Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Glial Activation After Unilateral Cortical Injury in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Focal Cortical Aspiration Model

2.3. Perfusion and Tissue Preparation

2.4. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Protocol

2.5. Data Acquisition and Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. CD11b Expression Reveals Early, Sharply Lateralized Microglial/Macrophage Activation That Resolves by Day 21

3.2. IBA-1 Reveals Delayed Lateralization and Sustained Microglial Reactivity Through Day 21

3.3. GFAP Expression Indicates Gradual, Prolonged Astrocytic GFAP Response That Extends Beyond Microglial Resolution

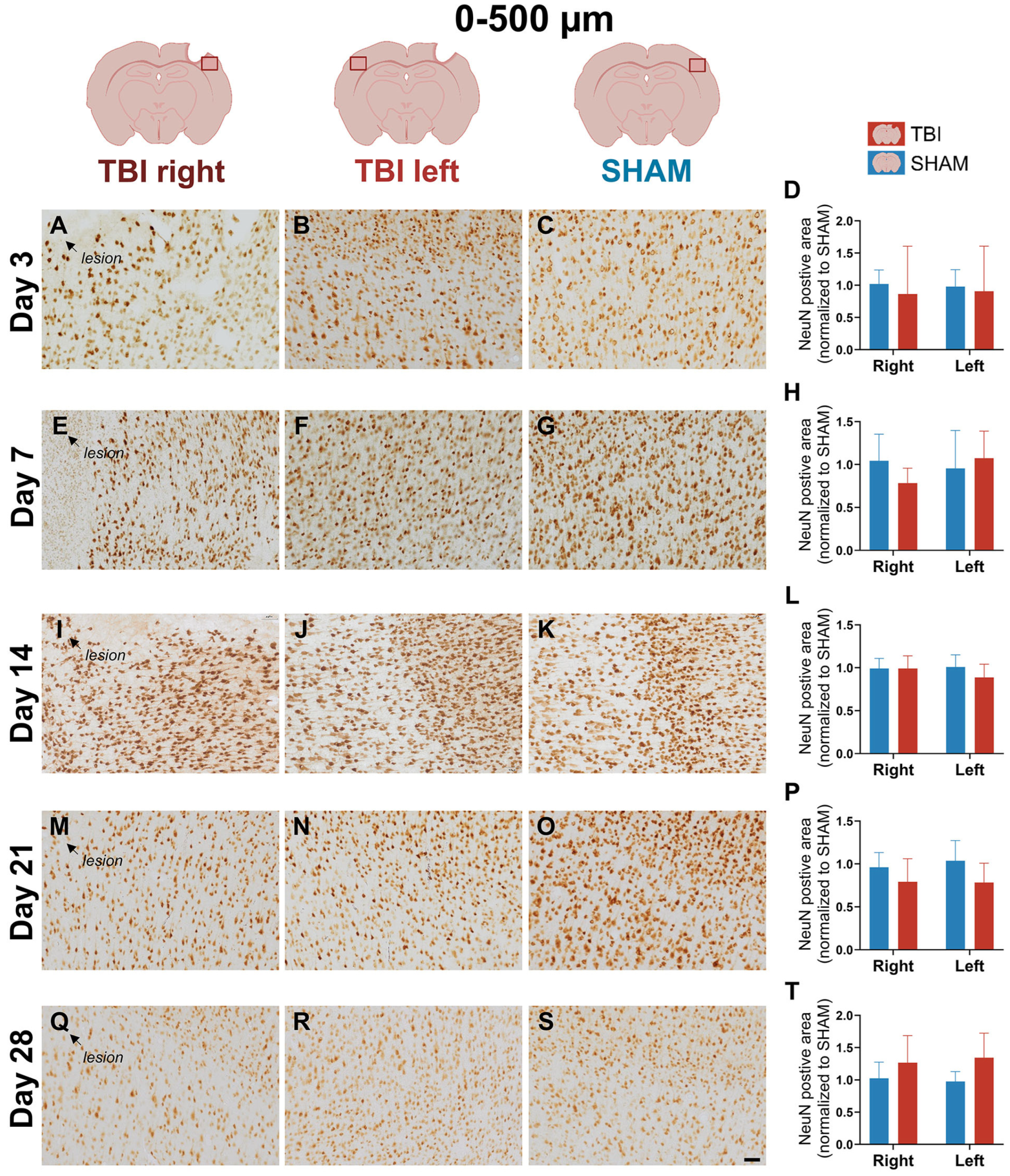

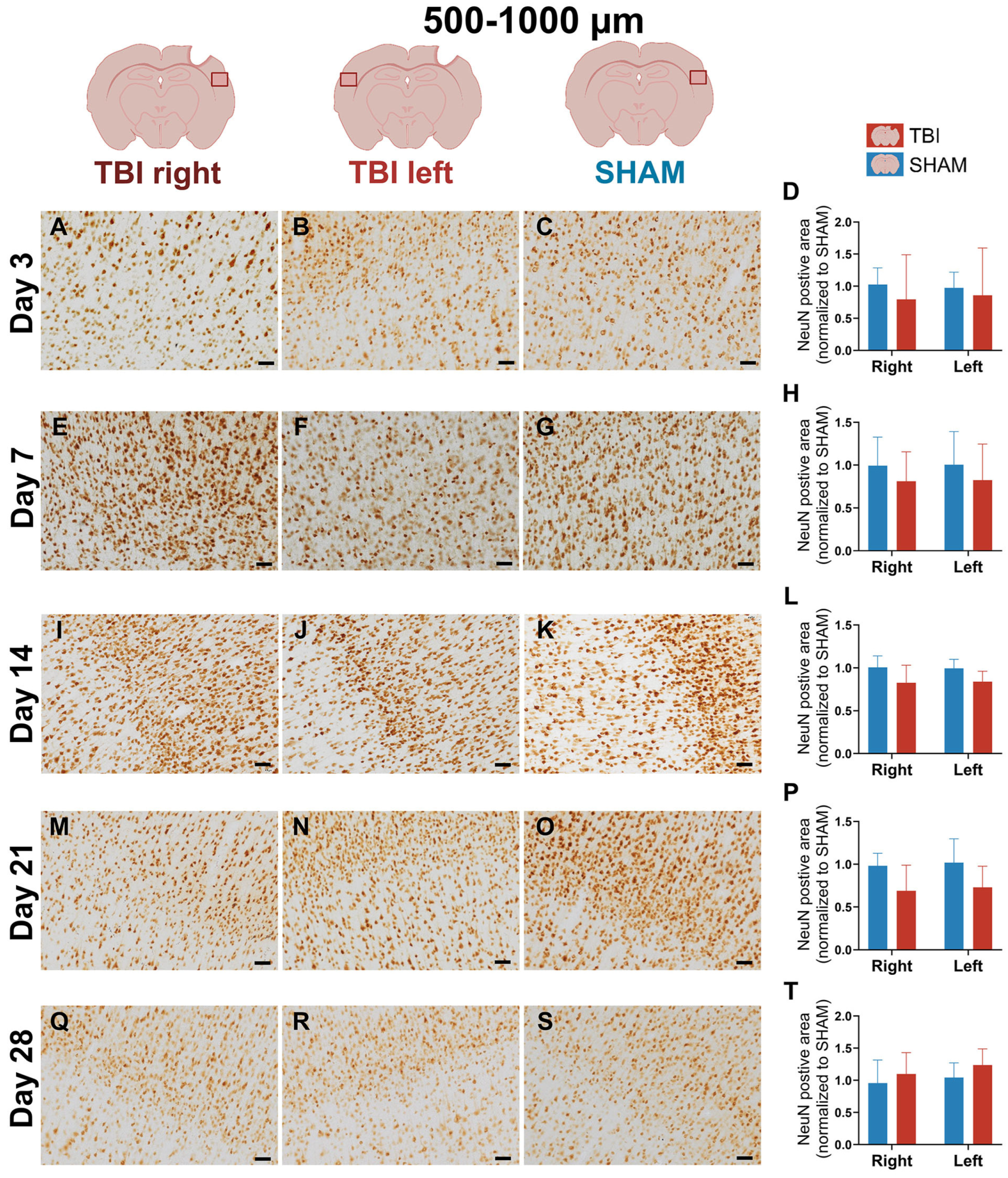

3.4. Stable NeuN Immunoreactivity After Focal TBI

4. Discussion

4.1. Sequential Glial Responses in Focal Cortical Injury

4.1.1. Early, Localized, and Transient CD11b+ Myeloid Activation in the Ipsilateral Cortex Following Focal Injury

4.1.2. Early Bilateral and Sustained IBA-1+ Microglial Response Suggests Interhemispheric Involvement After Focal TBI

4.1.3. Delayed and Bilateral GFAP+ Astrogliosis Reflects Subacute-Chronic Glia Adaptions After Focal Injury

4.1.4. Stable NeuN Expression with Potential Subcellular Dysfunction After Focal Injury

4.2. Glial and Neuroendocrine Mechanisms of Persistent Motor Deficits After TBI

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| HL-PA | Hindlimb postural asymmetry |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular pattern |

| NF-κβ | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| IL | Interleukins |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| FPI | Fluid percussion injury |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| CCI | Controlled cortical impact |

| CD11b | Cluster of differentiation 11b |

| IBA-1 | Ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 |

| i.p. | Intraperitoneally |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| NeuN | Neuronal nuclei antige |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| NGS | Normal goat serum |

| RT | Room temperature |

| DAB | 3,3′-diaminobenzidine |

| LFPI | Lateral fluid percussion injury |

| CCR2 | C-C chemokine receptor type 2 |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CSPG | Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| HMGB1 | High mobility group box 1 |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| AVP | Vasopressin |

| OXT | Oxytocin |

References

- Obasa, A.A.; Olopade, F.E.; Juliano, S.L.; Olopade, J.O. Traumatic brain injury or traumatic brain disease: A scientific commentary. Brain Multiphysics 2024, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, M.C.; Rattani, A.; Gupta, S.; Baticulon, R.E.; Hung, Y.C.; Punchak, M.; Agrawal, A.; Adeleye, A.O.; Shrime, M.G.; Rubiano, A.M.; et al. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 130, 1080–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Ren, R.; Chen, T.; Su, L.D.; Tang, T. Neuroimmune and neuroinflammation response for traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 217, 111066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michinaga, S.; Koyama, Y. Pathophysiological responses and roles of astrocytes in traumatic brain injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, F.; Wee, I.C.; Collins-Praino, L.E. Chronic motor performance following different traumatic brain injury severity-A systematic review. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1180353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.S.; Güler, D.B.; Larsen, J.; Rich, K.K.; Svenningsen, Å.F.; Zhang, M. The Development of Hindlimb Postural Asymmetry Induced by Focal Traumatic Brain Injury Is Not Related to Serotonin 2A/C Receptor Expression in the Spinal Cord. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amlerova, Z.; Chmelova, M.; Anderova, M.; Vargova, L. Reactive gliosis in traumatic brain injury: A comprehensive review. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1335849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fesharaki-Zadeh, A.; Datta, D. An overview of preclinical models of traumatic brain injury (TBI): Relevance to pathophysiological mechanisms. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1371213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Watanabe, H.; Sarkisyan, D.; Andersen, M.S.; Nosova, O.; Galatenko, V.; Carvalho, L.; Lukoyanov, N.; Thelin, J.; Schouenborg, J.; et al. Hindlimb motor responses to unilateral brain injury: Spinal cord encoding and left-right asymmetry. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.B.; Nagai, A.; Kim, S.U. Cytokines, chemokines, and cytokine receptors in human microglia. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 69, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, Y.; Ibata, I.; Ito, D.; Ohsawa, K.; Kohsaka, S. A Novel Gene iba1 in the Major Histocompatibility Complex Class III Region Encoding an EF Hand Protein Expressed in a Monocytic Lineage 1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 224, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, D.; Imai, Y.; Ohsawa, K.; Nakajima, K.; Fukuuchi, Y.; Kohsaka, S. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Mol. Brain Res. 1998, 57, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, C.W.; Zhan, K.B.; Yang, M.; Wen, M.; Zhu, L.Q. Revisiting the critical roles of reactive microglia in traumatic brain injury. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 3942–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Pickard, J.D.; Harris, N.G. Time course of cellular pathology after controlled cortical impact injury. Exp. Neurol. 2003, 182, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, R.J.; Buck, C.R.; Smith, A.M. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development 1992, 116, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Ishii, H.; Bai, Z.; Itokazu, T.; Yamashita, T. Temporal changes in cell marker expression and cellular infiltration in a controlled cortical impact model in adult male C57BL/6 mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.L.; Niemi, E.C.; Wang, S.H.; Lee, C.C.; Bingham, D.; Zhang, J.; Cozen, M.L.; Charo, I.; Huang, E.J.; Liu, J.; et al. CCR2 deficiency impairs macrophage infiltration and improves cognitive function after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 1677–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, J.M.; Jopson, T.D.; Liu, S.; Riparip, L.K.; Guandique, C.K.; Gupta, N.; Ferguson, A.R.; Rosi, S. CCR2 antagonism alters brain macrophage polarization and ameliorates cognitive dysfunction induced by traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 748–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.L.; Kim, C.C.; Ryba, B.E.; Niemi, E.C.; Bando, J.K.; Locksley, R.M.; Liu, J.; Nakamura, M.C.; Seaman, W.E. Traumatic brain injury induces macrophage subsets in the brain. Eur. J. Immunol. 2013, 43, 2010–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turtzo, L.C.; Lescher, J.; Janes, L.; Dean, D.D.; Budde, M.D.; Frank, J.A. Macrophagic and microglial responses after focal traumatic brain injury in the female rat. J. Neuroinflammation 2014, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyoneva, S.; Kim, D.; Katsumoto, A.; Kokiko-Cochran, O.N.; Lamb, B.T.; Ransohoff, R.M. Ccr2 deletion dissociates cavity size and tau pathology after mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, A.; Krukowski, K.; Morganti, J.M.; Riparip, L.K.; Rosi, S. Persistent infiltration and impaired response of peripherally-derived monocytes after traumatic brain injury in the aged brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukowski, K.; Nolan, A.; Becker, M.; Picard, K.; Vernoux, N.; Frias, E.S.; Feng, X.; Tremblay, M.E.; Rosi, S. Novel microglia-mediated mechanisms underlying synaptic loss and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Brain Behav. Immun. 2021, 98, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witcher, K.G.; Bray, C.E.; Chunchai, T.; Zhao, F.; O’Neil, S.M.; Gordillo, A.J.; Campbell, W.A.; McKim, D.B.; Liu, X.; Dziabis, J.E.; et al. Traumatic Brain Injury Causes Chronic Cortical Inflammation and Neuronal Dysfunction Mediated by Microglia. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 1597–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, M.B.; Oshinsky, M.L.; Amenta, P.S.; Awe, O.O.; Jallo, J.I. Nociceptive neuropeptide increases and periorbital allodynia in a model of traumatic brain injury. Headache 2012, 52, 966–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Hwang, J.; Yoo, J.; Choi, J.; Ramalingam, M.; Kim, S.; Cho, H.H.; Kim, B.C.; Jeong, H.S.; Jang, S. The time-dependent changes in a mouse model of traumatic brain injury with motor dysfunction. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, H.W.; Cardenas, F.; Gudenkauf, F.; Zelnick, P.; Xue, H.; Cox, C.S.; Bedi, S.S. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Microglia After Traumatic Brain Injury in Male Mice. ASN Neuro 2020, 12, 1759091420911770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankowski, J.C.; Foik, A.T.; Tierno, A.; Machhor, J.R.; Lyon, D.C.; Hunt, R.F. Traumatic brain injury to primary visual cortex produces long-lasting circuit dysfunction. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, H.; Young, K.; Qureshi, M.; Rowe, R.K.; Lifshitz, J. Quantitative microglia analyses reveal diverse morphologic responses in the rat cortex after diffuse brain injury. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villapol, S.; Byrnes, K.R.; Symes, A.J. Temporal dynamics of cerebral blood flow, cortical damage, apoptosis, astrocyte-vasculature interaction and astrogliosis in the pericontusional region after traumatic brain injury. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzy, S.; Liu, Q.; Fang, Z.; Lule, S.; Wu, L.; Chung, J.Y.; Sarro-Schwartz, A.; Brown-Whalen, A.; Perner, C.; Hickman, S.E.; et al. Time-Dependent Changes in Microglia Transcriptional Networks Following Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Xu, X.; Li, M.; Tian, R.; Zhuang, Y.; Gao, G. Contralateral Structure and Molecular Response to Severe Unilateral Brain Injury. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Münch, A.E.; Chung, W.S.; Peterson, T.C.; et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badimon, A.; Strasburger, H.J.; Ayata, P.; Chen, X.; Nair, A.; Ikegami, A.; Hwang, P.; Chan, A.T.; Graves, S.M.; Uweru, J.O.; et al. Negative feedback control of neuronal activity by microglia. Nature 2020, 586, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziebell, J.M.; Taylor, S.E.; Cao, T.; Harrison, J.L.; Lifshitz, J. Rod microglia: Elongation, alignment, and coupling to form trains across the somatosensory cortex after experimental diffuse brain injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalancette-Hébert, M.; Gowing, G.; Simard, A.; Weng, Y.C.; Kriz, J. Selective ablation of proliferating microglial cells exacerbates ischemic injury in the brain. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 2596–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loane, D.J.; Kumar, A. Microglia in the TBI brain: The good, the bad, and the dysregulated. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, W.D.; Truettner, J.; Zhao, W.; Alonso, O.F.; Busto, R.; Ginsberg, M.D. Sequential changes in glial fibrillary acidic protein and gene expression following parasagittal fluid-percussion brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 1999, 16, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Shao, L.; Guo, Z.; Li, Y. Morphological and functional alterations of astrocytes responding to traumatic brain injury. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2019, 18, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautz, F.; Franke, H.; Bohnert, S.; Hammer, N.; Müller, W.; Stassart, R.; Tse, R.; Zwirner, J.; Dreßler, J.; Ondruschka, B. Survival-time dependent increase in neuronal IL-6 and astroglial GFAP expression in fatally injured human brain tissue. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramlackhansingh, A.F.; Brooks, D.J.; Greenwood, R.J.; Bose, S.K.; Turkheimer, F.E.; Kinnunen, K.M.; Gentleman, S.; Heckemann, R.A.; Gunanayagam, K.; Gelosa, G.; et al. Inflammation after trauma: Microglial activation and traumatic brain injury. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 70, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burda, J.E.; Bernstein, A.M.; Sofroniew, M.V. Astrocyte roles in traumatic brain injury. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 275, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, A.R.; Tong, X.Y.; Ruiz-Cordero, R.; Bregy, A.; Bethea, J.R.; Bramlett, H.M.; Norenberg, M.D. Activation of NF-κB mediates astrocyte swelling and brain edema in traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, F.; Iqbal, K.; Gong, C.X.; Hu, W.; Liu, F. Subacute to chronic Alzheimer-like alterations after controlled cortical impact in human tau transgenic mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Zeitouni, S.; Cavarsan, C.F.; Shapiro, L.A. Increased seizure susceptibility in mice 30 days after fluid percussion injury. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yin, D.; Ren, H.; Gao, W.; Li, F.; Sun, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Lyu, L.; Yang, M.; et al. Selective NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor reduces neuroinflammation and improves long-term neurological outcomes in a murine model of traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 117, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Chai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X. Astrocyte-mediated inflammatory responses in traumatic brain injury: Mechanisms and potential interventions. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1584577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoog, Q.P.; Holtman, L.; Aronica, E.; van Vliet, E.A. Astrocytes as Guardians of Neuronal Excitability: Mechanisms Underlying Epileptogenesis. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 591690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.P.Q.; Perreau, V.M.; Shultz, S.R.; Brady, R.D.; Lei, E.; Dixit, S.; Taylor, J.M.; Beart, P.M.; Boon, W.C. Inflammation in Traumatic Brain Injury: Roles for Toxic A1 Astrocytes and Microglial-Astrocytic Crosstalk. Neurochem. Res. 2019, 44, 1410–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiareli, R.A.; Carvalho, G.A.; Marques, B.L.; Mota, L.S.; Oliveira-Lima, O.C.; Gomes, R.M.; Birbrair, A.; Gomez, R.S.; Simão, F.; Klempin, F.; et al. The Role of Astrocytes in the Neurorepair Process. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 665795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadidi, Q.M.; Bahader, G.A.; Arvola, O.; Kitchen, P.; Shah, Z.A.; Salman, M.M. Astrocytes in functional recovery following central nervous system injuries. J. Physiol. 2024, 602, 3069–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, L.; Zhang, T.; Fan, K.; Cai, W.; Liu, H. Astrocyte-Neuron Signaling in Synaptogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 680301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, M.L.; Chatlos, T.; Gorse, K.M.; Lafrenaye, A.D. Neuronal Membrane Disruption Occurs Late Following Diffuse Brain Trauma in Rats and Involves a Subpopulation of NeuN Negative Cortical Neurons. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz-Ballester, C.; Mahmutovic, D.; Rafiqzad, Y.; Korot, A.; Robel, S. Mild Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Disruption of the Blood-Brain Barrier Triggers an Atypical Neuronal Response. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 821885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.D.; Bryant, Y.D.; Cho, W.; Sullivan, P.G. Evolution of post-traumatic neurodegeneration after controlled cortical impact traumatic brain injury in mice and rats as assessed by the de Olmos silver and fluorojade staining methods. J. Neurotrauma 2008, 25, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Deng-Bryant, Y.; Cho, W.; Carrico, K.M.; Hall, E.D.; Chen, J. Selective death of newborn neurons in hippocampal dentate gyrus following moderate experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 86, 2258–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madathil, S.K.; Carlson, S.W.; Brelsfoard, J.M.; Ye, P.; D’Ercole, A.J.; Saatman, K.E. Astrocyte-Specific Overexpression of Insulin-Like Growth Factor-1 Protects Hippocampal Neurons and Reduces Behavioral Deficits following Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Jin, R.; Xiao, A.Y.; Chen, R.; Li, J.; Zhong, W.; Feng, X.; Li, G. Induction of Neuronal PI3Kγ Contributes to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Long-Term Functional Impairment in a Murine Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurotherapeutics 2019, 16, 1320–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, G.B.; Fan, L.; Levasseur, R.A.; Faden, A.I. Sustained sensory/motor and cognitive deficits with neuronal apoptosis following controlled cortical impact brain injury in the mouse. J. Neurotrauma 1998, 15, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.D.; Sullivan, P.G.; Gibson, T.R.; Pavel, K.M.; Thompson, B.M.; Scheff, S.W. Spatial and temporal characteristics of neurodegeneration after controlled cortical impact in mice: More than a focal brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2005, 22, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Mao, J.; Hou, L.; Jin, S.; Wang, X.; Ding, Z.; Jin, Z.; Guo, H.; Dai, R. Minocycline attenuates neuronal apoptosis and improves motor function after traumatic brain injury in rats. Exp. Anim. 2021, 70, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, R.K.; Harrison, J.L.; Zhang, H.; Bachstetter, A.D.; Hesson, D.P.; O’Hara, B.F.; Greene, M.I.; Lifshitz, J. Novel TNF receptor-1 inhibitors identified as potential therapeutic candidates for traumatic brain injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.C.; Garnett, C.N.; Watson, J.B.; Higgins, E.K.; Macheda, T.; Sanders, L.; Roberts, K.N.; Shahidehpour, R.K.; Blalock, E.M.; Quan, N.; et al. IL-1R1 signaling in TBI: Assessing chronic impacts and neuroinflammatory dynamics in a mouse model of mild closed-head injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.N.; Donovan, M.H.; Smith, K.; Noble-Haeusslein, L.J. Traumatic Injury to the Developing Brain: Emerging Relationship to Early Life Stress. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 708800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.L.; Yu, X.; Xia, L.; Xie, Y.D.; Qi, E.B.; Wan, L.; Hua, X.M.; Jing, C.H. A new perspective on the regulation of neuroinflammation in intracerebral hemorrhage: Mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and therapeutic strategies. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1526786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.H.; Gangidine, M.; Pritts, T.A.; Goodman, M.D.; Lentsch, A.B. Interleukin 6 mediates neuroinflammation and motor coordination deficits after mild traumatic brain injury and brief hypoxia in mice. Shock 2013, 40, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napieralski, J.A.; Banks, R.J.; Chesselet, M.F. Motor and somatosensory deficits following uni- and bilateral lesions of the cortex induced by aspiration or thermocoagulation in the adult rat. Exp. Neurol. 1998, 154, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, M.A.; Rich, K.K.; Mogensen, T.C.; Damsgaard Jensen, A.M.; Fex Svenningsen, Å.; Zhang, M. Focal Traumatic Brain Injury Impairs the Integrity of the Basement Membrane of Hindlimb Muscle Fibers Revealed by Extracellular Matrix Immunoreactivity. Life 2024, 14, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkhurst, C.N.; Yang, G.; Ninan, I.; Savas, J.N.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Lafaille, J.J.; Hempstead, B.L.; Littman, D.R.; Gan, W.B. Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Cell 2013, 155, 1596–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Shi, X.J.; Qi, L.; Wang, C.; Mamtilahun, M.; Zhang, Z.J.; Chung, W.S.; Yang, G.Y.; Tang, Y.H. Microglia and astrocytes mediate synapse engulfment in a MER tyrosine kinase-dependent manner after traumatic brain injury. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1770–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, R.G.; Lira, M.; Cerpa, W. Traumatic Brain Injury: Mechanisms of Glial Response. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 740939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, U.; Patro, N.; Patro, I.K. Astrogliosis and associated CSPG upregulation adversely affect dendritogenesis, spinogenesis and synaptic activity in the cerebellum of a double-hit rat model of protein malnutrition (PMN) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced bacterial infection. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2023, 131, 102286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmydynger-Chodobska, J.; Chung, I.; Koźniewska, E.; Tran, B.; Harrington, F.J.; Duncan, J.A.; Chodobski, A. Increased expression of vasopressin v1a receptors after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2004, 21, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmydynger-Chodobska, J.; Fox, L.M.; Lynch, K.M.; Zink, B.J.; Chodobski, A. Vasopressin amplifies the production of proinflammatory mediators in traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 1449–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukoyanov, N.; Watanabe, H.; Carvalho, L.S.; Kononenko, O.; Sarkisyan, D.; Zhang, M.; Andersen, M.S.; Lukoyanova, E.A.; Galatenko, V.; Tonevitsky, A.; et al. Left-right side-specific endocrine signaling complements neural pathways to mediate acute asymmetric effects of brain injury. Elife 2021, 10, e65247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.N.; Rahman, S.U.; Tio, D.L.; Sanders, M.J.; Bando, J.K.; Truong, A.H.; Prolo, P. Lasting neuroendocrine-immune effects of traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma 2006, 23, 1802–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.N.; Rahman, S.U.; Sanders, N.C.; Tio, D.L.; Prolo, P.; Sutton, R.L. Injury severity differentially affects short- and long-term neuroendocrine outcomes of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 2008, 25, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, H.; Kobikov, Y.; Nosova, O.; Sarkisyan, D.; Galatenko, V.; Carvalho, L.; Maia, G.H.; Lukoyanov, N.; Lavrov, I.; Ossipov, M.H.; et al. The Left-Right Side-Specific Neuroendocrine Signaling from Injured Brain: An Organizational Principle. Function 2024, 5, zqae013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Nosova, O.; Sarkisyan, D.; Storm Andersen, M.; Carvalho, L.; Galatenko, V.; Bazov, I.; Lukoyanov, N.; Maia, G.H.; Hallberg, M.; et al. Left-Right Side-Specific Neuropeptide Mechanism Mediates Contralateral Responses to a Unilateral Brain Injury. eNeuro 2021, 8, ENEURO.0548-20.2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rich, K.K.; Hjæresen, S.; Andersen, M.S.; Hansen, L.B.; Mohammad, A.S.; Gopinathan, N.; Mogensen, T.C.; Fex Svenningsen, Å.; Zhang, M. Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Glial Activation After Unilateral Cortical Injury in Rats. Life 2026, 16, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010142

Rich KK, Hjæresen S, Andersen MS, Hansen LB, Mohammad AS, Gopinathan N, Mogensen TC, Fex Svenningsen Å, Zhang M. Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Glial Activation After Unilateral Cortical Injury in Rats. Life. 2026; 16(1):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010142

Chicago/Turabian StyleRich, Karen Kalhøj, Simone Hjæresen, Marlene Storm Andersen, Louise Bjørnager Hansen, Ali Salh Mohammad, Nilukshi Gopinathan, Tobias Christian Mogensen, Åsa Fex Svenningsen, and Mengliang Zhang. 2026. "Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Glial Activation After Unilateral Cortical Injury in Rats" Life 16, no. 1: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010142

APA StyleRich, K. K., Hjæresen, S., Andersen, M. S., Hansen, L. B., Mohammad, A. S., Gopinathan, N., Mogensen, T. C., Fex Svenningsen, Å., & Zhang, M. (2026). Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Glial Activation After Unilateral Cortical Injury in Rats. Life, 16(1), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/life16010142