High-Intensity Interval Training Attenuates Inflammation in Cardiorenal Syndrome Induced by Renal Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

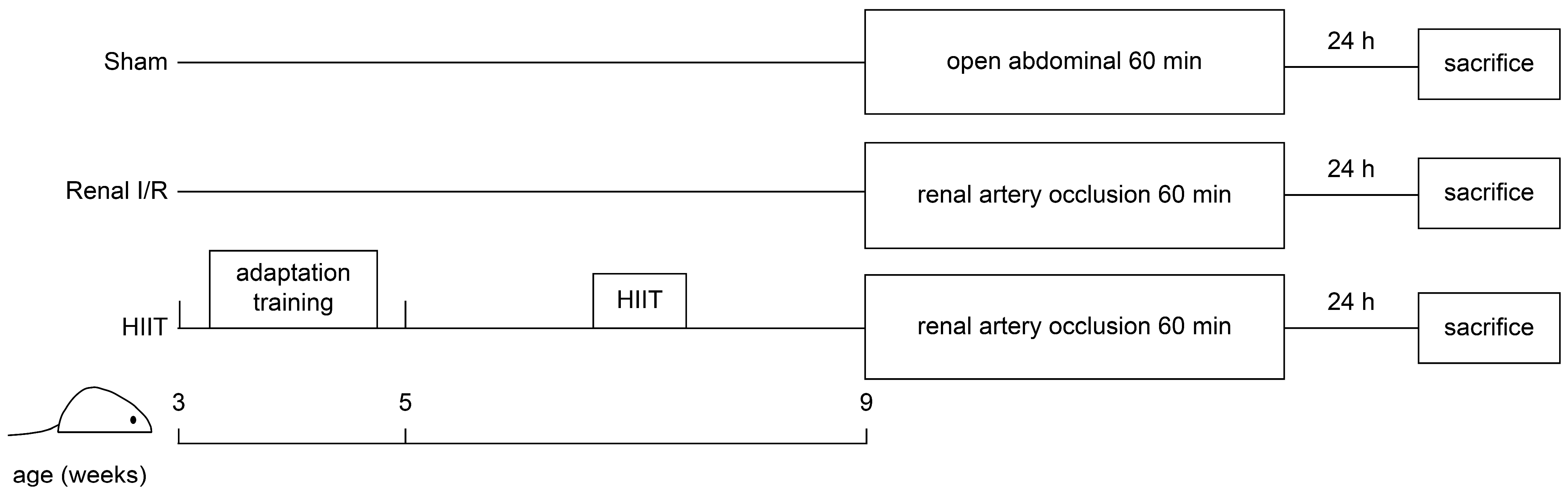

2.1. Animals Preparation and Protocol

2.2. HIIT Intervention

2.3. Renal I/R

2.4. Biochemical Study

2.5. Histological Examination

2.6. Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL) Assay

2.7. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent (ELISA) Analysis

2.8. Western Blotting Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mortality and Hemodynamic Changes

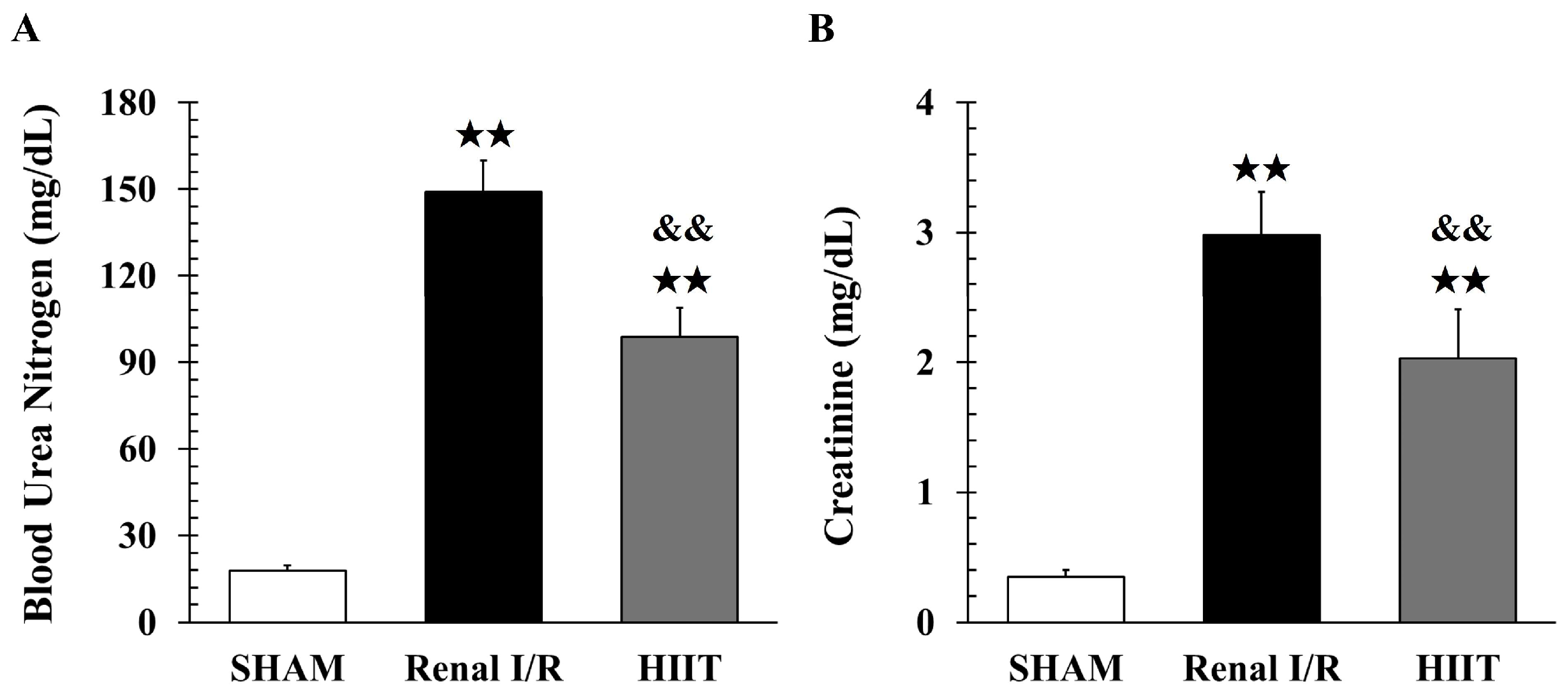

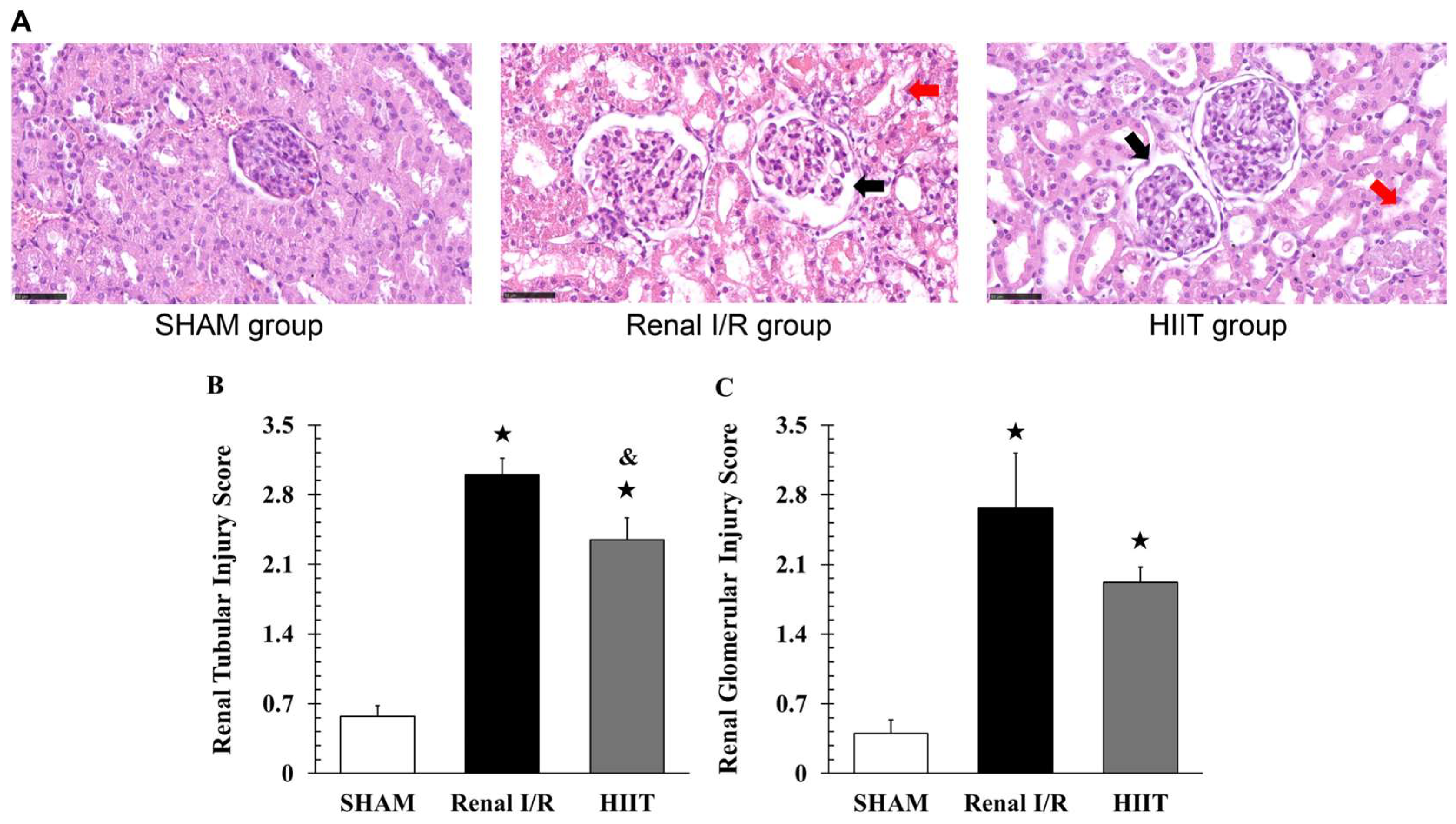

3.2. Analysis of Renal Injury

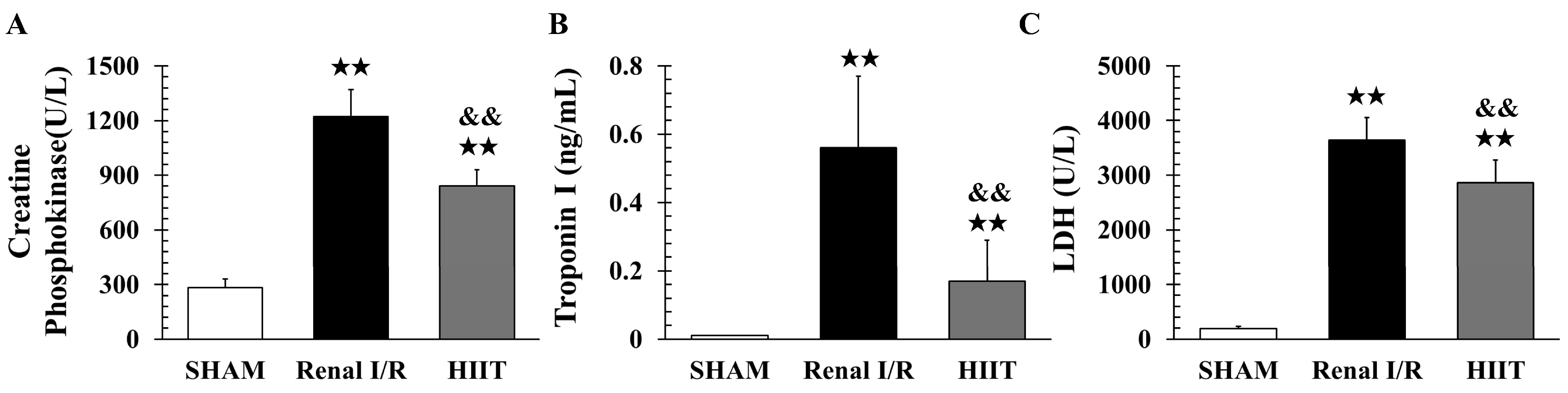

3.3. Biochemical Analysis of Myocardial Injury

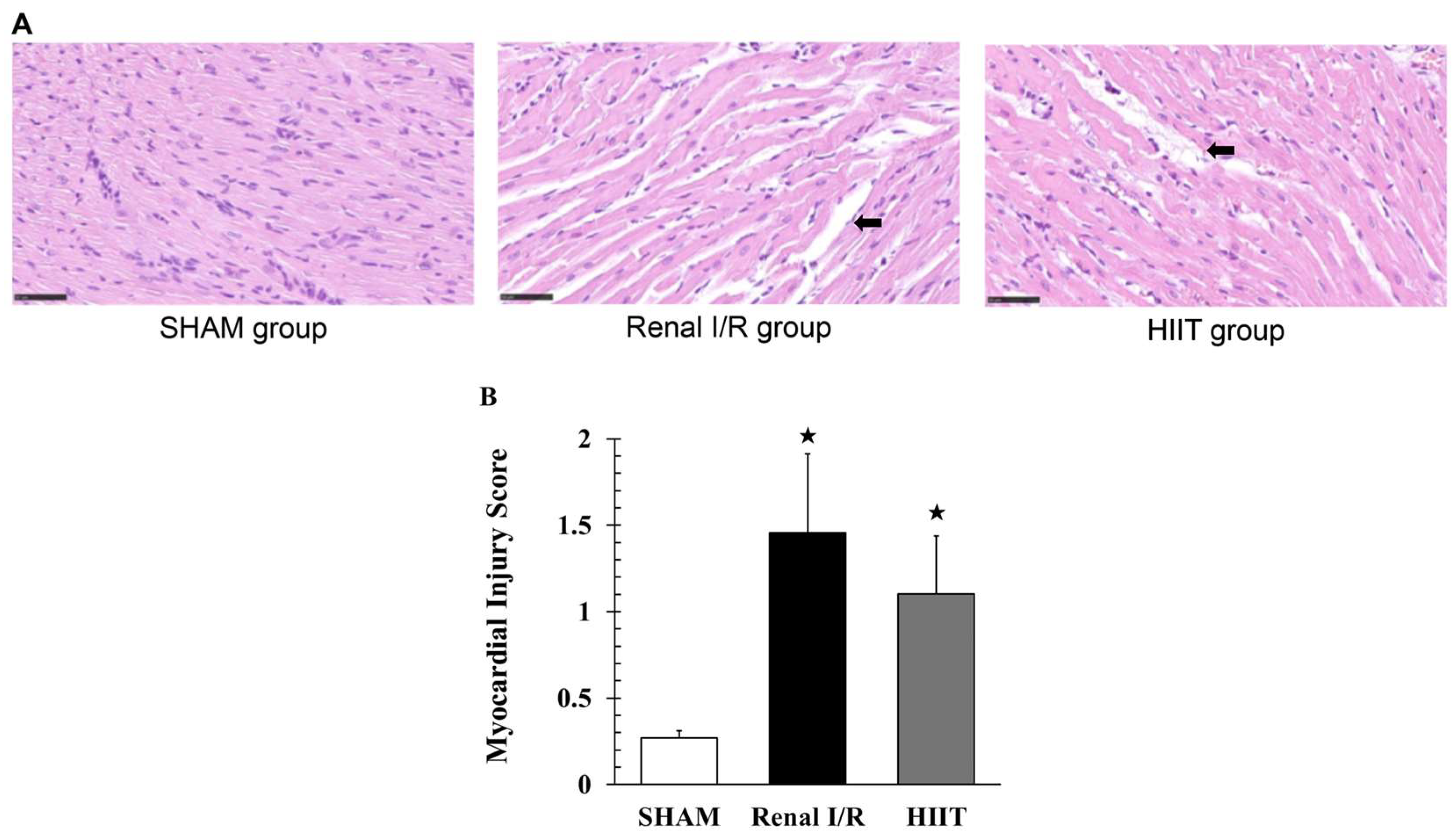

3.4. Histological Examination of Myocardial Injury

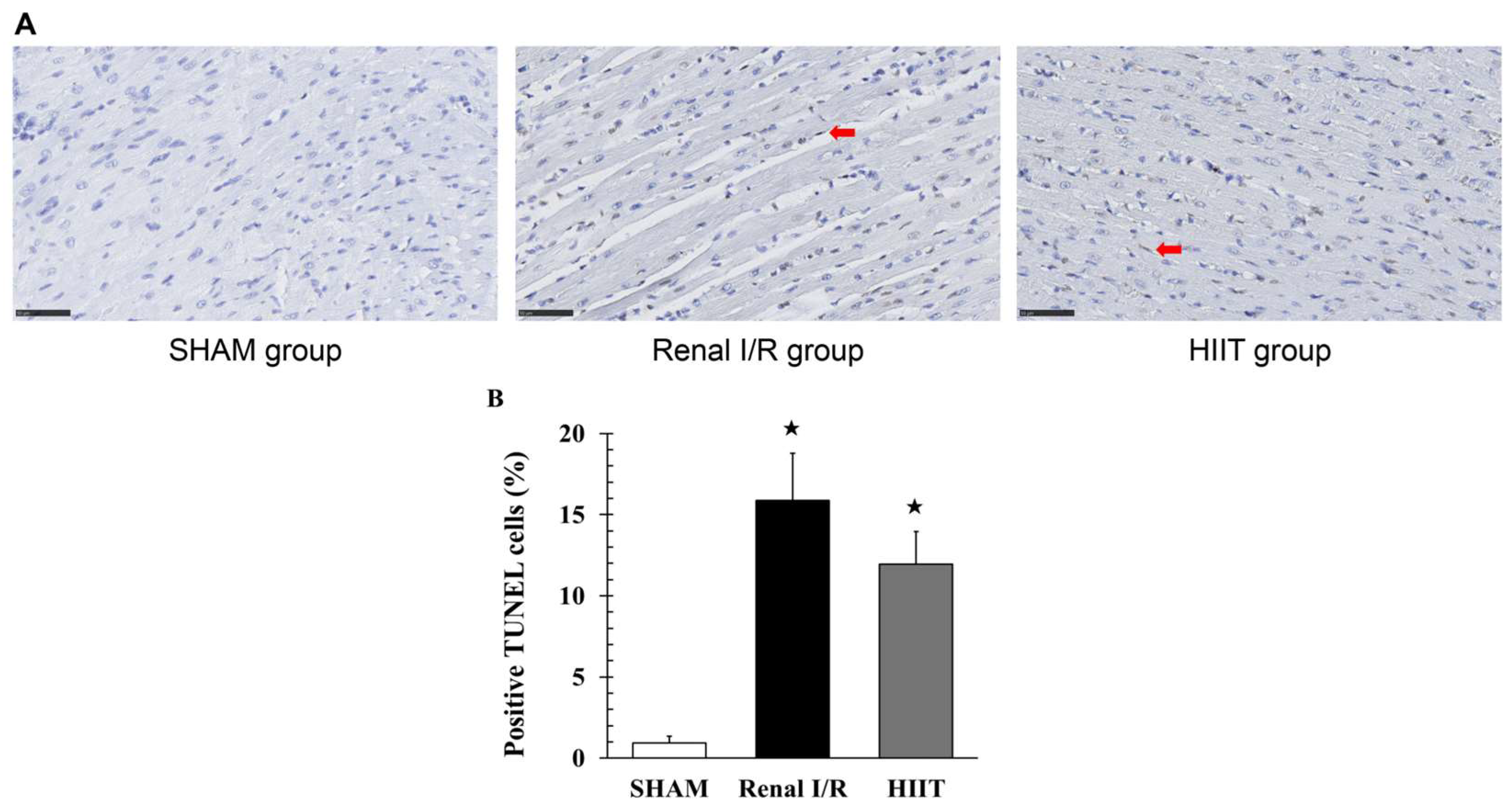

3.5. TUNEL Staining Analysis of the Myocardium

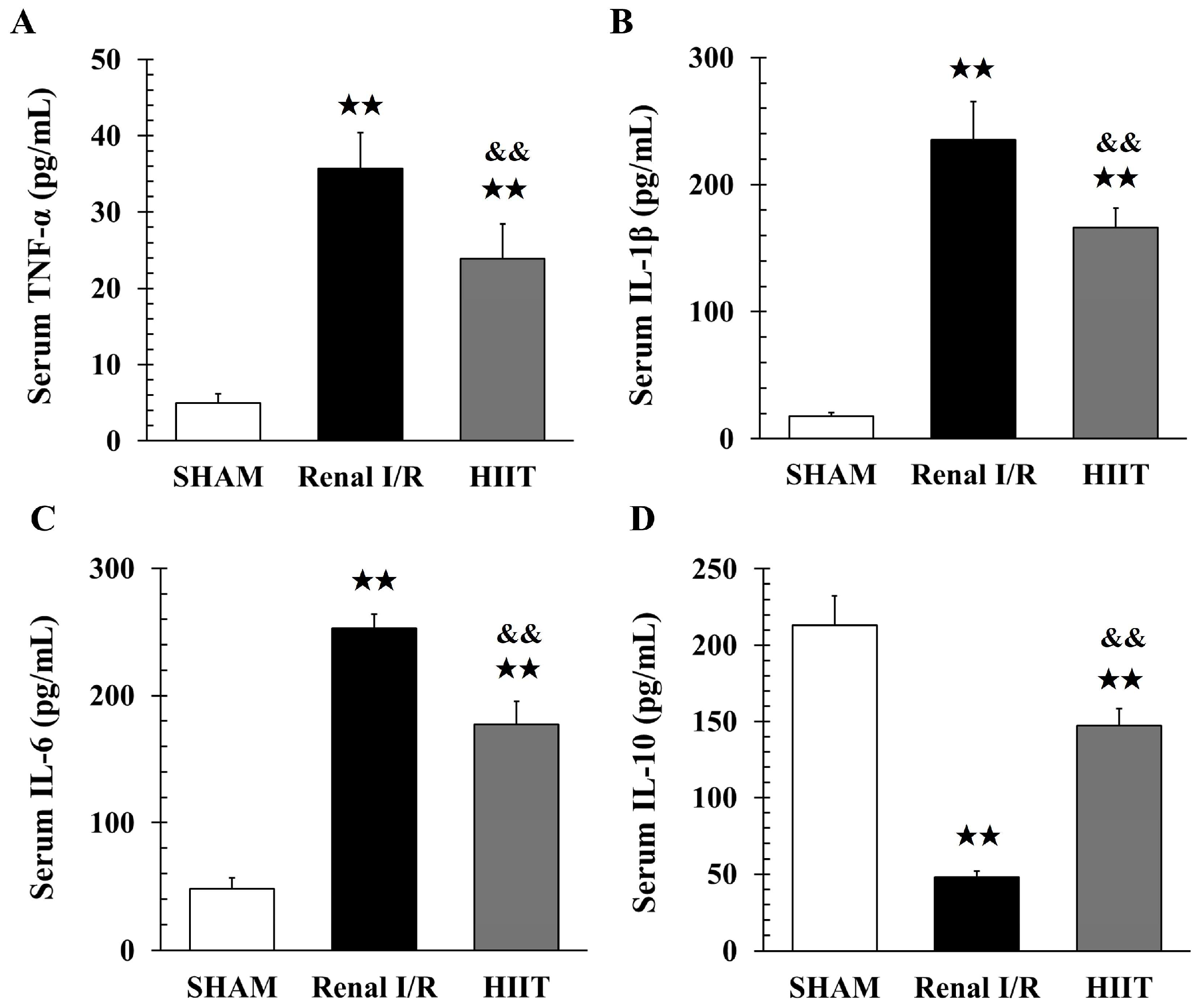

3.6. Analysis of Inflammatory Factors

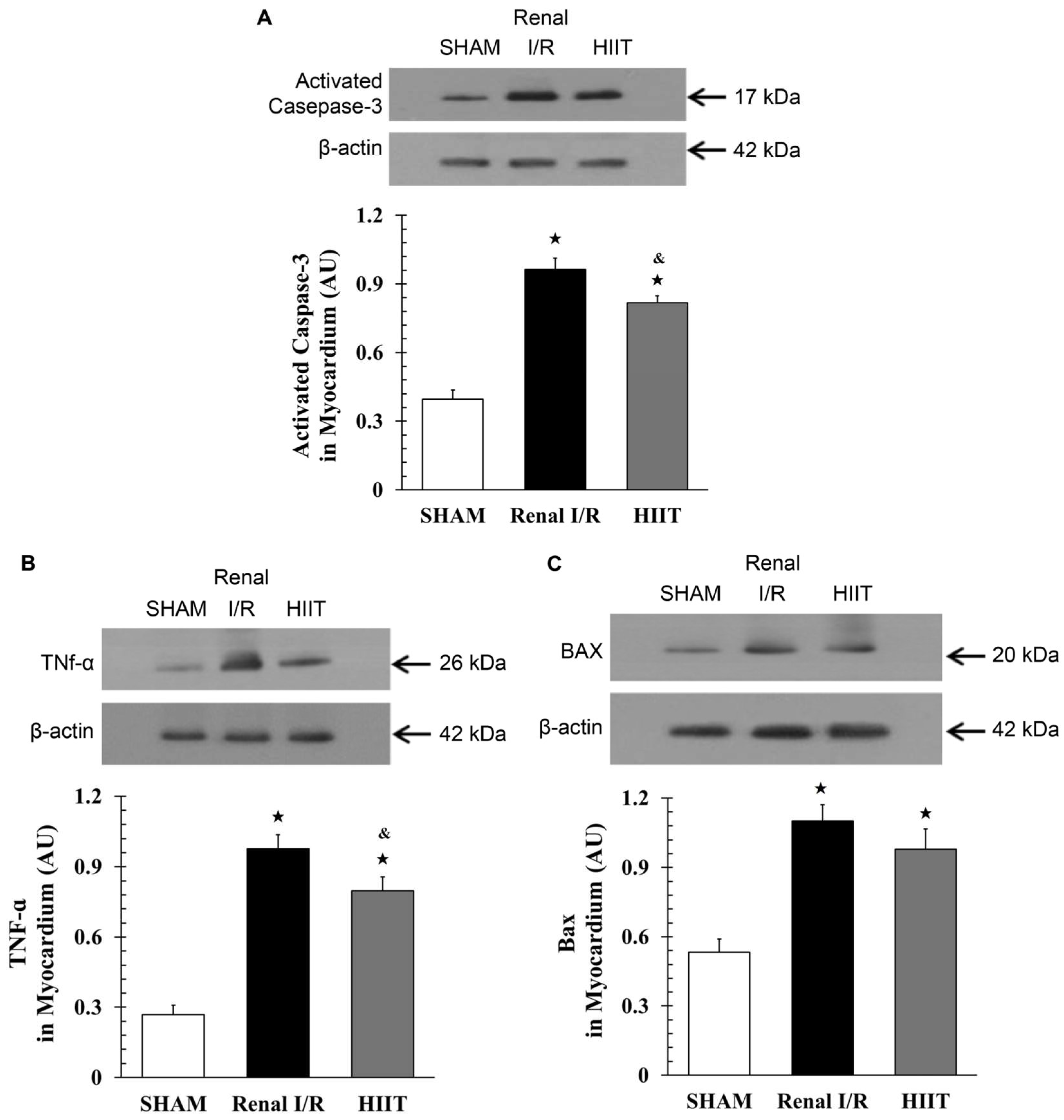

3.7. Cardiac Western Blot Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute kidney injury |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| CPK | creatine phosphokinase |

| cTnI | cardiac troponin I |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked Immunosorbent |

| eNOS | endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| HIIT | high-intensity interval training |

| IL | interleukin |

| I/R | ischemia–reperfusion |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TUNEL | Transferase dUTP Nick-end Labeling |

References

- Hauet, T.; Pisani, D.F. New strategies protecting from ischemia/reperfusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowled, P.; Fitridge, R. Pathophysiology of reperfusion injury. In Mechanisms of Vascular Disease: A Textbook for Vascular Specialists; Fitridge, R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.J.; Lee, H.T. Mechanisms and therapeutic targets of ischemic acute kidney injury. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 38, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueler, F.; Gwinner, W.; Schwarz, A.; Haller, H. Long-term effects of acute ischemia and reperfusion injury. Kidney Int. 2004, 66, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, M.C.; Pavan, N.; Parekh, D.J. Current paradigm for ischemia in kidney surgery. J. Urol. 2016, 195, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Avondt, K.; Nur, E.; Zeerleder, S. Mechanisms of haemolysis-induced kidney injury. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 671–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglarnia, A.R.; Huber-Lang, M.; Mohlin, C.; Ekdahl, K.N.; Nilsson, B. The multifaceted role of complement in kidney transplantation. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.L.; Jaber, B.L.; Faubel, S.; Chawla, L.S. Acute Kidney Injury Advisory Group of American Society of Nephrology. AKI transition of care: A potential opportunity to detect and prevent CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellum, J.A.; Romagnani, P.; Ashuntantang, G.; Ronco, C.; Zarbock, A.; Anders, H.J. Acute kidney injury. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, K.L.; Silva Júnior, G.B.; Barreto, A.G.; Melo, F.M.; Oliveira, B.B.; Mota, R.M.; Rocha, N.A.; Silva, S.L.; Araújo, S.M.; Daher, E.F. Acute kidney injury after trauma: Prevalence, clinical characteristics and RIFLE classification. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 14, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, S.A.; Harel, Z.; McArthur, E.; Nash, D.M.; Acedillo, R.; Kitchlu, A.; Garg, A.X.; Chertow, G.M.; Bell, C.M.; Wald, R. Causes of death after a hospitalization with AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, J.S.; Welsh, C.E.; Celis-Morales, C.A.; Mackay, D.; Lewsey, J.; Gray, S.R.; Lyall, D.M.; Cleland, J.G.; Gill, J.M.; Jhund, P.S.; et al. Glomerular filtration rate by differing measures, albuminuria and prediction of cardiovascular disease, mortality and end-stage kidney disease. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajibowo, A.O.; Okobi, O.E.; Emore, E.; Soladoye, E.; Sike, C.G.; Odoma, V.A.; Bakare, I.O.; Kolawole, O.A.; Afolayan, A.; Okobi, E.; et al. Cardiorenal syndrome: A literature review. Cureus 2023, 15, e41252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buliga-Finis, O.N.; Ouatu, A.; Badescu, M.C.; Dima, N.; Tanase, D.M.; Richter, P.; Rezus, C. Beyond the cardiorenal syndrome: Pathophysiological approaches and biomarkers for renal and cardiac crosstalk. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangaswami, J.; Bhalla, V.; Blair, J.E.; Chang, T.I.; Costa, S.; Lentine, K.L.; Lerma, E.V.; Mezue, K.; Molitch, M.; Mullens, W.; et al. Cardiorenal syndrome: Classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment strategies: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019, 139, e840–e878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, G.P. Trauma of major surgery: A global problem that is not going away. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 81, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.N.; Crawford, M.D. Coronary heart disease and physical activity of work; evidence of a national necropsy survey. Br. Med. J. 1958, 2, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, D.H.; Uthman, L.; Somani, Y.; van Royen, N. Short-term exercise-induced protection of cardiovascular function and health: Why and how fast does the heart benefit from exercise? J. Physiol. 2022, 600, 1339–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doustar, Y.; Soufi, F.G.; Jafary, A.; Saber, M.M.; Ghiassie, R. Role of four-week resistance exercise in preserving the heart against ischaemia-reperfusion-induced injury. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2012, 23, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, Y.; Guan, L.; Elkin, K.; Xiao, J. Targets identified from exercised heart: Killing multiple birds with one stone. NPJ Regen. Med. 2021, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.Y.; Yiang, G.T.; Liao, W.T.; Tsai, A.P.; Cheng, Y.L.; Cheng, P.W.; Li, C.Y.; Li, C.J. Current mechanistic concepts in ischemia and reperfusion injury. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 46, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Sun, Y.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, Z.; Gao, C.; Feng, P.; Zhang, X.; Yi, W.; Gao, F. Short-duration swimming exercise after myocardial infarction attenuates cardiac dysfunction and regulates mitochondrial quality control in aged mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 4079041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.A.; Jew, K.N.; Sparagna, G.C.; Musch, T.I.; Moore, R.L. Exercise training preserves coronary flow and reduces infarct size after ischemia-reperfusion in rat heart. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 95, 2510–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, P.A.; Boidin, M.; Juneau, M.; Nigam, A.; Gayda, M. High-intensity interval training in patients with coronary heart disease: Prescription models and perspectives. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 60, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Xing, J.; Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liu, G. The effects of high-intensity interval training on exercise capacity and prognosis in heart failure and coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 2022, 4273809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balligand, J.L.; Feron, O.; Dessy, C. eNOS activation by physical forces: From short-term regulation of contraction to chronic remodeling of cardiovascular tissues. Physiol. Rev. 2009, 89, 481–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Trager, L.E.; Liu, X.; Hastings, M.H.; Xiao, C.; Guerra, J.; To, S.; Li, G.; Yeri, A.; Rodosthenous, R.; et al. lncExACT1 and DCHS2 regulate physiological and pathological cardiac growth. Circulation 2022, 145, 1218–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, N.R.; De Biase, N.; Conte, L.; Gargani, L.; Mazzola, M.; Fabiani, I.; Natali, A.; Dini, F.L.; Frumento, P.; Rosada, J.; et al. Cardiac reserve and exercise capacity: Insights from combined cardiopulmonary and exercise echocardiography stress testing. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2021, 34, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Deng, J.; Yao, J.; Song, J.; Meng, D.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, M.; Liang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sluijter, J.P.; et al. Exercise downregulates HIPK2 and HIPK2 inhibition protects against myocardial infarction. EBiomedicine 2021, 74, 103713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portier, H.; Benaitreau, D.; Pallu, S. Does physical exercise always improve bone quality in rats? Life 2020, 10, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xiao, J.; Zhu, H.; Wei, X.; Platt, C.; Damilano, F.; Xiao, C.; Bezzerides, V.; Boström, P.; Che, L.; et al. miR-222 is necessary for exercise-induced cardiac growth and protects against pathological cardiac remodeling. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Fu, S.K.; Tai, H.L.; Tseng, K.W.; Tang, C.Y.; Yu, C.H.; Lai, C.C. A comparative study: Cardioprotective effects of high-intensity interval training versus ischaemic preconditioning in rat myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion. Life 2024, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinnis, G.R.; Ballmann, C.; Peters, B.; Nanayakkara, G.; Roberts, M.; Amin, R.; Quindry, J.C. Interleukin-6 mediates exercise preconditioning against myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 308, H1423–H1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesherwani, V.; Chavali, V.; Hackfort, B.T.; Tyagi, S.C.; Mishra, P.K. Exercise ameliorates high fat diet induced cardiac dysfunction by increasing interleukin 10. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalafi, M.; Sakhaei, M.H.; Kazeminasab, F.; Symonds, M.E.; Rosenkranz, S.K. The impact of high-intensity interval training on vascular function in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1046560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nystoriak, M.A.; Bhatnagar, A. Cardiovascular effects and benefits of exercise. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; Chen, R.; Wu, X.; Ni, G.; Liu, C.; Das, S.; Sluijter, J.P.; et al. ADAR2 increases in exercised heart and protects against myocardial infarction and doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.D.; Gebhart, G.F.; Gonder, J.C.; Keeling, M.E.; Kohn, D.F. Special report: The 1996 guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. ILAR J. 1997, 38, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamat, F.A.; Oudman, I.; Haan, Y.C.; van Kuilenburg, A.B.; Leen, R.; Danser, J.A.; Leijten, F.P.; Ris-Stalpers, C.; van Montfrans, G.A.; Clark, J.F.; et al. Creatine kinase inhibition lowers systemic arterial blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats: A randomized controlled trial. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 2418–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, P.S.; Briskey, D.R.; Scanlan, A.T.; Coombes, J.S.; Dalbo, V.J. High intensity interval training favourably affects antioxidant and inflammation mRNA expression in early-stage chronic kidney disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingarelli, B.; Salzman, A.L.; Szabó, C. Genetic disruption of poly (ADP-ribose) synthetase inhibits the expression of P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 1998, 83, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, C.B.; Hsu, C.P.; Tsao, N.W.; Lai, S.T.; Huang, C.H. Effects of verapamil on coronary vascular resistance in rabbits: Measurement with pulsed Doppler velocimetry. Chin. Med. J. 2001, 64, 715–720. [Google Scholar]

- Go, A.S.; Hsu, C.Y.; Yang, J.; Tan, T.C.; Zheng, S.; Ordonez, J.D.; Liu, K.D. Acute kidney injury and risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic events. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 13, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odutayo, A.; Wong, C.X.; Farkouh, M.; Altman, D.G.; Hopewell, S.; Emdin, C.A.; Hunn, B.H. AKI and long-term risk for cardiovascular events and mortality. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 28, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feltes, C.M.; Van Eyk, J.; Rabb, H. Distant-organ changes after acute kidney injury. Nephron Physiol. 2008, 109, p80–p84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, J.; Hjelmesaeth, J.; Hertel, J.K.; Gjevestad, E.; Småstuen, M.C.; Johnson, L.K.; Martins, C.; Andersen, E.; Helgerud, J.; Støren, Ø. Effect of aerobic exercise intensity on energy expenditure and weight loss in severe obesity—A randomized controlled trial. Obesity 2021, 29, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; He, J.; Cui, J.; Li, H.; Men, J. The effects of aerobic exercise combined with resistance training on inflammatory factors and heart rate variability in middle-aged and elderly women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2022, 27, e12996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibben, G.; Faulkner, J.; Oldridge, N.; Rees, K.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 11, CD001800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börjesson, M.; Onerup, A.; Lundqvist, S.; Dahlöf, B. Physical activity and exercise lower blood pressure in individuals with hypertension: Narrative review of 27 RCTs. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, M. Physical activity and exercise training in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 40, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Y.; Lai, C.C.; Huang, P.H.; Yang, A.H.; Chiang, S.C.; Huang, P.C.; Tseng, K.W.; Huang, C.H. Magnolol reduces myocardial injury induced by renal ischemia and reperfusion. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2022, 85, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, S.; Bai, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Y. Exercise training and chronic kidney disease: Characterization and bibliometrics of citation classics of clinical intervention trials. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2349187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, N.; Sharma, N.; Kulkarni, Y.A.; Mulay, S.R.; Gaikwad, A.B. Renal ischemia/reperfusion injury: An insight on in vitro and in vivo models. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prem, P.N.; Kurian, G.A. Does cardiac impairment develop in ischemic renal surgery in rats depending on the reperfusion time? Heliyon 2024, 10, e31389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bufi, R.; Korstanje, R. The impact of genetic background on mouse models of kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Clef, N.; Verhulst, A.; D’Haese, P.C.; Vervaet, B.A. Unilateral renal ischemia-reperfusion as a robust model for acute to chronic kidney injury in mice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.; Dong, Z. Mouse model of ischemic acute kidney injury: Technical notes and tricks. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2012, 303, F1487–F1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, M.A.; Weinberg, J.M. The conundrum of protection from AKI by adenosine in rodent clamp ischemia models. Kidney Int. 2013, 84, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, K. Improved cardiac function following ischemia reperfusion injury using exercise preconditioning and L-arginine supplementation via oxidative stress mitigation and angiogenesis amelioration. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2022, 22, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatahi, A.; Zarrinkalam, E.; Azizbeigi, K.; Ranjbar, K. Cardioprotective effects of exercise preconditioning on ischemia-reperfusion injury and ventricular ectopy in young and senescent rats. Exp. Gerontol. 2022, 162, 111758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, G.O.; Frantz, E.D.; Magliano, D.C.; Bargut, T.C.; Sepúlveda-Fragoso, V.; Silvares, R.R.; Daliry, A.; do Nascimento, A.R.; Borges, J.P. Effects of short-term high-intensity interval and continuous exercise training on body composition and cardiac function in obese sarcopenic rats. Life Sci. 2020, 256, 117920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramez, M.; Rajabi, H.; Ramezani, F.; Naderi, N.; Darbandi-Azar, A.; Nasirinezhad, F. The greater effect of high-intensity interval training versus moderate-intensity continuous training on cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury through klotho levels and attenuate of myocardial TRPC6 expression. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2019, 19, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, R.; Damirchi, A.; Salehi, I.; Komaki, A.; Esposito, F. Mitochondrial dynamics as an underlying mechanism involved in aerobic exercise training-induced cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Life Sci. 2018, 213, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonizakis, M.; Moss, J.; Gilbert, S.; Broom, D.; Foster, J.; Tew, G.A. Low-volume high-intensity interval training rapidly improves cardiopulmonary function in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2014, 21, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Bei, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, J.; Chen, P.; Shen, S.; Xiao, J.; Li, X. Exercise training protects against acute myocardial infarction via improving myocardial energy metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 37, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, B.C.; Weeks, K.L.; Pretorius, L.; McMullen, J.R. Molecular distinction between physiological and pathological cardiac hypertrophy: Experimental findings and therapeutic strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 128, 191–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boström, P.; Mann, N.; Wu, J.; Quintero, P.A.; Plovie, E.R.; Panáková, D.; Gupta, R.K.; Xiao, C.; MacRae, C.A.; Rosenzweig, A.; et al. C/EBPβ controls exercise-induced cardiac growth and protects against pathological cardiac remodeling. Cell 2010, 143, 1072–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; Jeon, H.E.; Kim, W.H.; Joa, K.L.; Lee, H. Effect of maximal-intensity and high-intensity interval training on exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with acute myocardial infarction: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 60, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, H.A.; Bell, G.J. The interactions of intensity, frequency and duration of exercise training in altering cardiorespiratory fitness. Sports Med. 1986, 3, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glisic, M.; Nikolic Turnic, T.; Zivkovic, V.; Pindovic, B.; Chichkova, N.V.; Fisenko, V.P.; Nikolic, M.; Stijak, L.; Yurievna, L.E.; Veselinovic, M.; et al. The enhanced effects of swimming and running preconditioning in an experimental model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Medicina 2023, 59, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, A.S.; Guru, S.K.; Verma, M.K.; Sharma, C.; Abdullah, S.T.; Malik, F.; Chandra, S.; Katoch, M.; Bhushan, S. Disruption of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade and induction of apoptosis in HL-60 cells by an essential oil from monarda citriodora. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 62, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wang, H.; Peng, J. Hispidulin induces apoptosis through mitochondrial dysfunction and inhibition of P13k/Akt signalling pathway in HepG2 cancer cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 69, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; McMullen, J.R.; Sobkiw, C.L.; Zhang, L.; Dorfman, A.L.; Sherwood, M.C.; Logsdon, M.N.; Horner, J.W.; DePinho, R.A.; Izumo, S.; et al. Class IA phosphoinositide 3-kinase regulates heart size and physiological cardiac hypertrophy. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 9491–9502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, J.R.; Shioi, T.; Zhang, L.; Tarnavski, O.; Sherwood, M.C.; Kang, P.M.; Izumo, S. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (p110α) plays a critical role for the induction of physiological, but not pathological, cardiac hypertrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 12355–12360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Shi, D.; Guo, M. The roles of PKC-δ and PKC-ε in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 170, 105716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, V.A.; Benton, C.R.; Yan, Z.; Bonen, A. PGC-1alpha regulation by exercise training and its influences on muscle function and insulin sensitivity. Am. J. Physiol. -Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 299, E145–E161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freimann, S.; Scheinowitz, M.; Yekutieli, D.; Feinberg, M.S.; Eldar, M.; Kessler-Icekson, G. Prior exercise training improves the outcome of acute myocardial infarction in the rat. Heart structure, function, and gene expression. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 45, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plecevic, S.; Jakovljevic, B.; Savic, M.; Zivkovic, V.; Nikolic, T.; Jeremic, J.; Milosavljevic, I.; Srejovic, I.; Tasic, N.; Djuric, D.; et al. Comparison of short-term and medium-term swimming training on cardiodynamics and coronary flow in high salt-induced hypertensive and normotensive rats. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 447, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, K.D.; Dubberley, J.B.; McKelvie, R.S.; MacDonald, M.J. Low-volume, high-intensity interval training in patients with CAD. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisløff, U.; Støylen, A.; Loennechen, J.P.; Bruvold, M.; Rognmo, Ø.; Haram, P.M.; Tjønna, A.E.; Helgerud, J.; Slørdahl, S.A.; Lee, S.J.; et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: A randomized study. Circulation 2007, 115, 3086–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molmen-Hansen, H.E.; Stolen, T.; Tjonna, A.E.; Aamot, I.L.; Ekeberg, I.S.; Tyldum, G.A.; Wisloff, U.; Ingul, C.B.; Stoylen, A. Aerobic interval training reduces blood pressure and improves myocardial function in hypertensive patients. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2012, 19, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitranun, W.; Deerochanawong, C.; Tanaka, H.; Suksom, D. Continuous vs. interval training on glycemic control and macro- and microvascular reactivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, e69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, D.H.; Dawson, E.A.; Black, M.A.; Hopman, M.T.; Cable, N.T.; Green, D.J. Brachial artery blood flow responses to different modalities of lower limb exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endemann, D.H.; Schiffrin, E.L. Endothelial dysfunction. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 1983–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulghobra, D.; Dubois, M.; Alpha-Bazin, B.; Coste, F.; Olmos, M.; Gayrard, S.; Bornard, I.; Meyer, G.; Gaillard, J.C.; Armengaud, J.; et al. Increased protein S-nitrosylation in mitochondria: A key mechanism of exercise-induced cardioprotection. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2021, 116, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, C.; Nascimento, A.; Bolea, G.; Meyer, G.; Gayrard, S.; Lacampagne, A.; Cazorla, O.; Reboul, C. Key role of endothelium in the eNOS-dependent cardioprotection with exercise training. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2017, 102, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. Aerobic exercise ameliorates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and thrombosis of diabetic rats via activation of AMPK/Sirt1/PGC-1α pathway. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2022, 41, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Stage (Week) | Speed (m/min) | Incline (°) | Duration (min) | Interval | Frequency (Bouts/Week) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 20 | 5 | 30 | 2 min rest + 1 min sprint × 10 | 4 |

| 4 | 30 | 10 | 30 | ||

| 5–8 | 50 | 10 | 30 |

| Group | Sham | Renal Ischemia/Reperfusion | High-Intensity Interval Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rats allocated | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Deaths recorded | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Final sample size | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure, mmHg | Heart Rate, Beats/min | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Sham | Renal (I/R) | HIIT | Sham | Renal (I/R) | HIIT |

| Baseline 1 | 105 ± 4 | 104 ± 3 | 102 ± 5 | 457 ± 15 | 454 ± 22 | 454 ± 28 |

| Baseline 2 | 104 ± 3 | 106 ± 5 | 104 ± 4 | 459 ± 21 | 458 ± 27 | 455 ± 23 |

| Renal artery occlusion (RAO) (1 h) | 102 ± 5 | 77 ± 8 | 82 ± 6 | 451 ± 20 | 373 ± 31 | 387 ± 25 |

| RAR (3 h) | 103 ± 4 | 86 ± 7 | 91 ± 9 | 455 ± 26 | 385 ± 26 | 396 ± 29 |

| RAR (24 h) | 105 ± 3 | 68 ± 7 | 74 ± 5 | 454 ± 18 | 342 ± 30 | 371 ± 36 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tsao, P.-C.; Lai, C.-C.; Fu, S.-K.; Yu, C.-H.; Chen, J.-H.; Tang, C.-Y. High-Intensity Interval Training Attenuates Inflammation in Cardiorenal Syndrome Induced by Renal Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Life 2026, 16, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010044

Tsao P-C, Lai C-C, Fu S-K, Yu C-H, Chen J-H, Tang C-Y. High-Intensity Interval Training Attenuates Inflammation in Cardiorenal Syndrome Induced by Renal Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Life. 2026; 16(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsao, Po-Chien, Chang-Chi Lai, Szu-Kai Fu, Chia-Hsien Yu, Jing-Hsuan Chen, and Chia-Yu Tang. 2026. "High-Intensity Interval Training Attenuates Inflammation in Cardiorenal Syndrome Induced by Renal Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury in Rats" Life 16, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010044

APA StyleTsao, P.-C., Lai, C.-C., Fu, S.-K., Yu, C.-H., Chen, J.-H., & Tang, C.-Y. (2026). High-Intensity Interval Training Attenuates Inflammation in Cardiorenal Syndrome Induced by Renal Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Life, 16(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010044