The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitors on Atherogenesis: A Systematic Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

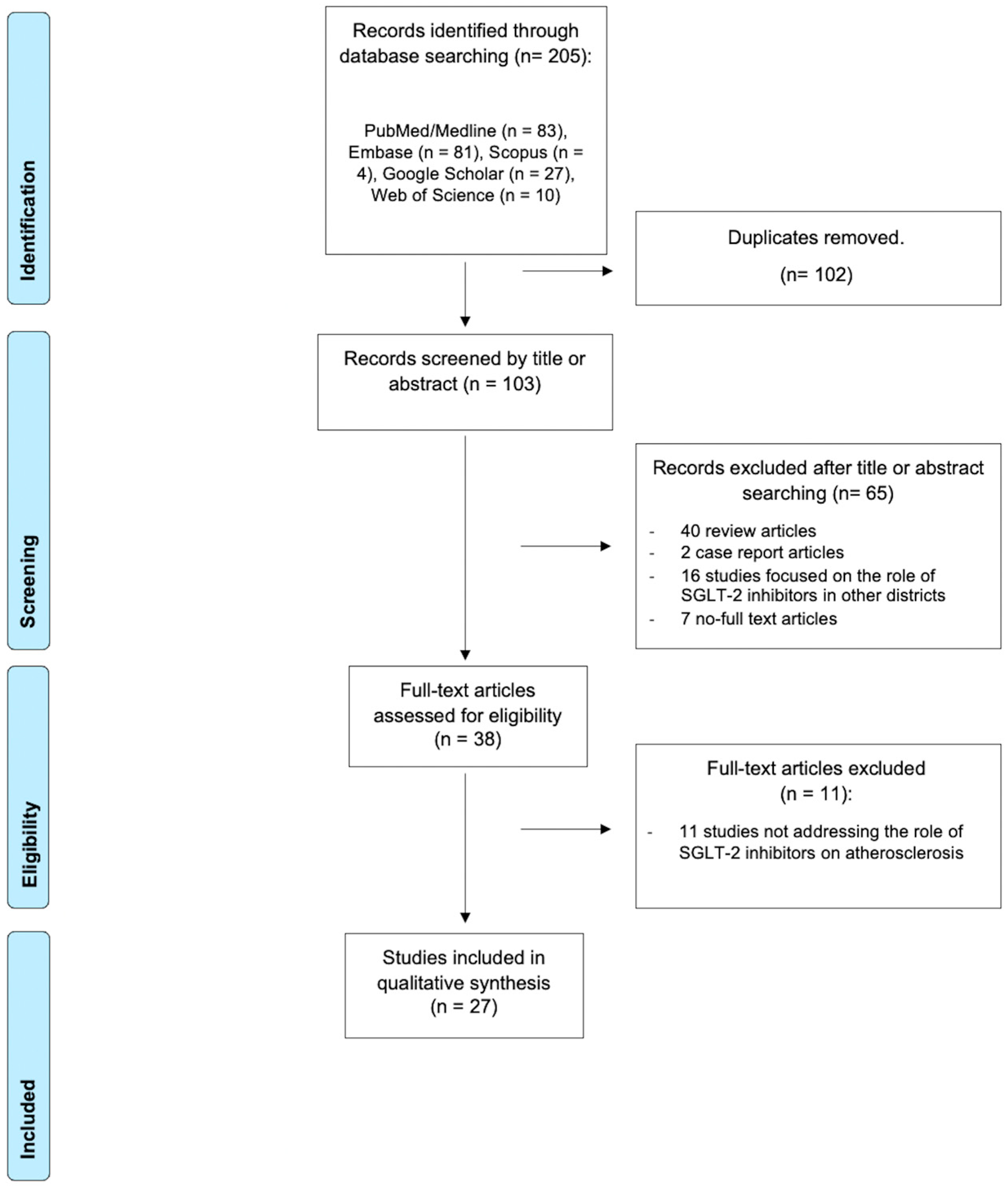

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.4. Summary Measures and Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Preclinical Evidence

3.1.1. SGLT2i and Endothelial Cells

3.1.2. SGLT2is and Monocytes/Macrophages Pathways

3.1.3. SGLT2i and Inflammatory Pathways

3.1.4. SGLT2i and Thrombosis

3.1.5. SGLT2 and Vascular Calcifications

3.2. Clinical Evidence

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | Acute coronary syndrome |

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| EC | Endothelial cell |

| FC | Fibrous cap |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MACE | Major adverse cardiovascular events |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 |

| NHE1 | Sodium-hydrogen exchanger |

| NLRP3 | Nucleotide-binding Oligomerization Domain-Like Receptor Protein 3 |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| OCT | Optical coherence tomography |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SGLT2i | Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| VSMCs | Vascular smooth muscle cells |

References

- Lu, X.; Xie, Q.; Pan, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Peng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Tong, N. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: Pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montone, R.A.; Pitocco, D.; Gurgoglione, F.L.; Rinaldi, R.; Del Buono, M.G.; Camilli, M.; Rizzi, A.; Tartaglione, L.; Rizzo, G.E.; Di Leo, M.; et al. Microvascular complications identify a specific coronary atherosclerotic phenotype in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, T.K.; Gislason, G.H.; Køber, L.; Rasmussen, S.; Rasmussen, J.N.; Abildstrøm, S.Z.; Hansen, M.L.; Folke, F.; Buch, P.; Madsen, M.; et al. Diabetes patients requiring glucose-lowering therapy and nondiabetics with a prior myocardial infarction carry the same cardiovascular risk: A population study of 3.3 million people. Circulation 2008, 117, 1945–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopaschuk, G.D.; Verma, S. Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Benefits of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors: A State-of-the-Art Review. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2020, 5, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurgoglione, F.L.; Crea, F.; Niccoli, G.; Galli, M. Can sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors stabilize coronary atherosclerotic plaques? Evidence from imaging studies. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2025, 11, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Bělohlávek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.-P.; Choi, D.-J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in Heart Failure with a Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Claggett, B.; de Boer, R.A.; DeMets, D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.P.; Martinez, F.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, B.; Perkovic, V.; Mahaffey, K.W.; de Zeeuw, D.; Fulcher, G.; Erondu, N.; Shaw, W.; Law, G.; Desai, M.; Matthews, D.R.; et al. Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Raz, I.; Bonaca, M.P.; Mosenzon, O.; Kato, E.T.; Cahn, A.; Silverman, M.G.; Zelniker, T.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, C.P.; Pratley, R.; Dagogo-Jack, S.; Mancuso, J.; Huyck, S.; Masiukiewicz, U.; Charbonnel, B.; Frederich, R.; Gallo, S.; Cosentino, F.; et al. Cardiovascular Outcomes with Ertugliflozin in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1425–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. The changing landscape of atherosclerosis. Nature 2021, 592, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.W.; Maehara, A.; Lansky, A.J.; de Bruyne, B.; Cristea, E.; Mintz, G.S.; Mehran, R.; McPherson, J.; Farhat, N.; Marso, S.P.; et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 226–235, Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, F.; Romagnoli, E.; Gatto, L.; La Manna, A.; Burzotta, F.; Ozaki, Y.; Marco, V.; Boi, A.; Fineschi, M.; Fabbiocchi, F.; et al. Relationship between coronary plaque morphology of the left anterior descending artery and 12 months clinical outcome: The CLIMA study. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlinge, D.; Maehara, A.; Ben-Yehuda, O.; Bøtker, H.E.; Maeng, M.; Kjøller-Hansen, L.; Engstrøm, T.; Matsumura, M.; Crowley, A.; Dressler, O.; et al. Identification of vulnerable plaques and patients by intracoronary near-infrared spectroscopy and ultrasound (PROSPECT II): A prospective natural history study. Lancet 2021, 397, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covani, M.; Niccoli, G.; Fujimoto, D.; Scalamera, R.; Vergallo, R.; Porto, I.; McNulty, I.; Lee, H.; Kakuta, T.; Jang, I.-K. Plaque Vulnerability and Cardiovascular Risk Factor Burden in Acute Coronary Syndrome: An Optical Coherence Tomography Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semo, D.; Obergassel, J.; Dorenkamp, M.; Hemling, P.; Strutz, J.; Hiden, U.; Müller, N.; Müller, U.A.; Zulfikar, S.A.; Godfrey, R.; et al. The Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitor Empagliflozin Reverses Hyperglycemia-Induced Monocyte and Endothelial Dysfunction Primarily through Glucose Transport-Independent but Redox-Dependent Mechanisms. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Römer, G.; Kerindongo, R.P.; Hermanides, J.; Albrecht, M.; Hollmann, M.W.; Zuurbier, C.J.; Preckel, B.; Weber, N.C. Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitors Ameliorate Endothelium Barrier Dysfunction Induced by Cyclic Stretch through Inhibition of Reactive Oxygen Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlos, A.; Broncel, M.; Woźniak, E.; Markiewicz, Ł.; Piastowska-Ciesielska, A.; Gorzelak-Pabiś, P. SGLT2 Inhibitors May Restore Endothelial Barrier Interrupted by 25-Hydroxycholesterol. Molecules 2023, 28, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yu, X.; Liu, Y.; Paik, D.T.; Justesen, J.M.; Chandy, M.; Jahng, J.W.S.; Zhang, T.; Wu, W.; Rwere, F.; et al. SGLT2 inhibitor ameliorates endothelial dysfunction associated with the common ALDH2 alcohol flushing variant. Sci. Transl. Med. 2023, 15, eabp9952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhong, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, J.; Deng, S.; Jiang, T.; Jiang, A.; Huang, Z.; Wang, J. Dapagliflozin improves the dysfunction of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) by downregulating high glucose/high fat-induced autophagy through inhibiting SGLT-2. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2025, 39, 108907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganbaatar, B.; Fukuda, D.; Shinohara, M.; Yagi, S.; Kusunose, K.; Yamada, H.; Soeki, T.; Hirata, K.; Sata, M. Empagliflozin ameliorates endothelial dysfunction and suppresses atherogenesis in diabetic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 875, 173040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, M.; Hiromura, M.; Mori, Y.; Kohashi, K.; Nagashima, M.; Kushima, H.; Watanabe, T.; Hirano, T. Amelioration of Hyperglycemia with a Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor Prevents Macrophage-Driven Atherosclerosis through Macrophage Foam Cell Formation Suppression in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetic Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, M.; Hiromura, M.; Mori, Y.; Kohashi, K.; Kushima, H.; Ohara, M.; Watanabe, T.; Andersson, O.; Hirano, T. Combination Therapy with a Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitor and a Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor Additively Suppresses Macrophage Foam Cell Formation and Atherosclerosis in Diabetic Mice. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 2017, 1365209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennig, J.; Scherrer, P.; Gissler, M.C.; Anto-Michel, N.; Hoppe, N.; Füner, L.; Härdtner, C.; Stachon, P.; Wolf, D.; Hilgendorf, I.; et al. Glucose lowering by SGLT2-inhibitor empagliflozin accelerates atherosclerosis regression in hyperglycemic STZ-diabetic mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Teng, D.; Xu, B.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Jia, W.; Gong, L.; Dong, H.; Zhong, L.; Yang, J. The SGLT2 Inhibitor Canagliflozin Reduces Atherosclerosis by Enhancing Macrophage Autophagy. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2023, 16, 999–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Peter, K. Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitor Dapagliflozin Stabilizes Diabetes--Induced Atherosclerotic Plaque Instability. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e022761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, W.; Ouyang, X.; Lei, X.; Wu, M.; Chen, L.; Wu, Q.; Deng, W.; Liang, Z. The SGLT-2 Inhibitor Dapagliflozin Has a Therapeutic Effect on Atherosclerosis in Diabetic ApoE−/− Mice. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 6305735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsu, Y.; Kokubo, H.; Bumdelger, B.; Yoshizumi, M.; Yamamotoya, T.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ueda, K.; Inoue, Y.; Inoue, M.-K.; Fujishiro, M.; et al. The SGLT2 Inhibitor Luseogliflozin Rapidly Normalizes Aortic mRNA Levels of Inflammation-Related but Not Lipid-Metabolism-Related Genes and Suppresses Atherosclerosis in Diabetic ApoE KO Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.H.; Oh, T.J.; Lee, G.; Maeng, H.J.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, K.M.; Choi, S.H.; Jang, H.C.; Lee, H.S.; Park, K.S.; et al. The beneficial effects of empagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, on atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice fed a western diet. Diabetologia 2017, 60, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-G.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, J.-J.; Kim, J.-S.; Lee, O.-H.; Kim, C.-K.; Kim, D.; Lee, Y.-H.; Oh, J.; Park, S.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Effect for Atherosclerosis Progression by Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitor in a Normoglycemic Rabbit Model. Korean Circ. J. 2020, 50, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, M.; Kubota, T.; Sakurai, Y.; Wada, N.; Shioda, S.; Yamauchi, T.; Kadowaki, T.; Kubota, N. The sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor tofogliflozin suppresses atherosclerosis through glucose lowering in ApoE-deficient mice with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2022, 10, e00971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Fu, J.; Tu, Q.; Shuai, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wu, F.; Cao, Z. The SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin attenuates atherosclerosis progression by inducing autophagy. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 80, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Koibuchi, N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Sueta, D.; Toyama, K.; Uekawa, K.; Ma, M.; Nakagawa, T.; Kusaka, H.; Kim-Mitsuyama, S. Glycemic control with empagliflozin, a novel selective SGLT2 inhibitor, ameliorates cardiovascular injury and cognitive dysfunction in obese and type 2 diabetic mice. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigoni, V.; Fantuzzi, F.; Carubbi, C.; Pozzi, G.; Masselli, E.; Gobbi, G.; Solini, A.; Bonadonna, R.C.; Dei Cas, A. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors antagonize lipotoxicity in human myeloid angiogenic cells and ADP-dependent activation in human platelets: Potential relevance to prevention of cardiovascular events. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seecheran, N.; Ramdeen, A.; Debideen, N.; Ali, K.; Grimaldos, K.; Grimaldos, G.; Karan, A.; Seecheran, R.; Seecheran, V.; Persad, S.; et al. The Effect of Empagliflozin on Platelet Function Profiles in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease in Trinidad: The EFFECT Pilot Study. Cardiol. Ther. 2021, 10, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberale, L.; Kraler, S.; Puspitasari, Y.M.; Bonetti, N.R.; Akhmedov, A.; Ministrini, S.; Montecucco, F.; Marx, N.; Lehrke, M.; Hartmann, N.-U.K.; et al. SGLT-2 inhibition by empagliflozin has no effect on experimental arterial thrombosis in a murine model of low-grade inflammation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Lan, Z.; Li, L.; Xie, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Liang, Q.; Dong, Q.; Feng, L.; et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor canagliflozin alleviates vascular calcification through suppression of nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, pyrin domain-containing-3 inflammasome. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2368–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Luo, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Sun, N.; Zhao, J.; Luo, W.; Zhang, J.; Tong, X.; et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors attenuate vascular calcification by suppressing endoplasmic reticulum protein thioredoxin domain containing 5 dependent osteogenic reprogramming. Redox Biol. 2024, 73, 103183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, H.; Chai, Q.; Wei, J.; Qin, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Qi, J.; Guo, C.; Lu, Z. Dapagliflozin targets SGLT2/SIRT1 signaling to attenuate the osteogenic transdifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardu, C.; Trotta, M.C.; Sasso, F.C.; Sacra, C.; Carpinella, G.; Mauro, C.; Minicucci, F.; Calabrò, P.; D’Amico, M.; D’Ascenzo, F.; et al. SGLT2-inhibitors effects on the coronary fibrous cap thickness and MACEs in diabetic patients with inducible myocardial ischemia and multi vessels non-obstructive coronary artery stenosis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurozumi, A.; Shishido, K.; Yamashita, T.; Sato, D.; Uchida, S.; Koyama, E.; Tamaki, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Miyashita, H.; Yokoyama, H.; et al. Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors Stabilize Coronary Plaques in Acute Coronary Syndrome with Diabetes Mellitus. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 214, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Gao, X.; Chen, T.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Xin, Y.; Shi, D.; Du, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhou, Y. Longitudinal assessment of coronary plaque regression related to sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor using coronary computed tomography angiography. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Leyte, D.J.; Zepeda-García, O.; Domínguez-Pérez, M.; González-Garrido, A.; Villarreal-Molina, T.; Jacobo-Albavera, L. Endothelial Dysfunction, Inflammation and Coronary Artery Disease: Potential Biomarkers and Promising Therapeutical Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Lim, S.; Lim, J.Y.; Kim, K.W.; Park, K.S.; Jang, H.C. Monocyte count as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in older Korean people. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dregoesc, M.I.; Țigu, A.B.; Bekkering, S.; Van Der Heijden, C.D.C.C.; Rodwell, L.; Bolboacă, S.D.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Netea, M.G.; Riksen, N.P.; Iancu, A.C. Intermediate monocytes are associated with the first major adverse cardiovascular event in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 2024, 400, 131780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Yoshida, N.; Shinke, T.; Otake, H.; Kuroda, M.; Sakaguchi, K.; Hirota, Y.; Toba, T.; Takahashi, H.; Terashita, D.; et al. Impact of CD14++CD16+ monocytes on coronary plaque vulnerability assessed by optical coherence tomography in coronary artery disease patients. Atherosclerosis 2018, 269, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöger, J.L.; Gijbels, M.J.J.; Van Der Velden, S.; Manca, M.; Van Der Loos, C.M.; Biessen, E.A.L.; Daemen, M.J.A.P.; Lutgens, E.; De Winther, M.P.J. Distribution of macrophage polarization markers in human atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2012, 225, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, F.; Liu, J.; Li, M.; Zhao, L. M2 Macrophages as a Potential Target for Antiatherosclerosis Treatment. Neural Plast. 2019, 2019, 6724903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, R.; Cioni, G.; Ricci, I.; Miranda, M.; Gori, A.M. Thrombosis and Acute coronary syndrome. Thromb. Res. 2012, 129, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahagi, K.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Lutter, C.; Mori, H.; Romero, M.E.; Finn, A.V.; Virmani, R. Pathology of Human Coronary and Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis and Vascular Calcification in Diabetes Mellitus. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmanik, M.; Chatrou, M.; Van Gorp, R.; Akbulut, A.; Willems, B.; Schmidt, H.; Van Eys, G.; Bochaton-Piallat, M.-L.; Proudfoot, D.; Biessen, E.; et al. Reactive Oxygen-Forming Nox5 Links Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypic Switching and Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Vascular Calcification. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 911–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Shao, C.; Jing, L.; Li, L.; Wang, Z. Role of Macrophages in the Progression and Regression of Vascular Calcification. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, M.; Park, S.-J.; Dauerman, H.L.; Uemura, S.; Kim, J.-S.; Di Mario, C.; Johnson, T.W.; Guagliumi, G.; Kastrati, A.; Joner, M.; et al. Optical coherence tomography in coronary atherosclerosis assessment and intervention. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 684–703, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgoglione, F.L.; Denegri, A.; Russo, M.; Calvieri, C.; Benatti, G.; Niccoli, G. Intracoronary Imaging of Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque: From Assessment of Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Therapeutic Implication. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurgoglione, F.L.; Solinas, E.; Pfleiderer, B.; Vezzani, A.; Niccoli, G. Coronary atherosclerotic plaque phenotype and physiopathologic mechanisms: Is there an influence of sex? Insights from intracoronary imaging. Atherosclerosis 2023, 384, 117273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, D.; Usui, E.; Vergallo, R.; Kinoshita, D.; Suzuki, K.; Niida, T.; Covani, M.; McNulty, I.; Lee, H.; Otake, H.; et al. Relationship Between Coronary Artery Calcium Score and Vulnerability of Culprit Plaque Assessed by OCT in Patients With Established Coronary Artery Disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 18, e017099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakahara, T.; Dweck, M.R.; Narula, N.; Pisapia, D.; Narula, J.; Strauss, H.W. Coronary Artery Calcification: From Mechanism to Molecular Imaging. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 10, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, D.; Kinoshita, D.; Suzuki, K.; Niida, T.; Yuki, H.; McNulty, I.; Lee, H.; Otake, H.; Shite, J.; Ferencik, M.; et al. Coronary spotty calcification, compared with macro calcification, is associated with a higher level of vascular inflammation and plaque vulnerability in patients with stable angina. Atherosclerosis 2025, 405, 119237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Gurgoglione, F.L.; Russo, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Torlai Triglia, L.; Foschi, M.; Vigna, C.; Vergallo, R.; Montone, R.A.; Benedetto, U.; et al. Coronary Artery Disease and Atherosclerosis in Other Vascular Districts: Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Atherosclerotic Plaque Features. Life 2025, 15, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author, Date, Reference | Study Design | SGLT2i Therapy | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelial Cells | |||

| Semo, 2023 [20] | Primary human monocytes, HUVECs, HCAECs, HPECs under hyperglycemia | Empagliflozin 100 ng/mL | Restored PlGF-1 signaling in monocytes and VEGF-A pathway in ECs (in vitro study) |

| Li, 2021 [21] | HCAECs exposed to 10% stretch | Empagliflozin 1 μM, Dapagliflozin 1 μM, Canagliflozin 3 μM | Reduced stretch-induced ROS production and improved barrier integrity (in vitro study) |

| Pawlos, 2023 [22] | HUVECs exposed to 25-hydroxycholesterol (10 μg/mL) | Empagliflozin 1 μM, Dapagliflozin 1 μM, Canagliflozin 1 μM | Restored endothelial integrity and VE-cadherin expression (in vitro study) |

| Lin, 2025 [24] | HUVECs exposed to high glucose | Dapagliflozin 1–10 μM | Reduced EC autophagy (in vitro study) |

| Ganbaatar, 2020 [25] | Male streptozotocin-induced diabetic ApoE−/− mice | Empagliflozin 20 mg/kg/day orally administered | Improved acetylcholine-induced vasodilation; reduced oxidative stress (in vitro study) |

| Guo, 2023 [23] | hiPSC-derived ECs carrying ALDH2 variant | Empagliflozin 10 mg/kg/day intraperitoneally administered | Reduced oxidative stress, decreased endothelial barrier permeability (in vitro study) |

| Monocytes/macrophages pathways | |||

| Terasaki, 2015 [26] | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic ApoE−/− and db/db mice | Dapagliflozin or Ipragliflozin 1.0 mg/kg/day orally administered | Reduced macrophage infiltration in diabetic mice (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Terasaki, 2017 [27] | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic ApoE−/− and db/db mice | Ipragliflozin 1.0 mg/kg/day orally administered | Reduced foam cell formation (animal model: peritoneal macrophages) |

| Pennig, 2019 [28] | LDLR/SRB1 streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice | Empagliflozin 35 mg/kg/day orally administered | Decreased lipid content and CD68+ macrophages (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Chen, 2023 [29] | Intraplaque macrophages and female ApoE−/− mice | Canagliflozin 10 μM (in vitro) or 10 mg/kg/day orally | Promoted autophagy (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Chen, 2022 [30] | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic ApoE−/− mice | Dapagliflozin 25 mg/kg/day orally administered | Increased collagen and decreased macrophages (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Inflammation pathways | |||

| Leng, 2016 [31] | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic and non-diabetic ApoE−/− mice | Dapagliflozin 1.0 mg/kg/day intragastrically administered | Reduced macrophage infiltration and interleukin production (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Nakatsu, 2017 [32] | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic and non-diabetic ApoE−/− mice | Luseogliflozin (dose not specified) | Reduced TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, MMP-2, MMP-9 release in diabetic mice (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Han, 2017 [33] | ApoE−/− mice | Empagliflozin 1 or 3 mg/kg | Reduced TNF-α, IL-6, MCP-1 levels in serum and adipose tissue (animal model: aortic arch and aortic valve area) |

| Lee, 2020 [34] | Rabbit model of atherosclerosis from abdominal aorta | Dapagliflozin 1 mg/kg/day orally administered | Reduced macrophage infiltration; increased M2 macrophage subtype (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Iwamoto, 2022 [35] | Streptozotocin-induced diabetic and non-diabetic ApoE−/− mice | Diet containing 0.005% tofogliflozin | Reduced IL-1β and IL-6 expression in peritoneal macrophages (animal model: heart and aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Xu, 2024 [36] | In vitro macrophages, HASMCs, HUVECs | Empagliflozin 50 μM | Induced autophagy via AMPK pathway (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Lin, 2014 [37] | Male db/db mice | Diet containing 0.03% Empagliflozin | Reduced cardiac fibrosis and coronary wall thickening (animal model: heart and aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Thrombosis | |||

| Spigoni, 2020 [38] | Human myeloid cells and platelets exposed to stearic acid | Empagliflozin or Dapagliflozin 1–100 μM | Reduced platelet activation (in vitro study: peripheral blood of healthy subjects) |

| Liberale, 2023 [40] | C57BL/6 mice treated with LPS before carotid thrombosis | Empagliflozin 25 mg/kg | No effect on platelet aggregation, PAI-1, or tissue factor expression (in vitro study: C57BL/6 mice) |

| Vascular Calcification | |||

| Chen, 2023 [41] | Mouse aortic cells with in vitro–induced calcification | Canagliflozin 5–20 μM | Reduced arterial calcification in VSMCs (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Wu, 2024 [42] | C57BL/6J mice | Dapagliflozin 5–20 μM | Reduced calcification in VSMCs and in vivo aorta (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| Li, 2024 [43] | C57BL/6J mice | Dapagliflozin 2.5–10 μM | Inhibited vascular calcification (animal model: aortic atherosclerotic lesions) |

| First Author, Date, Reference | Study Design | SGLT2i Therapy | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seecheran, 2021 [39] | Diabetic patients with stable CAD; platelet function assessed with VerifyNow™ P2Y12 assay | Dapagliflozin | Significantly reduced P2Y12 reactivity (reaction units decreased by 20%) |

| Sardu, 2023 [44] | Diabetic patients with non-obstructive multivessel stable CAD | Commercially available SGLT2i, orally administered | Reduced macrophage grade and lipid arc; increased fibrous cap thickness (FCT) on OCT; lower MACE rate at 1-year follow-up |

| Kurozumi, 2024 [45] | Diabetic patients with ACS | Commercially available SGLT2i, orally administered | Increased FCT; reduced lipid arc; lower MACE and revascularization rates at follow-up |

| Zhang, 2024 [46] | Diabetic patients undergoing ≥2 coronary CT angiographies | Dapagliflozin (5 mg/day), Empagliflozin (10 mg/day), or Canagliflozin (100 mg/day) | Significantly reduced total plaque volume, primarily due to reduction in non-calcified plaque volume |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gurgoglione, F.L.; Covani, M.; Torlai Triglia, L.; Benatti, G.; Donelli, D.; Bianconcini, M.; Solinas, E.; Tadonio, I.; Denegri, A.; De Gregorio, M.; et al. The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitors on Atherogenesis: A Systematic Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence. Life 2025, 15, 1784. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111784

Gurgoglione FL, Covani M, Torlai Triglia L, Benatti G, Donelli D, Bianconcini M, Solinas E, Tadonio I, Denegri A, De Gregorio M, et al. The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitors on Atherogenesis: A Systematic Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence. Life. 2025; 15(11):1784. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111784

Chicago/Turabian StyleGurgoglione, Filippo Luca, Marco Covani, Laura Torlai Triglia, Giorgio Benatti, Davide Donelli, Michele Bianconcini, Emilia Solinas, Iacopo Tadonio, Andrea Denegri, Mattia De Gregorio, and et al. 2025. "The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitors on Atherogenesis: A Systematic Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence" Life 15, no. 11: 1784. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111784

APA StyleGurgoglione, F. L., Covani, M., Torlai Triglia, L., Benatti, G., Donelli, D., Bianconcini, M., Solinas, E., Tadonio, I., Denegri, A., De Gregorio, M., Dallaglio, G., Dei Cas, A., Bonadonna, R. C., Vignali, L., & Niccoli, G. (2025). The Impact of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT-2) Inhibitors on Atherogenesis: A Systematic Review of Experimental and Clinical Evidence. Life, 15(11), 1784. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111784