Rising Global Temperatures and Kidney Health: A Comprehensive Review of Current Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Heat Stress and Renal Involvement

2.1. Heat Stress and Proteinuria

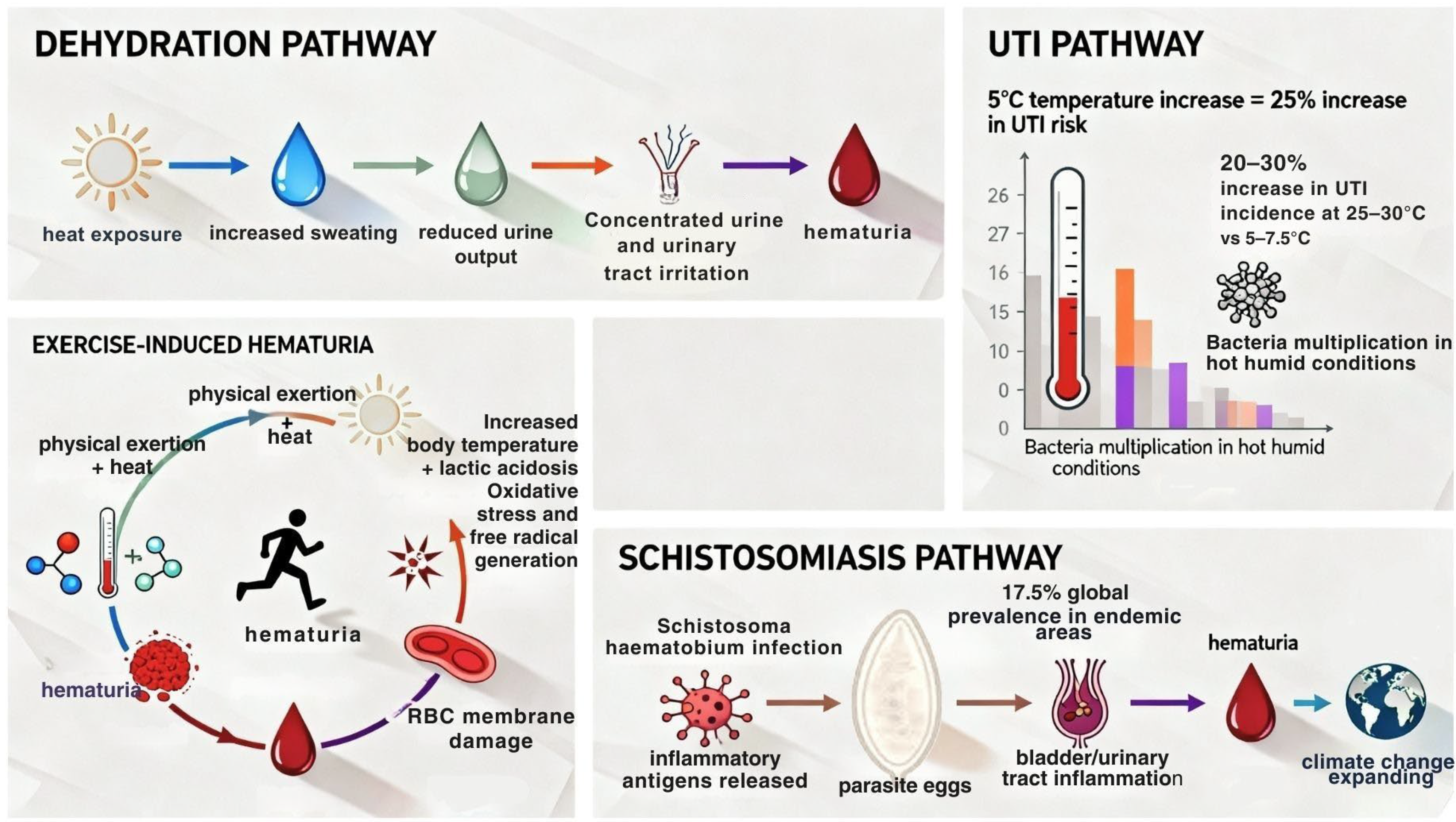

2.2. Heat Stress and Hematuria

2.3. Heat Stress and Nephrolithiasis

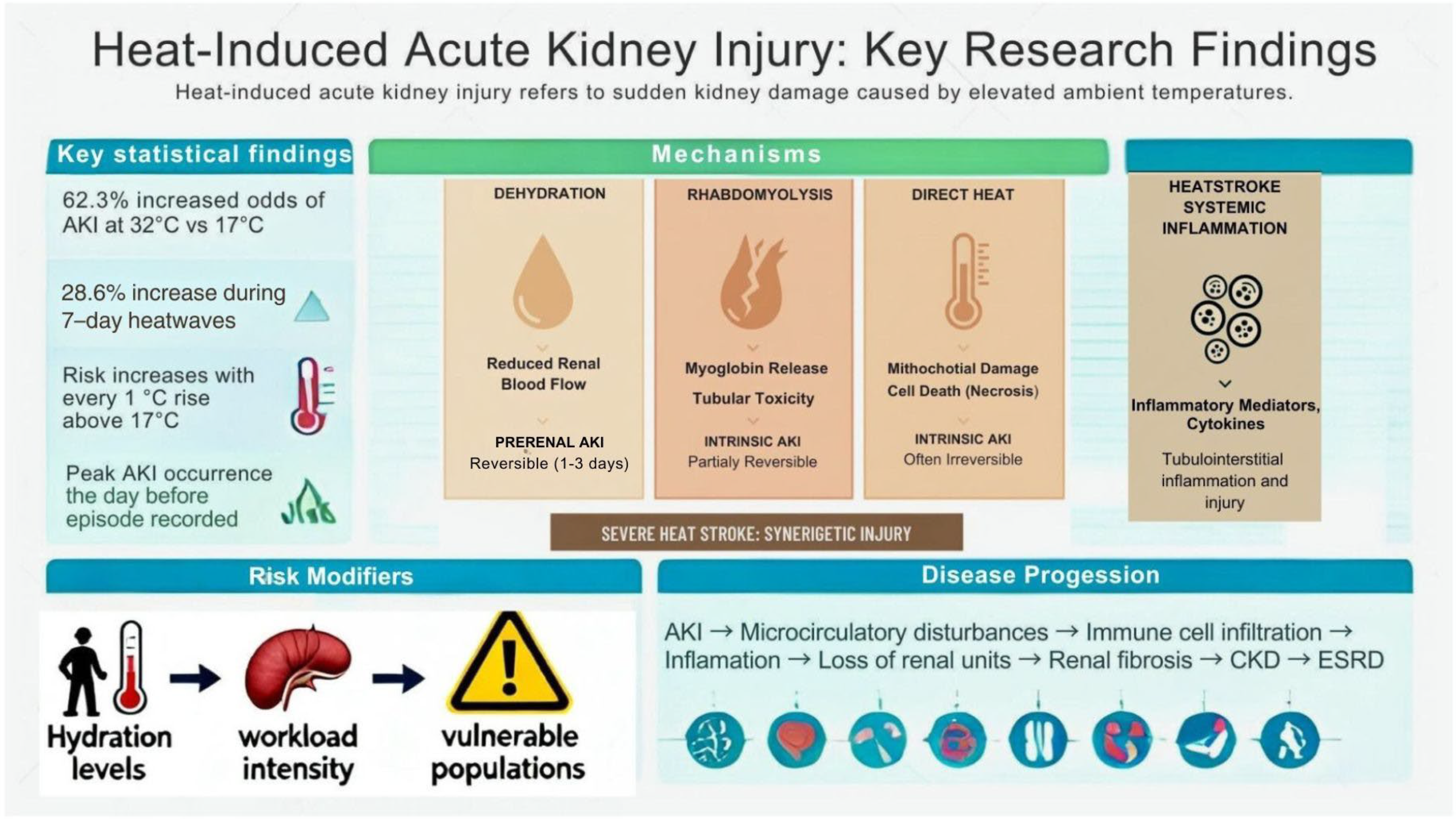

2.4. Heat Stress and AKI

2.5. Heat Stress and CKD

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dore, M.H.I. Climate change and changes in global precipitation patterns: What do we know? Environ. Int. 2005, 31, 1167–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebi, K.L.; Vanos, J.; Baldwin, J.W.; Bell, J.E.; Hondula, D.M.; Errett, N.A.; Hayes, K.; Reid, C.E.; Saha, S.; Spector, J.; et al. Extreme Weather and Climate Change: Population health and health system implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parums, D.V. A review of the increasing global impact of climate change on human health and approaches to medical preparedness. Med. Sci. Monit. 2024, 30, e945763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Guo, Y.; Ye, T.; Gasparrini, A.; Tong, S.; Overcenco, A.; Urban, A.; Schneider, A.; Entezari, A.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of mortality associated with non-optimal ambient temperatures from 2000 to 2019: A three-stage modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e415–e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marengo, J.A.; Costa, M.C.; Cunha, A.P.; Espinoza, J.-C.; Jimenez, J.C.; Libonati, R.; Miranda, V.; Trigo, I.F.; Sierra, J.P.; Geirinhas, J.L.; et al. Climatological patterns of heatwaves during winter and spring 2023 and trends for the period 1979–2023 in central South America. Front. Clim. 2025, 7, 1529082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.M.; Smith, C.; Walsh, T.; Lamb, W.F.; Lamboll, R.; Cassou, C.; Hauser, M.; Hausfather, Z.; Lee, J.-Y.; Palmer, M.D.; et al. Indicators of Global Climate Change 2024: Annual Update of Key Indicators of the State of the Climate System and Human Influence. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2025, 17, 2641–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus: 2024 is the First Year to Exceed 1.5 °C Above Pre-Industrial Level. Copernicus. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/copernicus-2024-first-year-exceed-15degc-above-pre-industrial-level (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Maslin, M.; Ramnath, R.D.; Welsh, G.I.; Sisodiya, S.M. Understanding the health impacts of the climate crisis. Future Healthc. J. 2025, 12, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Header, S. 2025 Heat Mortality Report; Environment & Health Data Portal: New York, NY, USA, 2025. Available online: https://a816-dohbesp.nyc.gov/IndicatorPublic/data-features/heat-report/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Matsee, W.; Charoensakulchai, S.; Khatib, A.N. Heat-related illnesses are an increasing threat for travellers to hot climate destinations. J. Travel Med. 2023, 30, taad072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehaj, L.; Kazancioğlu, R. The impact of climate change on chronic kidney disease. Bezmialem Sci. 2023, 11, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekara, T.D.K.S.C.; De Silva, P.M.C.S.; Chandana, E.P.S.; Jayasinghe, S.; Herath, C.; Siribaddana, S.; Jayasundara, N. Environmental heat exposure and implications on renal health of pediatric communities in the dry climatic zone of Sri Lanka: An approach with urinary biomarkers. Environ. Res. 2023, 222, 115399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, D.; Schlader, Z.J.; Jay, O. The Physiology behind the Epidemiology of Heat-Related Health Impacts. Physiology 2025, 41, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akerman, A.P.; Tipton, M.; Minson, C.T.; Cotter, J.D. Heat stress and dehydration in adapting for performance: Good, bad, both, or neither? Temperature 2016, 3, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, P.; Sahu, A.K.; Shristi, S.; Behera, T.K.; Sahoo, S.K.; Ahmed, S.N.; Mohanty, S.K.; Pati, S.S.; Murugesan, K.; Mallick, N.; et al. Heat Stress Nephropathy in CKD of Uncertain Etiology Hotspots of Bargarh District Odisha, India. Kidney Int. Rep. 2025, 10, 3379–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.T.T.; Tran, K.V.; Nguyen, T.D.; Pham, N.T.T.; Nguyen, T.H. Role of heat shock proteins in renal function and adaptation to heat stress: Implications for global warming. World J. Nephrol. 2025, 14, 107571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollmann, T.; McComb, E.C. Preliminary observations on a case of physiological albuminuria. J. Exp. Med. 1898, 3, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Roncal-Jimenez, C.A.; Andres-Hernando, A.; Jensen, T.; Tolan, D.R.; Sanchez-Lozada, L.G.; Newman, L.S.; Butler-Dawson, J.; Sorensen, C.; Glaser, J.; et al. Increase of core temperature affected the progression of kidney injury by repeated heat stress exposure. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2019, 317, F1111–F1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwag, Y. Long-Term Heat Exposure and Increased Risk of Proteinuria. In Abstracts of the 36th Annual Conference of the International Society for Environmental Epidemiology (ISEE); ISEE: Santiago, Chile, 2024; p. 112. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, C.L.; Johnson, B.D.; Parker, M.D.; Hostler, D.; Pryor, R.R.; Schlader, Z. Kidney physiology and pathophysiology during heat stress and the modification by exercise, dehydration, heat acclimation and aging. Temperature 2020, 8, 108–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebotareva, N.; Bobkova, I.; Shilov, E. Heat shock proteins and kidney disease: Perspectives of HSP therapy. Cell Stress Chaperones 2017, 22, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmering, J.E.; Polgreen, L.A.; Cavanaugh, J.E.; Erickson, B.A.; Suneja, M.; Polgreen, P.M. Warmer Weather and the Risk of Urinary Tract Infections in Women. J. Urol. 2020, 205, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarbanel, J.; Benet, A.E.; Lask, D.; Kimche, D. Sports Hematuria. J. Urol. 1990, 143, 887–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Deminice, R.; Ozdemir, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Bomkamp, M.P.; Hyatt, H. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Friend or foe? J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chala, B.; Torben, W. An epidemiological trend of urogenital schistosomiasis in Ethiopia. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams, M.; Khazaei, S.; Ghasemi, E.; Nazari, N.; Javanmardi, E.; Majidiani, H.; Bahadory, S.; Anvari, D.; Fatollahzadeh, M.; Nemati, T.; et al. Prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis of recently published literature (2016–2020). Trop. Med. Health 2022, 50, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, I.H.; Pourtois, J.D.; Chamberlin, A.J.; Mitchell, K.R.; Mari, L.; Lwiza, K.M.; Wood, C.L.; Mordecai, E.A.; Yu, A.; Tuan, R.; et al. Re-assessing thermal response of schistosomiasis transmission risk: Evidence for a higher thermal optimum than previously predicted. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2024, 18, e0011836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leo, G.A.; Stensgaard, A.-S.; Sokolow, S.H.; N’Goran, E.K.; Chamberlin, A.J.; Yang, G.-J.; Utzinger, J. Schistosomiasis and climate change. BMJ 2020, 371, m4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.-K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Li, W. The complex relationship between vitamin D and kidney stones: Balance, risks, and prevention strategies. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1435403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brikowski, T.H.; Lotan, Y.; Pearle, M.S. Climate-related increase in the prevalence of urolithiasis in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9841–9846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Tam, V.; Song, L.; Coffel, E.; Tasian, G. The impact of heat on kidney stone presentations in South Carolina under two climate change scenarios. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakheri, R.J.; Goldfarb, D.S. Ambient temperature as a contributor to kidney stone formation: Implications of global warming. Kidney Int. 2011, 79, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K. Weather and the incidence of urinary stone colic in Tokyo. Int. J. Biometeorol. 1987, 31, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K. Weather and the Incidence of Urinary Stone Colic. J. Urol. 1979, 121, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hadramy, M.S. Seasonal variations of urinary stone colic in Arabia. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 1997, 47, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Abreu Júnior, J.; Filho, S.R.F. Influence of climate on the number of hospitalizations for nephrolithiasis in urban regions in Brazil. Braz. J. Nephrol. 2020, 42, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soucie, J.M.; Thun, M.J.; Coates, R.J.; McClellan, W.; Austin, H. Demographic and geographic variability of kidney stones in the United States. Kidney Int. 1994, 46, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, K.B.; Conti, S.; Liao, J.C.; Sofer, M.; Pao, A.C.; Leppert, J.T.; Elliott, C.S. Redefining the Stone Belt: Precipitation Is Associated with Increased Risk of Urinary Stone Disease. J. Endourol. 2017, 31, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Xu, R.; Wu, Y.; De Sousa Zanotti Stagliorio Coêlho, M.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; Guo, Y.; Li, S. Association between ambient temperature and hospitalization for renal diseases in Brazil during 2000–2015: A nationwide case-crossover study. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2021, 6, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajat, S.; Casula, A.; Murage, P.; Omoyeni, D.; Gray, T.; Plummer, Z.; Steenkamp, R.; Nitsch, D. Ambient heat and acute kidney injury: Case-crossover analysis of 1 354 675 automated e-alert episodes linked to high-resolution climate data. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e156–e162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, A.; McKenna, Z.J.; Li, Z.; Deyhle, M.R.; Mermier, C.M.; Schlader, Z.J.; Amorim, F.T. Strategies to mitigate acute kidney injury risk during physical work in the heat. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2024, 326, F499–F510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butts, C.L. Dehydration, Muscle Damage, and Exercise in the Heat: Impacts on Renal Stress, Thermoregulation, and Muscular Damage Recovery. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR, USA, 2018. Available online: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2847/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Goto, H.; Kinoshita, M.; Oshima, N. Heatstroke-induced acute kidney injury and the innate immune system. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1250457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Shi, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Chen, K.; Zhang, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, G.; Liu, C. Extreme Heat Exposure Induced Acute Kidney Injury through NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Mice. Environ. Health 2024, 2, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z. Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategy of heat stroke-induced acute kidney injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 160, 114969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Périard, J.D.; DeGroot, D.; Jay, O. Exertional heat stroke in sport and the military: Epidemiology and mitigation. Exp. Physiol. 2022, 107, 1111–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junglee, N.A.; Di Felice, U.; Dolci, A.; Fortes, M.B.; Jibani, M.M.; Lemmey, A.B.; Walsh, N.P.; Macdonald, J.H. Exercising in a hot environment with muscle damage: Effects on acute kidney injury biomarkers and kidney function. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2013, 305, F813–F820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlader, Z.J.; Chapman, C.L.; Sarker, S.; Russo, L.; Rideout, T.C.; Parker, M.D.; Johnson, B.D.; Hostler, D. Firefighter work duration influences the extent of acute kidney injury. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 1745–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerbass, F.B.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Clark, W.F.; Sontrop, J.M.; McIntyre, C.W.; Moist, L. Occupational heat stress and kidney health: From farms to factories. Kidney Int. Rep. 2017, 2, 998–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonsalez, S.R.; Cortês, A.L.; Da Silva, R.C.; Lowe, J.; Prieto, M.C.; Da Silva Lara, L. Acute kidney injury overview: From basic findings to new prevention and therapy strategies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 200, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satirapoj, B.; Kongthaworn, S.; Choovichian, P.; Supasyndh, O. Electrolyte disturbances and risk factors of acute kidney injury patients receiving dialysis in exertional heat stroke. BMC Nephrol. 2016, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicas, R.C.; Wang, Y.; Weil, E.J.; Elon, L.; Xiuhtecutli, N.; Houser, M.C.; Jones, D.P.; Sands, J.M.; Hertzberg, V.; McCauley, L.; et al. The impact of heat exposures on biomarkers of AKI and plasma metabolome among agricultural and non-agricultural workers. Environ. Int. 2023, 180, 108206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Lv, C.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, H.; Lin, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, B. Transformation of acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease: The interaction between mitophagy and NLRP3 inflammasome. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1643829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Telagarapu, V.M.L.; Fornoni, A. Climate Change, Heat Stress, and Kidney Disease–Associated Mortality and Health Care Utilization. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9, 2844–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, J.; Wei, T.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; Ding, D.; Song, S. Temporal trends in cross-country inequalities of chronic kidney disease attributable to temperature exposure from 1990 to 2021. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2025, 57, 4209–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, I.R.; Bangera, A.; Nagaraju, S.P.; Shenoy, S.V.; Prabhu, R.A.; Rangaswamy, D.; Bhojaraja, M.V. Chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology: A comprehensive review of a global public health problem. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2023, 28, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, M.K. Chronic renal failure in India. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1993, 8, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazeyra, M.F.V.; Ramos, P.M.; Serrano, R.; Riaño, M.A.; Giraldo, Y.G.; Quiroga, B. Nefropatía endémica mesoamericana: Una enfermedad renal crónica de origen no tan desconocido. Nefrología 2021, 41, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabanino, R.G.; Aguilar, R.; Silva, C.R.; Mercado, M.O.; Merino, R.L. Nefropatía terminal en pacientes de un hospital de referencia en El Salvador. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2002, 12, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinder, C. Heat-induced kidney disease: Understanding the impact. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 297, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, V.S.; Garcia-Trabanino, R.; Rodriguez, G.; Madero, M. Mesoamerican nephropathy (MEN): What we know so far. Int. J. Nephrol. Renov. Dis. 2020, 13, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, A.; Murage, P.; Haque, F. Understanding the relationship between climate change-related meteorological factors and chronic kidney disease (CKD) and CKD of unknown origin (CKDu) in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Environ. Res. 2025, 286, 122928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, C.L.; Hess, H.W.; Lucas, R.A.I.; Glaser, J.; Saran, R.; Bragg-Gresham, J.; Wegman, D.H.; Hansson, E.; Minson, C.T.; Schlader, Z.J. Occupational heat exposure and the risk of chronic kidney disease of nontraditional origin in the United States. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2021, 321, R141–R151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlader, Z.J.; Hostler, D.; Parker, M.D.; Pryor, R.R.; Lohr, J.W.; Johnson, B.D.; Chapman, C.L. The potential for renal injury elicited by physical work in the heat. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, J.; Lemery, J.; Rajagopalan, B.; Diaz, H.F.; García-Trabanino, R.; Taduri, G.; Madero, M.; Amarasinghe, M.; Abraham, G.; Anutrakulchai, S.; et al. Climate Change and the Emergent Epidemic of CKD from Heat Stress in Rural Communities: The Case for Heat Stress Nephropathy. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 11, 1472–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, V.M.; Fadrowski, J.J.; Jaar, B.G. Global dimensions of chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu): A modern era environmental and/or occupational nephropathy? BMC Nephrol. 2015, 16, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijkström, J.; González-Quiroz, M.; Hernandez, M.; Trujillo, Z.; Hultenby, K.; Ring, A.; Söderberg, M.; Aragón, A.; Elinder, C.-G.; Wernerson, A. Renal morphology, clinical findings, and progression rate in mesoamerican nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 69, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, K.; Hwang, K.; Westcott, J.L.; Saleem, S.; Ali, S.A.; Jessani, S.; Patel, A.; Kavi, A.; Somannavar, M.S.; Goudar, S.S.; et al. Associations between ambient temperature and pregnancy outcomes from three south Asian sites of the Global Network Maternal Newborn Health Registry: A retrospective cohort study. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 130, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chersich, M.F.; Pham, M.D.; Areal, A.; Haghighi, M.M.; Manyuchi, A.; Swift, C.P.; Wernecke, B.; Robinson, M.; Hetem, R.; Boeckmann, M.; et al. Associations between high temperatures in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirths: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 371, m3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, B.M.; Garcia, D.L.; Anderson, S. Glomeruli and blood pressure: Less of one, more the other? Am. J. Hypertens. 1988, 1, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Elias, A.C.; Brenner, B.M.; Luyckx, V.A. Climate change and its influence in nephron mass. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2023, 33, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, M.; Murray, O.; O’Shea, P.M.; Mulkerrin, E.C. Increased rates of hypernatraemia during modest heatwaves in temperate climates. QJM 2019, 113, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nøhr, N.; Jepsen, R.; Jørsboe, H.; Lophaven, S.; Koch, S. Physiological responses to heat exposure in a general population cohort in Denmark: The Lolland–Falster Health Study. Eur. J. Public Health 2024, 34, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, E.; Grossmann, M.; Warren, A.M. Dysnatremia in a changing climate: A global systematic review of the association between serum sodium and ambient temperature. Clin. Endocrinol. 2024, 100, 527–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheimer, B.; Sterea-Grossu, A.; Falhammar, H.; Calissendorff, J.; Skov, J.; Lindh, J.D. Current and Future Burdens of Heat-Related Hyponatremia: A Nationwide Register–Based Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 107, e2388–e2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flahault, A.; Panico, A.; Fifre, G.; Massy, Z.A.; Frimat, L.; Bayer, F.; Metzger, M.; De Pinho, N.A.; Lequy, E. Heatwaves and plasma sodium disturbances in patients with chronic kidney disease. Environ. Int. 2025, 204, 109800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blauw, L.L.; Aziz, N.A.; Tannemaat, M.R.; Blauw, C.A.; De Craen, A.J.; Pijl, H.; Rensen, P.C.N. Diabetes incidence and glucose intolerance prevalence increase with higher outdoor temperature. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2017, 5, e000317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meo, S.A.; Shaikh, N.; Abukhalaf, F.A.; Meo, A.S.; Klonoff, D.C. Effect of climate change, extreme temperatures (heat and cold) on diabetes mellitus risk, hospitalization, and mortality: Global Evidenced Based Study. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1677522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, G.P.; Sigal, R.J.; McGinn, R. Body temperature regulation in diabetes. Temperature 2016, 3, 119–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Feng, X.; Sun, W.; Wang, F.; Lu, C. Independent and synergistic effects of extreme heat and NO2 pollution on diabetic nephropathy in a type II diabetes mouse model. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 375, 126321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-F.; Chou, C.-L.; Chung, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-K.; Chien, W.-C.; Feng, C.-H.; Chu, P. Risk of chronic kidney disease in patients with heat injury: A nationwide longitudinal cohort study in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romine, J.; Cullen, D.; Galperin, E.; Mattson, H.; Vassalotti, J.A.; Tang, K.; Gordon, A.S. High Heat Exposure and Medical Utilization among the CKD Population. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2025, 20, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerspink, H.J.L.; Stefánsson, B.V.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Chertow, G.M.; Greene, T.; Hou, F.-F.; Mann, J.F.E.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lindberg, M.; Rossing, P.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1436–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Heerspink, H.J.L.; Chertow, G.M.; Correa-Rotter, R.; Gasparrini, A.; Jongs, N.; Langkilde, A.M.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Mistry, M.N.; Rossing, P.; et al. Ambient heat exposure and kidney function in patients with chronic kidney disease: A post-hoc analysis of the DAPA-CKD trial. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e225–e233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remigio, R.V.; Jiang, C.; Raimann, J.; Kotanko, P.; Usvyat, L.; Maddux, F.W.; Kinney, P.; Sapkota, A. Association of Extreme Heat Events With Hospital Admission or Mortality Among Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e198904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Wettstein, Z.S.; Kshirsagar, A.V.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Hang, Y.; Rappold, A.G. Elevated Ambient Temperature Associated with Increased Cardiovascular Disease–RISK among patients on hemodialysis. Kidney Int. Rep. 2024, 9, 2946–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojuc-Konigsberg, G.; Raines, N.; Chopra, B.; Caplin, B. The Impact of Heat Exposure on Kidney Transplant. In Proceedings of the 2025 National Kidney Foundation Spring Clinical Meetings, Boston, MA, USA, 9–13 April 2025; National Kidney Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Abstract #6896. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valcheva, E.; Dimov, N. Rising Global Temperatures and Kidney Health: A Comprehensive Review of Current Evidence. Life 2025, 15, 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121897

Valcheva E, Dimov N. Rising Global Temperatures and Kidney Health: A Comprehensive Review of Current Evidence. Life. 2025; 15(12):1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121897

Chicago/Turabian StyleValcheva, Evelina, and Nikolay Dimov. 2025. "Rising Global Temperatures and Kidney Health: A Comprehensive Review of Current Evidence" Life 15, no. 12: 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121897

APA StyleValcheva, E., & Dimov, N. (2025). Rising Global Temperatures and Kidney Health: A Comprehensive Review of Current Evidence. Life, 15(12), 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121897