The Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Mechanism of Actions of GLP-1RAs

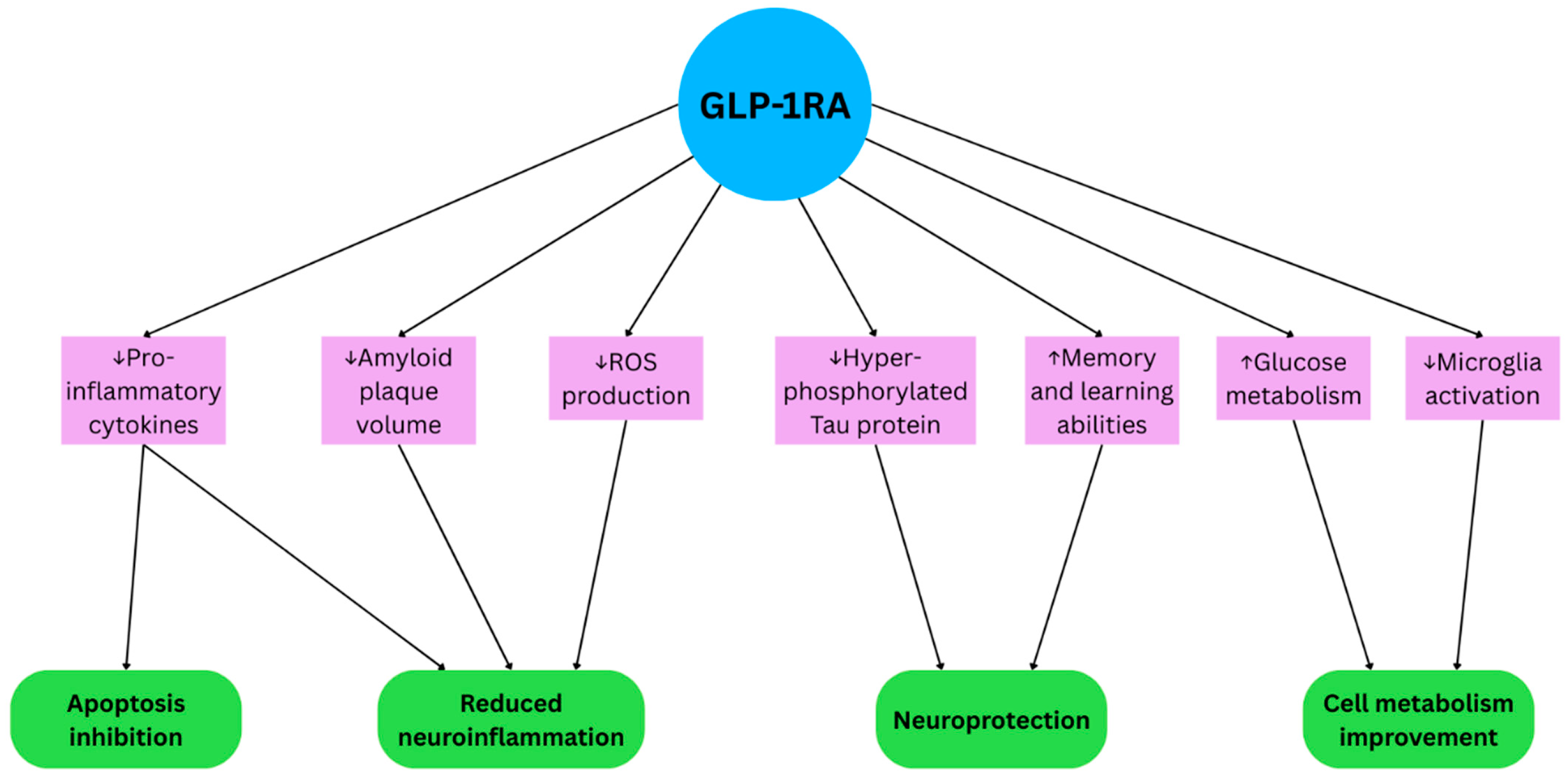

2.1. GLP-1RAs in Alzheimer’s Disease

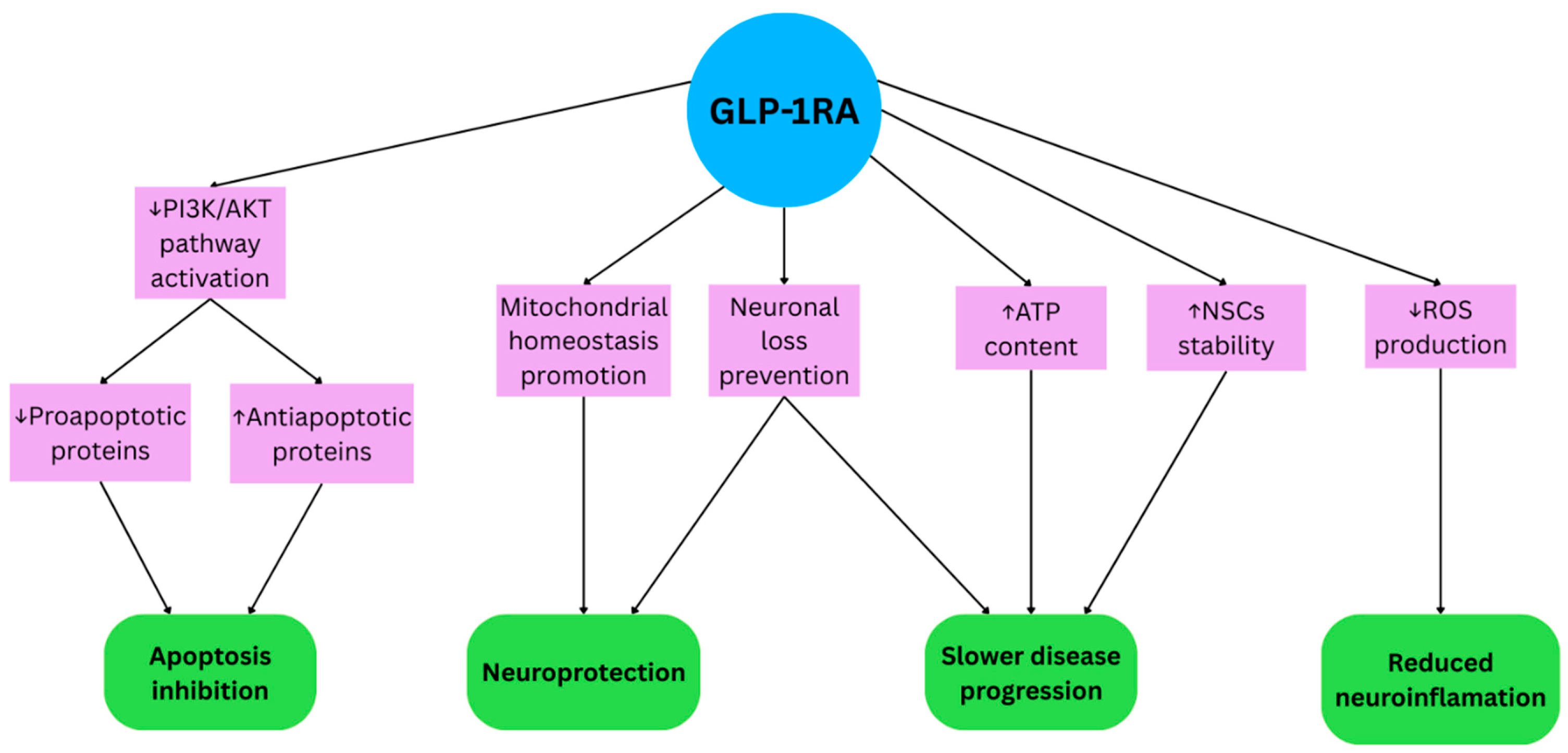

2.2. GLP-1RAs in Parkinson’s Disease

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Results of Clinical Trials with GLP-1RAs in AD

3.2. Results of Clinical Trials with GLP-1RAs in Parkinsonism

| Number | Citation | Study Group, (n) | Age, Years | Intervention (Drug and Dose) | Clinical Trial Duration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aviles-Olmos et al., 2013 [46] | Exenatide (n = 20) Conventional PD medication (n = 24) | Exenatide 51.6 (7.8) Conventional PD medication 48.4 (7.4) | Exenatide, 5 μg twice a day for 1 month and 10 μg twice a day for 11 months. Total duration of treatment: 12 months | 14 months | Improvement of the exenatide group compared to controls in MDS-UPDRS part 3 OFF state after 12 months and 14 months. Improvement of cognitive function in the Mattis dementia rating scale–2 at 14 months compared with deterioration in control patients. |

| 2 | Athauda et al., 2017 [24] | Exenatide (n = 31) Placebo (n = 29) | Exenatide 61.6 (8.2) Placebo 57.8 (8.0) | Exenatide 2 mg | 48 weeks | Improvement of the exenatide group compared to controls in MDS-UPDRS part 3 OFF state after 48 and 60 weeks. No cognitive improvement. |

| 3 | Athauda et al., 2019 [47] | Post hoc analysis of factors predicting response assessed that more disease severity and longer disease duration may benefit less from exenatide than patients with less severity and shorter duration. | ||||

| 4 | Athauda et al., 2018 [48] | Improvement in emotional dysfunction/depression across the NMSS, MDS-UPDRS Part 1 and MADRS assessment. Improvement in the “well-being” domain of PDQ-39. No statistical significance in cognitive functions and other non-motor symptoms. | ||||

| 5 | Athauda et al., 2019 [49] | Higher levels of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) phosphorylation at tyrosine sites and higher levels of phosphorylated mTOR and phosphoinositide-3-kinase/Akt (PI3K/AKT) expression in the intervention group compared to the controls. | ||||

| 6 | Meissner et al., 2024 [51] | Lixisenatide (n = 78) Placebo (n = 78) | Lixisenatide 59.5 ± 8.1 Placebo 59.9 ± 8.4 | Lixisenatide 20 μg | 48 weeks | Lixisenatide modestly reduced motor disability progression in patients with early PD as compared with a placebo but had gastrointestinal side effects. |

| 7 | McGarry et al., 2024 [50] | NLY01 2.5 mg (n = 85) NLY01 5 mg (n = 85) Placebo (n = 84) | NLY01 2.5 mg 62.1 ± 9.0 NLY01 5 mg 60.6 ± 10.0 Placebo 61.8 ± 8.1 | Exenatide and polyethylene glycol (NLY01) (2.5 mg/5 mg/placebo) | 36 weeks | NLY01 did not differ between the active group compared with placebo. |

| Number | Condition | Title | ClinicalTrials.gov ID | Phase | Status | Intervention (Drug and Dose) | Clinical Trial Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parkinson’s disease | Effects of Exenatide on Motor Function and the Brain | NCT03456687 | Phase 1 | Completed | Exenatide 2 mg once a week | 12 months |

| 2 | Parkinson’s disease | Exenatide Treatment in Parkinson’s Disease | NCT04305002 | Phase 2 | Unknown status | Exenatide 2 mg once a week | 18 months |

| 3 | Parkinson’s disease | GLP1R in Parkinson’s Disease | NCT03659682 | Phase 2 | Not yet recruiting | Semaglutide 1 mg once a week | 48 months |

| 4 | Parkinson’s disease | Exenatide Once Weekly Over 2 Years as a Potential Disease Modifying Treatment for Parkinson’s Disease | NCT04232969 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Exenatide extended release 2 mg once a week | 96 weeks |

| 5 | Parkinson’s disease | GLP1R in Parkinson’s Disease | NCT03659682 | Phase 2 | Not yet recruiting | Semaglutide 1 mg once a week | 48 months |

| 6 | Early Parkinson’s disease | SR-Exenatide (PT320) to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety in Patients With Early Parkinson’s Disease | NCT04269642 | Phase 2 | Unknown status | SR-exenatide (PT320) 2 mg once a week PT320 2.5 mg every 2 weeks | 48 weeks |

| 7 | Multiple system atrophy | Exenatide Once-weekly as a Treatment for Multiple System Atrophy | NCT04431713 | Phase 2 | Unknown status | Exenatide | 12 months |

4. Clinical Implications of the Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holst, J.J. The physiology of glucagon-like peptide 1. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 1409–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.; Lund, A.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsbøll, T. Glucagon-like peptide 1 in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 390–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.; Bain, S.; Kanamarlapudi, V. Recent advances in understanding the role of glucagon-like peptide 1. F1000Research 2020, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, P.; Chepurny, O.G.; Holz, G.G. Regulation of glucose homeostasis by GLP-1. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2014, 121, 23–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darsalia, V.; Larsson, M.; Nathanson, D.; Klein, T.; Nyström, T.; Patrone, C. Glucagon-like receptor 1 agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors: Potential therapies for the treatment of stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2015, 35, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.P. DPP-4 inhibition and neuroprotection: Do mechanisms matter? Diabetes 2013, 62, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayoub, B.M.; Mowaka, S.; Safar, M.M.; Ashoush, N.; Arafa, M.G.; Michel, H.E.; Tadros, M.M.; Elmazar, M.M.; Mousa, S.A. Repositioning of Omarigliptin as a once-weekly intranasal Anti-parkinsonian Agent. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, D.; Mietlicki-Baase, E.G. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 in the Brain: Where Is It Coming From, Where Is It Going? Diabetes 2019, 68, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.E.; Drucker, D.J. Pharmacology, physiology, and mechanisms of incretin hormone action. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 819–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, T.; Kaur, M.; Shekhawat, D.; Aggarwal, R.; Nanda, N.; Sahni, D. Investigating the Glucagon-like Peptide-1 and Its Receptor in Human Brain: Distribution of Expression, Functional Implications, Age-related Changes and Species Specific Characteristics. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, H.H.; Fabricius, K.; Barkholt, P.; Niehoff, M.L.; Morley, J.E.; Jelsing, J.; Pyke, C.; Knudsen, L.B.; Farr, S.A.; Vrang, N. The GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Liraglutide Improves Memory Function and Increases Hippocampal CA1 Neuronal Numbers in a Senescence-Accelerated Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2015, 46, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Duffy, K.B.; Ottinger, M.A.; Ray, B.; Bailey, J.A.; Holloway, H.W.; Tweedie, D.; Perry, T.; Mattson, M.P.; Kapogiannis, D.; et al. GLP-1 receptor stimulation reduces amyloid-beta peptide accumulation and cytotoxicity in cellular and animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2010, 19, 1205–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Perry, T.; Kindy, M.S.; Harvey, B.K.; Tweedie, D.; Holloway, H.W.; Powers, K.; Shen, H.; Egan, J.M.; Sambamurti, K.; et al. GLP-1 receptor stimulation preserves primary cortical and dopaminergic neurons in cellular and rodent models of stroke and Parkinsonism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopade, P.; Chopade, N.; Zhao, Z.; Mitragotri, S.; Liao, R.; Chandran Suja, V. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease therapies in the clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2022, 8, e10367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Barve, K.H.; Kumar, M.S. Recent Advancements in Pathogenesis, Diagnostics and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 1106–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkiewicz, J.J.; Siuda, J. Comparison of autonomic dysfunction in patients with Parkinson’s Disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and multiple system atrophy. Neurol. I Neurochir. Pol. 2024, 58, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrino, R.; Schapira, A.H.V. Parkinson disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, P.W.; de Pablo Fernandez, E.; König, A.; Outeiro, T.F.; Jaunmuktane, Z.; Warner, T.T. Type 2 Diabetes and Parkinson’s Disease: A Focused Review of Current Concepts. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2023, 38, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J.L.Y.; de Pablo-Fernandez, E.; Foltynie, T.; Noyce, A.J. The Association Between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2020, 10, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiela, T.; Jarosz-Chobot, P.; Gorzkowska, A. Glucose Metabolism Disorders and Parkinson’s Disease: Coincidence or Indicator of Dysautonomia? Healthcare 2024, 12, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiela, T.; Węgrzynek, J.; Kasprzyk, A.; Waksmundzki, D.; Wilczek, D.; Gorzkowska, A. If Not Insulin Resistance so What?—Comparison of Fasting Glycemia in Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease and Atypical Parkinsonism. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2022, 15, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Dutheil, F.; Durand, E.; Rieu, I.; Mulliez, A.; Fantini, M.L.; Boirie, Y.; Durif, F. Glucose dysregulation in Parkinson’s disease: Too much glucose or not enough insulin? Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 55, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athauda, D.; Foltynie, T. The glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP) receptor as a therapeutic target in Parkinson’s disease: Mechanisms of action. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 802–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athauda, D.; Maclagan, K.; Skene, S.S.; Bajwa-Joseph, M.; Letchford, D.; Chowdhury, K.; Hibbert, S.; Budnik, N.; Zampedri, L.; Dickson, J.; et al. Exenatide once weekly versus placebo in Parkinson’s disease: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza-Naval, M.J.; Del Marco, A.; Hierro-Bujalance, C.; Alves-Martinez, P.; Infante-Garcia, C.; Vargas-Soria, M.; Herrera, M.; Barba-Cordoba, B.; Atienza-Navarro, I.; Lubian-Lopez, S.; et al. Liraglutide Reduces Vascular Damage, Neuronal Loss, and Cognitive Impairment in a Mixed Murine Model of Alzheimer’s Disease and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 741923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, M.; Liu, L.; Chen, Z. GLP-1 improves the neuronal supportive ability of astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease by regulating mitochondrial dysfunction via the cAMP/PKA pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 188, 114578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gejl, M.; Gjedde, A.; Egefjord, L.; Møller, A.; Hansen, S.B.; Vang, K.; Rodell, A.; Brændgaard, H.; Gottrup, H.; Schacht, A.; et al. In Alzheimer’s Disease, 6-Month Treatment with GLP-1 Analog Prevents Decline of Brain Glucose Metabolism: Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, C.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, B.; Tong, A.; Zhong, Q.; Zhong, Z. Semaglutide ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease and restores oxytocin in APP/PS1 mice and human brain organoid models. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 180, 117540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Hong, F.; Yang, S. Amyloidosis in Alzheimer’s Disease: Pathogeny, Etiology, and Related Therapeutic Directions. Molecules 2022, 27, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, G.; Kim, Y.K.; Song, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 suppresses neuroinflammation and improves neural structure. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 152, 104615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Q.; Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Yu, P. Tirzepatide shows neuroprotective effects via regulating brain glucose metabolism in APP/PS1 mice. Peptides 2024, 179, 171271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, D.; Solmaz, V.; Çavuşoğlu, T.; Meral, A.; Ateş, U.; Erbaş, O. Neuroprotective Effects of Exenatide in a Rotenone-Induced Rat Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 354, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, L.L.; Liu, Y.Q.; Shen, Y.; Fan, Y.; Yu, W.B.; Jiang, D.L.; Tang, Y.L.; Yang, Y.J.; Wu, P.; Zuo, C.T.; et al. Neuroprotection of Exendin-4 by Enhanced Autophagy in a Parkinsonian Rat Model of α-Synucleinopathy. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 962–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Z.; Lu, D.; Li, T.; Ding, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Xu, A. The Neuroprotection of Liraglutide Against Ischaemia-induced Apoptosis through the Activation of the PI3K/AKT and MAPK Pathways. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briyal, S.; Shah, S.; Gulati, A. Neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic effects of liraglutide in the rat brain following focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience 2014, 281, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, V.; Tseng, K.Y.; Kuo, T.T.; Huang, E.Y.; Lan, K.L.; Chen, Z.R.; Ma, K.H.; Greig, N.H.; Jung, J.; Choi, H.I.; et al. Attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction and morphological disruption with PT320 delays dopamine degeneration in MitoPark mice. J. Biomed. Sci. 2024, 31, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, R.; Liu, K.; Lai, H.; Liao, C.; Li, J.; Tu, H. GLP-1/GIP dual agonist tirzepatide alleviates mice model of Parkinson’s disease by promoting mitochondrial homeostasis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 165, 115443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Zou, X.; Ma, D.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, T.; Shen, B.; Cheng, O. The GLP1R Agonist Semaglutide Inhibits Reactive Astrocytes and Enhances the Efficacy of Neural Stem Cell Transplantation Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease Mice. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e17664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.Y.; Hölscher, C.; Yue, X.H.; Zhang, S.X.; Wang, X.H.; Qiao, F.; Yang, W.; Qi, J.S. Lixisenatide rescues spatial memory and synaptic plasticity from amyloid β protein-induced impairments in rats. Neuroscience 2014, 277, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, P.L.; Hölscher, C. Liraglutide can reverse memory impairment, synaptic loss and reduce plaque load in aged APP/PS1 mice, a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 2014, 76 Pt A, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gejl, M.; Brock, B.; Egefjord, L.; Vang, K.; Rungby, J.; Gjedde, A. Blood-Brain Glucose Transfer in Alzheimer’s disease: Effect of GLP-1 Analog Treatment. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.T.; Wroolie, T.E.; Tong, G.; Foland-Ross, L.C.; Frangou, S.; Singh, M.; McIntyre, R.S.; Roat-Shumway, S.; Myoraku, A.; Reiss, A.L.; et al. Neural correlates of liraglutide effects in persons at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 356, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins, R.J.; Mustapic, M.; Chia, C.W.; Carlson, O.; Gulyani, S.; Tran, J.; Li, Y.; Mattson, M.P.; Resnick, S.; Egan, J.M.; et al. A Pilot Study of Exenatide Actions in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2019, 16, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dei Cas, A.; Micheli, M.M.; Aldigeri, R.; Gardini, S.; Ferrari-Pellegrini, F.; Perini, M.; Messa, G.; Antonini, M.; Spigoni, V.; Cinquegrani, G.; et al. Long-acting exenatide does not prevent cognitive decline in mild cognitive impairment: A proof-of-concept clinical trial. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2024, 47, 2339–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weihe, E.; Depboylu, C.; Schütz, B.; Schäfer, M.K.; Eiden, L.E. Three types of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive CNS neurons distinguished by dopa decarboxylase and VMAT2 co-expression. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2006, 26, 659–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviles-Olmos, I.; Dickson, J.; Kefalopoulou, Z.; Djamshidian, A.; Ell, P.; Soderlund, T.; Whitton, P.; Wyse, R.; Isaacs, T.; Lees, A.; et al. Exenatide and the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2730–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athauda, D.; Maclagan, K.; Budnik, N.; Zampedri, L.; Hibbert, S.; Aviles-Olmos, I.; Chowdhury, K.; Skene, S.S.; Limousin, P.; Foltynie, T. Post hoc analysis of the Exenatide-PD trial-Factors that predict response. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019, 49, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athauda, D.; Maclagan, K.; Budnik, N.; Zampedri, L.; Hibbert, S.; Skene, S.S.; Chowdhury, K.; Aviles-Olmos, I.; Limousin, P.; Foltynie, T. What Effects Might Exenatide have on Non-Motor Symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease: A Post Hoc Analysis. J. Park. Dis. 2018, 8, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athauda, D.; Gulyani, S.; Karnati, H.K.; Li, Y.; Tweedie, D.; Mustapic, M.; Chawla, S.; Chowdhury, K.; Skene, S.S.; Greig, N.H.; et al. Utility of Neuronal-Derived Exosomes to Examine Molecular Mechanisms That Affect Motor Function in Patients with Parkinson Disease: A Secondary Analysis of the Exenatide-PD Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, A.; Rosanbalm, S.; Leinonen, M.; Olanow, C.W.; To, D.; Bell, A.; Lee, D.; Chang, J.; Dubow, J.; Dhall, R.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of NLY01 in early untreated Parkinson’s disease: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, W.G.; Remy, P.; Giordana, C.; Maltête, D.; Derkinderen, P.; Houéto, J.L.; Anheim, M.; Benatru, I.; Boraud, T.; Brefel-Courbon, C.; et al. LIXIPARK Study Group Trial of Lixisenatide in Early Parkinson’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, R.Y. Epidemiology of atypical parkinsonian syndromes. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2021, 34, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Z.; Shang, H. Multiple system atrophy: An update and emerging directions of biomarkers and clinical trials. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 2324–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koekkoek, P.S.; Kappelle, L.J.; van den Berg, E.; Rutten, G.E.; Biessels, G.J. Cognitive function in patients with diabetes mellitus: Guidance for daily care. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Q.; Qi, X.; Gurney, M.; Perry, G.; Volkow, N.D.; Davis, P.B.; Kaelber, D.C.; Xu, R. Associations of semaglutide with first-time diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: Target trial emulation using nationwide real-world data in the US. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2024, 20, 8661–8672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Luo, Z.; Li, C.; Huang, X.; Shiroma, E.J.; Simonsick, E.M.; Chen, H. Changes in Body Composition Before and After Parkinson’s Disease Diagnosis. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2021, 36, 1617–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, M.; Greenland, J.C.; Williams-Gray, C.H. The Gastrointestinal Dysfunction Scale for Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2021, 36, 2358–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węgrzynek-Gallina, J.; Chmiela, T.; Kasprzyk, A.; Borończyk, M.; Siuda, J. Metabolic effects of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol. I Neurochir. Pol. 2025, 59, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, J.; Wu, B.; Ling, Y.; Guo, Q.; Wang, S.; Liu, L.; Jiang, N.; Chen, L.; Liu, J. Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation Treats Parkinson’s Disease Patients with Cardiovascular Disease Comorbidity: A Retrospective Study of a Single Center Experience. Brain Sci. 2022, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Articles in English language. | Research types of case studies, case series, reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, books, opinion articles, etc. |

| The research type of clinical trial is a randomized controlled trial. | Duplicate items. |

| Studies describing the use of GLP-1RA in the treatment of patients with neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease, atypical Parkinsonisms, including Multiple System Atrophy, Dementia with Lewy Bodies, Corticobasal Dementia, Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, Alzheimer’s disease, and Frontotemporal Dementia. | Studies describing the use of GLP-1RA in animals or cell experiments. |

| Number | Citation | Study Group, (n) | Age, Years | Intervention (Drug and Dose) | Clinical Trial Duration | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gejl et al., 2016 [27] | Liraglutide (n = 18) Placebo (n = 20) | Placebo 66.6 ± 1.8 Liraglutide 63.1 ± 1.3 | 0.6 mg (1 week) ⟶ 1.2 mg (1 week) ⟶ 1.8 mg (thereafter) s.c. liraglutide | 26 weeks | Liraglutide prevented the decline in CMRglc seen with placebo (significant decreases in precuneus, parietal, temporal, occipital, and cerebellum). In the liraglutide group, CMRglc rose slightly but not significantly. No group differences in amyloid deposition or cognition. |

| 2 | Gejl et al., 2017 [41] | Liraglutide (n = 18) Placebo (n = 20) | Placebo 66.6 ± 1.8 Liraglutide 63.1 ± 1.3 | 0.6 mg (1 week) ⟶ 1.2 mg (1 week) ⟶ 1.8 mg (thereafter) s.c. liraglutide | 26 weeks | At baseline, CMRglc correlated positively with cognition and inversely with AD duration. Liraglutide increased Tmax from 0.72 to 1.1 μmol/g/min, reaching healthy control levels (p < 0.0001). No change in placebo (p = 0.24). |

| 3 | Watson et al., 2019 [42] | Liraglutide (n = 22) Placebo (n = 21) | Placebo 60.3 ± 5.4, 14 females Liraglutide 61.4 ± 6.1, 14 females | 0.6 mg (1 week) ⟶ 1.2 mg (1 week) ⟶ 1.8 mg (thereafter) s.c. liraglutide | 12 weeks | Higher fasting plasma glucose was linked to reduced hippocampal–frontal connectivity. After 6 months, the active group showed improved default mode network connectivity vs. placebo, with no cognitive differences. Glucose tolerance declined slightly more with liraglutide (p = 0.06). |

| 4 | Mullins et al., 2019 [43] | Exenatide (n = 14) Placebo (n = 13) | Placebo 74.0 ± 6.4 Exenatide 71.7 ± 6.9 | Participants received s.c. exenatide 5 mcg twice daily (or placebo) for 1 week, then 10 mcg twice daily for 78 weeks. | 18 months | Exenatide was safe and well-tolerated in MCI/early AD. Neuropsychological outcomes were largely similar, except for improved digit-span forward at 6 months. After 18 months, no group differences in GM atrophy or fluid biomarkers, except for a decrease in EV Aβ42 with exenatide (p = 0.045). |

| 5 | Dei Cas et al., 2024 [44] | Exenatide (n = 17) Placebo (n = 15) | Placebo 72 ± 6 Exenatide 74 ± 4 | Long-acting exenatide 2 mg SC once a week. | 32 weeks | No significant effect of exenatide on ADAS-Cog11 (p = 0.17). A gender interaction was observed (p = 0.04): women on exenatide showed cognitive decline (p = 0.018). Exenatide reduced fasting glucose (p = 0.02) and body weight (p = 0.03). |

| Number | Condition | Title | ClinicalTrials.gov ID | Phase | Status | Intervention (Drug and Dose) | Clinical Trial Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Early Alzheimer’s disease | A Research Study Investigating Semaglutide in People With Early Alzheimer’s Disease (EVOKE) | NCT04777396 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Semaglutide PO once a day, dose gradually increased to 14 mg. | 173 weeks |

| 2 | Early Alzheimer’s disease | A Research Study Investigating Semaglutide in People With Early Alzheimer’s Disease (EVOKE Plus) | CT04777409 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Semaglutide PO once a day, dose gradually increased to 14 mg. | 173 weeks |

| 4 | Alzheimer’s disease | A Research Study Looking at the Effect of Semaglutide on the Immune System and Other Biological Processes in People With Alzheimer’s Disease | NCT05891496 | Phase 3 | Active, not recruiting | Semagllutide SC 0.25 mg–1 mg once a week. | 12 weeks |

| 5 | Alzheimer’s disease | Evaluating Liraglutide in Alzheimer’s Disease | NCT01843075 | Phase 2 | Unknown status | Liraglutide 1.8 mg once a day. | 12 months |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pilśniak, J.; Węgrzynek-Gallina, J.; Bednarczyk, B.; Buczek, A.; Pilśniak, A.; Chmiela, T.; Jarosińska, A.; Siuda, J.; Holecki, M. The Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials. Life 2025, 15, 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121893

Pilśniak J, Węgrzynek-Gallina J, Bednarczyk B, Buczek A, Pilśniak A, Chmiela T, Jarosińska A, Siuda J, Holecki M. The Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials. Life. 2025; 15(12):1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121893

Chicago/Turabian StylePilśniak, Joanna, Julia Węgrzynek-Gallina, Błażej Bednarczyk, Aleksandra Buczek, Aleksandra Pilśniak, Tomasz Chmiela, Agnieszka Jarosińska, Joanna Siuda, and Michał Holecki. 2025. "The Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials" Life 15, no. 12: 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121893

APA StylePilśniak, J., Węgrzynek-Gallina, J., Bednarczyk, B., Buczek, A., Pilśniak, A., Chmiela, T., Jarosińska, A., Siuda, J., & Holecki, M. (2025). The Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease: A Literature Review of Clinical Trials. Life, 15(12), 1893. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15121893