Groups of Symmetries of the Two Classes of Synthetases in the Four-Dimensional Hypercubes of the Extended Code Type II

Abstract

:1. Introduction

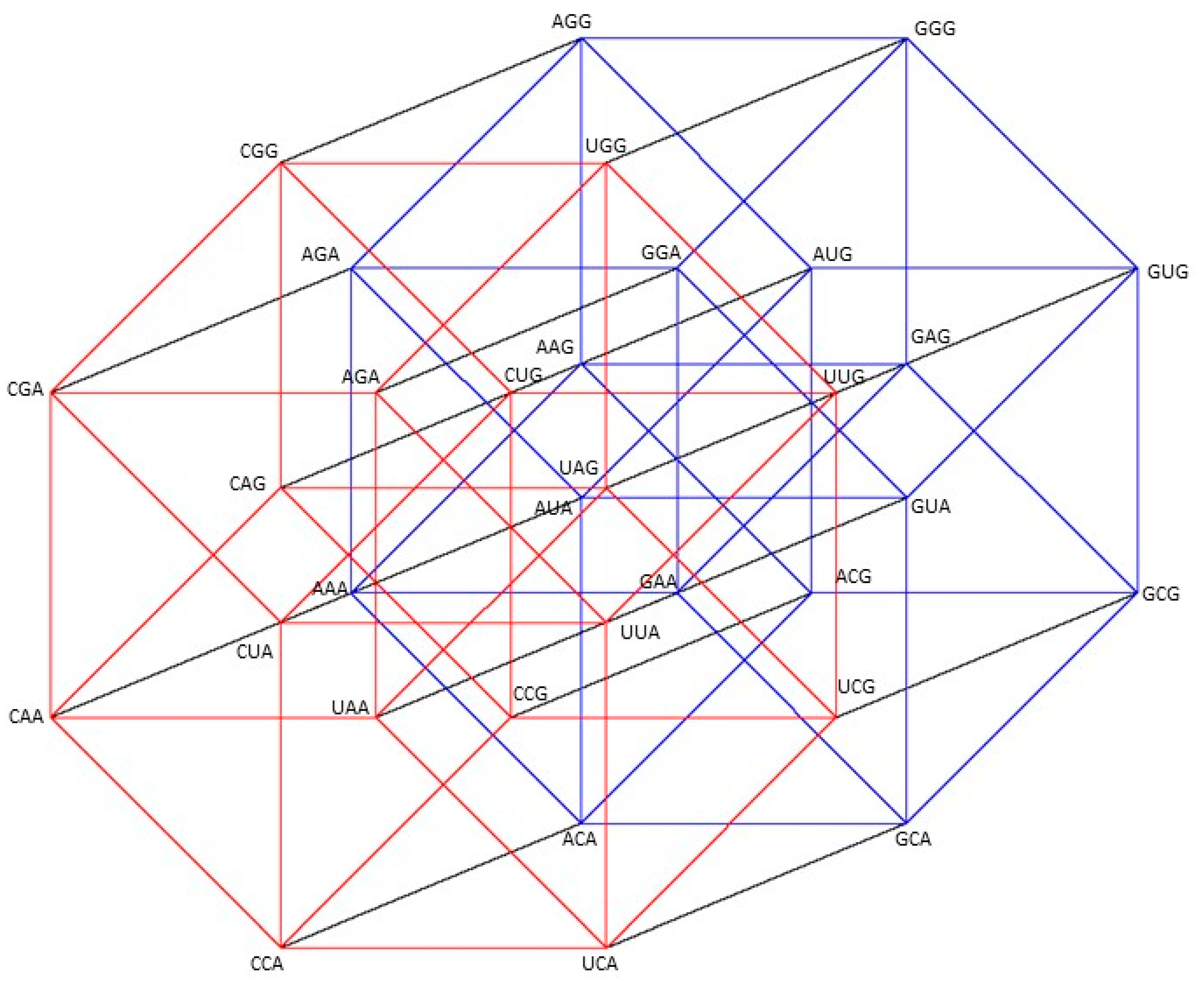

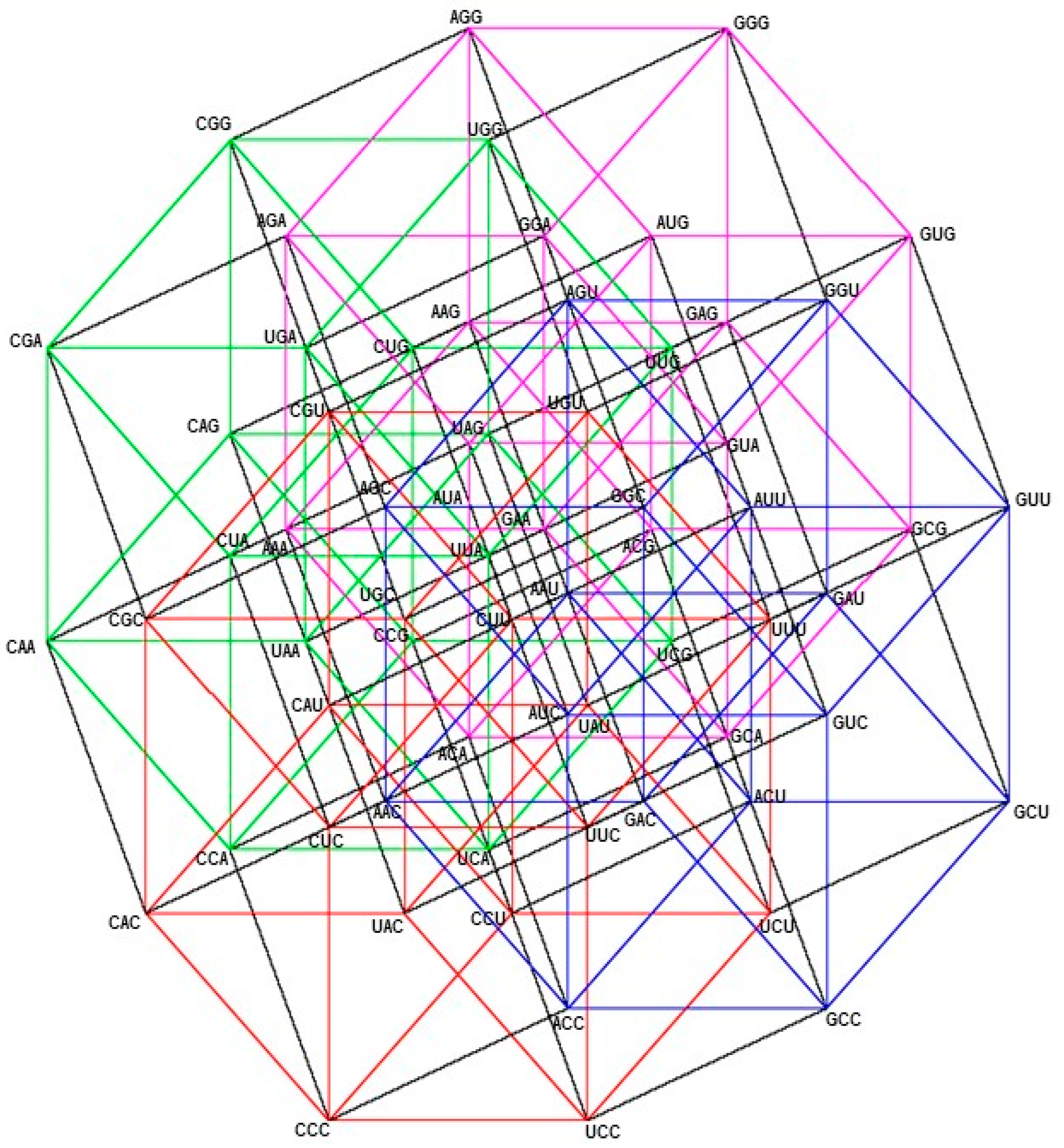

1.1. Basic Mathematics of the SGC

1.2. Arithmetization of the Genetic Code

1.3. The Classes of Synthetases

2. Results

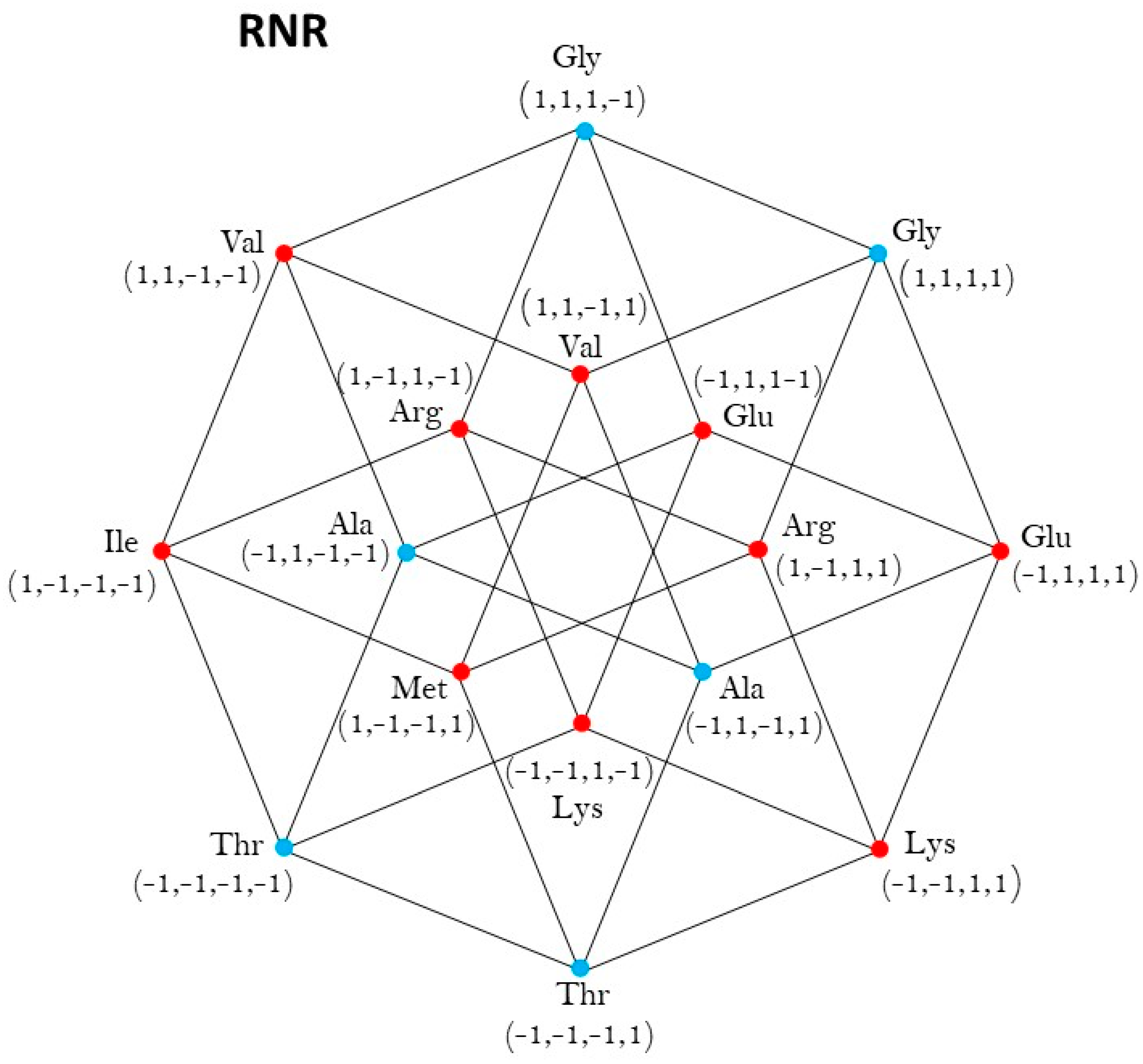

2.1. Group of Symmetries of the Classes of Synthetases in the Hypercube

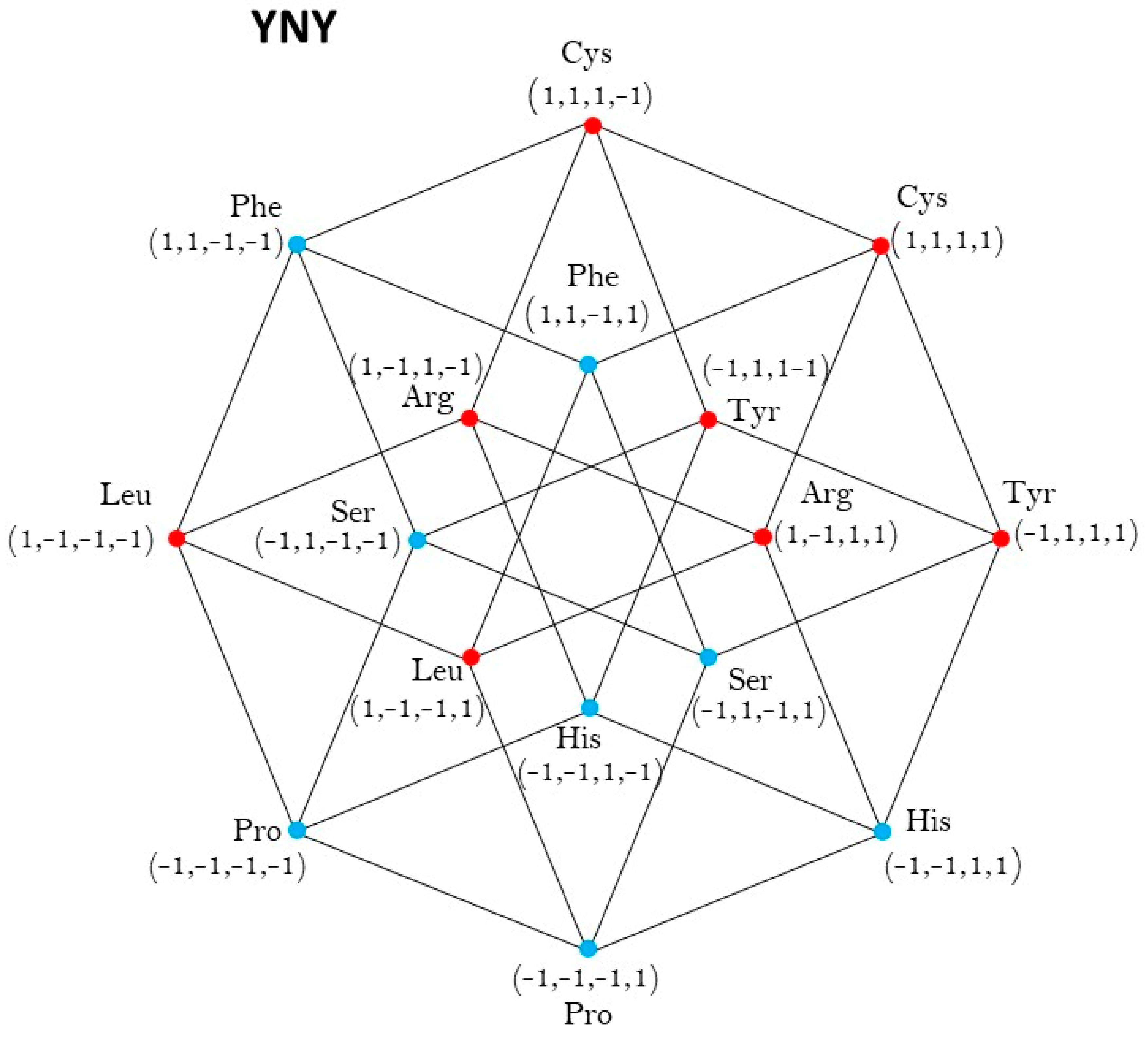

2.2. Group of Symmetries of the Classes of Synthetases in the Hypercube

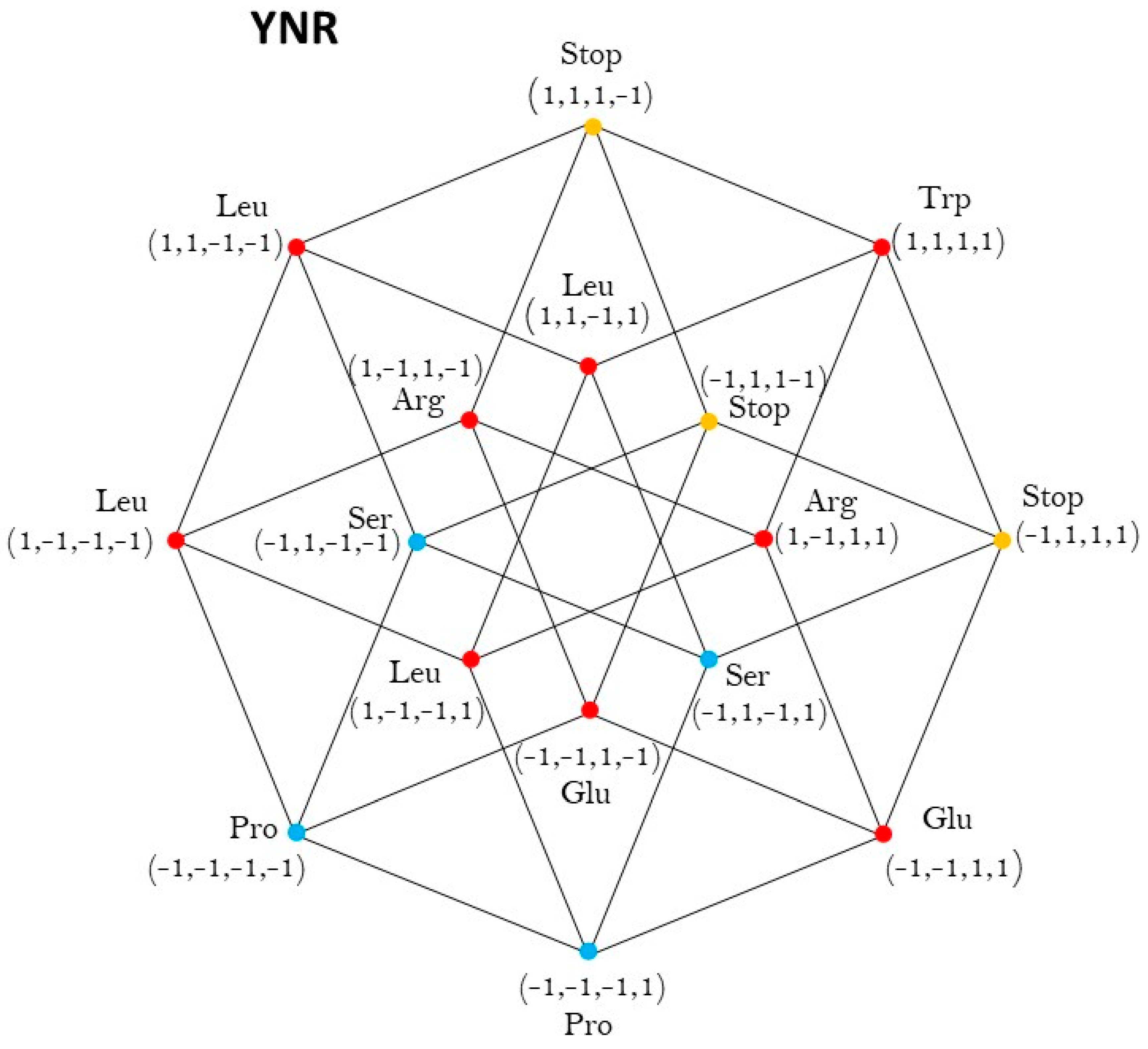

2.3. Group of Symmetries of the Synthetases in the Hypercube

2.4. Group of Symmetries of the Synthetases in the Hypercube

2.5. Conclusions

3. The Genetic Code in 5 and 6 Dimensions

3.1. The Genetic 5-Dimensional Hypercube

3.2. The Hypercube of Dimension 6

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

- for (Mixed associativity).

- for every (Existence of an external neutral element).

- for all (Distributivity of the product with respect to the addition of points, also called distributivity at the left).

- for all (Distributivity of the product with respect to the addition of numbers, also called distributivity at the right.)

References

- Ibba, M.; Söll, D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000, 69, 617–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusack, S.; Berthet-Colominas, C.; Hartlein, M.; Nassar, N.; Leberman, R. A second class of synthetase structure revealed by X-ray analysis of Escherichia coli seryl-tRNA synthetase at 2.5 A. Nature 1990, 347, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriani, G.; Delarue, M.; Poch, O.; Gangloff, J.; Moras, D. Partition of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases into two classes based on mutually exclusive sets of sequence motifs. Nature 1990, 347, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbaum, J.J.; Schimmel, P. Structural relationships and the classification of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 16965–16968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas de Pouplana, L.; Schimmel, P. Two classes of tRNA synthetases suggested by sterically compatible dockings on tRNA acceptor stem. Cell 2001, 104, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas De Pouplana, L.; Schimmel, P. Operational RNA code for amino acids in relation to genetic code in evolution. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 6881–6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas de Pouplana, L. The evolution of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases: From dawn to LUCA. In Enzymes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 48, pp. 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmel, P.; Giege, R.; Moras, D.; Yokoyama, S. An operational RNA code for amino acids and possible relation to genetic code. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 8763–8768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- José, M.V.; Bobadilla, J.R.; Zamudio, G.S.; Farías, S.T. Symmetrical Distributions of Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetases during the evolution of the Genetic Code. Theory Biosci. 2023, 142, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, M.V.; Morgado, E.R.; Govezensky, T. An extended RNA code and its relationship to the standard genetic code: An algebraic and geometrical approach. Bull. Math. Biol. 2007, 69, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- José, M.V.; Morgado, E.R.; Govezensky, T. Genetic Hotels for the Standard Genetic Code: Evolutionary Analysis based upon Novel Three-dimensional Algebraic Models. Bull. Math. Biol. 2011, 73, 1443–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirenberg, M.W.; Matthaei, J.H. The dependance of cell-free protein synthesis in E. coli upon naturally occurring or synthetic polyribonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1961, 47, 1588–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagel, G.M.; Doolittle, R.F. Phylogenetic analysis of the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Mol. Evol. 1995, 40, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woese, C.R.; Olsen, G.J.; Ibba, M.; Söll, D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, the genetic code, and the evolutionary process. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 202–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodin, S.N.; Ohno, S. Two types of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases originally encoded by complementary strands of the same nucleic acid. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 1995, 25, 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodin, S.N.; Rodin, A.S. On the origin of the genetic code: Signatures of its primordial complementarity in tRNAs and Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases. Heredity 2008, 100, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodin, A.S.; Rodin, S.N.; Carter, C.W. On primordial sense–antisense coding. J. Mol. Evol. 2009, 69, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, C.W., Jr.; Li, L.; Weinreb, V.; Collier, M.; Gonzalez-Rivera, K.; Jimenez-Rodriguez, M.; Erdogan, O.; Kuhlman, B.; Ambroggio, X.; Williams, T.; et al. The Rodin-Ohno hypothesis that two enzyme superfamilies descended from one ancestral gene: An unlikely scenario for the origins of translation that will not be dismissed. Biol. Direct. 2014, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- José, M.V.; Zamudio, G.S.; Morgado, E.R. A unified model of the standard genetic code. R Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 160908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Farias, S.T.; Prosdocimi, F.; Caponi, G. Organic Codes: A Unifying Concept for Life. Acta Biotheor. 2021, 69, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethuraman, B.A. Rings, Fields, and Vector Spaces; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

| 5D NNY | 5D NNR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4D RNY | 4D YNY | 4D YNR | 4D RNR |

| ACC | CCC | CCA | ACA |

| Thr ** | Pro ** | Pro ** | Thr ** |

| ACU | CCU | CCG | ACG |

| Thr ** | Pro ** | Pro ** | Thr ** |

| AUC | CUC | CUA | AUA |

| Ile * | Leu * | Leu * | Ile * |

| AUU | CUU | CUG | AUG |

| Ile * | Leu * | Leu * | Met * |

| AAC | CAC | CAA | AAA |

| Asn ** | His ** | Gln * | Lys * |

| AAU | CAU | CAG | AAG |

| Asn ** | His ** | Gln * | Lys * |

| AGC | CGC | CGA | AGA |

| Ser ** | Arg * | Arg * | Arg * |

| AGU | CGU | CGG | AGG |

| Ser ** | Arg * | Arg * | Arg * |

| GCC | UCC | UCA | GCA |

| Ala ** | Ser ** | Ser ** | Ala ** |

| GCU | UCU | UCG | GCG |

| Ala ** | Ser ** | Ser ** | Ala ** |

| GUC | UUC | UUA | GUA |

| Val * | Phe ** | Leu * | Val * |

| GUU | UUU | UUG | GUG |

| Val * | Phe ** | Leu * | Val * |

| GAC | UAC | UAA | GAA |

| Asp ** | Tyr * | Stop | Glu * |

| GAU | UAU | UAG | GAG |

| Asp ** | Tyr * | Stop | Glu * |

| GGC | UGC | UGA | GGA |

| Gly ** | Cys * | Stop | Gly ** |

| GGU | UGU | UGG | GGG |

| Gly ** | Cys * | Trp * | Gly ** |

| 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| C | U | A | G | |

| C | C | U | A | G |

| U | U | U | G | A |

| A | A | G | C | U |

| G | G | A | U | C |

| Class 1 | Class 2 |

|---|---|

| 1a{MetRS, ValRS, LeuRS, IleRS, CysRS, ArgRS | 2a{SerRS, ThrRS, AlaRS, GlyRS-α2, ProRS, HisRS |

| 1b{GluRS, GlnRS, LysRS | 2b{AspRS, AsnRS, LysRS |

| 1c{TyrRS, TrpRS | 2c{PheRS, GlyRS-α2β2, SepRS, PylRS |

| Hypercube | Group of Symmetries |

|---|---|

| RNY | |

| YNY | ℤ2 |

| YNR | Oh |

| RNR | ℤ2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

José, M.V.; Morgado, E.R.; Bobadilla, J.R. Groups of Symmetries of the Two Classes of Synthetases in the Four-Dimensional Hypercubes of the Extended Code Type II. Life 2023, 13, 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13102002

José MV, Morgado ER, Bobadilla JR. Groups of Symmetries of the Two Classes of Synthetases in the Four-Dimensional Hypercubes of the Extended Code Type II. Life. 2023; 13(10):2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13102002

Chicago/Turabian StyleJosé, Marco V., Eberto R. Morgado, and Juan R. Bobadilla. 2023. "Groups of Symmetries of the Two Classes of Synthetases in the Four-Dimensional Hypercubes of the Extended Code Type II" Life 13, no. 10: 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13102002

APA StyleJosé, M. V., Morgado, E. R., & Bobadilla, J. R. (2023). Groups of Symmetries of the Two Classes of Synthetases in the Four-Dimensional Hypercubes of the Extended Code Type II. Life, 13(10), 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13102002