1. Introduction

Inconel 718 is a widely utilized super alloy in many critical sectors, particularly in the aerospace industry, due to its ability to maintain its hardness and strength even at elevated temperatures, as well as its resistance to creep and oxidation, and its good weldability [

1]. In the aerospace industry, Inconel 718 is frequently used in jet engine components, bolts, fasteners, and spacers within airframes [

2]. To be converted into its final product form, Inconel 718 must go through machining processes. However, due to its high wear resistance, tendency to undergo work hardening during machining, and low thermal conductivity, its machining performance is quite poor, often leading to its classification as a “difficult-to-cut” material [

3]. Conventional Machining (CM) techniques are generally inadequate for machining of Inconel 718 due to issues such as high cutting forces, poor surface quality, and high tool wear [

4]. Consequently, the machining of Inconel 718 by conventional methods falls considerably short of meeting the requirements for sustainable manufacturing.

Ultrasonic Vibration-Assisted Machining (UVAM) is a machining method that applies high-frequency and low-amplitude vibrations either to the cutting tool or workpiece [

5]. In cases where CM is inadequate, the intermittent cutting mechanism created by the ultrasonic vibrations in UVAM has yielded successful results in machining of many difficult-to-cut materials, including Inconel 718. Airao et al. [

6] compared UVAM and CM under different cooling conditions in the turning operation of Inconel 718. Their results indicated that when MQL and LCO2 were used, UVAM produced lower surface roughness and power consumption compared to CM, and generally yielded shorter and thinner chips. Suarez et al. [

7] investigated the impact of UVAM and CM on the fatigue life of Inconel 718 during milling operations. They reported that the axial vibrations generated by UVAM induced a surface hardening effect, resulting in a 14.74% increase in fatigue life. Bai et al. [

8] compared UVAM and CM in the turning operations of Inconel 718 and Inconel 625. Their findings demonstrated that UVAM produced lower cutting forces and lower surface height variation and surface roughness (Ra and Rq) values for both materials. Erturun et al. [

9] utilized UVAM in the drilling operation of Inconel 718 and reported reductions of up to 5.15% in thrust force, 30.36% in surface roughness (Ra), 22.69% in roundness error, and 33.43% in burr formation compared to conventional drilling. Yin et al. [

10] investigated the effects of ultrasonic vibration ball-end milling on the fatigue life and surface integrity of Inconel 718. Their results indicated that UVAM increased the maximum fatigue life by 2.1 times compared to CM. Additionally, they reported that UVAM improved compressive residual stress and surface microhardness. As can be seen from the literature, enhanced performance of UVAM not only improves machining efficiency but also aligns with the principles of sustainable manufacturing by reducing energy consumption, tool wear, and material waste.

While UVAM has been observed to enhance the machining performance of Inconel 718 in various machining operations, there are certain parameters that affect the performance of UVAM itself. One such parameter is the direction in which ultrasonic frequencies are applied in UVAM. Ultrasonic frequencies in UVAM can be applied in different directions, such as axial, feed or multi-axial. The application of vibrations along different axes has varying impacts on the machining performance outputs. Gao et al. [

11] developed a three-degree-of-freedom ultrasonic tool holder, and when the phase difference in vibrations along different axes was adjusted, they observed approximately a 30% reduction in cutting forces during the machining of Al7050 compared to conventional cutting processes. Rinck et al. [

12] conducted a comparative study of Longitudinal-Torsional UVAM (LTUVAM) and Longitudinal UVAM (LUVAM) in the milling of Ti-6Al-4V, finding that LTUVAM reduced cutting forces by 57%, outperforming LUVAM, which achieved a 44.3% reduction compared to CM. Pang et al. [

13] conducted a comparative study on LTUVM, single longitudinal ultrasonic vibration milling (SLUVM), and CM of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Their findings revealed that the application of LTUVM resulted in lower cutting forces compared to both SLUVM and CM, while also demonstrating superior performance in surface texturing. Lu et al. [

14] compared longitudinal–torsional ultrasonic machining (LTUM), longitudinal ultrasonic machining (LUM), and conventional drilling (CD) in the machining of CFRP-T700 composites. Their results indicated that LTUM produced lower cutting forces than both LUM and CD, attributed to the improved vibration impact characteristics and the consequent change in the material removal mechanism. Namlu et al. [

5] compared multi-axial UVAM applied in the XZ direction with variations applied solely in the X direction (X-UVAM) and solely in the Z direction (Z-UVAM) on Ti-6Al-4V material. Their findings indicated that XZ-UVAM, due to its elliptical cutting motion, resulted in lower cutting forces, surface roughness, and burr heights compared to X-UVAM and Z-UVAM. Additionally, it produced more homogeneous, uniform surfaces with fewer defects.

Garcia et al. [

15] investigated ultrasonic-assisted turning (UAT) of S235 carbon steel by means of finite element simulations, comparing the effects of one-dimensional (1D) and two-dimensional (2D) vibrations. Their results showed that 1D vibration-assisted machining (1D-VAM) operating at a vibration frequency of 30 kHz achieved up to an 18% improvement in machinability compared with conventional machining. Furthermore, when comparing 1D-VAM and 2D-VAM, lower average cutting forces and relative specific cutting energy were obtained in 1D-VAM, which was attributed to the shorter tool–material contact time. Ni et al. [

16] modeled the surface topography of microtextured surfaces generated by UVAM systems with vibrations applied in different directions and simulated the resulting surface roughness. Their findings indicated that 1D feed-direction UVAM and 2D ultrasonic elliptical vibration-assisted milling (UEVAM) in the horizontal plane produced lower surface roughness values than conventional milling. The authors emphasized that this improvement was strongly related to the direction of the applied vibration. Liang et al. [

17] applied multidirectional UVAM to SiCp/Al composites and performed a comparative study of 1D, 2D, and 3D UVAM. The results demonstrated that, regardless of vibration direction, UVAM consistently reduced cutting forces and surface roughness compared with conventional milling. However, 3D-UVAM resulted in the greatest reduction in cutting forces, whereas 2D-UVAM was most effective in reducing surface roughness, indicating that different machining outputs are influenced differently by vibration direction. Liang et al. [

18] developed a two-dimensional ultrasonic vibration-assisted grinding process for monocrystalline silicon. Compared with conventional grinding, axial ultrasonic vibration significantly improved surface quality but increased cutting forces, while vertical ultrasonic vibration achieved the greatest reduction in cutting forces at the expense of surface quality. In contrast, elliptical ultrasonic vibration simultaneously improved both cutting forces and surface quality, demonstrating that two-dimensional ultrasonic-assisted grinding provides the most balanced and effective vibration strategy. Gao et al. [

19] conducted a study combining two-dimensional ultrasonic vibration-assisted grinding (2D-UVAG) with nanofluid minimum quantity lubrication (NMQL) and revealed that ultrasonic vibrations applied in different directions produce distinct machining effects. Specifically, 1D ultrasonic vibration applied in the tangential direction resulted in lower surface roughness than axial-direction vibration. Moreover, under multi-angle 2D ultrasonic vibration, variations in the angle between vibration directions led to corresponding changes in surface roughness. These findings clearly indicate that the direction and orientation of ultrasonic vibration in 2D-UVAM play a critical role in determining machining performance.

The literature indicates that UVAM enhances machining performance for Inconel 718 compared to CM. Furthermore, it has been observed that multi-axial UVAM—where ultrasonic vibrations are applied in multiple directions—offers greater advantages than mono-axial UVAM, which applies vibrations along a single axis. In a previous study by the authors, it was reported that XZ-UVAM resulted in lower surface roughness, burr formation, and cutting forces compared to CM for Inconel 718 material [

20]. However, that earlier work was limited to a direct comparison between CM and XZ-UVAM and primarily investigated the influence of various cooling and lubrication conditions under multi-axial ultrasonic vibration. Despite these findings, the literature still lacks a systematic comparison between multi-axial UVAM and mono-axial UVAM for Inconel 718. Moreover, the individual effectiveness of ultrasonic vibrations applied along different axes in mono-axial UVAM has not yet been explored for Inconel 718, leaving a significant gap in understanding how vibration direction influences machining performance. To address these shortcomings and establish a clear contribution to the field, the novelty of the present study is defined as follows:

It provides a systematic comparison of multi-axial UVAM (XZ-UVAM) and mono-axial UVAM (X-UVAM and Z-UVAM) for Inconel 718.

It isolates and examines the effect of vibration direction in mono-axial UVAM for Inconel 718, enabling a mechanistic understanding of how vibration orientation influences machining performance.

To address the identified gaps in the literature, slot milling experiments on Inconel 718 were conducted using multi-axial (XZ-UVAM) and mono-axial (X-UVAM and Z-UVAM) UVAM. For reference, CM experiments were also performed. The machining performance was evaluated based on outputs such as cutting force, surface roughness, surface topography, surface texture, microhardness, and burr formation.

2. Materials and Methods

The Inconel 718 material used in the experiments was prepared in the form of samples with dimensions of 87 mm × 55 mm × 8 mm. The chemical composition and mechanical properties provided by the manufacturer are detailed in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively.

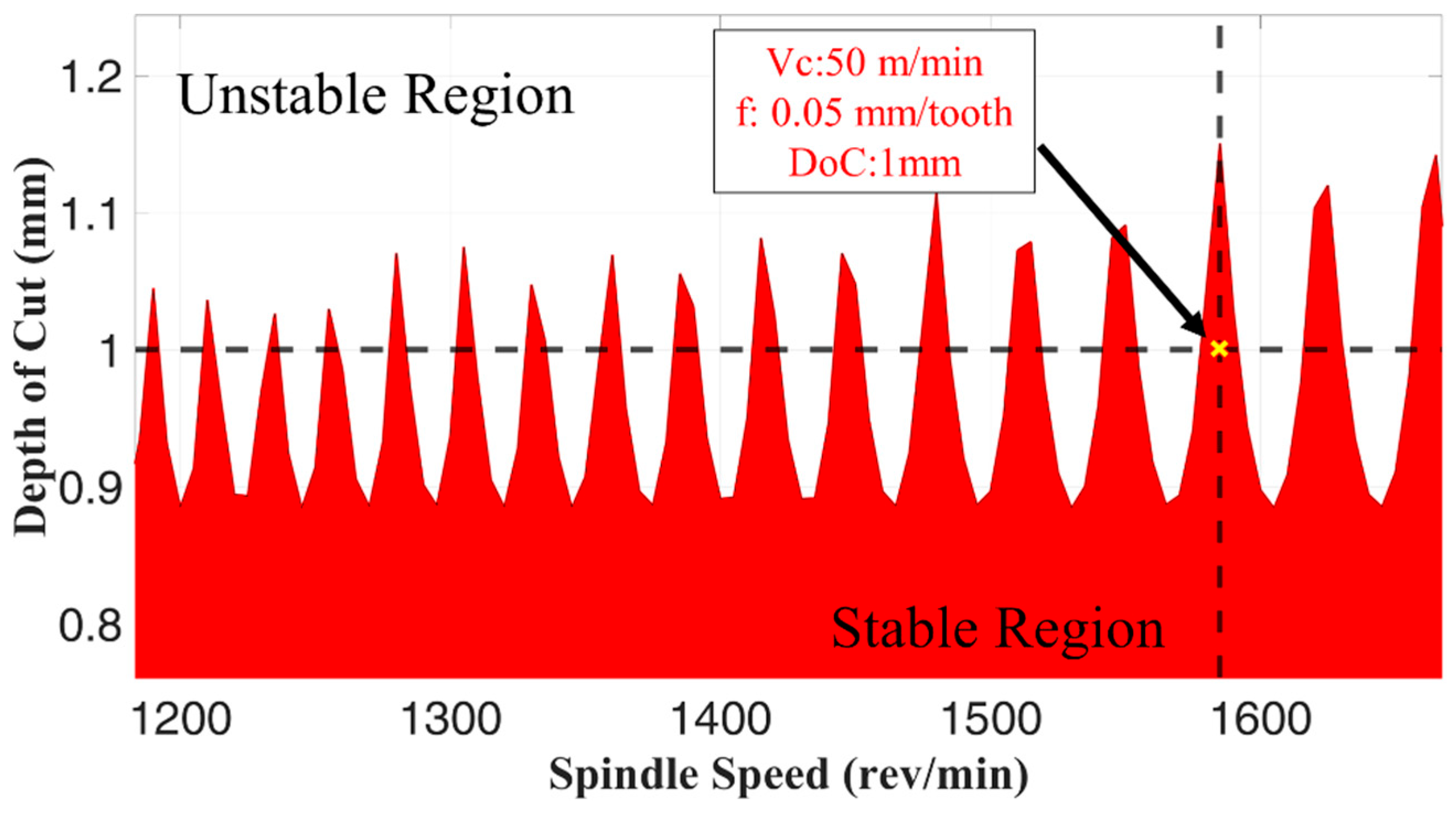

The experiments were conducted using an Akira Seiki SR3XP CNC milling center. A 10 mm diameter Iscar brand EC-A4 100-22C10-72 model TiAlN-coated four-flute solid carbide end mill was utilized in the experiments (Iscar, Tefen, Israel). Conventional flood cooling was used as cooling/lubrication technique. To ensure operation within a stable region free from chatter issues, tap testing was performed on the cutting tool, and stability lobes were identified. Consequently, machining parameters unaffected by chatter, a potential problem that can adversely impact machining performance, were established as a cutting speed of 50 m/min (around 1590 RPM), a feed rate of 0.05 mm/tooth, and a depth of cut of 1 mm. The stability lobe diagram obtained from the tap testing is shown in

Figure 1. Additionally, preliminary experiments were conducted using machining parameters selected according to the stability lobe to verify the absence of chatter. During these preliminary experiments, machining sound data were recorded and analyzed using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to identify dominant peak frequencies, a method widely established for chatter detection [

21,

22]. The FFT data revealed only the tooth passing frequency and its harmonics, thereby confirming stable zone operation during cutting. The FFT of the measured machining sound data are shown in

Figure 2.

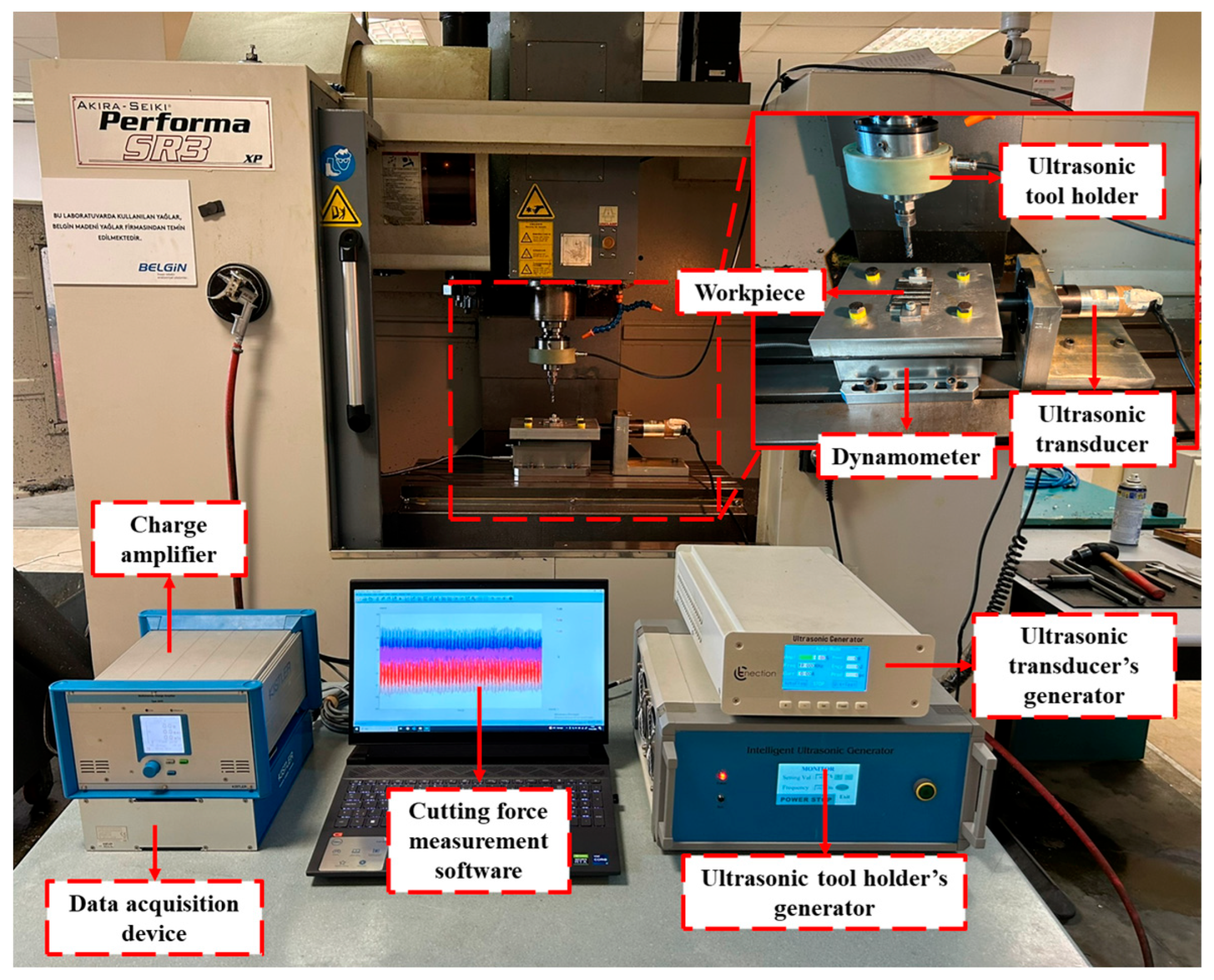

Two distinct ultrasonic systems were used to generate vibrations along different axes. The first system, operating in the axial direction (Z-UVAM), consists of an ultrasonic tool holder that applies vibrations directly to the cutting tool. The second system provides vibrations in the feed direction (X-UVAM) using a specially designed table equipped with an ultrasonic transducer, on which the workpiece is mounted. Multi-axial ultrasonic vibration machining (XZ-UVAM) was achieved by operating both systems simultaneously. Both ultrasonic systems are driven by ultrasonic generators equipped with closed-loop control. These generators automatically detect and maintain the resonant frequency of each system during operation. The amplitude is adjusted through the generator interface, and the corresponding amplitude values for each power setting are provided by the manufacturer. Based on this calibration, the amplitude for both systems was set to 6 µm. Although the amplitude was not measured externally during machining, the resonance frequency displayed on the generators consistently matched the frequencies obtained from sound measurements, confirming stable ultrasonic transmission without detectable attenuation. The ultrasonic tool holder operates at a resonance frequency of 18,100 Hz, while the ultrasonic transducer operates at 20,200 Hz. The measured frequency responses of both systems are presented in

Figure 3. The general experimental setup can be seen in

Figure 4.

The cutting forces were measured using a Kistler 9265B model dynamometer (Kistler, Winterthur, Switzerland) and Dynoware software (Version 3.3.1.0). To capture variations in cutting forces at ultrasonic frequencies, measurements were taken at a 100 kHz sampling rate. Surface roughness (Sa) and 3D surface topography measurements were conducted using the Alicona InfiniteFocus (Bruker, Graz, Austria), a non-contact 3D surface measurement device. The 3D images of the machined slots were obtained using the Alicona InfiniteFocus and analyzed with Gwyddion software (Version 2.63). To ensure repeatability, three measurements were taken from different regions of the machined slots, and the average of these measurements was considered the measured value. The surface textures were obtained from Nikon LV150N optical microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). For subsurface microhardness measurements, samples were extracted from the machined surfaces and prepared metallographically. Initially, these samples were extracted from the channels using wire EDM and then mounted in bakelite. Subsequently, the samples were ground with sandpapers of 60 to 2400 grit, polished with a 3 μm diamond solution, and etched with Kalling’s No. 2 Reagent. The subsurface microhardness was measured using a ZwickRoell ZHV10 Vickers hardness tester (ZwickRoell Group, Ulm, Germany) with a 300 g load applied for 10 s. Microhardness measurements were conducted radially at depths of 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, and 350 μm below the surface and calculated using testXpert software (Hardness edition). Three measurements were taken at each depth, and the average value was determined as the microhardness.

3. Results

3.1. Cutting Force Results

Cutting forces act as a pivotal indicator in machining, directly governing essential process characteristics such as stability, energy usage, and power demand.

Figure 5 illustrates the resultant cutting force data collected from the experimental trials. The reduction in cutting forces observed in UVAM, particularly in the XZ configuration (up to 43% reduction), can be primarily attributed to acousto-plastic softening [

23] and the intermittent cutting mechanism [

5]. In CM, Inconel 718 exhibits severe work hardening ahead of the cutter; consequently, the cutting edges continuously engage with progressively hardened material, leading to elevated forces. When ultrasonic vibrations are superimposed on the tool, the high-frequency oscillatory loading within the primary shear zone promotes dislocation motion and disrupts the dislocation structure, effectively reducing the dynamic flow stress of the alloy [

24]. At the same time, the intermittent tool–workpiece separation characteristic of UVAM shortens the effective contact time. This is particularly beneficial for Inconel 718, whose low thermal conductivity normally causes strong heat accumulation at the cutting edge. The cyclic action of the vibration facilitates chip separation, lubricant/air entrainment, and partial cooling, thereby reducing frictional and thermal loads [

25].

However, the magnitude of this force reduction is heavily dependent on the vibration direction relative to the feed motion. Following the elliptical XZ-mode, X-UVAM achieved the next most significant reduction (31%), markedly outperforming Z-UVAM (17%). The kinematic advantage of X-UVAM stems from the alignment of the vibration vector with the feed direction. By superimposing ultrasonic energy directly along the feed vector, the end mill is mechanically assisted in penetrating the work-hardened material, directly counteracting the feed resistance. Conversely, in Z-UVAM, the oscillatory motion is applied axially—along the spindle axis and orthogonal to the feed direction. While this vertical motion facilitates periodic lifting of the tool and reduces friction on the bottom cutting edges, it provides minimal direct assistance in shearing the material flow in the feed direction. Consequently, the tool in Z-mode must overcome the material’s shear strength with less kinematic assistance than in the X or XZ modes, resulting in the lowest force reduction.

3.2. Surface Roughness Results

The areal surface arithmetic mean height (Sa) values measured on the slots machined during the experiments are shown in

Figure 6. Based on the obtained Sa values, all experiments involving UVAM yielded lower surface roughness values compared to CM. However, the distinct behavior of surface roughness across the three UVAM modes can be explained by considering the elastic recovery and adhesion tendency of Inconel 718. Compared to CM, XZ-UVAM produced the largest improvement, reducing surface roughness by up to 37%, followed by Z-UVAM with 24%, and X-UVAM with 21%. These improvements arise from the periodic tool–workpiece separations produced by ultrasonic vibration, which generate high-frequency microtextures on the machined surface. This interrupts the continuous feed marks characteristic of conventional machining and therefore lowers the surface roughness.

However, when comparing the UVAM modes with each other, the trends differ from the cutting-force results. Although X-UVAM produces lower cutting forces than Z-UVAM, it does not yield the best surface finish. XZ-UVAM achieves surface roughness values that are up to 20% lower than X-UVAM and up to 17% lower than Z-UVAM. Additionally, Z-UVAM produces surfaces that are 4% smoother than those obtained with X-UVAM. This behavior is explained by the deformation and adhesion mechanisms at the tool–workpiece interface. Inconel 718 exhibits significant elastic recovery after tool passage and in X-UVAM, the feed-direction vibration causes the cutting edge to oscillate parallel to the machined surface, increasing the likelihood of flank-face rubbing as the elastically recovered material springs back. Since Inconel 718 readily forms adhesive junctions with the tool [

26], this rubbing promotes material side-flow, smearing, and micro-adhesive damage, which degrades the surface finish despite lower cutting forces.

In contrast, the kinematics of Z-UVAM introduce a vertical lifting component. The axial vibration periodically withdraws the tool from the newly formed surface, breaking adhesive junctions and reducing flank-workpiece rubbing. This suppresses tearing, and smearing defects commonly observed when machining adhesion-prone nickel alloys. Although Z-UVAM contributes less to shear softening and therefore produces higher forces than X-UVAM, its ability to mitigate springback-driven surface damage results in surfaces that are slightly superior (4% lower Ra). The superior performance of XZ-UVAM arises from the combined benefits of both axes: the vertical lifting effect that suppresses adhesion-induced surface damage, and the feed-direction oscillation that enhances chip evacuation and reduces continuous contact.

3.3. Surface Topography and Texture Results

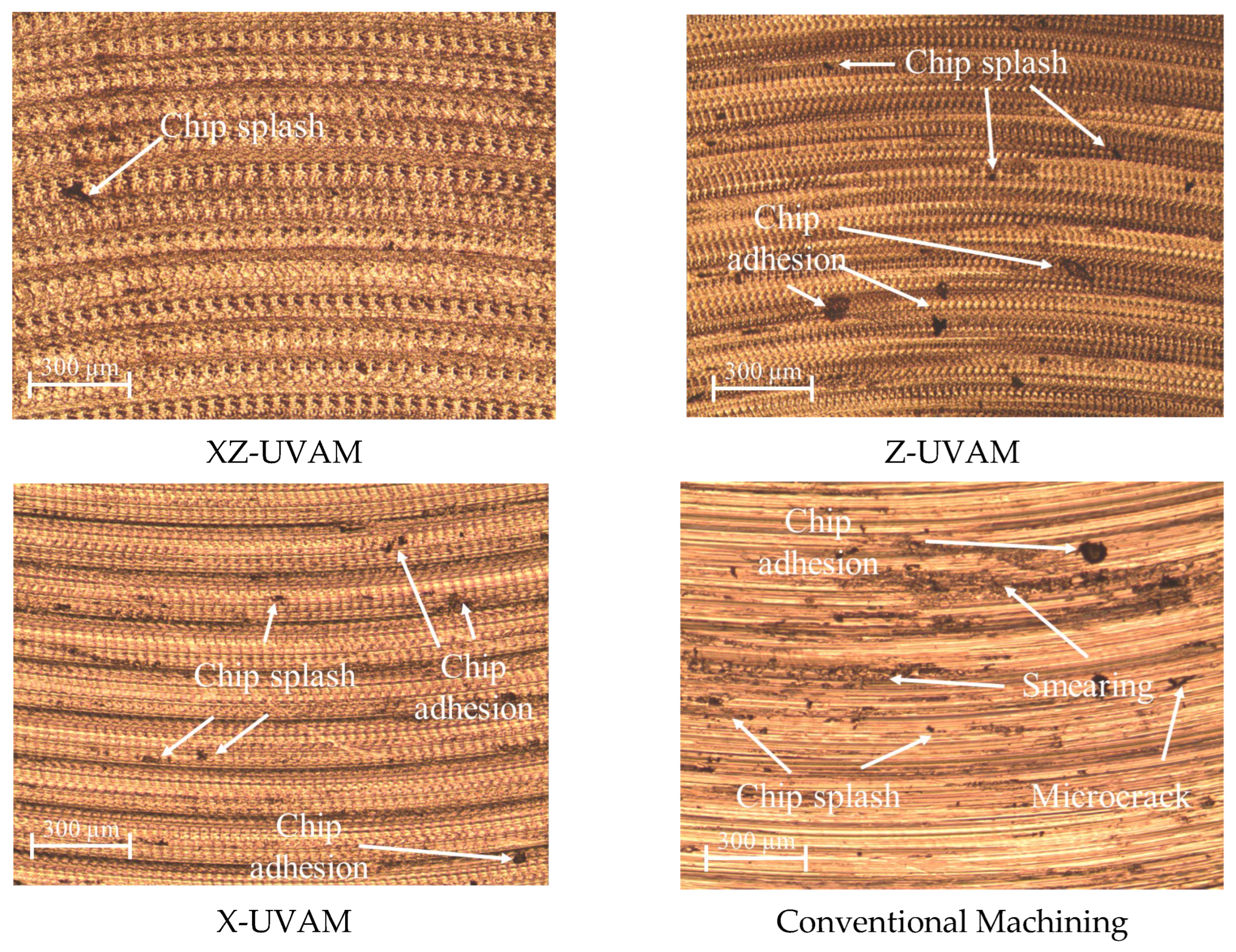

Surface topography is a critical indicator of machining performance because it governs tribological behavior, lubrication efficiency, and the functional life of components—especially in high-demand sectors such as aerospace. The 3D topography maps presented in

Figure 7 and surface texture shown in

Figure 8 clearly reveal the influence of ultrasonic vibration on chip formation and material flow. In CM, the machined surface exhibits deep feed marks, smeared regions, and chip adhesions, all of which are characteristic of continuous cutting in Inconel 718 where poor chip evacuation, severe elastic recovery, and strong adhesion tendencies dominate [

27]. These mechanisms lead to non-uniform height distributions, visible microcracks, and heterogeneous surface zones, indicating unstable thermo-mechanical conditions during cutting. In contrast, all UVAM modes produce markedly improved surfaces with lower peak-to-valley amplitudes. The intermittent tool–workpiece contact inherent to UVAM enhances chip detachment, reduces average contact stresses, and interrupts the formation of smeared layers. This periodic separation also suppresses continuous frictional sliding, thereby promoting more stable material removal. The micro-peaks observed on UVAM surfaces arise from the high-frequency oscillatory motion and represent controlled microtextures rather than damage [

28]. Their reduced amplitude relative to CM indicates more uniform energy input and a more consistent cutting trajectory.

A comparison of vibration directions provides further mechanistic insight. XZ-UVAM yields the lowest peak-to-valley values and the most homogeneous topography. The multidirectional vibration induces both axial and feed-direction oscillations, producing efficient chip fragmentation, reducing rubbing on the freshly generated surface, and minimizing elastic recovery effects. These combined mechanisms generate finely distributed micro-pits that smooth the height distribution and prevent the formation of dominant feed marks, yielding the most uniform surface profile among all conditions. Z-UVAM also produces significantly improved surfaces, characterized by a fish-flake texture and minimal chip adhesion. The axial lifting motion breaks adhesive junctions and limits the tool–workpiece contact time, suppressing severe smearing and local tearing. This explains the more stable height distribution and the lower density of defects compared with CM and X-UVAM. X-UVAM, while superior to CM, exhibits more pronounced feed marks and localized defects than the other UVAM modes. The vibration applied parallel to the cutting direction increases the likelihood of flank rubbing after elastic springback, particularly in an alloy with high adhesion tendency such as Inconel 718. This results in localized material side-flow and occasional microchip residues. Nevertheless, the feed marks appear in a more periodic and stable pattern than in CM, reflecting improved machining stability.

3.4. Subsurface Microhardness Results

Figure 9 presents the subsurface microhardness distributions measured from 50 µm below the machined surface down to the bulk hardness region at approximately 390 µm. All UVAM conditions produced higher subsurface hardness compared with CM. This increase is attributed to the vibration-induced dynamic loading imparted by ultrasonic assistance. The high-frequency oscillations generate repeated impact-like contact events between the tool and the workpiece surface, producing a peening-like effect that enhances plastic deformation, elevating dislocation density within the near-surface layers, and it may even lead to higher compressive residual stresses according to the literature [

29]. Owing to the pronounced work-hardening sensitivity of Inconel 718, this dynamic, high-strain-rate deformation results in a more strongly hardened subsurface layer than the continuous static shearing that characterizes CM.

A clear hierarchy was observed among the vibration directions: Z-UVAM exhibited the highest degree of subsurface hardening, followed by XZ-UVAM, with X-UVAM producing the lowest hardness increase among the assisted modes. This trend is dictated by the vibration kinematics. Axial oscillation of Z-UVAM applies dynamic energy perpendicular to the machined surface, maximizing compressive strain penetration into the subsurface. The repeated normal impacts intensify plastic deformation and produce the most pronounced work-hardened layer. X-UVAM gives the lateral vibration acts parallel to the surface, generating an ironing or friction-dominated interaction rather than a direct normal impact. While still capable of inducing strain hardening, the deformation is more superficial, resulting in the lowest hardness increase in the UVAM modes. While XZ-UVAM combines the kinematic benefits of both axes, it does not result in the highest work hardening. This is because the elliptical trajectory fundamentally alters the impact dynamics. Unlike the Z-UVAM, where impact energy is focused entirely perpendicular to the surface (pure peening), the lateral velocity component in the XZ-mode transforms the vertical impact into a more gradual scooping/sliding motion. Furthermore, the superior acousto-plastic softening observed in XZ-UVAM (evidenced by the lowest cutting forces) partially counteracts the strain hardening mechanism, resulting in a hardness profile that is intermediate between the ironing effect of X-UVAM and the severe hammering of Z-UVAM.

3.5. Burr Formation Results

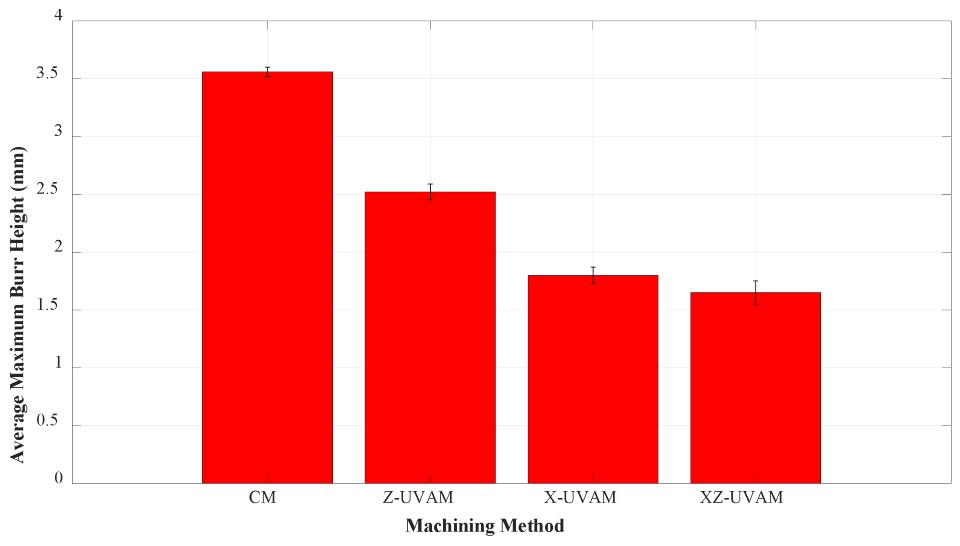

Due to the damaging and time-consuming nature of destructive measurement methods, a non-destructive approach was employed for the burr height measurements. For this purpose, a three-dimensional scan was performed using the Alicona Infinite Focus system over a region measuring 5.3 mm × 12 mm, centered on each slot. Subsequently, a two-dimensional cross-section was extracted from the scanned channel area, and three measurements of the burr height on the upper surface were conducted. Representative three-dimensional images used for burr measurements in the machined channels are presented in

Figure 10. The top burrs were selected for measurement instead of other burrs, as their removal is particularly challenging. The maximum heights of the top burrs were measured from both the up milling and down milling sides, with three measurements taken from each side. The average of these six values was defined as the average maximum upper burr height. The results of the burr height measurements are presented in

Figure 11.

Burr formation is a critical obstacle in machining, as it impairs dimensional accuracy and necessitates additional deburring operations [

30]. In conventional milling, the alloy’s high ductility and pronounced work-hardening tendency promote severe plastic side-flow at the exit region. During tool disengagement, the material at the slot edge undergoes bending rather than fracture initiation, generating a characteristic rollover burr due to insufficient crack formation at the exit boundary [

31]. Introducing ultrasonic vibration meaningfully modifies the burr formation mechanism. The intermittent cutting produced in UVAM decreases the effective tool–workpiece contact time and functions as a dynamic micro-chip-breaker. The periodic separations disrupt the continuous plastic flow that normally feeds burr growth and facilitate the initiation of localized micro-fractures at the burr root and shear zone boundary [

32]. As a consequence, chip detachment occurs earlier in the cutting cycle, reducing the extent of sidewall deformation and limiting the development of large rollover burrs. According to experimental results, the elliptical XZ-mode provided the highest dimensional precision, reducing maximum burr height by 55% compared with CM and outperforming the single-axis modes by 35% relative to Z-UVAM and 8% relative to X-UVAM. A notable finding is that feed-direction vibration (X-UVAM) is more effective than axial vibration (Z-UVAM) for suppressing side burrs. The oscillatory motion parallel to the feed direction enhances shearing along the burr root, mechanically fragmenting early burrs as the tool advances. In contrast, Z-UVAM primarily improves chip evacuation through vertical oscillations but is less effective at disrupting the plastic hinge at the slot edge. The superior performance of XZ-UVAM arises from its hybrid elliptical cutting trajectory, which couples the sidewall shearing action of the X-direction with the vertical chip-fracture assistance of the Z-direction. This synergistic kinematic effect minimizes the residual plastic hinge and yields the lowest burr heights among all tested conditions.

3.6. Statistical Significance of the Results

To validate the experimental findings and determine the statistical significance of the differences between the machining methods (CM, X-UVAM, Z-UVAM, and XZ-UVAM), a statistical analysis was performed using One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with a confidence level of 95% (α = 0.05). Following the ANOVA, Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test was conducted to perform multiple pairwise comparisons and identify specific differences between the experimental groups. The statistical significance of the experimental results was evaluated using the Tukey HSD post hoc test, as summarized in

Table 3.

The analysis reveals that the differences observed between the proposed XZ-UVAM and CM are statistically significant (α = 0.05) across all measured responses. Regarding cutting forces and microhardness, the analysis demonstrated that all pairwise interactions were statistically significant. This implies that each vibration trajectory induces a unique thermo-mechanical state and distinct material response. However, for surface roughness, the difference between X-UVAM and Z-UVAM was found to be statistically insignificant. This outcome can be explained by the fact that both vibration modes mitigate surface damage through competing but comparably effective mechanisms. In X-UVAM, feed-direction oscillation reduces cutting forces and promotes chip segmentation; however, elastic recovery of Inconel 718 increases flank-face rubbing and adhesion-induced smearing, partially offsetting the benefits of force reduction. Conversely, Z-UVAM introduces a vertical lifting effect that intermittently separates the tool from the freshly machined surface, effectively suppressing adhesion-related damage and springback-driven surface degradation, despite higher cutting forces. Notably, with respect to burr height, the analysis revealed no statistically significant difference between X-UVAM and XZ-UVAM. This outcome can be attributed to the dominant role of feed-direction vibration in burr suppression. In both X-UVAM and XZ-UVAM, oscillatory motion along the feed direction promotes effective shearing at the burr root, accelerates crack initiation at the exit edge, and mechanically fragments early burrs before extensive plastic side-flow can develop. Once this feed-direction-driven mechanism is activated, the burr formation process becomes largely governed by exit-edge shearing rather than chip evacuation. While the additional Z-axis vibration in XZ-UVAM enhances intermittent cutting and assists vertical chip fracture, its influence on the exit-edge plastic hinge, which is responsible for burr growth, is secondary. Consequently, the incremental reduction in burr height achieved by adding axial vibration remains modest relative to the dominant X-direction effect and falls within the experimental variability of the measurements.

To further explore these relationships, future research may focus on the multi-objective optimization of vibration directions. By varying the phase shift and amplitude ratios between the X- and Z-axis vibrations, future studies may aim to identify specific transition points at which secondary vibration components yield statistically significant improvements in burr formation, surface roughness or any other machining performance outputs.

4. Limitations and Future Works

This study has presented a comparative assessment of mono-axial and multi-axial UVAM in the slot milling of Inconel 718. The findings demonstrated that XZ-UVAM produced the most favorable outcomes among the tested methods, providing notable reductions in cutting forces, surface roughness, and burr height while enhancing subsurface integrity. Despite these promising results, several limitations should be acknowledged, and future studies are warranted to further expand on these findings. First, the experiments were conducted at a single spindle speed and feed rate that corresponded to a chatter-free stable region. Consequently, the observed trends in force reduction and surface improvement represent the specific conditions tested. Since spindle speed directly affects tool–chip interaction dynamics, heat generation, and strain rate effects, additional tests at various spindle speeds would help generalize the applicability of the present results. Future investigations should incorporate statistically designed experiments that consider the key control factors of all four processes. Applying multi-response optimization methods will help integrate multiple performance metrics and provide a more explicit assessment of the most advantageous process and operating conditions.

Also, the current investigation primarily focused on surface and near-surface characteristics. A more detailed microstructural analysis involving residual stress, grain refinement, and fatigue behavior would provide valuable insights into the long-term mechanical performance of components machined by UVAM.

Another limitation is related to the phase relationship between the X and Z directional ultrasonic vibrations in the multi-axial (XZ-UVAM) configuration. In this study, the phase difference between the two ultrasonic systems was not actively controlled. It is anticipated that controlling and tuning the phase difference may significantly influence the resultant tool tip trajectory and contact dynamics. Therefore, future research should focus on developing a synchronized control system for multi-axial ultrasonic vibration to systematically investigate the effect of phase difference on process performance. Additionally, future studies should explore the influence of variable cutting parameters to further optimize process stability. Investigating these factors will help solidify multi-axial UVAM as a sustainable and high-quality machining strategy for nickel-based superalloys.