Adjuvant Tegafur-Uracil Improves Survival in Low-Risk, Mismatch Repair Proficient Stage IIA Colon Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

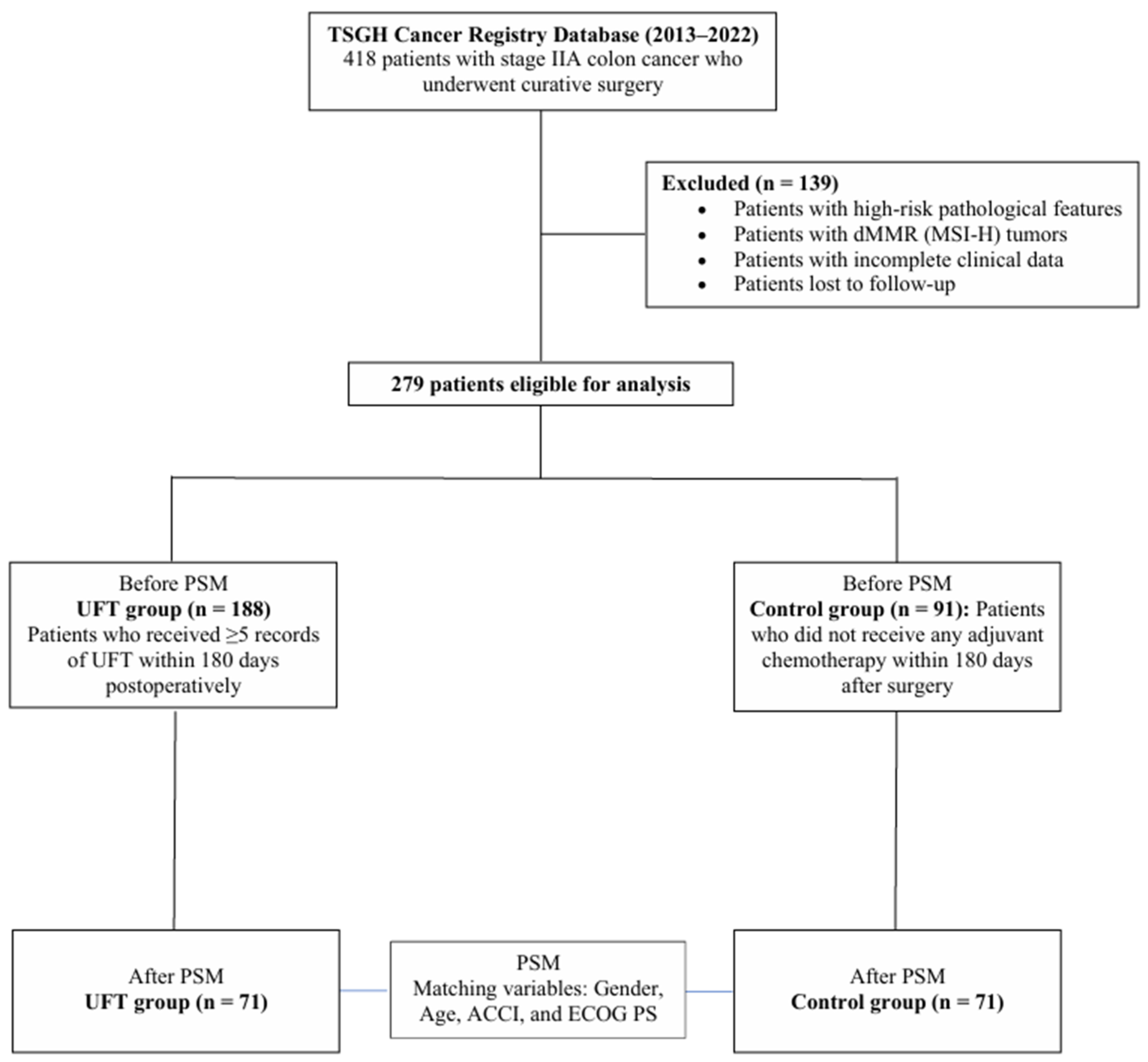

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Cohort Definition and Covariates

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Propensity Score Matching

2.5. Outcome Analyses

2.6. Sensitivity Analyses

2.7. Subgroup Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Propensity Score Matching

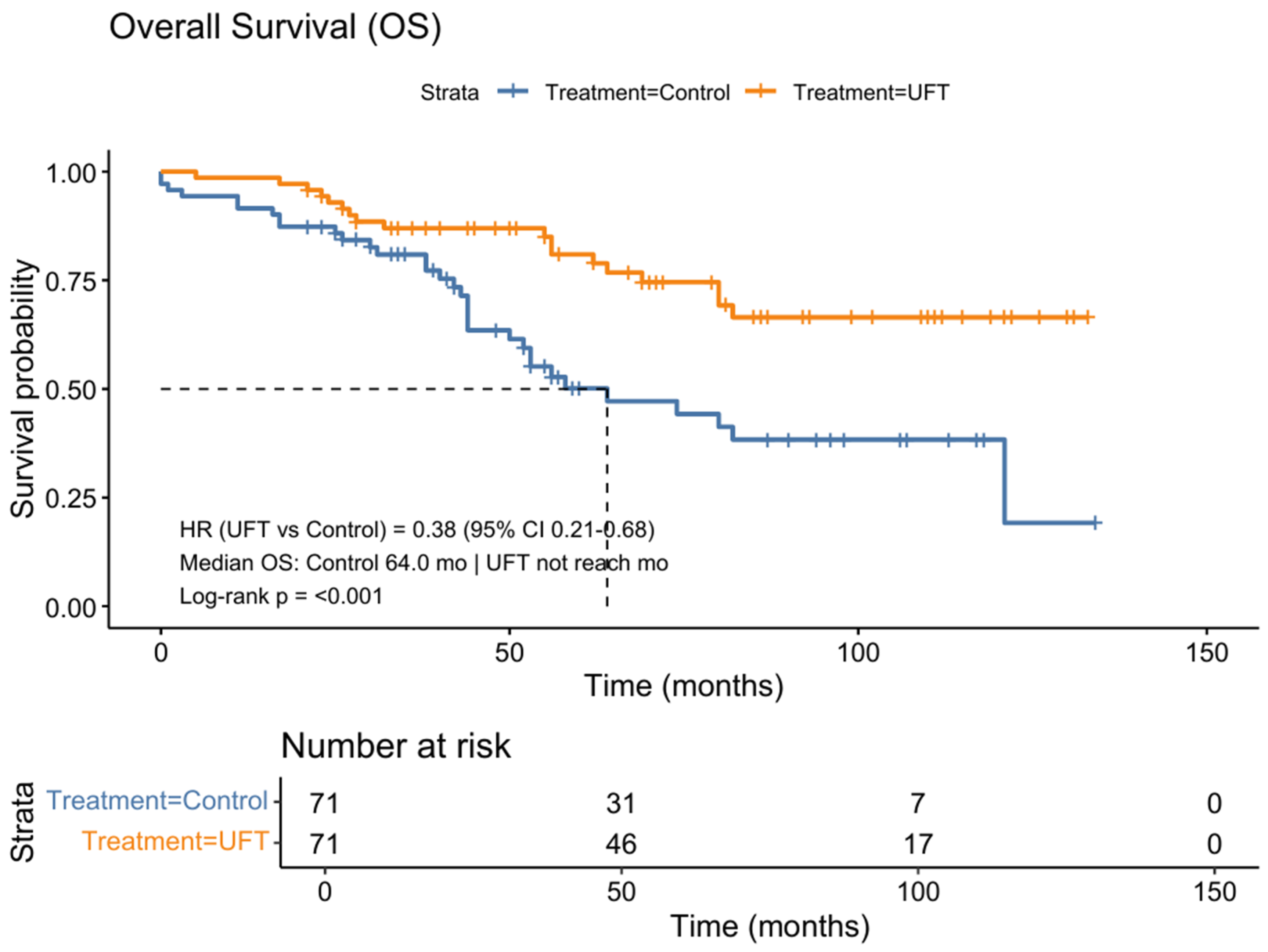

3.2. Survival Outcomes in the Matched Cohort

3.3. Prognostic Factors and Sensitivity Analyses

3.4. Subgroup-Specific Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACCI | Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index |

| ECOG PS | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status |

| ICD | International Classification of Diseases |

| MSS | Microsatellite-stable |

| PSM | Propensity Score Matching |

| pMMR | Mismatch repair proficient |

| UFT | Tegafur-uracil |

References

- Taieb, J.; Karoui, M.; Basile, D. How I Treat Stage II Colon Cancer Patients. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, N.N.; Kennedy, E.B.; Bergsland, E.; Berlin, J.; George, T.J.; Gill, S.; Gold, P.J.; Hantel, A.; Jones, L.; Lieu, C.; et al. Adjuvant Therapy for Stage II Colon Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 892–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikas, P.; Messersmith, H.; Compton, C.; Sholl, L.; Broaddus, R.R.; Davis, A.; Estevez-Diz, M.; Garje, R.; Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; Leiser, A.; et al. Mismatch Repair and Microsatellite Instability Testing for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Endorsement of College of American Pathologists Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1943–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, A.N.; Mills, A.M.; Konnick, E.; Overman, M.; Ventura, C.B.; Souter, L.; Colasacco, C.; Stadler, Z.K.; Kerr, S.; Howitt, B.E.; et al. Mismatch Repair and Microsatellite Instability Testing for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: Guideline from the College of American Pathologists in Collaboration with the Association for Molecular Pathology and Fight Colorectal Cancer. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2022, 146, 1194–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.D.; Li, T.; Hsieh, M.-C.; Yi, Y.; Gibbs, J.F.; Sahawneh, J.; Sang, W.; Gallagher, J.; Wu, X.-C. Survival Paradox between Stage IIB/C and Stage IIIA Colon Cancer: Is It Time to Revise the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM System? Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 2857–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hua, R.; He, J.; Zhang, H. Survival Contradiction in Stage II, IIIA, And IIIB Colon Cancer: A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result-Based Analysis. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 4088117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-L.; Chen, P.-H.; Lee, H.-L.; Jhou, H.-J.; Lee, C.-H.; Lee, J.-C.; Chu, Y.-H.; Chen, J.-H. Tegafur-Uracil as a Maintenance Therapy for Non-Metastatic Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: Insights from the Literature. Anticancer Res. 2025, 45, 3617–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-L.; Chen, P.-H.; Huang, T.-C.; Ye, R.-H.; Chu, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-C.; Jhou, H.-J.; Chen, J.-H. Tegafur-Uracil Maintenance Therapy in Non-Metastatic Head and Neck Cancer: An Exploratory Systematic Review. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-H.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Lee, C.-H.; Chung, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-G.; Huang, T.-C.; Yeh, R.-H.; Chang, P.-Y.; Dai, M.-S.; Lai, S.-W.; et al. Uracil-Tegafur vs Fluorouracil as Postoperative Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage II and III Colon Cancer. Medicine 2021, 100, e25756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-H.; Jhou, H.-J.; Chung, C.-H.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Huang, T.-C.; Lee, C.-H.; Chien, W.-C.; Chen, J.-H. Benefit of Uracil-Tegafur Used as a Postoperative Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage IIA Colon Cancer. Medicina 2022, 59, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.J.; You, S.L.; Chen, C.J.; Yang, Y.W.; Lo, W.C.; Lai, M.S. Quality assessment and improvement of nationwide cancer registration system in Taiwan: A review. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 45, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.-W.; Chiang, C.-J.; Lin, L.-J.; Huang, C.-W.; Lee, W.-C.; Lee, M.-Y.; Cheng-Yi, S.; Lin, H.-L.; Lin, M.-M.; Wang, Y.-P.; et al. Accuracy of long-form data in the Taiwan cancer registry. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2021, 120, 2006–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.-J.; Wang, Y.-W.; Lee, W.-C. Taiwan’s Nationwide Cancer Registry System of 40 years: Past, present, and future. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118, 856–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.-Y.; Chen, W.-L.; Wu, W.-T.; Wang, C.-C. Return to Work and Mortality in Breast Cancer Survivors: An 11-Year Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundararajan, V.; Henderson, T.; Perry, C.; Muggivan, A.; Quan, H.; Ghali, W.A. New ICD-10 Version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index Predicted in-Hospital Mortality. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2004, 57, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S.-W.; Su, Y.-C.; Pallantla, R.; Channavazzala, M.; Kumar, R.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Tse, A. Can a Propensity Score Matching Method Be Applied to Assessing Efficacy from Single-Arm Proof-of-Concept Trials in Oncology? CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 1347–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.T.; Chung, K.C. The Use of the E-Value for Sensitivity Analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2023, 163, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckelman, C.; Engelmann, B.E.; Kaprio, T.; Hansen, T.F.; Glimelius, B. Risk of Recurrence in Patients with Colon Cancer Stage II and III: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Literature. Acta Oncol. 2015, 54, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, C.; Ishiguro, M.; Teramukai, S.; Kajiwara, Y.; Fujii, S.; Kinugasa, Y.; Nakamoto, Y.; Kotake, M.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kurachi, K.; et al. A Randomised-Controlled Trial of 1-Year Adjuvant Chemotherapy with Oral Tegafur-Uracil Versus Surgery Alone in Stage II Colon Cancer: SACURA Trial. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 96, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Ishiguro, M.; Nakatani, E.; Ishikawa, T.; Uetake, H.; Matsuda, C.; Nakamoto, Y.; Kotake, M.; Kurachi, K.; Egawa, T.; et al. Prospective Multicenter Study on the Prognostic and Predictive Impact of Tumor Budding in Stage II Colon Cancer: Results from the SACURA Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1886–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebuzzi, S.E.; Pesola, G.; Martelli, V.; Sobrero, A.F. Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage II Colon Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribic, C.M.; Sargent, D.J.; Moore, M.J.; Thibodeau, S.N.; French, A.J.; Goldberg, R.M.; Hamilton, S.R.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Gryfe, R.; Shepherd, L.E.; et al. Tumor Microsatellite-Instability Status as a Predictor of Benefit from Fluorouracil-Based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.C.-H.; Lien, M.-Y.; Chang, P.-H.; Wang, H.-M.; Yeh, K.-Y.; Ho, C.-L.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Hsieh, M.-C.; Chen, J.-H. UFUR Maintenance Therapy Significantly Improves Survival in Locally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Following Definitive Chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.R.; Kim, H.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Park, I.J.; Lim, S.-B.; Yu, C.S.; Kim, J.C. Effectiveness of Oral Fluoropyrimidine Monotherapy as Adjuvant Chemotherapy for High-Risk Stage II Colon Cancer. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2022, 102, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadahiro, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Tsuchiya, T.; Takahashi, T.; Ohge, H.; Sato, T.; Kondo, K.; Ogata, Y.; Baba, H.; Itabashi, M.; et al. Prospective Observational Study of the Efficacy of Oral Uracil and Tegafur plus Leucovorin for Stage II Colon Cancer with Risk Factors for Recurrence Using Propensity Score Matching (JFMC46-1201). BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, Y.; Taniguchi, H.; Uetake, H.; Ishiguro, M.; Matsuda, C.; Nakamoto, Y.; Kotake, M. Final Analyses of the Prospective Controlled Trial on the Efficacy of Uracil–Tegafur/Leucovorin as Adjuvant Treatment for Stage II Colon Cancer with Risk Factors for Recurrence Using Propensity Score-Based Methods (JFMC46-1201). Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 29, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-L.; Tseng, W.-K.; Liao, C.-K.; Yeh, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-H.; Liu, Y.-H.; Lin, T.-L. Using Oral Tegafur/Uracil (UFT) Plus Leucovorin as Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage II Colorectal Cancer: A Propensity Score Matching Study from Taiwan. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaster, T.; Eggertsen, C.M.; Støvring, H.; Ehrenstein, V.; Petersen, I. Quantifying the Impact of Unmeasured Confounding in Observational Studies with the E Value. BMJ Med. 2023, 2, e000366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taieb, J.; Gandini, A.; Seligmann, J.F.; Gallois, C. The Clinical Dilemma of High-Risk Stage II Colon Cancer: Are We Truly Prepared to Withdraw Oxaliplatin? ESMO Open 2024, 9, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argilés, G.; Tabernero, J.; Labianca, R.; Hochhauser, D.; Salazar, R.; Iveson, T.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Quirke, P.; Yoshino, T.; Taieb, J.; et al. Localised Colon Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Level | Control (n = 91) | UFT (n = 188) | p-Value | SMD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female/Male | 44 (48.4%)/47 (51.6%) | 91 (48.4%)/97 (51.6%) | 0.993 | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 76.27 ± 12.31 | 66.99 ± 11.76 | <0.001 | −0.771 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.00 ± 3.59 Median (IQR) † 23.44 (22.67–24.59) | 23.64 ± 2.86 Median (IQR) † 23.44 (22.34–24.25) | 0.734 | 0.050 | |

| ACCI (Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index) | 6.07 ± 3.73 | 3.96 ± 2.55 | <0.001 | −0.660 | |

| ECOG PS (0–4) | 0/1/2/3/4 | 33 (36.3%)/37 (40.7%)/13 (14.3%)/6 (6.6%)/2 (2.2%) | 112 (59.6%)/57 (30.3%)/17 (9.0%)/2 (1.1%)/0 (0.0%) | <0.001 # | 0.687 |

| Tumor side | Left/Right | 32 (35.2%)/59 (64.8%) | 93 (49.5%)/95 (50.5%) | 0.024 | 0.407 |

| Histology | Adenocarcinoma/Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 86 (94.5%)/5 (5.5%) | 184 (97.9%)/4 (2.1%) | 0.157 # | 0.269 |

| Differentiation | Moderately/Well differentiated | 85 (93.4%)/6 (6.6%) | 168 (89.4%)/20 (10.6%) | 0.276 | 0.197 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 61.35 ± 101.52 Median (IQR) † 48.50 (35.25–59.75) | 61.27 ± 121.19 Median (IQR) † 42.00 (32.00–55.00) | 0.995 | −0.001 | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 8.12 ± 13.71 | 8.21 ± 17.69 | 0.970 | 0.006 | |

| RAS mutation | Wild-type/Mutant | 58 (65.2%)/31 (34.8%) | 125 (66.5%)/63 (33.5%) | 0.828 | 0.039 |

| BRAF mutation | Wild-type/Mutant | 91 (100.0%)/0 (0.0%) | 184 (97.9%)/4 (2.1%) | — | 0.253 |

| UFT dose (mg/day) [UFT group only] | 100/200/300/400/600 | 3 (1.6%)/18 (9.6%)/40 (21.3%)/123 (65.4%)/4 (2.1%) | |||

| UFT maintenance time (months) [UFT group only] | 17.25 ± 8.28 |

| Variable | Level | Control (n = 71) | UFT (n = 71) | p-Value | SMD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female/Male | 34 (47.9%)/37 (52.1%) | 36 (50.7%)/35 (49.3%) | 0.737 | 0.080 |

| Age (years) | 73.87 ± 12.79 | 72.41 ± 14.38 | 0.523 | −0.107 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.20 ± 3.79 Median (IQR) † 23.40 (23.40–24.75) | 23.38 ± 2.86 Median (IQR) † 23.40 (22.70–24.05) | 0.572 | 0.095 | |

| ACCI (Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index) | 5.30 ± 3.38 | 4.99 ± 3.10 | 0.570 | −0.096 | |

| ECOG PS (0–3) | 0/1/2/3 | 32 (45.1%)/25 (35.2%)/9 (12.7%)/5 (7.0%) | 28 (39.4%)/32 (45.1%)/9 (12.7%)/2 (2.8%) | 0.513 # | 0.303 |

| Tumor side | Left/Right | 22 (31.0%)/49 (69.0%) | 30 (42.3%)/41 (57.7%) | 0.163 | 0.331 |

| Histology | Adenocarcinoma/Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 67 (94.4%)/4 (5.6%) | 68 (95.8%)/3 (4.2%) | 1.000 # | 0.092 |

| Differentiation | Moderately/Well differentiated | 65 (91.5%)/6 (8.5%) | 59 (83.1%)/12 (16.9%) | 0.130 | 0.359 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 61.75 ± 114.60 Median (IQR) † 45.00 (35.00–55.75) | 58.39 ± 113.83 Median (IQR) † 44.00 (35.00–52.50) | 0.861 | −0.029 | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 8.56 ± 14.18 | 10.41 ± 18.35 | 0.525 | 0.113 | |

| RAS mutation | Wild-type/Mutant | 47 (68.1%)/22 (31.9%) | 43 (60.6%)/28 (39.4%) | 0.351 | 0.223 |

| BRAF mutation | Wild-type/Mutant | 71 (100.0%)/0 (0.0%) | 70 (98.6%)/1 (1.4%) | — | 0.238 |

| UFT dose (mg/day) [UFT group only] | 200/300/400/600 | NA | 8 (11.3%)/15 (21.1%)/47 (66.2%)/1 (1.4%) | ||

| UFT maintenance time (months) [UFT group only] | NA | 15.72 ± 8.65 |

| Variable | DFS HR (95% CI) | p-Value | OS HR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFT maintenance | 0.43 (0.25–0.75) | 0.003 | 0.38 (0.21–0.68) | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | <0.001 |

| Gender | 1.32 (0.78–2.25) | 0.304 | 1.20 (0.69–2.08) | 0.521 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 0.74 | 0.99 (0.92–1.06) | 0.668 |

| ACCI | 1.20 (1.12–1.28) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.12–1.30) | <0.001 |

| ECOG PS | ||||

| ECOG PS (1 vs. 0) | 1.78 (0.91–3.47) | 0.09 | 1.89 (0.96–3.74) | 0.066 |

| ECOG PS (2 vs. 0) | 3.55 (1.58–7.99) | 0.002 | 2.71 (1.19–6.21) | 0.018 |

| ECOG PS (3 vs. 0) | 6.30 (2.20–18.03) | 0.001 | 6.81 (2.36–19.65) | <0.001 |

| Tumor side (Right vs. Left) | 0.88 (0.51–1.51) | 0.64 | 0.76 (0.43–1.33) | 0.333 |

| Histology (Mucinous vs. Adenocarcinoma) | 2.59 (1.03–6.52) | 0.044 | 3.28 (1.29–8.32) | 0.012 |

| Differentiation (Well vs. Moderate differentiated) | 0.47 (0.19–1.18) | 0.109 | 0.44 (0.16–1.22) | 0.113 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.056 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.107 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.239 | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.214 |

| RAS mutation | 1.28 (0.73–2.23) | 0.394 | 1.30 (0.73–2.32) | 0.371 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, M.-C.; Lee, H.-L.; Lai, S.-W.; Chen, J.-H.; Chen, P.-H. Adjuvant Tegafur-Uracil Improves Survival in Low-Risk, Mismatch Repair Proficient Stage IIA Colon Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Life 2025, 15, 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121930

Cheng M-C, Lee H-L, Lai S-W, Chen J-H, Chen P-H. Adjuvant Tegafur-Uracil Improves Survival in Low-Risk, Mismatch Repair Proficient Stage IIA Colon Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Life. 2025; 15(12):1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121930

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Min-Chi, Hsu-Lin Lee, Shiue-Wei Lai, Jia-Hong Chen, and Po-Huang Chen. 2025. "Adjuvant Tegafur-Uracil Improves Survival in Low-Risk, Mismatch Repair Proficient Stage IIA Colon Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis" Life 15, no. 12: 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121930

APA StyleCheng, M.-C., Lee, H.-L., Lai, S.-W., Chen, J.-H., & Chen, P.-H. (2025). Adjuvant Tegafur-Uracil Improves Survival in Low-Risk, Mismatch Repair Proficient Stage IIA Colon Cancer: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Life, 15(12), 1930. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121930