Sex-Specific Patterns of Cortisol Fluctuation, Stress, and Academic Success in Quarantined Foreign Medical Students During the COVID-19 Lockdown

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Salivary Cortisol Is a Non-Invasive Stress Biomarker

1.2. COVID-19 Pandemic Was Serious Stressor

1.3. Quarantine Measures for Foreign Medical Students in Ukraine

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Sampling of Salivary Cortisol

Mathematical Saliva Cortisol-Based Clustering of Participants

2.4. Instruments for Assessing Perceived Stress and Health Concerns

PSS-10 Scale Validation and Factor Extraction

2.5. Students’ Academic Success

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

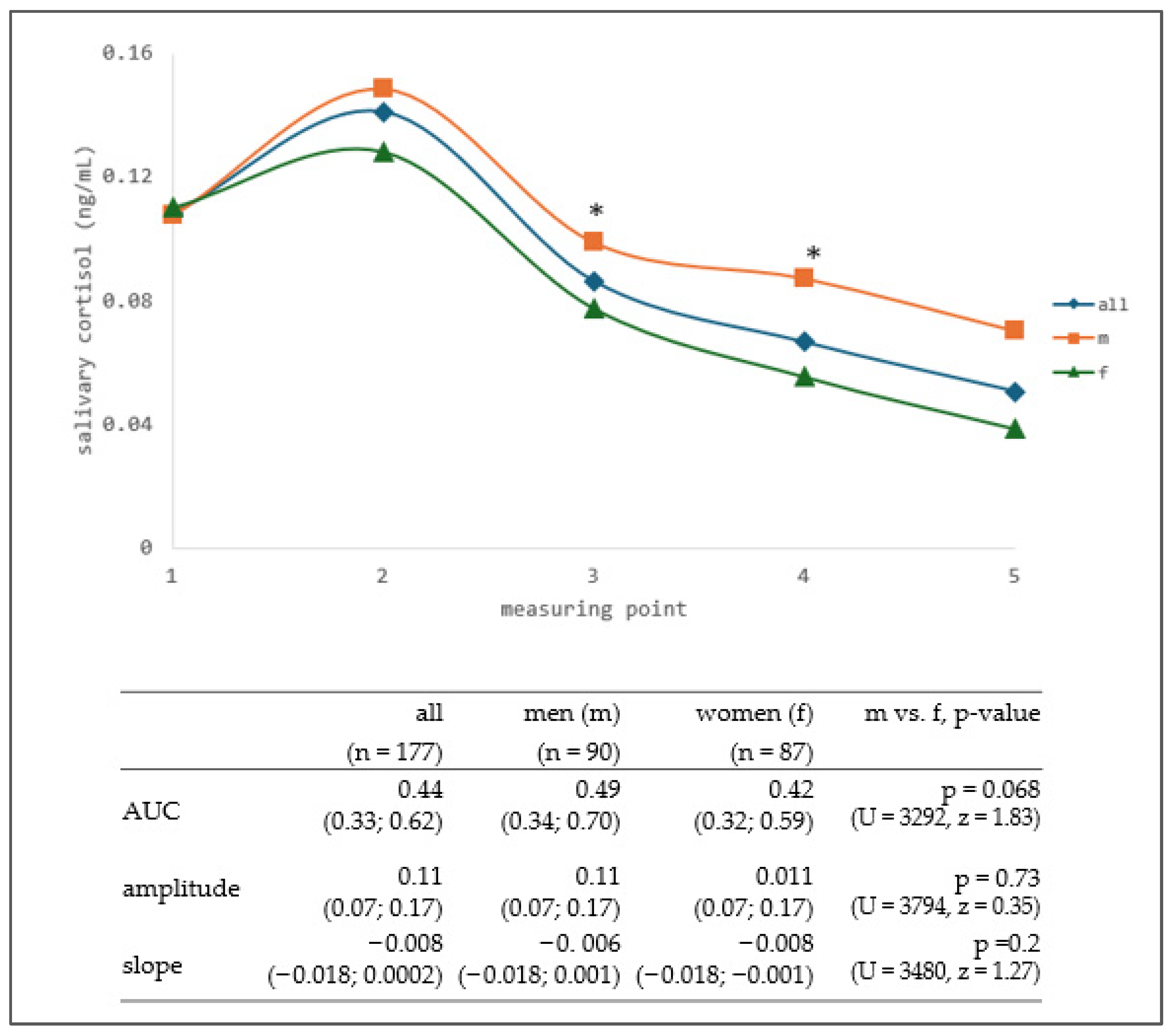

3.1. Salivary Cortisol

Mathematical Clustering of Participants According to the Salivary Cortisol Daily Fluctuation

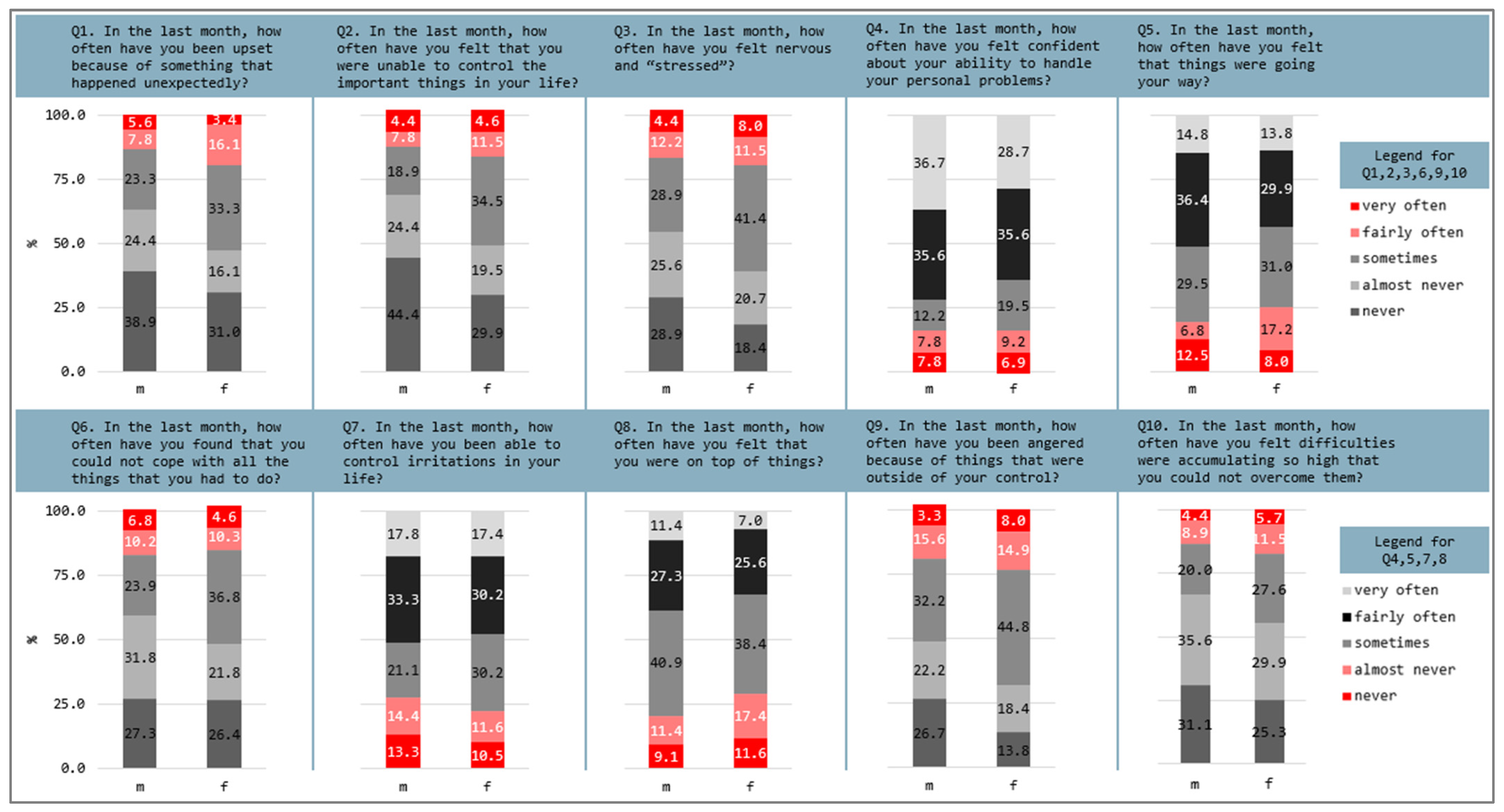

3.2. Perceived Stress and Health Concerns

3.3. Academic Success 2018/2019–2020/2021

4. Discussion

4.1. Sex-Specific Patterns and Mathematical Clustering of Salivary Cortisol

4.2. Perceived Stress and Somatic Symptoms

4.3. Sex-Specific Correlation Between Physiological and Psychological Stress Markers

4.4. Academic Success Trends Under Lockdown-Induced Stress

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | area under the curve |

| COVID-19 | SARS-CoV-2 pandemic |

| HPA | hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis |

| KFF | The Kaiser Family Foundation |

| LSE | lack of self-efficacy |

| MAPart | the most appropriate number of clusters |

| PH | perceived helplessness |

| PSS-10 | Perceived Stress Scale-10 |

| PTSD | post-traumatic stress disorder |

| TNMU | I. Horbachevsky Ternopil National Medical University, Ternopil, Ukraine |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

Appendix A

| Group | 2018/2019 | n | 2019/2020 | n | 2020/2021 | n | p-Value § |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | * 4.0 (3.7; 4.0) | 45 | 4.0 (3.8; 4.0) | 90 | * 4.0 (4.0; 4.1) | 90 | * p < 0.001 |

| M-π1 | † 4.0 (3.5; 4.0) | 23 | * 4.0 (3.8; 4.2) | 46 | *† 4.0 (4.0; 4.1) | 46 | * p = 0.033; † p = 0.008 |

| M-π2 | 3.9 (3.7; 4.1) | 6 | 4.0 (3.9; 4.0) | 13 | 4.0 (4.0; 4.1) | 13 | |

| M-π3 | 3.8 (3.1; 4.0) | 7 | 4.0 (3.7; 4.2) | 17 | 4.0 (4.0; 4.1) | 17 | |

| M-π4 | 4.0 (3.7; 4.2) | 6 | 3.8 (3.8; 4.0) | 10 | 4.0 (3.9; 4.2) | 10 | |

| M-π5 | 4.0 (3.8; 4.0) | 3 | 4.1 (4.0; 4.4) | 4 | 4.2 (4.0; 4.3) | 4 | |

| F | †‡ 3.8 (3.7; 4.0) | 44 | *† 4.0 (3.9; 4.2) | 86 | *‡ 4.0 (4.0; 4.2) | 86 | * p = 0.025; † p = 0.022; ‡ p < 0.001 |

| F-π1 | †‡ 3.8 (3.6; 4.0) | 33 | *† 4.0 (3.8; 4.2) | 58 | *‡ 4.0 (4.0; 4.2) | 58 | * p = 0.004; † p = 0.009; ‡ p < 0.001 |

| F-π2 | 4.2 (4.0; 4.4) | 2 | 4.0 (4.0; 4.3) | 5 | 4.0 (4.0; 4.3) | 5 | |

| F-π3 | 4.0 (4.0; 4.2) | 5 | 4.1 (4.0; 4.2) | 14 | 4.0 (4.0; 4.1) | 14 | |

| F-π4 | - | 0 | 4.0 (3.8; 4.2) | 2 | 4.0 (4.0; 4.0) | 2 | |

| F-π5 | 4.0 (4.0; 4.0) | 4 | 3.9 (3.6; 4.2) | 7 | 4.0 (3.9; 4.4) | 7 |

References

- Smith, S.M.; Vale, W.W. The Role of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in Neuroendocrine Responses to Stress. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 8, 383–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamgang, V.W.; Murkwe, M.; Wankeu-Nya, M.; Kamgang, V.W.; Murkwe, M.; Wankeu-Nya, M. Biological Effects of Cortisol. In Cortisol—Between Physiology and Pathology; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-0-85466-091-9. [Google Scholar]

- Paragliola, R.M.; Corsello, A.; Troiani, E.; Locantore, P.; Papi, G.; Donnini, G.; Pontecorvi, A.; Corsello, S.M.; Carrozza, C. Cortisol Circadian Rhythm and Jet-Lag Syndrome: Evaluation of Salivary Cortisol Rhythm in a Group of Eastward Travelers. Endocrine 2021, 73, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzinga, B.M.; Schmahl, C.G.; Vermetten, E.; van Dyck, R.; Bremner, J.D. Higher Cortisol Levels Following Exposure to Traumatic Reminders in Abuse-Related PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 28, 1656–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.H.; Walton, J.C.; DeVries, A.C.; Nelson, R.J. Circadian Rhythm Disruption and Mental Health. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, M. Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders. Continuum 2017, 23, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leeuw, M.; Verhoeve, S.I.; van der Wee, N.J.A.; van Hemert, A.M.; Vreugdenhil, E.; Coomans, C.P. The Role of the Circadian System in the Etiology of Depression. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 153, 105383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.; Debono, M. Replication of Cortisol Circadian Rhythm: New Advances in Hydrocortisone Replacement Therapy. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 1, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giubilei, F.; Patacchioli, F.R.; Antonini, G.; Monti, M.S.; Tisei, P.; Bastianello, S.; Monnazzi, P.; Angelucci, L. Altered Circadian Cortisol Secretion in Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical and Neuroradiological Aspects. J. Neurosci. Res. 2001, 66, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamak, M.; Tükenmez, H.; Sertbaş, M.; Tükenmez, M.A.; Ahbab, S.; Ataoğlu, H.E. Cortisol as a Predictor of Early Mortality in Heart Failure. South. Clin. Istanb. EURASIA 2020, 31, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisan, M.-P. Sexual Dimorphism in Glucocorticoid Stress Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reschke-Hernández, A.E.; Okerstrom, K.L.; Edwards, A.B.; Tranel, D. Sex and Stress: Men and Women Show Different Cortisol Responses to Psychological Stress Induced by the Trier Social Stress Test and the Iowa Singing Social Stress Test. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 95, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Kogler, L.; Derntl, B. Sex Differences in Cortisol Levels in Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2024, 72, 101118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, H.; Challet, E.; Ott, V.; Arvat, E.; de Kloet, E.R.; Dijk, D.-J.; Lightman, S.; Vgontzas, A.; Van Cauter, E. The Functional and Clinical Significance of the 24-Hour Rhythm of Circulating Glucocorticoids. Endocr. Rev. 2017, 38, 3–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoye, D.Q.; Boardman, J.P.; Osmond, C.; Sullivan, G.; Lamb, G.; Black, G.S.; Homer, N.Z.M.; Nelson, N.; Theodorsson, E.; Mörelius, E.; et al. Saliva Cortisol Diurnal Variation and Stress Responses in Term and Preterm Infants. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2022, 107, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellhammer, D.H.; Wüst, S.; Kudielka, B.M. Salivary Cortisol as a Biomarker in Stress Research. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2009, 34, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozma, S.; Dima-Cozma, L.C.; Ghiciuc, C.M.; Pasquali, V.; Saponaro, A.; Patacchioli, F.R. Salivary Cortisol and α-Amylase: Subclinical Indicators of Stress as Cardiometabolic Risk. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Medicas Biol. 2017, 50, e5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vari, S.G. COVID-19 Infection: Disease Mechanism, Vascular Dysfunction, Immune Responses, Markers, Multiorgan Failure, Treatments, and Vaccination. Ukr. Biochem. J. 2020, 92, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Dalamitros, A.A.; Beltran-Velasco, A.I.; Mielgo-Ayuso, J.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Social and Psychophysiological Consequences of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Extensive Literature Review. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 580225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worldometer COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Cénat, J.M.; Blais-Rochette, C.; Kokou-Kpolou, C.K.; Noorishad, P.-G.; Mukunzi, J.N.; McIntee, S.-E.; Dalexis, R.D.; Goulet, M.-A.; Labelle, P.R. Prevalence of Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, Insomnia, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Psychological Distress among Populations Affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 295, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, T.A.; Aiyenitaju, O.; Adekoya, O.D. The Work–Family Balance of British Working Women during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Work-Appl. Manag. 2021, 13, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, R.J.; Bezdek, J.C. Fuzzy C-Means Clustering of Incomplete Data. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part B Cybern. Publ. IEEE Syst. Man Cybern. Soc. 2001, 31, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scitovski, R.; Zekić Sušac, M.; Has, A. Searching for an Optimal Partition of Incomplete Data with Application in Modeling Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings. Croat. Oper. Res. Rev. 2018, 9, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birant, D.; Kut, A. ST-DBSCAN: An Algorithm for Clustering Spatial–Temporal Data. Data Knowl. Eng. 2007, 60, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.-P.; Xu, X. A Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Portland, OR, USA, 2–4 August 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mahesh Kumar, K.; Rama Mohan Reddy, A. A Fast DBSCAN Clustering Algorithm by Accelerating Neighbor Searching Using Groups Method. Pattern Recognit. 2016, 58, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scitovski, R.; Sabo, K. DBSCAN-like Clustering Method for Various Data Densities. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2020, 23, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scitovski, R.; Sabo, K. A Combination of K-Means and DBSCAN Algorithm for Solving the Multiple Generalized Circle Detection Problem. Adv. Data Anal. Classif. 2021, 15, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scitovski, R.; Sabo, K. Klaster Analiza i Prepoznavanje Geometrijskih Objekata; J. J. Strossmayer University of Osijek, Department of Mathematics: Osijek, Croatia, 2020; ISBN 978-953-8154-11-9. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, L.; Kearney, A.; Kirzinger, A.; Lopez, L.; Muñana, C.; Brodie, M. KFF Health Tracking Poll—July 2020; KFF: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, D. Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10). Available online: https://novopsych.com/assessments/well-being/perceived-stress-scale-pss-10/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Zefferino, R.; Fortunato, F.; Arsa, A.; Di Gioia, S.; Tomei, G.; Conese, M. Assessment of Stress Salivary Markers, Perceived Stress, and Shift Work in a Cohort of Fishermen: A Preliminary Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, H.; Ahlberg, J.; Sinisalo, J.; Hublin, C.; Hirvonen, A.; Partinen, M.; Sarna, S.; Savolainen, A. Morning Cortisol Levels and Perceived Stress in Irregular Shift Workers Compared with Regular Daytime Workers. Sleep Disord. 2012, 2012, 789274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcez, A.; Weiderpass, E.; Canuto, R.; Lecke, S.B.; Spritzer, P.M.; Pattussi, M.P.; Olinto, M.T.A. Salivary Cortisol, Perceived Stress, and Metabolic Syndrome: A Matched Case-Control Study in Female Shift Workers. Horm. Metab. Res. Horm. Stoffwechselforschung Horm. Metab. 2017, 49, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-H. Review of the Psychometric Evidence of the Perceived Stress Scale. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, M. Somatic Manifestation of Distress: Clinical Medicine, Psychological, and Public Health Perspectives. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2017, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi (Version 2.6). (Computer Software). 2024. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Version 4.4) (Computer Software). 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Revelle, W. Psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research [R Package]. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=psych (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Kudielka, B.M.; Kirschbaum, C. Sex Differences in HPA Axis Responses to Stress: A Review. Biol. Psychol. 2005, 69, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhart, M.; Chong, R.Y.; Oswald, L.; Lin, P.-I.; Wand, G.S. Gender Differences in Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) Axis Reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2006, 31, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milić, J.; Milić Vranješ, I.; Krajina, I.; Heffer, M.; Škrlec, I. Circadian Typology and Personality Dimensions of Croatian Students of Health-Related University Majors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Kudielka, B.M.; Gaab, J.; Schommer, N.C.; Hellhammer, D.H. Impact of Gender, Menstrual Cycle Phase, and Oral Contraceptives on the Activity of the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Psychosom. Med. 1999, 61, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Janicki-Deverts, D. Who’s Stressed? Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozović, D. Societal Collapse: A Literature Review. Futures 2023, 145, 103075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.M.; Tyrka, A.R.; Price, L.H.; Carpenter, L.L. Sex Differences in the Use of Coping Strategies: Predictors of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms. Depress. Anxiety 2008, 25, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodes, G.E.; Bangasser, D.; Sotiropoulos, I.; Kokras, N.; Dalla, C. Sex Differences in Stress Response: Classical Mechanisms and Beyond. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2024, 22, 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P. Gender Differences in Stress and Coping Styles. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebner, K.; Singewald, N. Individual Differences in Stress Susceptibility and Stress Inhibitory Mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 14, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, T.; de la Rubia, M.A.; Hincz, K.P.; Comas-Lopez, M.; Subirats, L.; Fort, S.; Sacha, G.M. Influence of COVID-19 Confinement on Students’ Performance in Higher Education. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X. The Relationship between Psychological Stress and Academic Performance among College Students: The Mediating Roles of Cognitive Load and Self-Efficacy. Acta Psychol. 2025, 259, 105433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Question | Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|

| In the last month, how often have you… | ||

| Factor 1. Perceived helplessness | ||

| 1 | been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? | 0.755 |

| 2 | felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? | 0.699 |

| 3 | felt nervous and “stressed”? | 0.745 |

| 6 | found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | 0.619 |

| 9 | been angered because of things that were outside of your control? | 0.644 |

| 10 | felt difficulties were accumulating so high that you could not overcome them? | 0.593 |

| Factor 2. Lack of self-efficacy | ||

| 4 | felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems? | 0.681 |

| 5 | felt that things were going your way? | 0.715 |

| 7 | been able to control irritations in your life? | 0.500 |

| 8 | felt that you were on top of things? | 0.632 |

| Males | Male Clusters | |||||

| π1 | π2 | π3 | π4 | π5 | ||

| Total scores | (n = 90) | (n = 46) | (n = 13) | (n = 17) | (n = 10) | (n = 4) |

| PSS-10 (mean ± SD) | * 14 ± 6 | 13.3 ± 5.5 | 13.5 ± 5.5 | 16.2 ± 6.8 | 14.7 ± 8.1 | 10.8 ± 7.4 |

| PH (median [Lq; Uq]) | † 6.5 (4; 10) | 6 (3; 10) | 8 (5; 10) | 7 (5; 17) | 9 (3; 14) | 7 (2; 9) |

| LSE (median [Lq; Uq]) | 6 (4; 9) | 6 (4; 9) | 5 (3; 8) | 6 (4; 9) | 6 (3; 7) | 5 (1; 8) |

| Females | Female Clusters | |||||

| π1 | π2 | π3 | π4 | π5 | ||

| Total scores | (n = 87) | (n = 58) | (n = 6) | (n = 14) | (n = 2) | (n = 7) |

| PSS-10 (mean ± SD) | * 16 ± 6 | 15.8 ± 6.1 | 16.5 ± 4.8 | 15.1 ± 4.4 | 15 ± 1.4 | 19.3 ± 9.9 |

| PH (median [Lq; Uq]) | † 9 (6; 13) | 9 (6; 13) | 10 (8; 13) | 8 (6; 9) | 8 (8; 8) | 9 (7; 21) |

| LSE (median [Lq; Uq]) | 6 (5; 9) | 6 (4; 9) | 7 (2; 9) | 7 (6; 10) | 7 (6; 8) | 6 (5; 11) |

| Males | Male | Clusters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | π1 | π2 | π3 | π4 | π5 | |

| In the last month how often have you… | (n = 90) | (n = 46) | (n = 13) | (n = 17) | (n = 10) | (n = 4) |

| PH subscale | ||||||

| (1) been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? | 1 (0; 2) | a 1 (0; 1.3) | 1 (0; 2) | 2 (0; 2) | 1.5 (0; 3.3) | 1.5 (0.25; 2) |

| (2) felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? | f 1 (0; 2) | b 0 (0; 2) | 1 (0; 2) | c 1 (0; 2.5) | 0.5 (0; 2.3) | 1 (0.25; 1.8) |

| (3) felt nervous and “stressed”? | 1 (0; 2) | 1 (0; 2) | 2 (1; 2) | 2 (1; 3) | 1.5 (0; 2) | 0.5 (0; 1) |

| (6) found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | 1 (0; 2) | 1 (0; 2) [n = 44] | 1 (0.5; 2) | 2 (0.5; 3) | 2 (0.75; 2.3) | 1 (0.25; 1.8) |

| (9) been angered because of things that were outside of your control? | g 2 (0; 2) | 1 (0; 2) | 2 (0; 2) | 2 (0.5; 3) | 2 (0.75; 2.5) | d 1 (1; 1) |

| (10) felt difficulties were accumulating so high that you could not overcome them? | 1 (0; 2) | 1 (0; 2) | 1 (1; 2) | 1 (0; 2.5) | 1 (0.75; 2.3) | 1 (0.25; 2.5) |

| LSE subscale | ||||||

| (4) felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems? | 3 (2; 4) | 3 (2; 4) | 3 (3; 4) | 3 (2; 4) | 3 (3; 4) | 3.5 (3; 4) |

| (5) felt that things were going your way? | 3 (2; 3) | 2 (2; 3) [n = 44] | e 3 (2; 3) | 2 (1; 3) | 3 (2; 3.3) | 3.5 (2.3; 4) |

| (7) been able to control irritations in your life? | 3 (1; 3) | 2 (1; 3) | 3 (2; 3.5) | 3 (2; 3) | 3 (1; 3) | 2 (0.25; 3.8) |

| (8) felt that you were on top of things? | 2 (2; 3) | 2 (2; 3) [n = 45] | 2.5 (2; 3) [n = 12] | 2 (1; 3) | 2.5 (1.8; 3.3) | 2.5 (1.3; 3.8) |

| Females | Female | Clusters | ||||

| Question | π1 | π2 | π3 | π4 | π5 | |

| In the last month how often have you… | (n = 87) | (n = 58) | (n = 6) | (n = 14) | (n = 2) | (n = 7) |

| PH subscale | ||||||

| (1) been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? | 2 (0; 2) | a 2 (0; 2.3) | 2 (1.8; 2) | 1 (0; 2) | 1 (0; 2) | 2 (0; 4) |

| (2) felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? | f 2 (0; 2) | b 1.5 (0; 2) | 1.5 (1; 2.3) | c 1.5 (0; 2) | 2 (2; 2) | 1 (0; 2) |

| (3) felt nervous and “stressed”? | 2 (1; 2) | 2 (1; 2) | 2.5 (1.8; 3) | 1 (0; 2) | 1.5 (1; 2) | 2 (0; 4) |

| (6) found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | 2 (0; 2) | 1 (0; 2) | 2 (0.75; 3) | 2 (0; 2) | 1.5 (1; 2) | 2 (0; 3) |

| (9) been angered because of things that were outside of your control? | g 2 (1; 2) | 3 (2; 3) [n = 57] | 2 (1; 2.3) | 2 (1; 2) | 1.5 (1; 2) | d 2 (2; 3) |

| (10) felt difficulties were accumulating so high that you could not overcome them? | 1 (0; 2) | 1 (1; 2) | 1 (0; 1.5) | 1 (0; 2) | 0.5 (0; 1) | 3 (0; 3) |

| LSE subscale | ||||||

| (4) felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems? | 3 (2; 4) | 3 (2; 4) | 2.5 (1; 4) | 2.5 (1.8; 3) | 2 (1; 3) | 3 (1; 4) |

| (5) felt that things were going your way? | 2 (1; 3) | 2 (2; 3) | e 2 (1; 3) | 2 (1.8; 3) | 2.5 (2; 3) | 2 (1; 2) |

| (7) been able to control irritations in your life? | 2 (2; 3) | 3 (2; 3) | 2.5 (2; 4) | 2 (1; 3) | 1 (0; 2) | 2 (1; 3) |

| (8) felt that you were on top of things? | 2 (1; 3) | 2 (1; 3) [n = 57] | 3 (1.8; 3.3) | 2 (1; 3) | 3.5 (3; 4) | 2 (1; 2) |

| Question | No | Yes | NA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Do you experience sleep problems? | 80.8 | 19.2 | 0.0 |

| 2 | Do you experience poor appetite? | 93.8 | 5.1 | 1.1 |

| 3 | Do you experience overeating? | 88.1 | 11.9 | 0.0 |

| 4 | Do you have more frequent headaches? | 85.3 | 14.7 | 0.0 |

| 5 | Do you have more frequent stomachaches? | 95.5 | 4.5 | 0.0 |

| 6 | Do you experience tamper control (angrier) difficulties? | 85.9 | 13.6 | 0.6 |

| 7 | Do you experience increased alcohol use? | 87.6 | 0.6 | 11.9 |

| 8 | Do you experience increased drug use? | 92.7 | 0.0 | 7.3 |

| 9 | If you have some illness, do you experience worsening of your conditions? | 93.8 | 4.0 | 2.3 |

| 10 | Any of the above listed | 62.1 | 37.9 | 0.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ivić, V.; Labak, I.; Shevchuk, O.; Scitovski, R.; Ivankiv, V.; Kozak, K.; Korda, M.; Heffer, M.; Vari, S.G. Sex-Specific Patterns of Cortisol Fluctuation, Stress, and Academic Success in Quarantined Foreign Medical Students During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Life 2026, 16, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010054

Ivić V, Labak I, Shevchuk O, Scitovski R, Ivankiv V, Kozak K, Korda M, Heffer M, Vari SG. Sex-Specific Patterns of Cortisol Fluctuation, Stress, and Academic Success in Quarantined Foreign Medical Students During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Life. 2026; 16(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvić, Vedrana, Irena Labak, Oksana Shevchuk, Rudolf Scitovski, Viktoria Ivankiv, Kateryna Kozak, Mykhaylo Korda, Marija Heffer, and Sandor G. Vari. 2026. "Sex-Specific Patterns of Cortisol Fluctuation, Stress, and Academic Success in Quarantined Foreign Medical Students During the COVID-19 Lockdown" Life 16, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010054

APA StyleIvić, V., Labak, I., Shevchuk, O., Scitovski, R., Ivankiv, V., Kozak, K., Korda, M., Heffer, M., & Vari, S. G. (2026). Sex-Specific Patterns of Cortisol Fluctuation, Stress, and Academic Success in Quarantined Foreign Medical Students During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Life, 16(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010054