The Converging Roles of Nucleases and Helicases in Genome Maintenance and the Aging Process

Abstract

1. DNA Damage: A Fundamental Driver of the Aging Process

2. Progeroid Syndromes: Human Models of Accelerated Aging from DDR Defects

3. Mouse Models: Experimental Evidence Linking DDR Defects to Aging

4. Helicases and Nucleases: Divergent Mechanisms, Complementary Functions

5. The Genome Maintenance Network: An Interplay of Helicases and Nucleases

6. Epigenome–Genome Crosstalk: Helicases and Nucleases at the Chromatin Interface

7. From DNA Damage to Senescence: The Vicious Cycle of Stem Cell Exhaustion and Aging

8. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting the DDR–Aging Axis

9. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATM | Ataxia–Telangiectasia Mutated kinase |

| ATR | Ataxia–Telangiectasia and Rad3-related kinase |

| BER | Base excision repair |

| BRCA | Breast cancer susceptibility protein |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| DSB | Double-strand break |

| dHJ | Double Holliday junction |

| DNA-PKcs | DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit |

| ERCC | Excision repair cross-complementation group |

| EXO1 | Exonuclease 1 |

| FA | Fanconi anemia |

| FANCM | Fanconi anemia complementation group M protein |

| HhH2 | Helix–hairpin–helix domain |

| HR | Homologous recombination |

| HRDC | Helicase and RNase D C-terminal domain |

| MRN | MRE11–RAD50–NBS1 complex |

| MRE11 | Meiotic recombination 11 protein |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stem cell |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| NER | Nucleotide excision repair |

| NHEJ | Non-homologous end joining |

| NSC | Neural stem cell |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| PD-(D/E)XK | Conserved catalytic motif of nuclease family |

| POLG | DNA polymerase γ |

| RPA | Replication protein A |

| RQC | RecQ C-terminal domain |

| RTEL1 | Regulator of telomere elongation helicase 1 |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SF1–SF6 | Helicase superfamilies 1–6 |

| TFIIH | Transcription factor IIH complex |

| WRN | Werner syndrome helicase |

| XPA | Xeroderma Pigmentosum group A protein |

| XPB | Xeroderma Pigmentosum group B helicase |

| XPC | Xeroderma Pigmentosum group C protein |

| XPD | Xeroderma Pigmentosum group D helicase |

| XPF | Xeroderma Pigmentosum group F endonuclease (ERCC4) |

| XPG | Xeroderma Pigmentosum group G endonuclease (ERCC5) |

References

- Harman, D. The aging process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 7124–7128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Baker, D.J.; Van Deursen, J.M. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: From mechanisms to therapy. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1424–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Hickson, L.J.; Eirin, A.; Kirkland, J.L.; Lerman, L.O. Cellular senescence: The good, the bad and the unknown. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, N.; Mann, D.J.; Hara, E. Cellular senescence: Its role in tumor suppression and aging. Cancer Sci. 2009, 100, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Kawamoto, S.; Ohtani, N.; Hara, E. Impact of senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its potential as a therapeutic target for senescence-associated diseases. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bont, R. Endogenous DNA damage in humans: A review of quantitative data. Mutagenesis 2004, 19, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Liew, W.-P.-P. Nutrients and Oxidative Stress: Friend or Foe? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 9719584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, M.; Henpita, C.; Vyas, R.; Soto-Palma, C.; Robbins, P.; Niedernhofer, L. DNA damage—How and why we age? eLife 2021, 10, e62852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, W.P.; Thomas, A.D.; Kaina, B. DNA damage and the balance between survival and death in cancer biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sottoriva, A.; Barnes, C.P.; Graham, T.A. Catch my drift? Making sense of genomic intra-tumour heterogeneity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Rev. Cancer 2017, 1867, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGranahan, N.; Swanton, C. Clonal Heterogeneity and Tumor Evolution: Past, Present, and the Future. Cell 2017, 168, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Albert Zhou, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, J. Evolving insights: How DNA repair pathways impact cancer evolution. Cancer Biol. Med. 2020, 17, 805–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.-B.S.; Elledge, S.J. The DNA damage response: Putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature 2000, 408, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbunova, V.; Seluanov, A.; Mao, Z.; Hine, C. Changes in DNA repair during aging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7466–7474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickoloff, J.A.; Sharma, N.; Taylor, L.; Allen, S.J.; Hromas, R. Nucleases and Co-Factors in DNA Replication Stress Responses. DNA 2022, 2, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, C.L.; Cau, P.; Lévy, N. Molecular bases of progeroid syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, R151–R161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.M. Genetic Modulation of Senescent Phenotypes in Homo sapiens. Cell 2005, 120, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, M.X.R.; Ong, P.F.; Dreesen, O. Premature aging syndromes: From patients to mechanism. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2019, 96, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakura, J.; Ye, L.; Morishima, A.; Kohara, K.; Miki, T. Helicases and aging. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2000, 57, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketkar, A.; Voehler, M.; Mukiza, T.; Eoff, R.L. Residues in the RecQ C-Terminal Domain of the Human Werner Syndrome Helicase Are Involved in Unwinding G-Quadruplex DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 3154–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamanna, R.A.; Croteau, D.L.; Lee, J.-H.; Bohr, V.A. Recent Advances in Understanding Werner Syndrome. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Multani, A.S.; Cabrera, N.G.; Naylor, M.L.; Laud, P.; Lombard, D.; Pathak, S.; Guarente, L.; DePinho, R.A. Essential role of limiting telomeres in the pathogenesis of Werner syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paccosi, E.; Guzzon, D.; Proietti-De-Santis, L. Genetic and epigenetic insights into Werner Syndrome. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababou, M. Bloom syndrome and the underlying causes of genetic instability. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2021, 133, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, H.; Chacon, A.H.; Choudhary, S.; McLeod, M.P.; Meshkov, L.; Nouri, K.; Izakovic, J. Bloom syndrome. Int. J. Dermatol. 2014, 53, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciejczyk, M.; Mikoluc, B.; Pietrucha, B.; Heropolitanska-Pliszka, E.; Pac, M.; Motkowski, R.; Car, H. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial abnormalities and antioxidant defense in Ataxia-telangiectasia, Bloom syndrome and Nijmegen breakage syndrome. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Hickson, I.D. The Bloom’s syndrome helicase suppresses crossing over during homologous recombination. Nature 2003, 426, 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluźniak, W.; Wokołorczyk, D.; Rusak, B.; Huzarski, T.; Kashyap, A.; Stempa, K.; Rudnicka, H.; Jakubowska, A.; Szwiec, M.; Morawska, S.; et al. Inherited Variants in BLM and the Risk and Clinical Characteristics of Breast Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qin, W.; Wang, H.; Lin, Z.; Tang, Z.; Xu, Z. Novel pathogenic variants in the RECQL4 gene causing Rothmund-Thomson syndrome in three Chinese patients. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitao, S.; Shimamoto, A.; Goto, M.; Miller, R.W.; Smithson, W.A.; Lindor, N.M.; Furuichi, Y. Mutations in RECQL4 cause a subset of cases of Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1999, 22, 82–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larizza, L.; Roversi, G.; Volpi, L. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Jin, W.; Wang, L.L. Aging in Rothmund-Thomson syndrome and related RECQL4 genetic disorders. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 33, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, D.J.; Di Lazzaro Filho, R.; Bertola, D.R.; Hoch, N.C. Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, a disorder far from solved. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1296409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnasamy, V.; Navaneethakrishnan, S.; Sirisena, N.D.; Grüning, N.-M.; Brandau, O.; Thirunavukarasu, K.; Dagnall, C.L.; McReynolds, L.J.; Savage, S.A.; Dissanayake, V.H.W. Dyskeratosis congenita with a novel genetic variant in the DKC1 gene: A case report. BMC Med. Genet. 2018, 19, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, S.; Vulliamy, T.; Copplestone, A.; Gluckman, E.; Mason, P.; Dokal, I. Dyskeratosis Congenita (DC) Registry: Identification of new features of DC. Br. J. Haematol. 1998, 103, 990–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwan, M.; Dokal, I. Dyskeratosis congenita, stem cells and telomeres. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Basis Dis. 2009, 1792, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavasoli, A.R.; Kaki, A.; Ganji, M.; Kahani, S.M.; Radmehr, F.; Mohammadi, P.; Heidari, M.; Ashrafi, M.R.; Lewis, K.S. Trichothiodystrophy due to ERCC2 Variants: Uncommon Contributor to Progressive Hypomyelinating Leukodystrophy. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2025, 13, e70067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, E.; Egly, J.-M. Trichothiodystrophy, a transcription syndrome. Trends Genet. 2001, 17, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, M.; Botta, E.; Lanzafame, M.; Orioli, D. Trichothiodystrophy: From basic mechanisms to clinical implications. DNA Repair 2010, 9, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dri, J.; Dos Santos, E.; Fernandez, A.; Galdeano, F.; Guillamondegui, M.J.; Gatica, C. Trichothiodystrophy type 3 with a mutation in the GTF2H5 gene: A case report in Argentina. Arch. Argent. Pediatr. 2025, 123, e202410522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeda, G.; Eveno, E.; Donker, I.; Vermeulen, W.; Chevallier-Lagente, O.; Taïeb, A.; Stary, A.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.; Mezzina, M.; Sarasin, A. A mutation in the XPB/ERCC3 DNA repair transcription gene, associated with trichothiodystrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 60, 320–329. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, M.C.; Emmert, S.; Boeckmann, L. Xeroderma Pigmentosum: Gene Variants and Splice Variants. Genes 2021, 12, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizza, E.R.H.; DiGiovanna, J.J.; Khan, S.G.; Tamura, D.; Jeskey, J.D.; Kraemer, K.H. Xeroderma Pigmentosum: A Model for Human Premature Aging. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.K.; Barankin, B.; Lam, J.M.; Leong, K.F.; Hon, K.L. Xeroderma pigmentosum: An updated review. Drugs Context 2022, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berneburgl, M.; Lehmann, A.R. 3 Xeroderma pigmentosum and related disorders: Defects in DNA repair and transcription. In Advances in Genetics; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 43, pp. 71–102. ISBN 978-0-12-017643-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer, K.H.; Patronas, N.J.; Schiffmann, R.; Brooks, B.P.; Tamura, D.; DiGiovanna, J.J. Xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy and Cockayne syndrome: A complex genotype–phenotype relationship. Neuroscience 2007, 145, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, R.; Kim, R.; Neitzel, H.; Demuth, I.; Chrzanowska, K.; Seemanova, E.; Faber, R.; Digweed, M.; Voss, R.; Jäger, K.; et al. Telomere attrition and dysfunction: A potential trigger of the progeroid phenotype in nijmegen breakage syndrome. Aging 2020, 12, 12342–12375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrzanowska, K.H.; Gregorek, H.; Dembowska-Bagińska, B.; Kalina, M.A.; Digweed, M. Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2012, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiesco-Roa, M.O.; Giri, N.; McReynolds, L.J.; Best, A.F.; Alter, B.P. Genotype-phenotype associations in Fanconi anemia: A literature review. Blood Rev. 2019, 37, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, R.A.; Nieminuszczy, J.; Shah, F.; Langton, J.; Lopez Martinez, D.; Liang, C.-C.; Cohn, M.A.; Gibbons, R.J.; Deans, A.J.; Niedzwiedz, W. The Fanconi Anemia Pathway Maintains Genome Stability by Coordinating Replication and Transcription. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Nandi, S. DNA damage response and cancer therapeutics through the lens of the Fanconi Anemia DNA repair pathway. Cell Commun. Signal. 2017, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosh, R.M.; Bellani, M.; Liu, Y.; Seidman, M.M. Fanconi Anemia: A DNA repair disorder characterized by accelerated decline of the hematopoietic stem cell compartment and other features of aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 33, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogliolo, M.; Schuster, B.; Stoepker, C.; Derkunt, B.; Su, Y.; Raams, A.; Trujillo, J.P.; Minguillón, J.; Ramírez, M.J.; Pujol, R.; et al. Mutations in ERCC4, Encoding the DNA-Repair Endonuclease XPF, Cause Fanconi Anemia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 92, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farah, R.A.; Nair, P.; Koueik, J.; Yammine, T.; Khalifeh, H.; Korban, R.; Collet, A.; Khayat, C.; Dubois-Denghien, C.; Chouery, E.; et al. Clinical and Genetic Features of Patients with Fanconi Anemia in Lebanon and Report on Novel Mutations in the FANCA and FANCG Genes. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 43, e727–e735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguado, J.; Gómez-Inclán, C.; Leeson, H.C.; Lavin, M.F.; Shiloh, Y.; Wolvetang, E.J. The hallmarks of aging in Ataxia-Telangiectasia. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 79, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiévet, A.; Bellanger, D.; Rieunier, G.; Dubois d’Enghien, C.; Sophie, J.; Calvas, P.; Carriere, J.; Anheim, M.; Castrioto, A.; Flabeau, O.; et al. Functional classification of ATM variants in ataxia-telangiectasia patients. Hum. Mutat. 2019, 40, 1713–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, K.R.; Watters, D.J. Neurodegeneration in ataxia-telangiectasia: Multiple roles of ATM kinase in cellular homeostasis. Dev. Dyn. 2018, 247, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidenheim, K.M.; Dickson, D.W.; Rapin, I. Neuropathology of Cockayne syndrome: Evidence for impaired development, premature aging, and neurodegeneration. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2009, 130, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso-Reis, R.; Madeira, C.R.; Brito, D.V.C.; Nóbrega, C. Insights into Cockayne Syndrome Type B: What Underlies Its Pathogenesis? Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, D.; Okamoto, N.; Kobayashi, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Kato, M.; Saitoh, S.; Kanemura, Y.; Takenouchi, T.; Yamada, M.; Nakato, D.; et al. Biallelic structural variants in three patients with ERCC8-related Cockayne syndrome and a potential pitfall of copy number variation analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Qiu, P.; Ji, H.; Ding, L.; Shi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, P.; Mei, L. Preimplantation genetic testing for Cockayne syndrome with a novel ERCC6 variant in a Chinese family. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1435622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cisneros, B.; García-Aguirre, I.; De Ita, M.; Arrieta-Cruz, I.; Rosas-Vargas, H. Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome: Cellular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives. Arch. Med. Res. 2023, 54, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalo, S.; Kreienkamp, R. DNA repair defects and genome instability in Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria Syndrome. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 34, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaffidi, P.; Misteli, T. Reversal of the cellular phenotype in the premature aging disease Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenni, V.; D’Apice, M.R.; Garagnani, P.; Columbaro, M.; Novelli, G.; Franceschi, C.; Lattanzi, G. Mandibuloacral dysplasia: A premature ageing disease with aspects of physiological ageing. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, G.; Muchir, A.; Sangiuolo, F.; Helbling-Leclerc, A.; D’Apice, M.R.; Massart, C.; Capon, F.; Sbraccia, P.; Federici, M.; Lauro, R.; et al. Mandibuloacral Dysplasia Is Caused by a Mutation in LMNA-Encoding Lamin A/C. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002, 71, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simha, V.; Agarwal, A.K.; Oral, E.A.; Fryns, J.-P.; Garg, A. Genetic and Phenotypic Heterogeneity in Patients with Mandibuloacral Dysplasia-Associated Lipodystrophy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 2821–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, R.L. Mouse Models of Human Disease: An Evolutionary Perspective. Evol. Med. Public Health 2016, 2016, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhooren, V.; Libert, C. The mouse as a model organism in aging research: Usefulness, pitfalls and possibilities. Ageing Res. Rev. 2013, 12, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurkar, A.U.; Niedernhofer, L.J. Comparison of mice with accelerated aging caused by distinct mechanisms. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 68, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkema, L.; Youssef, S.A.; De Bruin, A. Pathology of Mouse Models of Accelerated Aging. Vet. Pathol. 2016, 53, 366–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, V. Rising from the RecQ-age: The role of human RecQ helicases in genome maintenance. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2008, 33, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, K.; Parras, A.; Picó, S.; Rechsteiner, C.; Haghani, A.; Brooke, R.; Mrabti, C.; Schoenfeldt, L.; Horvath, S.; Ocampo, A. DNA repair-deficient premature aging models display accelerated epigenetic age. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kieckhaefer, J.E.; Cao, K. Mouse models of laminopathies. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T. Senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM): A biogerontological resource in aging research. Neurobiol. Aging 1999, 20, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, N.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y. Induction of Accelerated Aging in a Mouse Model. Cells 2022, 11, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massip, L.; Garand, C.; Turaga, R.V.N.; Deschênes, F.; Thorin, E.; Lebel, M. Increased insulin, triglycerides, reactive oxygen species, and cardiac fibrosis in mice with a mutation in the helicase domain of the Werner syndrome gene homologue. Exp. Gerontol. 2006, 41, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumailley, L.; Garand, C.; Dubois, M.J.; Johnson, F.B.; Marette, A.; Lebel, M. Metabolic and Phenotypic Differences between Mice Producing a Werner Syndrome Helicase Mutant Protein and Wrn Null Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, D.B.; Beard, C.; Johnson, B.; Marciniak, R.A.; Dausman, J.; Bronson, R.; Buhlmann, J.E.; Lipman, R.; Curry, R.; Sharpe, A.; et al. Mutations in the WRN Gene in Mice Accelerate Mortality in a p53-Null Background. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 3286–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebel, M.; Leder, P. A deletion within the murine Werner syndrome helicase induces sensitivity to inhibitors of topoisomerase and loss of cellular proliferative capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 13097–13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multani, A.S.; Chang, S. WRN at telomeres: Implications for aging and cancer. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, K.H.; Risinger, M.A.; Kordich, J.J.; Sanz, M.M.; Straughen, J.E.; Slovek, L.E.; Capobianco, A.J.; German, J.; Boivin, G.P.; Groden, J. Enhanced Tumor Formation in Mice Heterozygous for Blm Mutation. Science 2002, 297, 2051–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, M.; Chung, Y.-J.; Howat, W.J.; Harrison, H.; McGinnis, R.; Hao, X.; McCafferty, J.; Fredrickson, T.N.; Bradley, A.; Morse, H.C. Irradiated Blm-deficient mice are a highly tumor prone model for analysis of a broad spectrum of hematologic malignancies. Leuk. Res. 2010, 34, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Fang, E.F.; Sykora, P.; Kulikowicz, T.; Zhang, Y.; Becker, K.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Senescence induced by RECQL4 dysfunction contributes to Rothmund–Thomson syndrome features in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoki, Y. Growth retardation and skin abnormalities of the Recql4-deficient mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 2293–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, A.; Kieu, T.; Robbins, P.D. The Ercc 1-/Δ mouse model of accelerated senescence and aging for identification and testing of novel senotherapeutic interventions. Aging 2020, 12, 24481–24483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, N.J.; Sacco, J.J.; Brownstein, D.G.; Gillingwater, T.H.; Melton, D.W. A neurological phenotype in mice with DNA repair gene Ercc1 deficiency. DNA Repair 2008, 7, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhoorn, S.; Uittenboogaard, L.M.; Jaarsma, D.; Vermeij, W.P.; Tresini, M.; Weymaere, M.; Menoni, H.; Brandt, R.M.C.; De Waard, M.C.; Botter, S.M.; et al. Cell-Autonomous Progeroid Changes in Conditional Mouse Models for Repair Endonuclease XPG Deficiency. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; De Wit, J.; Van Steeg, H.; Berg, R.J.W.; Morreau, H.; Visser, P.; Lehmann, A.R.; Duran, M.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J.; Weeda, G. A Mouse Model for the Basal Transcription/DNA Repair Syndrome Trichothiodystrophy. Mol. Cell 1998, 1, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, C.; Hirotsune, S.; Paylor, R.; Liyanage, M.; Eckhaus, M.; Collins, F.; Shiloh, Y.; Crawley, J.N.; Ried, T.; Tagle, D.; et al. Atm-Deficient Mice: A Paradigm of Ataxia Telangiectasia. Cell 1996, 86, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putti, S.; Giovinazzo, A.; Merolle, M.; Falchetti, M.L.; Pellegrini, M. ATM Kinase Dead: From Ataxia Telangiectasia Syndrome to Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menolfi, D.; Zha, S. ATM, ATR and DNA-PKcs kinases—The lessons from the mouse models: Inhibition ≠ deletion. Cell Biosci. 2020, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarsma, D.; Van Der Pluijm, I.; Van Der Horst, G.T.J.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J. Cockayne syndrome pathogenesis: Lessons from mouse models. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2013, 134, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waard, H.; De Wit, J.; Andressoo, J.-O.; Van Oostrom, C.T.M.; Riis, B.; Weimann, A.; Poulsen, H.E.; Van Steeg, H.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J.; Van Der Horst, G.T.J. Different Effects of CSA and CSB Deficiency on Sensitivity to Oxidative DNA Damage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 7941–7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Burg, M.; Van Dongen, J.J.; Van Gent, D.C. DNA-PKcs deficiency in human: Long predicted, finally found. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 9, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussenzweig, A.; Sokol, K.; Burgman, P.; Li, L.; Li, G.C. Hypersensitivity of Ku80-deficient cell lines and mice to DNA damage: The effects of ionizing radiation on growth, survival, and development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 13588–13593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, D.-S.; Vogel, H.; Willerford, D.M.; Sands, A.T.; Platt, K.A.; Hasty, P. Analysis of ku80 -Mutant Mice and Cells with Deficient Levels of p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 3772–3780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Parmar, K.; D’Andrea, A.; Niedernhofer, L.J. Mouse models of Fanconi anemia. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2009, 668, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Vrugt, H.J.; Koomen, M.; Bakker, S.; Berns, M.A.D.; Cheng, N.C.; Van Der Valk, M.A.; De Vries, Y.; Rooimans, M.A.; Oostra, A.B.; Hoatlin, M.E.; et al. Evidence for complete epistasis of null mutations in murine Fanconi anemia genes Fanca and Fancg. DNA Repair 2011, 10, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaghini, A.; Sarli, G.; Barboni, C.; Sanapo, M.; Pellegrino, V.; Diana, A.; Linta, N.; Rambaldi, J.; D’Apice, M.R.; Murdocca, M.; et al. Long term breeding of the Lmna G609G progeric mouse: Characterization of homozygous and heterozygous models. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 130, 110784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Andres, D.A.; Spielmann, H.P.; Young, S.G.; Fong, L.G. Progerin elicits disease phenotypes of progeria in mice whether or not it is farnesylated. J. Clin. Invest. 2008, 118, 3291–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounkes, L.C.; Kozlov, S.; Hernandez, L.; Sullivan, T.; Stewart, C.L. A progeroid syndrome in mice is caused by defects in A-type lamins. Nature 2003, 423, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espada, J.; Varela, I.; Flores, I.; Ugalde, A.P.; Cadiñanos, J.; Pendás, A.M.; Stewart, C.L.; Tryggvason, K.; Blasco, M.A.; Freije, J.M.P.; et al. Nuclear envelope defects cause stem cell dysfunction in premature-aging mice. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 181, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifunovic, A.; Wredenberg, A.; Falkenberg, M.; Spelbrink, J.N.; Rovio, A.T.; Bruder, C.E.; Bohlooly-Y, M.; Gidlöf, S.; Oldfors, A.; Wibom, R.; et al. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 2004, 429, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.C.; Remmen, H.V. The mitochondrial theory of aging: Insight from transgenic and knockout mouse models. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, T.; Hosokawa, M.; Higuchi, K. Senescence-accelerated mouse (SAM): A novel murine model of senescence. Exp. Gerontol. 1997, 32, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azman, K.F.; Zakaria, R. D-Galactose-induced accelerated aging model: An overview. Biogerontology 2019, 20, 763–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.-C.; Liu, J.-H.; Wu, R.-Y. Establishment of the mimetic aging effect in mice caused by D-galactose. Biogerontology 2003, 4, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Fan, S. Total body irradiation induced mouse small intestine senescence as a late effect. J. Radiat. Res. 2019, 60, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Schulte, B.A.; LaRue, A.C.; Ogawa, M.; Zhou, D. Total body irradiation selectively induces murine hematopoietic stem cell senescence. Blood 2006, 107, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackert-Bicknell, C.L.; Anderson, L.C.; Sheehan, S.; Hill, W.G.; Chang, B.; Churchill, G.A.; Chesler, E.J.; Korstanje, R.; Peters, L.L. Aging Research Using Mouse Models. Curr. Protoc. Mouse Biol. 2015, 5, 95–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kõks, S.; Dogan, S.; Tuna, B.G.; González-Navarro, H.; Potter, P.; Vandenbroucke, R.E. Mouse models of ageing and their relevance to disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2016, 160, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, B.; Keck, J.L. Grip it and rip it: Structural mechanisms of DNA helicase substrate binding and unwinding. Protein Sci. 2014, 23, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. Nucleases: Diversity of structure, function and mechanism. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2011, 44, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, M.R.; Dillingham, M.S.; Wigley, D.B. Structure and Mechanism of Helicases and Nucleic Acid Translocases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007, 76, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alicia, K.B. Superfamily 2 helicases. Front. Biosci. 2012, 17, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, K.A.; Gangloff, S.; Rothstein, R. The RecQ DNA Helicases in DNA Repair. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2010, 44, 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; Cao, Z.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y. Targeting the Werner syndrome protein in microsatellite instability cancers: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 25, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiu, T.-C.; Tu, J.; Cheung, H.-H. An overview of RecQ helicases and related diseases. Aging 2025, 17, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortone, G.; Graewert, M.A.; Kanade, M.; Longo, A.; Hegde, R.; González-Magaña, A.; Chaves-Arquero, B.; Blanco, F.J.; Napolitano, L.M.R.; Onesti, S. Structural and biochemical characterization of the C-terminal region of the human RTEL 1 helicase. Protein Sci. 2024, 33, e5093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, J.O.; Tainer, J.A. XPB and XPD helicases in TFIIH orchestrate DNA duplex opening and damage verification to coordinate repair with transcription and cell cycle via CAK kinase. DNA Repair 2011, 10, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbouche, L.; Murphy, V.J.; Gao, J.; van Twest, S.; Sobinoff, A.P.; Auweiler, K.M.; Pickett, H.A.; Bythell-Douglas, R.; Deans, A.J. Mechanism of structure-specific DNA binding by the FANCM branchpoint translocase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 11029–11044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enzlin, J.H. The active site of the DNA repair endonuclease XPF-ERCC1 forms a highly conserved nuclease motif. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 2045–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schärer, O.D. XPG: Its Products and Biological Roles. In Molecular Mechanisms of Xeroderma Pigmentosum; Ahmad, S.I., Hanaoka, F., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 637, pp. 83–92. ISBN 978-0-387-09598-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tomimatsu, N.; Mukherjee, B.; Deland, K.; Kurimasa, A.; Bolderson, E.; Khanna, K.K.; Burma, S. Exo1 plays a major role in DNA end resection in humans and influences double-strand break repair and damage signaling decisions. DNA Repair 2012, 11, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracker, T.H.; Petrini, J.H.J. The MRE11 complex: Starting from the ends. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Meng, Y.; Campbell, J.L.; Shen, B. Multiple roles of DNA2 nuclease/helicase in DNA metabolism, genome stability and human diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

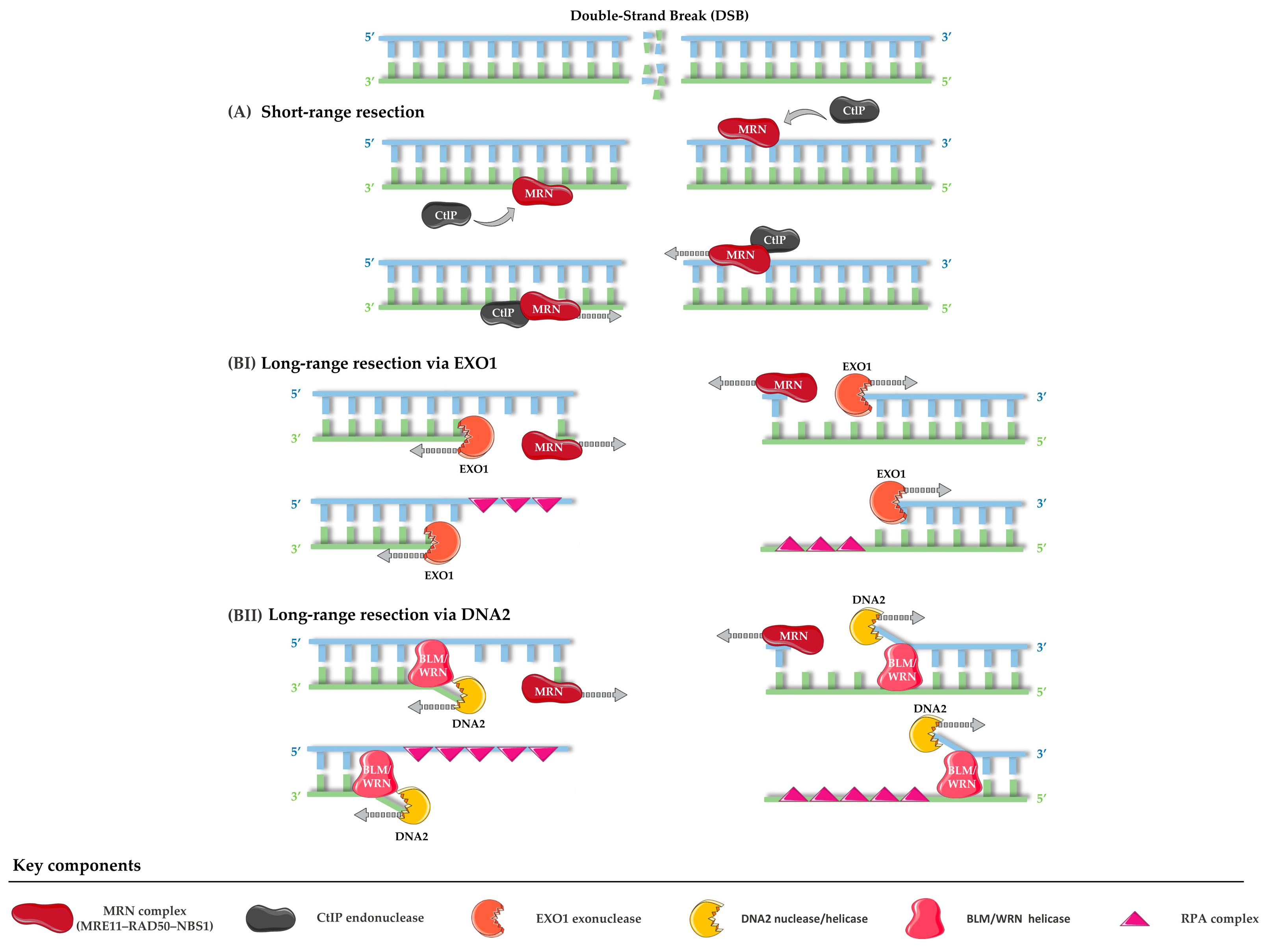

- Mimitou, E.P.; Symington, L.S. Nucleases and helicases take center stage in homologous recombination. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2009, 34, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ehmsen, K.T.; Heyer, W.-D.; Morrical, S.W. Presynaptic filament dynamics in homologous recombination and DNA repair. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 46, 240–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, J.; Hickson, I.D. Replication fork barriers to study site-specific DNA replication perturbation. DNA Repair 2024, 141, 103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.L.; Orr-Weaver, T.L. Replication fork instability and the consequences of fork collisions from rereplication. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 2241–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, M.; Cortez, D.; Lopes, M. The plasticity of DNA replication forks in response to clinically relevant genotoxic stress. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, L.M.; Schaffer, E.D.; Fuchs, K.F.; Datta, A.; Brosh, R.M. Replication stress as a driver of cellular senescence and aging. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelsen, K.J.; Lopes, M. Replication fork reversal in eukaryotes: From dead end to dynamic response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, D. Preventing replication fork collapse to maintain genome integrity. DNA Repair 2015, 32, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinet, A.; Lemaçon, D.; Vindigni, A. Replication Fork Reversal: Players and Guardians. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 830–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bétous, R.; Couch, F.B.; Mason, A.C.; Eichman, B.F.; Manosas, M.; Cortez, D. Substrate-Selective Repair and Restart of Replication Forks by DNA Translocases. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1958–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, A.; Moiani, D.; Arvai, A.S.; Perry, J.; Harding, S.M.; Genois, M.-M.; Maity, R.; van Rossum-Fikkert, S.; Kertokalio, A.; Romoli, F.; et al. DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathway Choice Is Directed by Distinct MRE11 Nuclease Activities. Mol. Cell 2014, 53, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangavel, S.; Berti, M.; Levikova, M.; Pinto, C.; Gomathinayagam, S.; Vujanovic, M.; Zellweger, R.; Moore, H.; Lee, E.H.; Hendrickson, E.A.; et al. DNA2 drives processing and restart of reversed replication forks in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 208, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasero, P.; Vindigni, A. Nucleases Acting at Stalled Forks: How to Reboot the Replication Program with a Few Shortcuts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2017, 51, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlacher, K.; Christ, N.; Siaud, N.; Egashira, A.; Wu, H.; Jasin, M. Double-Strand Break Repair-Independent Role for BRCA2 in Blocking Stalled Replication Fork Degradation by MRE11. Cell 2011, 145, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuzzi, G.; Marabitti, V.; Pichierri, P.; Franchitto, A. WRNIP 1 protects stalled forks from degradation and promotes fork restart after replication stress. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 1437–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Sung, P.; Zhao, X. Functions and regulation of the multitasking FANCM family of DNA motor proteins. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1777–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panday, A.; Willis, N.A.; Elango, R.; Menghi, F.; Duffey, E.E.; Liu, E.T.; Scully, R. FANCM regulates repair pathway choice at stalled replication forks. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 2428–2444.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanada, K.; Budzowska, M.; Modesti, M.; Maas, A.; Wyman, C.; Essers, J.; Kanaar, R. The structure-specific endonuclease Mus81–Eme1 promotes conversion of interstrand DNA crosslinks into double-strands breaks. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 4921–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Saada, A.; Lambert, S.A.E.; Carr, A.M. Preserving replication fork integrity and competence via the homologous recombination pathway. DNA Repair 2018, 71, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacaria, E.; Honda, M.; Franchitto, A.; Spies, M.; Pichierri, P. Physiological and Pathological Roles of RAD52 at DNA Replication Forks. Cancers 2020, 12, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Walker, G.C. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2017, 58, 235–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soniat, M.M.; Myler, L.R. Using the safety scissors: DNA resection regulation at DNA double-strand breaks and telomeres. DNA Repair 2025, 152, 103876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannavo, E.; Cejka, P. Sae2 promotes dsDNA endonuclease activity within Mre11–Rad50–Xrs2 to resect DNA breaks. Nature 2014, 514, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Chung, W.-H.; Shim, E.Y.; Lee, S.E.; Ira, G. Sgs1 Helicase and Two Nucleases Dna2 and Exo1 Resect DNA Double-Strand Break Ends. Cell 2008, 134, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueva, R.; Iliakis, G. Replication protein A: A multifunctional protein with roles in DNA replication, repair and beyond. NAR Cancer 2020, 2, zcaa022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzei, D.; Foiani, M. Maintaining genome stability at the replication fork. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.; Buechelmaier, E.; Belan, O.; Newton, M.; Vancevska, A.; Kaczmarczyk, A.; Takaki, T.; Rueda, D.S.; Powell, S.N.; Boulton, S.J. HELQ is a dual-function DSB repair enzyme modulated by RPA and RAD51. Nature 2022, 601, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, J.; Polasek-Sedlackova, H.; Lukas, J.; Somyajit, K. Homologous Recombination as a Fundamental Genome Surveillance Mechanism during DNA Replication. Genes 2021, 12, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harami, G.M.; Pálinkás, J.; Seol, Y.; Kovács, Z.J.; Gyimesi, M.; Harami-Papp, H.; Neuman, K.C.; Kovács, M. The toposiomerase IIIalpha-RMI1-RMI2 complex orients human Bloom’s syndrome helicase for efficient disruption of D-loops. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagge, J.; Petersen, K.V.; Karakus, S.N.; Nielsen, T.M.; Rask, J.; Brøgger, C.R.; Jensen, J.; Skouteri, M.; Carr, A.M.; Hendriks, I.A.; et al. TopBP1 coordinates DNA repair synthesis in mitosis via recruitment of the nuclease scaffold SLX4. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vriend, L.E.M.; Krawczyk, P.M. Nick-initiated homologous recombination: Protecting the genome, one strand at a time. DNA Repair 2017, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, L.N.; Brunet, A. The Aging Epigenome. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 728–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Najar, U.; Sedivy, J.M. Epigenetic Control of Aging. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; KH Yip, R.; Zhou, Z. Chromatin Remodeling, DNA Damage Repair and Aging. Curr. Genomics 2012, 13, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Zhou, X.; Tanaka, K.; Takahashi, A. Alteration in the chromatin landscape during the DNA damage response: Continuous rotation of the gear driving cellular senescence and aging. DNA Repair 2023, 131, 103572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsompana, M.; Buck, M.J. Chromatin accessibility: A window into the genome. Epigenetics Chromatin 2014, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, S.L.; Shipony, Z.; Greenleaf, W.J. Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristini, A.; Ricci, G.; Britton, S.; Salimbeni, S.; Huang, S.N.; Marinello, J.; Calsou, P.; Pommier, Y.; Favre, G.; Capranico, G.; et al. Dual Processing of R-Loops and Topoisomerase I Induces Transcription-Dependent DNA Double-Strand Breaks. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3167–3181.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Hendzel, M.J. The relationship between histone posttranslational modification and DNA damage signaling and repair. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2019, 95, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabin, J.; Giacomini, G.; Petit, E.; Polo, S.E. New facets in the chromatin-based regulation of genome maintenance. DNA Repair 2024, 140, 103702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, S.I.S. The molecular basis of heterochromatin assembly and epigenetic inheritance. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 1767–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansdorp, P.; Van Wietmarschen, N. Helicases FANCJ, RTEL1 and BLM Act on Guanine Quadruplex DNA in Vivo. Genes 2019, 10, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Takai, H.; de Lange, T. Telomeric 3′ Overhangs Derive from Resection by Exo1 and Apollo and Fill-In by POT1b-Associated CST. Cell 2012, 150, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballew, B.J.; Yeager, M.; Jacobs, K.; Giri, N.; Boland, J.; Burdett, L.; Alter, B.P.; Savage, S.A. Germline mutations of regulator of telomere elongation helicase 1, RTEL1, in Dyskeratosis congenita. Hum. Genet. 2013, 132, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, J.; Zhang, H.; Pongor, L.; Tang, S.-W.; Jo, U.; Moribe, F.; Ma, Y.; Tomita, M.; Pommier, Y. Chromatin Remodeling and Immediate Early Gene Activation by SLFN11 in Response to Replication Stress. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 4137–4151.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, P.; López-Contreras, A.J. ATRX, a guardian of chromatin. Trends Genet. 2023, 39, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, J.-P. Aging and epigenetic drift: A vicious cycle. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulen, M.F.; Samson, N.; Keller, A.; Schwabenland, M.; Liu, C.; Glück, S.; Thacker, V.V.; Favre, L.; Mangeat, B.; Kroese, L.J.; et al. cGAS–STING drives ageing-related inflammation and neurodegeneration. Nature 2023, 620, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouikli, A.; Tessarz, P. Epigenetic alterations in stem cell ageing—A promising target for age-reversing interventions? Brief. Funct. Genomics 2022, 21, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zant, G.; Liang, Y. The role of stem cells in aging. Exp. Hematol. 2003, 31, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrens, A.; Van Deursen, J.M.; Rudolph, K.L.; Schumacher, B. Impact of genomic damage and ageing on stem cell function. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xie, T. Stem Cell Niche: Structure and Function. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005, 21, 605–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrzewski, W.; Dobrzyński, M.; Szymonowicz, M.; Rybak, Z. Stem cells: Past, present, and future. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ermolaeva, M.; Neri, F.; Ori, A.; Rudolph, K.L. Cellular and epigenetic drivers of stem cell ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.K.; Blanpain, C.; Rossi, D.J. DNA damage response in adult stem cells: Pathways and consequences. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannino, G.; Russo, C.; Maugeri, G.; Musumeci, G.; Vicario, N.; Tibullo, D.; Giuffrida, R.; Parenti, R.; Lo Furno, D. Adult stem cell niches for tissue homeostasis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2022, 237, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, S. The effects of proliferation and DNA damage on hematopoietic stem cell function determine aging. Dev. Dyn. 2016, 245, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Vivona, E.; Kurre, P. Why hematopoietic stem cells fail in Fanconi anemia: Mechanisms and models. BioEssays 2025, 47, 2400191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Jakubison, B.; Keller, J.R. Protection of hematopoietic stem cells from stress-induced exhaustion and aging. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2020, 27, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, G.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. The role of DNA damage in neural stem cells ageing. J. Cell. Physiol. 2024, 239, e31187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, H.; Kusumoto, D.; Hashimoto, H.; Yuasa, S. Stem Cell Aging in Skeletal Muscle Regeneration and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Prat, L.; Sousa-Victor, P.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. Functional dysregulation of stem cells during aging: A focus on skeletal muscle stem cells. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 4051–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, P.; El-Jawhari, J.J.; Giannoudis, P.V.; Burska, A.N.; Ponchel, F.; Jones, E.A. Age-related Changes in Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Potential Impact on Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis Development. Cell Transplant. 2017, 26, 1520–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trani, J.P.; Chevalier, R.; Caron, L.; El Yazidi, C.; Broucqsault, N.; Toury, L.; Thomas, M.; Annab, K.; Binetruy, B.; De Sandre-Giovannoli, A.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from patients with premature aging syndromes display hallmarks of physiological aging. Life Sci. Alliance 2022, 5, e202201501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Deng, C.; Geng, S.; Weng, J.; Lai, P.; Liao, P.; Zeng, L.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Du, X. Premature exhaustion of mesenchymal stromal cells from myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 3462–3468. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, M.M.; Bickenbach, J.R. Epidermal stem cells are resistant to cellular aging. Aging Cell 2007, 6, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panich, U.; Sittithumcharee, G.; Rathviboon, N.; Jirawatnotai, S. Ultraviolet Radiation-Induced Skin Aging: The Role of DNA Damage and Oxidative Stress in Epidermal Stem Cell Damage Mediated Skin Aging. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 7370642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, H.; Wang, Y.-N.; Ding, Y.; Lin, Y.-Q.; Qin, J.; Wang, J.-C. Stem cell-based therapeutic strategies for liver aging. Liver Res. 2025, 9, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, G.G.; Dommann, N.; Karamichali, A.; Dionellis, V.S.; Asensio Aldave, A.; Yarahmadov, T.; Rodriguez-Carballo, E.; Keogh, A.; Candinas, D.; Stroka, D.; et al. In vivo DNA replication dynamics unveil aging-dependent replication stress. Cell 2024, 187, 6220–6234.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.N.; Ding, W.-X. The impact of aging on liver health and the development of liver diseases. Hepatol. Commun. 2025, 9, e0808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashizume, H.; Sato, K.; Takagi, H.; Kanda, D.; Kashihara, T.; Kiso, S.; Mori, M. Werner syndrome as a possible cause of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 62, 1043–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, P.; Schroll, M.; Fenzl, F.; Lederer, E.-M.; Hartinger, R.; Arnold, R.; Cagla Togan, D.; Guo, R.; Liu, S.; Petry, A.; et al. Inflammation and Fibrosis in Progeria: Organ-Specific Responses in an HGPS Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, R.A.; Essawy, M.M.; Barkat, M.A.; Awaad, A.K.; Thabet, E.H.; Hamed, H.A.; Elkafrawy, H.; Khalil, N.A.; Sallam, A.; Kholief, M.A.; et al. Cardiac stem cells: Current knowledge and future prospects. World J. Stem Cells 2022, 14, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianflone, E.; Torella, M.; Chimenti, C.; De Angelis, A.; Beltrami, A.P.; Urbanek, K.; Rota, M.; Torella, D. Adult Cardiac Stem Cell Aging: A Reversible Stochastic Phenomenon? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 5813147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, N.; Sussman, M.A. Cardiac aging—Getting to the stem of the problem. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 83, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Hosoyama, T.; Kawamura, D.; Takeuchi, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Samura, M.; Ueno, K.; Nishimoto, A.; Kurazumi, H.; Suzuki, R.; et al. Influence of aging on the quantity and quality of human cardiac stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olive, M.; Harten, I.; Mitchell, R.; Beers, J.K.; Djabali, K.; Cao, K.; Erdos, M.R.; Blair, C.; Funke, B.; Smoot, L.; et al. Cardiovascular Pathology in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria: Correlation with the Vascular Pathology of Aging. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.; Driscoll, B. Regeneration of the Aging Lung: A Mini-Review. Gerontology 2017, 63, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenberger, C.; Mühlfeld, C. Mechanisms of lung aging. Cell Tissue Res. 2017, 367, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.J.; Bessler, M. The genetics of dyskeratosis congenita. Cancer Genet. 2011, 204, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Santiago, G.M.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, R.; Gonzalez-Del Rosario, M.; Sierra-Zorita, R.; D Garcia, C. Interstitial lung disease in a patient with premature aging: Suspected Werner syndrome. Int. J. Case Rep. Images 2022, 13, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, N. Adult intestinal stem cells: Critical drivers of epithelial homeostasis and regeneration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beumer, J.; Clevers, H. Cell fate specification and differentiation in the adult mammalian intestine. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentinmikko, N.; Katajisto, P. The role of stem cell niche in intestinal aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 191, 111330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Imakiire, A.; Miyagawa, N.; Kasahara, T. A Report of Two Cases of Werner’s Syndrome and Review of the Literature. J. Orthop. Surg. 2003, 11, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callea, M.; Martinelli, D.; Cammarata-Scalisi, F.; Grimaldi, C.; Jilani, H.; Grimaldi, P.; Willoughby, C.E.; Morabito, A. Multisystemic Manifestations in Rare Diseases: The Experience of Dyskeratosis Congenita. Genes 2022, 13, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, R.; Cantley, L.G. The impact of aging on kidney repair. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2008, 294, F1265–F1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentijn, F.A.; Falke, L.L.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Goldschmeding, R. Cellular senescence in the aging and diseased kidney. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 12, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäkelä, J.-A.; Hobbs, R.M. Molecular regulation of spermatogonial stem cell renewal and differentiation. Reproduction 2019, 158, R169–R187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, R.; Krizhanovsky, V.; Baker, D.; d’Adda Di Fagagna, F. Cellular senescence in ageing: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Chen, S.; Yi, Z.; Zhao, R.; Zhu, J.; Ding, S.; Wu, J. The role of p21 in cellular senescence and aging-related diseases. Mol. Cells 2024, 47, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Pratico, D.; Bahijri, S.; Eldakhakhny, B.; Tuomilehto, J.; Wu, F.; Ren, J. Hallmarks and mechanisms of cellular senescence in aging and disease. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcinotto, A.; Kohli, J.; Zagato, E.; Pellegrini, L.; Demaria, M.; Alimonti, A. Cellular Senescence: Aging, Cancer, and Injury. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1047–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, S.; Alqahtani, T.; Venkatesan, K.; Sivadasan, D.; Ahmed, R.; Sirag, N.; Elfadil, H.; Abdullah Mohamed, H.; T.A., H.; Elsayed Ahmed, R.; et al. SASP Modulation for Cellular Rejuvenation and Tissue Homeostasis: Therapeutic Strategies and Molecular Insights. Cells 2025, 14, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Han, J.; Elisseeff, J.H.; Demaria, M. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its physiological and pathological implications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.-K. Antiaging agents: Safe interventions to slow aging and healthy life span extension. Nat. Prod. Bioprospecting 2022, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskalev, A.; Guvatova, Z.; Lopes, I.D.A.; Beckett, C.W.; Kennedy, B.K.; De Magalhaes, J.P.; Makarov, A.A. Targeting aging mechanisms: Pharmacological perspectives. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 33, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperka, T.; Wang, J.; Rudolph, K.L. DNA damage checkpoints in stem cells, ageing and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minchom, A.; Aversa, C.; Lopez, J. Dancing with the DNA damage response: Next-generation anti-cancer therapeutic strategies. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2018, 10, 1758835918786658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpay, F. Boosting NAD+ for Anti-Aging: Mechanisms, Interventions, and Opportunities. ChemRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.A.; Dominy, J.E.; Lee, Y.; Puigserver, P. The sirtuin family’s role in aging and age-associated pathologies. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, H.; Hu, Q.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ren, J.; Zhu, F.; Liu, G.-H. Epigenetic regulation of aging: Implications for interventions of aging and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.M.; Baker, D.J.; Van Deursen, J.M. Senescent Cells: A Novel Therapeutic Target for Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 93, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Farr, J.N.; Weigand, B.M.; Palmer, A.K.; Weivoda, M.M.; Inman, C.L.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Hachfeld, C.M.; Fraser, D.G.; et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Prahalad, V.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: Senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS J. 2023, 290, 1362–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Zhu, Y.; McGowan, S.J.; Angelini, L.; Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, H.; Xu, M.; Ling, Y.Y.; Melos, K.I.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Inman, C.L.; et al. Fisetin is a senotherapeutic that extends health and lifespan. EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliev, T.; Singh, P.B. Targeting Senescence: A Review of Senolytics and Senomorphics in Anti-Aging Interventions. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvarani, R.; Mohammed, S.; Richardson, A. Effect of rapamycin on aging and age-related diseases—Past and future. GeroScience 2021, 43, 1135–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gan, D.; Lin, S.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, M.; Zou, X.; Shao, Z.; Xiao, G. Metformin in aging and aging-related diseases: Clinical applications and relevant mechanisms. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2722–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griveau, A.; Wiel, C.; Ziegler, D.V.; Bergo, M.O.; Bernard, D. The JAK1/2 inhibitor ruxolitinib delays premature aging phenotypes. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.; Sousa-Victor, P.; Jasper, H. Rejuvenating Strategies for Stem Cell-Based Therapies in Aging. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 20, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browder, K.C.; Reddy, P.; Yamamoto, M.; Haghani, A.; Guillen, I.G.; Sahu, S.; Wang, C.; Luque, Y.; Prieto, J.; Shi, L.; et al. In vivo partial reprogramming alters age-associated molecular changes during physiological aging in mice. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varesi, A.; Chirumbolo, S.; Campagnoli, L.I.M.; Pierella, E.; Piccini, G.B.; Carrara, A.; Ricevuti, G.; Scassellati, C.; Bonvicini, C.; Pascale, A. The Role of Antioxidants in the Interplay between Oxidative Stress and Senescence. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagbohun, O.F.; Gillies, C.R.; Murphy, K.P.J.; Rupasinghe, H.P.V. Role of Antioxidant Vitamins and Other Micronutrients on Regulations of Specific Genes and Signaling Pathways in the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lv, X.; Xu, W.; Li, X.; Tang, X.; Huang, H.; Yang, M.; Ma, S.; Wang, N.; Niu, Y. Effects of the periodic fasting-mimicking diet on health, lifespan, and multiple diseases: A narrative review and clinical implications. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, e412–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.; Ebissy, E.; Mohamed, R.; Ateya, A. Effects of antioxidant vitamins (A, D, E) and trace elements (Cu, Mn, Se, Zn) administration on gene expression, metabolic, antioxidants and immunological profiles during transition period in dromedary camels. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, P.; Huang, H. Inflammation and aging: Signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medoro, A.; Saso, L.; Scapagnini, G.; Davinelli, S. NRF2 signaling pathway and telomere length in aging and age-related diseases. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2024, 479, 2597–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.; Deelen, J.; Illario, M.; Adams, J. Challenges in anti-aging medicine–trends in biomarker discovery and therapeutic interventions for a healthy lifespan. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 2643–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiserman, A.M.; Lushchak, O.V.; Koliada, A.K. Anti-aging pharmacology: Promises and pitfalls. Ageing Res. Rev. 2016, 31, 9–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Syndrome | Gene/Protein | Frequent Mutations | Molecular Functions | Aging Phenotypes/Senescence Link | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

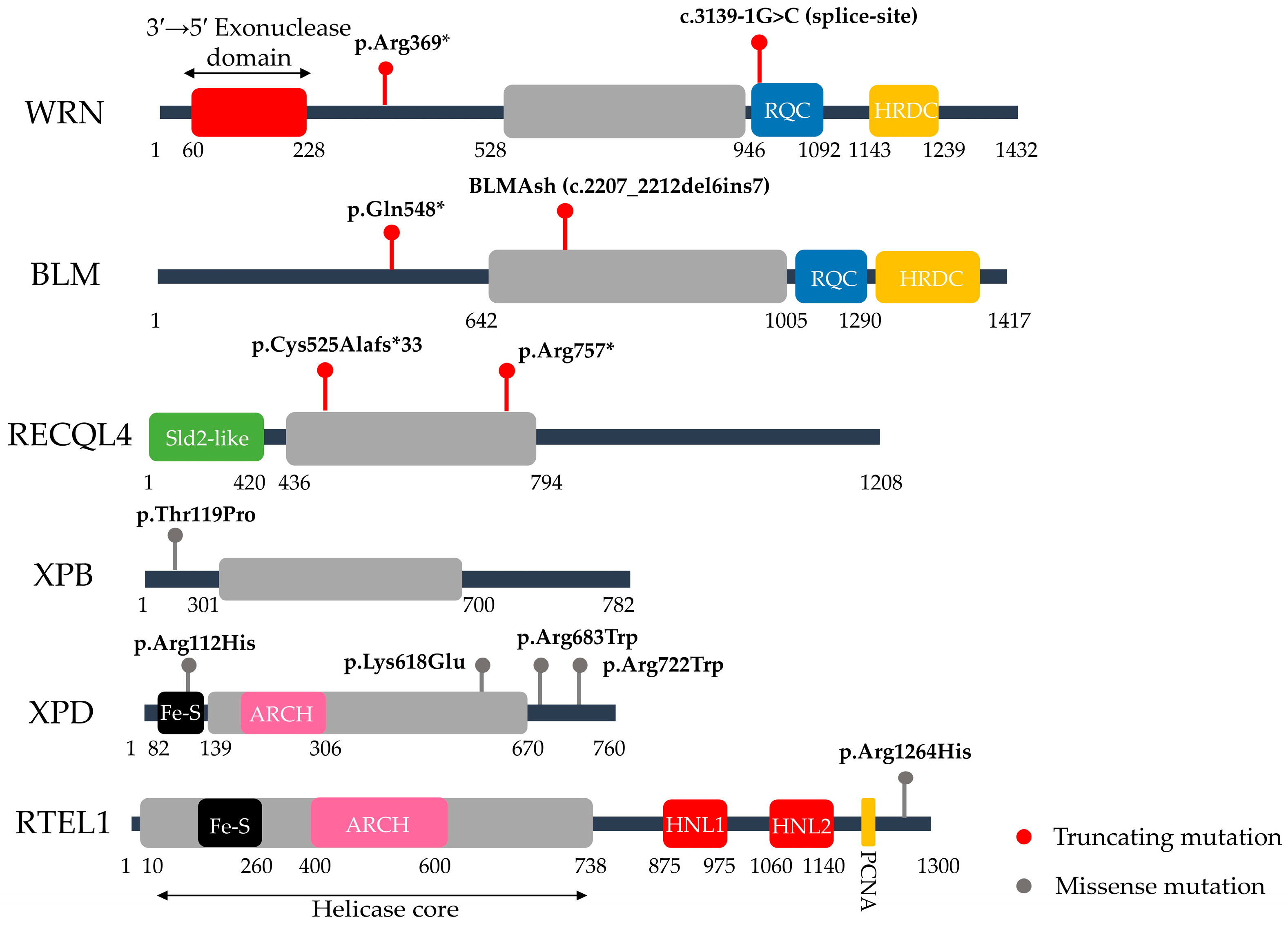

| Defects in Helicase Function | Werner Syndrome (WS) | WRN (RecQ Helicase & Exonuclease) | c.1105C>T (p.Arg369*, nonsense, exon 9) & c.3139-1G>C (splice-site, exon 26) >70 WRN variants | Resolves complex DNA structures (e.g., G-quadruplexes); telomere maintenance; DSB repair regulation (c-NHEJ vs. alt-NHEJ) | Hair graying, cataracts, osteoporosis, atherosclerosis, cancer; linked to telomere shortening and persistent DDR, drivers of senescence | [20,21,22,23,24] |

| Bloom Syndrome (BS) | BLM (RecQ Helicase) | c.2207_2212del6ins7 (BLMAsh, exon 10) & c.1642C>T (p.Gln548*, nonsense, exon 7), >150 BLM variants | Suppresses aberrant homologous recombination; dissolves double Holliday junctions via the BTR complex; ensures replication fork stability and genome maintenance under replication stress | Does not present classical premature aging traits, but is characterized by short stature, proportional growth deficiency, immunodeficiency, sun-sensitive skin changes, and very high cancer predisposition. | [20,25,26,27,28,29] | |

| Rothmund Thomson Syndrome (RTS) | RECQL4 (RecQ Helicase) | c.1573delT (p.Cys525Alafs*33, frameshift, exon 9) & c.2269C>T (p.Arg757*, nonsense, exon 14), >100 RECQL4 variants | DNA replication; DNA repair (DSB repair, HR, NHEJ); Mitochondrial DNA integrity | Poikiloderma, skeletal abnormalities, juvenile cataracts & cancer predisposition. RECQL4 deficiency leads to DNA damage accumulation, with cellular senescence observed in vitro, although cancer predisposition is the dominant clinical outcome. | [30,31,32,33,34] | |

| Dyskeratosis Congenita (DC) | RTEL1 (DNA helicase) | c.3791G>A (p.Arg1264His, exon 34), >70 RTEL1 variants | Telomerase biogenesis; telomere replication and protection. | Abnormal skin pigmentation, nail dystrophy, leucoplakia, bone marrow failure, pulmonary fibrosis & liver disease. Critically short telomeres cause premature stem cell senescence, leading to progressive tissue failure. | [35,36,37] | |

| TERC (RNA component) | n.64C>G (structural RNA variant) & n.110A>G (structural RNA variant), >30 TERC variants | |||||

| TERT (reverse transcriptase) | c.2594G>A (p.Arg865His, exon 11), >100 TERT variants | |||||

| DKC1 (RNA pseudouridine synthase) | c.1058C>T (p.Ala353Val, exon 12) >60 DKC1 variants | |||||

| TINF2 (shelterin protein) | c.844C>T (p.Arg282His, exon 6), >40 TINF2 variants | |||||

| Trichothiodystrophy (TTD) | ERCC2/XPD (DNA helicase, TFIIH complex) | c.2164C>T (p.Arg722Trp, missense) & c.335G>A (p.Arg112His, exon 5, missense), >40 ERCC2 variants | TFIIH complex component; global genome NER; transcription-coupled NER; transcription initiation. | Brittle hair and nails, progressive sensorineural deafness, photosensitivity, intellectual disability and reduced fertility. Some forms lack cancer predisposition. Defects in both NER and transcription contribute to early cellular aging. | [38,39,40,41,42] | |

| ERCC3/XPB (DNA helicase, TFIIH complex) | c.355A>C (p.Thr119Pro, exon 3), <10 ERCC3 variants | |||||

| GTF2H5 (structural TFIIH subunit) | c.166C>T (p.Arg56Ter, exon 2) & c.2T>C (p.Met1Thr, start codon), <10 GTF2H5 variants | |||||

| Defects in Helicase & Nuclease Function | Xeroderma Pigmentosum (XP) | XPA (scaffold protein) | c.390-1G>C (splice-site, intron 3), >40 XPA variants | Global genome NER (bulky adduct/UV lesion removal); transcription-coupled NER (in some subtypes). | Extreme UV sensitivity with early-onset skin cancers; neurodegeneration occurs in some subtypes. Persistent unrepaired DNA damage leads to chronic DDR activation and premature cellular senescence | [43,44,45,46,47] |

| XPC (damage recognition) | c.1643_1644delTG (p.Val548Alafs*25, exon 9), >120 XPC variants | |||||

| ERCC2/XPD (DNA helicase, TFIIH complex) | c.1993A>G (p.Lys618Glu, exon 21) & c.2047C>T (p.Arg683Trp, exon 22), >100 ERCC2 variants | |||||

| ERCC3/XPB (DNA helicase, TFIIH complex) | Rare, <20 ERCC3 variants | |||||

| ERCC4/XPF (structure-specific endonuclease) | c.2395C>T (p.Arg799Trp, exon 8), <30 ERCC4 variants | |||||

| ERCC5/XPG (structure-specific endonuclease) | c.4G>T (p.Gly2Trp) & c.1947T>A (p.Tyr649*), <20 ERCC5 variants | |||||

| POLH (DNA polymerase eta) | c.907C>T (p.Arg304Trp, exon 8), >50 POLH variants | |||||

| Other DDR defects tegoryility. Some forms lackoutvery cancer | Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome (NBS) | NBN (scaffold protein in MRN complex) | c.657_661del5 (p.K219fsX19, exon 6), >11 NBN variants | MRN complex component; DSB sensing; telomere stability. | Microcephaly, immunodeficiency, cellular & humoral immunodeficiency, cancer predisposition. Genomic instability accelerates senescence, acting as a tumor-suppressive barrier. | [48,49,27] |

| Fanconi Anemia (FA) | FANCA | c.3788_3790delTCT (p.Phe1263del, exon 38), > 250 FANCA variants | DNA interstrand crosslink (ICL) repair; replication stress protection; chromosome stability. | Progressive bone marrow failure, developmental anomalies, skin pigmentation changes & cancer predisposition. Persistent DNA damage and replication stress induces senescence, driving hematopoietic stem cell exhaustion. | [50,51,52,53,54,55] | |

| FANCC | c.456+4A>T (splice-site, intron 4), >60 FANCC variants | |||||

| FANCG | c.307+1G>C (splice donor, intron 3), >50 FANCG variants | |||||

| FANCD1 (BRCA2) & >20 other FA genes | c.6174delT (p.Ser1982fs, exon 11), >100 FANCD1 | |||||

| Ataxia Telangiectasia (AT) | ATM (Ataxia–Telangiectasia Mutated kinase) | c.7630-2A>C (splice-site, intron 53) & c.8147T>C (p.Val2716Ala, exon 56), >1000 ATM variants | ATM–DSB signaling; checkpoint control; telomere maintenance; oxidative and mitochondrial homeostasis. | Progressive neurodegeneration, immunodeficiency, cancer predisposition & radiosensitivity. Persistent DDR activation with oxidative damage and mitochondrial dysfunction drives early senescence. | [27,56,57,58] | |

| Cockayne Syndrome (CS) | ERCC6/CSB (ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler) | c.5254_5257del (p.Thr1752fs*6, exon 23) & c.1834C>T (p.Arg612Ter, exon 9), >150 ERCC6 variants | Transcription-coupled NER (removal of RNA Pol II-blocking lesions); transcription regulation; chromatin remodeling. | Growth failure, neurodegeneration, sensorineural hearing loss, photosensitivity, cachectic dwarfism & no cancer predisposition. Persistent transcription-blocking lesions induce senescence. | [20,47,59,60,61,62] | |

| ERCC8/CSA (WD-repeat ubiquitin ligase component) & other ERCC genes | Complex exon 4 rearrangement (del/inv/ins, exon 4), >80 ERCC8 variants | |||||

| Defects in Nuclear Envelope | Hutchinson Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) | LMNA | c.1824C>T (p.G608G, ex11), >20 LMNA variants (90% of cases due to this founder mutation) | Nuclear lamina structure; chromatin organization; telomere maintenance. | Accelerated atherosclerosis, alopecia, lipodystrophy, joint stiffness, and severe premature aging driven by persistent DDR signaling from nuclear architecture defects. | [63,64,65] |

| Mandibuloacral Dysplasia (MAD) | LMNA | c.1580G>A (p.Arg527His, ex9), >20 LMNA variants | Lamin structure; nuclear architecture | Growth retardation, skeletal abnormalities, partial lipodystrophy, progeroid features. Nuclear envelope fragility induces chronic DDR and early senescence. | [66,67,68] | |

| ZMPSTE24 (zinc metalloprotease) | c.1085dupT (p.Phe361fs, ex9), >30 ZMPSTE24 variants | |||||

| POLD1 (catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase δ) | c.1812_1814del (p.Ser605del, exon 15), <10 POLD1 variants |

| Model Type | Mouse Model | Gene/Protein | Molecular Functions | Aging Phenotypes/Senescence Link | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defects in Helicase Function | Wrn−/− (null) WrnΔhel/Δhel(helicase-dead) | Wrn (RecQ helicase) | DNA replication, recombination & telomere maintenance | Null: mild or no overt aging, fertile, near-normal lifespan with only subtle senescence. WrnΔhel/Δhel: clear aging features, reduced lifespan, increased oxidative stress, metabolic abnormalities, and cancer predisposition. | [78,79,80,81] |

| Wrn−/− Terc−/− | Wrn (RecQ helicase) & Terc (telomerase RNA component) | DNA replication, recombination & telomere maintenance | Hair graying, osteoporosis, cataracts, diabetes, and cancer. Accelerated telomere erosion drives persistent DNA damage signaling and widespread senescence, closely mirroring the human Werner syndrome phenotype. | [23,82] | |

| Blm−/−(null) Blm3/3 (hypomorphic) BlmloxP/loxP (conditional) | Blm (RecQ helicase) | Homologous recombination, suppression of sister chromatin exchange (SCE), maintenance of replication fork stability | Nulls: perinatal lethality. Hypomorphic/conditional mutants: viable, genomic instability, elevated SCE, cancer predisposition, shortened lifespan, underscoring genome instability as the driver of aging phenotypes. | [83,84] | |

| Recql4−/− (null) Recql4hd/hd (hypo-morphic) Recql4loxP/loxP (conditional) | Recql4 (RecQ helicase) | DNA replication initiation, NER/NHEJ, mtDNA stability | Nulls: embryonically lethal. Hypomorphic/conditional mutants: viable, growth retardation, skeletal abnormalities, genomic instability, cancer predisposition, and early senescence. Recql4 deficiency models Rothmund–Thomson syndrome, linking replication defects and genome instability to accelerated aging. | [85,86] | |

| Defects in Nuclease function | Ercc1−/− (null), Ercc1−/Δ (hypomorphic) | Ercc1 (ERCC1–XPF endonuclease) | NER & interstrand crosslink (ICL) repair, supports transcription-coupled repair | Nulls: early lethality. Hypomorphs: systemic progeroid features, growth retardation, multi-organ decline & shortened lifespan. Accelerated epigenetic aging, high senescent cell burden, underscoring persistent DNA lesions and chronic DDR as drivers of senescence and tissue aging. | [74,87,88] |

| Defects in Helicase & Nuclease Function | Xpg−/− (null), XpdTTD/TTD (hypomorphic) | Ercc5/Xpg (structure-specific endonuclease) Ercc2/Xpd (DNA helicase) | Both impair NER lesion excision, TFIIH-mediated transcription initiation | Cachexia, brittle hair, neurodegeneration, retinal degeneration, growth retardation, and shortened lifespan. Mimics human trichothiodystrophy. Persistent NER defects and transcription-blocking lesions drive chronic DDR and senescence. | [89,90] |

| Other DDR defects | Atm−/− (null) | Atm (ATM kinase) | DSB signaling, checkpoint control, oxidative stress response | Growth retardation, infertility, immunodeficiency, neurodegeneration, increased tumor incidence, reduced lifespan. Persistent DSB signaling drives senescence and stem cell exhaustion, contributing to premature aging. | [91,92,93] |

| Csa−/−, Csb−/− | Ercc8/Csa (WD40-repeat protein) Ercc6/Csb (ATP-dependent chromatin remodeler) | Transcription-coupled NER, transcription regulation, mitochondrial function | Growth retardation, cachexia, neurological dysfunction, kyphosis, retinal degeneration, and reduced fertility. Lifespan is shortened without marked cancer predisposition. Persistent transcription-blocking lesions drive senescence. | [94,95] | |

| Prkdc−/− (SCID mouse) | Prkdc (DNA-PKcs kinases) | NHEJ, V(D)J recombination, DSB repair & telomere stability | Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), growth retardation, osteoporosis, kyphosis, shortened lifespan. Progressive stem cell exhaustion from persistent DSBs and telomere dysfunction drives chronic DDR, p53/p21-mediated senescence, and accelerated aging. | [93,96] | |

| Ku80−/− | Xrcc5/Ku80 (DNA end-binding protein) | NHEJ, V(D)J recombination, DSB repair & telomere stability | Growth retardation, shortened lifespan, early osteoporosis, kyphosis, stem cell exhaustion, and impaired immune development. Persistent DSBs sustain DDR activation and p53-driven senescence, accelerating systemic aging | [97,98] | |

| Fanca−/−, Fancc−/−, Fancg−/− (nulls) | Fanca, Fancc, Fancg (FA core complex subunits) | ICL repair, replication fork protection, telomere stability | Mice are viable and do not exhibit systemic progeroid features, but show hematopoietic stem cell attrition, progressive bone marrow failure, and heightened genotoxic sensitivity. Replication stress and unrepaired DNA damage in stem cells trigger p53/p21-mediated senescence, resulting in segmental rather than systemic aging. | [99,100] | |

| Defects in Nuclear Envelope (Laminopathies) | HGPS knock-in models (LmnaHG & LmnaG609G) | Lmna (Progerin/ mutant Lamin A) | Nuclear envelope stability, chromatin organization, DDR signaling | Growth retardation, bone and cardiovascular abnormalities, reduced lifespan. Progerin accumulation disrupts nuclear architecture, induces persistent DDR activation, and promotes cellular senescence resembling human HGPS. | [75,101,102] |

| Zmpste24−/− | Zmpste24 (metalloprotease) | Nuclear envelope integrity (maturation of prelamin A to lamin A) | Severe progeroid phenotype with growth retardation, osteoporosis, kyphosis, muscle weakness, early death. Prelamin A accumulation disrupts nuclear architecture, induces DNA damage and senescence. | [75,103,104] | |

| Lmna−/− | Lmna (Lamnin A & C) | Nuclear envelope structure, chromatin organization, DDR signaling | Severe muscular dystrophy, growth retardation, and early death. Phenotype reflects developmental failure rather than systemic progeria and thus differs from HGPS knock-in and Zmpste24−/− models that recapitulate premature aging. | [75] | |

| Defects in Mitochondrial Function | Polgmut/mut (D257A knock-in) | Polg (DNA polymerase γ) | mtDNA replication & proofreading | Alopecia, kyphosis, osteoporosis, anemia, cardiomyopathy, infertility, and shortened lifespan. Mitochondrial dysfunction induces ROS imbalance and triggers persistent DDR signaling, driving cellular senescence and stem cell exhaustion. | [105,106] |

| Senescence Accelerated Models | SAMP strains | Polygenic variants, derived by selective inbreeding of AKR/J mice. | Mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS regulation & tissue homeostasis | Shortened lifespan with strain-specific pathologies: SAMP1 (amyloidosis), SAMP6 (osteoporosis), SAMP8 (neurodegeneration & amyloid-β and tau pathology). ROS-driven mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular senescence promote chronic inflammation and systemic aging. | [76,107] |

| Induced Accelerated Aging Models | D-galactose-treated mouse | Excess galactose metabolism (chemical induction) | ROS overproduction, AGE–RAGE signaling, mitochondrial dysfunction & DDR activation | Systemic aging phenotypes in brain, heart, liver, kidney, reproductive system. Strong DDR activation and apoptosis in multiple tissues. | [108,109] |

| Total Body Irradiation (TBI) | DSBs (ionizing radiation) | Ionizing radiation-induced DSBs and ROS leading to DDR activation | Hematopoietic stem cell senescence with long-term marrow impairment, intestinal senescence with dysbiosis and absorption defects, hair whitening. Persistent DDR signaling accelerates senescence. | [110,111] |

| Category | Mechanism/Target | Representative Agents | Principal Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct DDR checkpoint and repair modulation | Checkpoint inhibition (p21, PUMA, EXO1, p16INK4a), ATM/ATR inhibition | Experimental checkpoint gene suppression; ATM/ATR inhibitors (oncology) | Extends lifespan/tissue maintenance in telomere-deficient mice; ATR restores origin firing in aged liver but induces inflammation without proliferative rejuvenation; human efficacy unproven. |

| NAD+ restoration (supports PARPs, sirtuins, DNA repair) | NR, NMN | Enhanced DNA repair, mitochondrial function, stress resistance | |

| Sirtuin activation | Resveratrol, SRT1720, SRT2104 | Improved metabolic & inflammatory markers; lifespan extension inconsistent | |

| Epigenetic modulation (HDAC/DNMT/BET) | Vorinostat, panobinostat; azacitidine, decitabine; JQ1 | Restoration of repair fidelity, epigenome remodeling; toxicity limits use. | |

| Downstream targeting of DDR-induced senescence | Senolytics (eliminate senescent cells) | Dasatinib + quercetin, navitoclax, fisetin | Reduced senescent cell burden, alleviated dysfunction, lifespan extension in mice |

| Senomorphics (suppress SASP, modulate phenotype) | Rapamycin, metformin, ruxolitinib, NF-κB and p38 inhibitors | SASP suppression, reduced inflammation, tissue homeostasis, lifespan extension in models | |

| Stem cell–based regenerative therapies | MSC/HSC transplantation; partial reprogramming | Restored regenerative capacity, rejuvenation of aged tissues in preclinical models | |

| Indirect reduction of DNA damage & stress | Antioxidants, ROS modulators | N-acetylcysteine (NAC), MitoQ, CoQ10, SkQ1 | Reduced oxidative stress, DNA damage, delayed senescence |

| Dietary antioxidants (Micronutrients) | Vitamins A, C, D, E, K, B-complex; selenium; zinc | Reduction of oxidative DNA damage; maintenance of genomic stability | |

| Nutritional/metabolic interventions | Caloric restriction, fasting-mimicking diets | Lower ROS production, enhanced genome maintenance, lifespan extension | |

| Polyphenol-rich nutritional interventions | Resveratrol, quercetin, curcumin (Mediterranean diet pattern) | Enhanced DNA repair and reinforced cellular stress resilience | |

| Anti-inflammatory strategies | Anakinra (IL-1), tocilizumab (IL-6) | Improved hematopoietic regeneration, tissue homeostasis | |

| NRF2 activation | Sulforaphane, dimethyl fumarate, bardoxolone | Enhanced stress resilience, genome stability, delayed senescence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Margariti, A.; Daniil, P.; Rampias, T. The Converging Roles of Nucleases and Helicases in Genome Maintenance and the Aging Process. Life 2025, 15, 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111729

Margariti A, Daniil P, Rampias T. The Converging Roles of Nucleases and Helicases in Genome Maintenance and the Aging Process. Life. 2025; 15(11):1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111729

Chicago/Turabian StyleMargariti, Aikaterini, Persefoni Daniil, and Theodoros Rampias. 2025. "The Converging Roles of Nucleases and Helicases in Genome Maintenance and the Aging Process" Life 15, no. 11: 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111729

APA StyleMargariti, A., Daniil, P., & Rampias, T. (2025). The Converging Roles of Nucleases and Helicases in Genome Maintenance and the Aging Process. Life, 15(11), 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15111729