Analysis of Clinically Symptomatic Patients to Differentiate Inflammatory Breast Cancer from Mastitis in Asian Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Clinical and Demographic Data

2.3. Ultrasound Examination and Analysis

2.4. Histopathology Review

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

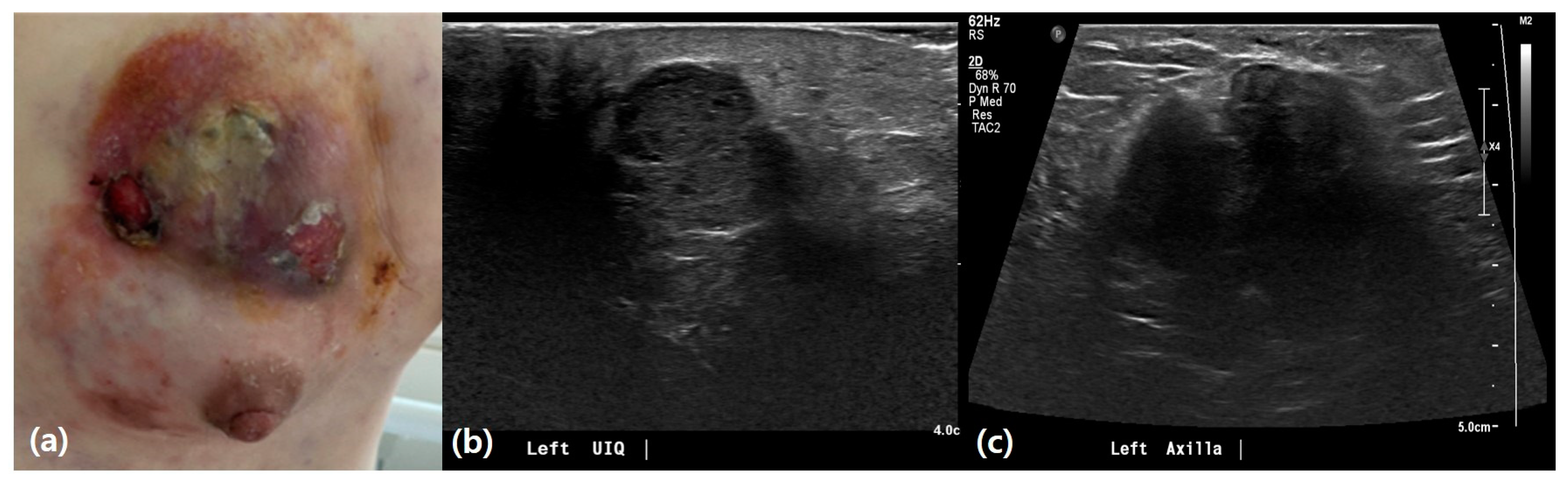

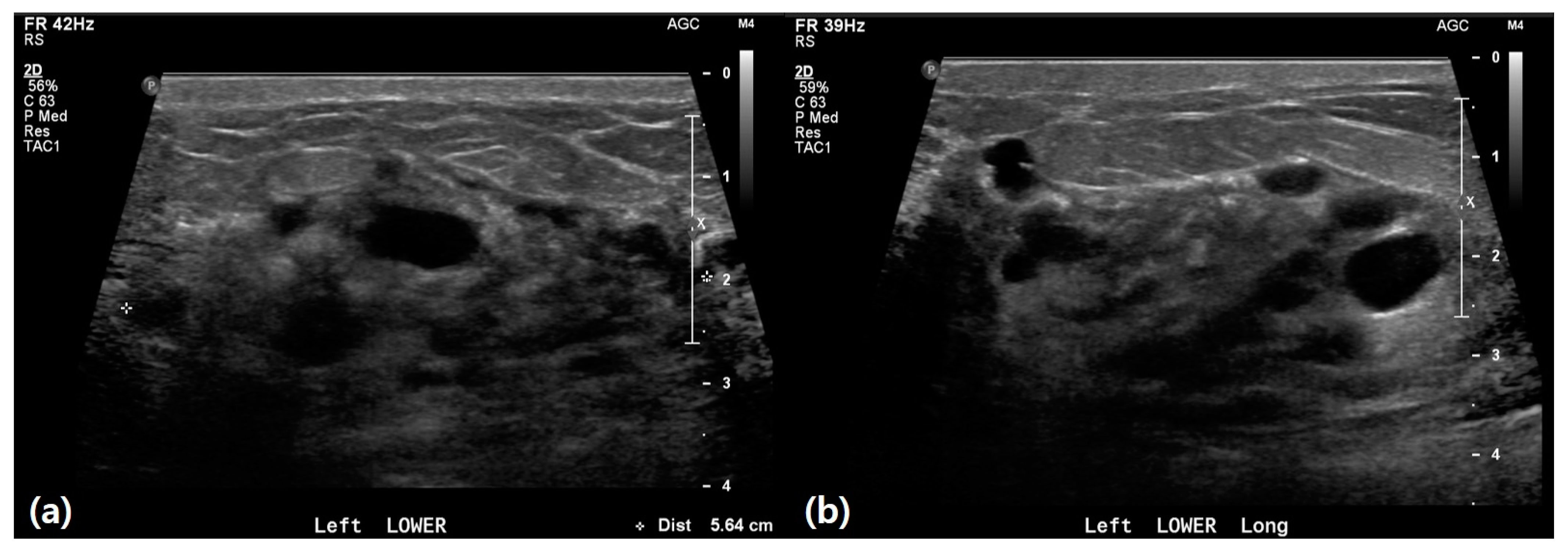

3.2. Ultrasound Features

3.3. Pathological and Biopsy Results

3.4. Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Associated with IBC

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Froman, J.; Landercasper, J.; Ellis, R.; De Maiffe, B.; Theede, L. Red breast as a presenting complaint at a breast center: An institutional review. Surgery 2011, 149, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferron, S.; Asad-Syed, M.; Boisserie-Lacroix, M.; Palussière, J.; Hurtevent, G. Imaging benign inflammatory syndromes. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2012, 93, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boisserie-Lacroix, M.; Debled, M.; Tunon de Lara, C.; Hurtevent, G.; Asad-Syed, M.; Ferron, S. The inflammatory breast: Management, decision-making algorithms, therapeutic principles. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2012, 93, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutet, G. Breast inflammation: Clinical examination, aetiological pointers. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2012, 93, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, S.; Cristofanilli, M. Inflammatory breast cancer: What progress have we made? Oncology 2011, 25, 264–270, 273. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.J.; Tannenbaum, N.E. Inflammatory carcinoma of the breast. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1924, 39, 580–595. [Google Scholar]

- Menta, A.; Fouad, T.M.; Lucci, A.; Le-Petross, H.; Stauder, M.C.; Woodward, W.A.; Ueno, N.T.; Lim, B. Inflammatory Breast Cancer: What to Know About This Unique, Aggressive Breast Cancer. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 98, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Petross, H.T.; Balema, W.; Woodward, W.A. Why diagnosing inflammatory breast cancer is hard and how to overcome the challenges: A narrative review. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabi, Y.; Darrigues, L.; Pons, K.; Mabille, M.; Abd Alsamad, I.; Mitri, R.; Skalli, D.; Haddad, B.; Touboul, C. Incidence of inflammatory breast cancer in patients with clinical inflammatory breast symptoms. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, R.M.; Hamed, S.T.; Salem, D.S. Classification of inflammatory breast disorders and step by step diagnosis. Breast J. 2009, 15, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, S.; Tadros, A.B. New Strategies for Locally Advanced Breast Cancer: A Review of Inflammatory Breast Cancer and Nonresponders. Clin. Breast Cancer 2024, 24, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hester, R.H.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Lim, B. Inflammatory breast cancer: Early recognition and diagnosis is critical. Am. J. Obs. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, F.M.; Bondy, M.; Yang, W.; Yamauchi, H.; Wiggins, S.; Kamrudin, S.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Le-Petross, H.; Bidaut, L.; Player, A.N.; et al. Inflammatory breast cancer: The disease, the biology, the treatment. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2010, 60, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagsi, R.; Mason, G.; Overmoyer, B.A.; Woodward, W.A.; Badve, S.; Schneider, R.J.; Lang, J.E.; Alpaugh, M.; Williams, K.P.; Vaught, D.; et al. Inflammatory breast cancer defined: Proposed common diagnostic criteria to guide treatment and research. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 192, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, S.P.; Shen, Z.Z.; Liu, T.J.; Agarwal, G.; Tajima, T.; Paik, N.S.; Sandelin, K.; Derossis, A.; Cody, H.; Foulkes, W.D. Is breast cancer the same disease in Asian and Western countries? World J. Surg. 2010, 34, 2308–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, M.; Raina, V. Epidemiology, screening and diagnosis of breast cancer in the Asia–Pacific region: Current perspectives and important considerations. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 4, S5–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, C.B.; Jan, A. BMI Classification Percentile and Cut Off Points. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lê, M.G.; Arriagada, R.; Contesso, G.; Cammoun, M.; Pfeiffer, F.; Tabbane, F.; Bahi, J.; Dilaj, M.; Spielmann, M.; Travagli, J.P.; et al. Dermal lymphatic emboli in inflammatory and noninflammatory breast cancer: A French-Tunisian joint study in 337 patients. Clin. Breast Cancer 2005, 6, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.C.; Grimm, M.; Sukumar, J.; Schnell, P.M.; Park, K.U.; Stover, D.G.; Jhawar, S.R.; Gatti-Mays, M.; Wesolowski, R.; Williams, N.; et al. Survival outcomes seen with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the management of locally advanced inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) versus matched controls. Breast 2023, 72, 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, E.; Gardin, G.; Evagelista, G.; Prochilo, T.; Collecchi, P.; Lionetto, R. Long-term results of combined-modality therapy for inflammatory breast carcinoma. Clin. Breast Cancer 2004, 5, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, N.T.; Fernandez, J.R.E.; Cristofanilli, M.; Overmoyer, B.; Rea, D.; Berdichevski, F.; El-Shinawi, M.; Bellon, J.; Le-Petross, H.T.; Lucci, A.; et al. International Consensus on the Clinical Management of Inflammatory Breast Cancer from the Morgan Welch Inflammatory Breast Cancer Research Program 10th Anniversary Conference. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, H.G.; Xia, Y.; Mukherjee, B.; Merajver, S.D. Incidence and survival of inflammatory breast cancer between 1973 and 2015 in the SEER database. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 185, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glechner, A.; Wagner, G.; Mitus, J.W.; Teufer, B.; Klerings, I.; Böck, N.; Grillich, L.; Berzaczy, D.; Helbich, T.H.; Gartlehner, G. Mammography in combination with breast ultrasonography versus mammography for breast cancer screening in women at average risk. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 3, CD009632. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, G.; Findeklee, S.; del Sol Martinez, G.; Georgescu, M.T.; Gerlinger, C.; Nemat, S.; Klamminger, G.G.; Nigdelis, M.P.; Solomayer, E.F.; Hamoud, B.H. Accuracy of Breast Ultrasonography and Mammography in Comparison with Postoperative Histopathology in Breast Cancer Patients after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lequin, M.H.; van Spengler, J.; van Pel, R.; van Eijck, C.; van Overhagen, H. Mammographic and sonographic spectrum of non-puerperal mastitis. Eur. J. Radiol. 1995, 21, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lee, K.W.; Chung, S.Y.; Yang, I.; Kim, H.D.; Shin, S.J.; Kim, J.E.; Chung, B.W.; Choi, J.A. Inflammatory breast cancer: Imaging findings. Clin. Imaging 2005, 29, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uematsu, T. MRI findings of inflammatory breast cancer, locally advanced breast cancer, and acute mastitis: T2-weighted images can increase the specificity of inflammatory breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2012, 19, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghav, K.; French, J.T.; Ueno, N.T.; Lei, X.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Reuben, J.M.; Valero, V.; Ibrahim, N.K. Inflammatory Breast Cancer: A Distinct Clinicopathological Entity Transcending Histological Distinction. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günhan-Bilgen, I.; Üstün, E.E.; Memiş, A. Inflammatory Breast Carcinoma: Mammographic, Ultrasonographic, Clinical, and Pathologic Findings in 142 Cases. Radiology 2002, 223, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Total | IBC | Mastitis | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Patients | 101 | n = 14 (13.9%) | n = 87 (86.1%) | |

| Age | ||||

| (mean ± SD) | 39.5 ± 12.1 | 46.4 ± 11.4 | 38.4 ± 11.9 | 0.020 |

| (median, IQR) | 37.0 (32.0–44.0) | 44.5 (39.8–58.3) | 35.0 (32.0–4.0) | |

| ≥40 years | 34 (33.7%) | 11 (78.6%) | 23 (26.4%) | <0.001 |

| <40 years | 67 (66.3%) | 3 (21.4%) | 64 (73.6%) | |

| BMI | ||||

| (mean ± SD) | 25.1 ± 4.5 | 28.8 ± 3.9 | 24.4 ± 4.3 | 0.009 |

| Underweight: BMI < 18.5 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.043 |

| Normal weight: BMI 18.5–22.9 | 20 (39.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 20 (46.5%) | |

| Overweight: BMI 23–24.9 | 5(9.8%) | 1(12.5%) | 4 (9.3%) | |

| Obesity: BMI ≥ 25 | 26 (51.0%) | 7(87.5%) | 19 (44.2%) | |

| Normal weight | 20 (39.2%) | 0(0.0%) | 20 (46.5%) | 0.012 |

| Overweight + Obesity | 31 (60.8%) | 8 (100.0%) | 23 (53.5%) | |

| Menopausal Status | ||||

| Premenopause | 82 (81.2%) | 6 (42.9%) | 76 (87.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Postmenopause | 19 (18.8%) | 8 (57.1%) | 11 (12.6%) | |

| During Pregnancy/Lactation | ||||

| Yes | 23 (22.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | 21 (24.1%) | 0.333 |

| No | 78 (77.2%) | 12 (85.7%) | 66 (75.9%) | |

| Symptom Onset (days ago) | ||||

| (mean ± SD) | 16.7 ± 17.0 | 37.7 ± 21.3 | 12.7 ± 12.8 | 0.002 |

| (median, IQR) | 14.0 (7.0–30.0) | 60.0 (18.8–60.0) | 10.0 (5.0–20.0) | |

| Localized Symptoms | ||||

| Erythema | 38 (37.6%) | 5 (35.7%) | 33 (37.9%) | 0.562 |

| Swelling | 19 (18.8%) | 7 (50.0%) | 12 (13.8%) | 0.004 |

| Skin change | 26 (25.7%) | 3 (21.4%) | 23 (26.4%) | 0.489 |

| Warmth | 24 (23.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | 22 (25.3%) | 0.300 |

| Mass | 48 (47.5%) | 7 (50.0%) | 41 (47.1%) | 0.534 |

| Pain/discomfort | 48 (47.5%) | 6 (42.9%) | 42 (48.3%) | 0.466 |

| Number of Localized Symptoms | ||||

| (mean ± SD) | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 0.515 |

| (median, IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.8–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | |

| Systemic Symptoms | ||||

| Yes | 7 (6.9%) | 1 (7.1%) | 6 (6.9%) | 0.660 |

| No | 94 (93.1%) | 13 (92.9%) | 81 (93.1%) | |

| Previous Mastitis History | ||||

| Yes | 34 (33.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 33 (37.9%) | 0.019 |

| No | 67 (66.3%) | 13 (92.9%) | 54 (62.1%) | |

| Personal History of Cancer | ||||

| Yes | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.861 |

| No | 100 (99.0%) | 14 (100.0%) | 86 (98.9%) | |

| Family History of Breast Cancer | ||||

| Yes | 3 (3.0%) | 0(0.0%) | 3 (3.4%) | 0.636 |

| No | 98 (97.0%) | 14 (100.0%) | 84 (96.6%) | |

| Underlying Diseases | ||||

| DM/metabolic syndrome | 18 (17.8%) | 2 (14.3%) | 16 (18.4%) | 0.646 |

| Immunocompromised | 4 (4.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (4.6%) | |

| No | 79 (78.2%) | 12 (85.7%) | 67 (77.0%) | |

| Mental disorder | ||||

| Yes | 8 (7.9%) | 1 (7.1%) | 7 (8.0%) | 0.694 |

| No | 93 (92.1%) | 13 (92.9%) | 80 (92.0%) | |

| Drinking | ||||

| Yes | 10 (13.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 10 (16.1%) | 0.113 |

| No | 66 (86.6%) | 14 (100.0%) | 52 (83.9%) | |

| Smoking | ||||

| Yes | 4 (5.3%) | 0(0.0%) | 4 (6.5%) | 0.435 |

| No | 72 (94.7%) | 14 (100.0%) | 58 (93.5%) |

| Variables | Total | IBC | Mastitis | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilaterality | ||||

| Right | 50 (49.5%) | 8 (57.1%) | 42 (48.3%) | 0.780 |

| Left | 50 (49.5%) | 6 (42.9%) | 44 (50.6%) | |

| Both | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Lesion Type | ||||

| Mass | 31 (30.7%) | 3 (21.4%) | 28 (32.2%) | 0.319 |

| Non-mass | 70 (69.3%) | 11 (78.6%) | 59 (67.8%) | |

| Lesion Location | ||||

| Central | 41 (41.8%) | 8 (61.5%) | 33 (38.8%) | 0.107 |

| Peripheral | 57 (58.2%) | 5 (38.5%) | 52 (61.2%) | |

| Multiplicity | ||||

| Single | 75 (74.3%) | 11 (78.6%) | 64 (73.6%) | 0.489 |

| Multiple | 26 (25.7%) | 3 (21.4%) | 23 (26.4%) | |

| Echogenicity | ||||

| Hypoechoic | 74 (74.0%) | 10 (71.4%) | 64 (73.6%) | 0.521 |

| Isoechoic | 26 (26.0%) | 4 (28.6%) | 22 (25.3%) | |

| Hyperechoic | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Echo pattern | ||||

| Homogeneous | 38 (37.6%) | 4 (28.6%) | 34 (39.1%) | 0.330 |

| Heterogeneous | 63 (62.4%) | 10 (71.4%) | 53 (60.9%) | |

| Size | ||||

| <1/2 | 61 (60.4%) | 5 (35.7%) | 56 (64.4%) | 0.001 |

| ≥1/2 | 36 (35.6%) | 6 (42.9%) | 30 (34.5%) | |

| Whole breast | 4 (4.0%) | 3 (21.4%) | 1 (25.0%) | |

| Internal Change | ||||

| Cystic/Necrotic | 30 (29.7%) | 1 (7.1%) | 29 (33.3%) | 0.039 |

| No | 71 (70.3%) | 13 (92.9%) | 58 (66.7%) | |

| Vascularity | ||||

| Minimal/Mild | 64 (63.4%) | 12 (85.7%) | 52 (59.8%) | 0.150 |

| Moderate/Severe | 28 (27.7%) | 2 (14.3%) | 26 (29.9%) | |

| No | 9 (8.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (10.3%) | |

| Skin Thickening | ||||

| Yes | 83 (82.2%) | 13 (92.9%) | 70 (80.5%) | |

| No | 18 (17.8%) | 1 (7.1%) | 17 (19.5%) | 0.237 |

| Parenchymal Edema | ||||

| Yes | 89 (88.1%) | 14 (100.0%) | 75 (86.2%) | 0.149 |

| No | 12 (11.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 12 (13.8%) | |

| Nipple Inversion | ||||

| Yes | 17 (16.8%) | 4 (28.6%) | 13 (14.9%) | 0.185 |

| No | 84 (83.2%) | 10 (71.4%) | 74 (85.1%) | |

| Calcifications | ||||

| Yes | 3 (3.0%) | 1 (7.1%) | 2 (2.3%) | 0.364 |

| No | 98 (97.0%) | 13 (92.9%) | 85 (97.7%) | |

| Ductal Change | ||||

| Yes | 33 (32.7%) | 5 (35.7%) | 28 (32.2%) | 0.507 |

| No | 68 (67.3%) | 9 (64.3%) | 59 (67.8%) | |

| Lymphadenopathy | ||||

| Yes | 36 (35.6%) | 8 (57.1%) | 28 (32.2%) | 0.136 |

| Equivocal | 42 (41.6%) | 5 (35.7%) | 37 (42.5%) | |

| No | 23 (22.8%) | 1 (7.1%) | 22 (25.3%) |

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Biopsy-proven benign disease suggesting mastitis (n = 62) | |

| Chronic granulomatous inflammation | 31 (50.0%) |

| Chronic granulomatous inflammation and abscess formation | 11 (17.7%) |

| Inflammation and abscess formation | 12 (19.4%) |

| Inflammation | 8 (12.9%) |

| Biopsy-proven malignancy suggesting IBC (n = 14) | |

| Invasive (n = 13) | |

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 11 (78.6%) |

| Microinvasive ductal carcinoma | 1 (7.1%) |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 1 (7.1%) |

| Non-invasive (n = 1) | |

| Ducal carcinoma in situ | 1 (7.1%) |

| Variables | Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| (mean ± SD) | 1.05 | 1.01–1.09 | |||

| ≥40 years | 10.20 | 2.61–39.86 | 2.76 | 0.25–30.46 | 0.407 |

| <40 years | ref. = 1 | ref. = 1 | |||

| BMI | |||||

| (mean ± SD) | 1.24 | 1.04–1.49 | |||

| Normal weight | ref. = 1 | ||||

| Overweight + Obesity | 999.99 | 0.01–999.99 | |||

| Menopausal Status | |||||

| Premenopause | ref. = 1 | ref. = 1 | |||

| Postmenopause | 9.21 | 2.69–31.61 | 6.48 | 0.40–104.99 | 0.189 |

| Symptom Onset (days ago) | |||||

| (mean ± SD) | 1.07 | 1.03–1.11 | 1.07 | 1.02–1.14 | 0.014 |

| Localized Symptoms | |||||

| Swelling | 6.25 | 1.86–21.01 | 15.24 | 1.68–138.69 | 0.016 |

| Previous Mastitis History | |||||

| Yes | ref. = 1 | ||||

| No | 7.94 | 0.99–63.54 | |||

| Size (US) | |||||

| <1/2 | ref. = 1 | ref. = 1 | |||

| ≥1/2 | 2.24 | 0.63–7.95 | 4.49 | 0.52–38.77 | 0.761 |

| Whole breast | 33.60 | 2.93–385.91 | 43.09 | 0.71–999.99 | 0.129 |

| Internal Change (US) | |||||

| Cystic/Necrotic | ref. = 1 | ||||

| No | 6.90 | 0.81–52.63 | |||

| H-W Chisq * | 1.48 | 0.983 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mun, H.S.; Oh, H.Y. Analysis of Clinically Symptomatic Patients to Differentiate Inflammatory Breast Cancer from Mastitis in Asian Women. Life 2025, 15, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15010005

Mun HS, Oh HY. Analysis of Clinically Symptomatic Patients to Differentiate Inflammatory Breast Cancer from Mastitis in Asian Women. Life. 2025; 15(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleMun, Han Song, and Ha Yeun Oh. 2025. "Analysis of Clinically Symptomatic Patients to Differentiate Inflammatory Breast Cancer from Mastitis in Asian Women" Life 15, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15010005

APA StyleMun, H. S., & Oh, H. Y. (2025). Analysis of Clinically Symptomatic Patients to Differentiate Inflammatory Breast Cancer from Mastitis in Asian Women. Life, 15(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/life15010005