Trends in the Management of Bladder Cancer with Emphasis on Frailty: A Nationwide Analysis of More Than 49,000 Patients from a German Hospital Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Assessment of Frailty

2.3. Sex, Age and Comorbidities

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Trends in Treatments and Outcomes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Padala, S.A.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Rumgay, H.; Li, M.; Yu, H.; Pan, H.; Ni, J. The global landscape of bladder cancer incidence and mortality in 2020 and projections to 2040. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 04109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontero, P.; Birtle, A.; Capoun, O.; Compérat, E.; Dominguez-Escrig, J.L.; Liedberg, F.; Mariappan, P.; Masson-Lecomte, A.; Mostafid, H.A.; Pradere, B.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer (TaT1 and Carcinoma In Situ)—A Summary of the 2024 Guidelines Update. Eur. Urol. 2024, 86, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, A.G.; Bruins, H.M.; Carrion, A.; Cathomas, R.; Compérat, E.; Dimitropoulos, K.; Efstathiou, J.A.; Fietkau, R.; Kailavasan, M.; Lorch, A.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2025 Guidelines. Eur. Urol. 2025, 87, 582–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakula, M.; Hudolin, T.; Knezevic, N.; Zimak, Z.; Andelic, J.; Juric, I.; Gamulin, M.; Gnjidic, M.; Kastelan, Z. Intravesical Gemcitabine and Docetaxel Therapy for BCG-Naïve Patients: A Promising Approach to Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer. Life 2024, 14, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daha, C.; Brătucu, E.; Burlănescu, I.; Prunoiu, V.M.; Moisă, H.A.; Neicu, Ș.A.; Simion, L. Severe Rectal Stenosis as the First Clinical Appearance of a Metastasis Originating from the Bladder: A Case Report and Literature Review. Life 2025, 15, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarelli, V.; Rosati, D.; Canale, V.; Salciccia, S.; Di Lascio, G.; Bevilacqua, G.; Tufano, A.; Sciarra, A.; Cantisani, V.; Franco, G.; et al. The Current Role of Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the Diagnosis and Staging of Bladder Cancer: A Review of the Available Literature. Life 2024, 14, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scilipoti, P.; Moschini, M.; Li, R.; Lerner, S.P.; Black, P.C.; Necchi, A.; Rouprêt, M.; Shariat, S.F.; Gupta, S.; Morgans, A.K.; et al. The Financial Burden of Localized and Metastatic Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2025, 87, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimberg, D.C.; Shah, A.; Molinger, J.; Whittle, J.; Gupta, R.T.; Wischmeyer, P.E.; McDonald, S.R.; Inman, B.A. Assessments of frailty in bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2020, 38, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R.A.; Hemal, A.K. Frailty and sarcopenia impact surgical and oncologic outcomes after radical cystectomy in patients with bladder cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2018, 7, S763–S764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handforth, C.; Clegg, A.; Young, C.; Simpkins, S.; Seymour, M.T.; Selby, P.J.; Young, J. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1091–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, T.; Neuburger, J.; Kraindler, J.; Keeble, E.; Smith, P.; Ariti, C.; Arora, S.; Street, A.; Parker, S.; Roberts, H.C.; et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: An observational study. Lancet 2018, 391, 1775–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dengler, J.; Gheewala, H.; Kraft, C.N.; Hegewald, A.A.; Dörre, R.; Heese, O.; Gerlach, R.; Rosahl, S.; Maier, B.; Burger, R.; et al. Changes in frailty among patients hospitalized for spine pathologies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany-a nationwide observational study. Eur. Spine J. 2024, 33, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Allam, A.; Heese, O.; Gerlach, R.; Gheewala, H.; Rosahl, S.K.; Stoffel, M.; Ryang, Y.M.; Burger, R.; Carl, B.; et al. Trends in frailty in brain tumor care during the COVID-19 pandemic in a nationwide hospital network in Germany. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2023, 14, 1383–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Reis, P.F.; de França, P.S.; Dos Santos, M.P.; Martucci, R.B. Influence of nutritional status and frailty phenotype on health-related quality of life of patients with bladder or kidney cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 5139–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamura, H.; Hatakeyama, S.; Momota, M.; Kojima, Y.; Narita, T.; Okamoto, T.; Fujita, N.; Hamano, I.; Togashi, K.; Hamaya, T.; et al. Relationship of frailty with treatment modality selection in patients with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (FRART-BC study). Transl. Androl. Urol. 2021, 10, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornaghi, P.I.; Afferi, L.; Antonelli, A.; Cerruto, M.A.; Mordasini, L.; Mattei, A.; Baumeister, P.; Marra, G.; Krajewski, W.; Mari, A.; et al. Frailty impact on postoperative complications and early mortality rates in patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: A systematic review. Arab. J. Urol. 2020, 19, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlach, R.; Dengler, J.; Bollmann, A.; Stoffel, M.; Youssef, F.; Carl, B.; Rosahl, S.; Ryang, Y.M.; Terzis, J.; Kristof, R.; et al. Neurosurgical care for patients with high-grade gliomas during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: Analysis of routine billing data of a German nationwide hospital network. Neurooncol. Pract. 2023, 10, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutrani, H.; Briggs, J.; Prytherch, D.; Spice, C. Using the Hospital Frailty Risk Score to predict length of stay across all adult ages. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, A.; Maynou, L.; Blodgett, J.M.; Conroy, S. Association between Hospital Frailty Risk Score and length of hospital stay, hospital mortality, and hospital costs for all adults in England: A nationally representative, retrospective, observational cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2025, 6, 100740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elixhauser, A.; Steiner, C.; Harris, D.R.; Coffey, R.M. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med. Care 1998, 36, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, H.B.; Sura, S.D.; Adhikari, D.; Andersen, C.R.; Williams, S.B.; Senagore, A.J.; Kuo, Y.F.; Goodwin, J.S. Adapting the Elixhauser comorbidity index for cancer patients. Cancer 2018, 124, 2018–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baayen, R.H.; Davidson, D.J.; Bates, D.M. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. J. Mem. Lang. 2008, 59, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, N.; Sharma, P. Frailty as a prognostic indicator in the radical cystectomy population: A review. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2019, 51, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BrintzenhofeSzoc, K.; Krok-Schoen, J.I.; Pisegna, J.L.; MacKenzie, A.R.; Canin, B.; Plotkin, E.; Boehmer, L.M.; Shahrokni, A. Survey of cancer care providers’ attitude toward care for older adults with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cary, C.; Tong, Y.; Linsell, S.; Ghani, K.; Miller, D.C.; Weiner, M.; Koch, M.O.; Perkins, S.M.; Zimet, G. Ranking Important Factors for Using Postoperative Chemotherapy in Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: Conjoint Analysis Results from the Michigan Urological Surgery Improvement Collaborative (MUSIC). J. Urol. 2022, 207, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estevez, A.; Kaul, S.; Fleishman, A.; Korets, R.; Chang, P.; Wagner, A.; Bellmunt, J.; Olumi, A.F.; Rayala, H.; Gershman, B. Disparities in the prevalence and management of high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. 2023, 41, 255.e215–255.e221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, R.J.; Oosterlinck, W.; Holmang, S.; Sydes, M.R.; Birtle, A.; Gudjonsson, S.; De Nunzio, C.; Okamura, K.; Kaasinen, E.; Solsona, E.; et al. Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis of Randomized Trials Comparing a Single Immediate Instillation of Chemotherapy After Transurethral Resection with Transurethral Resection Alone in Patients with Stage pTa-pT1 Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: Which Patients Benefit from the Instillation? Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catto, J.W.F.; Khetrapal, P.; Ricciardi, F.; Ambler, G.; Williams, N.R.; Al-Hammouri, T.; Khan, M.S.; Thurairaja, R.; Nair, R.; Feber, A.; et al. Effect of Robot-Assisted Radical Cystectomy with Intracorporeal Urinary Diversion vs. Open Radical Cystectomy on 90-Day Morbidity and Mortality Among Patients with Bladder Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 327, 2092–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khetrapal, P.; Wong, J.K.L.; Tan, W.P.; Rupasinghe, T.; Tan, W.S.; Williams, S.B.; Boorjian, S.A.; Wijburg, C.; Parekh, D.J.; Wiklund, P.; et al. Robot-assisted Radical Cystectomy Versus Open Radical Cystectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Perioperative, Oncological, and Quality of Life Outcomes Using Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flegar, L.; Kraywinkel, K.; Zacharis, A.; Aksoy, C.; Koch, R.; Eisenmenger, N.; Groeben, C.; Huber, J. Treatment trends for muscle-invasive bladder cancer in Germany from 2006 to 2019. World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 1715–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippou, P.; Hugar, L.A.; Louwers, R.; Pomper, A.; Chisolm, S.; Smith, A.B.; Gore, J.L.; Gilbert, S.M. Palliative care knowledge, attitudes, and experiences amongst patients with bladder cancer and their caregivers. Urol. Oncol. 2023, 41, 108.e101–108.e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, S.E.; Quiben, M.; Hazuda, H.P. Distinguishing Comorbidity, Disability, and Frailty. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2018, 7, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2016–2019 | 2020–2022 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 27,979 | 21,160 | |

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 71.9 ± 11.0 | 72.4 ± 10.6 | <0.01 |

| ≤44 years | 1.3% (367) | 1.1% (228) | 0.02 |

| 45−54 years | 5.4% (1507) | 3.8% (809) | <0.01 |

| 55−64 years | 18.0% (5045) | 18.7% (3953) | 0.07 |

| 65−74 years | 27.7% (7747) | 30.2% (6380) | <0.01 |

| 75−84 years | 37.1% (10,394) | 34.9% (7378) | <0.01 |

| ≥85 years | 10.4% (2919) | 11.4% (2412) | <0.01 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 77.3% (21,613) | 77.5% (16,403) | |

| Female | 22.7% (6364) | 22.5% (4757) | 0.49 |

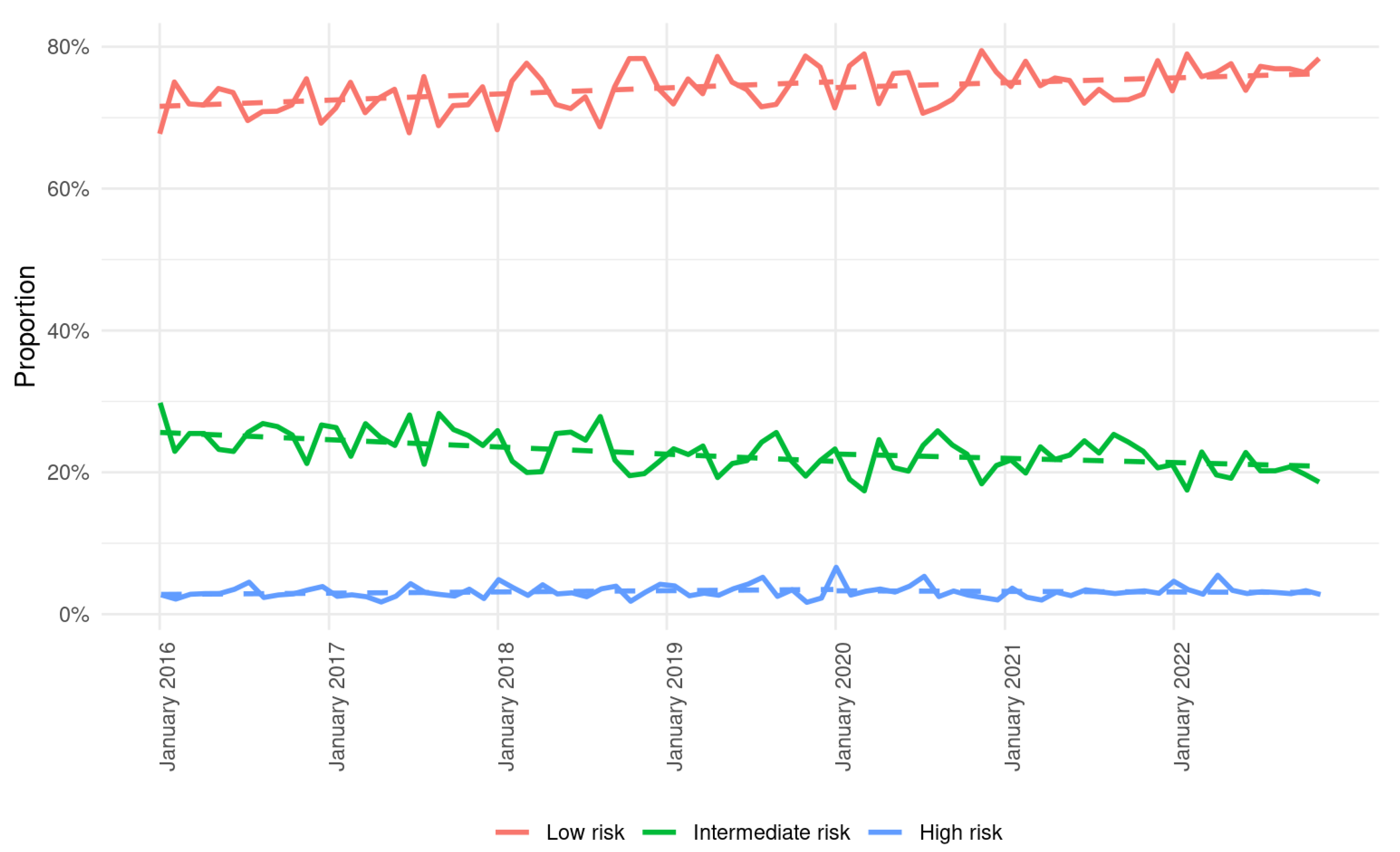

| Hospital Frailty Risk Score | |||

| Low risk | 73.4% (20,549) | 75.5% (15,973) | <0.01 |

| Intermediate risk | 23.5% (6589) | 21.5% (4548) | <0.01 |

| High risk | 3.0% (841) | 3.0% (639) | 0.95 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index | |||

| Mean (SD) | 12.7 ± 9.8 | 12.0 ± 9.3 | <0.01 |

| 0 | 0.0% (12) | 0.0% (7) | 0.75 |

| 1–4 | 7.8% (2195) | 7.6% (1617) | 0.41 |

| ≥5 | 91.7% (25,661) | 91.9% (19,441) | 0.53 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Congestive heart failure | 9.9% (2769) | 9.1% (1934) | <0.01 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 16.2% (4535) | 15.3% (3227) | <0.01 |

| Heart valve diseases | 4.2% (1175) | 3.8% (800) | 0.02 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 10.8% (3027) | 9.4% (1991) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 57.1% (15,976) | 55.0% (11,641) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 6.7% (1882) | 9.6% (2032) | <0.01 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 9.2% (2581) | 9.0% (1910) | 0.46 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 15.1% (4221) | 15.9% (3365) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 8.3% (2323) | 8.3% (1756) | 1 |

| Hypothyroidism | 8.1% (2274) | 9.2% (1951) | <0.01 |

| Renal failure | 31.7% (8865) | 28.7% (6068) | <0.01 |

| Obesity | 12.5% (3486) | 10.8% (2293) | <0.01 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 9.8% (2740) | 9.0% (1901) | <0.01 |

| Depression | 3.0% (833) | 3.1% (665) | 0.3 |

| Metastatic disease | 12.7% (3563) | 11.8% (2497) | <0.01 |

| 2016–2019 | 2020–2022 | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radical cystectomy | 5.6% (1556) | 5.9% (1257) | 1.06 (0.98–1.15) | 0.12 |

| Robotic surgery * | 0.1% (18) | 1.5% (191) | 15.3 (9.38–25.0) | <0.001 |

| Transurethral resection | 72.9% (20,383) | 70.8% (14,980) | 0.89 (0.85–0.92) | <0.001 |

| Early instillation of chemotherapy † | 19.9% (4062) | 17.3% (2595) | 0.90 (0.85–0.95) | <0.001 |

| Systemic therapy | 9.7% (2713) | 10.4% (2202) | 1.10 (1.03–1.17) | 0.003 |

| Best supportive care | 0.7% (198) | 1.3% (265) | 1.93 (1.58–2.35) | <0.001 |

| Insertion of nephrostomy | 10.9% (3052) | 9.5% (2020) | 0.92 (0.86–0.98) | 0.01 |

| Admission to intensive care | 7.7% (2162) | 7.3% (1552) | 0.96 (0.89–1.03) | 0.23 |

| In-hospital mortality | 2.3% (648) | 2.6% (537) | 1.12 (0.99–1.26) | 0.06 |

| Length of stay Mean (SD) Median (IQR) | 5.1 (6.8) 3.0 (2–5) | 4.5 (6.1) 2.0 (2–4) | - - | <0.01 |

| Age | Frailty Group | 2016–2019 | 2020–2022 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Low, % (n) | 10.2% (2101) | 11.2% (1795) | 0.002 |

| Intermediate, % (n) | 8.9% (585) | 8.4% (382) | 0.40 | |

| High, % (n) | 3.2% (27) | 3.9% (25) | 0.56 | |

| Non-elderly (<65 years) | Low, % (n) | 15.5% (885) | 16.7% (688) | 0.11 |

| Intermediate, % (n) | 15.6% (175) | 18.6% (149) | 0.09 | |

| High, % (n) | 3.9% (3) | 12.3% (9) | 0.11 | |

| Elderly (≥65 years) | Low, % (n) | 8.2% (1216) | 9.3% (1107) | 0.001 |

| Intermediate, % (n) | 7.5% (410) | 6.2% (233) | 0.02 | |

| High, % (n) | 3.1% (24) | 2.8% (16) | 0.87 |

| Age | Frailty Group | 2016–2019 | 2020–2022 | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Low, % (n) | 21.1% (3405) | 17.9% (2198) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate, % (n) | 15.9% (621) | 15.5% (388) | 0.72 | |

| High, % (n) | 10.8% (37) | 4.0 (9) | 0.006 | |

| Non-elderly (<65 years) | Low, % (n) | 24.6% (1034) | 20.2% (601) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate, % (n) | 18.5% (94) | 19.3% (58) | 0.006 | |

| High, % (n) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 1 | |

| Elderly (≥65 years) | Low, % (n) | 19.9% (2370) | 17.2% (1597) | <0.001 |

| Intermediate, % (n) | 15.5% (527) | 15.0% (330) | 0.65 | |

| High, % (n) | 11.3% (37) | 4.3% (9) | 0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Klatte, T.; Bold, F.; Dengler, J.; de Martino, M.; Hohenstein, S.; Kuhlen, R.; Bollmann, A.; Steiner, T.; Dengler, N.F. Trends in the Management of Bladder Cancer with Emphasis on Frailty: A Nationwide Analysis of More Than 49,000 Patients from a German Hospital Network. Life 2026, 16, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010169

Klatte T, Bold F, Dengler J, de Martino M, Hohenstein S, Kuhlen R, Bollmann A, Steiner T, Dengler NF. Trends in the Management of Bladder Cancer with Emphasis on Frailty: A Nationwide Analysis of More Than 49,000 Patients from a German Hospital Network. Life. 2026; 16(1):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010169

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlatte, Tobias, Frederic Bold, Julius Dengler, Michela de Martino, Sven Hohenstein, Ralf Kuhlen, Andreas Bollmann, Thomas Steiner, and Nora F. Dengler. 2026. "Trends in the Management of Bladder Cancer with Emphasis on Frailty: A Nationwide Analysis of More Than 49,000 Patients from a German Hospital Network" Life 16, no. 1: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010169

APA StyleKlatte, T., Bold, F., Dengler, J., de Martino, M., Hohenstein, S., Kuhlen, R., Bollmann, A., Steiner, T., & Dengler, N. F. (2026). Trends in the Management of Bladder Cancer with Emphasis on Frailty: A Nationwide Analysis of More Than 49,000 Patients from a German Hospital Network. Life, 16(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010169