1. Introduction

During the development of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), reliable and energy-efficient altitude control is considered a key requirement, since hover stability and the energy required for actuation directly affect flight endurance, payload capability, and operational safety [

1,

2,

3]. In previous studies, improper battery utilization, performance degradation caused by rapid discharge, and unstable control behavior have been identified as major sources of operational failures and accidents [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Precise altitude holding is particularly critical in application areas such as traffic monitoring, infrastructure inspection, and stationary aerial surveillance, where sustained hovering must be maintained for extended periods [

7,

8,

9].

In both industrial systems and multirotor UAV platforms, classical proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control is applied in approximately 90–97% of cases due to its simplicity and widespread adoption [

10,

11]. However, the sensitivity of PID control to external disturbances, nonlinearities, and model uncertainties frequently leads to inefficient energy usage and reduced flight time [

12,

13,

14,

15]. These limitations highlight the necessity of experimentally investigating advanced control strategies in real physical environments under identical test conditions.

A wide range of modern control approaches for UAV systems has been reported in the literature, including linear quadratic regulation (LQR) [

16], model predictive control (MPC) [

17], sliding mode control (SMC) [

18], backstepping methods [

19], fractional-order PID (FOPID) control [

20], and robust H∞ control [

21]. Although the theoretical benefits and modeling-based results of these approaches are well documented, the number of unified, real-time experimental investigations conducted under identical physical conditions remains limited, particularly in hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) frameworks that enable direct comparison of multiple controllers under the same operating conditions. Consequently, only a limited amount of consistent and directly comparable experimental data is available regarding the practical performance of these methods. HIL systems provide significant advantages in controller design, as they allow the combined evaluation of model uncertainties, delays, sensor noise, nonlinear motor behavior, and actuator constraints. As a result, the practical applicability of the designed controllers can be assessed more accurately than in purely simulation-based environments [

22,

23,

24,

25].

In accordance with this, it can be stated that a significant portion of the investigations reported in the literature are conducted either exclusively in simulation environments or focus on a single selected control method under differing experimental conditions. Studies in which multiple controllers of different structures—linear, nonlinear, robust, and predictive—are compared within a unified hardware environment, using identical reference values, identical disturbance conditions, and identical execution infrastructure, are rarely found [

24,

25]. In particular, the number of experimental works is limited in which altitude-holding performance, robustness, and energy consumption of controllers are investigated on a controlled single-degree-of-freedom test platform within a hardware-in-the-loop environment using a single, unified measurement framework [

24,

25].

The objective of the present study is to address these shortcomings through the application of an HIL-based experimental methodology that enables the direct and comparable real-time evaluation of multiple control methods representing different control philosophies. The present study significantly extends the previous results reported in [

24,

25] by realizing an experimental comparison of seven different linear, nonlinear, robust, and optimization-based control methods within a unified and identical HIL environment. The novelty of the applied approach is provided by the unified experimental framework and by the joint investigation of performance metrics related to energy consumption and robustness. The positioning of the present work relative to related simulation-based, experimental, and HIL-based UAV control studies is summarized in

Table 1.

In the present study, a custom-developed HIL system implemented on a single-degree-of-freedom drone test bench is presented and applied, enabling the objective real-time comparison of seven different control strategies [

24,

25]. The experimental platform is based on a Parrot mini drone frame (Parrot SA, Paris, France)equipped with Parrot Mambo motors (Parrot SA, Paris, France), an ATmega328P (Arduino UNO, Arduino S.r.l., Via Andrea Appiani 25, Monza, Italy) microcontroller, an ACS712 current sensor (Allegro MicroSystems, Manchester, NH, USA), and a VL53L0X laser distance sensor (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland), while the control algorithms are executed in the MATLAB 2023b (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA) environment and the actuation is performed using pulse-width modulation (PWM).

The experiments were conducted under disturbance-free conditions and under wind loading with a velocity of 10 km/h applied from a direction of 45°, in order to evaluate both the energy management characteristics and the disturbance sensitivity of the investigated controllers [

24,

25]. Performance evaluation was carried out based on hover accuracy, settling time, overshoot, and real-time measured power consumption. The objective of the research is to provide a comprehensive comparison of different control strategies in a real HIL environment and to identify which approaches offer the highest stability and energy efficiency in practical UAV applications.

3. Results

This section presents the experimental evaluation of the performance of the different controllers under both disturbance-free conditions and conditions affected by wind loading. For each controller, the results include the real-time altitude response of the drone, shown in blue in the plots, as well as the power–time profile required for hovering, displayed in orange. The results obtained in a disturbance-free environment and under constant wind loading with a velocity of 10 km/h applied at an angle of 45° are both presented, allowing a direct comparison of controller robustness and energy consumption.

3.1. Results of HIL Experiments in a Disturbance-Free Environment

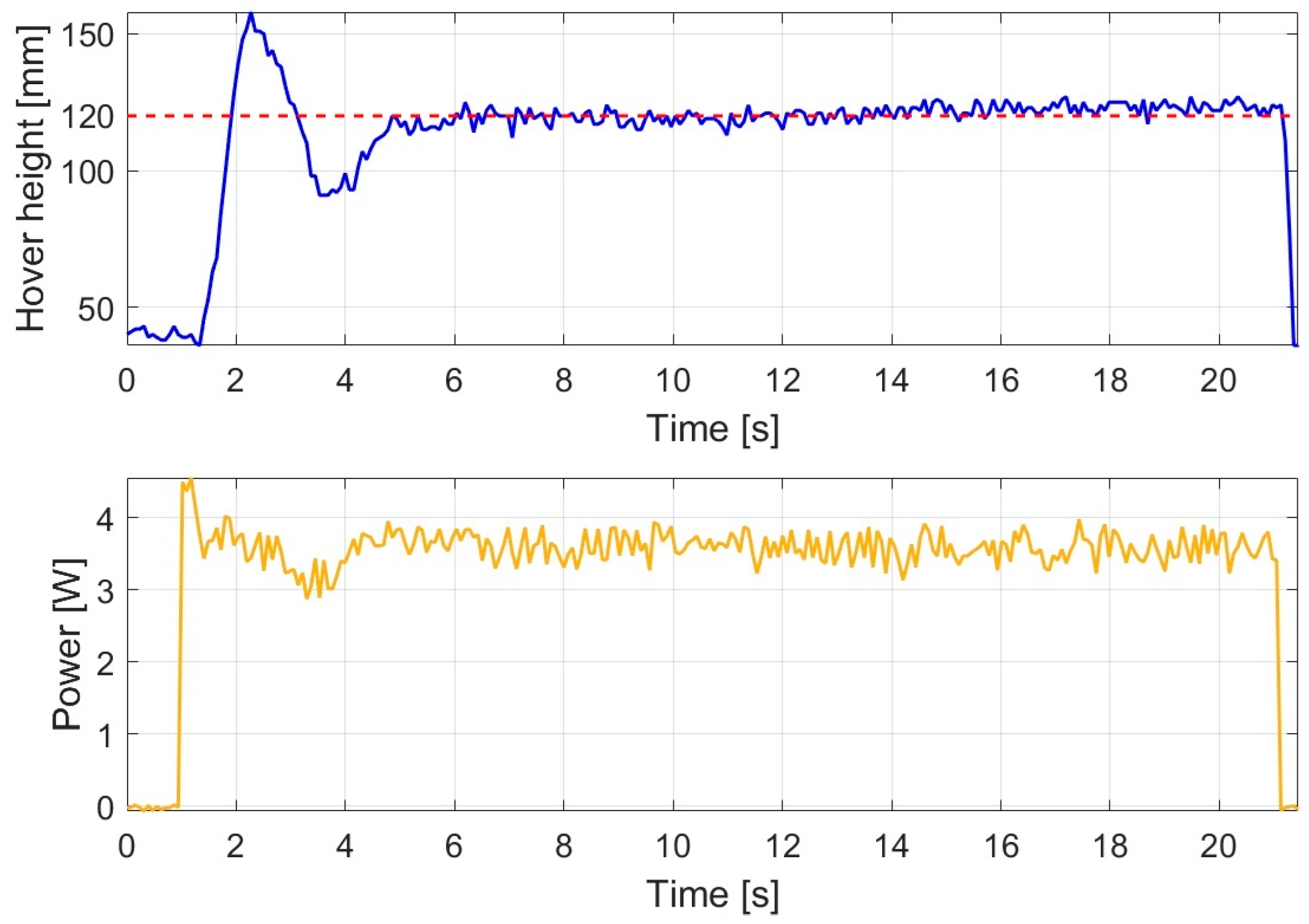

The response of the PID controller under disturbance-free conditions is illustrated in

Figure 2.

The altitude response shows that a pronounced overshoot occurred, during which the drone exceeded the 120 mm reference value up to approximately 158 mm. Following the overshoot, the altitude converged toward the reference with a slowly damped transient, and a stable hovering condition was reached after approximately 4.858 s. During the stabilized phase, the average altitude was 120.793 mm, which can be considered accurate reference tracking.

Based on the power response, the initial rapid ascent was accompanied by a peak power of 4.556 W, reflecting the increased control effort required to produce the large overshoot. During the hovering phase, the average power consumption was 3.584 W, which represents one of the higher values among the investigated controllers for the PID case.

Overall, the PID controller ensured stable reference tracking under disturbance-free conditions; however, due to the significant overshoot, slower damping behavior, and higher energy demand, less favorable dynamic performance was observed compared to the modern control strategies.

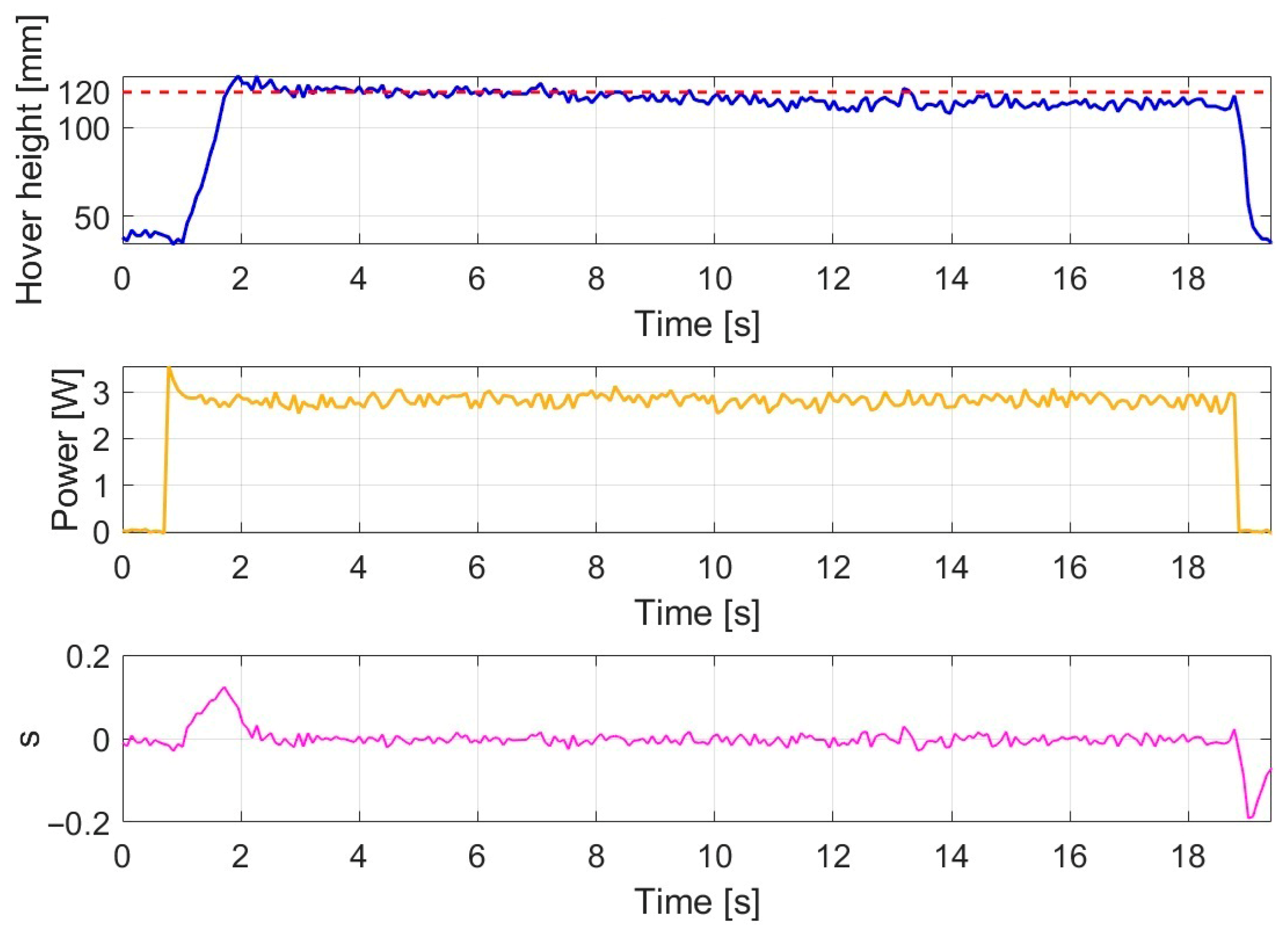

The response of the backstepping controller is shown in

Figure 3.

The altitude response indicates that an overshoot of approximately 152 mm occurred during the rising phase, after which the altitude stabilized rapidly and reached steady-state operation within approximately 3.522 s. During stable hovering, the average altitude was 118.346 mm, showing a small deviation from the 120 mm reference value. The control performance proved to be accurate and stable, without significant oscillations.

In the power response, a peak power of 3.793 W associated with the initial load can be observed, which is lower than the value recorded for the PID controller. The average power consumption during the hovering phase was 3.025 W, which is considerably lower than the energy demand of the PID controller, indicating improved efficiency and more damped actuation dynamics of the backstepping approach.

Overall, under disturbance-free conditions, the backstepping controller provided stable, fast, and energy-efficient altitude control, with more favorable transient behavior compared to the PID controller.

The response of the SMC controller is shown in

Figure 4.

Under disturbance-free conditions, the sliding mode controller provided a fast and decisive transient response. The rising phase exhibited dynamic yet well-damped behavior, and steady-state operation was achieved within approximately 1.953 s, representing one of the shortest settling times among the investigated controllers. During the stable hovering phase, the average altitude was 116.556 mm, indicating a small but consistent negative deviation from the 120 mm reference value. During the rising phase, an initial overshoot of approximately 129 mm was observed, which is significantly lower than the 158 mm overshoot recorded for the classical PID controller, suggesting improved transient behavior.

From an efficiency perspective, the average power consumption of the SMC controller was 2.817 W, which is notably lower than the values observed for both the PID and backstepping controllers. The peak power measured during the initial transient was 3.551 W, further supporting the favorable energy dynamics.

The third (pink) plot illustrates the sliding surface variable s, which represents a key element of SMC operation. The s-trajectory exhibits a brief deviation during the transient phase, followed by rapid convergence into a narrow range where it remains close to zero. This behavior indicates successful entry into the sliding mode and stable maintenance of motion on the sliding surface.

Overall, the SMC controller demonstrated fast settling time, low energy consumption, and good robustness, although the accuracy of the hovering altitude was slightly below the reference value.

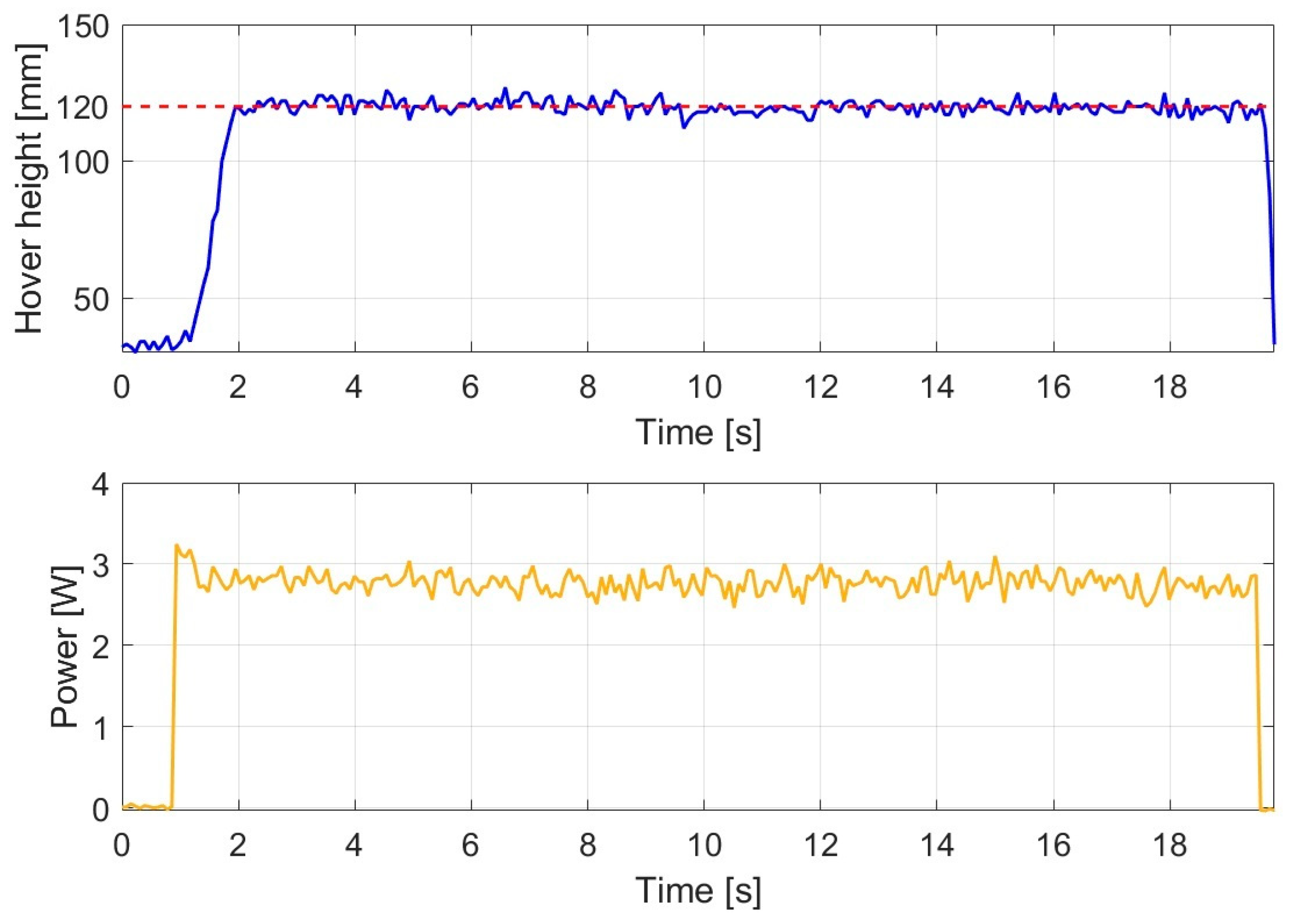

The response of the FOPID controller is shown in

Figure 5.

Under disturbance-free conditions, the FOPID controller provided highly balanced and stable hovering performance. The system reached the hovering state within approximately 1.950 s, representing one of the best settling times among the investigated controllers. During the stable phase, the average altitude was 119.880 mm, indicating excellent accuracy relative to the 120 mm reference value with practically negligible error.

From an energy efficiency perspective, the average power consumption of the FOPID controller was 2.754 W, demonstrating higher efficiency than the PID, backstepping, and SMC controllers. The initial power peak was measured at 3.245 W, after which the power remained stable within a low and uniform range.

Overall, under disturbance-free conditions, the FOPID controller exhibited the most stable and accurate hovering performance while maintaining good energy efficiency and fast settling time.

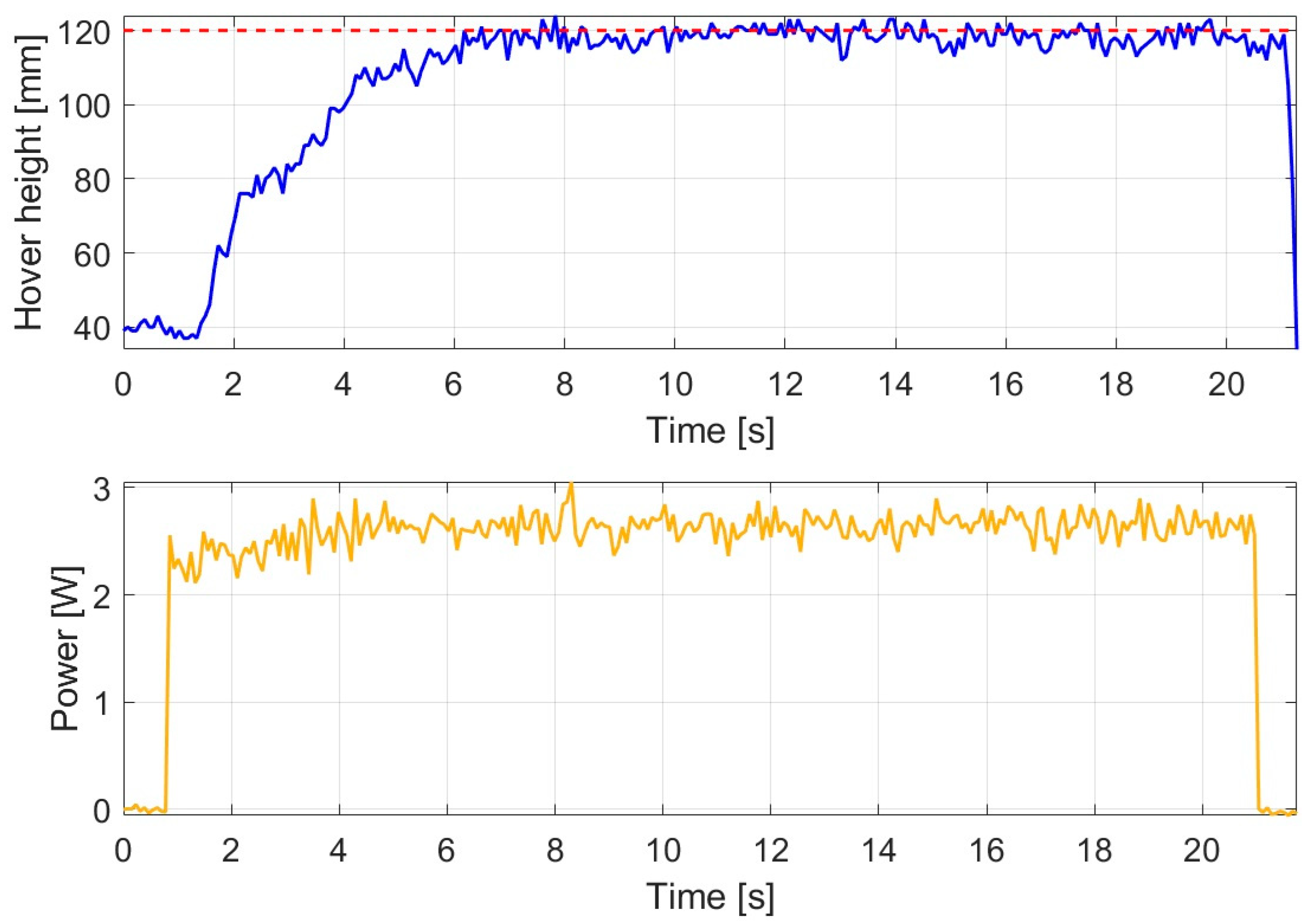

The response of the LQI controller is shown in

Figure 6.

The integrator-augmented LQ controller provided highly accurate reference tracking under disturbance-free conditions. Although the rising phase exhibited slower dynamics compared to the other controllers, the system converged stably toward the reference value. Steady-state operation was achieved after approximately 6.182 s, representing the longest settling time among the investigated control methods; however, outstanding hovering performance and accuracy were obtained.

During the stable hovering phase, the average altitude was 119.891 mm, corresponding to virtually error-free reference tracking.

In terms of energy efficiency, the LQI controller demonstrated one of the most favorable results among the examined methods. The average hovering power was 2.632 W, which is lower than that of the PID controller (3.584 W) and also lower than that of the nonlinear controllers such as backstepping and SMC. The initial power peak reached 2.555 W, which is among the lowest observed values, indicating energy-efficient behavior during the rising phase.

Overall, under disturbance-free conditions, the LQI controller achieved excellent reference tracking, very low energy demand, and stable hovering behavior; however, the settling time was longer than that of other approaches. The observed performance confirms the benefit of incorporating an integral state to eliminate steady-state errors.

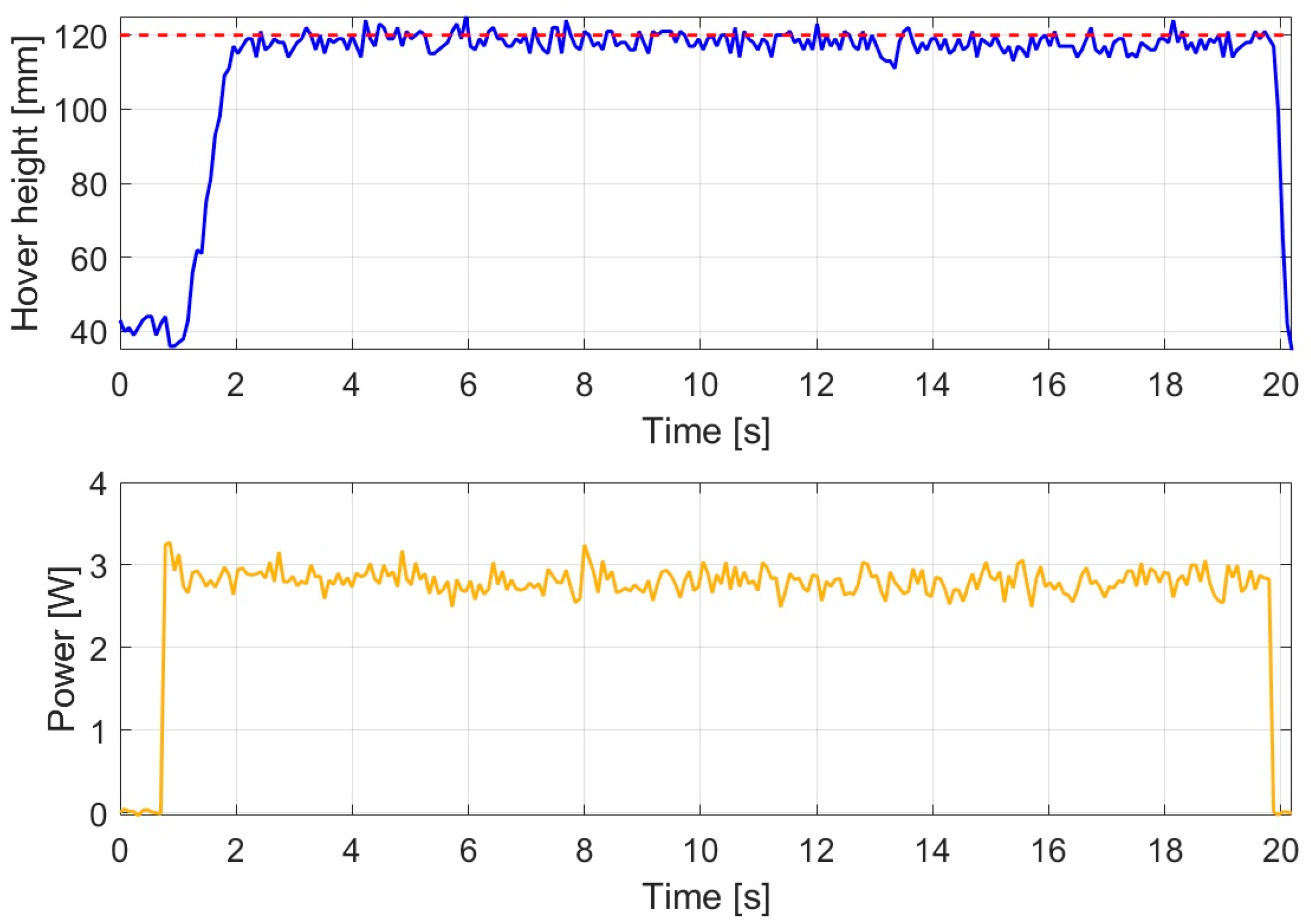

The response of the MPC controller is shown in

Figure 7.

Under disturbance-free conditions, the MPC controller provided fast, stable, and well-damped altitude control. The rising phase was short, and steady-state operation was achieved within approximately 2.110 s, which represents one of the shortest settling times among the investigated methods. The altitude response indicates that the reference value was tracked effectively, resulting in a sustained and stable hovering condition.

During the hovering phase, the average altitude was 118.102 mm, showing a minimal and well-damped deviation from the 120 mm reference value. The control response remained consistently stable, without significant oscillations or periodic fluctuations.

Based on the power profile, the initial power peak of the MPC controller was 3.273 W. The average power consumption during stable hovering was 2.803 W, which is a favorable value and demonstrates improved efficiency compared to the PID, backstepping, and SMC controllers.

Overall, under disturbance-free conditions, the MPC controller demonstrated an excellent compromise between fast settling time, accurate reference tracking, and favorable energy efficiency, while maintaining stable and robust hovering behavior.

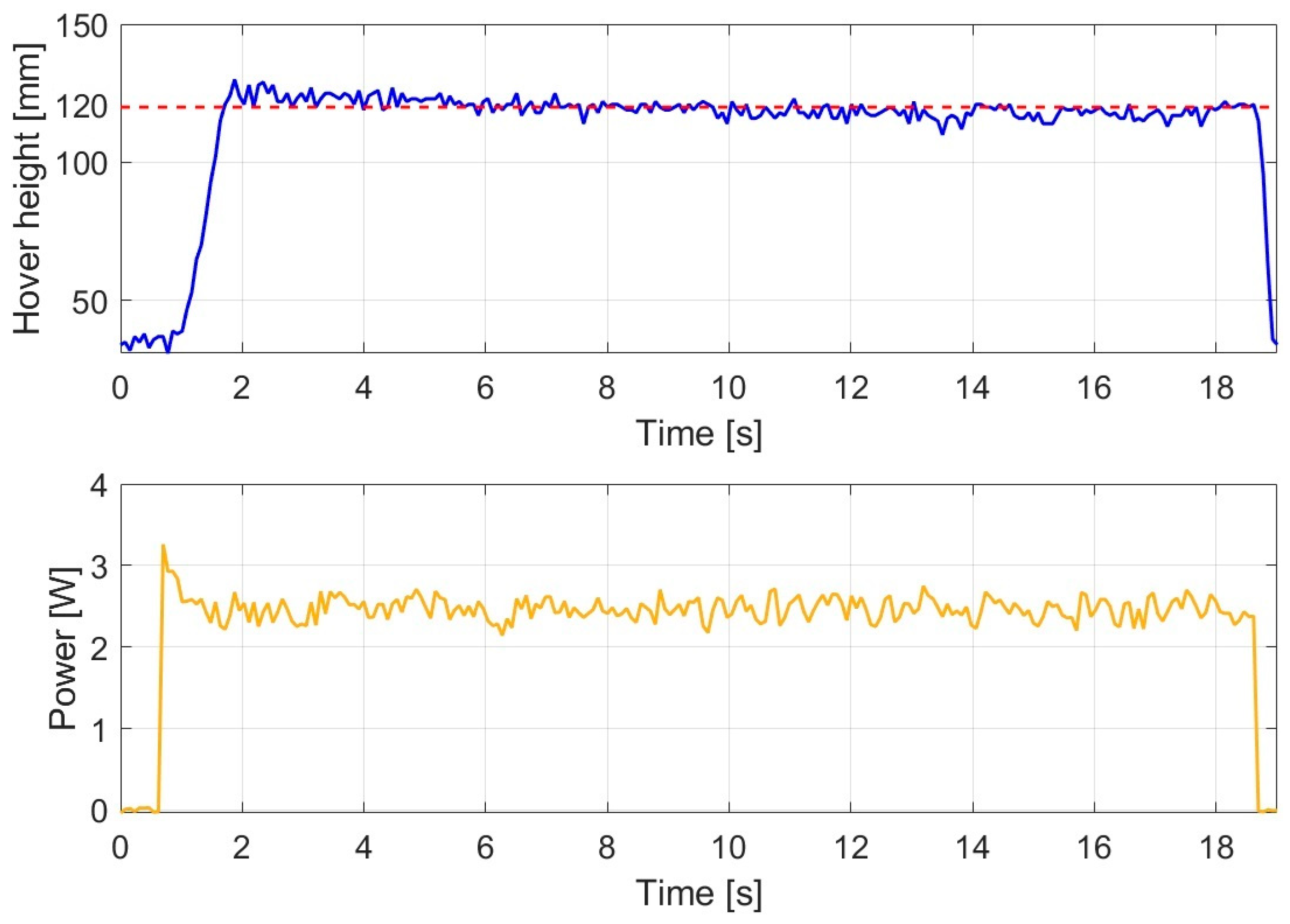

The response of the H∞ controller is shown in

Figure 8.

Under disturbance-free conditions, the H∞ controller exhibited highly stable and energy-efficient hovering performance. Steady-state operation was reached within approximately 2.031 s, representing one of the most favorable settling times among the investigated methods.

During the rising phase, an initial overshoot of approximately 130 mm was observed, which is significantly lower than the 158 mm overshoot measured for the PID controller and slightly higher than that recorded for the SMC controller. Nevertheless, this transient behavior remains acceptable relative to the 120 mm reference value.

In the stable hovering phase, the average altitude was 119.693 mm, indicating excellent reference tracking. The altitude response exhibited smooth and well-damped behavior without large-amplitude oscillations.

From an energy efficiency standpoint, the H∞ controller proved to be one of the most favorable approaches, with an average hovering power consumption of only 2.452 W, which is the lowest value among the investigated controllers. The initial power peak reached 3.259 W, reflecting the control effort required for rapid reference acquisition, after which the power level remained stable at a low value.

The robust structure of the H∞ controller is well suited to the physical characteristics of the test platform and resulted in highly stable and efficient control behavior in the real HIL environment. Based on the experimental results, this method provides an outstanding compromise between fast settling time, excellent reference tracking, and minimal energy consumption.

3.2. Results of HIL Experiments Under Constant Wind Disturbance of 10 km/h

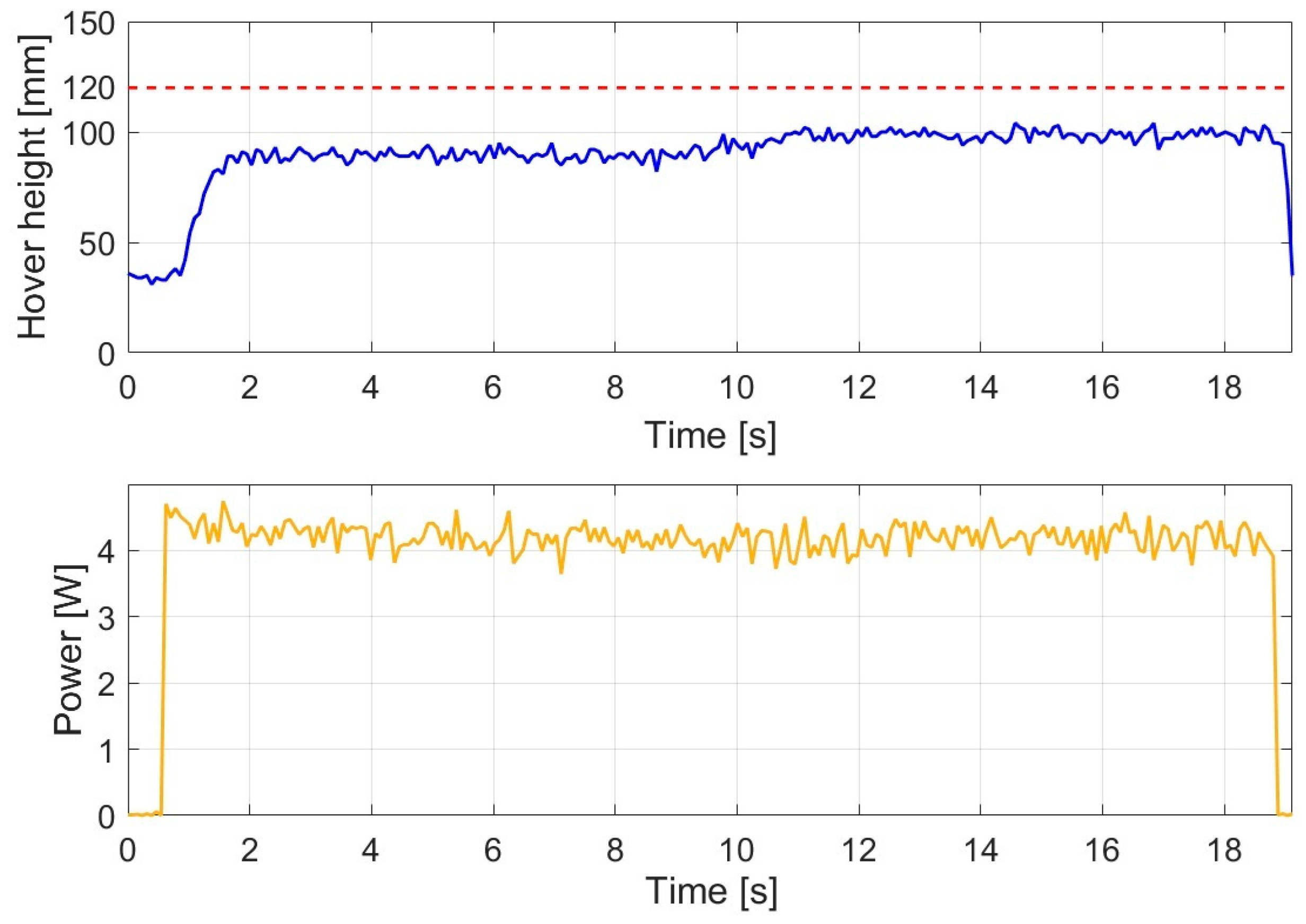

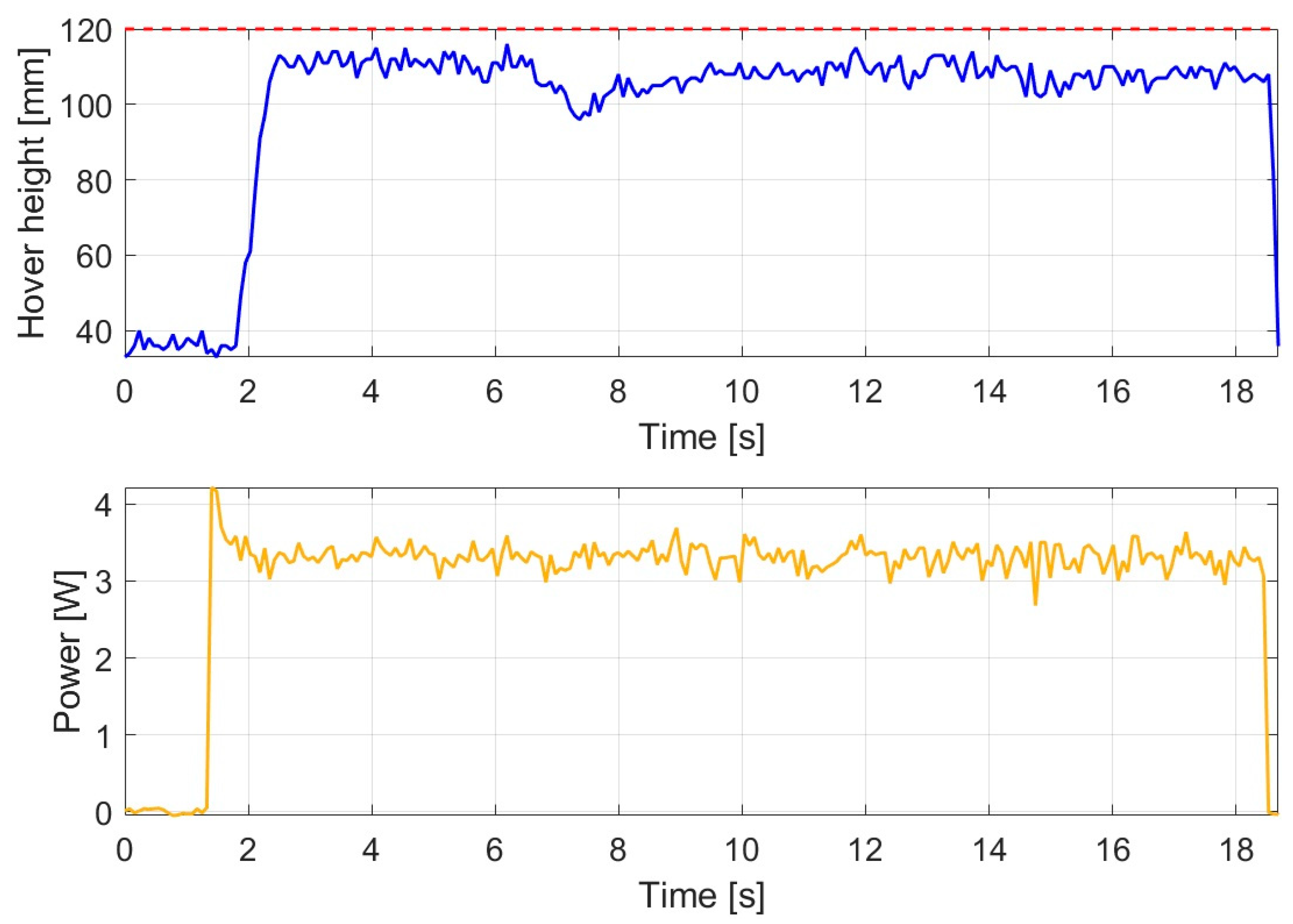

The response of the PID controller under constant wind disturbance is illustrated in

Figure 9.

Under constant wind disturbance with a velocity of 10 km/h applied from above at an angle of 45° relative to the vertical axis, the hovering performance of the PID controller deteriorated significantly compared to the disturbance-free case. The altitude response indicates that the system was unable to reach the 120 mm reference value, during the stabilized phase, the average altitude was only 93.960 mm, representing a substantial and persistent loss of hovering height. The altitude trajectory exhibits increased oscillatory behavior and a “sagging” hovering condition below the reference level.

Due to the wind loading, energy demand also increased, with an average power consumption of 4.155 W during the hovering phase, which is higher than the 3.584 W measured under disturbance-free conditions. Thus, the PID controller responded unfavorably to the constant wind disturbance in terms of both accuracy and energy efficiency.

Overall, it can be concluded that under wind loading, the PID controller operated with significant altitude degradation and increased power demand, clearly demonstrating limited robustness against external disturbances.

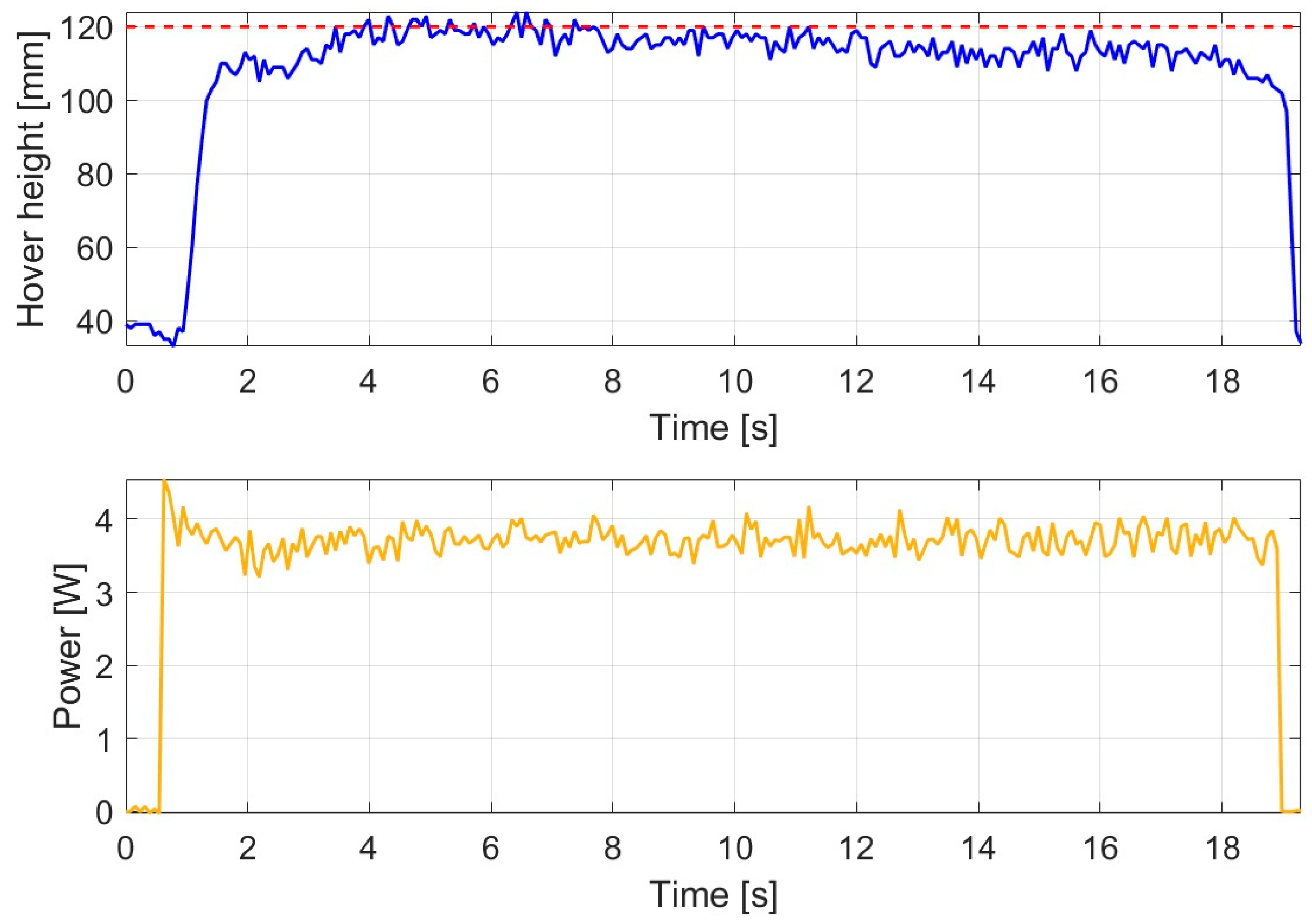

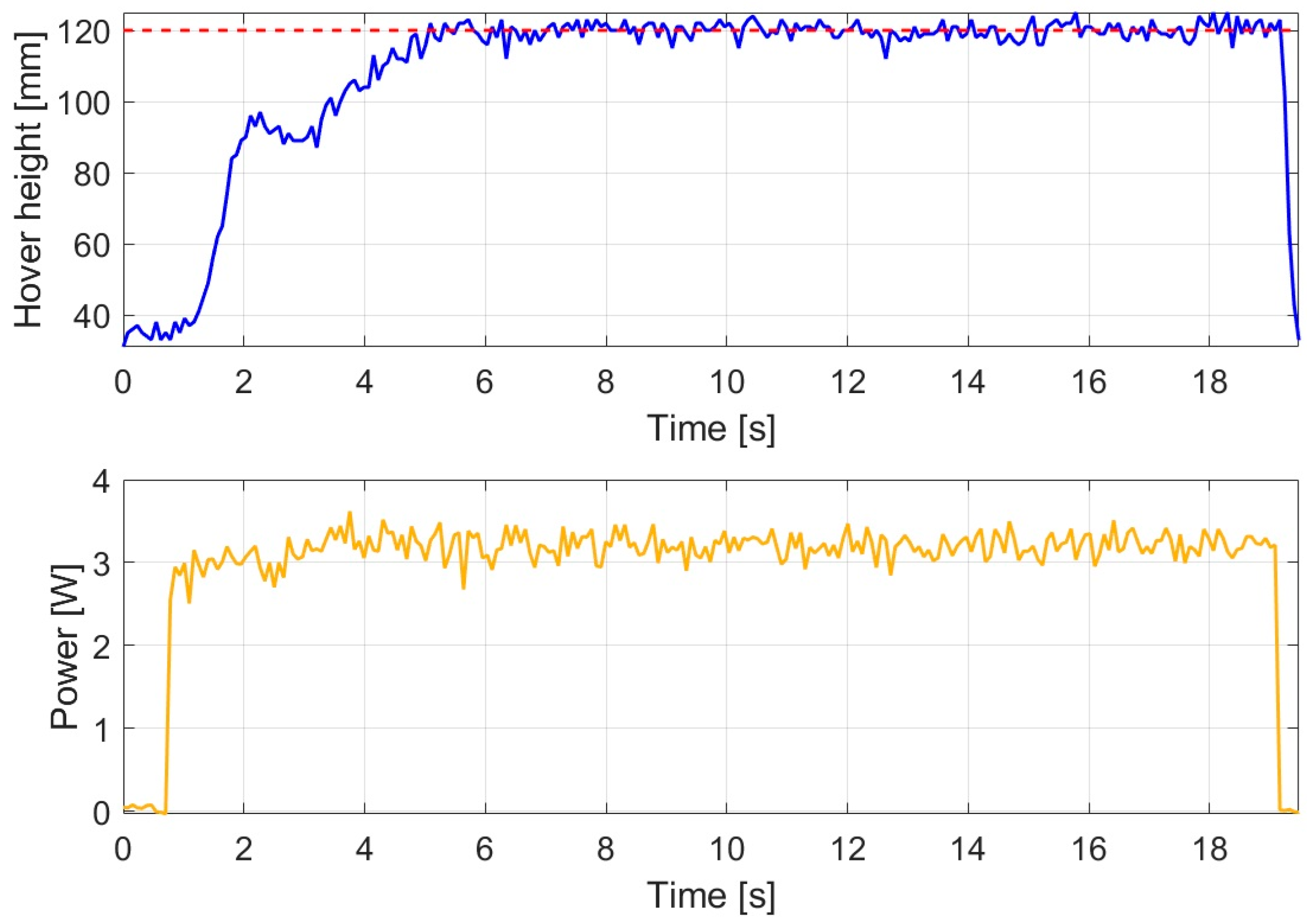

The response of the backstepping controller under constant wind disturbance is illustrated in

Figure 10.

Under constant wind loading of 10 km/h applied at an angle of 45°, the backstepping controller was able to maintain the altitude close to the reference value. During the hovering phase, the average altitude was 114.529 mm, representing a significantly smaller deviation from the 120 mm reference compared to the PID controller. The altitude response exhibited mildly oscillatory behavior.

As a result of the wind disturbance, the average hovering power consumption increased to 3.692 W, which, although higher than in disturbance-free operation, still represents approximately 11% energy savings compared to the PID controller under identical conditions.

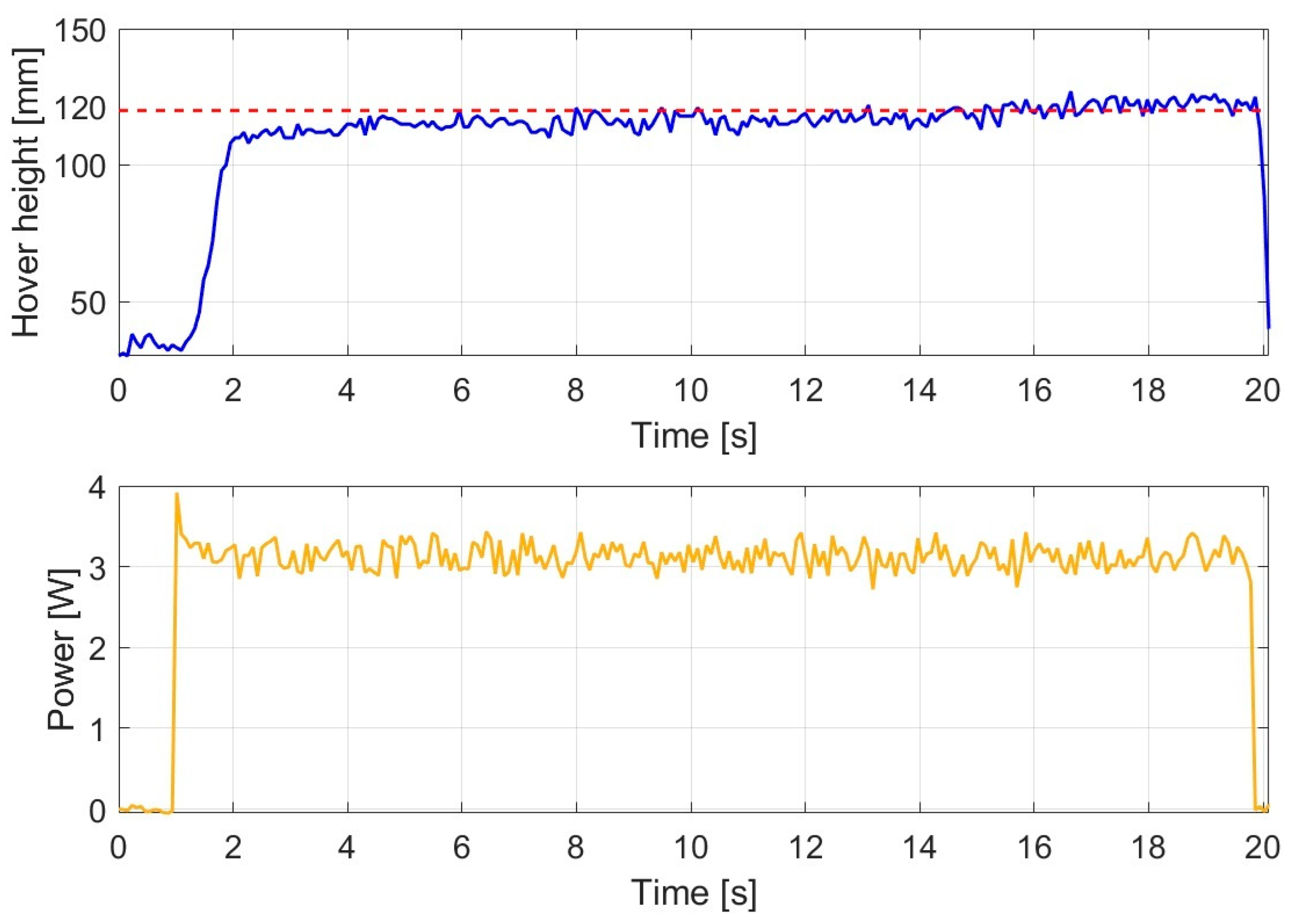

The response of the SMC controller under constant wind disturbance is illustrated in

Figure 11.

Under wind loading with a velocity of 10 km/h applied at an angle of 45°, the sliding mode controller exhibited relatively robust behavior, although stabilization occurred in a slightly under-compensated region. During wind disturbance, the average hovering altitude was 108.927 mm, which is below the desired 120 mm reference value but still represents a substantially better result than that achieved by the PID controller under the same conditions.

Based on the power profile, the average hovering power consumption of the SMC controller was 3.555 W, which is lower than that of the PID controller and corresponds to an energy saving of approximately 14%.

The magenta curve shown in the lower panel again represents the evolution of the sliding surface variable s. After the transient phase, the value of the sliding surface rapidly converged to the vicinity of zero, indicating that the system entered the sliding mode. The subsequent small-amplitude oscillations can be attributed to the continuous disturbances caused by the wind loading; however, the sliding mode was maintained throughout the experiment, confirming the robust stability of the controller.

Overall, the SMC controller performed well under strong external disturbances by providing acceptably stable hovering with moderate altitude loss and favorable energy efficiency, while the sliding mode successfully preserved dynamic stability.

The behavior of the drone controlled by the FOPID controller under constant wind disturbance is illustrated in

Figure 12.

When controlled by the FOPID approach under wind loading with a velocity of 10 km/h applied at an angle of 45°, the drone rapidly approached the vicinity of the reference following the rising phase; however, due to the persistent disturbance, the hovering altitude stabilized below the desired level. The measured average hovering altitude was 108.234 mm, indicating a significantly smaller altitude loss than that observed for the PID controller.

Based on the power response, the average energy demand during hovering was 3.294 W, corresponding to an energy saving of approximately 20% relative to the PID controller.

The results indicate that under wind loading, the FOPID controller provided an appropriate compromise between relatively stable hovering altitude and low energy consumption, although exact reference tracking was not fully achieved due to the influence of nonlinear disturbances.

The behavior of the drone controlled by the integrator-augmented LQ controller under constant wind disturbance is illustrated in

Figure 13.

Under wind loading with a velocity of 10 km/h applied at an angle of 45°, the LQI controller exhibited robust hovering performance and achieved one of the best reference tracking results among the tested methods. Despite the wind disturbance, the drone stabilized close to the reference value, with an average hovering altitude of 118.321 mm. This represents only a 1.4% deviation from the 120 mm target, indicating excellent control accuracy in the disturbed environment.

In terms of energy consumption, the system’s average power consumption during hovering was one of the lowest among the controllers, with a value of 3.190 W, resulting in a 23% energy saving compared to the PID controller.

The graph demonstrates that the LQI controller effectively handled the uncertainties caused by wind disturbance, which was facilitated by the integration of the integral term. The reference tracking remained accurate, while the hovering energy consumption was one of the most favorable among the controllers tested.

The behavior of the drone controlled by the MPC controller under constant wind disturbance is illustrated in

Figure 14.

The model predictive controller provided stable and well-damped hovering even under disturbance. The average hovering altitude was 117.162 mm, showing only a moderate deviation from the 120 mm reference value, and the controller maintained quasi-stationary behavior even in the presence of disturbance.

The average power consumption was 3.109 W, representing a 25% energy saving compared to the PID controller. The power profile showed relatively small-amplitude oscillations, which can be attributed to the fluctuating aerodynamic resistance caused by the wind; however, the MPC controller effectively handled these changes, and motor control did not require excessive compensation.

Based on the presented results, the MPC controller provided balanced altitude holding and low energy consumption, even under wind disturbance.

The response of the H∞ controller under constant wind disturbance is shown in

Figure 15.

Among the controllers tested, the H∞ controller delivered one of the best performances under disturbance. Despite the constant wind loading of 10 km/h at an angle of 45°, the system achieved relatively accurate altitude control, with an average hovering altitude of 112.645 mm.

The energy consumption of the H∞ controller was the lowest, with an average power consumption of 2.783 W during hovering, which represents a 33% energy saving compared to the PID controller. The power profile exhibited slight oscillations, but their amplitude remained low, indicating that the H∞ controller effectively handled the aerodynamic disturbances caused by the wind.

Based on the measured results, the H∞ controller demonstrated robust performance, good disturbance rejection, and low-energy operation.

3.3. Robustness Analysis Under Sudden Load Variation

In order to investigate robustness properties, the altitude-holding behavior of the controllers was also evaluated in the presence of a suddenly occurring external disturbance. The objective of the investigations was to analyze the extent to which the individual control methods are capable of maintaining the desired hovering altitude and ensuring stable operation while handling deviations induced by the disturbance, using unchanged controller parameters. During the experiments, the drone was operated under identical initial conditions in all cases. Following controller activation, the system reached the 120 mm reference altitude, and after the establishment of a steady hovering state, an external disturbance was applied. The disturbance was realized using a body with a mass of 4 g, corresponding to approximately 10.8% of the total mass of the drone. The body was movable along the vertical guiding structure of the experimental setup and was applied from a height of 25 cm in each measurement to generate the disturbance acting on the drone.

The applied disturbance method affected the vertical dynamics of the system, thereby inducing a sudden load variation during the altitude control task. This condition represented a challenge equivalent to model parameter uncertainty combined with an external disturbance for the controllers, making it suitable for the comparative investigation of robustness properties.

During the robustness investigations, the evaluation focused exclusively on the evolution of the altitude response, the magnitude of the deviation induced by the disturbance, and the characteristics of the return to the hovering state. The measurements were conducted for all investigated controllers under identical experimental environments and measurement conditions, ensuring objective comparability of the results.

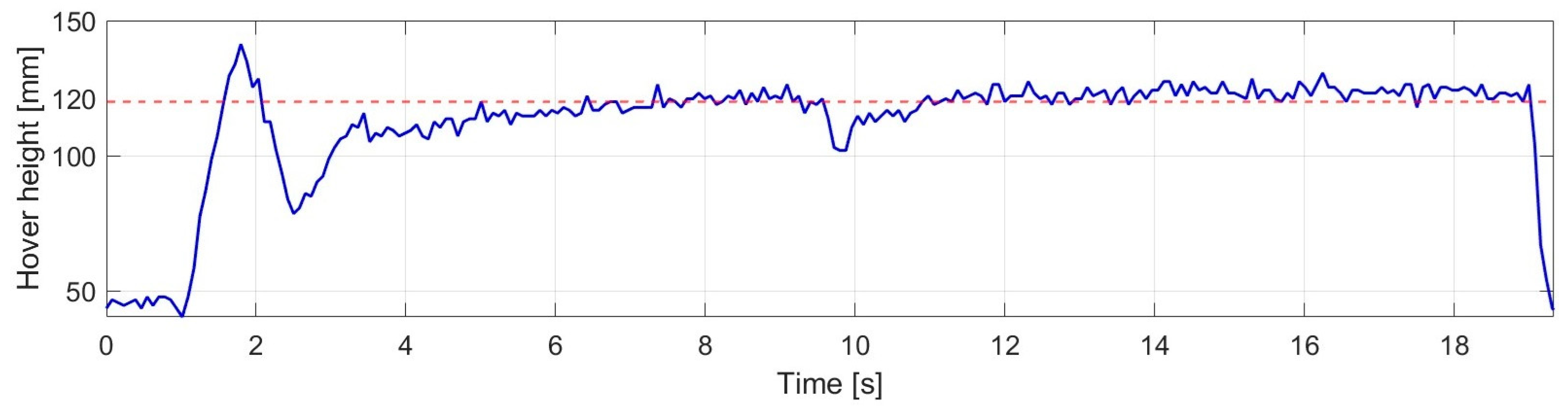

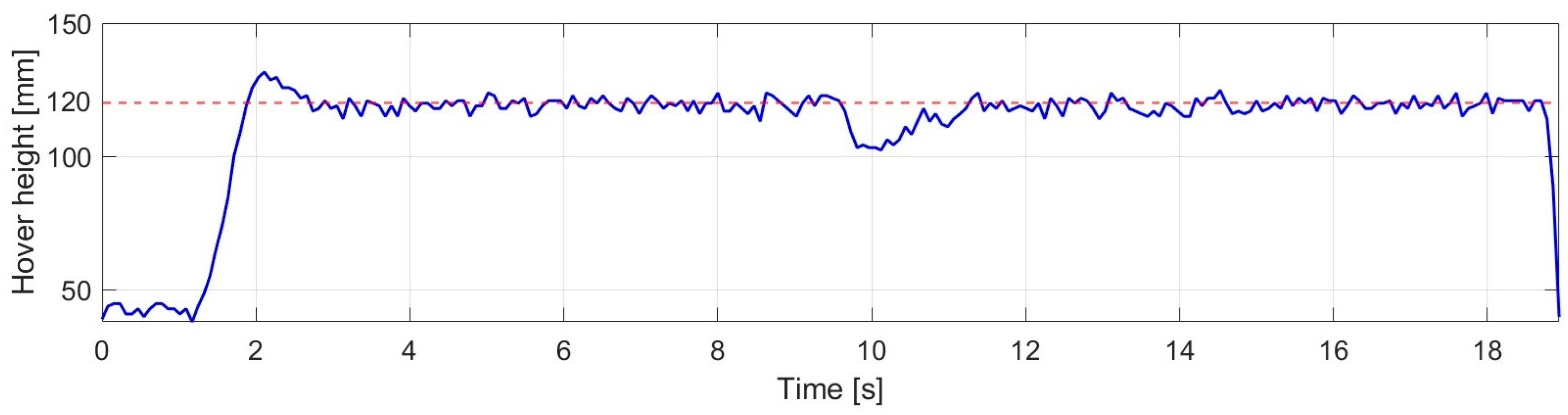

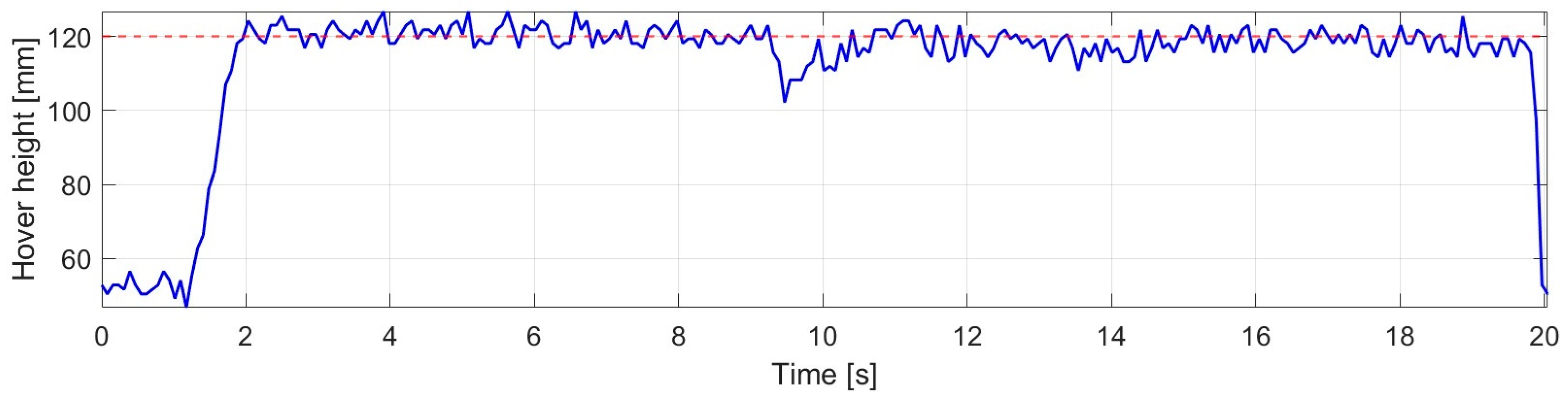

The robustness behavior of the PID controller under sudden load variation is presented in

Figure 16.

After the reference value was reached and the hovering state was established, an external disturbance was applied at 9.562 s, which resulted in a clearly identifiable transient deviation in the altitude response. As a consequence of the disturbance, the altitude decreased to a minimum value of 101.947 mm, indicating a significant but short-duration deviation relative to the reference value.

Following the removal of the disturbance, the system was stably driven back into the desired operating range under PID control, and steady-state behavior was re-established within 1.178 s. During the post-disturbance hovering phase, the average altitude was obtained as 123.289 mm, indicating a small residual steady-state deviation around the reference. Based on

Figure 16, it can further be observed that no persistent instability or growing oscillation occurred after the disturbance; therefore, the PID controller fulfilled the altitude-holding task in a fundamentally robust manner under the investigated load variation.

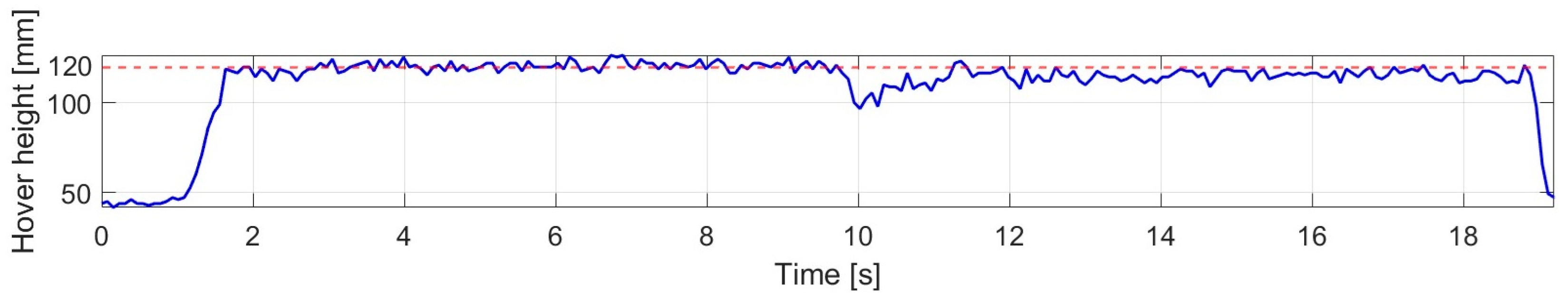

The robustness behavior of the backstepping controller under sudden load variation is presented in

Figure 17.

After the steady hovering state was achieved, an external disturbance was applied at 9.573 s, resulting in an immediate but limited deviation in the altitude response. As a consequence of the disturbance, the altitude decreased to a minimum value of 102.375 mm. Following the removal of the disturbance, the system was rapidly and stably driven back into the steady operating range under backstepping control. The new equilibrium state was established within 1.101 s. During the post-disturbance hovering phase, the average altitude was obtained as 119.258 mm, indicating only a slight deviation relative to the reference value. Based on

Figure 17, it can be concluded that no persistent oscillation or unstable behavior developed after the disturbance; therefore, the backstepping controller exhibited robust and well-balanced altitude-holding performance under the investigated load variation.

The robustness behavior of the SMC under sudden load variation is presented in

Figure 18.

After the establishment of the steady hovering state, an external disturbance was applied at 9.712 s, resulting in a pronounced but well-defined deviation in the altitude response. As a consequence of the disturbance, the altitude decreased to a minimum value of 96.827 mm, which indicates one of the largest instantaneous deviations from the reference value among the investigated controllers.

Following the removal of the disturbance, the system was stably driven back into the steady operating range under SMC control. The new equilibrium state was established within 1.174 s, which is of a similar order of magnitude in terms of recovery time compared to the PID and backstepping controllers. During the post-disturbance hovering phase, the average altitude was obtained as 115.498 mm, indicating a moderate but persistent deviation relative to the reference value.

Based on

Figure 18, it can be concluded that, despite the significant load variation, the sliding mode controller was capable of maintaining stable system operation; however, the amplitude of the initial response to the disturbance and the post-disturbance steady-state deviation were larger than those observed for the PID and backstepping controllers.

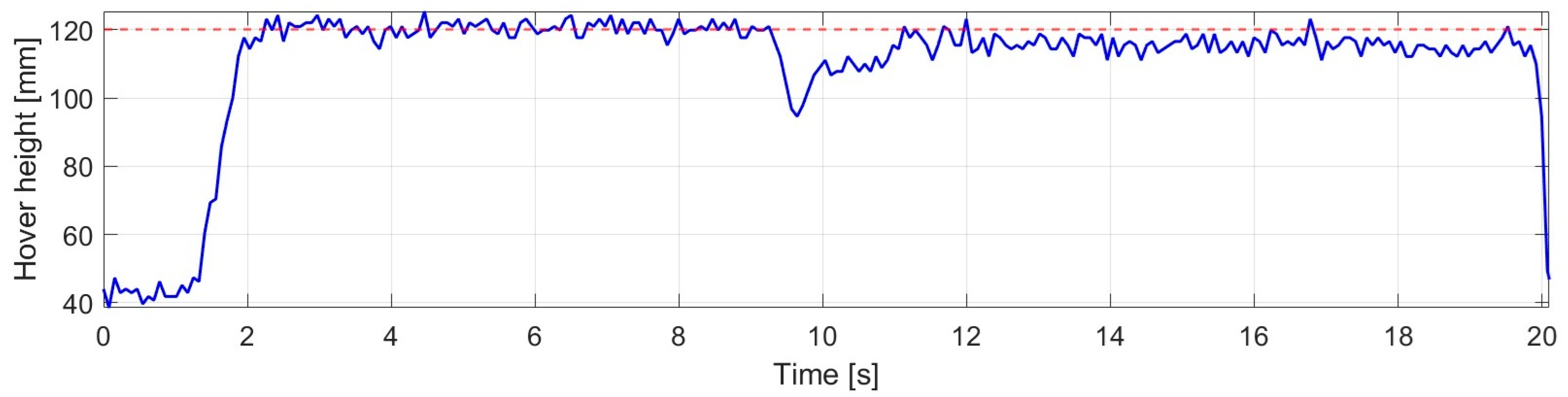

The robustness behavior of the FOPID controller under sudden load variation is presented in

Figure 19.

After the establishment of the steady hovering state, an external disturbance was applied at 9.253 s. As a result of the disturbance, the altitude decreased to 94.600 mm, which represents one of the largest instantaneous altitude deviations relative to the reference value among the investigated controllers.

Following the removal of the disturbance, the system was stably driven back into the steady operating range under FOPID control. The new equilibrium state was established within 1.490 s, which indicates a longer recovery time compared to the classical PID, backstepping, and SMC controllers. During the post-disturbance hovering phase, the average altitude was obtained as 115.867 mm.

It can be concluded that, despite the significant load variation, the FOPID controller—similarly to the previously discussed controllers—was capable of maintaining stable system operation.

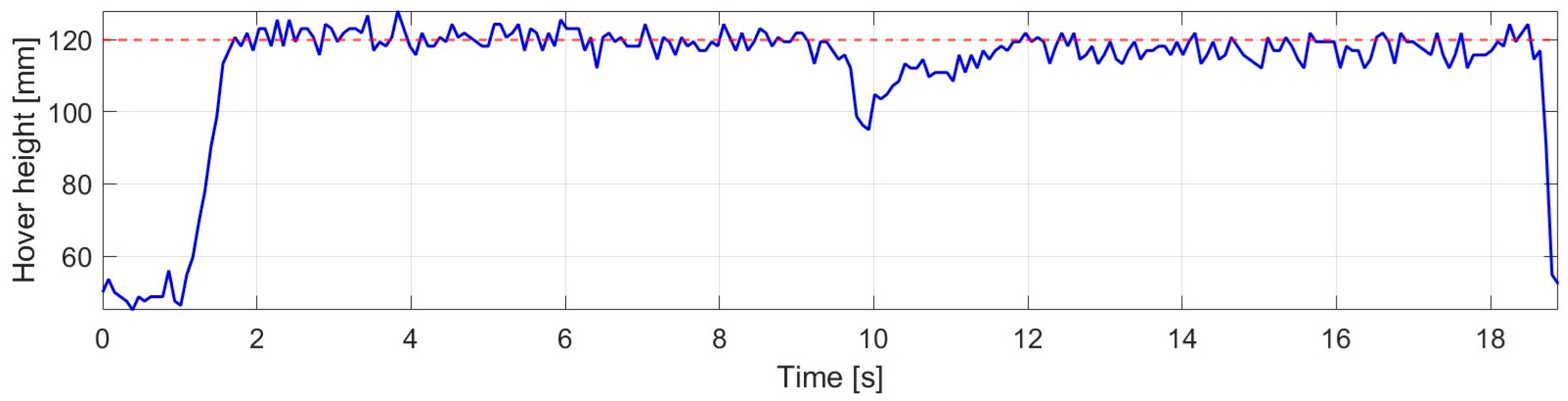

The robustness behavior of the LQI controller under sudden load variation is presented in

Figure 20.

After the establishment of a hovering state in the vicinity of the reference, the disturbance occurred at 11.835 s, causing a clearly identifiable transient deviation in the altitude response. As a result of the disturbance, the altitude decreased to a minimum value of 103 mm, which can be considered a moderate deviation compared to the other investigated controllers.

Following the deviation induced by the load variation, the system gradually returned to the stable operating range under LQI control. The time required for the establishment of the new equilibrium state was 1.73 s, indicating a slower recovery dynamic compared to the classical PID and backstepping controllers. However, during the post-disturbance hovering phase, the average altitude was obtained as 120.238 mm, which is practically identical to the reference value; therefore, the steady-state deviation can be considered negligible.

It can be concluded that the state-space-based control augmented with an integral term effectively compensated for the persistent effects arising from the load variation, while no unstable behavior or significant oscillation developed during the recovery process.

The robustness behavior of the model predictive controller under sudden load variation is presented in

Figure 21.

After the establishment of the steady hovering state, the disturbance occurred at 9.622 s, causing a significant transient deviation in the altitude response. As a result of the disturbance, the altitude decreased to a minimum value of 95.019 mm.

Following the cessation of the load variation, the system was stably returned to the steady operating range under MPC control. The recovery process was completed within 2.188 s, which represents the longest adaptation time among the investigated controllers. During the post-disturbance hovering phase, the average altitude was obtained as 117.528 mm, indicating a moderate steady-state deviation relative to the reference value.

Despite the significant load variation, the MPC was capable of maintaining stable system operation; however, the response to the disturbance exhibited slower dynamics compared to the conventional and robust controllers.

The robustness behavior of the H∞ controller under sudden load variation is presented in

Figure 22.

During the steady hovering state, the disturbance occurred at 9.232 s. As a result of the disturbance, the altitude decreased to a minimum value of 102.090 mm, which can be considered a moderate deviation relative to the reference value.

Following the load variation, the system was stably returned to the steady operating range under H∞ control. The recovery process was completed within 1.407 s, indicating balanced dynamic behavior. During the post-disturbance hovering phase, the average altitude was obtained as 118.414 mm, indicating a small steady-state deviation relative to the reference value.

The H∞ controller effectively handled the suddenly occurring load variation, while the altitude response did not exhibit unstable or oscillatory behavior.

3.4. Analysis of Computational Complexity and Real-Time Feasibility

In order to evaluate the applicability of the investigated controllers in real-time, embedded UAV applications, an experimental analysis of computational complexity was also carried out. The HIL environment enabled not only the objective assessment of control performance but also the measurement of time-related characteristics associated with controller execution. The evaluation of computational performance was based on three main metrics: round-trip latency, average controller computation time, and maximum controller computation time.

Round-trip latency denotes the total elapsed time between the transmission of the control signal computed in the MATLAB environment and the reception of the measurement data returned by the Arduino microcontroller. This metric includes the duration of serial communication, data processing, and the execution cycle on the microcontroller; therefore, it represents the overall latency of the complete HIL control loop.

The controller computation time refers exclusively to the execution time of the control algorithm on the MATLAB side, which is directly related to the mathematical complexity of the controller. The average value was obtained as the mean of the computation times measured over an extended hovering interval, while the maximum value represents the largest single computation time observed.

A summary of the measured results is provided in

Table 3.

Based on the measured results, it can be concluded that the computational demand of the classical PID, LQI, SMC, and backstepping controllers is negligible relative to the 20 Hz sampling period (50 ms). For these controllers, the average computation time was typically on the order of 0.002–0.003 ms, while the maximum values also remained several orders of magnitude below the sampling period. This clearly demonstrates the real-time feasibility of these methods, even when implemented on microcontrollers with limited computational capacity.

In the case of the FOPID and H∞ controllers, a slight increase in computation time was observed, which can be attributed to the numerical approximation of fractional-order operators and to the robust state-space-based structure, respectively. Nevertheless, their maximum computation times remained below 0.05 ms, which still provides a substantial time margin for real-time execution.

For the MPC controller, the computational demand was higher. The average computation time was 0.5923 ms, while the maximum value reached 1.3408 ms, resulting from the online optimization task and the matrix operations performed over the prediction horizon. Despite this, these values remained well below the sampling period; therefore, within the investigated HIL environment, the MPC controller was executed stably and without interruption.

The round-trip latency times were found to lie within a nearly identical range for all controllers (≈27–28 ms), indicating that the overall control-loop delay is primarily determined by communication and microcontroller-side processes rather than by the computation time of the control algorithms.

Overall, it can be concluded that the investigated controllers—including modern methods based on optimization and robust design—can be executed in real time in a stable and reliable manner within the present experimental setup. The analysis of computational complexity supports the conclusion that modern controllers providing improved energy efficiency and robustness do not necessarily entail a computational overhead that would hinder their practical implementation in embedded UAV applications.

4. Summary of Results

This section provides a summary of the experimental results obtained under disturbance-free conditions and under wind loading. Controller performance is evaluated according to a unified set of criteria, including hovering accuracy, stabilization dynamics, and energy consumption. The purpose of this summary is to provide an overview of how the individual controllers behaved under different operating conditions and to what extent they contributed to stable and energy-efficient altitude regulation.

The measurements for each investigated controller were carried out through ten repeated experiments under identical experimental conditions, both in disturbance-free and wind-loaded environments. During the statistical evaluation, basic dispersion-based metrics were determined. Under disturbance-free conditions, the largest relative standard deviation was observed for power consumption at 5.16% (±0.13 W), while for altitude holding a value of 2.52% (±2.95 mm) was observed. In the presence of wind loading, these values increased to 7.6% (±0.18 W) and 6.25% (±6.26 mm), respectively. Throughout the investigations, the measured dispersion values for all controllers remained within these ranges, which confirms the good repeatability and reliability of the results.

4.1. Summary of Results Based on Disturbance-Free Tests

Table 4 summarizes the hovering performance of the investigated controllers under disturbance-free operating conditions based on several criteria, including average hovering altitude, average power consumption, settling time, initial power peak, and overshoot.

In terms of hovering accuracy, the PID, FOPID, LQI, and H∞ controllers achieved average altitudes closest to the reference value, within the range of 119.693–120.793 mm. However, the PID controller exhibited a significant overshoot of 158 mm, indicating undesirable transient behavior. In contrast, the LQI (119.891 mm) and FOPID (119.880 mm) controllers achieved comparable accuracy without overshoot, resulting in more stable and controlled rising behavior.

With respect to energy consumption, the H∞ controller proved to be the most efficient, exhibiting the lowest average power consumption of 2.452 W. This was followed by the LQI controller (2.632 W) and the FOPID controller (2.754 W), both of which also demonstrated favorable energy efficiency. The highest power demand was observed for the PID controller (3.584 W), which can be attributed to overshoot and large-amplitude corrective actions during the transient phase. Relative to the average power consumption of the PID controller, the backstepping controller achieved approximately 16% lower energy usage, the SMC controller about 21%, the FOPID controller 23%, the MPC controller 22%, and the integrator-augmented LQ controller nearly 27% lower average power consumption. The largest energy saving was observed for the H∞ controller, which required approximately 32% less average power than the PID controller. These results clearly demonstrate that, for disturbance-free hovering tasks, several of the investigated modern control strategies offer significant energy-efficiency advantages over classical PID control, which can directly contribute to increased flight endurance and reduced battery loading.

Based on settling time, the SMC and FOPID controllers achieved the best performance (1.953 s and 1.950 s, respectively), while the PID controller exhibited significantly slower convergence (4.858 s). The longest settling time was observed for the LQI controller (6.182 s), which can be explained by the slower initial response and the influence of the integral action.

When examining the initial power peak, the LQI controller achieved the lowest value (2.555 W), indicating the smallest initial load on the motor. The highest peak was produced by the PID controller (4.556 W), which is consistent with the aggressive transient behavior observed based on the other performance indicators.

Based on the results obtained under disturbance-free operating conditions, it can be concluded that the performance of the classical PID controller is inferior to that of more advanced control strategies in several aspects. Although hovering close to the reference value was achieved, the significant overshoot, the high initial power peak, and the relatively high average power demand indicate that PID control is not an optimal choice for UAV applications in which precise transient behavior and energy efficiency are of primary importance. At the same time, several controllers were identified that exhibit clear advantages over PID control.

Among the investigated methods, the H∞ controller proved to be the most energy-efficient solution while maintaining balanced hovering accuracy and transient stability, making it the most favorable alternative from an energy-efficiency perspective. Although a moderate overshoot was observed before reaching the reference altitude (130 mm), this effect can be considered negligible. The integrator-augmented LQ controller also exhibited very low energy demand, overshoot-free and accurate hovering altitude, and stable operation; however, a longer settling time was observed. The FOPID controller, applied as an enhancement of PID control, provided fast settling time, relatively low energy demand, and overshoot-free transient behavior, resulting in significantly more favorable and stable performance compared to classical PID control. The MPC controller delivered a fast and well-damped transient response and stable hovering performance with relatively low energy consumption, leading to more predictable and energy-efficient operation than PID control.

Among the nonlinear approaches, the backstepping controller ensured good damping and stable hovering, although its energy demand was higher than that of modern linear or predictive controllers. Nevertheless, it represents a reliable alternative in scenarios where explicit handling of system nonlinearities is of particular importance. In the case of the backstepping controller, an initial overshoot of 152 mm was observed before reaching the reference altitude; however, this value remains lower than the 158 mm overshoot recorded for the PID controller. The SMC approach achieved fast settling time and robust behavior; however, both its energy consumption and hovering accuracy were inferior to those of the H∞, LQI, FOPID, and MPC controllers, while still outperforming the classical PID controller.

Overall, it can be stated that several modern control strategies can be recommended as alternatives to PID control, each offering distinct advantages. If energy-efficient operation is the primary requirement, the H∞ controller provides the most favorable solution. If overshoot-free and highly accurate hovering altitude is prioritized, the LQI and FOPID controllers represent the most suitable alternatives. If fast and well-damped transient response is desired, the results obtained with the FOPID and MPC controllers appear the most promising. The aggregated results therefore indicate that PID control delivers less favorable performance in multiple aspects, and its replacement with modern control strategies is recommended to achieve more accurate hovering, lower energy demand, and improved transient behavior.

4.2. Summary of Results for the Wind-Disturbed System

Table 5 summarizes the performance of the controllers under constant wind loading with a velocity of 10 km/h applied from above at an angle of 45°. The evaluation is based on the average hovering altitude, the average power consumption, and the improvement in energy efficiency relative to the PID controller.

Wind loading caused a substantial degradation in the performance of the classical PID controller. The average hovering altitude decreased to 93.960 mm, clearly indicating the limited disturbance rejection capability of this method. The power demand of the PID controller was the highest among the investigated approaches (4.155 W), suggesting that large corrective actions were required to counteract the wind disturbance; however, these efforts were insufficient to maintain hovering close to the reference value.

Among the nonlinear methods, the backstepping controller achieved an average hovering altitude of 114.529 mm with a power consumption of 3.692 W, resulting in well-controlled hovering despite the presence of wind-induced disturbances. The SMC controller maintained an average altitude of 108.927 mm with moderate energy demand (3.555 W) for the investigated system.

Among the modern control strategies, the LQI and MPC controllers provided the best reference-holding performance. The LQI controller maintained an average altitude of 118.321 mm, while the MPC controller achieved 117.162 mm, remaining closest to the 120 mm target despite the wind loading. Their energy consumption also remained favorable (3.190 W and 3.109 W, respectively), which is particularly advantageous in dynamically changing environments. The FOPID controller maintained an average altitude of 108.234 mm, which, although inferior to the performance of the LQI and MPC controllers, was significantly better than that of the PID controller, while its energy demand (3.294 W) can still be considered acceptable.

The H∞ controller exhibited the lowest energy consumption (2.783 W), representing an outstanding result under wind loading conditions. At the same time, the average hovering altitude decreased to 112.645 mm, indicating that the controller applied less aggressive corrective action in order to prioritize robustness and energy efficiency. Such behavior is advantageous in applications where energy saving is the primary objective and a moderate deviation from the reference altitude can be tolerated.

In summary, the classical PID controller exhibited significant performance degradation under wind loading in terms of both accuracy and energy demand. In contrast, several modern controllers demonstrated suitability as replacements for PID control in turbulent environments. The most accurate reference tracking under wind disturbance was achieved by the LQI and MPC controllers, while the best energy efficiency was provided by the H∞ controller. Accordingly, the application of advanced control strategies instead of PID control is recommended, as they provide significantly more stable, reliable, and energy-efficient operation in environments affected by wind disturbances.

4.3. Summary of the Robustness Analysis Results

The results obtained during the robustness analysis are summarized in

Table 6.

Based on the summarized results of the robustness investigations, it can be concluded that the investigated controllers responded differently to the sudden load variation, both in terms of the magnitude of the altitude deviation and the recovery dynamics. In the case of the backstepping and PID controllers, the recovery times were among the shortest. The H∞ controller exhibited balanced robustness properties, as both the minimum altitude deviation and the recovery time assumed moderate values, while stable steady-state operation was maintained. For the LQI controller, the recovery process was slower; however, the post-disturbance average altitude was practically identical to the reference value, which confirms the effective static error compensation provided by the integral structure.

For the SMC and FOPID controllers, larger instantaneous altitude deviations were observed, whereas the MPC controller exhibited the longest recovery time, which can be explained by the computational and dynamic characteristics of the predictive optimization mechanism. Nevertheless, all investigated controllers were capable of maintaining stable system operation despite the applied load variation.

Overall, the results confirm that the investigated control methods offer different trade-offs between robustness, transient behavior, and steady-state accuracy, which should be carefully considered depending on the specific application requirements.

4.4. Comparative IAE- and MAE-Based Analysis in a Disturbance-Free Environment

For the quantitative evaluation of the global behavior of the controllers over the entire flight duration, the IAE (Integral of Absolute Error) and MAE (Mean Absolute Error) performance metrics were applied. The analysis covered the complete measurement interval; therefore, the initial transient, the settling phase, and the steady hovering state were all taken into account. This evaluation approach complements the earlier comparison based exclusively on average values calculated during the steady hovering phase.

The IAE and MAE values computed during the experiments conducted in a disturbance-free environment are summarized in

Table 7.

Based on the results, it can be concluded that the H∞ controller achieved the lowest IAE and MAE values, indicating the smallest overall altitude deviation when evaluated over the entire flight duration. Similarly favorable performance was observed for the MPC and FOPID controllers, which also exhibited low global error metrics, primarily due to their faster transient behavior.

In contrast, higher IAE and MAE values were obtained for the LQI and SMC controllers, which can be attributed mainly to longer settling times and larger deviations occurring during the initial transient phase. This observation is consistent with the previously discussed results related to the hovering phase, where the LQI controller provided good steady-state accuracy but was characterized by slower dynamic response.

In order to provide a quantitative evaluation of controller robustness, the integral of the absolute error (IAE) and the mean absolute error (MAE) were also determined for the experiments conducted under wind loading, considering the entire investigated time interval. The resulting metrics enable a comparable assessment of the investigated methods with respect to their sensitivity to external aerodynamic disturbances.

The IAE and MAE values obtained under wind disturbance conditions are summarized in

Table 8.

Based on the data presented in

Table 8, it can be concluded that, in the case of the PID controller, wind disturbance resulted in a significant accumulation of error, which is clearly reflected by the magnitude of the IAE and MAE values. This indicates that the classical PID structure exhibits limited robustness against unmodeled external disturbances in the present application environment.

The backstepping and LQI controllers exhibited substantially lower error values, which can be attributed to their model-based structure and to the favorable disturbance rejection properties of the integral and backstepping-based formulations. These methods provided moderate average deviations from the reference value even in the presence of wind loading.

The MPC controller achieved the lowest IAE and MAE values under wind disturbance conditions, indicating effective disturbance handling capability resulting from its predictive nature and optimization-based decision-making process. However, these advantages are accompanied by the increased computational complexity discussed previously, which represents a trade-off that must be considered in embedded system implementations.

The SMC and FOPID controllers demonstrated intermediate performance based on the evaluated error metrics.

Overall, the IAE and MAE results obtained under wind disturbance conditions confirm that more advanced, model-based, and optimization-driven control approaches enable more effective error reduction in the presence of external aerodynamic disturbances, while simpler controllers exhibit more limited robustness.

4.5. Controller Selection Guidelines Through the Association of Design Characteristics and Measured Performance Differences

In order to support the interpretation of the differences among the investigated controllers and to facilitate practical applicability, the measured results are discussed not solely as a ranking, but in relation to the structural and design characteristics of the controllers. The objective of the presented comparison is to illustrate that different control principles—classical feedback control (PID), fractional-order extension (FOPID), integral state-feedback control (LQI), optimization-based predictive control (MPC), robust state-space design (H∞), and nonlinear methods (SMC, backstepping)—lead to different trade-offs with respect to accuracy, transient dynamics, disturbance sensitivity, and computational demand.

The hover altitude, energy, and transient performance metrics measured in a disturbance-free environment (

Table 4), the performance under wind loading (

Table 5), the characteristics of the robustness analysis (

Table 6), as well as the global error metrics computed over the entire flight interval (

Table 7 and

Table 8) jointly enabled an evaluation of the controllers that addresses not only the question of “which performs better,” but also which method can be regarded as an appropriate choice for a given application objective. Real-time feasibility was supported by the round-trip latency measured in the HIL environment and by the controller computation times on the MATLAB side (

Table 3).

In the case of the classical PID structure, reference tracking was ensured during disturbance-free hovering (

Table 4); however, significant overshoot and a large initial power peak were observed, which, together with the higher average energy demand, indicate more aggressive transient behavior. Under wind loading, the hovering altitude decreased considerably (

Table 5), and the order-of-magnitude increase in the IAE/MAE values computed over the entire time interval (

Table 8) indicates that disturbance rejection capability was limited in this configuration. This behavior can be consistently interpreted by noting that the PID controller—without model-based prediction and explicit robust design objectives—performs corrections primarily based on the feedback error signal; therefore, under sustained aerodynamic disturbances, the required operating-point shift and compensation can be achieved only to a limited extent.

In the case of the FOPID controller, the numerical approximation of the fractional-order integral and derivative terms enabled the control action to respond not only to the instantaneous error but also sensitively to the past evolution of the error, which resulted in favorable transient behavior and global error metrics in a disturbance-free environment (

Table 4 and

Table 7). Under wind loading, however, the global error metrics were less favorable compared to those of the LQI and MPC controllers (

Table 8), indicating that the smoother correction provided by the fractional terms is not always sufficient to compensate for sustained external aerodynamic disturbances.

For the LQI controller, the explicit inclusion of an integral state allowed more effective compensation of static error, which was reflected in the robustness analysis by the post-disturbance average altitude remaining close to the reference value (

Table 6). At the same time, a longer settling time was observed in a disturbance-free environment (

Table 4), and the global IAE/MAE values were less favorable compared to the best-performing methods (

Table 7), which can be explained by the error accumulated during the slower rise phase. This behavior typically arises from the trade-off between the integral term and the weighting matrices (Q and R), as stable, overshoot-free operation and static error reduction are often achieved at the expense of slower transient response.

In the case of the MPC controller, the predictive nature and optimization-based decision-making resulted in favorable IAE/MAE values over the entire time interval (

Table 7 and

Table 8), particularly under wind loading, where the lowest global error metrics were obtained (

Table 8). In the robustness analysis, however, a longer recovery time was observed (

Table 6), which can be consistently interpreted by noting that predictive optimization, while accounting for constraints and weightings, often selects less aggressive corrections for the short-term compensation of sudden disturbances. The computational complexity was significantly higher compared to the other methods (

Table 3); nevertheless, even the maximum computation time remained well within the sampling period with ample margin, such that stable real-time execution was achieved in the investigated HIL environment.

For the H∞ controller, the robust design philosophy and state-space-based structure resulted in balanced disturbance tolerance in the robustness analysis (

Table 6), while the lowest global error metrics were measured in a disturbance-free environment (

Table 7). Under wind loading, however, the global error metrics were not the most favorable (

Table 8), while the average energy demand remained remarkably low (

Table 5). This behavior indicates a more conservative correction strategy, in which energy efficiency and stable, robust operation are prioritized at the expense of minimal deviation from the reference value.

Among the nonlinear methods, the backstepping and SMC controllers exhibited fast recovery and maintenance of stability in the robustness analysis (

Table 6), which can be interpreted based on their structural characteristics, namely strong error enforcement through the sliding surface in SMC and the stabilizing recursive steps inherent to backstepping. At the same time, the global IAE/MAE metrics were not always the most favorable (

Table 7 and

Table 8), suggesting that, over the full duration encompassing transient, hovering, and shutdown phases, larger deviations may have accumulated in other segments despite the rapid disturbance response.

Based on the measured results, rather than identifying a single “best controller,” it can be considered more appropriate to select the controller according to the specific application objective, as the different methods provide different trade-offs:

When maximum energy efficiency and reduced actuator loading are prioritized, the application of the H∞ method can be considered justified, particularly when a moderate deviation from the reference value is acceptable (

Table 4 and

Table 8). In a disturbance-free environment, favorable global error metrics were also observed (

Table 7), supporting a balanced choice in terms of the energy–accuracy trade-off.

When reference-tracking accuracy under strong external disturbances is a primary requirement, the application of the MPC and LQI methods can be justified, since under wind loading both the average hovering altitude and the global error metrics exhibited favorable behavior (

Table 5 and

Table 8). The advantages of MPC are, however, accompanied by higher computational demand (

Table 3), which must be considered when embedded target hardware is used.

When fast, well-damped transient response and overshoot minimization are emphasized, the application of the FOPID and, in certain cases, the MPC controller can be regarded as advantageous (

Table 4 and

Table 7), as the rapid settling and favorable global error metrics support a shortened transient phase.

When stability maintenance and rapid recovery under sudden load variations are prioritized, the backstepping controller—and partly the PID controller—exhibited short recovery times (

Table 6). For such applications, however, due to the limited disturbance rejection of the PID controller under wind loading, this method can be considered suitable only in disturbance-free or mildly disturbed environments (

Table 5 and

Table 8).

For embedded systems with limited computational capacity, the computational demand of the PID, LQI, SMC, and backstepping methods can be regarded as negligible relative to the sampling period, based on the HIL measurements (

Table 3). In contrast, the computational demand of MPC was higher; nevertheless, real-time executability was still achieved in the investigated environment.

Based on the combined interpretation of the experimental results and the design characteristics of the controllers, it can be concluded that the measured performance differences arise primarily from the structural properties of the controllers. Classical error feedback, integral error compensation, predictive optimization, and robust state-space design address transient error, the effects of sustained disturbances, and the aggressiveness of the control input in fundamentally different ways. Consequently, practical controller selection should be application-dependent and should be performed along the trade-off between accuracy, energy consumption, robustness, and computational demand, based on the performance metrics summarized in the presented tables.

6. Discussion

The quantitative comparison of the experimental results presented in this study with results available in the literature enables the scientific contextualization of the research outcomes and their evaluation relative to related works.

Okasha et al. [

57] conducted experiments on a Parrot Mambo mini drone platform using PID, LQR, and MPC controllers, where altitude-holding performance was evaluated based on the norms of the vertical tracking error, takeoff overshoot, and real-time altitude deviation. In [

57], for the PID controller, the simulated Z-direction error 2-norm was reported as 21.895, accompanied by significant overshoot exceeding 50% during takeoff and by an increasing real-time altitude deviation on the order of approximately 20 cm. These findings are in good agreement with the results obtained in the disturbance-free experiments of the present study, where large overshoot was measured (158 mm,

Table 4), together with a longer settling time (4.858 s) and higher global error metrics (IAE = 259.677 mm·s, MAE = 12.023 mm,

Table 7). In the presence of wind loading, the performance of the PID controller further deteriorated, as confirmed by the substantially increased IAE (641.482 mm·s) and MAE (32.108 mm) values (

Table 8).

In the study of Okasha et al. [

57], the MPC controller exhibited overshoot-free takeoff behavior and resulted in significantly lower tracking error (Z-error 2-norm: 6.047). The results of the present study confirm this observation, as under disturbance-free conditions the MPC controller operated with a short settling time (2.110 s), a moderate initial power peak (3.273 W), and low global error metrics (IAE = 189.744 mm·s, MAE = 9.363 mm). Under wind loading, the MPC controller achieved one of the lowest IAE and MAE values (249.638 mm·s and 12.230 mm, respectively), while the average hovering altitude remained close to the reference value (117.162 mm,

Table 5). These results quantitatively confirm the advantage of MPC over PID not only in terms of transient behavior, but also with respect to the error integrated over the entire flight cycle.

The results of the present study can also be compared with the authors’ previous experimental work investigating MPC and PID controllers [

25]; however, it is important to emphasize the structural differences between the two investigations. In the earlier study, a single-degree-of-freedom mini drone test platform was applied that was equipped with an ultrasonic distance sensor, different types of motors, and a custom mechanical frame constructed from a medical spatula [

25]. In contrast, in the present work a test platform was developed based on a commercially available mini drone frame, incorporating a laser distance sensor and a different motor–actuator configuration. Nevertheless, both experimental systems represented mini UAV platforms belonging to a similar mass category, which enables qualitative and quantitative comparison of the behavior of the control methods under dynamic loads of the same order of magnitude.

In the previous work, the MPC controller demonstrated an energy efficiency improvement of approximately 20% compared to the PID controller, while hovering stability and altitude-holding accuracy were also found to be more favorable. The results of the present study confirm this observation, as the MPC controller achieved an approximately 20–25% reduction in power consumption relative to the classical PID controller in both disturbance-free and wind-loaded environments, while reference altitude tracking remained more accurate and more balanced. The consistent results observed on mini drone platforms with different sensors, actuators, and mechanical configurations, yet similar mass, indicate that the energy efficiency advantages of MPC are not tied to the specific characteristics of a particular construction. Instead, these advantages may be of more general validity for altitude control tasks of mini UAV systems, provided that the dynamic parameters of the systems are of comparable magnitude.

Rosmadi et al. [

20] experimentally investigated the performance of PID and fractional-order PID controllers on a Tello EDU quadrotor under propeller disturbance conditions. Based on their results, the FOPID controller yielded significantly smoother and more stable transient behavior, whereas pronounced oscillations and instability were observed in the case of the classical PID controller. According to the reported test results, the application of FOPID substantially reduced execution time in several cases; for example, in some experiments the test duration was reduced from 121.8 s to 81 s, corresponding to an improvement of approximately 33%. In contrast, the present study evaluates the effect of the FOPID controller in an altitude-holding task under external aerodynamic disturbances, based on quantitative error metrics and transient characteristics. During disturbance-free experiments, the FOPID controller reduced the settling time from 4.86 s to 1.95 s compared to the PID controller, representing an improvement of nearly 60%. Based on these results, it can be concluded that the advantages of the FOPID controller consistently manifest under both actuator-related disturbances and external aerodynamic disturbances.

The authors’ previous study comparing PID and H∞ controllers [

24] analyzed an altitude-holding task; however, the two investigations employed different mechanical constructions, actuation solutions, and experimental environments, and the earlier work also included explicit simulation studies in addition to practical measurements. Based on the simulation results, it was consistently demonstrated in both studies that, compared to PID control, the H∞ controller provides lower power peaks, faster noise attenuation, and lower average energy demand. This behavior manifested as approximately 19% energy savings in the earlier study and as 33% energy savings in the present investigation under disturbance-free conditions. With respect to the experimental measurements, a similar trend was also observed: in both constructions, the H∞ controller resulted in reduced overshoot, more stable hovering, and significantly lower average power consumption compared to the PID controller. However, the broader set of controllers investigated in the present article (LQI, MPC, FOPID, SMC) also enabled the identification of the fact that, under wind disturbance conditions, the H∞ controller primarily provided advantages in terms of energy efficiency, whereas the LQI and MPC controllers achieved more favorable performance in reference-tracking accuracy. Overall, it can be concluded that the two studies provide mutually reinforcing results, and that the robust and energy-efficient behavior of the H∞ controller can be confirmed independently of the specific system construction.

Saibi et al. [

58] investigated the application of the backstepping controller for a UAV altitude control task in a simulation environment. Based on the reported results, the drone reached the target altitude of 15 m in approximately 15 s, and no significant static error was observed in steady state according to the simulation plots. In the disturbance-free experiments of the present study, the average hovering altitude achieved with backstepping control was 118.346 mm for a reference value of 120 mm, indicating a small steady-state deviation; however, overshoot occurred prior to reaching the reference, with a maximum value of 152 mm. Despite this difference, both investigations support the conclusion that the backstepping method is suitable for stable altitude holding. In the present HIL-based experiments, the occurrence of overshoot during the transient phase can be interpreted as a consequence of the real hardware environment, non-ideal actuator and sensor effects, and experimental execution constraints.

In the study of Noordin et al. [

59], the SMC controller was presented exclusively in a simulation environment, where the reference altitude was set to 10 m. Based on the reported altitude trajectories, stable reference tracking was achieved both under disturbance-free conditions and in the presence of normally distributed Gaussian noise, and no noticeable altitude error was observed in the steady-state phase. From visual inspection of the rise phase, the reference altitude was reached within approximately 2 s, and no overshoot was exhibited in the altitude response.

In the present experimental investigations, the reference altitude was set to 120 mm. Under disturbance-free conditions with SMC applied, the average settled altitude was obtained as 116.556 mm, corresponding to a steady-state deviation of −3.444 mm, whereas under wind loading the average hovering altitude decreased to 108.927 mm, resulting in a deviation of −11.073 mm. The settling time under disturbance-free conditions was obtained as 1.953 s, which is consistent with the approximately 2 s rise time estimated from the figures reported by Noordin et al. [

59]. The recovery time after disturbance was 1.174 s, while the simulation results presented by Noordin et al. [

59] also indicate an approximately 2 s rise time in the presence of disturbance, suggesting fast dynamic response of the system. The overshoot measured in disturbance-free operation reached a value of 129 mm, whereas no overshoot was observed in the simulation-based SMC solution reported in the literature; therefore, the practical implementation presented in the present article exhibits differences in this respect compared to the simulation results.

The obtained experimental results can also be compared at several points with optimal control solutions augmented with an integral term reported in the literature. Godinez-Garrido et al. [

60] demonstrated stable maintenance of the reference altitude under both disturbance-free conditions and lateral wind loading using a discrete-time LQ-based controller with integral action, while achieving approximately 53% energy savings relative to PID control. In the present investigations, a similar trend was observed: the LQ controller augmented with an integrator provided average hovering altitudes close to the reference value under both disturbance-free and wind-loaded conditions, while the average power demand was reduced by approximately 27% in a disturbance-free environment and by approximately 23% under wind disturbance when compared to the PID controller.

7. Conclusions

A wide range of modern control strategies has been reported in the literature, including linear quadratic control, model predictive control, sliding mode control, backstepping methods, fractional-order PID control, and H∞ robust control. Although the theoretical advantages and simulation-based results of these approaches are well documented, the number of unified, real-time experimental investigations conducted under identical physical conditions remains limited. In particular, only a few HIL-based laboratory systems are available that enable direct comparison of multiple controllers operating on different control principles under the same experimental conditions. As a consequence, only a limited amount of practical performance data exists that can be interpreted within a common reference framework. The present study addresses this gap through the development and application of a custom single-degree-of-freedom drone test system combined with a real-time HIL environment, in which the performance of seven different altitude control methods was experimentally compared. The investigations were conducted under both disturbance-free conditions and constant wind loading with a velocity of 10 km/h applied at an angle of 45°, enabling objective evaluation of reference tracking accuracy, dynamic behavior, and energy consumption.

Under disturbance-free conditions, the classical PID controller exhibited inferior performance in several aspects, particularly with respect to overshoot and energy demand. Among the modern approaches, the H∞ controller proved to be the most energy-efficient, while the LQI and FOPID controllers ensured overshoot-free and highly accurate hovering. The MPC controller provided fast transient response and stable hovering performance with low energy consumption.

Measurements conducted under wind loading revealed that the PID controller suffered from significant performance degradation, whereas the LQI, MPC, and H∞ controllers demonstrated the highest robustness. These methods maintained hovering close to the reference value while exhibiting 23–33% lower energy demand compared to the PID controller.

Overall, the investigations confirmed that several modern control strategies can be applied more effectively than the classical PID controller for altitude regulation of mini UAVs. The H∞ controller is particularly promising due to its superior energy efficiency, while the LQI and FOPID controllers offer clear advantages in applications requiring overshoot-free and precise hovering. The MPC controller, owing to its fast response characteristics, is well suited for applications where rapid disturbance compensation is critical. The presented HIL-based experimental comparison therefore provides a significant contribution to the practical evaluation of modern altitude control methods.

When defining future research directions, a primary objective is identified as the extension of the control methods investigated in the present study to multi-degree-of-freedom drone platforms capable of full spatial motion, where, in addition to altitude control, the combined handling of lateral and rotational dynamics becomes necessary. Within this context, the integrated evaluation of the presented controllers in a realistic, multivariable UAV dynamic environment is considered justified, as it would enable a more in-depth analysis of the generalizability of the laboratory-based results.

The current experimental investigations were conducted in a controlled indoor laboratory environment, which ensured repeatability and objective comparability. In future work, it is considered appropriate to extend these investigations to outdoor conditions, where controller performance can be evaluated under airflow disturbances of varying intensity and direction, as well as under non-deterministic environmental perturbations. Such tests would allow a deeper exploration of robustness properties, with particular emphasis on long-duration stable hovering and post-disturbance recovery capabilities.

In future studies, an additional research direction may involve a more explicit treatment of energy consumption, building upon the energy-aware performance analysis applied in the present work and embedding it within an explicit optimization framework. As part of this effort, the introduction of battery models and state-of-charge-aware control objective functions may be justified, enabling the direct maximization of flight time and the adaptive optimization of energy consumption under different mission profiles.

A further research opportunity is offered by the application and comparative evaluation of the presented control methods on physically realized drone platforms with differing structural configurations and dynamic properties. In such investigations, it is advisable to maintain a unified experimental environment and consistent measurement conditions in order to ensure direct comparability of controller performance and to allow the generalizability of the results to be assessed in a reliable manner.

Finally, the applicability of the presented experimental methodology for educational and research-and-development purposes may also be subject to further investigation, particularly in the context of hardware-in-the-loop-based control engineering education and the rapid prototyping and validation of new control algorithms.