 | <0.160 | ||

| CS | 7 (38.9%) | 10 (19.2%) | |

| PR | 9 (50.0%) | 28 (53.8%) | |

| Normal | 2 (11.1%) | 14 (26.9%) | |

| GM 12 | <0.001 | ||

| Absent | 12 (66.7%) | 3 (5.8%) | |

| Fidgety | 6 (33.3%) | 49 (94.2%) | |

| Amiel-Tison’s examinations | |||

| AT TEA scarf | <0.014 | ||

| Hypertonia | 2 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Hypotonia | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Normal | 15 (100.0%) | 52 (100.0%) | |

| AT TEA popliteal | <0.015 | ||

| Hypotonia | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Hypertonia | 8 (44.4%) | 9 (17.3%) | |

| Normal | 9 (50.0%) | 43 (82.7%) | |

| AT TEA axial | <0.035 | ||

| Hypotonia | 4 (22.2%) | 7 (13.5%) | |

| Hypertonia | 2 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Normal | 12 (66.7%) | 45 (86.5%) | |

| AT40 synthesis | <0.004 | ||

| Optimal | 7 (38.9%) | 40 (76.9%) | |

| Non-optimal | 11 (61.1%) | 12 (23.1%) | |

| AT12 scarf | <0.010 | ||

| Normal | 13 (72.2%) | 50 (96.2%) | |

| Abnormal | 5 (27.8%) | 2 (3.8%) | |

| AT12 popliteal | <0.002 | ||

| Hypertonia | 11 (61.1%) | 10 (19.2%) | |

| Normal | 7 (38.9%) | 42 (80.8%) | |

| AT12 axial | <0.027 | ||

| Hypotonia | 6 (33.3%) | 6 (11.5%) | |

| Hypertonia | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Normal | 11 (84.7%) | 46 (88.5%) | |

| AT12 synthesis | <0.001 | ||

| Optimal | 4 (22.2%) | 38 (73.1%) | |

| Non-optimal | 14 (77.8%) | 14 (26.9%) | |

| AT TEA Results | GM Patterns | Chi-Square Test Likelihood Ratio p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS (n = 17) | PR (n = 37) | Normal (n = 16) | All (n = 70) | ||

| AT TEA scarf | <0.366 | ||||

| Hypertonia | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Hypotonia | 1 (5.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | |

| Normal | 15 (88.2%) | 36 (97.3%) | 16 (100.0%) | 67 (95.7%) | |

| AT TEA popliteal | <0.001 | ||||

| Hypotonia | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | |

| Hypertonia | 10 (58.8%) | 7 (18.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 17 (24.3%) | |

| Normal | 7 (41.2%) | 29 (78.4%) | 16 (100.0%) | 52 (74.3%) | |

| AT TEA axial | <0.015 | ||||

| Hypotonia | 3 (17.6%) | 8 (21.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (15.7%) | |

| Hypertonia | 2 (11.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.9%) | |

| Normal | 12 (70.6%) | 29 (78.4%) | 16 (100.0%) | 57 (81.4%) | |

| ATTEA synthesis | <0.001 | ||||

| Optimal | 5 (29.4%) | 26 (70.3%) | 16 (100.0%) | 47 (67.1%) | |

| Non-optimal | 12 (70.6%) | 11 (29.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 23 (32.9%) | |

| AT12 | GM 12 | Chi-Square Test Likelihood Ratio p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (n = 15) | Fidgety (n = 55) | All (n = 70) | ||

| AT12 scarf | <0.001 | |||

| Normal | 9 (60.0%) | 54 (98.2%) | 63 (90.0%) | |

| Abnormal | 6 (40.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 7 (10.0%) | |

| AT12 popliteal | <0.001 | |||

| Hypertonia | 12 (80.0%) | 9 (16.4%) | 21 (30.0%) | |

| Normal | 3 (20.0%) | 46 (83.6%) | 49 (70.0%) | |

| AT12 AX | <0.035 | |||

| Hypotonia | 5 (33.3%) | 7 (12.7%) | 12 (17.1%) | |

| Hypertonia | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | |

| Normal | 9 (60.0%) | 48 (87.3%) | 57 (81.4%) | |

| AT12 synthesis | <0.001 | |||

| Optimal | 2 (13.3%) | 40 (72.7%) | 42 (60.0%) | |

| Non-optimal | 13 (86.7%) | 14 (27.3%) | 28 (40.0%) | |

| CP (n = 11) | Non-CP (n = 51) | Chi-Square Test p | OR | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM TEA | <0.034 | - | - | ||

| Abnormal | 11 (100.0%) | 36 (70.6%) | |||

| Normal | 0 (0.0%) | 15 (29.4%) | |||

| AT TEA scarf | <0.029 | 6.67 | 3.65–12.18 | ||

| Abnormal | 2 (18.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Normal | 9 (81.8%) | 51 (100.0%) | |||

| AT TEA popliteal | <0.018 | 5.60 | 1.40–22.44 | ||

| Abnormal | 6 (54.5%) | 9 (17.6%) | |||

| Normal | 5 (45.5%) | 42 (82.4%) | |||

| AT TEA axial | <0.142 | 3.45 | 0.69–17.37 | ||

| Abnormal | 3 (27.3%) | 5 (9.8%) | |||

| Normal | 8 (72.7%) | 46 (90.2%) | |||

| AT TEA synthesis | <0.002 | 9.70 | 2.20–42.82 | ||

| Non-optimal | 8 (72.7%) | 11 (21.6%) | |||

| Optimal | 3 (27.3%) | 40 (78.4%) | |||

| GM 12 | <0.001 | 160.0 | 15.05–1700.5 | ||

| Absent | 10 (90.9%) | 3 (5.9%) | |||

| Fidgety | 1 (9.1%) | 48 (94.1%) | |||

| AT 12 scarf | <0.001 | 60.0 | 5.97–603.25 | ||

| Abnormal | 6 (54.5%) | 1 (2.0%) | |||

| Normal | 5 (45.5%) | 50 (98.0%) | |||

| AT 12 popliteal | <0.001 | 10.93 | 2.45–48.81 | ||

| Abnormal | 8 (72.7%) | 10 (19.6%) | |||

| Normal | 3 (27.3%) | 41 (80.4%) | |||

| AT 12 axial | <0.191 | 2.81 | 0.58–13.61 | ||

| Abnormal | 3 (27.3%) | 6 (11.8%) | |||

| Normal | 8 (72.7%) | 45 (88.2%) | |||

| AT 12 synthesis | <0.001 | 11.89 | 2.28–61.99 | ||

| Non-optimal | 9 (81.8%) | 14 (27.5%) | |||

| Optimal | 2 (18.2%) | 37 (72.5%) |

| Delayed (n = 11) | Sitting on Time (n = 51) | Chi-Square Test p | OR | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM TEA | <0.469 | 1.54 | 0.29–8.07 | ||

| Abnormal | 9 (81.8%) | 38 (74.5%) | |||

| Normal | 2 (18.2%) | 13 (25.5%) | |||

| AT TEA scarf | <0.326 | 5.00 | 0.29–86.76 | ||

| Abnormal | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (2.0%) | |||

| Normal | 10 (90.9%) | 50 (98.0%) | |||

| AT TEA popliteal | <0.081 | 3.42 | 0.87–13.49 | ||

| Abnormal | 5 (45.5%) | 10 (19.6%) | |||

| Normal | 6 (54.5%) | 41 (80.4%) | |||

| AT TEA axial | <0.435 | 1.67 | 0.29–9.62 | ||

| Abnormal | 2 (18.2%) | 6 (11.8%) | |||

| Normal | 9 (81.8%) | 45 (88.2%) | |||

| AT TEA synthesis | <0.066 | 3.51 | 0.92–13.44 | ||

| Non-optimal | 6 (54.5%) | 13 (25.5%) | |||

| Optimal | 5 (45.5%) | 38 (74.5%) | |||

| GM 12 | <0.007 | 7.54 | 1.81–31.52 | ||

| Absent fidgety | 6 (54.5%) | 7 (13.7%) | |||

| Fidgety | 5 (45.5%) | 44 (87.3%) | |||

| AT 12 scarf | <0.099 | 4.41 | 0.83–23.50 | ||

| Abnormal | 3 (27.3%) | 4 (7.8%) | |||

| Normal | 8 (72.7%) | 47 (92.2%) | |||

| AT 12 popliteal | <0.168 | 2.44 | 0.64–9.34 | ||

| Abnormal | 5 (45.5%) | 13 (25.5%) | |||

| Normal | 6 (54.5%) | 38 (74.5%) | |||

| AT 12 axial | <0.191 | 2.81 | 0.58–13.61 | ||

| Abnormal | 3 (27.3%) | 6 (11.8%) | |||

| Normal | 8 (72.7%) | 45 (88.2%) | |||

| AT 12 synthesis | <0.048 | 3.83 | 0.98–14.97 | ||

| Non-optimal | 7 (63.6%) | 16 (31.4%) | |||

| Optimal | 4 (36.4%) | 35 (68.6%) |

| Walking Delayed (n = 14) | Walking on Time (n = 48) | Chi-Square Test p | OR | CI 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM TEA | <0.084 | 5.35 | 0.64–44.91 | ||

| Abnormal | 13 (92.9%) | 34 (70.8%) | |||

| Normal | 1 (7.1%) | 14 (29.2%) | |||

| AT TEA scarf | <0.048 | 5.00 | 3.01–8.29 | ||

| Abnormal | 2 (14.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Normal | 12 (85.7%) | 48 (100.0%) | |||

| AT TEA popliteal | <0.017 | 5.00 | 1.37–18.23 | ||

| Abnormal | 7 (50.0%) | 8 (16.7%) | |||

| Normal | 7 (50.0%) | 40 (83.3%) | |||

| AT TEA axial | <0.253 | 2.35 | 0.48–11.35 | ||

| Abnormal | 3 (21.4%) | 5 (10.4%) | |||

| Normal | 11(78.6%) | 43 (89.6%) | |||

| AT TEA synthesis | <0.003 | 6.84 | 1.87–25.01 | ||

| Abnormal | 9 (64.3%) | 10 (20.8%) | |||

| Normal | 5 (35.7%) | 38 (79.2%) | |||

| GM 12 | <0.001 | 37.50 | 7.23–194.54 | ||

| Absent fidgety | 10 (71.4%) | 3 (6.3%) | |||

| Present fidgety | 4 (28.6%) | 45 (93.8%) | |||

| AT 12 scarf | <0.005 | 12.78 | 2.14–76.43 | ||

| Abnormal | 5 (35.7%) | 2 (4.28%) | |||

| Normal | 9 (64.3%) | 46 (94.8%) | |||

| AT 12 popliteal | <0.002 | 7.80 | 2.10–28.96 | ||

| Abnormal | 9 (64.3%) | 9 (18.8%) | |||

| Normal | 5 (35.7%) | 39 (81.3%) | |||

| AT 12 axial | <0.106 | 3.44 | 0.78–15.17 | ||

| Abnormal | 4 (28.6%) | 5 (10.4%) | |||

| Normal | 10 (71.4%) | 43 (89.6%) | |||

| AT 12 synthesis | <0.001 | 11.00 | 2.62–46.15 | ||

| Non-optimal | 11(78.6%) | 12 (25.0%) | |||

| Optimal | 3 (21.4%) | 36 (75.0%) |

| CP—Whole Group | CP—Preterm | Delayed Sitting—Whole Group | Delayed Sitting—Preterm | Delayed/Absent Walking—Whole Group | Delayed/Absent Walking—Preterm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM TEA | ||||||

| AT TEA scarf | ||||||

| AT TEA popliteal | ||||||

| AT TEA axial | ||||||

| AT TEA synthesis | ||||||

| GM 12 weeks CA | ||||||

| AT 12 weeks CA scarf | ||||||

| AT 12 weeks CA popliteal | ||||||

| AT 12 weeks CA axial | ||||||

| AT 12 weeks CA synthesis |

Not predictive;

Not predictive;  Predictive.

Predictive.| CP—Whole Group | CP—Preterm | Delayed Sitting—Whole Group | Delayed Sitting—Preterm | Delayed/Absent Walking—Whole Group | Delayed/Absent Walking—Preterm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exams at TEA | GM abnormal | GM abnormal | GM abnormal | GM abnormal | GM abnormal | |

| Exams at 12 weeks CA | GM 12—absent fidgety Model 3: absent Fidgety + abnormal scarf + abnormal popliteal | GM 12—absent fidgety Model 3 Absent fidgety + abnormal scarf + abnormal popliteal Model 5 Absent fidgety + abnormal scarf + abnormal popliteal + abnormal axial + abnormal synthesis | GM 12—absent fidgety | Model 3 Absent fidgety + abnormal scarf + abnormal popliteal Model 5 Absent fidgety + abnormal scarf + abnormal popliteal + abnormal axial + abnormal synthesis | GM 12—absent fidgety | GM 12—absent fidgety. |

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole group | |||||

| Absent fidgety 12 weeks CA | 80% | 94.55% | 80% | 94.55% | 0.873 |

| AT exam at TEA synthesis—non-optimal | 66.66% | 76.36% | 43.47% | 89.36% | 0.715 |

| AT exam at 12 weeks—synthesis—non-optimal | 80% | 70.90% | 42.85% | 92.85% | 0.755 |

| Preterm infants subgroup | |||||

| Absent fidgety 12 weeks CA | 90.9% | 94.11% | 76.92% | 97.95% | 0.925 |

| AT exam at TEA synthesis—non-optimal | 72.72% | 78.43% | 42.1% | 93.02% | 0.756 |

| AT exam at 12 weeks—synthesis—non-optimal | 81.81% | 72.54% | 39.13% | 94.87% | 0.772 |

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole group | |||||

| Absent fidgety 12 weeks CA | 53.3% | 82.72% | 53.3% | 82.72% | 0.804 |

| AT exam at 12 weeks—synthesis—non-optimal | 66.66% | 67.27% | 35.71% | 88.09% | 0.754 |

| Preterm infants subgroup | |||||

| Absent fidgety 12 weeks CA | 54.54% | 86.27% | 46.15% | 89.79% | 0.704 |

| AT exam at 12 weeks—synthesis—non-optimal | 63.63% | 68.62% | 30.43% | 89.74% | 0.661 |

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole group | |||||

| Absent fidgety 12 weeks CA | 66.66% | 94.23% | 80% | 89.09% | 0.804 |

| AT exam at TEA synthesis—non-optimal | 61.11% | 76.92% | 47.82% | 85.10% | 0.690 |

| AT exam at 12 weeks—synthesis—non-optimal | 77.77% | 73.07% | 50% | 90.47% | 0.754 |

| Preterm infants subgroup | |||||

| Absent fidgety 12 weeks CA—non-optimal | 71.42% | 93.75% | 76.92% | 91.83% | 0.826 |

| AT exam at TEA synthesis | 64.28% | 79.16% | 47.36% | 88.37% | 0.717 |

| AT exam at 12 weeks—synthesis—non-optimal | 78.56% | 75% | 47.82% | 92.3% | 0.768 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Toma, A.I.; Dima, V.; Rusu, L.; Necula, A.; Stoiciu, R.P.; Andrășoaie, L.; Mirea, A.; Bivoleanu, A.R. General Movements Assessment and Amiel-Tison Neurologic Examination in Neonates and Infants: Correlations and Prognostic Values Regarding Neuromotor Outcomes. Life 2026, 16, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010081

Toma AI, Dima V, Rusu L, Necula A, Stoiciu RP, Andrășoaie L, Mirea A, Bivoleanu AR. General Movements Assessment and Amiel-Tison Neurologic Examination in Neonates and Infants: Correlations and Prognostic Values Regarding Neuromotor Outcomes. Life. 2026; 16(1):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010081

Chicago/Turabian StyleToma, Adrian Ioan, Vlad Dima, Lidia Rusu, Andreea Necula, Roxana Pavalache Stoiciu, Larisa Andrășoaie, Andrada Mirea, and Anca Roxana Bivoleanu. 2026. "General Movements Assessment and Amiel-Tison Neurologic Examination in Neonates and Infants: Correlations and Prognostic Values Regarding Neuromotor Outcomes" Life 16, no. 1: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010081

APA StyleToma, A. I., Dima, V., Rusu, L., Necula, A., Stoiciu, R. P., Andrășoaie, L., Mirea, A., & Bivoleanu, A. R. (2026). General Movements Assessment and Amiel-Tison Neurologic Examination in Neonates and Infants: Correlations and Prognostic Values Regarding Neuromotor Outcomes. Life, 16(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010081