Long- and Short-Term Exposures to PM10 Can Shorten Telomere Length in Individuals Affected by Overweight and Obesity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

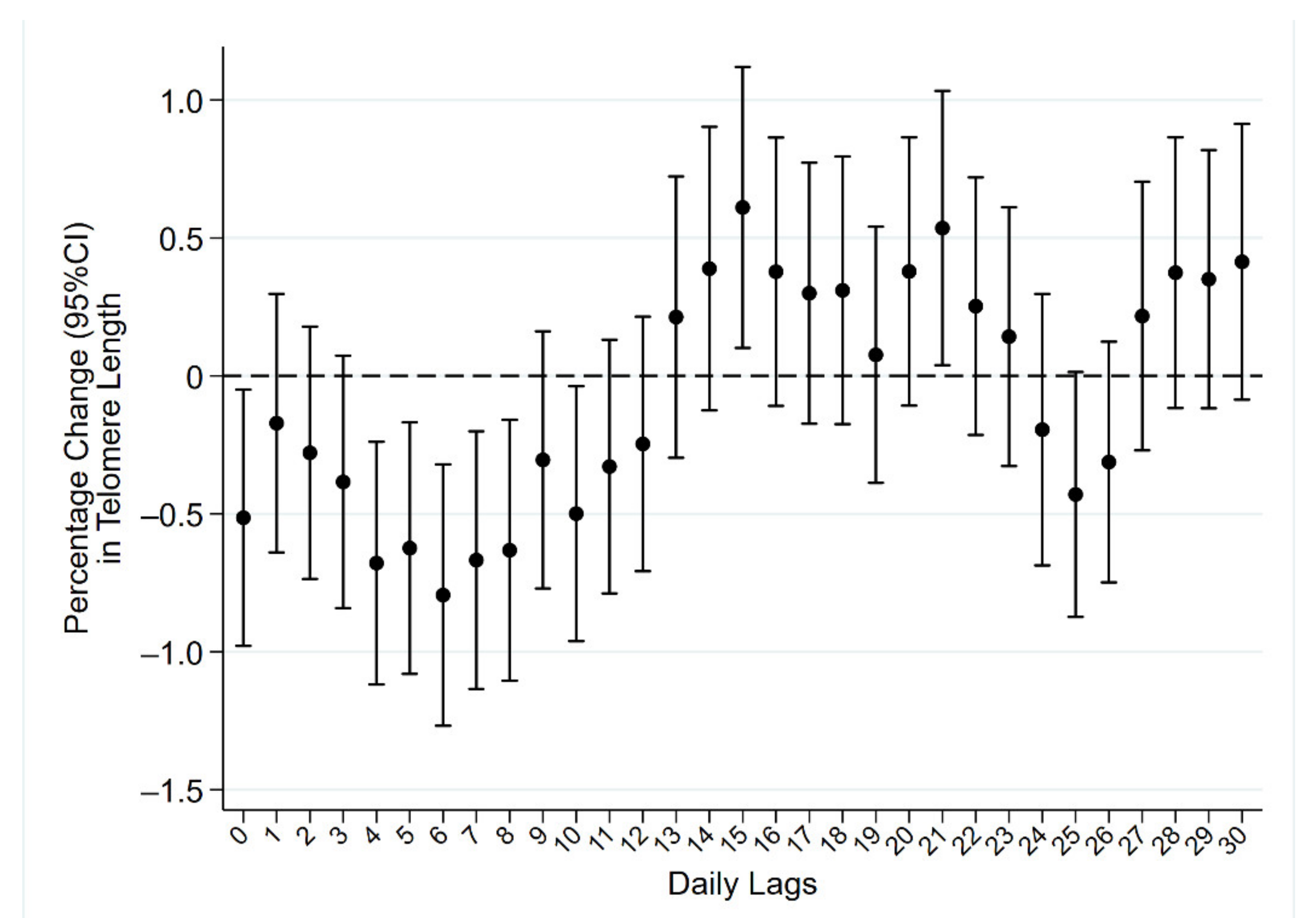

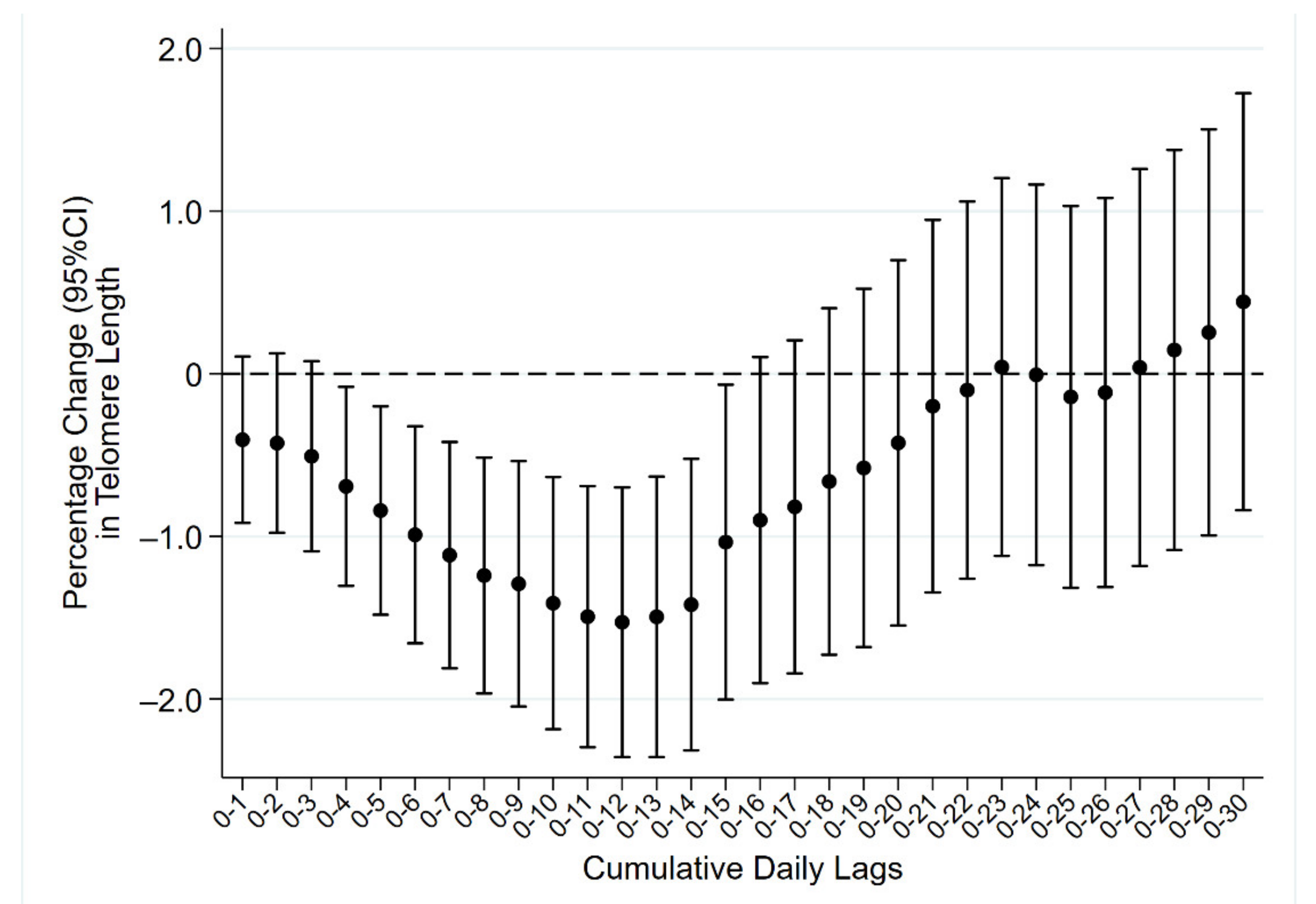

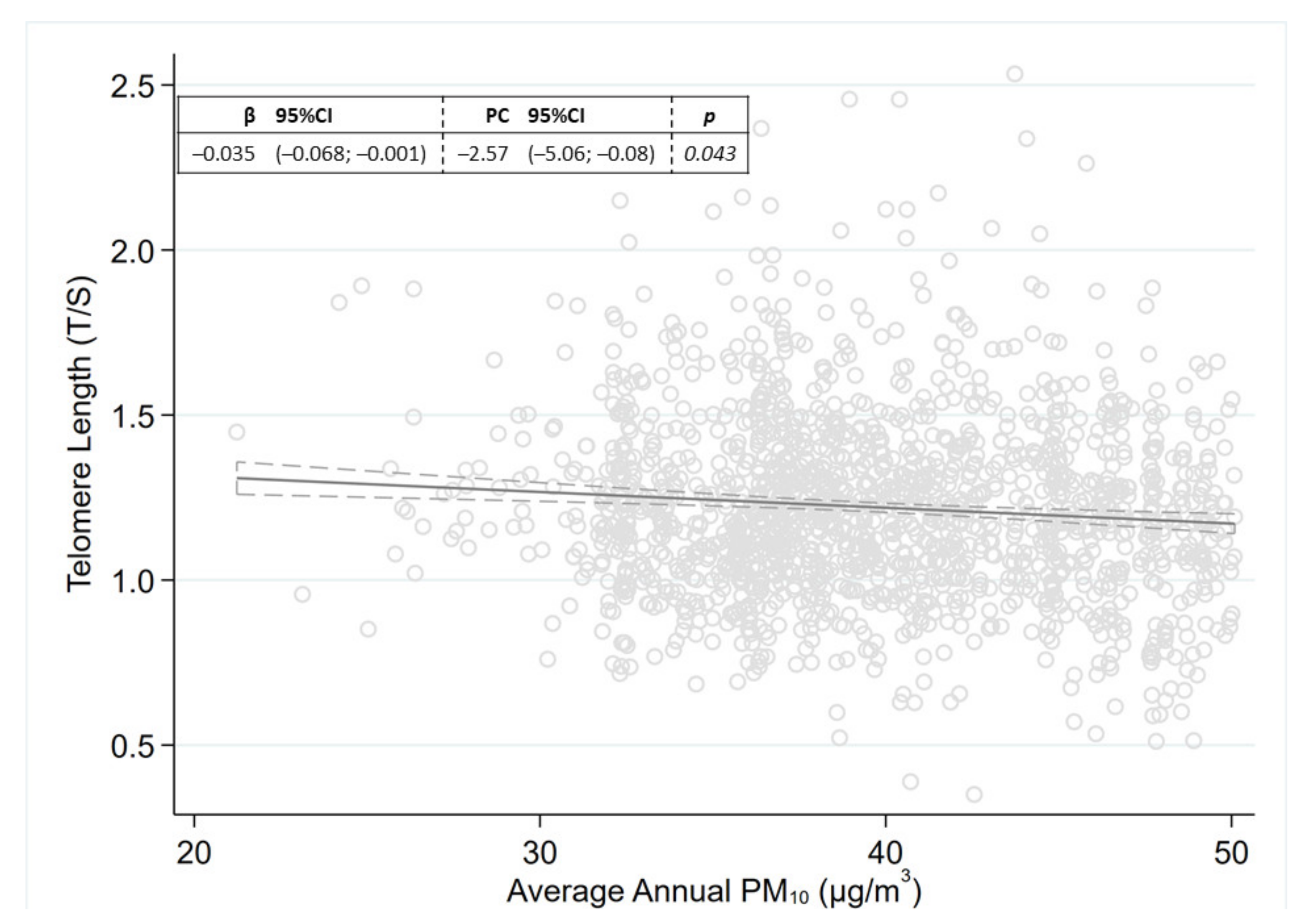

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Collection of Personal Data and Biological Samples

4.3. Exposure Assessment

4.4. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nishimura, K.K.; Galanter, J.M.; Roth, L.A.; Oh, S.S.; Thakur, N.; Nguyen, E.A.; Thyne, S.; Farber, H.J.; Serebrisky, D.; Kumar, R.; et al. Early-Life air pollution and asthma risk in minority children the GALA II and SAGE II studies. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, E.H. Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell 2001, 106, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackburn, E.H. Structure and function of telomeres. Nature 1991, 350, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greider, C.W.; Blackburn, E.H. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in tetrahymena extracts. Cell 1985, 43, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, A.; De Vivo, I.; Liu, Y.; Han, J.; Prescott, J.; Hunter, D.J.; Rimm, E.B. Associations between diet, lifestyle factors, and telomere length in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1273–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mirabello, L.; Huang, W.Y.; Wong, J.Y.Y.; Chatterjee, N.; Reding, D.; Crawford, E.D.; De Vivo, I.; Hayes, R.B.; Savage, S.A. The association between leukocyte telomere length and cigarette smoking, dietary and physical variables, and risk of prostate cancer. Aging Cell 2009, 8, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Lange, T. Telomere-related genome instability in cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2005, 70, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; Amos, C.I.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Grossman, B.H.; Shay, J.W.; Luo, S.; Hong, W.K.; Spitz, M.R. Telomere dysfunction: A potential cancer predisposition factor. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haycock, P.C.; Heydon, E.E.; Kaptoge, S.; Butterworth, A.S.; Thompson, A.; Willeit, P. Leucocyte telomere length and risk of cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014, 349, g4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, L.; Luchini, C.; Demurtas, J.; Soysal, P.; Stubbs, B.; Hamer, M.; Nottegar, A.; Lawlor, R.T.; Lopez-Sanchez, G.F.; Firth, J.; et al. Telomere length and health outcomes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Zglinicki, T. Oxidative stress shortens telomeres. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002, 27, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Omaye, S.T. Air pollutants, oxidative stress and human health. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2009, 674, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A.; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Consonni, D.; Carugno, M.; De Matteis, S.; Nordio, F.; Randi, G.; Bazzano, M.; Caporaso, N.E.; Tucker, M.A.; Bertazzi, P.A.; Pesatori, A.C.; et al. Outdoor particulate matter (PM10) exposure and lung cancer risk in the EAGLE study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carugno, M.; Consonni, D.; Randi, G.; Catelan, D.; Grisotto, L.; Bertazzi, P.A.; Biggeri, A.; Baccini, M. Air pollution exposure, cause-specific deaths and hospitalizations in a highly polluted italian region. Environ. Res. 2016, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Atkinson, R.W.; Kang, S.; Anderson, H.R.; Mills, I.C.; Walton, H.A. Epidemiological time series studies of PM2.5 and daily mortality and hospital admissions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2014, 69, 660–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Requia, W.J.; Adams, M.D.; Arain, A.; Papatheodorou, S.; Koutrakis, P.; Mahmoud, M. Global association of air pollution and cardiorespiratory diseases: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and investigation of modifier variables. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, S123–S130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, M.; Nazarzadeh, M.; Alahabadi, A.; Ehrampoush, M.H.; Rad, A.; Lotfi, M.H.; Sheikhha, M.H.; Sakhvidi, M.J.Z.; Nawrot, T.S.; Dadvand, P. Air pollution and telomere length in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 244, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Wang, S.; Dou, C.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Avula, U.; Hoxha, M.; Díaz, A.; McCracken, J.; et al. Air pollution exposure and telomere length in highly exposed subjects in Beijing, China: A repeated-measure study. Environ. Int. 2012, 48, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dioni, L.; Hoxha, M.; Nordio, F.; Bonzini, M.; Tarantini, L.; Albetti, B.; Savarese, A.; Schwartz, J.; Bertazzi, P.A.; Apostoli, P.; et al. Effects of short-term exposure to inhalable particulate matter on telomere length, telomerase expression, and telomerase methylation in steel workers. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hoxha, M.; Dioni, L.; Bonzini, M.; Pesatori, A.C.; Fustinoni, S.; Cavallo, D.; Carugno, M.; Albetti, B.; Marinelli, B.; Schwartz, J.; et al. Association between leukocyte telomere shortening and exposure to traffic pollution: A cross-sectional study on traffic officers and indoor office workers. Environ. Health 2009, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wong, J.Y.Y.; De Vivo, I.; Lin, X.; Christiani, D.C. Cumulative PM2.5 exposure and telomere length in workers exposed to welding fumes. J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. Part A Curr. Issues 2014, 77, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCracken, J.; Baccarelli, A.; Hoxha, M.; Dioni, L.; Melly, S.; Coull, B.; Suh, H.; Vokonas, P.; Schwartz, J. Annual ambient black carbon associated with shorter telomeres in elderly men: Veterans affairs normative aging study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pieters, N.; Janssen, B.G.; Dewitte, H.; Cox, B.; Cuypers, A.; Lefebvre, W.; Smeets, K.; Vanpoucke, C.; Plusquin, M.; Nawrot, T.S. Biomolecular markers within the core axis of aging and particulate air pollution exposure in the elderly: A cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tam, B.T.; Morais, J.A.; Santosa, S. Obesity and ageing: Two sides of the same coin. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e12991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bollati, V.; Iodice, S.; Favero, C.; Angelici, L.; Albetti, B.; Cacace, R.; Cantone, L.; Carugno, M.; Cavalleri, T.; De Giorgio, B.; et al. Susceptibility to particle health effects, miRNA and exosomes: Rationale and study protocol of the SPHERE study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonzini, M.; Pergoli, L.; Cantone, L.; Hoxha, M.; Spinazzè, A.; Del Buono, L.; Favero, C.; Carugno, M.; Angelici, L.; Broggi, L.; et al. Short-term particulate matter exposure induces extracellular vesicle release in overweight subjects. Environ. Res. 2017, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pergoli, L.; Cantone, L.; Favero, C.; Angelici, L.; Iodice, S.; Pinatel, E.; Hoxha, M.; Dioni, L.; Letizia, M.; Albetti, B.; et al. Extracellular vesicle-packaged miRNA release after short-term exposure to particulate matter is associated with increased coagulation. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, C.; Cai, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Qian, J.; Kan, H. Ambient air pollution, blood mitochondrial DNA copy number and telomere length in a panel of diabetes patients. Inhal. Toxicol. 2015, 27, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, D.S.; Nawrot, T.S. Air pollution stress and the aging phenotype: The telomere connection. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2016, 3, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, S.; Saretzki, G.; Von Zglinicki, T. Preferential accumulation of single-stranded regions in telomeres of human fibroblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 1998, 239, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J.; Khreis, H.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Gascon, M.; Dadvand, P. Fifty shades of green: Pathway to healthy urban living. Epidemiology 2017, 28, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blasco, M.A. Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanova, B.; Riedlova, P.; Dalecka, A.; Jirik, V.; Janout, V.; Sram, R.J. Air pollution and molecular changes in age-related diseases. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.; Schikowski, T.; Carsin, A.E.; Cai, Y.; Jacquemin, B.; Sanchez, M.; Vierkötter, A.; Marcon, A.; Keidel, D.; Sugiri, D.; et al. Adult lung function and long-term air pollution exposure. ESCAPE: A multicentre cohort study and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carugno, M.; Lagazio, C.; Baccini, M.; Consonni, D.; Bertazzi, P.A.; Biggeri, A. Fine airborne particles: When alarming levels are the standard. Public Health 2017, 143, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumeng, C.N.; Bodzin, J.L.; Saltiel, A.R. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, Y.-A. How does obesity and physical activity affect aging? Focused on telomere as a biomarker of aging. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 28, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cawthon, R.M. Telomere length measurement by a novel monochrome multiplex quantitative PCR method. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ridout, K.K.; Levandowski, M.; Ridout, S.J.; Gantz, L.; Goonan, K.; Palermo, D.; Price, L.H.; Tyrka, A.R. Early life adversity and telomere length: A meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iodice, S.; Hoxha, M.; Ferrari, L.; Carbone, I.F.; Anceschi, C.; Miragoli, M.; Pesatori, A.C.; Persico, N.; Bollati, V. Particulate air pollution, blood mitochondrial DNA copy number, and telomere length in mothers in the first trimester of pregnancy: Effects on fetal growth. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Analitis, A.; Katsouyanni, K.; Biggeri, A.; Baccini, M.; Forsberg, B.; Bisanti, L.; Kirchmayer, U.; Ballester, F.; Cadum, E.; Goodman, P.G.; et al. Effects of cold weather on mortality: Results from 15 European cities within the PHEWE project. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 168, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Characteristic | N (%) | TL Mean ± SD | p * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Females | 1259 (72.8) | 1.04 ± 0.30 | |

| Males | 470 (27.2) | 0.98 ± 0.28 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||

| 18–45 | 527 (30.5) | 1.14 ± 0.30 | |

| 46–60 | 704 (40.7) | 1.02 ± 0.28 | |

| 61+ | 498 (28.8) | 0.92 ± 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Education | |||

| None or primary school degree | 141 (8.2) | 0.88 ± 0.25 | |

| Secondary or high school degree | 1278 (73.9) | 1.03 ± 0.29 | |

| University degree or higher | 281 (16.2) | 1.09 ± 0.31 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 29 (1.7) | ||

| BMI (3 cat) | |||

| Overweight (<30) | 458 (26.8) | 1.06 ± 0.32 | |

| Obesity class I (30–34.99) | 651 (38.4) | 1.03 ± 0.29 | |

| Obesity class II and III (≥35) | 580 (34.6) | 1.00 ± 0.27 | 0.001 |

| Missing | 3 (0.2) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| No | 549 (31.7) | 1.04 ± 0.28 | |

| Yes | 648 (37.5) | 1.03 ± 0.30 | 0.738 |

| Missing | 532 (30.8) | ||

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 845 (48.9) | 1.03 ± 0.29 | |

| Former | 611 (35.3) | 0.99 ± 0.29 | |

| Current | 270 (15.6) | 1.08 ± 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 3 (0.2) | ||

| Pack-years of smoking | |||

| 0 | 845 (48.9) | 1.03 ± 0.29 | |

| 1–19 | 475 (27.5) | 1.08 ± 0.30 | |

| 20–29 | 132 (7.6) | 0.98 ± 0.26 | |

| ≥30 | 195 (11.3) | 0.93 ± 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 82 (4.7) | ||

| Place of living | |||

| City/Suburbs | 1230 (71.2) | 1.02 ± 0.29 | |

| Rural area/Town | 341 (19.7) | 1.06 ± 0.29 | 0.024 |

| Missing | 158 (9.1) | ||

| Type 2 diabetes | |||

| No | 1487 (86.0) | 1.02 ± 0.30 | |

| Yes | 188 (10.9) | 0.92 ± 0.26 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 54 (3.1) | ||

| Metabolic Syndrome | |||

| No | 927 (53.6) | 1.07 ± 0.30 | |

| Yes | 766 (44.3) | 0.98 ± 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Missing | 36 (2.1) | ||

| Cancer | |||

| No | 1656 (95.8) | 1.03 ± 0.29 | |

| Yes | 73 (4.2) | 0.99 ± 0.30 | 0.168 |

| TOTAL | 1729 (100) | 1.03 ± 0.29 | ----- |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carugno, M.; Borroni, E.; Fedrizzi, L.; Hoxha, M.; Vigna, L.; Consonni, D.; Bollati, V.; Pesatori, A.C. Long- and Short-Term Exposures to PM10 Can Shorten Telomere Length in Individuals Affected by Overweight and Obesity. Life 2021, 11, 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11080808

Carugno M, Borroni E, Fedrizzi L, Hoxha M, Vigna L, Consonni D, Bollati V, Pesatori AC. Long- and Short-Term Exposures to PM10 Can Shorten Telomere Length in Individuals Affected by Overweight and Obesity. Life. 2021; 11(8):808. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11080808

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarugno, Michele, Elisa Borroni, Luca Fedrizzi, Mirjam Hoxha, Luisella Vigna, Dario Consonni, Valentina Bollati, and Angela Cecilia Pesatori. 2021. "Long- and Short-Term Exposures to PM10 Can Shorten Telomere Length in Individuals Affected by Overweight and Obesity" Life 11, no. 8: 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11080808

APA StyleCarugno, M., Borroni, E., Fedrizzi, L., Hoxha, M., Vigna, L., Consonni, D., Bollati, V., & Pesatori, A. C. (2021). Long- and Short-Term Exposures to PM10 Can Shorten Telomere Length in Individuals Affected by Overweight and Obesity. Life, 11(8), 808. https://doi.org/10.3390/life11080808