Inherited Hemophilia—A Multidimensional Chronic Disease That Requires a Multidisciplinary Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Measuring Tools

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

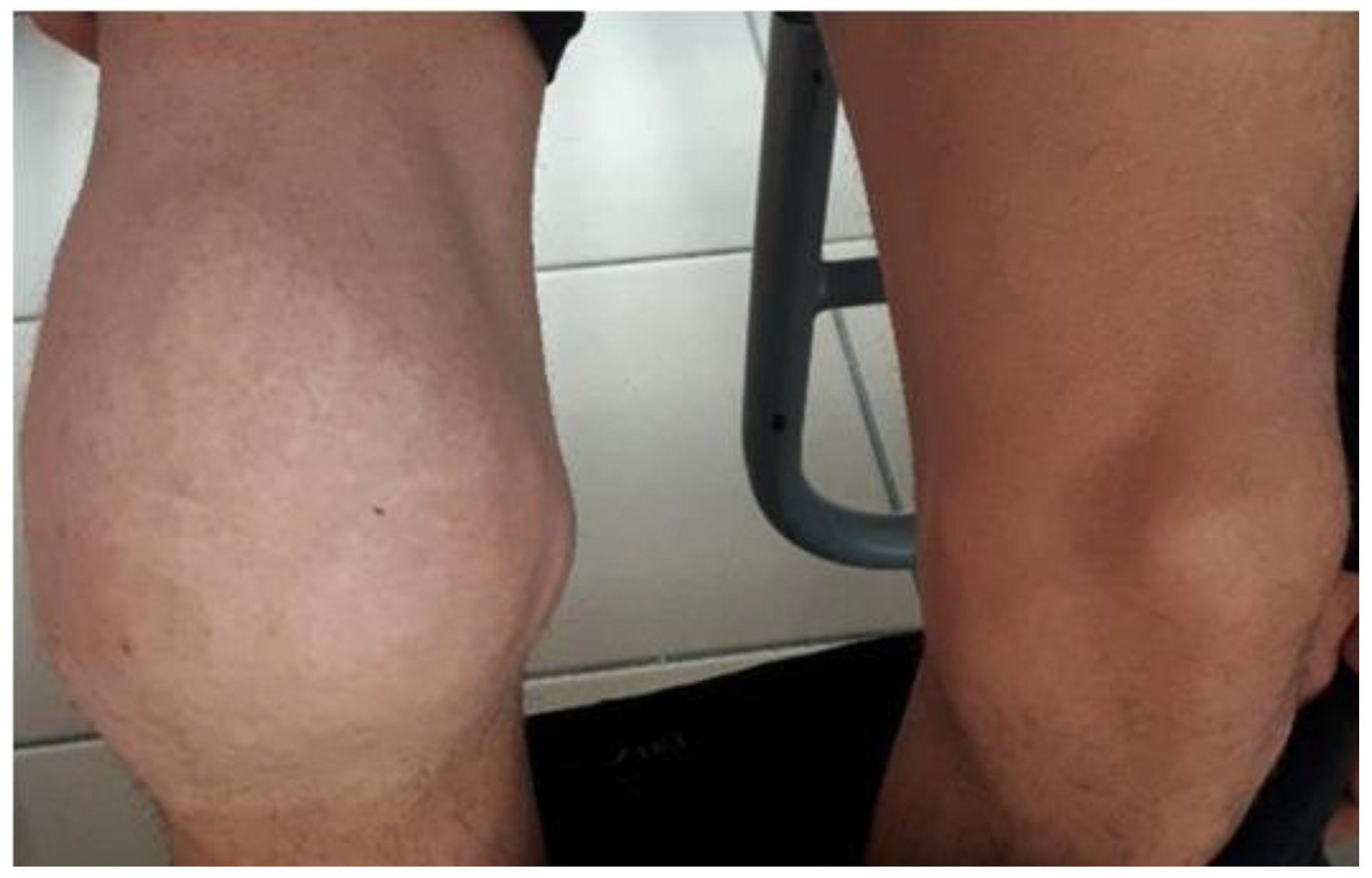

3.2. Articular Damage

3.2.1. Distribution of Severity of Articular Damage

3.2.2. Correlation Between Form of Hemophilia and Joint Damage

- -

- A total of 53.6% of patients associated severe hemophilia with severe damage to the right knee, while in patients with mild hemophilia, damage to the right knee was absent in all patients (p = 0.028).

- -

- In the left knee, severe hemophilia was associated with severe damage in 39.3% of patients, while in patients with mild hemophilia, damage to the left knee was absent in all patients (p = 0.035).

- -

- A total of 32.1% of patients associated severe hemophilia with severe damage to the right ankle, while in patients with mild hemophilia, damage to the right ankle was absent in all patients, and in those with moderate hemophilia, damage to the right knee was mild in all patients (p = 0.001).

- -

- A total of 25% of patients associated severe hemophilia with severe damage to the left knee, while in patients with mild hemophilia, damage to the left knee was absent in all patients, and in those with moderate hemophilia, damage to the left knee was mild in all patients (p = 0.001).

- -

- A total of 25% of patients associated moderate hemophilia and 14.3% associated severe hemophilia with severe damage to the right hip (p = 0.709).

- -

- A total of 25% of patients associated moderate hemophilia and 14.3% associated severe hemophilia with severe damage to the left hip (p = 0.605).

- -

- A total of 14.3% of patients associated severe hemophilia with severe damage to the right wrist, while mild hemophilia was not associated with damage to the right wrist (p = 0.243).

- -

- Severe hemophilia was associated with mild and moderate left wrist damage in 42.8% of patients, while in patients with mild hemophilia, left wrist damage was absent in all patients (p = 0.303).

- -

- A total of 25% of patients associated severe hemophilia with severe damage to the right elbow, while patients with mild hemophilia did not show damage to the right elbow (p = 0.007).

- -

- In the left elbow, severe hemophilia was associated with moderate and severe damage in 53.5% of patients, while in patients with mild hemophilia, damage to the left fist was absent in all patients (p = 0.029).

- -

- All patients with mild hemophilia, 75% of patients with moderate hemophilia, and 60.7% of patients with severe hemophilia did not have damage to the right shoulder (p = 0.508).

- -

- All patients with mild hemophilia, 75% of patients with moderate hemophilia, and 75% of patients with severe hemophilia did not have damage to the left shoulder (p = 0.529).

3.2.3. Correlation Between Treatment and Joint Damage

- -

- A total of 57.1% of patients with continuous prophylaxis did not have right knee damage, while 72% of patients with short-term replacement had severe right knee damage (p = 0.001) (Table 5).

- -

- A total of 85.7% of patients with continuous prophylaxis had no left knee damage, while 48% of short-term substitution patients had severe left knee damage (p = 0.001) (Table 5).

- -

- A total of 42.9% of patients with continuous prophylaxis had mild right ankle involvement, while 36% of short-term substitution patients had severe right ankle involvement (p = 0.05) (Table 5).

- -

- A total of 76.7% of patients with continuous prophylaxis and 83.3% of patients with short-term substitution associated mild damage to the left ankle (p = 0.019) (Table 5).

- -

- All patients with continuous prophylaxis and 64% of those with short-term substitution did not have a correlation with right hip damage (p = 0.148) (Table 5).

- -

- All patients with continuous prophylaxis and 56% of those with short-term substitution did not associate damage to the left hip (p = 0.076) (Table 5).

- -

- All patients with continuous prophylaxis did not present damage to the right hip, while 36% of those with short-term substitution are associated with moderate-severe damage to the right hip (p = 0.014) (Table 5).

- -

- All patients with continuous prophylaxis did not have damage to the right wrist, while 36% of those with short-term substitution had an association with moderate–severe damage to the right wrist (p = 0.014) (Table 5).

- -

- All patients with continuous prophylaxis did not have damage to the left wrist, while 36% of those with short-term substitution had an association with moderate–severe damage to the left wrist (p = 0.014) (Table 5).

- -

- A total of 28% of patients with short-term substitution associated severe damage to the right elbow, while patients with continuous prophylaxis did not present damage to the right elbow (p = 0.025) (Table 5).

- -

- A total of 85.7% of patients with continuous prophylaxis did not have damage to the left elbow, while 60% of the patients with short-term substitution were associated with moderate–severe damage to the left elbow (p = 0.002) (Table 5).

- -

- A total of 85.7% of patients with continuous prophylaxis and 56% of patients with short-term substitution did not have an association with right shoulder damage (p = 0.147) (Table 5).

- -

- All of the patients with continuous prophylaxis and 68% of those with short-term substitution did not have an association with damage to the left shoulder (p = 0.098) (Table 5).

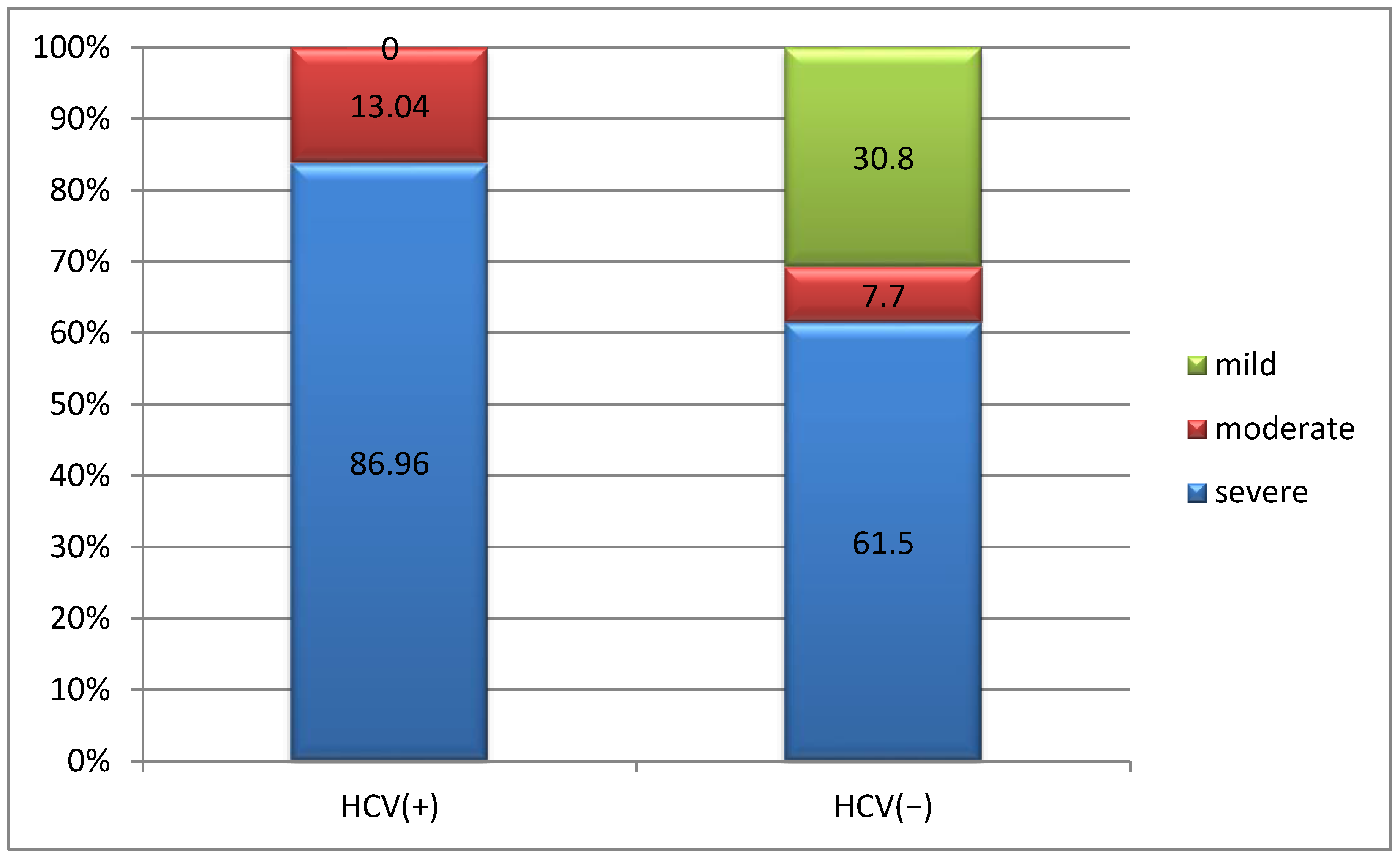

3.3. Comorbidities and Hemophilia

3.3.1. Correlation Between Form of Hemophilia and HCV Infection

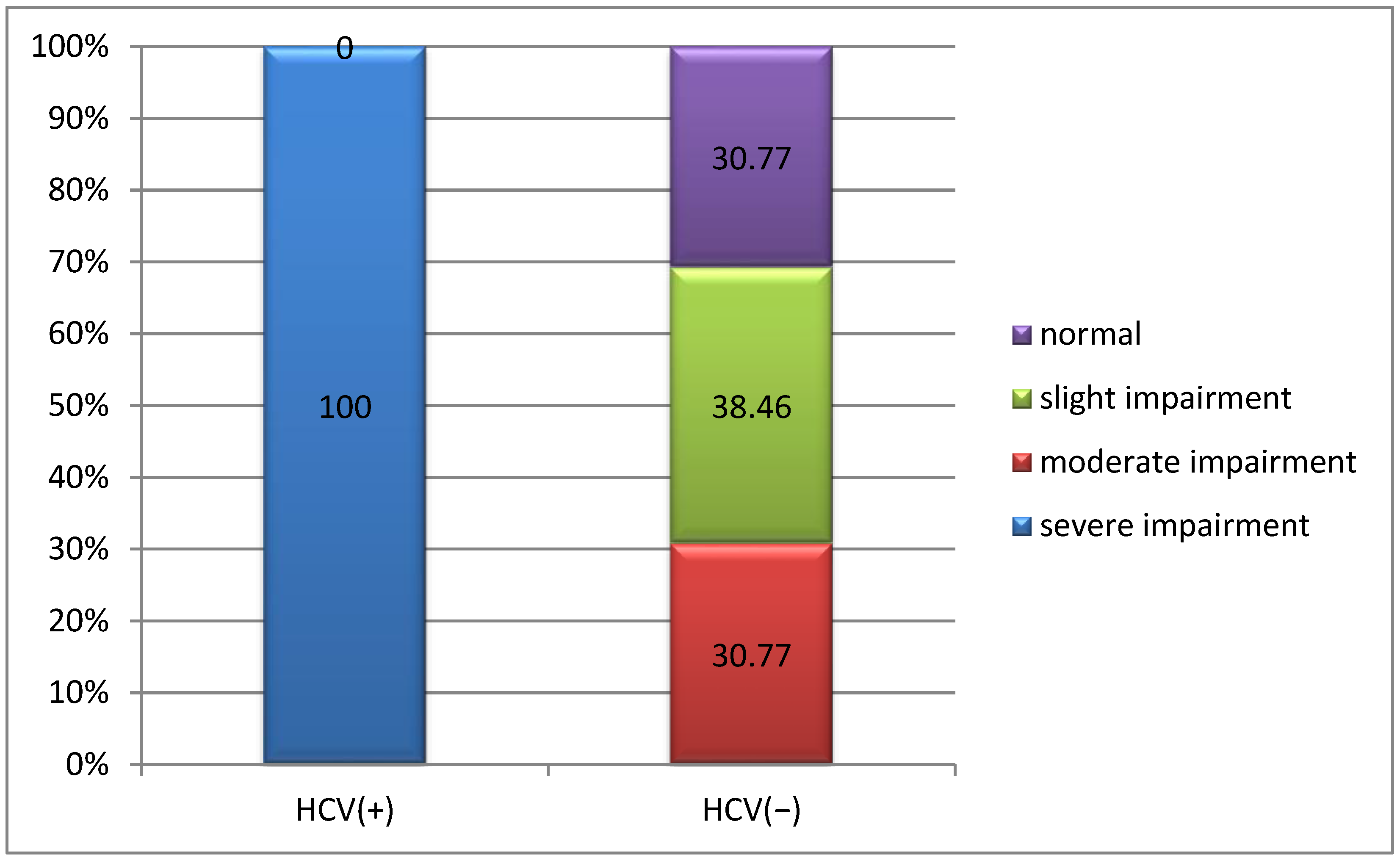

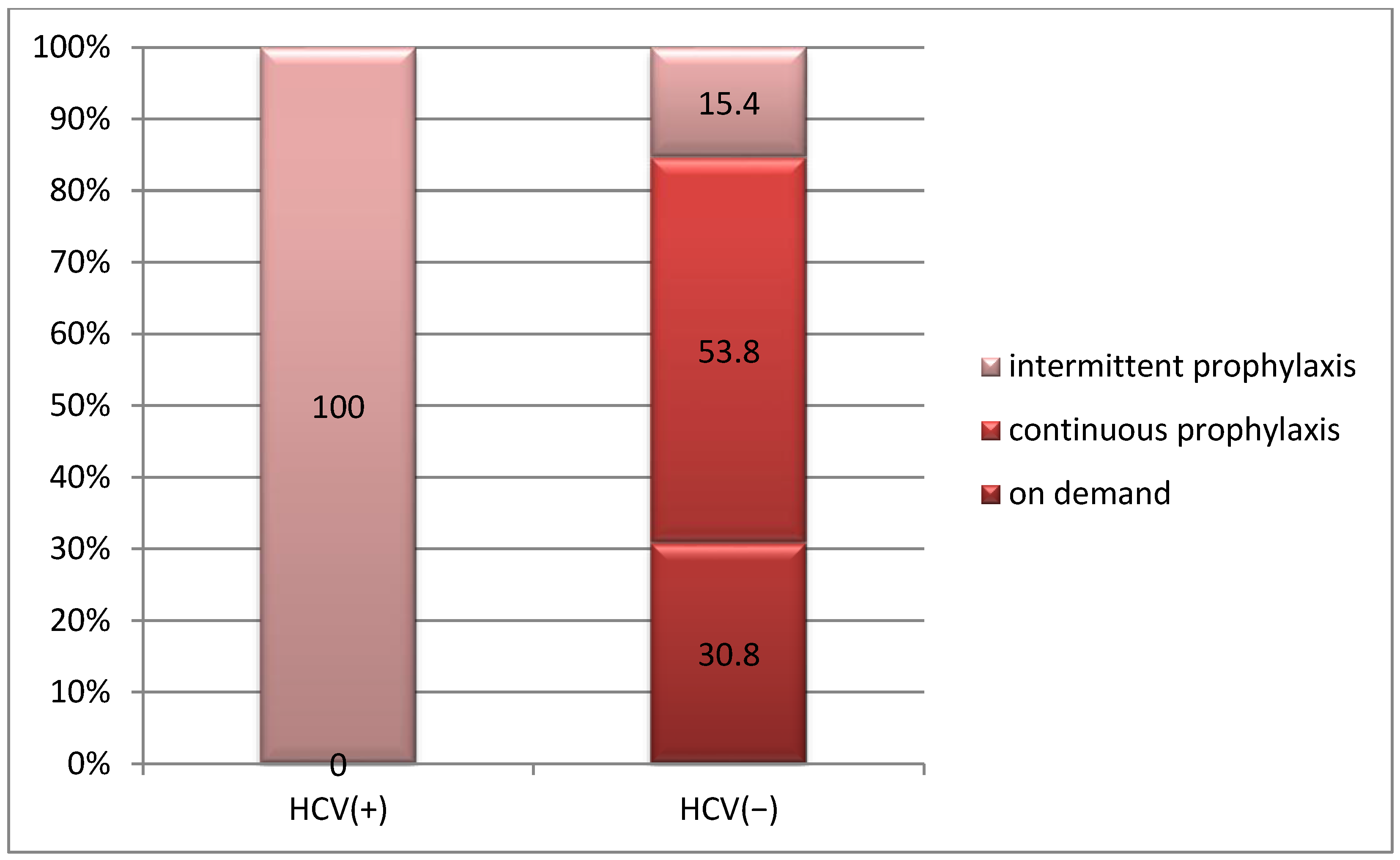

3.3.2. Correlation Between Joint Damage and HCV Infection

3.3.3. Correlation Between Treatment and HCV Infection

4. Discussion

4.1. The Clinical Implications of the Study

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Srivastava, A.; Santagostino, E.; Dougall, A.; Kitchen, S.; Sutherland, M.; Pipe, S.W.; Carcao, M.; Mahlangu, J.; Ragni, M.V.; Windyga, J.; et al. WFH Guidelines for the Management of Hemophilia, 3rd edition. Haemophilia 2020, 26 (Suppl. S6), 1–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Federation of Hemophilia. What Is Haemophilia? Available online: https://www1.wfh.org/publications/files/pdf-1324.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Den Uijl, I.E.M.; Fischer, K.; Van der Bom, J.G.; Grobbee, D.E.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Plug, I. Analysis of low frequency bleeding data: The association of joint bleeds according to baseline FVIII activity levels. Haemophilia 2011, 17, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Merchan, E. Hemophilic arthropathy: How to diagnose subclinical bleeding early and how to orthopedically treat a damaged joint. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2023, 16, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, J. Optimal treatment strategies for hemophilia: Achievements and limitations of current prophylactic regimens. Blood 2015, 125, 2038–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soucie, J.M.; Monahan, P.E.; Kulkarni, R.; Konkle, B.A.; Mazepa, M.A. US Hemophilia Treatment Center Network. The frequency of joint hemorrhages and procedures in nonsevere hemophilia A vs B. Blood Adv. 2018, 2, 2136–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tiede, A.; Abdul Karim, F.; Jiménez-Yuste, V.; Klamroth, R.; Lejniece, S.; Suzuki, T.; Growth, A.; Santagostino, E. Factor VIII activity and bleeding risk during prophylaxis for severe hemophilia A: A population pharmacokinetic model. Haematologica 2021, 106, 1902–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, V.S.; Key, N.S.; Ljung, L.R.; Manco-Johnson, M.J.; Van Den Berg, H.M.; Srivastava, A. Definitions in hemophilia: Communication from the SSC of the ISTH. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 1935–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; Reddivari, A.K.R. Hemophilia. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.D. Comorbidities of cardiovascular disease and cancer in hemophilia patients. Thromb. J. 2016, 14 (Suppl. S1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Galen, K.P.M.; d’Oiron, R.; James, P.; Abdul-Kadir, R.; Kouides, P.A.; Kulkarni, R.; Mahlangu, J.N.; Othman, M.; Peyvandi, F.; Rotellini, D.; et al. A new hemophilia carrier nomenclature to define hemophilia in women and girls: Communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannuci, P.M. Witnessing the 1980s. Haemophilia 2020, 26, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, P.; Boukouvala, A.; McDaniel, J.; Nance, D. Hemophilia A in Females: Considerations for Clinical Management. Acta Haematol. 2020, 143, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntorp, E.; Hermans, C.; Solms, A.; Poulsen, L.; Mancuso, M.E. Optimising prophylaxis in haemophilia A: The ups and downs of treatment. Blood Rev. 2021, 50, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcao, M.; Lambert, T.; Leissinger, C.; Escuriola-Ettingshausen, C.; Santagostino, E.; Aledort, L. Prophylaxis re-visited: The potential impact of novel factor andnon-factor therapies on prophylaxis. Haemophilia 2018, 24, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Uijl, I.E.M.; Biesma, D.; Grobbee, D.; Fischer, K. Turning severe into moderate haemophilia by prophylaxis: Are we reaching our goal? Blood Transfus. 2013, 11, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manco-Johnson, M.J.; Lundin, B.; Funk, S.; Peterfy, C.; Raunig, D.; Werk, M.; Kempton, C.L.; Reding, M.T.; Goranov, S.; Gercheva, L.; et al. Effect of late prophylaxis in hemophilia on joint status: A randomized trial. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 15, 2115–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Merchan, E.C.; Jimenez-Yuste, V.; Aznar, J.A.; Hedner, U.; Knobe, K.; Lee, C.A.; Ljung, R.; Querol, F.; Santagostino, E.; Valentino, L.A.; et al. Joint protection in haemophilia. Haemophilia 2011, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; van der Bom, J.G.; Mauser-Bunschoten, E.P.; Roosendaal, G.; Beek, F.J.A.; de Kleijn, P.; Grobbee, D.E.; van den Berg, H.M. Endogenous clotting factor activity and long-term outcome in patients with moderate haemophilia. Thromb. Haemost. 2000, 84, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hmida, J.; Hilberg, T.; Ransmann, P.; Tomschi, F.; Klein, C.; Koob, S.; Franz, A.; Richter, H.; Oldenburg, J.; Strauss, A.C. Most subjectively affected joints in patients with haemophilia—What has changed after 20 years in Germany? Haemophilia. 2022, 28, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vulpen, L.F.D.; Holstein, K.; Martinoli, C. Joint disease in haemophilia: Pathophysiology, pain and imaging. Haemophilia 2018, 24 (Suppl. S6), 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtierotti, R.; Solimeno, L.P.; Peyvandi, F. Hemophilic arthropathy: Current knowledge and future perspectives. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 2112–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevgili, B.; Demirci, Z.; Tekin, F.; Saydam, G.; Şahin, F. MPN-149 Hemophilia and Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Beyond Hemarthrosis. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2023, 23 (Suppl. S1), S385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanik, A.B.; Zaleska, M.; Wiszniewski, A.; Wislawski, S.; Misiak, A.; Maryniak, R.; Windyga, J. Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with haemophilia in Poland: Prevalence and risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Haemophilia 2005, 11, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanoudaki, A.; Papadopoulos, N.; Trifylli, E.M.; Koustas, E.; Vasileiadi, S.; Deutsch, M. Hepatitis C Virus Infections in Patients with Hemophilia: Links, Risks and Management. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2022, 15, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blach, S.; Terrault, N.A.; Tacke, F.; Gamkrelidze, I.; Craxi, A.; Tanaka, J.; Waked, I.; Dore, G.J.; Abbas, Z.; Abdallah, A.R.; et al. Global change in hepatitis C virus prevalence and cascade of care between 2015 and 2020: A modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudot-Thoraval, F. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2021, 45, 101596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmer, N.M.; Sherman, K.E. Hepatitis C-related arthropathy: Diagnostic and treatment considerations. J. Musculoskelet. Med. 2010, 27, 351–354. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, A.M.; Al-Hnhna, A.A.; Al-Huraibi, B.S.; Assayaghi, R.M.; Al-Qahtani, T.Y.; Jahzar, K.H.; Al-Huthaifi, M.M. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus among patients with arthralgia: Is it logic for screening? Virol. J. 2023, 20, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzaro, C.; Quartuccio, L.; Adinolfi, L.E.; Roccatello, D.; Pozzato, G.; Nevola, R.; Tonizzo, M.; Gitto, S.; Andreone, P.; Gattei, V. A Review on Extrahepatic Manifestations of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection and the Impact of Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy. Viruses 2021, 13, 2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

|

Male

Female |

34

2 |

94.4

5.6 |

| Age | ||

|

<45 years old

≥45 years old |

17

19 |

47.2

52.8 |

| Urban vs. rural | ||

|

Urban

Rural |

15

21 |

41.7

58.3 |

| Type of hemophilia | ||

|

Type A

Type B |

30

6 |

83.3

16.7 |

| Forms of hemophilia | ||

|

Mild

Moderate Severe |

4

4 28 |

11.1

11.1 77.8 |

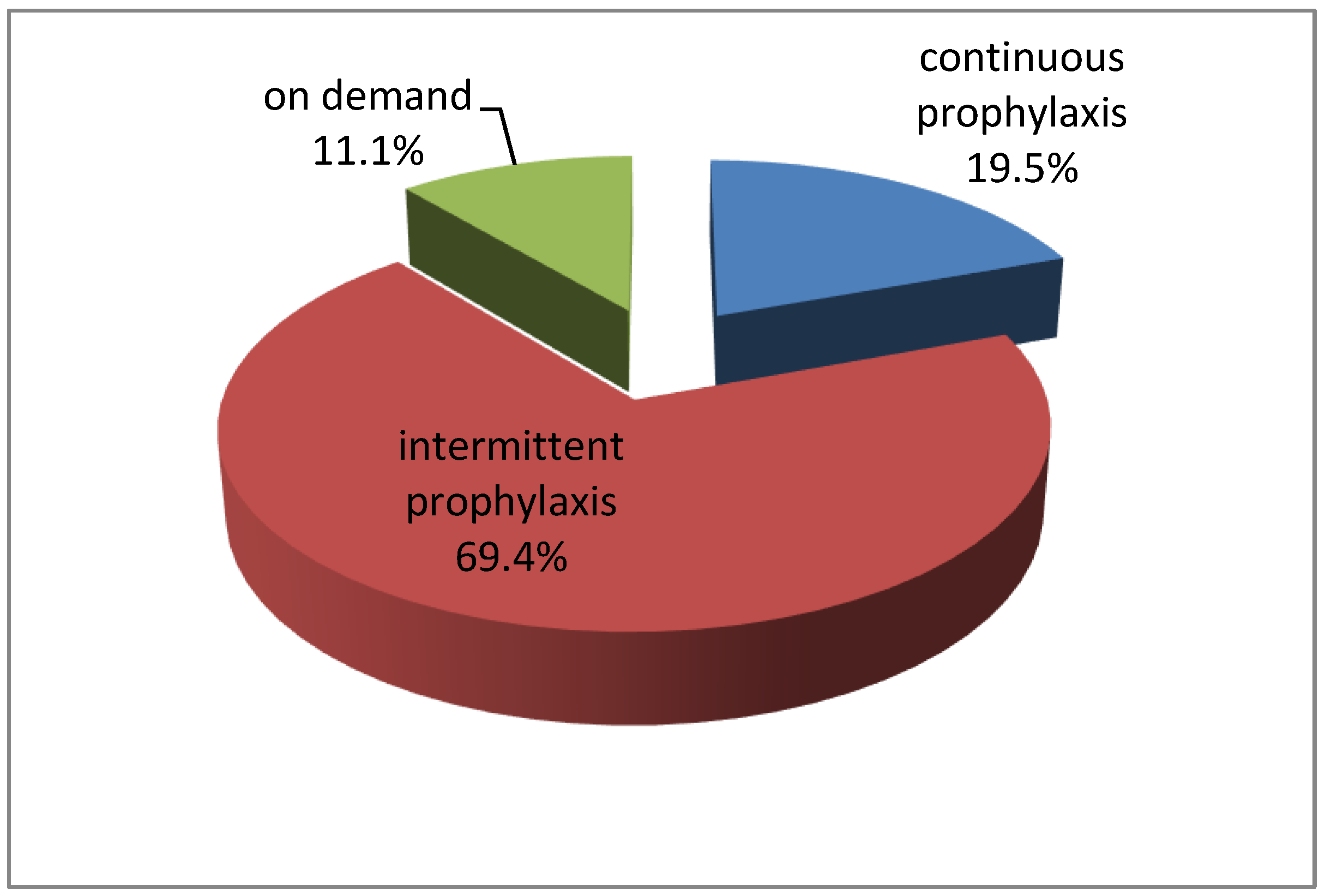

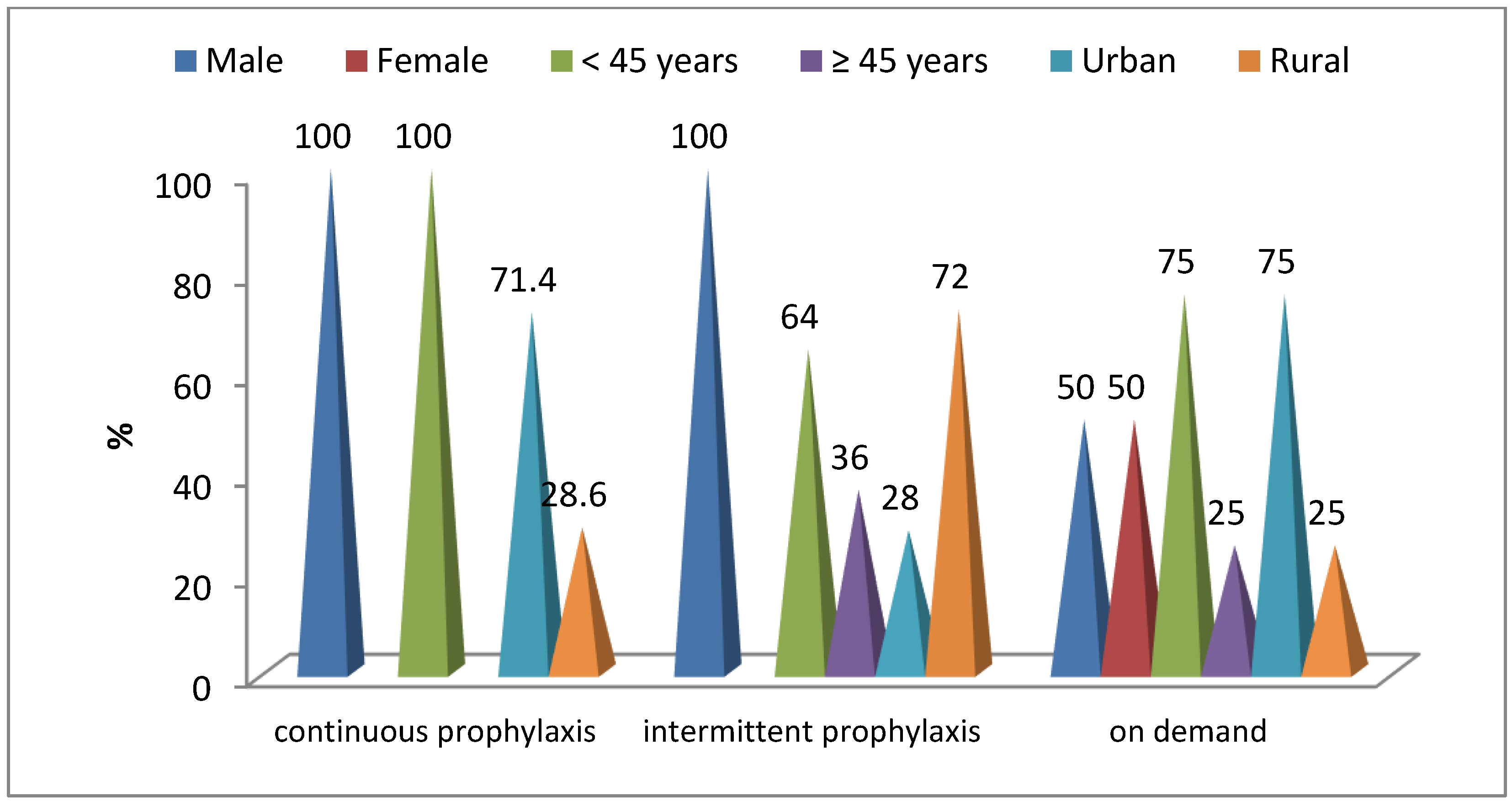

| Treatment | ||

|

On demand

Continuous prophylaxis Intermittent prophylaxis |

4

7 25 |

11.1

19.5 69.4 |

| Joint | Absent | Mild | Moderate | Severe | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right knee | 10 (27.8%) | 2 (5.6%) | 6 (16.7%) | 18 (50.0%) | 0.001 |

| Left knee | 12 (33.3%) | 4 (11.1%) | 8 (22.2%) | 12 (33.3%) | |

| Right ankle | 7 (19.4%) | 10 (27.8%) | 10 (27.8%) | 9 (25.0%) | 0.002 |

| Left ankle | 7 (19.4%) | 16 (44.4%) | 6 (16.7%) | 7 (19.4%) | |

| Right hip | 27 (75,0%) | 3 (8.3%) | 1 (2.8%) | 5 (13.9%) | 0.601 |

| Left hip | 25 (69.4%) | 4 (11.1%) | 2 (5.6%) | 5 (13.9%) | |

| Right wrist | 21 (58.3%) | 6 (16.7%) | 5 (13.9%) | 4 (11.1%) | 0.136 |

| Left wrist | 21 (58.3%) | 6 (16.7%) | 7 (19.4%) | 2 (5.6%) | |

| Right elbow | 13 (36.1%) | 6 (16.7%) | 10 (27.8%) | 7 (19.4%) | 0.809 |

| Left elbow | 14 (38.9%) | 7 (19.4%) | 9 (25.0%) | 6 (16.7%) | |

| Right shoulder | 24 (66.7%) | 3 (8.3%) | 6 (16.7%) | 3 (8.3%) | 0.296 |

| Left shoulder | 28 (77.8%) | 3 (8.3%) | 5 (13.9%) | - |

| Joint Score | Study | At Least 3 Joints Affected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | n | % | |

| Absent | 4 | 11.1 | ||

| Mild | 5 | 13.9 | 1 | 20.0 |

| Moderate | 4 | 11.1 | 1 | 25.0 |

| Severe | 23 | 63.9 | 13 | 56.5 |

| Joint Damage | Hemophilia A | Hemophilia B | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Right knee | 6.7% | 16.7% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 50.0% | 0.848 |

| Left knee | 10.0% | 26.7% | 36.7% | 16.4% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.050 |

| Right ankle | 16.7% | 30.0% | 30.0% | 83.3% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 0.007 |

| Left ankle | 36.7% | 20.0% | 23.3% | 83.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.048 |

| Right hip | 10.0% | 3.3% | 13.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.668 |

| Left hip | 10.0% | 6.7% | 13.3% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.812 |

| Right wrist | 20.0% | 13.3% | 13.3% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 0.223 |

| Left wrist | 20.0% | 20.0% | 6.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.302 |

| Right elbow | 16.7% | 30.0% | 23.3% | 16.7% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 0.214 |

| Left elbow | 13.3% | 30.0% | 20.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.040 |

| Right shoulder | 10.0% | 16.7% | 10.0% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 0.481 |

| Left shoulder | 10.0% | 13.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 16.7% | 0.0% | 0.560 |

| Joint Damage | Treatment | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Prophylaxis | Intermittent Prophylaxis | ||||||

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Right knee | 14.3% | 28.6% | 0.0% | 4.0% | 16.0% | 72.0% | 0.001 |

| Left knee | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.0% | 32.0% | 48.0% | 0.001 |

| Right ankle | 42.9% | 28.6% | 0.0% | 28.0% | 32.0% | 36.0% | 0.050 |

| Left ankle | 36.7% | 20.0% | 23.3% | 83.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.019 |

| Right hip | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.0% | 4.0% | 20.0% | 0.148 |

| Left hip | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 16.0% | 8.0% | 20.0% | 0.076 |

| Right wrist | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 24.0% | 20.0% | 16.0% | 0.014 |

| Left wrist | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 24.0% | 28.0% | 8.0% | 0.014 |

| Right elbow | 14.3% | 14.3% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 36.0% | 28.0% | 0.025 |

| Left elbow | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 24.0% | 36.0% | 24.0% | 0.002 |

| Right shoulder | 14.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 8.0% | 24.0% | 12.0% | 0.147 |

| Left shoulder | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 12.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.098 |

| Comorbidities | Hemophilia A (n = 30) | Hemophilia B (n = 6) | Chi2 Test p | RR | IC95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| HCV infection | 20 | 66.7 | 3 | 50.0 | 0.369 | 1.77 A | 0.42–7.53 |

| Arterial hypertension | 8 | 26.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.193 | 1.27 A | 1.05–1.54 |

| Ischemic cardiac disease | 5 | 16.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.378 | 1.24 A | 1.04–1.47 |

| Obesity | 5 | 16.7 | 2 | 33.3 | 0.329 | 1.21 B | 0.74–1.97 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 2 | 6.7 | 2 | 33.3 | 0.048 | 7.00 B | 0.76–6.46 |

| Others | 4 | 13.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.465 | 1.23 A | 1.04–1.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarniceriu, C.C.; Hurjui, L.L.; Tanase, D.M.; Haisan, A.; Tepordei, R.T.; Statescu, G.; Vicoleanu, S.A.P.; Lupu, A.; Lupu, V.V.; Ursaru, M.; et al. Inherited Hemophilia—A Multidimensional Chronic Disease That Requires a Multidisciplinary Approach. Life 2025, 15, 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15040530

Tarniceriu CC, Hurjui LL, Tanase DM, Haisan A, Tepordei RT, Statescu G, Vicoleanu SAP, Lupu A, Lupu VV, Ursaru M, et al. Inherited Hemophilia—A Multidimensional Chronic Disease That Requires a Multidisciplinary Approach. Life. 2025; 15(4):530. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15040530

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarniceriu, Cristina Claudia, Loredana Liliana Hurjui, Daniela Maria Tanase, Anca Haisan, Razvan Tudor Tepordei, Gabriel Statescu, Simona Alice Partene Vicoleanu, Ancuta Lupu, Vasile Valeriu Lupu, Manuela Ursaru, and et al. 2025. "Inherited Hemophilia—A Multidimensional Chronic Disease That Requires a Multidisciplinary Approach" Life 15, no. 4: 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15040530

APA StyleTarniceriu, C. C., Hurjui, L. L., Tanase, D. M., Haisan, A., Tepordei, R. T., Statescu, G., Vicoleanu, S. A. P., Lupu, A., Lupu, V. V., Ursaru, M., & Nedelcu, A. H. (2025). Inherited Hemophilia—A Multidimensional Chronic Disease That Requires a Multidisciplinary Approach. Life, 15(4), 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15040530