Prognostic Significance of Preoperative Neurological Versus Radiological Deterioration in Older Patients with Moderate-to-Mild Traumatic Brain Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

2.2. Neurological and Radiological Monitoring Protocol

2.3. Definition of Preoperative Deterioration

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Outcome Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Outcomes According to Deterioration Type

3.3. Multivariable Analyses for Clinical Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBI | traumatic brain injury |

| GCS | Glasgow Coma Scale |

| CT | computed tomography |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| GOS | Glasgow Outcome Scale |

| CI | confidence interval |

| OR | odds ratio |

| SD | standard deviation |

References

- Ma, Z.; He, Z.; Li, Z.; Gong, R.; Hui, J.; Weng, W.; Wu, X.; Yang, C.; Jiang, J.; Xie, L.; et al. Traumatic brain injury in elderly population: A global systematic review and meta-analysis of in-hospital mortality and risk factors among 2.22 million individuals. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H.J.; McCormick, W.C.; Kagan, S.H. Traumatic brain injury in older adults: Epidemiology, outcomes, and future implications. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 1590–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laic, R.A.G.; Verhamme, P.; Vander Sloten, J.; Depreitere, B. Long-term outcomes after traumatic brain injury in elderly patients on antithrombotic therapy. Acta Neurochir. 2023, 165, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.H.; Yun, J.H.; Kim, S.J.; Chung, J.; Lee, S.K. Anticoagulation and Antiplatelet Agent Resumption Timing following Traumatic Brain Injury. Korean J. Neurotrauma 2023, 19, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haji, K.; Suehiro, E.; Kiyohira, M.; Fujiyama, Y.; Suzuki, M. Effect of Antithrombotic Drugs Reversal on Geriatric Traumatic Brain Injury. No Shinkei Geka. 2020, 48, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xie, J.; Xiao, X.; Li, T.; Li, H.; Bai, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, W. Clinical predictors of prognosis in patients with traumatic brain injury combined with extracranial trauma. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retel Helmrich, I.R.A.; Lingsma, H.F.; Turgeon, A.F.; Yamal, J.M.; Steyerberg, E.W. Prognostic Research in Traumatic Brain Injury: Markers, Modeling, and Methodological Principles. J. Neurotrauma 2021, 38, 2502–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrallah, F.; Bellapart, J.; Walsham, J.; Jacobson, E.; To, X.V.; Manzanero, S.; Brown, N.; Meyer, J.; Stuart, J.; Evans, T.; et al. PREdiction and Diagnosis using Imaging and Clinical biomarkers Trial in Traumatic Brain Injury (PREDICT-TBI) study protocol: An observational, prospective, multicentre cohort study for the prediction of outcome in moderate-to-severe TBI. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellstrøm, T.; Kaufmann, T.; Andelic, N.; Soberg, H.L.; Sigurdardottir, S.; Helseth, E.; Andreassen, O.A.; Westlye, L.T. Predicting Outcome 12 Months after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Patients Admitted to a Neurosurgery Service. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.C.; Dams-O’Connor, K.; Morrissey, M.R.; Manley, G.T. Geriatric Traumatic Brain Injury: Epidemiology, Outcomes, Knowledge Gaps, and Future Directions. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenell, S.; Nyholm, L.; Lewén, A.; Enblad, P. Clinical outcome and prognostic factors in elderly traumatic brain injury patients receiving neurointensive care. Acta Neurochir. 2019, 161, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, J.; de Guise, E.; Gosselin, N.; Feyz, M. Comparison of functional outcome following acute care in young, middle-aged and elderly patients with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2006, 20, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagami, K.; Kurogi, R.; Kurogi, A.; Nishimura, K.; Onozuka, D.; Ren, N.; Kada, A.; Nishimura, A.; Arimura, K.; Ido, K.; et al. The Influence of Age on the Outcomes of Traumatic Brain Injury: Findings from a Japanese Nationwide Survey (J-ASPECT Study-Traumatic Brain Injury). World Neurosurg. 2019, 130, e26–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garza, N.; Toussi, A.; Wilson, M.; Shahlaie, K.; Martin, R. The increasing age of TBI patients at a single level 1 trauma center and the discordance between GCS and CT Rotterdam scores in the elderly. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, P.; Séguin, C.; Lo, B.W.Y.; de Guise, E.; Troquet, J.M.; Marcoux, J. Antithrombotic agents and traumatic brain injury in the elderly population: Hemorrhage patterns and outcomes. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 133, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffeng, S.M.; Foks, K.A.; van den Brand, C.L.; Jellema, K.; Dippel, D.W.J.; Jacobs, B.; van der Naalt, J. Evaluation of Clinical Characteristics and CT Decision Rules in Elderly Patients with Minor Head Injury: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Hawryluk, G.W. Targeting Secondary Hematoma Expansion in Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage—State of the Art. Front. Neurol. 2016, 7, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, A.S.; Gilmore, E.; Choi, H.A.; Mayer, S.A. Time course and predictors of neurological deterioration after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2015, 46, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziai, W.C.; Badihian, S.; Ullman, N.; Thompson, C.B.; Hildreth, M.; Piran, P.; Montano, N.; Vespa, P.; Martin, N.; Zuccarello, M.; et al. Hemorrhage Expansion Rates Before and After Minimally Invasive Surgery for Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Post Hoc Analysis of MISTIE II/III. Stroke Vasc. Interv. Neurol. 2024, 4, e001165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podell, J.; Yang, S.; Miller, S.; Felix, R.; Tripathi, H.; Parikh, G.; Miller, C.; Chen, H.; Kuo, Y.M.; Lin, C.Y.; et al. Rapid prediction of secondary neurologic decline after traumatic brain injury: A data analytic approach. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcock, S.; Batoo, D.; Ande, S.R.; Grierson, R.; Essig, M.; Martin, D.; Trivedi, A.; Sinha, N.; Leeies, M.; Zeiler, F.A.; et al. Early diagnosis of mortality using admission CT perfusion in severe traumatic brain injury patients (ACT-TBI): Protocol for a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e047305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimo, H.; Ito, H.; Suzuki, T.; Araki, A.; Hosoi, T.; Sawabe, M. Reviewing the definition of “elderly”. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2006, 6, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, G.; Jennett, B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: A practical scale. Lancet 1974, 2, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakkel, G.; Kollen, B.; Lindeman, E. Understanding the pattern of functional recovery after stroke: Facts and theories. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2004, 22, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroukian, S.M.; Warner, D.F.; Owusu, C.; Given, C.W. Multimorbidity redefined: Prospective health outcomes and the cumulative effect of co-occurring conditions. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCredie, V.A.; Chavarría, J.; Baker, A.J. How do we identify the crashing traumatic brain injury patient—The intensivist’s view. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2021, 27, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Han, C.; Hu, H.; Sun, H. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting early neurological deterioration in patients with moderate traumatic brain injury: A retrospective analysis. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1512125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, F.D.; Dietz, P.A.; Higgins, D.; Whitaker, T.S. Time to deterioration of the elderly, anticoagulated, minor head injury patient who presents without evidence of neurologic abnormality. J. Trauma. 2003, 54, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marincowitz, C.; Lecky, F.E.; Townend, W.; Borakati, A.; Fabbri, A.; Sheldon, T.A. The Risk of Deterioration in GCS13-15 Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury Identified by Computed Tomography Imaging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Neurotrauma 2018, 35, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmarou, A.; Lu, J.; Butcher, I.; McHugh, G.S.; Murray, G.D.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Mushkudiani, N.A.; Choi, S.; Maas, A.I. Prognostic value of the Glasgow Coma Scale and pupil reactivity in traumatic brain injury assessed pre-hospital and on enrollment: An IMPACT analysis. J. Neurotrauma 2007, 24, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husson, E.C.; Ribbers, G.M.; Willemse-van Son, A.H.; Verhagen, A.P.; Stam, H.J. Prognosis of six-month functioning after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of prospective cohort studies. J. Rehabil. Med. 2010, 42, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depreitere, B.; Becker, C.; Ganau, M.; Gardner, R.C.; Younsi, A.; Lagares, A.; Marklund, N.; Metaxa, V.; Muehlschlegel, S.; Newcombe, V.F.J.; et al. Unique considerations in the assessment and management of traumatic brain injury in older adults. Lancet Neurol. 2025, 24, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karibe, H.; Hayashi, T.; Narisawa, A.; Kameyama, M.; Nakagawa, A.; Tominaga, T. Clinical Characteristics and Outcome in Elderly Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: For Establishment of Management Strategy. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2017, 57, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Kirov, I.I.; Gonen, O.; Ge, Y.; Grossman, R.I.; Lui, Y.W. MR Imaging Applications in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: An Imaging Update. Radiology 2016, 279, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.; Pang, P.S.; Raslan, A.M.; Selden, N.R.; Cetas, J.S. External retrospective validation of Brain Injury Guidelines criteria and modified guidelines for improved care value in the management of patients with low-risk neurotrauma. J. Neurosurg. 2020, 133, 1880–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n = 58) | No Deterioration (n = 24) | Deterioration (n = 34) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 76.4 ± 6.6 | 76.1 ± 6.8 | 76.7 ± 6.5 | 0.750 |

| Male sex | 38 (65.5) | 17 (70.8) | 21 (61.8) | 0.579 |

| Hypertension | 34 (58.6) | 13 (54.2) | 21 (61.8) | 0.598 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (27.6) | 6 (25.0) | 10 (29.4) | 0.773 |

| Cardiac disease | 7 (12.1) | 1 (4.2) | 6 (17.6) | 0.221 |

| Prior stroke | 8 (13.8) | 1 (4.2) | 7 (20.6) | 0.123 |

| Antithrombotic use | 17 (29.3) | 6 (25.0) | 11 (32.4) | 0.575 |

| Initial radiological findings | ||||

| Subdural hemorrhage | 44 (75.9) | 21 (87.5) | 23 (67.6) | 0.121 |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 14 (24.1) | 6 (25.0) | 8 (23.5) | 1.000 |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 23 (39.7) | 6 (25.0) | 17 (50.0) | 0.064 |

| Rotterdam CT score | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | 0.176 |

| High-energy trauma | 8 (13.8) | 4 (16.7) | 4 (11.8) | 0.706 |

| Preoperative initial GCS | 13.0 (11.0–14.8) | 12.0 (10.0–14.0) | 13.0 (12.0–15.0) | 0.220 |

| Surgical procedure | 0.414 | |||

| Craniectomy | 21 (36.2) | 7 (29.2) | 14 (41.2) | |

| Craniotomy | 37 (63.8) | 17 (70.8) | 20 (58.8) | |

| In-hospital death | 14 (24.1) | 2 (8.3) | 12 (35.3) | 0.028 |

| Unfavorable GOS at 6 months | 38 (65.5) | 15 (62.5) | 23 (67.6) | 0.777 |

| Time interval to deterioration, h | 11.9 (5.1–38.0) | |||

| Deterioration ≤ 24 h | 25 (73.5) | |||

| Deterioration ≤ 12 h | 18 (52.9) |

| Outcome | Neurological Deterioration | p-Value | Radiological Deterioration | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 44) | Yes (n = 14) | No (n = 38) | Yes (n = 20) | |||

| In-hospital death | 6 (13.6) | 8 (57.1) | 0.002 | 10 (26.3) | 4 (20.0) | 0.751 |

| Unfavorable GOS | 24 (54.5) | 12 (85.7) | 0.057 | 25 (65.8) | 11 (55.0) | 0.570 |

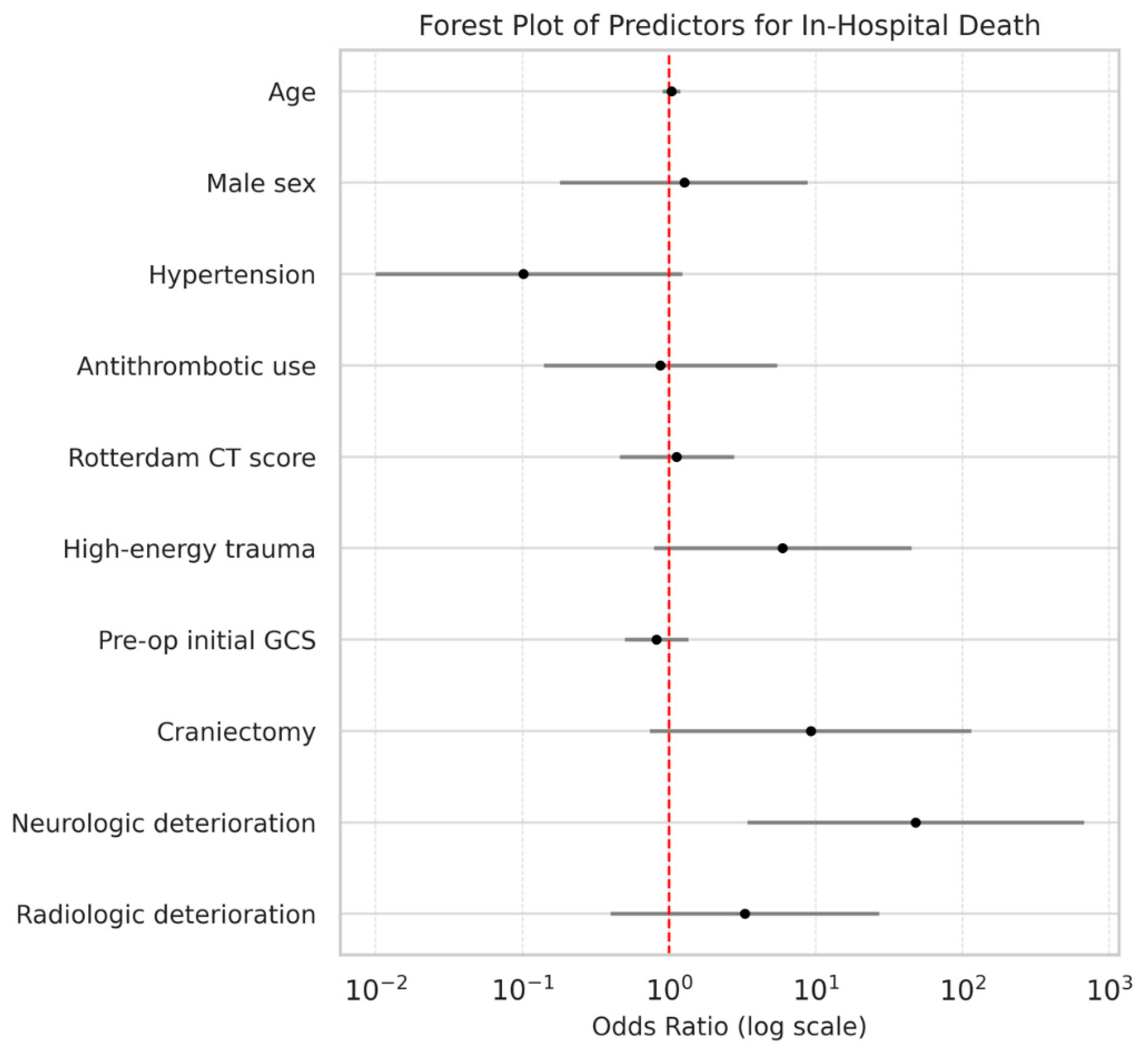

| Outcome | Variable | β | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital death | Age | 0.04 | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 0.623 |

| Male sex | 0.24 | 1.3 (0.2–8.8) | 0.806 | |

| Hypertension | −2.29 | 0.1 (0.0–1.2) | 0.072 | |

| Antithrombotic use | −0.14 | 0.9 (0.1–5.5) | 0.884 | |

| Rotterdam CT score | 0.12 | 1.1 (0.5–2.8) | 0.797 | |

| High-energy trauma | 1.78 | 5.9 (0.8–45.0) | 0.084 | |

| Preoperative initial GCS | −0.20 | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.434 | |

| Craniectomy | 2.22 | 9.2 (0.7–115.0) | 0.084 | |

| Neurological deterioration | 3.87 | 47.9 (3.4–670.9) | 0.004 | |

| Radiological deterioration | 1.19 | 3.3 (0.4–27.1) | 0.269 |

| Outcome | Variable | β | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfavorable GOS | Age | 0.10 | 1.1 (1.0–1.3) | 0.092 |

| Male sex | 1.75 | 5.8 (0.9–36.3) | 0.061 | |

| Hypertension | −0.70 | 0.5 (0.1–2.6) | 0.406 | |

| Antithrombotic use | 0.80 | 2.2 (0.4–12.7) | 0.367 | |

| Rotterdam CT score | 0.20 | 1.2 (0.6–2.5) | 0.591 | |

| High-energy trauma | −0.36 | 0.7 (0.1–4.9) | 0.721 | |

| Preoperative initial GCS | −0.62 | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.013 | |

| Craniectomy | 0.90 | 2.4 (0.4–13.6) | 0.305 | |

| Neurological deterioration | 3.56 | 35.0 (2.0–601.7) | 0.014 | |

| Radiological deterioration | 0.10 | 1.1 (0.2–5.3) | 0.901 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lee, S.H.; Lee, J.T.; Park, Y.-s. Prognostic Significance of Preoperative Neurological Versus Radiological Deterioration in Older Patients with Moderate-to-Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Life 2026, 16, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010028

Lee SH, Lee JT, Park Y-s. Prognostic Significance of Preoperative Neurological Versus Radiological Deterioration in Older Patients with Moderate-to-Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Life. 2026; 16(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Shin Heon, Jong Tae Lee, and Yong-sook Park. 2026. "Prognostic Significance of Preoperative Neurological Versus Radiological Deterioration in Older Patients with Moderate-to-Mild Traumatic Brain Injury" Life 16, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010028

APA StyleLee, S. H., Lee, J. T., & Park, Y.-s. (2026). Prognostic Significance of Preoperative Neurological Versus Radiological Deterioration in Older Patients with Moderate-to-Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Life, 16(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010028