A Review on Cutting Force and Thermal Modeling, Toolpath Planning, and Vibration Suppression for Advanced Manufacturing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cutting Force/Temperature Modeling

2.1. Analytical Model

2.2. Numerical Model

2.3. Machine Learning

2.4. Integrated Discussion on Cutting Force/Temperature Modeling

3. Tool Path Planning

3.1. Mathematical Methods in Tool Path Planning

- (1)

- Precision and error control. Optimized algorithms can compensate for robotic absolute positioning errors, significantly enhancing path accuracy. Combining techniques such as the constant residual height method and smoothing algorithms improves machining smoothness and precision [133].

- (2)

- Full-process optimization. Tool path planning should integrate more closely with process planning, cutting parameter optimization, error compensation, and online inspection to form a closed-loop intelligent machining system [134].

- (3)

- Big data cloud-based collaborative control. Complex tool path planning algorithms for subsequent machining stages can be executed in the cloud, while lightweight models or instructions are downloaded to the machine tool for execution, addressing computational resource bottlenecks.

3.2. Integrated Discussion on Tool Path Planning

4. Vibration Suppression

4.1. Mathematical Methods in Vibration Suppression

4.2. Integrated Discussion on Vibration Suppression

5. Conclusions and Outlook

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- The methodology for cutting force and temperature modeling has become increasingly sophisticated. From analytical models based on shear-slip theory and finite-element numerical simulations capable of revealing intricate details in complex physical fields, to data-driven ML models that do not require explicit physical equations, each approach possesses distinct advantages and applicable scenarios. Among these, hybrid modeling that integrates physical laws with data science demonstrates significant potential to overcome the limitations of traditional models, positioning it as a frontier for future research.

- (2)

- Tool path planning has progressed from a purely geometric task to a multi-objective optimization problem. The mathematical toolkit has expanded from computational geometry (NURBS curves, iso-scallop tool paths) to graph theory (shortest-path search), metaheuristic algorithms (genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization for machining sequence planning), and real-time control theory. Today, physically constrained path planning is mainstream, requiring paths to satisfy not only geometric accuracy but also physical objectives such as stable cutting forces, vibration suppression, and thermal management.

- (3)

- Vibration suppression relies on a mathematically grounded ‘modeling–sensing–control’ framework. This spans stability lobe theory rooted in time-delay differential equations, state identification using Fourier transforms, wavelet analysis, and machine learning, to active control strategies based on modern control theory (such as adaptive control). Together, these mathematical tools provide a systematic methodology for analyzing, predicting, and mitigating vibrations during machining.

5.2. Industrial Application Challenges

5.3. Outlook

- (1)

- Deep integration and systemization: Future research can seamlessly integrate multiple modules, including cutting force/temperature models, path planning, and vibration suppression, into a comprehensive ‘digital twin’ framework through mathematical methods. Developing efficient multiphysics coupling algorithms enables real-time interaction and bidirectional optimization between virtual spaces and physical machine tools, forming an autonomous closed-loop system of ‘perception-decision-control’. Additionally, exploring how to more effectively embed prior knowledge, such as physics conservation laws and boundary conditions, into deep learning architectures addresses the weak generalization capabilities and poor interpretability of pure data models.

- (2)

- Specialized solutions for complex machining scenarios: Existing general-purpose models may prove inadequate for new processes and materials such as composite materials, superhard material machining, micro/nano machining, and additive–subtractive hybrid manufacturing. There is an urgent need to develop specialized constitutive models, damage criteria, and path generation algorithms tailored to these applications, alongside establishing toolpath optimization databases for high-performance manufacturing of complex curved components. For example, for carbon fiber composite materials, one can establish a specialized constitutive model that can characterize anisotropic cutting forces and interlayer delamination damage; thus, developing multi-scale simulation methods that consider size effects and grain orientation for micro milling. Secondly, by utilizing limited experimental data on new materials through transfer learning, a reliable set of tool path optimization parameters can be quickly generated.

- (3)

- Application of autonomous intelligence and reinforcement learning: Current optimization heavily relies on offline algorithms. Autonomous intelligence based on deep reinforcement learning enables agents to interact with the machining environment through trial and error. This approach facilitates the development of higher-level autonomous optimization systems for machining strategies. Autonomous learning algorithms acquire optimal vibration suppression strategies, tool path parameters, or cooling strategies, ultimately forming an “adaptive machining decision center” capable of handling unknown conditions and self-evolving and adjusting. Examples of this include deploying ML in the digital twin of the machining process, designing a high-fidelity virtual environment that can comprehensively reflect vibration, force/heat, tool wear, and other states, as well as a multi-objective function that considers efficiency, quality, and stability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Shen, Z.; Li, X.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Xiao, J.; Xu, J. Investigation on the machinability of copper-coated monocrystalline silicon by applying elliptical vibration diamond cutting. Precis. Eng. 2023, 82, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Du, Y.; Diao, Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, Y. Modeling and analysis of the cutting temperature of titanium alloys for quasi-intermittent vibration assisted swing cutting. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 5191–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Niu, Y. Mechanical drilling force model for longitudinal ultrasonic vibration-assisted drilling of unidirectional CFRP. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 319, 118091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazma Sultana, M.; Ranjan Dhar, N. Milling force modelling with high-pressure cooling strategy: An integrated analytical approach. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amigo, F.J.; Urbikain, G.; López de Lacalle, L.N.; Pereira, O.; Fernández-Lucio, P.; Fernández-Valdivielso, A. Prediction of cutting forces including tool wear in high-feed turning of Nimonic® C-263 superalloy: A geometric distortion-based model. Measurement 2023, 211, 112580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, C.; Cheung, C.F.; Wang, C.; Li, K.; Bulla, B. Micro/nano incremental material removal mechanisms in high-frequency ultrasonic vibration-assisted cutting of 316L stainless steel. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2023, 191, 104064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehranizadeh, F.; Berenji, K.R.; Yıldız, S.; Budak, E. Chatter stability of thin-walled part machining using special end mills. CIRP Ann. 2022, 71, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, K.; Lin, C.; Huang, W.; Chen, X.; Xiao, J.; Xu, J. Field-assisted machining of difficult-to-machine materials. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 32002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azami, A.; Salahshournejad, Z.; Shakouri, E.; Sharifi, A.R.; Saraeian, P. Influence of nano-minimum quantity lubrication with MoS2 and CuO nanoparticles on cutting forces and surface roughness during grinding of AISI D2 steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 87, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, Z.; Wang, D.; Liu, L. Theoretical analysis of cooling mechanism in high-speed ultrasonic vibration cutting interfaces. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 184, 108033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Xu, G.; Wang, G.; Zhao, M. Effect of high-speed ultrasonic vibration cutting on the microstructure, surface integrity, and wear behavior of titanium alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 3870–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wu, B.; Yue, Y.; Ding, W.; Xu, J.; Guo, G. Developing a novel radial ultrasonic vibration-assisted grinding device and evaluating its performance in machining PTMCs. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yan, B.; Qin, S.; Cui, D.; Lu, H. Milling chatter detection with WPD and power entropy for Ti-6Al-4V thin-walled parts based on multi-source signals fusion. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 177, 109225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhai, D. Study on wavy-edge plunge milling cutter with chip split and cutting load reduction function. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 102, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Li, L.; Jia, S.; Jiang, Z.; Duan, X.; Lai, K.-H.; Cai, W. Multi-objective optimisation for energy saving and high efficiency production oriented multidirectional turning based on improved fireworks algorithm considering energy, efficiency and quality. Energy 2023, 284, 129205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zannoun, H.; Schoop, J. Analysis of burr formation in finish machining of nickel-based superalloy with worn tools using micro-scale in-situ techniques. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2023, 189, 104030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, P.; Fan, H.; Bartoň, M. Efficient 5-axis CNC trochoidal flank milling of 3D cavities using custom-shaped cutting tools. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2022, 151, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Chen, S.; Song, K.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y. A novel trajectory planning method based on reverse compensation of profile error for robotic belt grinding of blisk. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 84, 508–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harabin, G.P.; Behandish, M. Hybrid Manufacturing Process Planning for Arbitrary Part and Tool Shapes. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2022, 151, 103299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Qian, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, G. Multi-Objective Redundancy Optimization of Continuous-Point Robot Milling Path in Shipbuilding. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 134, 1283–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jia, J.; Xu, J.; Chen, M.; Niu, J. Path, feedrate and trajectory planning for free-form surface machining: A state-of-the-art review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, L.; Fan, C.; Wang, H. High-order joint-smooth trajectory planning method considering tool-orientation constraints and singularity avoidance for robot surface machining. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 80, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Yu, H.; Li, Z.; Lin, J. Tool path planning of consecutive free-form sheet metal stamping with deep learning. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 303, 117530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, X.; Shi, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, R. Data-driven bending fatigue life forecasting and optimization via grinding Top-Rem tool parameters for spiral bevel gears. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 53, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, L.; Yu, G. Chatter prediction in flank milling of thin-walled parts considering force-induced deformation. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 165, 108314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, C.; Jia, J.; Ma, B.; Jiang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhu, T. High-order semi-discretization methods for stability analysis in milling based on precise integration. Precis. Eng. 2022, 73, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, M.; Song, Y.; Mei, J. Analysis and modeling of cutting force considering the tool runout effect in longitudinal-torsional ultrasonic vibration-assisted 5 axis ball end milling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 318, 118012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Wang, S.; Mao, X.; Liu, H.; Liang, Z.; Guo, Q.; Yan, R. Forced vibration mechanism and suppression method for thin-walled workpiece milling. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 230, 107553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamada, Y.; Kitakaze, A.; Sannomiya, K.; Nakaya, T.; Sasahara, H. Mechanism to suppress regenerative chatter vibration due to the effect of air-cutting and multiple regeneration during low frequency vibration cutting. Precis. Eng. 2022, 78, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picavea, J.; Gameros, A.; Yang, J.; Axinte, D. Vibration suppression using tuneable flexures acting as vibration absorbers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 222, 107238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.; Brock, G.; Saelzer, J.; Biermann, D. Avoiding process vibrations by suppressing chip segmentation during machining of aerospace alloy Ti6Al4V. Procedia CIRP 2022, 115, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, S.; Jaiswal, M.; Pratap Narain, R.; Singh, S.; Shrivastava, Y. A short review on investigation and suppression of tool chatter in turning operation. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 51, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Penter, L.; Hänel, A.; Ihlenfeldt, S.; Wiercigroch, M. Stability enhancement and chatter suppression in continuous radial immersion milling. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 235, 107711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozsoy, M.; Sims, N.D.; Ozturk, E. Robotically assisted active vibration control in milling: A feasibility study. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 177, 109152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhao, B.; Ding, W.; Xin, L. Nontraditional energy-assisted materials and components in aerospace community: A comparative analysis. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 22007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, Y.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Ding, W.; Lei, X.; Wu, B.; Zhang, M.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Overcoming challenges: Advancements in cutting techniques for high strength-toughness alloys in aero-engines. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 62012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; Kumar Gupta, M.; da Silva, L.R.R.; Kiran, M.; Khanna, N.; Krolczyk, G.M. Application of measurement systems in tool condition monitoring of Milling: A review of measurement science approach. Measurement 2022, 199, 111503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, Z.; Hao, Y.; Teng, Y. Electrochemical cutting with flexible electrode of controlled online deformation. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 7, 15104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yan, Y.; Cui, J.; Geng, Y.; Sun, T.; Luo, X.; Zong, W. Recent advances in design and preparation of micro diamond cutting tools. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 62008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Zhao, G.; Nian, Z.; Yang, H.; Li, L.; He, N. Physics-based modeling and mechanism of polycrystalline diamond tool wear in milling of 70 vol% Si/Al composite. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 7, 55102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liao, W.; Zheng, K.; Tian, W.; Liu, J.; Feng, J. Stability analysis of robotic longitudinal-torsional composite ultrasonic milling. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, J. Micro-amplitude vibration-assisted scratching: A new method for one step and controllable fabrication of the microscale V-groove and nanoscale ripples. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2025, 7, 35102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yin, J.; Ding, W.; Xu, J. Alumina abrasive wheel wear in ultrasonic vibration-assisted creep-feed grinding of Inconel 718 nickel-based superalloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 297, 117241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhang, H.; Kang, R.; Ran, Y.; Bao, Y. Mechanical modeling of ultrasonic vibration helical grinding of SiCf/SiC composites. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 234, 107701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Xin, M.; Song, Q.; Jiang, L. Longitudinal amplitude effect on material removal mechanism of ultrasonic vibration-assisted milling 2.5D C/SiC composites. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 32144–32152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Ran, Y.; Kang, R. On understanding the mechanical properties and damage behavior of C f / SiC composites by indentation method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 3784–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Bao, Y. Effect of tool wear on machining quality in milling Cf/SiC composites with PCD tool. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 105, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Cao, H.; Zheng, W.; Qu, D.; Liu, L.; Yan, C. Cutting force modeling of machining carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites: A review. Compos. Struct. 2022, 299, 116096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, J.; Ayvar-Soberanis, S.; Dominguez-Caballero, J.; Onawumi, P.; Kilic, Z.M.; Curtis, D. Assessment of cutting force coefficient identification methods and force models for variable pitch and helix bull-nose tools. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 55, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, D.Y. In-Process Identification of the Cutting Force Coefficients in Milling based on a Virtual Machining Model. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2022, 23, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Z.; Guo, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, S. Cutting Force Modeling Considering Wiper Edge Cutting Effect During Face Milling of 316H Stainless Steel and Experimental Verification. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2024, 37, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yang, Z.; Huang, S.; He, Y.; Huang, Z.; Tuo, J. A hybrid modeling method for predicting the cutting force in whirlwind milling of lead screw. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 106, 265–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Liu, Z.; Song, Q.; Wang, B.; Cai, Y. Prediction modelling of cutting force in rotary ultrasonic end grinding 2.5D woven SiO2f/SiO2 ceramic matrix composite. Compos. Struct. 2023, 304, 116448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Hu, P.; Chen, J.; Han, W.; Wang, R. Deep learning-based instantaneous cutting force modeling of three-axis CNC milling. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 246, 108153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Axinte, D.; Gao, D. On modelling of cutting force and temperature in bone milling. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 266, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wei, R.; Cao, L.; Li, J.; Xiong, X.; Yu, L.; Li, C.; Ko, T.J. Cutting force modeling and machinability investigation of Inconel 718 using ultrasonic vibration-electrical discharge assisted milling. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 136, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, X.; Zhu, K. Cutting Force and State Identification in High-Speed Milling: A Semi-Analytical Multi-Dimensional Approach. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 38, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, G.; Alkahtani, M.; Alsultan, M.; Buhl, J.; Kumar Gupta, M. Chip formation, cutting temperature and forces measurements in hard turning of Gcr15 under the influence of PcBN chamfering parameters. Measurement 2022, 204, 112130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Dang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B.; Mu, C. Prediction method for milling force coefficients based on energy consumption signal in ball-end milling process. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, B.; Ding, W.; Jia, X.; Wu, B.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Xu, D. Evolution of undeformed chip thickness and grinding forces in grinding of K4002 nickel-based superalloy using corundum abrasive wheels. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 38, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.; Zhang, X.; Shen, B.; Zhang, D. An improved analytical model of cutting temperature in orthogonal cutting of Ti6Al4V. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2019, 32, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Zhao, L.; Chen, M.; Cheng, J.; Chen, G.; Lei, H.; Liu, Z.; Geng, F.; Wang, S.; Xu, Q. Determination of stress waves and their effect on the damage extension induced by surface defects of KDP crystals under intense laser irradiation. Optica 2023, 10, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Chen, M.; Cheng, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, L.; Yang, H.; Cheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Tan, C. Laser damage evolution by defects on diamond fly-cutting KDP surfaces. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 237, 107794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ming, W.; An, Q.; Chen, M. Mechanism and feasibility of ultrasonic-assisted milling to improve the machined surface quality of 2D Cf/SiC composites. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 15122–15136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Liu, Z.; Han, L.; Wang, B.; Xin, M.; Cai, Y.; Song, Q. Optimizing amplitude to improve machined surface quality in longitudinal ultrasonic vibration-assisted side milling 2.5D C/SiC composites. Compos. Struct. 2022, 297, 115963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Song, Q.; Fu, H.; Ji, H.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, L. Fiber orientation effects on grinding characteristics and removal mechanism of 2.5D Cf/SiC composites. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein Rabiee, A.; Tahmasbi, V.; Qasemi, M. Experimental evaluation, modeling and sensitivity analysis of temperature and cutting force in bone micro-milling using support vector regression and EFAST methods. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 120, 105874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Nian, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; He, N. Enhancing the machinability of Cf/SiC composite with the assistance of laser-induced oxidation during milling. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 1651–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.P.; Zhuang, X.H.; Fan, Y.H. Study of cutting force of SiCp/Al composites based on acoustic-plasticity intrinsic model. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 61, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Hartmaier, A.; Xu, J.; Yan, Y.; Sun, T. Cutting path-dependent machinability of SiCp/Al composite under multi-step ultra-precision diamond cutting. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2021, 34, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; An, Q.; Chen, M. Microstructure evolution and ablation mechanism of SiCf/SiC ceramic matrix composite microgrooves processed by pico-second laser. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 37356–37365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Geng, F.; Chen, M. Determination of intrinsic defects of functional KDP crystals with flawed surfaces and their effect on the optical properties. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 10041–10050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Jin, X.; Fu, R.; Shi, Y. Numerical prediction of the chip formation and damage response in CFRP cutting with a novel strain rate based material model. Compos. Struct. 2022, 294, 115746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, C.H.; Rezvani, S.; Lee, J.; Park, S.S.; Park, H.W.; Lee, J. Indirect measurement of cutting forces during robotic milling using multiple sensors and a machine learning-based system identifier. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 85, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Z.; Jia, C.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y. Investigating the cutting force of disc cutter in multi-cutter rotary cutting of sandstone: Simulations and experiments. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2022, 152, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Xiang, D.; Yuan, Z.; Song, C.; Gao, G.; Tong, J.; Zhao, B. Laser-assisted ultrasonic elliptical vibration turning of high-volume fraction SiCp/Al force-thermal research. Mater. Des. 2025, 257, 114525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Liu, Y.; Ding, L.; Zhou, J.; M’Saoubi, R.; Liu, H. Experimental and numerical investigation of Inconel 718 machining with worn tools. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 77, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Outeiro, J.; Zhuang, K.; Birembaux, H. Selection of the numerical formulation for modeling the effect of tool cutting edge microgeometries in machining of Ti6Al4V titanium alloy. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2023, 129, 102816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jin, Y.; Gao, M.; Shu, D.; Ding, F.; Chen, M.; Wang, B. Optimization of multi-step cutting strategies for SiCp/Al composites: A thermo-mechanical coupled simulation and experimental study. Mater. Des. 2025, 260, 115144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bao, Y.; Feng, K.; Li, B.; Dong, Z.; Kang, R.; Wang, Y. Characterization, quantitative evaluation, and formation mechanism of surface damage in ultrasonic vibration assisted scratching of Cf/SiC composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 4502–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; An, W.; Gao, M.; Fu, Y. Femtosecond laser ablation behavior of SiC/SiC composites in air and water environment. Corros. Sci. 2022, 208, 110671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.; Fast, M.; Saelzer, J.; Brock, G.; Biermann, D.; Turek, S. Modeling and validation of a FEM chip formation simulation to expand the numerical work on discontinuous drilling of Inconel 718. Procedia CIRP 2023, 117, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H. Mediating compositional machining difference of UD-CFRP in orthogonal cutting by epoxy coating. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 258, 110706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, G.; Xu, X.; Xuan, S.; Fan, X.; Kan, Y.; Yao, X. Thermal–mechanical coupling numerical simulation and low damage analysis for drilling composite. Compos. Struct. 2023, 324, 117542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Hu, G.; Hou, N.; Liu, N.; Wang, M. Numerical and experimental investigations on the laser assisted machining of the TC6 titanium alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 96, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.F.; Wang, W.H.; Jiang, R.S.; Huang, B.; Liu, C. Feasibility and tool performance of ultrasonic vibration-assisted milling-grinding SiCf/SiC ceramic matrix composite. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 19, 3018–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.; Hao, B.; Wei, S.; Qiu, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, G. Study on anisotropic heat transfer and thermal damage in nanosecond pulsed laser processing of CFRP. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 5964–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Chen, M.; Wang, G.; Zhou, X. Milling force prediction and optimization of process parameters in micro-milling of glow discharge polymer. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 122, 1293–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhao, B.; Qiu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Tang, M.; Deng, M.; Liu, G.; Ding, W. MOPSO process parameter optimization in ultrasonic vibration-assisted grinding of hardened steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 128, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Zhou, X.; Song, J. Experimental investigation on cutting force and machining parameters optimization in in-situ laser-assisted machining of glass–ceramic. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 169, 110109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, B. Machine learning algorithms—A review. Int. J. Sci. Res. (IJSR) 2020, 9, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Tian, G.; Chen, M.; Tao, F.; Zhang, C.; Ai-Ahmari, A.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Z. Dual-objective program and improved artificial bee colony for the optimization of energy-conscious milling parameters subject to multiple constraints. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geißel, L.; Wiederkehr, P. Bayesian approach to determine force model parameters for the prediction of cutting forces in turning operations. Procedia CIRP 2023, 117, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Dubey, V.; Kumar Sharma, A. Comparative analysis of different machine learning algorithms in prediction of cutting force using hybrid nanofluid enriched cutting fluid in turning operation. Mater. Today Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi Araghizad, A.; Pashmforoush, F.; Tehranizadeh, F.; Kilic, K.; Budak, E. Improving milling force predictions: A hybrid approach integrating physics-based simulation and machine learning for remarkable accuracy across diverse unseen materials and tool types. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 114, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, A.; Davis, J.B.; dos Santos e Lucato, S.L. Novel approach to rapid and accurate temperature-dependent mechanical testing using machine learning. Mater. Des. 2026, 261, 115307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Chen, F.; Zhou, T.; Yao, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, D.; He, L. Design and performance analysis of wear-resistant micro-groove cutting tool: Numerical simulation and experimental study. Mater. Des. 2025, 256, 114344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogl, G.W.; Qu, Y.; Eischens, R.; Corson, G.; Schmitz, T.; Honeycutt, A.; Karandikar, J.; Smith, S. Cutting force estimation from machine learning and physics-inspired data-driven models utilizing accelerometer measurements. Procedia CIRP 2024, 126, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajhi, W.; Ibrahim, A.M.M.; Mourad, A.H.I.; Boujelbene, M.; Fujii, M.; Elsheikh, A. Prediction of milled surface characteristics of carbon fiber-reinforced polyetheretherketone using an optimized machine learning model by gazelle optimizer. Measurement 2023, 222, 113627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.P.; Tsai, H.H.; Chang, J.Y. Machine-Learning-Based Optimal Feed Rate Determination in Machining: Integrating GA-Calibrated Cutting Force Modeling and Vibration Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Huang, Z.; Du, J.; Wu, H. Efficient identification of cutter axis offset in five-axis ball-end interrupted milling using twin data method free from cutting force model. Precis. Eng. 2024, 91, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, B.; Kantheti, P.; Rathore, S.; Kanabar, B.; Thulasiram, R.; Kumar, M.; Bhowmik, A.; Santhosh, A.J. A Multi-Objective optimization framework for the sustainable machining of Monel 400. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.; Zhang, W.H.; Qin, G.H.; Tan, G. Efficient calibration of instantaneous cutting force coefficients and runout parameters for general end mills. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2007, 47, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Rong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, G. Revealing thermal-mechanical hybrid ablation mechanism in carbon fiber reinforced plastic laser cutting by acoustic emission monitoring. Measurement 2023, 221, 113473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Feng, P.; Zhang, M. Determination of tool tip steady-state temperature in dry turning process based on artificial neural network. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 79, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Jing, X.; Yang, Z.; Xu, W. Optimization of multistage femtosecond laser drilling process using machine learning coupled with molecular dynamics. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 156, 108442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, C.; Sun, C.; Cui, H.; Tian, P.; Du, F.; He, L. Hybrid modeling with finite element—Analysis—Neural network for predicting residual stress in orthogonal cutting of H13. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 4954–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelekci, E.; Kizir, S. A novel tool path planning and feedrate scheduling algorithm for point to point linear and circular motions of CNC-milling machines. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 95, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhouib, S.; Zouari, A. Adaptive iterated stochastic metaheuristic to optimize holes drilling path in manufacturing industry: The Adaptive-Dhouib-Matrix-3 (A-DM3). Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 120, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Lou, F.; Guo, P. Mixed tiny path smoothing method based on sliding convolution windows for CNC machining. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 102, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, P.; Li, H.; Lou, F. Five-axis path smoothing based on sliding convolution windows for CNC machining. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 49, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Tang, B.; Qiu, J. A novel tool path planning method for machining triangular mesh surfaces based on geodesics in heat theory. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 108, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, J.; Yan, W.; Xin, S.; Xu, J. A fast and precise filament winding path planning method based on discrete non-iterative semi-geodesic algorithm for all applicable mandrel. Compos. Commun. 2023, 40, 101620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Liu, L.; Zou, Q.; Fu, X.M. Computing smooth preferred feed direction fields with high material removal rates for efficient CNC tool paths. CAD Comput. Aided Des. 2023, 164, 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xu, H.; Li, H.; Gao, H.; Wang, H. A cutter contacting point trajectory prediction method combining harmonic functions and dimensionality reduction for improving machining precision in flat-end milling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Liu, H.; Huang, T.; Han, J.; Xiao, J. An effective approach for non-singular trajectory generation of a 5-DOF hybrid machining robot. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2023, 80, 102477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Xu, G.; Lu, H.; Qin, S.; Zhu, C. Identification of milling information and cutter-workpiece engagement in five-axis finishing of turbine blades based on NURBS and NC codes. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 107, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Wei, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, S. A New Dynamics Analysis Model for Five-Axis Machining of Curved Surface Based on Dimension Reduction and Mapping. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 36, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaroleta, M.; Treter, G.; Nowak, K. Modified tool radius compensation in the Archimedes’ spiral tool path for high speed machining of circular geometry. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 97, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.S.; Yen, S.H.; Bedaka, A.K.; Shah, S.H.; Lin, C.Y. Trajectory planning method with grinding compensation strategy for robotic propeller blade sharpening application. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 86, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarri, M.; Bo, P.; Bartoň, M. Screw rotor manufacturing via 5-axis flank CNC machining using conical tools. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2023, 100, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Xuan, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Han, W. A novel tool path planning method for 5-axis single-point diamond turning. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 124, 1438–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.Y.; Lyu, B.; Ma, H.Y.; Chen, S.P. Single start end tool path generation for arbitrary porous surfaces. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 132, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M. An Optimization Method for Five-axis Plunge Milling Tool Path Considering SIRD. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 38, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreja, A.; Pande, S.S. Optimal toolpath planning strategy prediction using machine learning technique. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 123, 106464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingartshofer, T.; Bischof, B.; Meiringer, M.; Hartl-Nesic, C.; Kugi, A. Optimization-based path planning framework for industrial manufacturing processes with complex continuous paths. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2023, 82, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Sun, Y.; Xu, J. Tool path generation for 5-axis flank milling of ruled surfaces with optimal cutter locations considering multiple geometric constraints. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.Z.; Chen, J.N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.Q.; Zhu, L.M. “4+2” axis ultra-precision diamond shaping for partially overlapping Fresnel lenses based on an ultra-precision machine tool and two additional rotational axes. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 99, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, X.; Kang, J.; Yao, T.; Cheng, B.; Li, M.; Xie, Q. Spiral tool path optimization method for fast/slow tool servo-assisted diamond turning of freeform surfaces with highly form accuracy. Precis. Eng. 2023, 80, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Duan, W.; Wu, H.; Chen, M.; Zeng, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y. Investigation on the ultra-precision diamond turning of ZnSe aspheric surfaces using straight-nosed cutting tools. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 104, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacso, A.; Lado, Z.; Phanden, R.K.; Sikarwar, B.S.; Singh, R.K. Bézier curve-based trochoidal tool path optimization using stochastic hill climbing algorithm. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 78, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Rong, S.; Rong, K.; Tang, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, G. Life cycle assessment-driven collaborative optimization model of power dry cutting for face-hobbing hypoid gear production. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ma, Y.; Luo, T.; Cao, S.; Huang, Z. Fabrication of hierarchical micro-groove structures by vibration assisted end fly cutting. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 322, 118164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Lu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, T. Surface texture topography evaluation and classification by considering the tool posture changes in five-axis milling. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 101, 1343–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Liao, W.; Zheng, K.; Dong, S.; Lei, P.; Sun, L. Chatter stability of robotic rotary ultrasonic countersinking. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gao, D.; Hong, D.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zan, S.; Liao, Z. Improving generalisation and accuracy of on-line milling chatter detection via a novel hybrid deep convolutional neural network. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 193, 110241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, H.; Shokrani, A. Investigation of chatter detection with sensor-integrated tool holders based on strain measurement. Procedia CIRP 2023, 117, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eto, J.; Hayasaka, T.; Shamoto, E. Proposal of novel chatter-free milling strategy utilizing extraordinarily numerous flute endmill and high-speed high-power machine tool. Precis. Eng. 2023, 80, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yan, L.; Zhu, K.; Jiang, P.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, X. An all-composite sandwich structure with PMI foam-filled for adjustable vibration suppression and improved mechanical properties. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 196, 111544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, M.; Liu, Z.; Che, C.; Zan, T.; Gao, X.; Gao, P. Tool wear process monitoring by damping behavior of cutting vibration for milling process. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 102, 1069–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Qi, S.; Sun, Y. Cutting conditions dependent adjustment of dynamic responses for slender tools in internal turning with a flexible vibration suppression device. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 113, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, G.; Zong, W.; Tang, Y. Statistical analysis and suppression of vibration frequency bifurcation in diamond turning of Al 6061 mirror. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 198, 110421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Sun, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhu, B.; Wu, W.; Ren, Y.; Liu, W. An adaptive active vibration suppression method for diverse wind tunnel aircraft models. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2025, 39, 103729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J. Adaptive milling chatter identification based on sparse dictionary considering noise estimation and critical bandwidth analysis. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 106, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.B.; Geng, L.; Zhang, Y.F.; Liu, K.; Ng, T.E. Cutting force prediction for five-axis ball-end milling considering cutter vibrations and run-out. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2015, 96–97, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Sun, S.; Pan, Z.; Ding, D.; Gienke, O.; Li, W. Mode coupling chatter suppression for robotic machining using semi-active magnetorheological elastomers absorber. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 117, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Tang, X.; Chen, C.; Peng, F.; Yan, R.; Zhou, L.; Li, Z.; Wu, J. High precision and efficiency robotic milling of complex parts: Challenges, approaches and trends. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Pan, Z.; Ding, D.; Sun, S.; Li, W. A Review on Chatter in Robotic Machining Process Regarding Both Regenerative and Mode Coupling Mechanism. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 2240–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Tang, X.; Xin, S.; Wang, C.; Peng, F.; Yan, R. Research on the directionality of end dynamic compliance dominated by milling robot body structure and milling vibration suppression. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2024, 85, 102631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, H.; Sun, Y.; Song, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, Z. An interpretable anti-noise convolutional neural network for online chatter detection in thin-walled parts milling. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 206, 110885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Cao, J.; Hu, Y. In-process feature extraction of milling chatter based on second-order synchroextracting transform and fast kutrogram. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 208, 111018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.X.; Mo, J.L.; Xiang, Z.Y.; Wang, Q.; Yu, Z.; Zhai, C.Z.; Zhu, S. Effect of surface micro-grooved textures in suppressing stick-slip vibration in high-speed train brake systems. Tribol. Int. 2023, 189, 108946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totis, G.; Sortino, M. Superior optimal inverse filtering of cutting forces in milling of thin-walled components. Measurement 2023, 206, 112227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Peng, G.; Li, Z.; Li, W.; Sun, L. Low-frequency vibration isolation via an elastic origami-inspired structure. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 260, 108622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

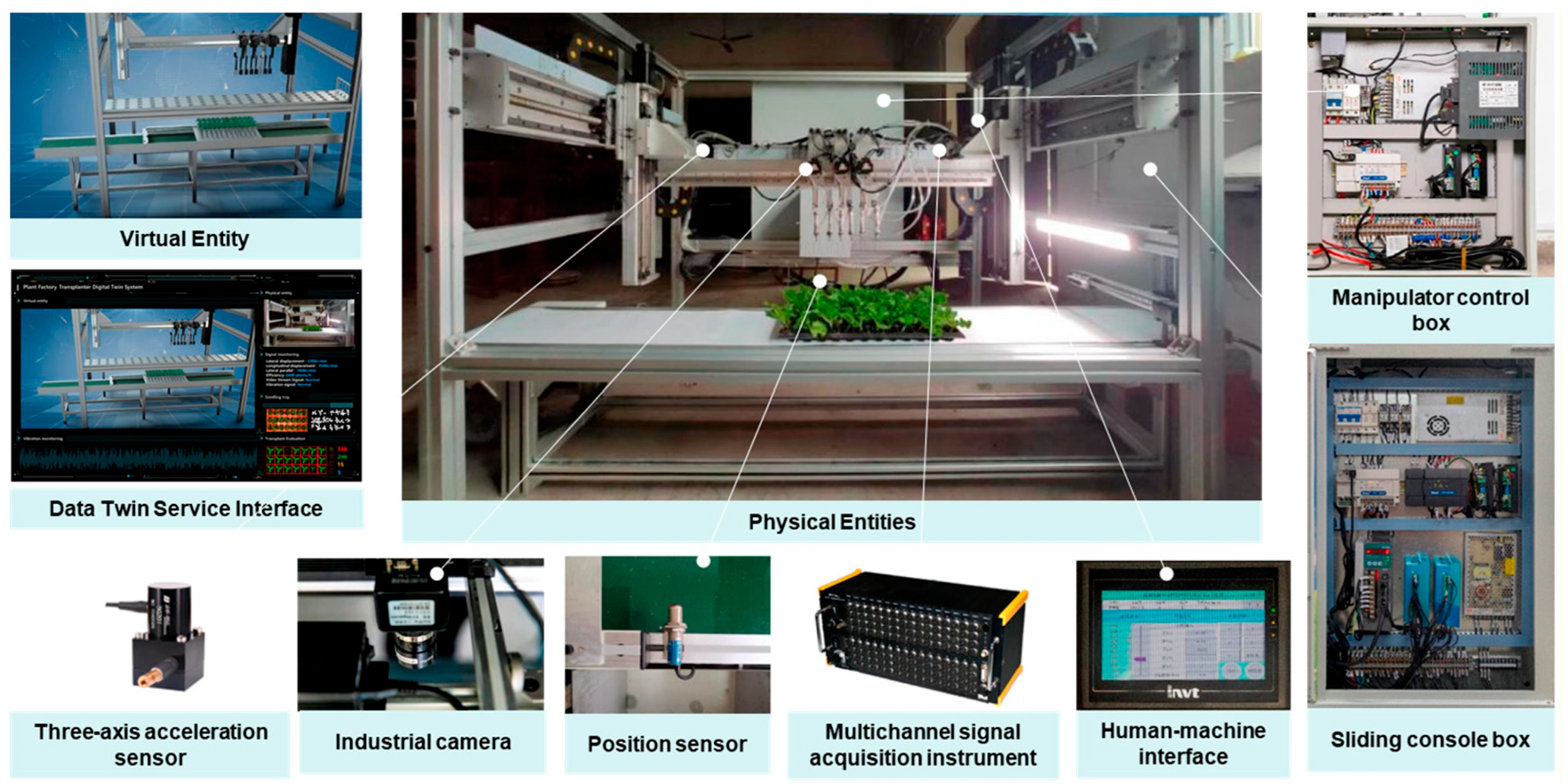

- Chen, K.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Niu, K.; Jin, X.; Xu, B.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, Y. Digital Twin-Based Vibration Monitoring of Plant Factory Transplanting Machine. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiao, J.; Tian, Y.; Ma, S.; Liu, H.; Huang, T. Chatter-free and high-quality end milling for thin-walled workpieces through a follow-up support technology. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 312, 117857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bai, Q.; Cheng, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ding, H. Investigation on an in-process chatter detection strategy for micro-milling titanium alloy thin-walled parts and its implementation perspectives. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 183, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zou, B.; Chen, W.; Xue, K.; Huang, C. Chatter failure comparison for high-speed milling of aerospace GH4099 with silicon nitride ceramic end mills: A laboratory scale investigation. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 157, 107891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Wang, P.; Cheng, K.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y. Machining dynamics and chatters in micro-milling: A critical review on the state-of-the-art and future perspectives. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model Type | Principle | Parameter Source | Applicability Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical/analytical models | Empirical formulas | Small number of experiments | Process design, online rough prediction |

| Mechanistic Models | Mechanics of shear zone, friction zone | Calibration tests | Process analysis, optimization |

| Finite-Element Models | Numerical solution of governing equations | Fine mesh and model | Offline research, mechanism verification |

| ML | Learning mapping relations from data | Large experimental datasets | Online monitoring, prediction for specific systems |

| Planning Strategy | Primary Optimization Objective | Algorithm Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric shortest path | Reduce non-cutting travel time | Low |

| Constant material removal rate | Maintain stable cutting load | Medium |

| Dynamics-constrained optimization | Avoid chatter, smooth motion | High |

| Application Objectives | Mathematical Methods Involved | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Geometric description and interpolation | Computational geometry | Parametric curves/surfaces (NURBS, Bézier) describe tool paths, isometric curves generate circular cutting paths, etc. |

| Path smoothing | Differential geometry (B-spline curve, least square fitting, etc.) | Curvature calculation guidance point encryption (high curvature area), normal vector control tool attitude, Gaussian spherical mapping optimization tool-axis vector |

| Global path optimization | Numerical calculation | Particle swarm optimization (PSO) for curvature optimization and simulated annealing for NURBS control point weight optimization |

| Segmentation and optimization of processing area | Optimization algorithm, normal vector calculation | Geometric division of point cloud region |

| Accuracy compensation Tool location and tool-axis planning | Numerical calculation and interpolation/coordinate transformation, spherical mapping | Spline interpolation smoothing sensor signal, adaptive iterative adjustment of interpolation points, etc. |

| Dynamic path planning | Deepening learning and other ML | - |

| Suppression Strategy | Operating Principle | Implementation Stage |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter optimization | Operate outside unstable lobes in stability diagram | Process planning |

| Variable spindle speed | Disrupt regenerative chatter period | Online |

| Passive dampers | Add mass/damping to absorb energy | Machine design/retrofitting |

| Active control | Apply counter-phase control force to cancel vibration | Online, real-time |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jiang, Q.; Song, J. A Review on Cutting Force and Thermal Modeling, Toolpath Planning, and Vibration Suppression for Advanced Manufacturing. Machines 2026, 14, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010060

Jiang Q, Song J. A Review on Cutting Force and Thermal Modeling, Toolpath Planning, and Vibration Suppression for Advanced Manufacturing. Machines. 2026; 14(1):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010060

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Qingyang, and Juan Song. 2026. "A Review on Cutting Force and Thermal Modeling, Toolpath Planning, and Vibration Suppression for Advanced Manufacturing" Machines 14, no. 1: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010060

APA StyleJiang, Q., & Song, J. (2026). A Review on Cutting Force and Thermal Modeling, Toolpath Planning, and Vibration Suppression for Advanced Manufacturing. Machines, 14(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines14010060