Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas in a Long-Term Survivor of Childhood ALL and HSCT—A Call for Dermatologic Vigilance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Literature Search Strategy

2.3.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Human studies

- English language

- Relevance to HSCT survivors or BCC molecular pathogenesis

- Q1–Q2 dermatology, oncology, hematology, or molecular medicine journals

- Case reports, cohort studies, mechanistic studies, or reviews

- Clinical studies, meta-analyses, and experimental reports addressing molecular pathways, diagnostic innovations, or management strategies in BCC or post-transplant skin cancer;

- Literature concerning survivorship after childhood ALL or HSCT; and

- Articles discussing palliative care or psychosocial outcomes in pediatric oncology.

- Animal-only studies

- Conference abstracts

- Articles without relevance to keratinocyte carcinomas or survivorship

- Non-peer-reviewed sources

- Case reports lacking histopathological confirmation

- Experimental data unrelated to skin malignancy mechanisms.

2.3.3. Analytical Framework

- Epidemiologic and clinical risk factors for cutaneous SMNs;

- Molecular and genetic pathways implicated in BCC pathogenesis post-radiation or immunosuppression;

- Diagnostic and dermoscopic innovations, including digital monitoring and AI-based tools; and

- Therapeutic and preventive strategies within a precision-dermatology framework.

2.4. Data Synthesis and Validation

2.5. Scientific Integrity and Originality Statement

3. Case Presentation

3.1. Patient History and Background

3.2. HSCT Details

- •

- Donor: HLA-matched sibling;

- •

- Conditioning regimen: Fractionated TBI (total 12 Gy) + cyclophosphamide;

- •

- Acute GvHD: Grade II (skin + GI), resolved with corticosteroids;

- •

- Chronic GvHD: None;

- •

- Infections: CMV reactivation (treated), no invasive fungal disease;

- •

- TA-TMA: Absent;

- •

- Immunosuppression: cyclosporine for 9 months.

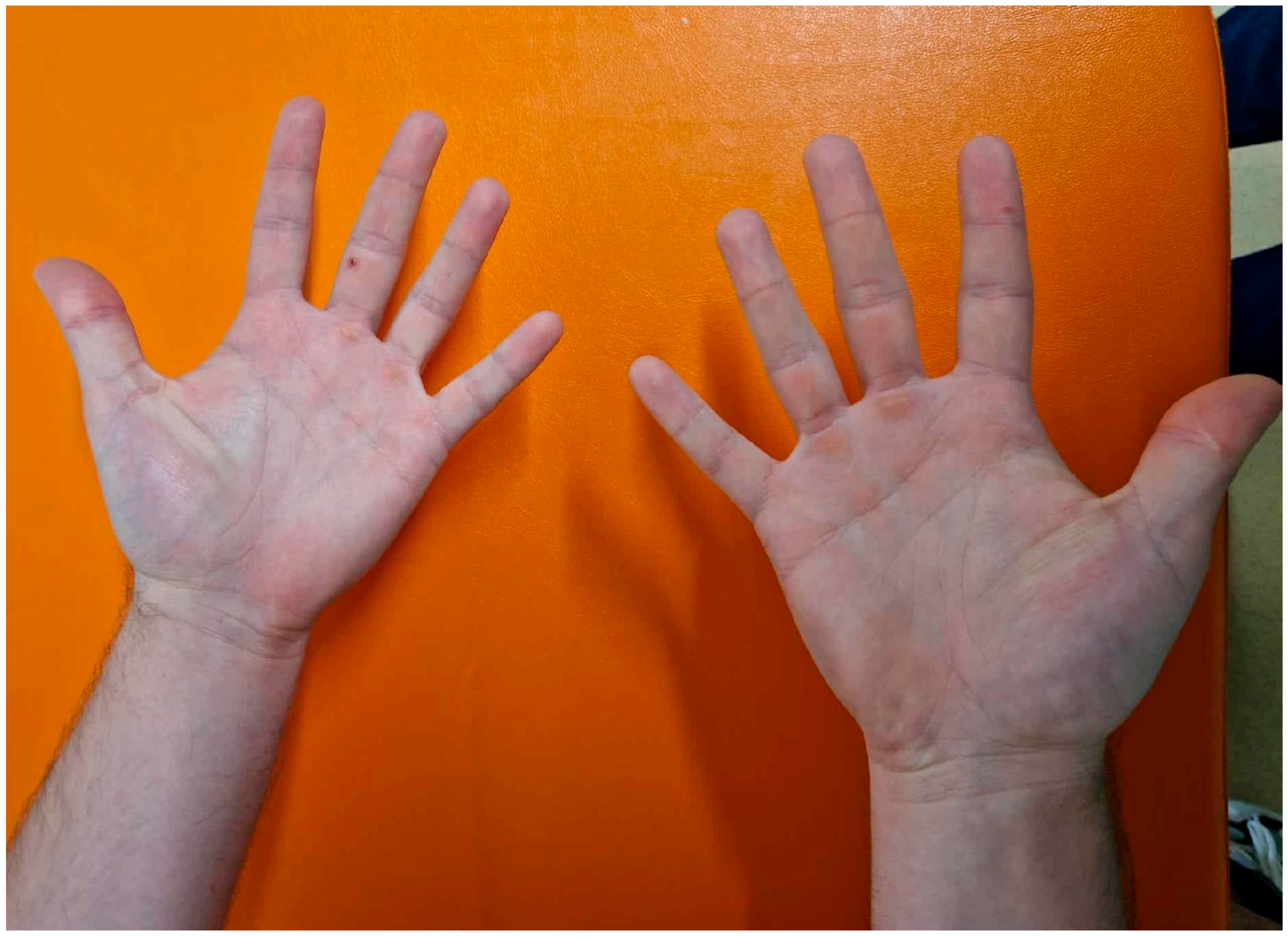

3.3. Dermatologic Findings

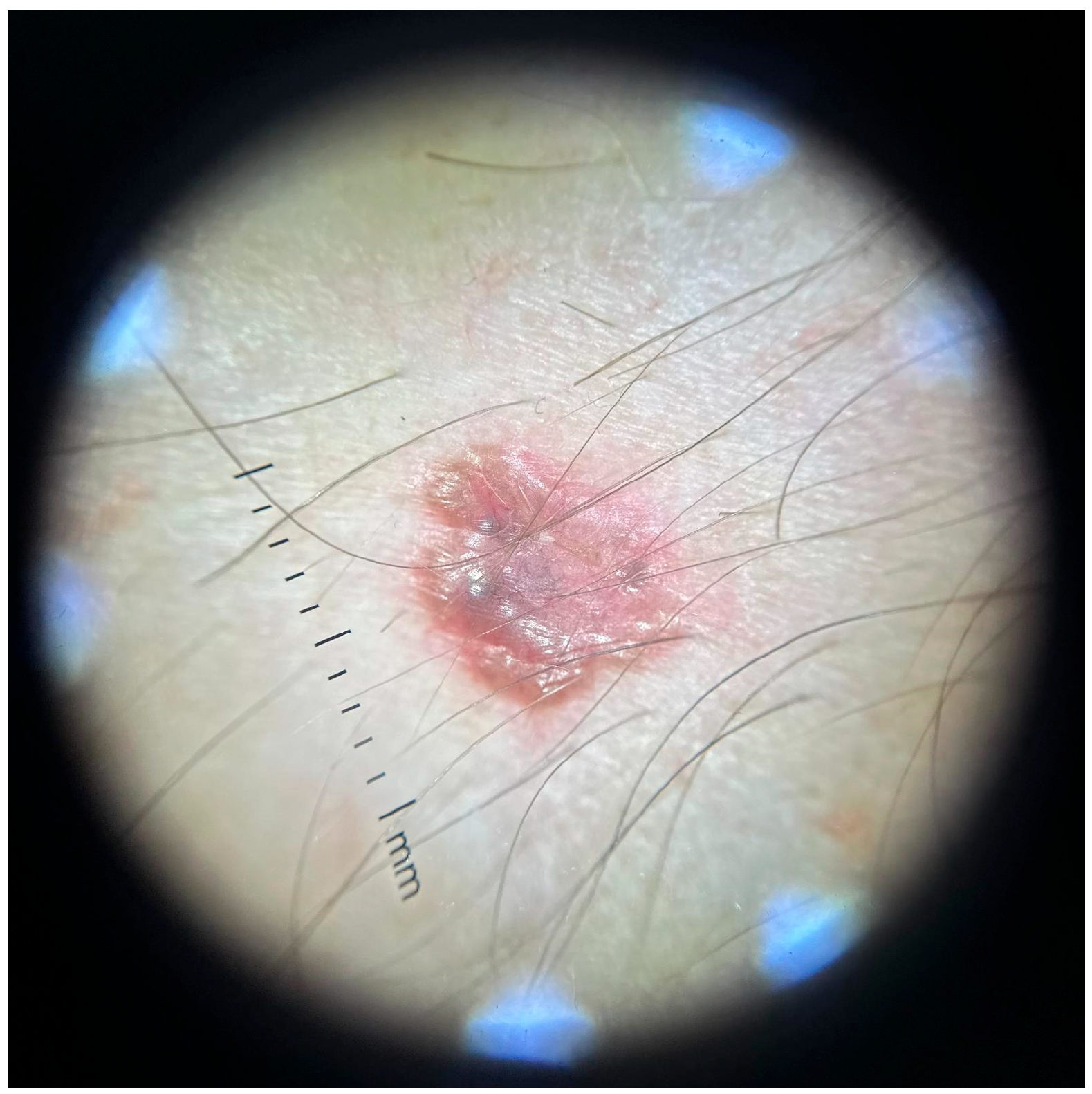

3.4. Dermoscopy and Diagnosis

3.5. Histopathology

3.6. Management and Follow-Up

4. Discussion and Literature Review

4.1. Risk of BCC After Childhood ALL and HSCT

4.2. Molecular Pathogenesis in HSCT Survivorship

Molecular Dermatology Perspective: Pathways, Biomarkers, and the “Field”

4.3. Dermoscopy in High-Risk Populations

4.4. Therapeutic Options

4.5. Dermatologic Surveillance in Survivorship

- Photoprotection and UV avoidance;

- Chemoprevention—randomized Phase III evidence supports oral nicotinamide (500 mg twice daily) in patients with prior NMSC to reduce new lesions during active treatment;

- Risk-adapted intervals for full-body dermoscopy;

- Consideration of topical field therapies (5-FU, imiquimod, daylight-PDT) for actinic field control;

4.5.1. Innovative Diagnostics: Digital Dermoscopy, AI, and Longitudinal Monitoring

4.5.2. Translational Therapeutics and Precision Prevention

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ALL | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| BCC | Basal Cell Carcinoma |

| BFM | Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster |

| BMT | Blood or Marrow Transplantation |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| GVHD | Graft-Versus-Host Disease |

| HHI | Hedgehog pathway Inhibitor |

| HSCT | Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation |

| NBCCS | Nevoid Basal Cell Carcinoma Syndrome |

| NMSC | Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer |

| ONTRAC | Oral Nicotinamide to Reduce Actinic Cancer |

| PD-1 | Programmed Death-1 |

| PDT | Photodynamic Therapy |

| PPC | Pediatric Palliative Care |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses—Scoping Reviews |

| PTCH1 | Protein patched homolog 1 |

| RT | Radiation Therapy (Radiotherapy) |

| SMNs | Secondary Malignant Neoplasms |

| SMO | Smoothened = a 7-transmembrane protein essential to the activation of Gli transcription factors (Gli) by hedgehog morphogens |

| TBI | Total Body Irradiation |

| TP53 | A gene that codes for the tumor protein p53 |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Roky, A.H.; Islam, M.M.; Ahasan, A.M.F.; Mostaq, M.S.; Mahmud, M.Z.; Amin, M.N.; Mahmud, M.A. Overview of skin cancer types and prevalence rates across continents. Cancer Pathog. Ther. 2024, 3, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhojwani, D.; Yang, J.J.; Pui, C.H. Biology of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 62, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza, S.D.; Sakamoto, K.M. Topics in pediatric leukemia—Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. MedGenMed 2005, 7, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, A.V.; Alecsa, M.S.; Popescu, R.; Starcea, M.I.; Mocanu, A.M.; Rusu, C.; Miron, I.C. Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Emerging Therapies—From Pathway to Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, S.P.; Mullighan, C.G. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1541–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Park, H.S.; Choi, E.J.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Kang, Y.A.; Jeon, M.; Woo, J.M.; et al. Effectiveness of prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy and risk factors of central nervous system relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2025, 66, 2249–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, S. Long-term health impacts of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation inform recommendations for follow-up. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2011, 4, 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R.E.; Rowlings, P.A.; Deeg, H.J.; Shriner, D.A.; Socié, G.; Travis, L.B.; Horowitz, M.M.; Witherspoon, R.P.; Hoover, R.N.; Sobocinski, K.A.; et al. Solid cancers after bone marrow transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavvari, S.; Makena, Y.; Sukhavasi, S.; Makena, M.R. Large Population Analysis of Secondary Cancers in Pediatric Leukemia Survivors. Children 2019, 6, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turcotte, L.M.; Whitton, J.A.; Friedman, D.L.; Hammond, S.; Armstrong, G.T.; Leisenring, W.; Robison, L.L.; Neglia, J.P. Risk of subsequent neoplasms during the fifth and sixth decades of life in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3568–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, J.L.; Tatum, K.L.; Devine, K.A.; Stephens, S.; Masterson, M.; Baig, A.; Hudson, S.V.; Coups, E.J. Skin cancer surveillance behaviors among childhood cancer survivors treated with radiation. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 554–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, G.T.; Chen, Y.; Yasui, Y.; Leisenring, W.; Gibson, T.M.; Mertens, A.C.; Stovall, M.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Bhatia, S.; Krull, K.R. Reduction in late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.C.; Eldomery, M.K.; Maciaszek, J.L.; Klco, J.M. Inherited Predispositions to Myeloid Neoplasms: Pathogenesis and Clinical Implications. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2025, 20, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Pilo, F.; Pettinau, M.; Piras, E.; Targhetta, C.; Rojas, R.; Deias, P.; Mulas, O.; Caocci, G. Impact of primary cancer history and molecular landscape in therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1563990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dores, G.M.; Linet, M.S.; Curtis, R.E.; Morton, L.M. Risks of therapy-related hematologic neoplasms beyond myelodysplastic syndromes and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 2023, 141, 951–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teepen, J.C.; Kok, J.L.; Kremer, L.C.; Tissing, W.J.E.; van den Heuvel-Eibrink, M.M.; Loonen, J.J.; Bresters, D.; van der Pal, H.J.; Versluys, B.; van Dulmen-den Broeder, E.; et al. Long-term risk of skin cancer among childhood cancer survivors: A DCOG-LATER cohort study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2019, 111, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, C.; Boull, C.; Lu, Z.; Liao, K.; Hasan, H.; Xu, L.; Sapkota, Y.; Howell, R.M.; Arnold, M.A.; Conces, M.R.; et al. Basal cell carcinoma risk prediction in survivors of childhood cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2025, 117, 2352–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apalla, Z.; Sotiriou, E.; Lallas, A.; Lazaridou, E.; Vakirlis, E.; Ioannides, D. Basal Cell Carcinoma in a Childhood Cancer Survivor: What Neurosurgeons Should Avoid. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2017, 3, 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wunderlich, K.C.; Orte Cano, C.; Suppa, M.; Gaide, O.; White, J.M.; Njimi, H.; Euromelanoma Working Group; Marmol, V.D. High-Frequency Basal Cell Carcinoma: Demographic, Clinical, and Histopathological Features in a Belgian Cohort. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFine, K.A.; Weinstock, M.A. Early-stage nonmelanoma skin cancer and radiation therapy in childhood. Arch. Dermatol. 2008, 144, 873–878. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, S.; Sklar, C. Second cancers in survivors of childhood cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Athar, M. Ionizing Radiation Exposure and Basal Cell Carcinoma Pathogenesis. Radiat. Res. 2016, 185, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, J.L.; Kopecky, K.J.; Mathes, R.W.; Leisenring, W.M.; Friedman, D.L.; Deeg, H.J. Basal cell skin cancer after total-body irradiation and hematopoietic cell transplantation. Radiat. Res. 2009, 171, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamoto, Y.; Lee, S.J. Late effects of blood and marrow transplantation. Haematologica 2017, 102, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. Therapy-related myelodysplasia and leukemia after childhood cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Cheong, S.; He, Y.; Lu, F. Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy for autoimmune-related fibrotic skin diseases—Systemic sclerosis and sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W.; Levine, J.E.; Ferrara, J.L. Pathogenesis and management of graft-versus-host disease. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2010, 30, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euvrard, S.; Kanitakis, J.; Claudy, A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, M.; Morimoto, T.; Maluccio, M.; Asano, T.; Morishita, Y.; Suthanthiran, M. Cyclosporine induces cancer progression by a cell-autonomous mechanism. Nature 1999, 397, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starace, M.; Rapparini, L.; Cedirian, S. Skin Malignancies Due to Anti-Cancer Therapies. Cancers 2024, 16, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ume, A.C.; Pugh, J.M.; Kemp, M.G.; Williams, C.R. Calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-associated skin cancers: New insights on exploring mechanisms by which CNIs downregulate DNA repair machinery. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2020, 36, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Colegio, O.R. Skin Cancers in Organ Transplant Recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 2509–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreher, M.A.; Noland, M.M.B.; Konda, S.; Longo, M.I.; Valdes-Rodriguez, R. Risk of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer with immunosuppressants, part I: Calcineurin inhibitors, thiopurines, IMDH inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, and corticosteroids. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.L.; Liu, Y.; Mitby, P.A.; Neglia, J.P.; Hammond, S.; Stovall, M.; Meadows, A.T.; Hutchinson, R.; Dreyer, Z.E.; Robison, L.L.; et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3733–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahayri, Z.N.; AlAhmad, M.M.; Ali, B.R. Long-Term Effects of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Chemotherapy: Can Recent Findings Inform Old Strategies? Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 710163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahnreich, S.; Schmidberger, H. Childhood Cancer: Occurrence, Treatment and Risk of Second Primary Malignancies. Cancers 2021, 13, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilcher, G.M.T.; Rivard, L.; Huang, J.T.; Wright, N.A.M.; Anderson, L.; Eissa, H.; Pelletier, W.; Ramachandran, S.; Schechter, T.; Shah, A.J.; et al. Immune function in childhood cancer survivors: A Children’s Oncology Group review. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2021, 5, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, S.M.; Dewees, T.; Shinohara, E.T.; Reddy, M.M.; Frangoul, H. Risk of subsequent malignancies in survivors of childhood leukemia. J. Cancer Surviv. 2013, 7, 544–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelidis, P.; Gavriilaki, E.; Tsakiris, D.A. Thrombotic complications after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and other cellular therapies. Thromb. Update 2024, 16, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broman, K.K.; Meng, Q.; Holmqvist, A.; Balas, N.; Richman, J.; Landier, W.; Hageman, L.; Ross, E.; Bosworth, A.; Te, H.S.; et al. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Cutaneous Malignant Neoplasms After Blood or Marrow Transplant. JAMA Dermatol. 2025, 161, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, T.; Hyun, G.; Dhaduk, R.; Conces, M.; Arnold, M.A.; Howell, R.M.; Henderson, T.O.; McDonald, A.; Robison, L.L.; Yasui, Y.; et al. Late subsequent leukemia after childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). Cancer Med. 2024, 13, e70086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızılocak, H.; Okcu, F. Late Effects of Therapy in Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Survivors. Turk. J. Haematol. 2019, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M.M.; Link, M.P.; Simone, J.V. Milestones in the curability of pediatric cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2391–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, L.L.; Hudson, M.M. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: Life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, E.J.; Anderson, L.; Baker, K.S.; Bhatia, S.; Guilcher, G.M.; Huang, J.T.; Pelletier, W.; Perkins, J.L.; Rivard, L.S.; Schechter, T. Late Effects Surveillance Recommendations among Survivors of Childhood Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: A Children’s Oncology Group Report. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016, 22, 782–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gruijl, F.R.; Tensen, C.P. Pathogenesis of Skin Carcinomas and a Stem Cell as Focal Origin. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Silva, R.; Melo, T.M.V.D.P.E.; Inga, A.; Saraiva, L. P53 and the Ultraviolet Radiation-Induced Skin Response: Finding the Light in the Darkness of Triggered Carcinogenesis. Cancers 2024, 16, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aszterbaum, M.; Epstein, J.; Oro, A.; Douglas, V.; LeBoit, P.E.; Scott, M.P.; Epstein, E.H., Jr. Ultraviolet and ionizing radiation enhance the growth of BCCs and trichoblastomas in patched heterozygous knockout mice. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Fernandez, K.; Fadadu, R.P.; Reddy, R.; Kim, M.O.; Tan, J.; Wei, M.L. Skin Cancer Diagnosis by Lesion, Physician, and Examination Type: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2025, 161, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, C.M.; Sivesind, T.E.; Dellavalle, R.P. From the Cochrane Library: Visual Inspection and Dermoscopy, Alone or in Combination, for Diagnosing Keratinocyte Skin Cancers in Adults. JMIR Dermatol. 2024, 7, e41657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinnes, J.; Deeks, J.J.; Chuchu, N.; Matin, R.N.; Wong, K.Y.; Aldridge, R.B.; Durack, A.; Gulati, A.; Chan, S.A.; Johnston, L.; et al. Visual inspection and dermoscopy, alone or in combination, for diagnosing keratinocyte skin cancers in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 12, CD011901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, H.T.; Swanson, D.L.; Sartori-Valinotti, J.C.; O’Laughlin, D.J.; Young, P.A.; Merry, S.P.; Nelson, K.; Fischer, K.; Weatherly, R.M.; Boswell, C.L. Impact of Dermoscopy Training on Diagnostic Accuracy, and Its Association With Biopsy and Referral Patterns Among Primary Care Providers: A Retrospective and Prospective Educational Intervention Study. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2024, 15, 21501319241296625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K. The Accuracy of Skin Cancer Detection Rates with the Implementation of Dermoscopy Among Dermatology Clinicians: A Scoping Review. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2024, 17, S18–S27. [Google Scholar]

- Hizanu Dumitrache, M.; Duceac Covrig, M.; Mîndru, D.E.; Plesea Condratovici, A.; Mitrea, G.; Elkan, E.M.; Curici, A.; Gafton, B.; Duceac, L.D. The Need for Pediatric Palliative Care in Romania: A Retrospective Study (2022–2023) Based on Quantitative Research and Analysis of Secondary Statistical Data. Medicina 2025, 61, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohan, T.Z.; Mandel, J.; Banner, L.; Zachian, R.; Yang, H.; Lee, E.; O’Donnell-Cappelli, M.; Bhatti, S.; Zhan, T.; Lee, J.B.; et al. The risk of developing second primary malignancies in cutaneous melanoma survivors. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2025, 92, 914–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, M.; Telehuz, A.; Voinescu, D.C.; Sapira, V.; Trifan, A.; Elkan, E.M.; Fătu, A.; Creangă, V.Z.; Polinschi, M.; Stoleriu, G.; et al. NK/T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Case report and review of the literature. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wa, Q.; Chen, Z. Extracutaneous second primary cancer risk in nonmelanoma skin cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2025, 212, 104769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halmágyi, S.-R.; Ungureanu, L.; Trufin, I.-I.; Apostu, A.P.; Șenilă, S.C. Melanoma as Subsequent Primary Malignancy in Hematologic Cancer Survivors—A Literature Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boull, C.; Chen, Y.; Im, C.; Geller, A.; Sapkota, Y.; Bates, J.E.; Howell, R.; Arnold, M.A.; Conces, M.; Constine, L.S.; et al. Keratinocyte carcinomas in survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 91, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupu, M.; Caruntu, C.; Popa, M.I.; Voiculescu, V.M.; Zurac, S.; Boda, D. Vascular patterns in basal cell carcinoma: Dermoscopic, confocal and histopathological perspectives. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 4112–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peris, K.; Fargnoli, M.C.; Kaufmann, R.; Arenberger, P.; Bastholt, L.; Seguin, N.B.; Bataille, V.; Brochez, L.; Del Marmol, V.; Dummer, R.; et al. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline for diagnosis and treatment of basal cell carcinoma—Update 2023. Eur. J. Cancer 2023, 192, 113254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtowicz, I.; Żychowska, M. Dermoscopy of Basal Cell Carcinoma Part 1: Dermoscopic Findings and Diagnostic Accuracy—A Systematic Literature Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsness, S.L.; Freites-Martinez, A.; Marchetti, M.A.; Navarrete-Dechent, C.; Lacouture, M.E.; Tonorezos, E.S. Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer in Childhood and Young Adult Cancer Survivors Previously Treated with Radiotherapy. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambhia, P.H.; Conic, R.Z.; Atanaskova-Mesinkovska, N.; Piliang, M.; Bergfeld, W.F. Role of graft-versus-host disease in the development of secondary skin cancers in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: A meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 79, 378–380.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsohn, D.A.; Vogelsang, G.B. Acute graft versus host disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2007, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, K.R.; Luznik, L.; Sarantopoulos, S.; Hakim, F.T.; Jagasia, M.; Fowler, D.H.; van den Brink, M.R.M.; Hansen, J.A.; Parkman, R.; Miklos, D.B.; et al. The Biology of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: A Task Force Report from the NIH Consensus Development Project. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017, 23, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gail, L.M.; Schell, K.J.; Łacina, P.; Strobl, J.; Bolton, S.J.; Steinbakk Ulriksen, E.; Bogunia-Kubik, K.; Greinix, H.; Crossland, R.E.; Inngjerdingen, M.; et al. Complex interactions of cellular players in chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1199422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granata, S.; Tessari, G.; Stallone, G.; Zaza, G. Skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients: Still an open problem. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1189680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zavattaro, E.; Fava, P.; Veronese, F.; Cavaliere, G.; Ferrante, D.; Cantaluppi, V.; Ranghino, A.; Biancone, L.; Fierro, M.T.; Savoia, P. Identification of Risk Factors for Multiple Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers in Italian Kidney Transplant Recipients. Medicina 2019, 55, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santangelo, M.L.; Criscitiello, C.; Renda, A.; Federico, S.; Curigliano, G.; Dodaro, C.; Scotti, A.; Tammaro, V.; Calogero, A.; Riccio, E.; et al. Immunosuppression and Multiple Primary Malignancies in Kidney-Transplanted Patients: A Single-Institute Study. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 183523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.J.; Eissa, H.M.; Bhatt, N.S.; Huang, S.; Ehrhardt, M.J.; Bhakta, N.; Ness, K.K.; Krull, K.R.; Srivastava, D.K.; Robison, L.L.; et al. Patient-reported outcomes in survivors of childhood hematologic malignancies with hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Blood 2020, 135, 1847–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amonoo, H.L.; Markovitz, N.H.; Johnson, P.C.; Kwok, A.; Dale, C.; Deary, E.C.; Daskalakis, E.; Choe, J.J.; Yamin, N.; Gothoskar, M.; et al. Delirium and Healthcare Utilization in Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transplant. Cell Ther. 2023, 29, 334.e1–334.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvelier, G.D.E.; Schoettler, M.; Buxbaum, N.P.; Pinal-Fernandez, I.; Schmalzing, M.; Distler, J.H.W.; Penack, O.; Santomasso, B.D.; Zeiser, R.; Angstwurm, K.; et al. Atypical Features of Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease: 2020 NIH Consensus Project Task Force Report. Transplant. Cell Ther. 2022, 28, 426–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesch-Furlanetto, T.; Gabriel, M.; Zajac-Spychala, O.; Cattoni, A.; Hoeben, B.A.W.; Balduzzi, A. Late Effects After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in ALL, Long-Term Follow-Up and Transition. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 773895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Kim, S.; Wasko, C. Dermatological guide for primary care physicians: Full body skin checks, skin cancer detection, and patient education on self-skin checks and sun protection. In Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2024; Volume 37, pp. 647–654. [Google Scholar]

- Jurakić Tončić, R.; Vasari, L.; Štulhofer Buzina, D.; Ledić Drvar, D.; Petković, M.; Čeović, R. The Role of Digital Dermoscopy and Follow-Up in the Detection of Amelanotic/Hypomelanotic Melanoma in a Group of High-Risk Patients—Is It Useful? Life 2024, 14, 1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugan, M.M.; Shannon, A.B.; DePalo, D.K.; Tsai, K.Y.; Farma, J.M.; Gonzalez, R.J.; Zager, J.S. Current management of nonmelanoma skin cancers. Curr. Probl. Surg. 2025, 62, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallas, A.; Argenziano, G.; Zendri, E.; Moscarella, E.; Longo, C.; Grenzi, L.; Pellacani, G.; Zalaudek, I. Update on non-melanoma skin cancer and the value of dermoscopy in its diagnosis and treatment monitoring. Expert Rev. Anticancer. Ther. 2013, 13, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurley, A.R.; Totty, J.P.; Pinder, R.M. Dermoscopy as an adjunct to surgical excision of nonmelanoma skin lesions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wolner, Z.J.; Yélamos, O.; Liopyris, K.; Rogers, T.; Marchetti, M.A.; Marghoob, A.A. Enhancing Skin Cancer Diagnosis with Dermoscopy. Dermatol. Clin. 2017, 35, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefrançois, P.; Ghezelbash, S.; Nallanathan, B.; Cohn, H.; Xie, P.; Litvinov, I.V.; Billick, R.C.; Blouin, M.M.; Khanna, M.; Fortier-Riberdy, G.; et al. 63205 The Transcriptional Landscape Analysis of High-Risk Aggressive Basal Cell Carcinoma Identifies Subtype-Specific Biomarkers and Cancer Promotion Pathways. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2025, 93, AB326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukes, M.W.; Meade, T.J. Modulation of Hedgehog Signaling for the Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma and the Development of Preclinical Models. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Dai, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Lin, Y.; Somani, A.K.; Xie, J.; Han, J. Distinct transcriptomic landscapes of cutaneous basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas. Genes Dis. 2019, 8, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, P.; Kłosińska, M.; Forma, A.; Pelc, Z.; Gęca, K.; Skórzewska, M. Novel Approaches in Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers—A Focus on Hedgehog Pathway in Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC). Cells 2022, 11, 3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambini, D.; Passoni, E.; Nazzaro, G.; Beltramini, G.; Tomasello, G.; Ghidini, M.; Kuhn, E.; Garrone, O. Basal Cell Carcinoma and Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitors: Focus on Immune Response. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 893063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, H.C.; Rossouw, T.M.; Anderson, R.; Anderson, L.; van Tonder, D.; Smit, T.; Rapoport, B.L. Immunopathogenesis and Therapeutic Implications in Basal Cell Carcinoma: Current Concepts and Future Directions. Medicina 2025, 61, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Sulthana, S.; Strauss, J.; Puri, A.; Priyanka Bandi, S.; Singh, S. Reconnoitring signaling pathways and exploiting innovative approaches tailoring multifaceted therapies for skin cancer. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 665, 124719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibanez, J.F.; Villar, V.H.; Echeverria, C. Current and Future Cancer Chemoprevention Strategies. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, Q.; Tao, X.; Xia, J.; Wu, T.; Cheng, B.; Wang, J. Retinoids in cancer chemoprevention and therapy: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1065320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosti, G.; Pepe, F.; Gnagnarella, P.; Silvestri, F.; Gaeta, A.; Queirolo, P.; Gandini, S. The Role of Nicotinamide as Chemo-Preventive Agent in NMSCs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tow, R.; Hanoun, S.; Andresen, B.; Shahid, A.; Wang, J.; Kelly, K.M.; Meyskens, F.L., Jr.; Huang, Y. Recent Advances in Clinical Research for Skin Cancer Chemoprevention. Cancers 2023, 15, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger-Heidrich, K.; Wolters, F.; Frick, M.; Halbsguth, T.; Müller, T.; Woopen, H.; Tausche, K.; Richter, D.; Gebauer, J. Long-term surveillance recommendations for young adult cancer survivors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2025, 139, 102992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, J.E.; Hoffmeister, P.A.; Storer, B.E.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Storb, R.F.; Syrjala, K.L. The quality of life of adult survivors of childhood hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010, 45, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangoul, H.; Najjar, J.; Simmons, J.; Domm, J. Long-term follow-up and management guidelines in pediatric patients after allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Semin. Hematol. 2012, 49, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, E.; Kinsey, S.; Bonaventure, A.; Johnston, T.; Simpson, J.; Howell, D.; Smith, A.; Roman, E. Excess morbidity and mortality among survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: 25 years of follow-up from the UKCCS. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deinlein, T.; Richtig, G.; Schwab, C.; Scarfi, F.; Arzberger, E.; Wolf, I.; Hofmann-Wellenhof, R.; Zalaudek, I. The use of dermatoscopy in diagnosis and therapy of nonmelanocytic skin cancer. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2016, 14, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, N.; Bucholc, J.; Ng, L.; Chai, K.; Livingstone, A.; Murphy, A.; Gordon, L.G. Protocol for a systematic review of reviews on training primary care providers in dermoscopy to detect skin cancers. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e079052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballotti, R.; Healy, E.; Bertolotto, C. Nicotinamide as a chemopreventive therapy of skin cancers. Too much of good thing? Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2019, 32, 601–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahradyan, A.; Howell, A.C.; Wolfswinkel, E.M.; Tsuha, M.; Sheth, P.; Wong, A.K. Updates on the Management of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancer (NMSC). Healthcare 2017, 5, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, P.; Ascierto, P.A.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Dreno, B.; Dummer, R.; Hauschild, A.; Mohr, P.; Kaufmann, R.; Pellacani, G.; Puig, S.; et al. Long-term strategies for management of advanced basal cell carcinoma with hedgehog inhibitors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2023, 189, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.C.; Martin, A.J.; Choy, B.; Fernández-Peñas, P.; Dalziell, R.A.; McKenzie, C.A.; Scolyer, R.A.; Dhillon, H.M.; Vardy, J.L.; Kricker, A.; et al. A Phase 3 Randomized Trial of Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1618–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breglio, K.F.; Knox, K.M.; Hwang, J.; Weiss, R.; Maas, K.; Zhang, S.; Yao, L.; Madden, C.; Xu, Y.; Hartman, R.I.; et al. Nicotinamide for Skin Cancer Chemoprevention. JAMA Dermatol. 2025, 161, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, B.; Gómez-Cayupán, J.; Aranis, I.; García Tapia, E.; Coghlan, C.; Ulloa, M.J.; Gelerstein Claro, S.; Urbina, K.; Espinoza, G.; De Grazia, J.; et al. Oxidative Stress-Mediated DNA Damage Induced by Ionizing Radiation in Modern Computed Tomography: Evidence for Antioxidant-Based Radioprotective Strategies. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignard, J.; Mirey, G.; Salles, B. Ionizing-radiation induced DNA double-strand breaks: A direct and indirect lighting up. Radiother. Oncol. 2013, 108, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavragani, I.V.; Nikitaki, Z.; Kalospyros, S.A.; Georgakilas, A.G. Ionizing Radiation and Complex DNA Damage: From Prediction to Detection Challenges and Biological Significance. Cancers 2019, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Chen, X.; Wu, H.; Ning, D.; Cao, X.; Wan, C. Prediction of Diagnostic Gene Biomarkers Associated with Immune Infiltration for Basal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 2657–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddadin, L.; Sun, X. Stem Cells in Cancer: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Cells 2025, 14, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, X.; Wang, T.; Guo, S.; Dang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; He, H.; Li, L.; Yuan, H.; He, T.; et al. Case report: A novel PTCH1 frameshift mutation leading to nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1327505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kim, B.; Park, J.; Park, S.; Yoo, G.; Yum, S.; Kang, W.; Lee, J.M.; Youn, H.; Youn, B. Cancer stem cells: Landscape, challenges and emerging therapeutic innovations. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borroni, R.G.; Panasiti, V.; Valenti, M.; Gargiulo, L.; Perrone, G.; Dall’Alba, R.; Fava, C.; Sacrini, F.; Mancini, L.L.; Manara, S.A.; et al. Long-Term Sequential Digital Dermoscopy of Low-Risk Patients May Not Improve Early Diagnosis of Melanoma Compared to Periodical Handheld Dermoscopy. Cancers 2023, 15, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, D.L. Nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2017, 58, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, D.L. Photoprotective effects of nicotinamide. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2010, 9, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDQ Cancer Genetics Editorial Board. Genetics of Skin Cancer (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. In PDQ Cancer Information Summaries; National Cancer Institute (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Krakowski, A.C.; Hafeez, F.; Westheim, A.; Pan, E.Y.; Wilson, M. Advanced basal cell carcinoma: What dermatologists need to know about diagnosis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 86, S1–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wladis, E.J.; Aakalu, V.K.; Vagefi, M.R.; Tao, J.P.; McCulley, T.J.; Freitag, S.K.; Foster, J.A.; Kim, S.J. Oral Hedgehog Inhibitor, Vismodegib, for Locally Advanced Periorbital and Orbital Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dummer, R.; Ascierto, P.A.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Dréno, B.; Garbe, C.; Gutzmer, R.; Hauschild, A.; Krattinger, R.; Lear, J.T.; Malvehy, J.; et al. Sonidegib and vismodegib in the treatment of patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma: A joint expert opinion. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 1944–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnia Wijaya, J.; Djawad, K.; Wahab, S.; Nurdin, A.; Irawan Anwar, A. Vismodegib and Sonidegib in Locally Advanced and Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma: Update on Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitors. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2022, 113, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Armbruster, H.; Pardo, G.; Archambeau, B.; Kim, N.H.; Jeter, J.; Wu, R.; Kendra, K.; Contreras, C.M.; Spaccarelli, N.; et al. Hedgehog pathway inhibitors for locally advanced and metastatic basal cell carcinoma: A real-world single-center retrospective review. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, A.M.; Burshtein, J.; Christopher, M.; Cockerell, C.; Correa, L.; Cotter, D.; Ellis, D.L.; Farberg, A.S.; Grant-Kels, J.M.; Greiling, T.M.; et al. Clinical Utility of a Digital Dermoscopy Image-Based Artificial Intelligence Device in the Diagnosis and Management of Skin Cancer by Dermatologists. Cancers 2024, 16, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawani, H.T.; Senan, E.M.; Asiri, Y.; Abunadi, I.; Mashraqi, A.M.; Alshari, E.A. Enhanced early skin cancer detection through fusion of vision transformer and CNN features using hybrid attention of EViT-Dens169. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farberg, A.S.; Portela, D.; Sharma, D.; Kheterpal, M. Evaluation of the Tolerability of Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitors in the Treatment of Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Narrative Review of Treatment Strategies. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2024, 25, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.; Johnson, R.P.; Senft, S.C.; Pan, E.Y.; Krakowski, A.C. Advanced basal cell carcinoma: What dermatologists need to know about treatment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 86, S14–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafeez, F.; Wilson, M.; Senft, S.C.; Johnson, R.P.; Westheim, A.; Abidi, N.; Krakowski, A.C. Advanced basal cell carcinoma: What dermatologists need to know about treatment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagcchi, S. Nicotinamide yields impressive results in skin cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, F.; Ciccarese, G.; Parodi, A. Nicotinamide for Skin-Cancer Chemoprevention. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 789–790. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, S.V.; Jamison, A.; Malhotra, R. Oral nicotinamide for non-melanoma skin cancers: A review. Eye 2023, 37, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silk, A.W.; Barker, C.A.; Bhatia, S.; Bollin, K.B.; Chandra, S.; Eroglu, Z.; Gastman, B.R.; Kendra, K.L.; Kluger, H.; Lipson, E.J.; et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of nonmelanoma skin cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lamberti, G.; Di Federico, A.; Alessi, J.; Ferrara, R.; Sholl, M.L.; Awad, M.M.; Vokes, N.; Ricciuti, B. Tumor mutational burden for the prediction of PD-(L)1 blockade efficacy in cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessinioti, C.; Stratigos, A.J. Immunotherapy and Its Timing in Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma Treatment. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2023, 13, e2023252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratigos, A.J.; Sekulic, A.; Peris, K.; Bechter, O.; Prey, S.; Lewis, K.D.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Chang, A.L.S.; Dalle, S.; Fernández Orland, A.; et al. Phase 2 open-label, multi-center, single-arm study of cemiplimab in patients with locally advanced basal cell carcinoma after hedgehog inhibitor therapy: Extended follow-up. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakirtzi, K.; Papadimitriou, I.; Vakirlis, E.; Lallas, A.; Sotiriou, E. Photodynamic Therapy for Field Cancerization in the Skin: Where Do We Stand? Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2023, 13, e2023291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Liu, L.; Yang, W.; Wang, D. Surgery combined with photodynamic therapy versus surgery alone for the treatment of non-melanoma skin cancer and actinic keratosis: A retrospective cohort study. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 35, e15652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algorri, J.F.; López-Higuera, J.M.; Rodríguez-Cobo, L.; Cobo, A. Advanced Light Source Technologies for Photodynamic Therapy of Skin Cancer Lesions. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotiriou, E.; Kiritsi, D.; Chaitidis, N.; Arabatzis, M.; Lallas, A.; Vakirlis, E. Daylight Photodynamic Therapy for Actinic Keratosis and Field Cancerization: A Narrative Review. Cancers 2025, 17, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year/Period | Age | Clinical Event | Diagnostic Procedures | Histopathologic Findings | Therapeutic Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Childhood | Treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Hematologic evaluation; imaging | — | Allogeneic HSCT following conditioning with total body irradiation (12 Gy) and cyclophosphamide |

| 2007–2008 | Childhood | Acute graft-versus-host disease | Clinical assessment (skin, gastrointestinal tract) | — | Systemic immunosuppression (cyclosporine, corticosteroids); aGvHD graded according to modified Glucksberg criteria (Grade II) |

| 2014 | Young adult | Long-term remission | Routine hematologic follow-up | — | Discontinuation of immunosuppressive therapy |

| 2022 | 34 | First cutaneous lesion detected (left lumbar region) | Full-body clinical examination; dermoscopy; skin biopsy | Basal cell carcinoma, nodular subtype | Complete surgical excision |

| 2022–2023 | 34–35 | Sequential development of multiple skin lesions (n = 10) | Repeated full-body examinations; serial dermoscopic assessments | Multiple basal cell carcinomas (nodular and superficial subtypes) | Staged surgical excisions; curettage where appropriate |

| 2023 | 35 | Multidisciplinary management | Dermatologic and plastic surgery evaluation | Confirmatory histopathology of excised lesions | Surgical management; systemic therapies (Hedgehog pathway inhibitors) not indicated |

| Ongoing | — | Survivorship follow-up | Regular dermatologic surveillance; dermoscopy-assisted monitoring | — | Lifelong follow-up; patient education; self-skin examination; hematologic survivorship care |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Porumb-Andrese, E.; Stoleriu, G.; Huțanu, A.E.; Mârţu, C.; Toader, M.-P.; Porumb, V.; Colac-Boțoc, C.; Lupu, A.; Rusu-Zota, G.; Anton, E.; et al. Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas in a Long-Term Survivor of Childhood ALL and HSCT—A Call for Dermatologic Vigilance. Life 2026, 16, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010055

Porumb-Andrese E, Stoleriu G, Huțanu AE, Mârţu C, Toader M-P, Porumb V, Colac-Boțoc C, Lupu A, Rusu-Zota G, Anton E, et al. Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas in a Long-Term Survivor of Childhood ALL and HSCT—A Call for Dermatologic Vigilance. Life. 2026; 16(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010055

Chicago/Turabian StylePorumb-Andrese, Elena, Gabriela Stoleriu, Antonia Elena Huțanu, Cristian Mârţu, Mihaela-Paula Toader, Vlad Porumb, Cristina Colac-Boțoc, Ancuța Lupu, Gabriela Rusu-Zota, Emil Anton, and et al. 2026. "Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas in a Long-Term Survivor of Childhood ALL and HSCT—A Call for Dermatologic Vigilance" Life 16, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010055

APA StylePorumb-Andrese, E., Stoleriu, G., Huțanu, A. E., Mârţu, C., Toader, M.-P., Porumb, V., Colac-Boțoc, C., Lupu, A., Rusu-Zota, G., Anton, E., & Brănișteanu, D. E. (2026). Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas in a Long-Term Survivor of Childhood ALL and HSCT—A Call for Dermatologic Vigilance. Life, 16(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010055