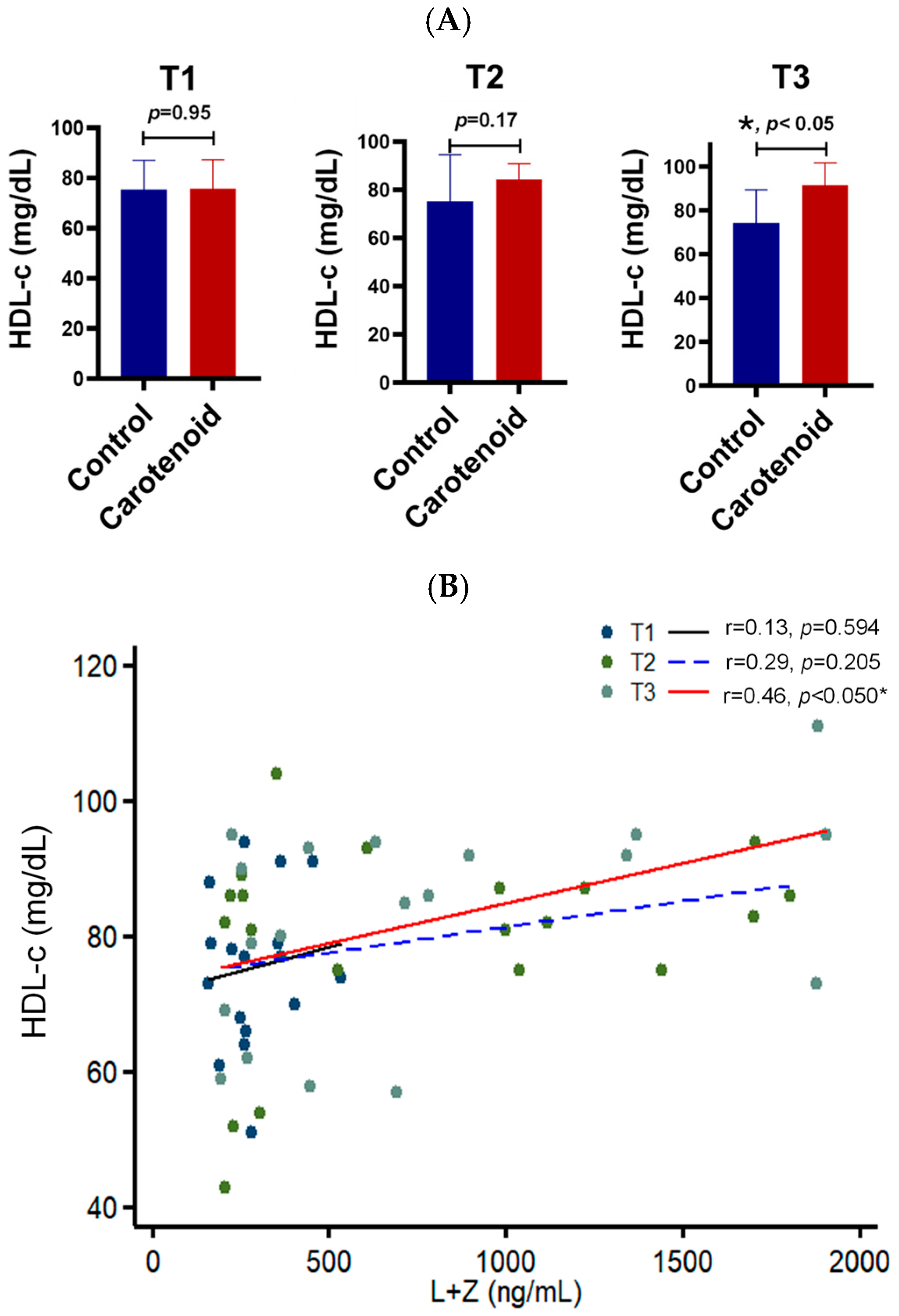

Retinal Carotenoid Supplementation Increases HDL Cholesterol in Humans and Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. L-ZIP Clinical Trial

2.2. Carotenoid Detection by HPLC

2.3. Animal Carotenoid-Feeding Experiments

2.4. Measurement of Serum Lipid Profiles

2.5. Statistical Analysis

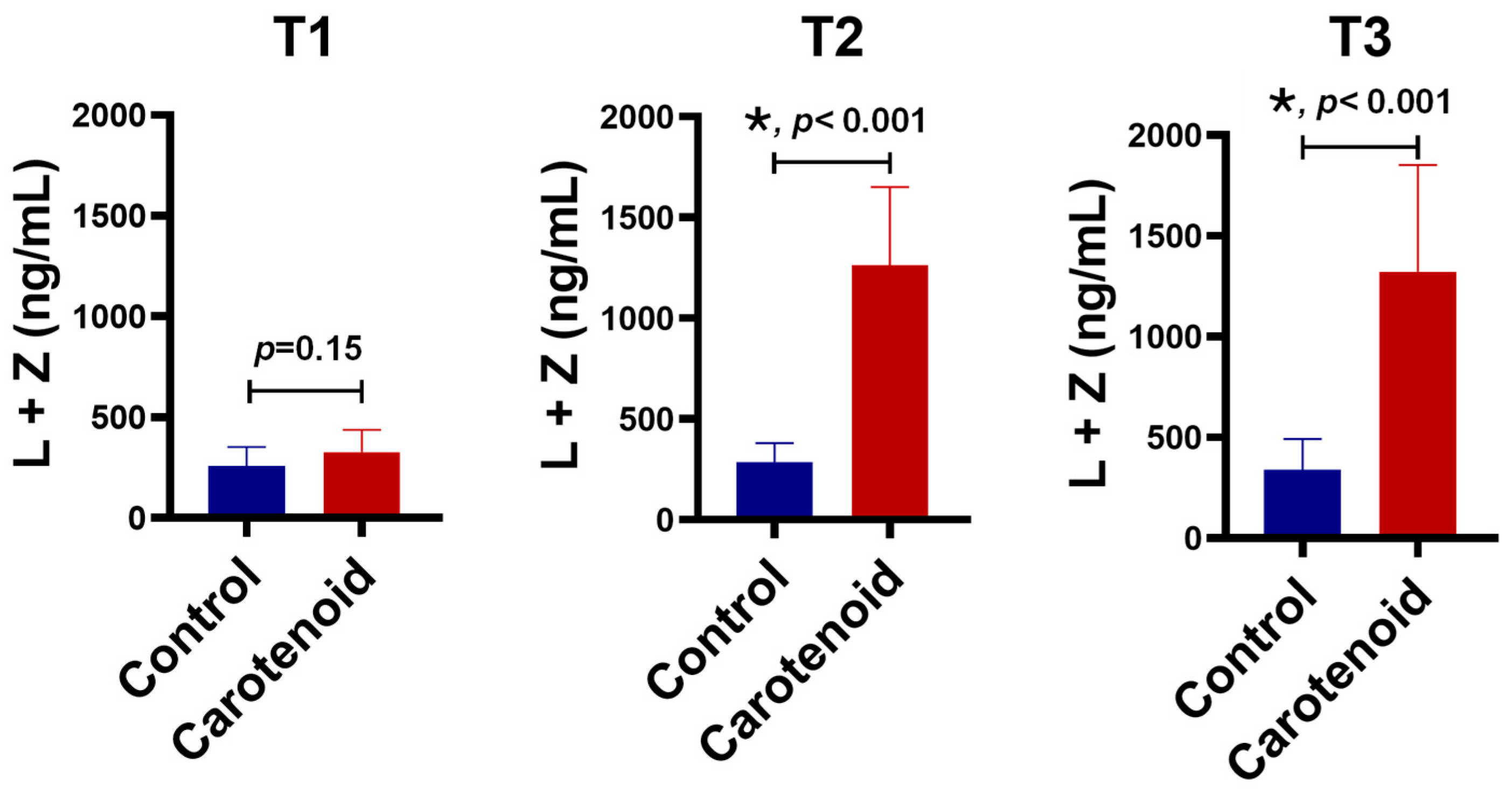

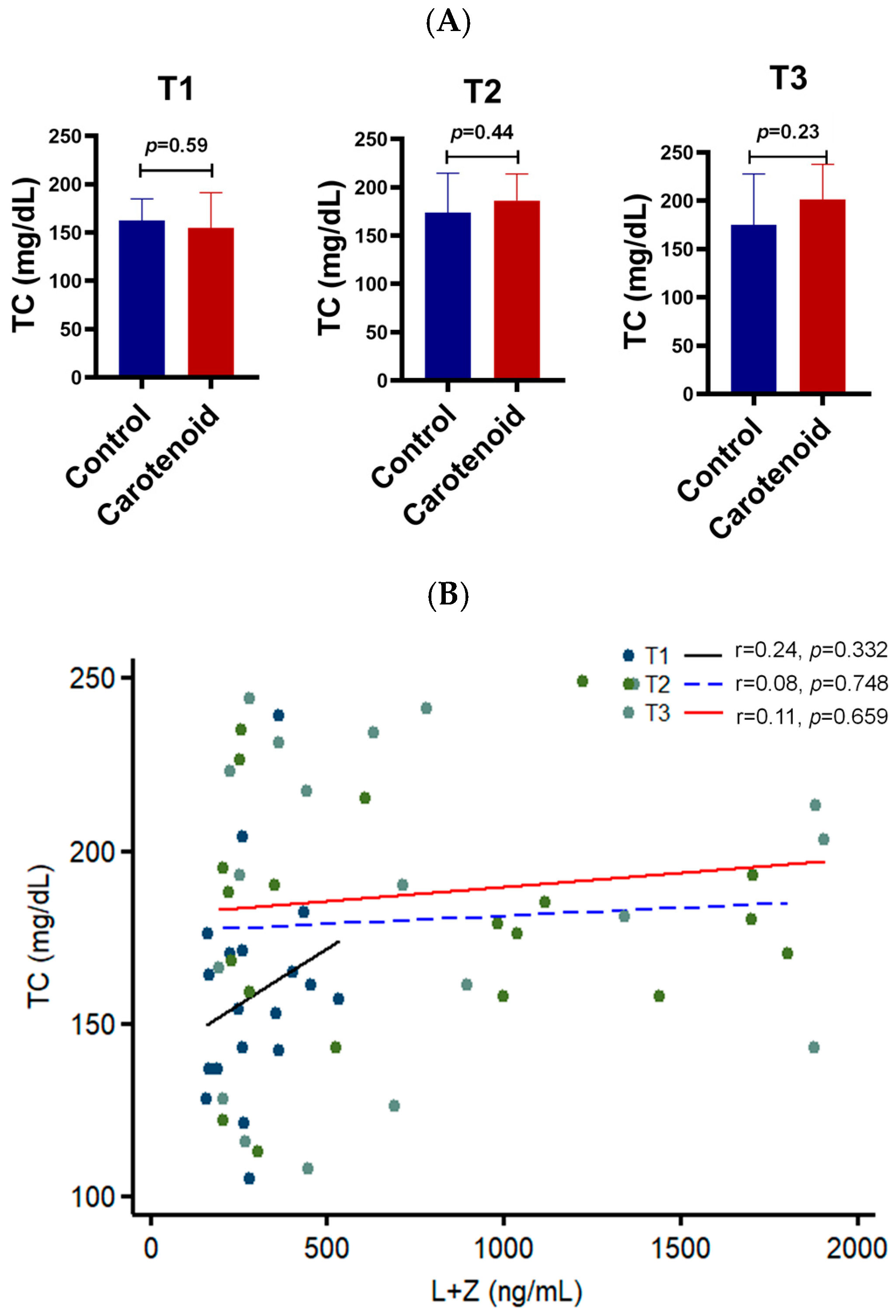

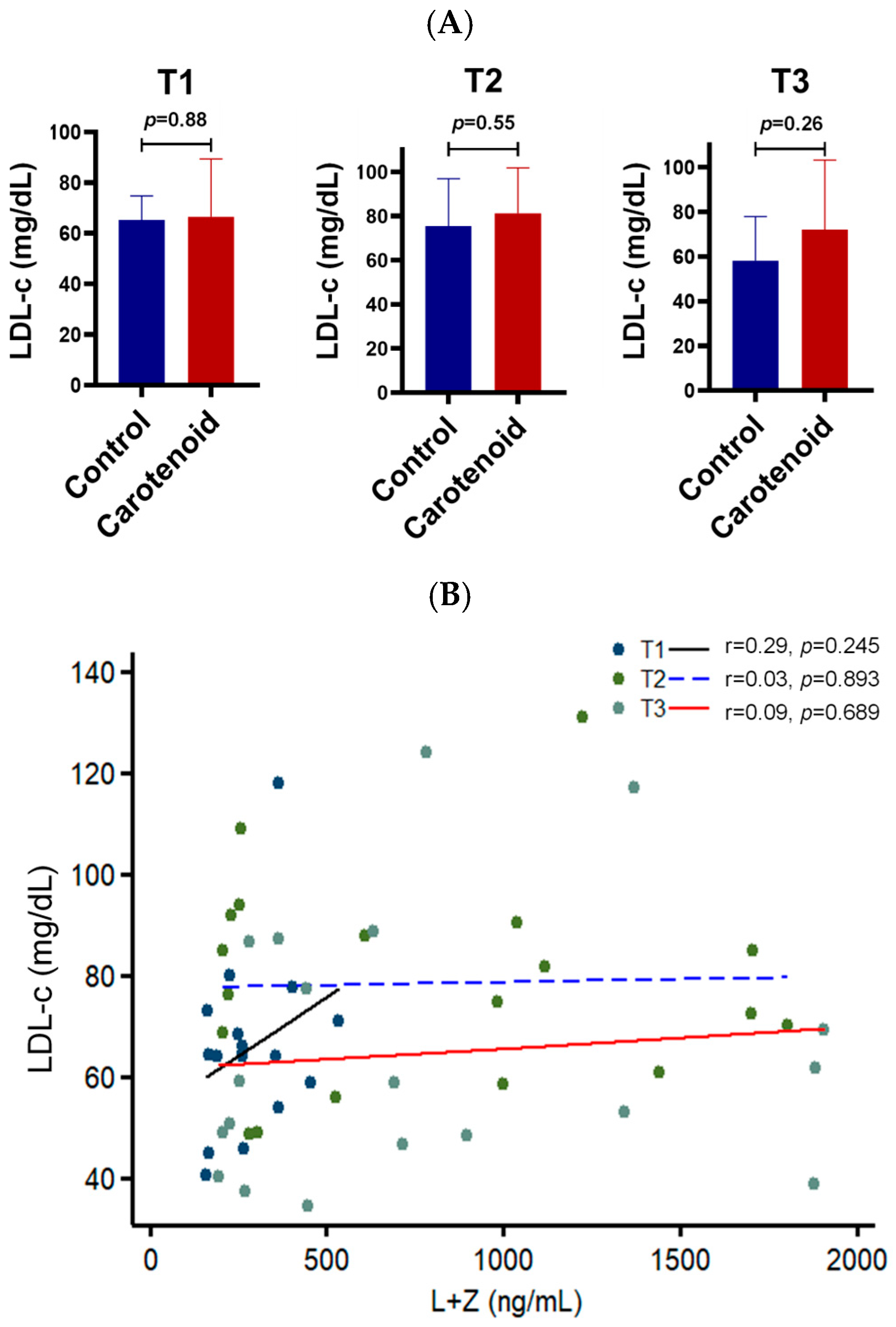

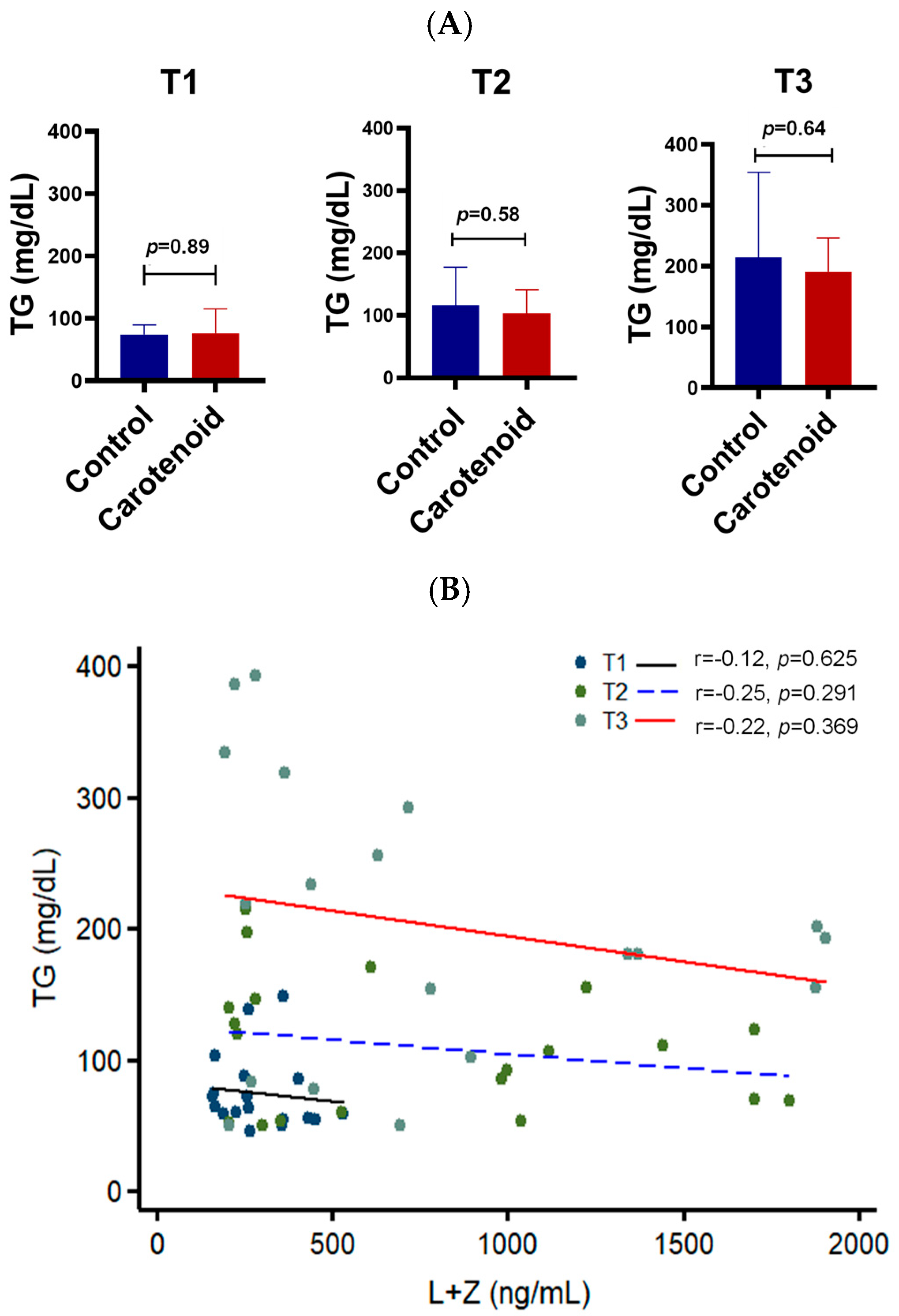

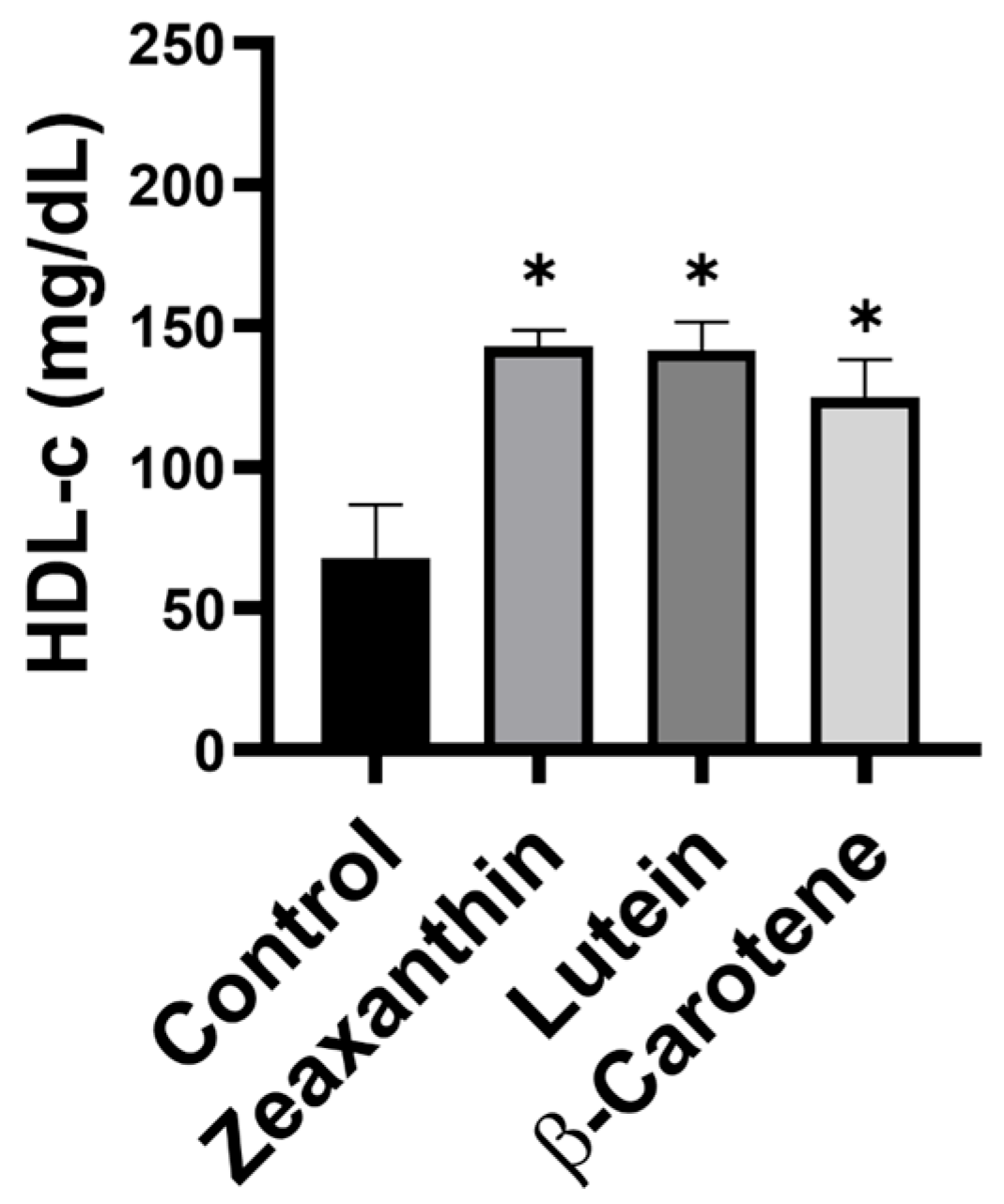

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krinsky, N.I. Antioxidant functions of carotenoids. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1989, 7, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, A.; Skibsted, L.H. Free radical transients in photobleaching of xanthophylls and carotenes. Free. Radic. Res. 1997, 26, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundelin, S.P.; Nilsson, S.E. Lipofuscin-formation in retinal pigment epithelial cells is reduced by antioxidants. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 31, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Lyu, Y.; Srinivasagan, R.; Wu, J.; Ojo, B.; Tang, M.; El-Rassi, G.D.; Metzinger, K.; Smith, B.J.; Lucas, E.A.; et al. Astaxanthin-Shifted Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Inflammation and Metabolic Homeostasis in Mice. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 2687–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krinsky, N.I.; Landrum, J.T.; Bone, R.A. Biologic mechanisms of the protective role of lutein and zeaxanthin in the eye. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2003, 23, 171–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachik, F.; Bernstein, P.S.; Garland, D.L. Identification of lutein and zeaxanthin oxidation products in human and monkey retinas. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997, 38, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar]

- Khachik, F.; de Moura, F.F.; Zhao, D.Y.; Aebischer, C.P.; Bernstein, P.S. Transformations of selected carotenoids in plasma, liver, and ocular tissues of humans and in nonprimate animal models. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 3383–3392. [Google Scholar]

- Krinsky, N.I.; Wang, X.D.; Tang, G.; Russell, R.M. Mechanism of carotenoid cleavage to retinoids. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993, 691, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.H. Mechanisms of Transport and Delivery of Vitamin A and Carotenoids to the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1801046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for age-related macular degeneration and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 1417–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 Research Group. Lutein + zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids for age-related macular degeneration: The Age-Related Eye Disease Study 2 (AREDS2) randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013, 309, 2005–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabour-Pickett, S.; Beatty, S.; Connolly, E.; Loughman, J.; Stack, J.; Howard, A.; Klein, R.; Klein, B.E.; Meuer, S.M.; Myers, C.E.; et al. Supplementation with three different macular carotenoid formulations in patients with early age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2014, 34, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, J.M.; Ajani, U.A.; Sperduto, R.D.; Hiller, R.; Blair, N.; Burton, T.C.; Farber, M.D.; Gragoudas, E.S.; Haller, J.; Miller, D.T.; et al. Dietary carotenoids, vitamins A, C, and E, and advanced age-related macular degeneration. JAMA 1994, 272, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lem, D.W.; Davey, P.G.; Gierhart, D.L.; Rosen, R.B. A Systematic Review of Carotenoids in the Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, B.R., Jr.; Renzi, L.M. Carotenoids. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 474–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, R.; Gorusupudi, A.; Bernstein, P.S. The macular carotenoids: A biochemical overview. Biochim. Biophys Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2020, 1865, 158617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, P.S.; Li, B.; Vachali, P.P.; Gorusupudi, A.; Shyam, R.; Henriksen, B.S.; Nolan, J.M. Lutein, zeaxanthin, and meso-zeaxanthin: The basic and clinical science underlying carotenoid-based nutritional interventions against ocular disease. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2016, 50, 34–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdman, J.W., Jr.; Bierer, T.L.; Gugger, E.T. Absorption and transport of carotenoids. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993, 691, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neale, B.M.; Fagerness, J.; Reynolds, R.; Sobrin, L.; Parker, M.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Tan, P.L.; Oh, E.C.; Merriam, J.E.; Souied, E.; et al. Genome-wide association study of advanced age-related macular degeneration identifies a role of the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 7395–7400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritsche, L.G.; Igl, W.; Bailey, J.N.; Grassmann, F.; Sengupta, S.; Bragg-Gresham, J.L.; Burdon, K.P.; Hebbring, S.J.; Wen, C.; Gorski, M.; et al. A large genome-wide association study of age-related macular degeneration highlights contributions of rare and common variants. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, G.P.; Hessel, S.; Eichinger, A.; Noy, N.; Moise, A.R.; Wyss, A.; Palczewski, K.; von Lintig, J. ISX is a retinoic acid-sensitive gatekeeper that controls intestinal beta,beta-carotene absorption and vitamin A production. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2010, 24, 1656–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Vachali, P.; Chang, F.Y.; Gorusupudi, A.; Arunkumar, R.; Shi, L.; Rognon, G.T.; Frederick, J.M.; Bernstein, P.S. HDL is the primary transporter for carotenoids from liver to retinal pigment epithelium in transgenic ApoA-I(-/-)/Bco2(-/-) mice. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 716, 109111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulinet, S.; Chapman, M.J. Plasma LDL and HDL subspecies are heterogenous in particle content of tocopherols and oxygenated and hydrocarbon carotenoids: Relevance to oxidative resistance and atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997, 17, 786–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.J.; Hammond, B.R.; Yeum, K.J.; Qin, J.; Wang, X.D.; Castaneda, C.; Snodderly, D.M.; Russell, R.M. Relation among serum and tissue concentrations of lutein and zeaxanthin and macular pigment density. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loane, E.; Nolan, J.M.; O’Donovan, O.; Bhosale, P.; Bernstein, P.S.; Beatty, S. Transport and retinal capture of lutein and zeaxanthin with reference to age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2008, 53, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Vachali, P.; Bernstein, P.S. Human ocular carotenoid-binding proteins. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2010, 9, 1418–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risk factors for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. The Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1992, 110, 1701–1708. [CrossRef]

- Abalain, J.H.; Carre, J.L.; Leglise, D.; Robinet, A.; Legall, F.; Meskar, A.; Floch, H.H.; Colin, J. Is age-related macular degeneration associated with serum lipoprotein and lipoparticle levels? Clin. Chim. Acta 2002, 326, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.S.; Mitchell, P.; Smith, W.; Wang, J.J. Cardiovascular risk factors and the long-term incidence of age-related macular degeneration: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2007, 114, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addo, E.K.; Gorusupudi, A.; Allman, S.; Bernstein, P.S. The Lutein and Zeaxanthin in Pregnancy (L-ZIP) study-carotenoid supplementation during pregnancy: Ocular and systemic effects-study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Dang, K.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y. Dietary carotenoid intakes and biological aging among US adults, NHANES 1999-2018. Nutr. J. 2025, 24, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksen, B.S.; Chan, G.; Hoffman, R.O.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Ermakov, I.V.; Gellermann, W.; Bernstein, P.S. Interrelationships between maternal carotenoid status and newborn infant macular pigment optical density and carotenoid status. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 5568–5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorusupudi, A.; Rallabandi, R.; Li, B.; Arunkumar, R.; Blount, J.D.; Rognon, G.T.; Chang, F.Y.; Wade, A.; Lucas, S.; Conboy, J.C.; et al. Retinal bioavailability and functional effects of a synthetic very-long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2017739118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Vachali, P.P.; Gorusupudi, A.; Shen, Z.; Sharifzadeh, H.; Besch, B.M.; Nelson, K.; Horvath, M.M.; Frederick, J.M.; Baehr, W.; et al. Inactivity of human beta,beta-carotene-9’,10’-dioxygenase (BCO2) underlies retinal accumulation of the human macular carotenoid pigment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10173–10178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storti, F.; Klee, K.; Todorova, V.; Steiner, R.; Othman, A.; van der Velde-Visser, S.; Samardzija, M.; Meneau, I.; Barben, M.; Karademir, D.; et al. Impaired ABCA1/ABCG1-mediated lipid efflux in the mouse retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) leads to retinal degeneration. eLife 2019, 8, e45100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amengual, J.; Lobo, G.P.; Golczak, M.; Li, H.N.; Klimova, T.; Hoppel, C.L.; Wyss, A.; Palczewski, K.; von Lintig, J. A mitochondrial enzyme degrades carotenoids and protects against oxidative stress. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2011, 25, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontush, A. HDL and Reverse Remnant-Cholesterol Transport (RRT): Relevance to Cardiovascular Disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 1086–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliesler, S.J. Cholesterol homeostasis in the retina: Seeing is believing. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, W.E.; Duell, P.B.; Kean, R.; Wang, Y. The prime role of HDL to transport lutein into the retina: Evidence from HDL-deficient WHAM chicks having a mutant ABCA1 transporter. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 4226–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, R.; Gorusupudi, A.; Li, B.; Blount, J.D.; Nwagbo, U.; Kim, H.J.; Sparrow, J.R.; Bernstein, P.S. Lutein and zeaxanthin reduce A2E and iso-A2E levels and improve visual performance in Abca4(-/-)/Bco2(-/-) double knockout mice. Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 209, 108680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Ahmed, F.; Bernstein, P.S. Studies on the singlet oxygen scavenging mechanism of human macular pigment. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 504, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landrum, J.T.; Bone, R.A. Lutein, zeaxanthin, and the macular pigment. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 385, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, B.; Addo, E.K.; Chang, F.-Y.; Guo, S.; Awuni, M.; Conway, E.; Ying, J.; Ramos, D.; Bernstein, P.S. Retinal Carotenoid Supplementation Increases HDL Cholesterol in Humans and Mice. Life 2026, 16, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010023

Li B, Addo EK, Chang F-Y, Guo S, Awuni M, Conway E, Ying J, Ramos D, Bernstein PS. Retinal Carotenoid Supplementation Increases HDL Cholesterol in Humans and Mice. Life. 2026; 16(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Binxing, Emmanuel K. Addo, Fu-Yen Chang, Shukui Guo, Moses Awuni, Emily Conway, Jialai Ying, Dylan Ramos, and Paul S. Bernstein. 2026. "Retinal Carotenoid Supplementation Increases HDL Cholesterol in Humans and Mice" Life 16, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010023

APA StyleLi, B., Addo, E. K., Chang, F.-Y., Guo, S., Awuni, M., Conway, E., Ying, J., Ramos, D., & Bernstein, P. S. (2026). Retinal Carotenoid Supplementation Increases HDL Cholesterol in Humans and Mice. Life, 16(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010023