Assessment of Hypertension in Hemodialysis Patients with the Concomitant Use of Peridialytic and Interdialytic Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurements

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. BP Measurements

2.2.1. Interdialytic ABPM

2.2.2. Routine Peridialytic BP Recordings

2.3. Definitions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

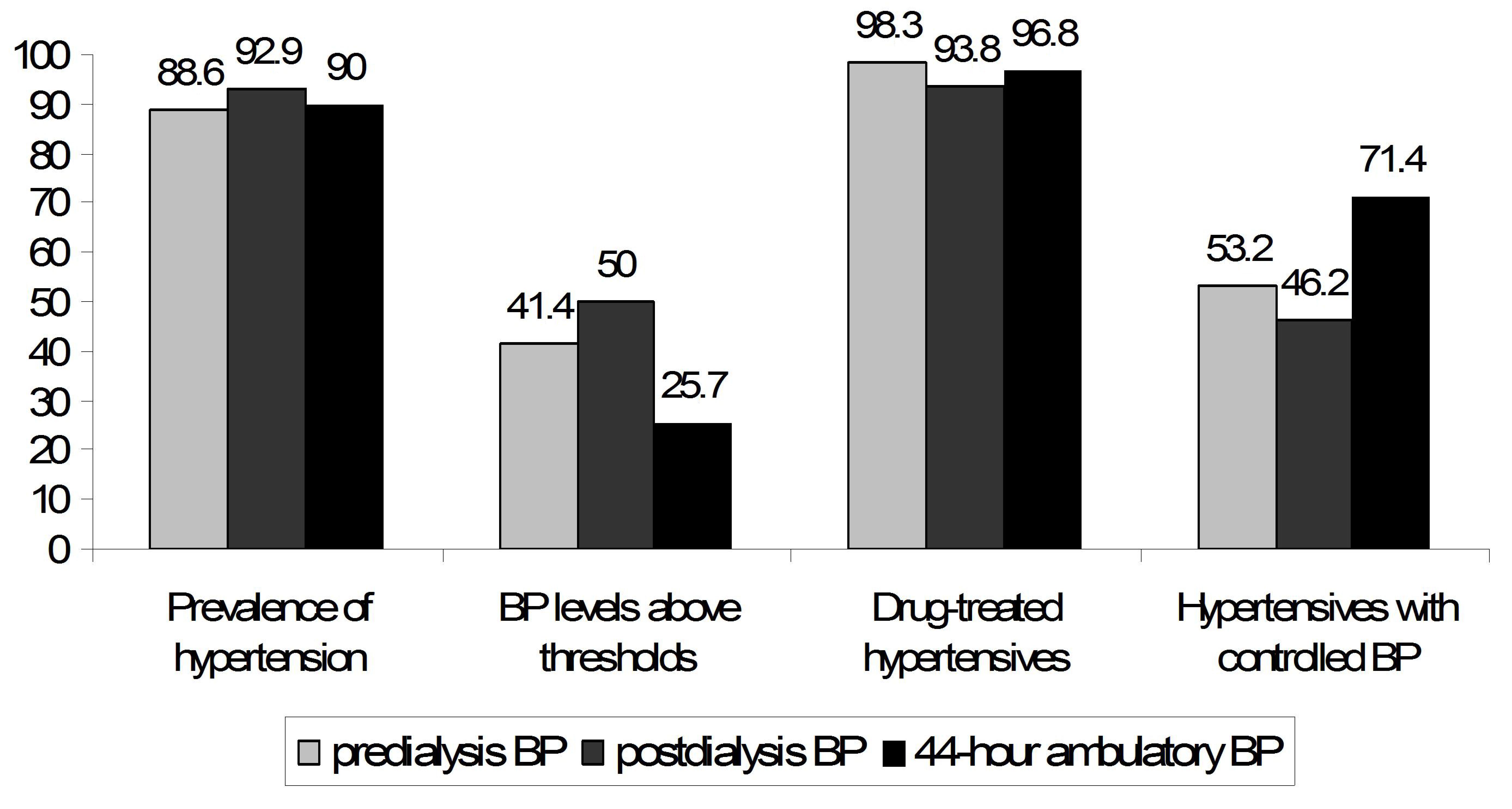

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABPM | Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| ESH | European Society of Hypertension |

| ROC | Receiver operator characteristic |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

References

- Georgianos, P.I.; Agarwal, R. Epidemiology, diagnosis and management of hypertension among patients on chronic dialysis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, N.; Artinian, N.T.; Bakris, G.; Chang, T.; Cohen, J.; Flythe, J.; Lea, J.; Vongpatanasin, W.; Chertow, J.M.; American Heart Association Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; et al. Hypertension in Patients Treated With In-Center Maintenance Hemodialysis: Current Evidence and Future Opportunities: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2023, 80, e112–e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Nissenson, A.R.; Batlle, D.; Coyne, D.W.; Trout, J.R.; Warnock, D.G. Prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension in chronic hemodialysis patients in the United States. Am. J. Med. 2003, 115, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, L.; Lusenti, T.; Del Rosso, G.; Malandra, R.; Balducci, A.; Losito, A. Prevalence of hypertension in a large cohort of Italian hemodialysis patients: Results of a cross-sectional study. J. Nephrol. 2013, 26, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikliras, N.; Georgianos, P.I.; Vaios, V.; Minasidis, E.; Anagnostara, A.; Chatzidimitriou, C.; Syrganis, C.; Liakopoulos, V.; Zebekakis, P.E.; Balaskas, E.V. Prevalence and control of hypertension among patients on haemodialysis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 50, e13292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Peixoto, A.J.; Santos, S.F.; Zoccali, C. Pre- and postdialysis blood pressures are imprecise estimates of interdialytic ambulatory blood pressure. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 1, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Brim, N.J.; Mahenthiran, J.; Andersen, M.J.; Saha, C. Out-of-hemodialysis-unit blood pressure is a superior determinant of left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertension 2006, 47, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R. Blood pressure and mortality among hemodialysis patients. Hypertension 2010, 55, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alborzi, P.; Patel, N.; Agarwal, R. Home blood pressures are of greater prognostic value than hemodialysis unit recordings. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 2, 1228–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, C.C.; Matschkal, J.; Sarafidis, P.A.; Hagmair, S.; Lorenz, G.; Angermann, S.; Braunisch, M.C.; Baumann, M.; Heemann, U.; Wassertheurer, S.; et al. Association of Ambulatory Blood Pressure with All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients: Effects of Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2409–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R. Pro: Ambulatory blood pressure should be used in all patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015, 30, 1432–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R. Epidemiology of interdialytic ambulatory hypertension and the role of volume excess. Am. J. Nephrol. 2011, 34, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafidis, P.A.; Mallamaci, F.; Loutradis, C.; Ekart, R.; Torino, C.; Karpetas, A.; Raptis, V.; Bikos, A.; Papagianni, A.; Balafa, O.; et al. Prevalence and control of hypertension by 48-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in haemodialysis patients: A study by the European Cardiovascular and Renal Medicine (EURECA-m) working group of the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2019, 34, 1542–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fania, C.; Lazzaretto, I.; Fontana, U.; Palatini, P. Accuracy of the WatchBP O3 device for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring according to the new criteria of the ISO81060-2 2018 protocol. Blood Press. Monit. 2020, 25, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stergiou, G.S.; Palatini, P.; Parati, G.; O’Brien, E.; Januszewicz, A.; Lurbe, E.; Persu, A.; Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R. 2021 European Society of Hypertension practice guidelines for office and out-of-office blood pressure measurement. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 1293–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancia, G.; Kreutz, R.; Brunstrom, M.; Burnier, M.; Grassi, G.; Januszewicz, A.; Muiesan, M.L.; Tsioufis, K.; Agabiti-Rosei, E.; Algharably, E.A.E.; et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA). J. Hypertens. 2023, 41, 1874–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Unal, I. Defining an Optimal Cut-Point Value in ROC Analysis: An Alternative Approach. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2017, 2017, 3762651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Sinha, A.D.; Light, R.P. Toward a definition of masked hypertension and white-coat hypertension among hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 2003–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgianos, P.I.; Agarwal, R. Can We Mend the Broken Clock by Timing Antihypertensive Therapy Sensibly? Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 1513–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, J.; Vernier, I.; Rossignol, E.; Bongard, V.; Arnaud, C.; Conte, J.J.; Salvador, M.; Chamontin, B. Nocturnal blood pressure and 24-h pulse pressure are potent indicators of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2000, 57, 2485–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Griffin, V.; Heyka, R.; Hoit, B. Diurnal variation of blood pressure; reproducibility and association with left ventricular hypertrophy in hemodialysis patients. Blood Press. Monit. 2005, 10, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripepi, G.; Fagugli, R.M.; Dattolo, P.; Parlongo, G.; Mallamaci, F.; Buoncristiani, U.; Zoccali, C. Prognostic value of 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and of night/day ratio in nondiabetic, cardiovascular events-free hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2005, 68, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, R.; Lewis, R.R. Prediction of hypertension in chronic hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2001, 60, 1982–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.; Griffin, V.; Kumar, A.; Manzoor, F.; Wright, J.T.; Smith, M.C. A comparison of standardized versus “usual” blood pressure measurements in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2002, 39, 1226–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clinical Characteristic | Overall | 44-Hour Ambulatory BP < 130/80 mmHg | 44-Hour Ambulatory BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 70 | 52 | 18 | - |

| Age (years) | 65.3 ± 13.2 | 66.7 ± 12.8 | 61.4 ± 14.1 | 0.151 |

| Male gender (n,%) | 45 (64.3%) | 31 (59.6%) | 14 (77.8%) | 0.254 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.5 ± 4.1 | 26.2 ± 4.2 | 23.3 ± 2.6 | 0.008 |

| Dialysis vintage (months) | 15 (3, 117) | 14 (3, 117) | 27 (3, 90) | 0.407 |

| Comorbidities (n,%) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 34 (48.6%) | 27 (51.9%) | 7 (38.9%) | 0.417 |

| Coronary artery disease | 22 (31.4%) | 17 (32.7%) | 5 (27.8%) | 0.776 |

| Congestive heart failure | 12 (17.1%) | 11 (21.2%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0.166 |

| Dyslipidemia | 44 (62.9%) | 35 (67.3%) | 9 (50.0%) | 0.259 |

| Basic laboratory parameters | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.6 ± 0.8 | 11.5 ± 0.8 | 12.2 ± 0.8 | 0.008 |

| Serum urea (mg/dL) | 135.8 ± 23.8 | 132.3 ± 23.2 | 146.2 ± 23.1 | 0.037 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 7.3 ± 2.5 | 7.4 ± 2.4 | 6.8 ± 2.8 | 0.420 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 0.809 |

| BP values | ||||

| 44 h ambulatory SBP (mmHg) | 120.6 ± 15.2 | 114.2 ± 10.8 | 139.1 ± 9.6 | <0.001 |

| 44 h ambulatory SBP (mmHg) | 66.3 ± 10.1 | 62.6 ± 8.3 | 77.0 ± 6.5 | <0.001 |

| 2-week averaged predialysis SBP (mmHg) | 134.2 ± 14.2 | 130.7 ± 12.9 | 144.3 ± 13.1 | <0.001 |

| 2-week averaged predialysis DBP (mmHg) | 76.6 ± 9.2 | 74.8 ± 9.0 | 81.7 ± 7.7 | 0.005 |

| 2-week averaged postdialysis SBP (mmHg) | 126.7 ± 15.8 | 122.9 ± 13.5 | 137.9 ± 16.9 | <0.001 |

| 2-week averaged postdialysis DBP (mmHg) | 75.8 ± 10.3 | 74.1 ± 10.4 | 80.4 ± 8.7 | 0.016 |

| Antihypertensive drug use (n,%) | 61 (87.1%) | 45 (86.5%) | 16 (88.9%) | 0.799 |

| Average number of BP-lowering medications in users (n,%) | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 0.125 |

| Parameter | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude OR | 95% CI | p Value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age (per 1 year higher) | 0.973 | 0.934–1.013 | 0.18 | 0.954 | 0.903–1.009 | 0.10 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 2.333 | 0.661–8.235 | 0.19 | 2.640 | 0.439–15.888 | 0.29 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2 higher) | 0.810 | 0.670–0.979 | 0.03 | 0.739 | 0.581–1.081 | 0.14 |

| Dialysis vintage (per 1 month higher) | 1.002 | 0.983–1.021 | 0.84 | - | - | - |

| Current smoker (yes vs. no) | 1.132 | 0.308–4.166 | 0.85 | - | - | - |

| History of diabetes mellitus (yes vs. no) | 1.643 | 0.540–5.002 | 0.38 | - | - | - |

| History of coronary artery disease (yes vs. no) | 1.174 | 0.350–3.934 | 0.79 | - | - | - |

| History of dyslipidemia (yes vs. no) | 2.000 | 0.657–6.084 | 0.22 | - | - | - |

| History of heart failure (yes vs. no) | 3.679 | 0.425–31.768 | 0.24 | - | - | - |

| Hemoglobin (per 1 g/dL higher) | 3.227 | 1.334–7.805 | 0.01 | 4.902 | 1.268–18.953 | 0.02 |

| Serum albumin (per 1 g/dL higher) | 1.273 | 0.257–6.308 | 0.77 | - | - | - |

| Number of antihypertensives (per 1 agent higher) | 2.307 | 0.955–5.574 | 0.06 | 3.835 | 1.219–12.068 | 0.02 |

| Blood Pressure Phenotype | Predialysis and Ambulatory | Postdialysis and Ambulatory |

|---|---|---|

| Normotension or controlled hypertension, n (%) | 37 (52.9%) | 35 (50.0%) |

| White-coat hypertension, n (%) | 15 (21.4%) | 17 (24.3%) |

| Masked hypertension, n (%) | 4 (5.7%) | 4 (5.7%) |

| Sustained hypertension, n (%) | 14 (20.0%) | 14 (20.0%) |

| Nighttime BP Levels | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥120/70 mmHg | <120/70 mmHg | |||

| Daytime BP levels | ≥135/85 mmHg | 15 (21.5%) | 1 (1.4%) | 16 (22.9%) |

| <135/85 mmHg | 19 (27.1%) | 35 (50.0%) | 54 (77.1%) | |

| Total | 34 (48.6%) | 36 (51.4%) | 70 (100%) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leonidou, K.; Kontogiorgos, I.; Kourtidou, C.; Georgianou, E.; Rafailidis, V.; Roumeliotis, S.; Leivaditis, K.; Balaskas, E.V.; Liakopoulos, V.; Georgianos, P.I. Assessment of Hypertension in Hemodialysis Patients with the Concomitant Use of Peridialytic and Interdialytic Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurements. Life 2025, 15, 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15081290

Leonidou K, Kontogiorgos I, Kourtidou C, Georgianou E, Rafailidis V, Roumeliotis S, Leivaditis K, Balaskas EV, Liakopoulos V, Georgianos PI. Assessment of Hypertension in Hemodialysis Patients with the Concomitant Use of Peridialytic and Interdialytic Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurements. Life. 2025; 15(8):1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15081290

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonidou, Kallistheni, Ioannis Kontogiorgos, Christodoula Kourtidou, Eleni Georgianou, Vasileios Rafailidis, Stefanos Roumeliotis, Konstantinos Leivaditis, Elias V. Balaskas, Vassilios Liakopoulos, and Panagiotis I. Georgianos. 2025. "Assessment of Hypertension in Hemodialysis Patients with the Concomitant Use of Peridialytic and Interdialytic Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurements" Life 15, no. 8: 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15081290

APA StyleLeonidou, K., Kontogiorgos, I., Kourtidou, C., Georgianou, E., Rafailidis, V., Roumeliotis, S., Leivaditis, K., Balaskas, E. V., Liakopoulos, V., & Georgianos, P. I. (2025). Assessment of Hypertension in Hemodialysis Patients with the Concomitant Use of Peridialytic and Interdialytic Ambulatory Blood Pressure Measurements. Life, 15(8), 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15081290